0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

110 viewsPeople Vs Libnao 2003

People Vs Libnao 2003

Uploaded by

Zan BillonesThis document summarizes a Supreme Court of the Philippines case. Two women, Agpanga Libnao and Rosita Nunga, were arrested after police found eight kilos of marijuana in a bag on their tricycle. At trial, they were convicted of drug trafficking. Libnao appealed, arguing her arrest and the search were unlawful. The Supreme Court upheld the conviction, finding the warrantless search of the moving vehicle was valid due to impracticability of obtaining a warrant. It ruled the police had probable cause to believe the vehicle contained illegal drugs.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

People Vs Libnao 2003

People Vs Libnao 2003

Uploaded by

Zan Billones0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

110 views5 pagesThis document summarizes a Supreme Court of the Philippines case. Two women, Agpanga Libnao and Rosita Nunga, were arrested after police found eight kilos of marijuana in a bag on their tricycle. At trial, they were convicted of drug trafficking. Libnao appealed, arguing her arrest and the search were unlawful. The Supreme Court upheld the conviction, finding the warrantless search of the moving vehicle was valid due to impracticability of obtaining a warrant. It ruled the police had probable cause to believe the vehicle contained illegal drugs.

Original Description:

asdf

Original Title

People vs Libnao 2003

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

This document summarizes a Supreme Court of the Philippines case. Two women, Agpanga Libnao and Rosita Nunga, were arrested after police found eight kilos of marijuana in a bag on their tricycle. At trial, they were convicted of drug trafficking. Libnao appealed, arguing her arrest and the search were unlawful. The Supreme Court upheld the conviction, finding the warrantless search of the moving vehicle was valid due to impracticability of obtaining a warrant. It ruled the police had probable cause to believe the vehicle contained illegal drugs.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

110 views5 pagesPeople Vs Libnao 2003

People Vs Libnao 2003

Uploaded by

Zan BillonesThis document summarizes a Supreme Court of the Philippines case. Two women, Agpanga Libnao and Rosita Nunga, were arrested after police found eight kilos of marijuana in a bag on their tricycle. At trial, they were convicted of drug trafficking. Libnao appealed, arguing her arrest and the search were unlawful. The Supreme Court upheld the conviction, finding the warrantless search of the moving vehicle was valid due to impracticability of obtaining a warrant. It ruled the police had probable cause to believe the vehicle contained illegal drugs.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 5

1

Republic of the Philippines

SUPREME COURT

Manila

THIRD DIVISION

G.R. No. 136860 January 20, 2003

PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, plaintiff-appellee,

vs.

AGPANGA LIBNAO y KITTEN and ROSITA NUNGA y VALENCIA,

accused.

AGPANGA LIBNAO y KITTEN, accused-appellant.

PUNO, J .:

Before us is an appeal from the Decision dated November 19, 1998 of the

Regional Trial Court, Branch 65, Tarlac City, finding appellant Agpanga

Libnao and her co-accused Rosita Nunga guilty of violating Article II, Section

4 of R.A. No. 6425, otherwise known as the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1972.

1

For their conviction, each was sentenced to suffer an imprisonment of

reclusion perpetua and to pay a fine of two million pesos.

Appellant and her co-accused were charged under the following Information:

"That on or about October 20, 1996 at around 1:00 oclock dawn, in

the Municipality of Tarlac, Province of Tarlac, Philippines, and within

the jurisdiction of this Honorable Court, the above-named accused

conspiring, confederating and helping with one another, without

being lawfully authorized, did then and there willfully, unlawfully and

feloniously make delivery/transport with intent to sell marijuana

leaves wrapped in a transparent plastic weighing approximately

eight (8) kilos, which is in violation of Section 4, Article II of RA 6425,

otherwise known as the Dangerous Drugs Act of 1972, as amended.

CONTRARY TO LAW."

2

During their arraignment, both entered a plea of Not Guilty. Trial on the

merits ensued.

It appears from the evidence adduced by the prosecution that in August of

1996, intelligence operatives of the Philippine National Police (PNP)

stationed in Tarlac, Tarlac began conducting surveillance operation on

suspected drug dealers in the area. They learned from their asset that a

certain woman from Tajiri, Tarlac and a companion from Baguio City were

transporting illegal drugs once a month in big bulks.

