0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 viewsMss. Came Came

Mss. Came Came

Uploaded by

reacharunkThis document discusses ancient megalithic structures found across different parts of the world, and proposes theories about their origins. It suggests that early Celtic/Druid peoples originated from the same ancestral civilization that built similar stone structures in places as far-flung as India, the Mediterranean, Northern Europe and the British Isles. Colonies from this original group may have migrated and spread megalithic architecture to these distant regions. It also proposes that Phoenician traders from Tyre and Sidon introduced some of these primeval stone structures to Britain.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Mss. Came Came

Mss. Came Came

Uploaded by

reacharunk0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views1 pageThis document discusses ancient megalithic structures found across different parts of the world, and proposes theories about their origins. It suggests that early Celtic/Druid peoples originated from the same ancestral civilization that built similar stone structures in places as far-flung as India, the Mediterranean, Northern Europe and the British Isles. Colonies from this original group may have migrated and spread megalithic architecture to these distant regions. It also proposes that Phoenician traders from Tyre and Sidon introduced some of these primeval stone structures to Britain.

Original Description:

ljlkjljklj

Original Title

EN(27)

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

This document discusses ancient megalithic structures found across different parts of the world, and proposes theories about their origins. It suggests that early Celtic/Druid peoples originated from the same ancestral civilization that built similar stone structures in places as far-flung as India, the Mediterranean, Northern Europe and the British Isles. Colonies from this original group may have migrated and spread megalithic architecture to these distant regions. It also proposes that Phoenician traders from Tyre and Sidon introduced some of these primeval stone structures to Britain.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

16 views1 pageMss. Came Came

Mss. Came Came

Uploaded by

reacharunkThis document discusses ancient megalithic structures found across different parts of the world, and proposes theories about their origins. It suggests that early Celtic/Druid peoples originated from the same ancestral civilization that built similar stone structures in places as far-flung as India, the Mediterranean, Northern Europe and the British Isles. Colonies from this original group may have migrated and spread megalithic architecture to these distant regions. It also proposes that Phoenician traders from Tyre and Sidon introduced some of these primeval stone structures to Britain.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as pdf or txt

You are on page 1of 1

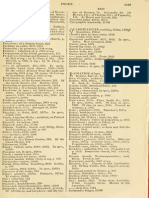

Chap. II.

DRUIDICAL AND CELTIC. 5

tlonn- the forty-fifth parallel of north latitude

;

that, in a similar manner, colonies advanced

from the same great nation hy a southern line through Asia, peopling Syria and Africa, and

arriving at last by sea through the Pillars of Hercules at Britain

;

that the languages of

the western world were the same, and that one system of letters viz. that of the Irish

nniids pervaded the whole, was common to the British Isles and Gaul, to the inhabitants

of Italy, Greece, Syria, Arabia, Persia, and Hindostan

;

and that one of the two alphabets

(of the same system) in which the Irish MSS. are written viz. the Beth-luis-nion came

by Gaul through Britain to Ireland

;

and that the other the Bobeloth came through the

Straits of Gibraltar. Jacob Bryant tliinks that the works called Cyclopean were executed

at a remote age by colonies of some great original nation

;

the only difference between his

ojjinion and tliat of Mr. Higgins being, that the latter calls them Druids, or Celts, from the

time of the dispersion above alluded to.

12. Tlie unliewn stones, whose antiquity and purport is the subject of this section, are

fjiind in Hindostan, where they are denominated

"

jjandoo koolies," and are attributed to a

fabulous being named Pandoo and his sons. With a similarity of character attesting their

common origin, we find them in India, on the shores of the Levant and Mediterranean, in

Belgium, Denmark, Sweden and Norway, in France, and on the shores of Britain from the

Straits of Dover to the Land's End in Cornwall, as well as in many of the interior parts of

the country. They are classed as follows:

1. The Mngle stone, pillar, or obelisk.

2. Circles of stones of ditlerent numoer and arrangement. 3. Sacrificial stones. 4. Crom-

lechs and cairns. 5. Logan stones. G. Tolmen or colossal stones.

13. (1.)

Single Stones. Passanes abjuiid in Scripture in which the practice of erecting

single stones is recorded. The reader on tiiisj point may refer to Gen. xxviii. 18., Jurh/es, ix.

