0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

32 viewsG.R. No. L-14074, in Re Will of Riosa

G.R. No. L-14074, in Re Will of Riosa

Uploaded by

chibilexThis document discusses three rules for determining whether the law in effect at the time a will is executed or the law in effect at the time of death controls the will's validity. The court analyzes these rules and precedents from other jurisdictions before deciding that the will in this case, which was executed according to the law in effect at the time but not the law in effect at the time of death, is still valid. The court finds the reasoning behind applying the law at death to be flawed and that a will becomes a completed act upon valid execution, so subsequent changes in law should not invalidate it.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

G.R. No. L-14074, in Re Will of Riosa

G.R. No. L-14074, in Re Will of Riosa

Uploaded by

chibilex0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

32 views5 pagesThis document discusses three rules for determining whether the law in effect at the time a will is executed or the law in effect at the time of death controls the will's validity. The court analyzes these rules and precedents from other jurisdictions before deciding that the will in this case, which was executed according to the law in effect at the time but not the law in effect at the time of death, is still valid. The court finds the reasoning behind applying the law at death to be flawed and that a will becomes a completed act upon valid execution, so subsequent changes in law should not invalidate it.

Original Description:

hi

Original Title

G

Copyright

© © All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

This document discusses three rules for determining whether the law in effect at the time a will is executed or the law in effect at the time of death controls the will's validity. The court analyzes these rules and precedents from other jurisdictions before deciding that the will in this case, which was executed according to the law in effect at the time but not the law in effect at the time of death, is still valid. The court finds the reasoning behind applying the law at death to be flawed and that a will becomes a completed act upon valid execution, so subsequent changes in law should not invalidate it.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

0 ratings0% found this document useful (0 votes)

32 views5 pagesG.R. No. L-14074, in Re Will of Riosa

G.R. No. L-14074, in Re Will of Riosa

Uploaded by

chibilexThis document discusses three rules for determining whether the law in effect at the time a will is executed or the law in effect at the time of death controls the will's validity. The court analyzes these rules and precedents from other jurisdictions before deciding that the will in this case, which was executed according to the law in effect at the time but not the law in effect at the time of death, is still valid. The court finds the reasoning behind applying the law at death to be flawed and that a will becomes a completed act upon valid execution, so subsequent changes in law should not invalidate it.

Copyright:

© All Rights Reserved

Available Formats

Download as DOCX, PDF, TXT or read online from Scribd

Download as docx, pdf, or txt

You are on page 1of 5

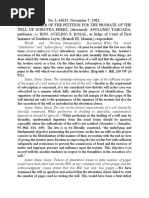

G.R. No.

L-14074, In re will of Riosa

November 7, 1918

G.R. No. L-14074

In the matter of the probation of the will of Jose Riosa. MARCELINO CASAS,

applicant-appellant,

MALCOLM, J .:

The issue which this appeal presents is whether in the Philippine Islands the law

existing on the date of the execution of a will, or the law existing at the death of the

testator, controls.

Jose Riosa died on April 17, 1917. He left a will made in the month of January, 1908,

in which he disposed of an estate valued at more than P35,000. The will was duly

executed in accordance with the law then in force, namely, section 618 of the Code of

Civil Procedure. The will was not executed in accordance with Act No. 2645,

amendatory of said section 618, prescribing certain additional formalities for the

signing and attestation of wills, in force on and after July 1, 1916. In other words, the

will was in writing, signed by the testator, and attested and subscribed by three

credible witnesses in the presence of the testator and of each other; but was not signed

by the testator and the witnesses on the left margin of each and every page, nor did the

attestation state these facts. The new law, therefore, went into effect after the making

of the will and before the death of the testator, without the testator having left a will

that conforms to the new requirements.