On October 19, 1996, at about 10 oclock in the evening, Chief Inspector

Benjamin Arceo, Tarlac Police Chief, held a briefing in connection with a tip

which his office received that the two drug pushers, riding in a tricycle, would

be making a delivery that night. An hour later, the Police Alert Team installed

a checkpoint in Barangay Salapungan to apprehend the suspects. Witness

SPO1 Marlon Gamotea, PO3 Florante Ferrer and SPO3 Roberto Aquino

were assigned to man the checkpoint.

At about 1:00 oclock in the morning of the following day, SPO1 Gamotea

and PO3 Ferrer flagged down a passing tricycle. It had two female

passengers seated inside, who were later identified as the appellant

Agpanga Libnao and her co-accused Rosita Nunga.

3

In front of them was a

black bag. Suspicious of the black bag and the twos uneasy behavior when

asked about its ownership and content, the officers invited them to Kabayan

Center No.2 located at the same barangay. They brought with them the

black bag.

Upon reaching the center, PO3 Ferrer fetched Barangay Captain Roy

Pascual to witness the opening of the black bag. In the meantime, the two

women and the bag were turned over to the investigator on duty, SPO3

Arthur Antonio. As soon as the barangay captain arrived, the black bag was

opened in the presence of the appellant, her co-accused and personnel of

the center. Found inside it were eight bricks of leaves sealed in plastic bags

and covered with newspaper. The leaves were suspected to be marijuana.

To determine who owns the bag and its contents, SPO3 Antonio

interrogated the two. Rosita Nunga stated that it was owned by the

appellant. The latter, in turn, disputed this allegation. Thereafter, they were

made to sign a confiscation receipt without the assistance of any counsel, as

they were not informed of their right to have one. During the course of the

investigation, not even close relatives of theirs were present.

The seized articles were later brought to the PNP Crime Laboratory in San

Fernando, Pampanga on October 23, 1996. Forensic Chemist Daisy P.

2

Babu conducted a laboratory examination on them. She concluded that the

articles were marijuana leaves weighing eight kilos.

4

For their part, both accused denied the accusation against them. Rosita

Nunga testified that in the evening of October 19,1996, she went to buy

medicine for her ailing child at a pharmacy near the Tarlac Provincial

Hospital. The child was suffering from diarrhea, occasioned by abdominal

pain. To return to their house, she boarded a tricycle bound for Barangay

Tariji, where she resides. Along the way, the tricycle she was riding was

flagged down by a policeman at a checkpoint in Barangay Salapungan. She

was taken aback when the officer invited her to the Kabayan Center. It was

there that she was confronted with the black bag allegedly containing eight

bricks of marijuana leaves. She disputed owning the bag and knowing its

contents. She also denied sitting beside the appellant in the passengers

seat inside the tricycle, although she admitted noticing a male passenger

behind the driver.

Remarkably, appellant did not appear in court and was only represented by

her lawyer. The latter marked and submitted in evidence an affidavit

executed by one Efren Gannod, a security guard of Philippine Rabbit Bus

Lines in Tarlac, Tarlac. The sworn statement declared that at about 0220H

on October 20, 1996, SPO2 Antonio arrived at their terminal and arrested a

certain woman who boarded their Bus No. 983. The incident was recorded in

the companys logbook. Gannod, however, was not presented in court to

attest that the woman referred in his affidavit was the appellant.

After trial, the court convicted appellant and her co-accused Rosita Nunga,

thus:

"WHEREFORE, finding both accused guilty beyond reasonable

doubt of the offense of violation of Article II, Section 4 of RA 6425 in

relation to RA 7659, they are hereby sentenced to suffer an

imprisonment of reclusion perpetua and to pay a fine of two million

pesos.

SO ORDERED."

5

Aggrieved by the verdict, appellant interposed the present appeal. In her

brief, she assigned the following errors:

"1. The Honorable Regional Trial Court failed to appreciate the

contention of the defense that the right of accused against illegal

and unwarranted arrest and search was violated by the police

officers who arrested both accused.

2. The Honorable Court failed to appreciate the contention of the

defense that the right of the accused to custodial investigation was

deliberately violated by the peace officers who apprehended and

investigated the accused.

3. The Honorable Court miserably failed to evaluate the material

inconsistencies in the testimonies of the prosecutions witnesses

which inconsistencies cast doubt and make incredible the contention

and version of the prosecution.