C, 1 Sam vii. 12., 2 Sam. xx. 8., Joshua, xxiv. 27. Tlie single stone might be an emblem

of the generative power of Nature, and thence an object of idolatry. That mentioned in

the first scriptural reference, which Jacob set up in his journey to visit Laban, his uncle, and

wliicli he had used for his pillow, seems, whether from the vision he had while sleeping upon

it, or from some otlier cause, to have become to him an oliject of singular veneration

;

for

lie set it up, and poured oil upon it, and called it" Bethel" (the house of God). It is

curious to observe that some (nllars in Cornwall, assumed to have been erected by the Phoe-

nicians, still retain the api)ellation Bethel. At first, these stones were of no larger dimen-

sion than a man could remove, as in the instance just cited, and that of the Gilgal of

Joshua (/(//. iv.

20.) ; but tiiat which was set up under an oak at Sliechem (ibid. xxiv. 26.),

was a great stone. And here we may notice aiiotlier singular coincitlenee, that of the Botliel

in Cornwall being set up in a place which, from its iiroximiy to an oak which was near the

spot, was called r?othel-ac ; the last syllable being the Saxon for an oak. It appears from

the Scriptures that tliese single stones were raised on various occasions; sometimes, as

in the case of Jacob's Bethel and of Samuel's Ebenezer, to commemorate instances of

divine interposition; sometimes to record a covenant, as in the case of Jacob and Laban

{Gen. xxxi.

48.) ;

sometimes, like the Greek stekc, as sepulchral stones, as in the case of

Rachel's grave (Gen. xxxvi. 20.), 1700 years B.C., according to the usual reckoning. They

were occasionally, also, set up to the memory of individuals, as in the instance of Absalom's

pillar and others. The pillars and altars of the patriarchs appear to have been erected in

honour of the only true God, Jehovah

;

but wherever the Canaanites appeared, they seem

to have been the objects of idolatrous worship, and to have been dedicated to Baal or the

sun, or the other false deities whose altars Moses ordered the Israelites to destroy. The

similarity of pillars of single stones almost at the ojiposite sides of the earth, leaves no doubt

in our mind of their being the work of a people of one common origin widely scattered

;

and the hypotheses of Bryant and Higgins sufficiently account for their appearance in

places so remote from each other. In consequence, says the latter writer, of some cause, no

matter what, the Hive, after the dispersion, casted and sent forth its swarms. One of the

largest descended, according to Genesis (x. 2.),

from Gomer, went north, and then west,

pressed by succeeding swarms, till it arrived at the shores of the Atlantic Ocean, and ulti-

mately colonised Britain. Another branch, observes the same author, proceeded through

Sarmatia southward to the Euxine (Cimmerian Bosphorus)

;

another to Italy, founding

the states of the Umbrii and the Cimmerii, at Cuma, near Naples. Till the time of the

Romans these different lines of march, like so many sheepwalks, were without any walled

cities. Some of the original tribe found their way into Greece, and between the Carpathian

mountains and the Alps into Gaul, scattering a few stragglers as they passed into the

beautiful valleys of the latter, where traces of them in Druidical monuments and language

are occasionally found. Wherever they settled, if the conjecture is correct, they employed

themselves in recovering the lost arts of their ancestors.

14. To the Canaanites of Tyre and Sidon may be chiefly attributed the introduction of

these primeval works into Britain. The Tyrians, inhabiting a sinall slip of barren land,

vrere essentially and necessarily a commercial peojile, and became the most expert and

idvonturous sailors of antiquity. It has been supposed that the constancy of the needle to

the pole,

"

that path which no fowl knoweth, and which the vulture's eye hath not seen."

You might also like

- Timeline BibleDocument5 pagesTimeline BibleJoelHernandezGonzalez100% (15)

- The Golden ThemeDocument13 pagesThe Golden Theme24624No ratings yet

- The Exhaustive Concordance of The BibleDocument1,849 pagesThe Exhaustive Concordance of The Biblepdk5567100% (5)

- Tracing Our Ancestors - Frederick HabermanDocument177 pagesTracing Our Ancestors - Frederick HabermanSaxon Inga100% (5)

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 12, No. 337, October 25, 1828From EverandThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 12, No. 337, October 25, 1828No ratings yet

- Elijah StoryDocument15 pagesElijah StoryKemberly Semaña PentonNo ratings yet

- Counterfeit KJV BiblesDocument5 pagesCounterfeit KJV BiblesNuno NevesNo ratings yet

- Old Testament ParablesDocument5 pagesOld Testament ParablesPescaru DanielNo ratings yet

- Kahlil Gibran Short StoryDocument5 pagesKahlil Gibran Short StorytheresaNo ratings yet

- Liis Is IsDocument1 pageLiis Is IsreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Notes and Queries, Vol. V, Number 119, February 7, 1852 A Medium of Inter-communication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, etc.From EverandNotes and Queries, Vol. V, Number 119, February 7, 1852 A Medium of Inter-communication for Literary Men, Artists, Antiquaries, Genealogists, etc.No ratings yet