Section 618 of the Code of Civil Procedure reads:

No will, except as provided in the preceding section, shall be valid to pass any estate,

real or personal, nor charge or affect the same, unless it be in writing and signed by

the testator, or by the testator's name written by some other person in his presence,

and by his express direction, and attested and subscribed by three or more credible

witnesses in the presence of the testator and of each other. The attestation shall state

the fact that the testator signed the will, or caused it to be signed by some other

person, at his express direction, in the presence of three witnesses, and that they

attested and subscribed it in his presence and in the presence of each other. But the

absence of such form of attestation shall not render the will invalid if it is proven that

the will was in fact signed and attested as in this section provided.

Act No. 2645 has amended section 618 of the Code of Civil Procedure so as to make

said section read as follows:

SEC. 618. Requisites of will. - No will, except as provided in the preceding section,

shall be valid to pass any estate, real or personal, nor charge or affect the same, unless

it be written in the language or dialect known by the testator and signed by him, or by

the testator's name written by some other person in his presence, and by his express

direction, and attested and subscribed by three or more credible witnesses in the

presence of the testator and of each other. The testator or the person requested by him

to write his name and the instrumental witnesses of the will, shall also sign, as

aforesaid, each, and every page thereof, on the left margin, and said pages shall be

numbered correlatively in letters placed on the upper part of each sheet. The

attestation shall state the number of sheets or pages used, upon which the will is

written, and the fact that the testator signed the will and every page thereof, or caused

some other person to write his name, under his express direction, in the presence of

three witnesses, and the latter witnessed and signed the will and all pages thereof in

the presence of the testator and of each other.

This court has heretofore held in a decision handed down by the Chief Justice, as to a

will made after the date Act No. 2645 went into effect, that it must comply with the

provisions of this law. (Caraig vs Tatlonghari, R. G. No. 12558, dated March 23, 1918

[not published].) The court has further held in a decision handed down by Justice

Torres, as to will executed by a testator whose death took place prior to the operative

date of Act No. 2645, that the amendatory act is inapplicable. (Bona vs. Briones,

[1918], 38 Phil., 276.) The instant appeal presents an entirely different question. The

will was execute prior to the enactment of Act No. 2645 and the death occurred after

the enactment of this law.

There is a clear cleavage of authority among the cases and the text-writers, as to the

effect of a change in the statutes prescribing the formalities necessary to be observed

in the execution of a will, when such change is made intermediate to the execution of

a will and the death of a testator. (See generally 40 Cyc., 1076. and any textbook on

Wills, and Lane's Appeal from Probate [1889], 57 Conn., 182.) The rule laid down by

the courts in many jurisdictions is that the statutes in force at the testator's death are

controlling, and that a will not executed in conformity with such statutes is invalid,

although its execution was sufficient at the time it was made. The reasons assigned for

applying the later statute are the following: "As until the death of the testator the paper

executed by him, expressing his wishes, is not a will, but a mere inchoate act which

may or may not be a will, the law in force at the testator's death applies and controls

the proof of the will." (Sutton vs. Chenault [1855], 18 Ga., 1.) Were we to accept the

foregoing proposition and the reasons assigned for it, it would logically result that the

will of Jose Riosa would have to be held invalid.

The rule prevailing in many other jurisdictions is that the validity of the execution of a

will must be tested by the statutes in force at the time of its execution and that statutes

subsequently enacted have no retrospective effect. This doctrine is believed to be

supported by the weight of authority. It was the old English view; in Downs (or

Downing) vs. Townsend (Ambler, 280), Lord Hardwicke is reported to have said that

"the general rule as to testaments is, that the time of the testament, and not the

testator's death, is regarded." It is also the modern view, including among other

decisions one of the Supreme Court of Vermont from which State many of the

sections of the Code if Civil Procedure of the Philippine Islands relating to wills are

taken. (Giddings vs. Turgeon [1886], 58 Vt., 103.)