4. The Honorable Court gravely abused its discretion when it

appreciated and considered the documentary and object evidence of

the prosecution not formally offered amounting to ignorance of the

law."

6

We are not persuaded by these contentions; hence, the appeal must be

dismissed.

In arguing that her arrest was unlawful, appellant capitalizes on the absence

of a warrant for her arrest. She contends that at the time she was

apprehended by the police officers, she was not committing any offense but

was merely riding a tricycle. In the same manner, she impugns the search

made on her belongings as illegal as it was done without a valid warrant or

under circumstances when warrantless search is permissible. Consequently,

any evidence obtained therein is inadmissible against her.

These arguments fail to impress. The general rule is that a search may be

conducted by law enforcers only on the strength of a search warrant validly

issued by a judge as provided in Article III, Section 2 of the 1987

Constitution, thus:

"The right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses,

papers and effects against unreasonable searches and seizures of

whatever nature and for any purpose shall be inviolable, and no

search warrant and warrant of arrest shall issue except upon

probable cause to be determined personally by the judge after

examination under oath or affirmation of the complainant and the

witnesses he may produce, and particularly describing the place to

be searched and the persons or things to be seized."

7

3

The constitutional guarantee is not a blanket prohibition against all searches

and seizures as it operates only against "unreasonable" searches and

seizures. Searches and seizures are as a rule unreasonable unless

authorized by a validly issued search warrant or warrant of arrest. Thus, the

fundamental protection accorded by the search and seizure clause is that

between persons and police must stand the protective authority of a

magistrate clothed with power to issue or refuse to issue search warrants

and warrants of arrest.

8

Be that as it may, the requirement that a judicial warrant must be obtained

prior to the carrying out of a search and seizure is not absolute. There are

certain familiar exceptions to the rule, one of which relates to search of

moving vehicles.

9

Warrantless search and seizure of moving vehicles are

allowed in recognition of the impracticability of securing a warrant under said

circumstances as the vehicle can be quickly moved out of the locality or

jurisdiction in which the warrant may be sought.

10

Peace officers in such

cases, however, are limited to routine checks where the examination of the

vehicle is limited to visual inspection.

11

When a vehicle is stopped and

subjected to an extensive search, such would be constitutionally permissible

only if the officers made it upon probable cause, i.e., upon a belief,

reasonably arising out of circumstances known to the seizing officer, that an

automobile or other vehicle contains as item, article or object which by law is

subject to seizure and destruction.

12

In earlier decisions, we held that there was probable cause in the following

instances: (a) where the distinctive odor of marijuana emanated from the

plastic bag carried by the accused;

13

(b) where an informer positively

identified the accused who was observed to be acting suspiciously;

14

(c)

where the accused who were riding a jeepney were stopped and searched

by policemen who had earlier received confidential reports that said accused

would transport a quantity of marijuana;

15

(d) where Narcom agents had

received information that a Caucasian coming from Sagada, Mountain

Province had in his possession prohibited drugs and when the Narcom

agents confronted the accused Caucasian because of a conspicuous bulge

in his waistline, he failed to present his passport and other identification

papers when requested to do so;

16

(f) where the moving vehicle was stopped

and searched on the basis of intelligence information and clandestine

reports by a deep penetration agent or spy -- one who participated in the

drug smuggling activities of the syndicate to which the accused belong --

that said accused were bringing prohibited drugs into the country;

17

(g)

where the arresting officers had received a confidential information that the

accused, whose identity as a drug distributor was established in a previous

test-buy operation, would be boarding MV Dona Virginia and probably

carrying shabu with him;

18

(h) where police officers received an information

that the accused, who was carrying a suspicious-looking gray luggage bag,

would transport marijuana in a bag to Manila;

19

and (i) where the

appearance of the accused and the color of the bag he was carrying fitted

the description given by a civilian asset.

20

The warrantless search in the case at bench is not bereft of a probable

cause. The Tarlac Police Intelligence Division had been conducting

surveillance operation for three months in the area. The surveillance yielded

the information that once a month, appellant and her co-accused Rosita

Nunga transport drugs in big bulks. At 10:00 pm of October 19, 1996, the

police received a tip that the two will be transporting drugs that night riding a

tricycle. Surely, the two were intercepted three hours later, riding a tricycle

and carrying a suspicious-looking black bag, which possibly contained the

drugs in bulk. When they were asked who owned it and what its content

was, both became uneasy. Under these circumstances, the warrantless

search and seizure of appellants bag was not illegal.