- Law6927 4541Document4 pagesLaw6927 4541Shy premierNo ratings yet

- Eco2172 2096Document4 pagesEco2172 2096Muntakia SultanaNo ratings yet

- Eng8019 4356Document4 pagesEng8019 4356zaven limNo ratings yet

- Phys5191 1641Document4 pagesPhys5191 1641BeniNo ratings yet

- Eng1709 5253Document4 pagesEng1709 5253Game HackerNo ratings yet

- Chem4599 3295Document4 pagesChem4599 3295Nathaniel Louise LuraNo ratings yet

- Eng2847 6426Document4 pagesEng2847 6426Bleng BongNo ratings yet

- Acc8009 1678Document4 pagesAcc8009 1678German QuiterioNo ratings yet

- Phys1122 7641Document4 pagesPhys1122 7641Raden AzharNo ratings yet

- Psy5750 3682Document4 pagesPsy5750 3682Kathleen Ivy AlfecheNo ratings yet

- Wasda3349 8834Document4 pagesWasda3349 8834simonrezkyNo ratings yet

- Soc4205 9037Document4 pagesSoc4205 9037Ovelia KayuzakiNo ratings yet

- House of DavidDocument11 pagesHouse of Davidapi-204785694No ratings yet

- Acc1013 1488Document4 pagesAcc1013 1488Andrés MartínezNo ratings yet

- Math6642 5235Document4 pagesMath6642 5235Rohan BasnetNo ratings yet

- Acc5086 9391Document4 pagesAcc5086 9391Lorraine GarabilloNo ratings yet

- Bio4412 6904Document4 pagesBio4412 6904Ericko Wahyu PratamaNo ratings yet

- Econ747 7247Document4 pagesEcon747 7247Fareed NazmiNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledLoi GangNo ratings yet

- Bio1393 9345Document4 pagesBio1393 9345JA YZ ELNo ratings yet

- Arch1398 8179Document4 pagesArch1398 8179ronskie zagadaNo ratings yet

- The Man Who Needed Two Graves PDFDocument61 pagesThe Man Who Needed Two Graves PDFkathleeneideNo ratings yet

- Bio8521 2637Document4 pagesBio8521 2637Rochman HijauNo ratings yet

- MNGT 6933Document4 pagesMNGT 6933NicoNo ratings yet

- Econ516 7566Document4 pagesEcon516 7566Ranier Andrei VillanuevaNo ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledDon RatbuNo ratings yet

- Acc7461 9647Document4 pagesAcc7461 9647upi karkiNo ratings yet

- Math5599 3814Document4 pagesMath5599 3814John Paul CabreraNo ratings yet

- Uas7455 6706Document4 pagesUas7455 6706Bagas KaraNo ratings yet

- Hist9859 9256Document4 pagesHist9859 9256Febrysna GuloNo ratings yet

- Math5599 3831Document4 pagesMath5599 3831John Paul CabreraNo ratings yet

- Soc2697 8234Document4 pagesSoc2697 8234TheBlindWardenNo ratings yet

- Math2473 618Document4 pagesMath2473 618Toshii Fid ReylNo ratings yet

- Phys Pe1088540 - 6569Document4 pagesPhys Pe1088540 - 6569Elton OdhiamboNo ratings yet

- Chem6753 9759Document4 pagesChem6753 9759KATRINA CAMILLE RAMOSNo ratings yet

- Chem1047 1894Document4 pagesChem1047 1894Juan Alcazar RomeroNo ratings yet

- Eng7083 5278Document4 pagesEng7083 5278John Paul CabreraNo ratings yet

- Acc3937 2620Document4 pagesAcc3937 2620afiq1229No ratings yet

- UntitledDocument4 pagesUntitledflorever maniaNo ratings yet

- Acc9805 6036Document4 pagesAcc9805 6036ananda SariNo ratings yet

- Chem3176 7861Document4 pagesChem3176 7861Annisa Putri MaharaniNo ratings yet

- Acc8685 3837Document4 pagesAcc8685 3837Fernandez, Rica Maye G.No ratings yet

- Matematika7499 3473Document4 pagesMatematika7499 3473Ajudan KeduaNo ratings yet

- Hist5847 1166Document4 pagesHist5847 1166Abel Gil ZamoraNo ratings yet

- Eng3477 2844Document4 pagesEng3477 2844Jeffrey Liel FerrerNo ratings yet

- The Anglo-Cimbri and Teutonic Races Proved To Be The Lost Tribes of Israel (1871) - by James RankinDocument12 pagesThe Anglo-Cimbri and Teutonic Races Proved To Be The Lost Tribes of Israel (1871) - by James RankinMarian MihuNo ratings yet