Of the numerous decisions of divergent tendencies, the opinion by the learned Justice

Sharswood (Taylor vs. Mitchell [1868], 57 Pa. St., 209) is regarded to be the best

considered. In this opinion is found the following:

Retrospective laws generally if not universally work injustice, and ought to be so

construed only when the mandate of the legislature is imperative. When a testator

makes a will, formally executed according to the requirements of the law existing at

the time of its execution, it would unjustly disappoint his lawful right of disposition to

apply to it a rule subsequently enacted, though before his death.

While it is true that every one is presumed to know the law, the maxim in fact is

inapplicable to such a case; for he would have an equal right to presume that no new

law would affect his past act, and rest satisfied in security on that presumption. . . . It

is true, that every will is ambulatory until the death of the testator, and the disposition

made by it does not actually take effect until then. General words apply to the

property of which the testator dies possessed, and he retains the power of revocation

as long as he lives. The act of bequeathing or devising, however, takes place when the

will is executed, though to go into effect at a future time.

A third view, somewhat larger in conception than the preceding one, finding support

in the States of Alabama and New York, is that statutes relating to the execution of

wills, when they increase the necessary formalities, should be construed so as not to

impair the validity of a will already made and, when they lessen the formalities

required, should be construed so as to aid wills defectively executed according to the

law in force at the time of their making (Hoffman vs. Hoffman, [1855], 26 Ala., 535;

Price vs. Brown, 1 Bradf., Surr. N.Y., 252.)

This court is given the opportunity to choose between the three rules above described.

Our selection, under such circumstances, should naturally depend more on reason than

on technicality. Above all, we cannot lose sight of the fact that the testator has

provided in detail for the disposition of his property and that his desires should be

respected by the courts. Justice is a powerful pleader for the second and third rules on

the subject.

The plausible reasoning of the authorities which back the first proposition is, we

think, fallacious. The act of bequeathing or devising is something more than inchoate

or ambulatory. In reality, it becomes a completed act when the will is executed and

attested according to the law, although it does not take effect on the property until a

future time.

It is, of course, a general rule of statutory construction, as this court has said, that "all

statutes are to be construed as having only a prospective operation unless the purpose

and intention of the Legislature to give them a retrospective effect is expressly

declared or is necessarily implied from the language used. In every case of doubt, the

doubt must be resolved against the restrospective effect." (Montilla vs. Corporacion

de PP. Agustinos [1913], 24 Phil., 220. See also Chew Heong vs. U.S. [1884], 112

U.S., 536; U.S. vs American Sugar Ref. Co. [1906], 202 U.S., 563.) Statute law, as

found in the Civil Code, is corroborative; article 3 thereof provides that "laws shall

not have a retroactive effect, unless therein otherwise prescribed." The language of

Act No. 2645 gives no indication of retrospective effect. Such, likewise, has been the

uniform tendency of the Supreme Court of the Philippine Islands on cases having

special application to testamentary succession. (Abello vs. Kock de Monaterio

[1904], 3 Phil., 558; Timbol vs. Manalo [1906], 6 Phil., 254; Bona vs. Briones, supra;

In the Matter of the Probation of the Will of Bibiana Diqui?a [1918], R. G. No. 13176,

1 concerning the language of the Will. See also section 617, Code of Civil Procedure.)

The strongest argument against our accepting the first two rules comes out of section

634 of the Code of Civil Procedure which, in negative terms, provides that a will shall

be disallowed in either of five cases, the first being "if not executed and attested as in

this Act provided." Act No. 2645 has, of course, become part and parcel of the Code

of Civil Procedure. The will in question is admittedly not executed and attested as

provided by the Code of Civil Procedure as amended. Nevertheless, it is proper to

observe that the general principle in the law of wills inserts itself even within the

provisions of said section 634. Our statute announces a positive rule for the

transference of property which must be complied with as completed act at the time of

the execution, so far as the act of the testator is concerned, as to all testaments made

subsequent to the enactment of Act No. 2645, but is not effective as to testaments

made antecedent to that date.