It is also clear that at the time she was apprehended, she was committing a

criminal offense. She was making a delivery or transporting prohibited drugs

in violation of Article II, Section 4 of R.A. No. 6425. Under the Rules of

Court, one of the instances a police officer is permitted to carry out a

warrantless arrest is when the person to be arrested is caught committing a

crime in flagrante delicto, thus:

"Section 5. Arrest without Warrant; when lawful. - A peace officer or

a private person may, without warrant, arrest a person:

(a) When in his presence, the person to be arrested has

committed, is actually committing, or is attempting to commit an

offense;

(b) When an offense has in fact just been committed, and he has

probable cause to believe based on personal knowledge of facts or

circumstances that the person to be arrested has committed it; and

(c) When the person to be arrested is a prisoner who has escaped

from a penal establishment or place where he is serving final

judgment or temporarily confined while his case is pending, or has

escaped while being transferred from one confinement to another.

x x x."

21

(emphasis supplied)

4

Appellant also takes issue of the fact that she was not assisted by a lawyer

when police officers interrogated her. She claimed that she was not duly

informed of her right to remain silent and to have competent counsel of her

choice. Hence, she argues that the confession or admission obtained therein

should be considered inadmissible in evidence against her.

These contentions deserve scant attention. Appellant did not make any

confession during her custodial investigation. In determining the guilt of the

appellant and her co-accused, the trial court based its decision on the

testimonies of prosecution witnesses and on the existence of the confiscated

marijuana. We quote the relevant portion of its decision:

"Earlier in the course of the proceedings, the court then presided by

Judge Angel Parazo, granted bail to accused Agpanga Libnao,

ruling that the confiscation receipt signed by both accused (Exhibit

"C") is inadmissible because they were not assisted by a counsel.

Confronted with this same issue, this court finds the postulate to rest

on good authority and will therefore reiterate its inadmissibility.

Since the prosecution had not presented any extrajudicial

confession extracted from both accused as evidence of their guilt,

the court finds it needless to discuss any answer given by both

accused as a result of the police interrogation while in their custody.

By force of necessity, therefore, the only issue to be resolved

by the court is whether or not, based on the prosecutions

evidence, both accused can be convicted."

22

(emphasis supplied)

Appellant then faults the trial court for appreciating and taking into account

the object and documentary evidence of the prosecution despite the latters

failure to formally offer them. Absent any formal offer, she argues that they

again must be deemed inadmissible.

The contention is untenable. Evidence not formally offered can be

considered by the court as long as they have been properly identified by

testimony duly recorded and they have themselves been incorporated in the

records of the case.

23

All the documentary and object evidence in this case

were properly identified, presented and marked as exhibits in court, including

the bricks of marijuana.

24

Even without their formal offer, therefore, the

prosecution can still establish the case because witnesses properly identified

those exhibits, and their testimonies are recorded.

25

Furthermore, appellants

counsel had cross-examined the prosecution witnesses who testified on the

exhibits.

26

Appellant also assails the credibility of the testimonies of the prosecution

witnesses. She first cites the inconsistency between the testimony of SPO1

Marlon Gamotea, who said that it was SPO2 Antonio who opened the black

bag containing the marijuana; and that of SPO2 Antonio, who declared that

the bag was already open when he arrived at the Kabayan Center. She then

focuses on the police officers failure to remember the family name of the

driver of the tricycle where she allegedly rode, claiming that this is

improbable and contrary to human experience.

Again, appellants arguments lack merit. The alleged inconsistencies she

mentions refer only to minor details and not to material points regarding the

basic elements of the crime. They are inconsequential that they do not affect

the credibility of the witnesses nor detract from the established fact that

appellant and her co-accused were transporting marijuana. Testimonies of

witnesses need only corroborate each other on important and relevant

details concerning the principal occurrence.

27

The identity of the person who

opened the bag is clearly immaterial to the guilt of the appellant. Besides, it

is to be expected that the testimony of witnesses regarding the same

incident may be inconsistent in some aspects because different persons

may have different recollections of the same incident.

28

Likewise, we find nothing improbable in the failure of the police officers to

note and remember the name of the tricycle driver for the reason that it was

unnecessary for them to do so. It was not shown that the driver was in

complicity with the appellant and her co-accused in the commission of the

crime.