- The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 12, No. 337, October 25, 1828 by VariousDocument40 pagesThe Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction Volume 12, No. 337, October 25, 1828 by VariousGutenberg.orgNo ratings yet

- Math5816 1787Document4 pagesMath5816 1787Hilmy HabibiNo ratings yet

- Ipa 7583Document4 pagesIpa 7583FF ErizNo ratings yet

- MNGT 6939Document4 pagesMNGT 6939NicoNo ratings yet

- Chem2606 8921Document4 pagesChem2606 8921Rafa AlfaNo ratings yet

- Bcom 6524Document4 pagesBcom 6524Pauline KariaNo ratings yet

- En (1464)Document1 pageEn (1464)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Prospekt BGF PDFDocument150 pagesProspekt BGF PDFreacharunkNo ratings yet

- General Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsuranceDocument19 pagesGeneral Terms and Conditions of The Pzu NNW (Personal Accident Insurance Pzu Edukacja InsurancereacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1459)Document1 pageEn (1459)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- And Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atDocument1 pageAnd Rome.: in Front of The Prostyle Existed atreacharunkNo ratings yet

- Mate The: (Fig. - VrouldDocument1 pageMate The: (Fig. - VrouldreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1451)Document1 pageEn (1451)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1458)Document1 pageEn (1458)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1383)Document1 pageEn (1383)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1382)Document1 pageEn (1382)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1386)Document1 pageEn (1386)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- The The Jamb The Name Much The: Tlio CL - AssesDocument1 pageThe The Jamb The Name Much The: Tlio CL - AssesreacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1376)Document1 pageEn (1376)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- En (1374)Document1 pageEn (1374)reacharunkNo ratings yet

- Israels Identity It MattersDocument61 pagesIsraels Identity It MattersRome100% (1)

- Encountering JesusDocument9 pagesEncountering JesusKoCsevenofpoetryNo ratings yet

- Rite of Burning PalmsDocument5 pagesRite of Burning PalmsBamPanggatNo ratings yet

- NT16 The Lost Son USADocument16 pagesNT16 The Lost Son USACharles Gabriel COLANGGONo ratings yet

- Religion NotesDocument47 pagesReligion Notesapi-388942752No ratings yet

- Feast of TabernaclesDocument13 pagesFeast of TabernacleschuasioklengNo ratings yet

- Congregation Ohaiv Yisroel 2010 Annual Dinner JournalDocument80 pagesCongregation Ohaiv Yisroel 2010 Annual Dinner JournalShellyS2No ratings yet

- Personal Financial Planning 14th Edition Billingsley Solutions Manual 1Document36 pagesPersonal Financial Planning 14th Edition Billingsley Solutions Manual 1shirleybartlettndbyqeoaxi100% (37)

- The Secrets of Solomon's Temple, Discover The Hidden Truth That Lies at The Heart of Freemasonry - Kevin L GestDocument368 pagesThe Secrets of Solomon's Temple, Discover The Hidden Truth That Lies at The Heart of Freemasonry - Kevin L GestRaffaele Storino MacKinnon100% (3)

- Archangelic Seichim ReikiDocument12 pagesArchangelic Seichim ReikiĀryaFaṛzaneḥ100% (5)

- Honoring My ParentsDocument18 pagesHonoring My ParentsRon LangbayanNo ratings yet

- Covenant of GodDocument154 pagesCovenant of GodmarklutyNo ratings yet

- Girard and Theology Part IDocument8 pagesGirard and Theology Part IAlex Anghel100% (1)

- Behold A Moon Is BornDocument15 pagesBehold A Moon Is Bornmpox18681868No ratings yet

- SourcesDocument1 pageSourcesapi-353042906No ratings yet

- Early Church LeadershipDocument13 pagesEarly Church Leadershipigdelacruz84No ratings yet

- Revue Des Études Juives. 1880. Volume 56.Document330 pagesRevue Des Études Juives. 1880. Volume 56.Patrologia Latina, Graeca et OrientalisNo ratings yet

- 11 How The Little Horn Changed God's Law - EDItDocument79 pages11 How The Little Horn Changed God's Law - EDItJayhia Malaga JarlegaNo ratings yet

- Bibchron PDFDocument333 pagesBibchron PDFjoris57No ratings yet

- Rite of Burning of Palms and Preparing The AshesDocument3 pagesRite of Burning of Palms and Preparing The Ashesronel bayononNo ratings yet

- Act 2 Scene 9Document5 pagesAct 2 Scene 9besej41221No ratings yet

- The Two SeedsDocument44 pagesThe Two SeedsJeffrey Hidalgo100% (2)