To answer the question with which we began this decision, we adopt as our own the

second rule, particularly as established by the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania. The

will of Jose Riosa is valid.

The order of the Court of First Instance for the Province of Albay of December 29,

1917, disallowing the will of Jose Riosa, is reversed, and the record shall be returned

to the lower court with direction to admit the said will to probate, without special

findings as to costs. So ordered.

Arellano, C.J., Torres, Johnson, Street, Avance?a and Fisher, JJ., concur.

You might also like

- Epublic of The PhilippinesDocument4 pagesEpublic of The PhilippineschibilexNo ratings yet

- Vicente de Vera For Petitioner-AppellantDocument10 pagesVicente de Vera For Petitioner-AppellantSopongco ColeenNo ratings yet

- Will of Jose Riosa - GR No L-14074Document2 pagesWill of Jose Riosa - GR No L-14074Sopongco ColeenNo ratings yet

- In Re Will of RiosaDocument6 pagesIn Re Will of RiosaPrincess Trisha Joy UyNo ratings yet

- In Re Will of RiosaDocument3 pagesIn Re Will of RiosabalderaselizNo ratings yet

- In Re. Probate of Will of Jose RiosaDocument4 pagesIn Re. Probate of Will of Jose RiosaHudson CeeNo ratings yet

- In Re: Will of RiosaDocument2 pagesIn Re: Will of Riosahmn_scribdNo ratings yet

- In Re Will of Riosa Enrique V AbadiaDocument3 pagesIn Re Will of Riosa Enrique V AbadiaJesi CarlosNo ratings yet

- In Re Will of RiosaDocument3 pagesIn Re Will of RiosaEunice Valeriano GuadalopeNo ratings yet

- In Re Will of RiosaDocument3 pagesIn Re Will of RiosaCyruz TuppalNo ratings yet

- In The Matter of The Probation of The Will of Jose RiosaDocument3 pagesIn The Matter of The Probation of The Will of Jose RiosaMacNo ratings yet

- Succession Case DigestsDocument9 pagesSuccession Case DigestsCMGNo ratings yet

- Digest - Taboado v. RosalDocument2 pagesDigest - Taboado v. RosalDaph Villegas100% (1)

- De Molo v. Molo GR No. L-2538 Sept 21, 1051Document2 pagesDe Molo v. Molo GR No. L-2538 Sept 21, 1051Cherry ChaoNo ratings yet

- Aldaba vs. RoqueDocument2 pagesAldaba vs. RoqueErmeline TampusNo ratings yet

- Beltran V RamosDocument5 pagesBeltran V RamosJenniferPizarrasCadiz-CarullaNo ratings yet

- LASAM VsDocument1 pageLASAM VsLisa RobbinsNo ratings yet

- Extrinsic Validity of WillsDocument2 pagesExtrinsic Validity of WillsNimpa PichayNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 1439 March 19, 1904 ANTONIO CASTAÑEDA, Plaintiff-Appellee, JOSE E. ALEMANY, Defendant-AppellantDocument19 pagesG.R. No. 1439 March 19, 1904 ANTONIO CASTAÑEDA, Plaintiff-Appellee, JOSE E. ALEMANY, Defendant-Appellantjerico kier nonoNo ratings yet

- Supreme Court: Gregorio P. Formoso and Vicente Formoso For Petitioner. The Respondents in Their Own BehalfDocument8 pagesSupreme Court: Gregorio P. Formoso and Vicente Formoso For Petitioner. The Respondents in Their Own BehalfgheljoshNo ratings yet

- 23 Beltran V SamsonDocument5 pages23 Beltran V SamsonArjay ElnasNo ratings yet

- Beltran Vs SamsonDocument4 pagesBeltran Vs Samsonzedric santosNo ratings yet

- Perez Vs Rosal PDFDocument5 pagesPerez Vs Rosal PDFjeandpmdNo ratings yet

- Alaban vs. CA (GR: 156021) : Causa Can Be Clearly Deduced From The Terms of The Instrument, and While It Does NotDocument3 pagesAlaban vs. CA (GR: 156021) : Causa Can Be Clearly Deduced From The Terms of The Instrument, and While It Does NotAJ QuimNo ratings yet