To be sure, credence was properly accorded to the testimonies of

prosecution witnesses, who are law enforcers. When police officers have no

motive to testify falsely against the accused, courts are inclined to uphold

this presumption.

29

In this case, no evidence has been presented to suggest

any improper motive on the part of the police enforcers in arresting the

appellant.

Against the credible positive testimonies of the prosecution witnesses,

appellants defense of denial and alibi cannot stand. The defense of denial

and alibi has been invariably viewed by the courts with disfavor for it can just

as easily be concocted and is a common and standard defense ploy in most

cases involving violation of the Dangerous Drugs Act.

30

It has to be

substantiated by clear and convincing evidence.

31

The sole proof presented

in the lower court by the appellant to support her claim of denial and alibi

5

was a sworn statement, which was not even affirmed on the witness stand

by the affiant. Hence, we reject her defense.

IN VIEW WHEREOF, the instant appeal is DENIED. The decision of the trial

court finding appellant guilty beyond reasonable doubt of the offense of

violation of Article II, Section 4 of R.A. No. 6425 in relation to R.A. No. 7659,

and sentencing her to an imprisonment of reclusion perpetua and to pay a

fine of two million pesos is hereby AFFIRMED.

SO ORDERED.

You might also like

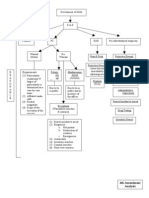

- 4th Amendment Flow ChartDocument1 page4th Amendment Flow ChartJackie RobertsNo ratings yet

- Community PolicingDocument45 pagesCommunity PolicingMokhtar Abdullah67% (6)

- People vs. Libnao (GR 136860, 20 January 2003)Document3 pagesPeople vs. Libnao (GR 136860, 20 January 2003)Ei BinNo ratings yet

- Demurrer To Evidence - Ron Oliver ReyesDocument20 pagesDemurrer To Evidence - Ron Oliver ReyesNK Mndza100% (1)

- Booking Report 3-31-2021Document3 pagesBooking Report 3-31-2021WCTV Digital TeamNo ratings yet

- Check PointDocument31 pagesCheck PointDennis TolentinoNo ratings yet

- People v. LibnaoDocument5 pagesPeople v. LibnaoMoireeGNo ratings yet

- Vs. ROSA ARUTA y MENGUIN, Accused-AppellantDocument15 pagesVs. ROSA ARUTA y MENGUIN, Accused-AppellantJof BotorNo ratings yet

- PP vs. Bronola - EJ ConfessionDocument11 pagesPP vs. Bronola - EJ ConfessionhlcameroNo ratings yet

- People Vs Fbronola (FT)Document11 pagesPeople Vs Fbronola (FT)Lemuel Lagasca Razalan IVNo ratings yet

- Case 11 G.R. No. 213225Document10 pagesCase 11 G.R. No. 213225Love UmpaNo ratings yet

- Warrantless Arrest and Search - "Peeping" VsDocument17 pagesWarrantless Arrest and Search - "Peeping" VsShaNe BesaresNo ratings yet

- People Vs FbronolaDocument18 pagesPeople Vs FbronolaGladys Laureta GarciaNo ratings yet

- PP Vs Aruta, 288 Scra 626 G.R. No. 120915 April 3, 1998Document13 pagesPP Vs Aruta, 288 Scra 626 G.R. No. 120915 April 3, 1998Ronald Alasa-as AtigNo ratings yet

- Third Division G.R. No. 120915. April 3, 1998 THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, Decision Romero, J.Document38 pagesThird Division G.R. No. 120915. April 3, 1998 THE PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, Decision Romero, J.Leeanji GalamgamNo ratings yet

- Philippine Jurispridence 34Document9 pagesPhilippine Jurispridence 34al gulNo ratings yet

- People vs. ArutaDocument17 pagesPeople vs. ArutaGeanelleRicanorEsperonNo ratings yet

- People v. ArutaDocument12 pagesPeople v. ArutaTrixie MarianoNo ratings yet

- People Vs Aruta PDFDocument15 pagesPeople Vs Aruta PDFChristian John Dela CruzNo ratings yet

- People v. Aruta - CaseDocument16 pagesPeople v. Aruta - CaseRobeh AtudNo ratings yet

- Constitutional Law - Searches and Seizures DigestsDocument11 pagesConstitutional Law - Searches and Seizures DigestsSharmaine Alisa BasinangNo ratings yet

- Al.," Affirming The Trial Court's Verdict of Conviction Against Appellants Corazon Nazareno y FernandezDocument8 pagesAl.," Affirming The Trial Court's Verdict of Conviction Against Appellants Corazon Nazareno y FernandezRuby Anna TorresNo ratings yet

- People VSDocument2 pagesPeople VSKaiiSophieNo ratings yet

- Chapter IV Consti Law II p2Document9 pagesChapter IV Consti Law II p2dragon knightNo ratings yet

- People v. Aruta (Incidental To Lawful Arrest)Document5 pagesPeople v. Aruta (Incidental To Lawful Arrest)kjhenyo218502No ratings yet

- Draft Decision (Final Paper)Document10 pagesDraft Decision (Final Paper)JeffersonLegadoNo ratings yet

- 143-212 Consti2 TineDocument21 pages143-212 Consti2 Tinefadzram joefox100% (1)

- People v. CompradoDocument3 pagesPeople v. CompradoElla B.67% (3)

- Sec. 6 - Issuance and Form of Search Warrant People of The Philippines, Plaintiff-Appellee vs. Olive Rubio Mamaril, Accused-AppellantDocument5 pagesSec. 6 - Issuance and Form of Search Warrant People of The Philippines, Plaintiff-Appellee vs. Olive Rubio Mamaril, Accused-AppellantKGTorresNo ratings yet

- Minda Clemente vs. PeopleDocument3 pagesMinda Clemente vs. PeopleFrancess PiloneoNo ratings yet

- Pp. vs. Aruta PDFDocument9 pagesPp. vs. Aruta PDFJerome MoradaNo ratings yet

- Nelson Valleno y Lucito VsDocument4 pagesNelson Valleno y Lucito Vs楊瑪莉No ratings yet

- People vs. BagistaDocument7 pagesPeople vs. BagistaJohn Ludwig Bardoquillo PormentoNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 91107Document10 pagesG.R. No. 91107Abbas AskariNo ratings yet

- January To December 2013 Case DigestDocument154 pagesJanuary To December 2013 Case DigestNoel Cagigas Felongco100% (3)

- People vs. FBRONOLADocument13 pagesPeople vs. FBRONOLAMADEE VILLANUEVANo ratings yet

- Crimproc CasesDocument35 pagesCrimproc CasesSharina Wee JayagNo ratings yet

- People of The Philippines vs. Mallari CaseDocument66 pagesPeople of The Philippines vs. Mallari CaseEugene DayanNo ratings yet

- Lawphil Net Judjuris Juri2010 Oct2010 GR 190179 2010 HTMLDocument1 pageLawphil Net Judjuris Juri2010 Oct2010 GR 190179 2010 HTMLDenison CordovaNo ratings yet

- Searches and SeizuresDocument6 pagesSearches and Seizuresbrigette100% (2)

- 05 G.R. No. 86218 People v. Bagista-ExpandedDocument8 pages05 G.R. No. 86218 People v. Bagista-ExpandedIvy Beronilla LubianoNo ratings yet

- Proof Beyond Reasonable DoubtDocument6 pagesProof Beyond Reasonable DoubtDeen MerkaNo ratings yet

- Equal Protection ClauseDocument6 pagesEqual Protection ClauseThea Faye Buncad CahuyaNo ratings yet

- Evidence Outline 2022Document15 pagesEvidence Outline 2022Ricca ResulaNo ratings yet

- People Vs GesmundoDocument5 pagesPeople Vs GesmundoJomar TenezaNo ratings yet

- Compilation of 2014 Drug CasesDocument340 pagesCompilation of 2014 Drug CasesChingkay Valente - JimenezNo ratings yet

- Facts: in An Information Filed Against The Accused-Appellant Mikael Malmstead WasDocument4 pagesFacts: in An Information Filed Against The Accused-Appellant Mikael Malmstead Wasmelaniem_1No ratings yet

- Constitution Statutes Executive Issuances Judicial Issuances Other Issuances Jurisprudence International Legal Resources AUSL ExclusiveDocument7 pagesConstitution Statutes Executive Issuances Judicial Issuances Other Issuances Jurisprudence International Legal Resources AUSL ExclusiveShannon Gail MaongsongNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court Decisions: Political LawDocument15 pagesSupreme Court Decisions: Political LawBetchie CrisostomoNo ratings yet