- Francisco Beltran Vs Felix Samson 53 Phil 570Document4 pagesFrancisco Beltran Vs Felix Samson 53 Phil 570Nunugom SonNo ratings yet

- in Re Will of Rev. AbadiaDocument3 pagesin Re Will of Rev. AbadiaMarie ReloxNo ratings yet

- Taboada v. RosalDocument5 pagesTaboada v. RosalmisterdodiNo ratings yet

- Beltran Vs Samson and JoseDocument6 pagesBeltran Vs Samson and JoseJenifferRimandoNo ratings yet

- in Re Will of RiosaDocument1 pagein Re Will of Riosajerico kier nonoNo ratings yet

- Beltran vs. SamsonDocument4 pagesBeltran vs. SamsonMJ BautistaNo ratings yet

- Succession CasesDocument12 pagesSuccession CasesJeMae MaNo ratings yet

- Cruz Vs VillasorDocument4 pagesCruz Vs VillasorIvan Montealegre ConchasNo ratings yet

- Beltran Vs SamsonDocument5 pagesBeltran Vs SamsonGen CabrillasNo ratings yet

- Selover, Bates & Co. v. Walsh, 226 U.S. 112 (1912)Document5 pagesSelover, Bates & Co. v. Walsh, 226 U.S. 112 (1912)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- LegForms ReportDocument23 pagesLegForms ReportVikki AmorioNo ratings yet

- (Case Digest by Zenfanie Sandoval) : Barut vs. Cagacungan FactsDocument6 pages(Case Digest by Zenfanie Sandoval) : Barut vs. Cagacungan FactsJan NiñoNo ratings yet

- Lasam V UmenganDocument2 pagesLasam V UmenganTom Lui EstrellaNo ratings yet

- Erasmo M. Diola Counsel For Petition. Hon. Avelino S. Rosal in His Own BehalfDocument6 pagesErasmo M. Diola Counsel For Petition. Hon. Avelino S. Rosal in His Own BehalfSimeon SuanNo ratings yet

- Testamentary Provisions As Affected by The Rules of Private InterDocument9 pagesTestamentary Provisions As Affected by The Rules of Private InterDavid john hakimuNo ratings yet

- Cagro Vs CagroDocument3 pagesCagro Vs Cagrolen_dy010487No ratings yet

- G.R. No. 32025 September 23, 1929Document4 pagesG.R. No. 32025 September 23, 1929analou agustin villezaNo ratings yet

- Testate Estate of CARLOS GIL, Deceased. ISABEL HERRERO VDA. DE GIL, Administratrix-Appellee, vs. PILAR GIL VDA. DE MURCIANO, Oppositor-AppellantDocument5 pagesTestate Estate of CARLOS GIL, Deceased. ISABEL HERRERO VDA. DE GIL, Administratrix-Appellee, vs. PILAR GIL VDA. DE MURCIANO, Oppositor-AppellantRegina ZagalaNo ratings yet

- Barut Vs Cabacungan G.R. No. L-6285 February 15, 1912Document3 pagesBarut Vs Cabacungan G.R. No. L-6285 February 15, 1912Gui PeNo ratings yet

- Conditional Acceptance-Aka Yall Done Fucked UDocument12 pagesConditional Acceptance-Aka Yall Done Fucked UGreg100% (1)

- Alonzo vs. PaduaDocument6 pagesAlonzo vs. PaduaDanielle AlonzoNo ratings yet

- Beltran v. Samson, 53 Phil 570 (1929)Document3 pagesBeltran v. Samson, 53 Phil 570 (1929)Arkhaye SalvatoreNo ratings yet