- People vs. LibnaoDocument10 pagesPeople vs. LibnaoKate DomingoNo ratings yet

- Consti CompilationDocument209 pagesConsti CompilationMariaAyraCelinaBatacanNo ratings yet

- Crim Pro Full Cases Part 1Document121 pagesCrim Pro Full Cases Part 1mlucagbo80773No ratings yet

- People vs. BagistaDocument6 pagesPeople vs. BagistaWilma P.No ratings yet

- People vs. RachoDocument6 pagesPeople vs. RachoMay Frances Calsiyao100% (1)

- 4.) People V ManansalaDocument9 pages4.) People V ManansalaMaya Angelique JajallaNo ratings yet

- Full CaseDocument9 pagesFull CaseOmie Jehan Hadji-AzisNo ratings yet

- People v. Nazareno_Document8 pagesPeople v. Nazareno_rvci2016No ratings yet

- Manalili Vs CADocument6 pagesManalili Vs CALibay Villamor IsmaelNo ratings yet

- Valdez V People GR170180Document10 pagesValdez V People GR170180Jesus Angelo DiosanaNo ratings yet

- PEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. JERRY Sapla Y Guerrero A.K.A. Eric Salibad Y Mallari, AccusedDocument39 pagesPEOPLE OF THE PHILIPPINES, Plaintiff-Appellee, vs. JERRY Sapla Y Guerrero A.K.A. Eric Salibad Y Mallari, AccusedNadzlah BandilaNo ratings yet

- People v. TuazonDocument7 pagesPeople v. TuazonIan TaduranNo ratings yet

- Case DigestDocument8 pagesCase DigestMV FadsNo ratings yet

- 1 Cebu Portland Cement V CTADocument3 pages1 Cebu Portland Cement V CTAZan BillonesNo ratings yet

- Crime Elements Penalty Notes: Art. 262. Mutilation Intent Is To Specifically To CastrateDocument6 pagesCrime Elements Penalty Notes: Art. 262. Mutilation Intent Is To Specifically To CastrateZan BillonesNo ratings yet

- Be It Enacted by The Senate and The House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledDocument8 pagesBe It Enacted by The Senate and The House of Representatives of The Philippines in Congress AssembledZan BillonesNo ratings yet

- Arellano Outline Land ClassificationDocument6 pagesArellano Outline Land ClassificationZan BillonesNo ratings yet

- 2-2 Cruzvale V LaguesmaDocument3 pages2-2 Cruzvale V LaguesmaZan BillonesNo ratings yet

- Art. 262. Mutilation: Crime Elements Penalty NotesDocument6 pagesArt. 262. Mutilation: Crime Elements Penalty NotesZan BillonesNo ratings yet

- 08 Mustang Lumber V CA (1996)Document7 pages08 Mustang Lumber V CA (1996)Zan BillonesNo ratings yet

- 2-1 Algire V de MesaDocument3 pages2-1 Algire V de MesaZan Billones100% (1)

- 09 Ramos V Director of Lands (1918)Document4 pages09 Ramos V Director of Lands (1918)Zan BillonesNo ratings yet

- 09 Ramos V Director of Lands (1918)Document5 pages09 Ramos V Director of Lands (1918)Zan BillonesNo ratings yet

- 419-427 Serious Misconduct 282 (A)Document8 pages419-427 Serious Misconduct 282 (A)Zan BillonesNo ratings yet

- 440-446 Gross and Habitual Neglect of DutiesDocument8 pages440-446 Gross and Habitual Neglect of DutiesZan BillonesNo ratings yet

- Section 1: Article Xii National Economy and PatrimonyDocument5 pagesSection 1: Article Xii National Economy and PatrimonyZan BillonesNo ratings yet

- 10 Ankron V Govt of Phil Islands (1919)Document2 pages10 Ankron V Govt of Phil Islands (1919)Zan BillonesNo ratings yet

- 447-454 Abandonment of WorkDocument5 pages447-454 Abandonment of WorkZan BillonesNo ratings yet

- Diamond Motors V Court of Appeals 417 SCRA 46 (2003) Just Causes - Fraud FactsDocument3 pagesDiamond Motors V Court of Appeals 417 SCRA 46 (2003) Just Causes - Fraud FactsZan BillonesNo ratings yet