- Enriquez Vs Abadia DigestDocument2 pagesEnriquez Vs Abadia DigestHenteLAWco100% (1)

- Barut Vs CabacunganDocument7 pagesBarut Vs CabacunganCharm Divina LascotaNo ratings yet

- Cole V Cunningham - 133 U.S. 107 (1890)Document13 pagesCole V Cunningham - 133 U.S. 107 (1890)Dan GoodmanNo ratings yet

- Taboada Vs RosalDocument6 pagesTaboada Vs RosalIvan Montealegre ConchasNo ratings yet

- Ennis Water Works v. Ennis, 233 U.S. 652 (1914)Document4 pagesEnnis Water Works v. Ennis, 233 U.S. 652 (1914)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Barut v. Cabacungan, G.R. No. 6285, (February 15, 1912), 21 PHIL 461-473)Document9 pagesBarut v. Cabacungan, G.R. No. 6285, (February 15, 1912), 21 PHIL 461-473)yasuren2No ratings yet

- In Re Will of RiosaDocument2 pagesIn Re Will of RiosaDaniela SandraNo ratings yet

- United States Vs de GuzmanDocument7 pagesUnited States Vs de GuzmanKael MarmaladeNo ratings yet

- Perpetuo L.B. Alonzo For Petitioners. Luis R. Reyes For Private RespondentDocument4 pagesPerpetuo L.B. Alonzo For Petitioners. Luis R. Reyes For Private RespondentGol LumNo ratings yet

- Cases 13-18Document16 pagesCases 13-18Janette SumagaysayNo ratings yet

- Leitensdorfer v. Webb, 61 U.S. 176 (1858)Document10 pagesLeitensdorfer v. Webb, 61 U.S. 176 (1858)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Barut Vs CabacunganDocument7 pagesBarut Vs CabacunganJusio Rae ReyesNo ratings yet

- Taboada v. RosalDocument8 pagesTaboada v. RosaltheagNo ratings yet

- Slide 3. G. 1Document13 pagesSlide 3. G. 1chibilexNo ratings yet

- Supreme CourtDocument14 pagesSupreme CourtchibilexNo ratings yet

- DSGSGDocument58 pagesDSGSGchibilexNo ratings yet

- 2014 Civ1 List of Cases 7-10-14Document7 pages2014 Civ1 List of Cases 7-10-14chibilexNo ratings yet

- DGDHHDocument58 pagesDGDHHchibilexNo ratings yet

- Facts:: Land LotDocument13 pagesFacts:: Land LotchibilexNo ratings yet

- Objectives: To Determine If A Relation Is A Function To Find The Domain and Range of A Function To Evaluate FunctionsDocument35 pagesObjectives: To Determine If A Relation Is A Function To Find The Domain and Range of A Function To Evaluate FunctionschibilexNo ratings yet

- Office of The City AssessorDocument5 pagesOffice of The City AssessorchibilexNo ratings yet

- Family Law Application Form: Paul - Burns@law - Ox.ac - UkDocument1 pageFamily Law Application Form: Paul - Burns@law - Ox.ac - UkchibilexNo ratings yet

- Corp. Law Outline 3 (2020)Document3 pagesCorp. Law Outline 3 (2020)Effy SantosNo ratings yet

- William Thompson v. Coastal Oil Company, 352 U.S. 862 (1956)Document1 pageWilliam Thompson v. Coastal Oil Company, 352 U.S. 862 (1956)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Iran Juin 2011Document288 pagesIran Juin 2011Parvèz DookhyNo ratings yet

- Cyber LawDocument16 pagesCyber LawPrateethi SinghviNo ratings yet

- Sweet & Maxwell Group House StyleDocument10 pagesSweet & Maxwell Group House Styleapi-28040692No ratings yet

- Nalsar PDFDocument25 pagesNalsar PDFPADMANABHAN POTTINo ratings yet

- Barbara Ann Alley and W.H. Alley, Cross-Appellees v. Gubser Development Company, National Gypsum Company and Weyerhaeuser Company, Cross-Appellants, 785 F.2d 849, 10th Cir. (1986)Document12 pagesBarbara Ann Alley and W.H. Alley, Cross-Appellees v. Gubser Development Company, National Gypsum Company and Weyerhaeuser Company, Cross-Appellants, 785 F.2d 849, 10th Cir. (1986)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- My Report 1Document71 pagesMy Report 1junjun camonasNo ratings yet

- Moot MemorialDocument38 pagesMoot MemorialKandlagunta Gayathri PraharshithaNo ratings yet

- 105 Communities Cagayan, Inc. vs. NanolDocument2 pages105 Communities Cagayan, Inc. vs. NanolJemNo ratings yet

- Cases For March 11Document10 pagesCases For March 11Patrick RamosNo ratings yet

- Wire Perimeter Fence With Concrete PostDocument2 pagesWire Perimeter Fence With Concrete PostHarold de Mesa100% (1)

- Beyond The Contours of Normally Acceptable AA AGBOR & EE NJIEASSAM PER: PELJ 2019Document32 pagesBeyond The Contours of Normally Acceptable AA AGBOR & EE NJIEASSAM PER: PELJ 2019Karen LunaNo ratings yet

- WV-02 Lake Research Partners For Mark Hunt (Sept 2016)Document1 pageWV-02 Lake Research Partners For Mark Hunt (Sept 2016)Daily Kos ElectionsNo ratings yet

- Prostitution and AbortionDocument33 pagesProstitution and Abortioncat03_katrina91No ratings yet

- CAP117A - Supreme Court of Judicature PDFDocument57 pagesCAP117A - Supreme Court of Judicature PDFCourtni HolderNo ratings yet

- Revenue Survey and Assessment, Bombay, 1869Document270 pagesRevenue Survey and Assessment, Bombay, 1869snaponumesh0% (1)

- People vs. AlcongaDocument5 pagesPeople vs. AlcongaDaphnie CuasayNo ratings yet

- Decision No. 2018-294 DTD March 15 2018 PDFDocument6 pagesDecision No. 2018-294 DTD March 15 2018 PDFAnj EboraNo ratings yet

- 5 - Tanda vs. AldayaDocument1 page5 - Tanda vs. AldayaJavior PinlacNo ratings yet

- Appeal Coa Disallowance 2021Document14 pagesAppeal Coa Disallowance 2021Maryknoll MaltoNo ratings yet

- United States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitDocument3 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals, Second CircuitScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Plaintiffs-Appellees vs. vs. Defendants-Appellants Castelo & Suck Jose Q CalingoDocument9 pagesPlaintiffs-Appellees vs. vs. Defendants-Appellants Castelo & Suck Jose Q CalingoMark Catabijan CarriedoNo ratings yet

- FIFA World Cup South Africa 2010™: Electronic WallchartDocument9 pagesFIFA World Cup South Africa 2010™: Electronic Wallchartpramd26No ratings yet

- Reviewer On Criminal LawDocument46 pagesReviewer On Criminal LawLaurie Carr LandichoNo ratings yet

- 168279-2013-Chu v. Mach Asia Trading Corp.Document6 pages168279-2013-Chu v. Mach Asia Trading Corp.Nichole Patricia PedriñaNo ratings yet

- 7e's Lesson-Plan Grade 10 - OJT 3 - Gay - Lussac LawDocument8 pages7e's Lesson-Plan Grade 10 - OJT 3 - Gay - Lussac LawDennard LomugdangNo ratings yet

- Declaration of IndependenceDocument6 pagesDeclaration of Independencetmjsu13No ratings yet

- Comilang v. BelenDocument16 pagesComilang v. BelenRogelio BataclanNo ratings yet

- Ibrar Assigment Business LawDocument4 pagesIbrar Assigment Business LawMD OsmanNo ratings yet