- 433 439 InsubordinationDocument7 pages433 439 InsubordinationZan BillonesNo ratings yet

- 03 People v. Sesbreno (1999)Document11 pages03 People v. Sesbreno (1999)Zan BillonesNo ratings yet

- People Vs Dela Cruz DigestDocument2 pagesPeople Vs Dela Cruz Digestangelsu04100% (1)

- Incident Record Form: Philippine National PoliceDocument3 pagesIncident Record Form: Philippine National PoliceBeca May PidlaoNo ratings yet

- Journalists Exposing Corruption Could Face Prosecution Say West Yorkshire PoliceDocument4 pagesJournalists Exposing Corruption Could Face Prosecution Say West Yorkshire PolicePoliceCorruptionNo ratings yet

- Case 14 G.R. No. 170672Document6 pagesCase 14 G.R. No. 170672Love UmpaNo ratings yet

- 2021 Labette County Community Guide - 64Document1 page2021 Labette County Community Guide - 64PKjournalistNo ratings yet

- Somali Police Force Trained in Community Policing To Counter ExtremismDocument4 pagesSomali Police Force Trained in Community Policing To Counter ExtremismAMISOM Public Information ServicesNo ratings yet

- Case 11 and 15 DigestDocument7 pagesCase 11 and 15 DigestMercy LingatingNo ratings yet

- Compiled Case Digest For Searches and Seizure and ArrestDocument68 pagesCompiled Case Digest For Searches and Seizure and Arrestcristine jagodillaNo ratings yet

- PowerPoint For Biannual Community Safety ReportDocument15 pagesPowerPoint For Biannual Community Safety ReportSarah McRitchieNo ratings yet

- Module 1: An Introduction To The Investigation Procedure: 1.1 Cognizable and Non-Cognizable OffencesDocument3 pagesModule 1: An Introduction To The Investigation Procedure: 1.1 Cognizable and Non-Cognizable OffencesAngela JohnNo ratings yet

- People vs. SayconDocument3 pagesPeople vs. SayconMaria Cherrylen Castor QuijadaNo ratings yet

- Rights of Suspects 1-5Document5 pagesRights of Suspects 1-5Denise Michaela YapNo ratings yet

- Position Paper:Memorandum - Sample - Academic PuporseDocument19 pagesPosition Paper:Memorandum - Sample - Academic PuporsethebeautyinsideNo ratings yet

- Corpus Juris SL 1Document8 pagesCorpus Juris SL 1Haris PalpolaNo ratings yet

- Plaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Grajo T. Albano and Teresita Dizon CapulongDocument8 pagesPlaintiff-Appellee Vs Vs Accused-Appellant The Solicitor General Grajo T. Albano and Teresita Dizon CapulongChristian VillarNo ratings yet

- YONKERS, NY - July 1, 2013 - Yonkers Mayor Mike Spano Along With The Yonkers PoliceDocument2 pagesYONKERS, NY - July 1, 2013 - Yonkers Mayor Mike Spano Along With The Yonkers PoliceColin GustafsonNo ratings yet

- People Vs FbronolaDocument18 pagesPeople Vs FbronolaGladys Laureta GarciaNo ratings yet

- List of Criminology Thesis PDFDocument5 pagesList of Criminology Thesis PDFMichael V ValienteNo ratings yet

- List of 2010-2011 CriminologyDocument4 pagesList of 2010-2011 CriminologyArman Domingo75% (4)

- InquestDocument5 pagesInquestclandestine2684100% (1)

- Community Safety Education Act Resources 1Document14 pagesCommunity Safety Education Act Resources 1Ben KellerNo ratings yet

- People v. MengoteDocument3 pagesPeople v. MengoteKate QuincoNo ratings yet

- First Information Report (Mamata Naik)Document3 pagesFirst Information Report (Mamata Naik)Åm ÅrNo ratings yet

- Director/ManagerDocument4 pagesDirector/Managerapi-79161329No ratings yet

- Cabañero Vs Cano DigestDocument2 pagesCabañero Vs Cano DigestAlvin Jae MartinNo ratings yet

- Class Notes CRPCDocument61 pagesClass Notes CRPCAjit JaiswalNo ratings yet

- SAN AGUSTIN v. PEOPLEDocument1 pageSAN AGUSTIN v. PEOPLEMichelle Vale CruzNo ratings yet