044040387

044040387

Uploaded by

Hykma Purple CliquersPharmacyCopyright:

Available Formats

044040387

044040387

Uploaded by

Hykma Purple CliquersPharmacyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

044040387

044040387

Uploaded by

Hykma Purple CliquersPharmacyCopyright:

Available Formats

Three-Day Course of

Oral Azithromycin vs Topical Oxytetracycline/

Polymyxin in Treatment of Active Endemic Trachoma

Mustafa Guzey,* Gonul Aslan,

Ilyas Ozardali, Emel Basar, Ahmet Satici* and Sezin Karadede*

Departments of *Ophthalmology, Clinical Microbiology,

Pathology, Harran University School of Medicine, Sanliurfa, Turkey; Department

of Ophthalmology, Istanbul University, Cerrahpasa School of Medicine, Istanbul, Turkey

Purpose: The aim of this study on endemic trachoma was to carry out a comparison of

azithromycin (3-day course, oral dose of 10 mg/kg per day) with conventional treatment

(topical oxytetracycline/polymyxin ointment; twice a day for 2 months) in a rural area near

Sanliurfa, Turkey.

Methods: Ninety-six subjects with active trachoma were randomly assigned conventional or

azithromycin treatment. Subjects were examined 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after the start of treatment. Clinical findings were recorded for each eye. Swabs were taken from upper eyelids

3 and 6 months after the start of treatment for direct fluorescein antibody test.

Results: By six-month follow-up, trachoma had resolved clinically in 43 (89.58%) of the 48

subjects who received azithromycin, compared with 33 (68.75%) of the 48 who were treated

conventionally. Microbiological success rates (direct fluorescein antibody test negativity)

were 83.33% in the azithromycin group and 62.50% in the conventional therapy group.

Compliance with both treatments was good. By 6 months, 14.58% of the subjects in azithromycin group and 33.33% of the subjects in the topical treatment group were reinfected.

There were significant differences in the efficacy of the treatment effects and the re-emergence of disease between the two treatment groups. Azithromycin was well-tolerated.

Conclusions: These results indicate that azithromycin may be an effective alternative for patients with active trachoma. As a systemic treatment, a 3-day course oral dose has important

potential for trachoma control. Jpn J Ophthalmol 2000;44:387391 2000 Japanese

Ophthalmological Society

Key Words: Azithromycin, oxytetracycline/polymyxin, trachoma.

Introduction

Trachoma, an ocular infection caused by Chlamydia

trachomatis, is the second leading cause of blindness

worldwide. Active trachoma occurs predominantly in

children in hyperendemic communities, with the risk

of blinding complications occurring in middle-aged

and older adults.1,2 Although trachoma has been

controlled in some areas, predictions based on de-

Received: June 16, 1999

Correspondence and reprint requests to: Mustafa GUZEY,

MD, Forsa Sok. Guney Apt. No. 21 Daire 1 Senesenevler,

Bostanci, Istanbul, Turkey

Jpn J Ophthalmol 44, 387391 (2000)

2000 Japanese Ophthalmological Society

Published by Elsevier Science Inc.

mographic trends suggest that the burden of both infection and blindness is likely to increase.3 There is a

need for effective intervention to control ocular

Chlamydia trachomatis infections.

The currently recommended treatment of trachoma

is topical tetracycline eye ointment for at least 6 weeks,

or on 5 consecutive days a month for 6 months.4 It is

suggested that subjects with a severe form of the disease should, in some circumstances, receive systemic

therapy. There is a wide spectrum of opinion among

trachoma experts about the effectiveness of these recommendations, reflecting a scarcity of data from controlled trials in endemic areas on which rational decisions about therapy can be based.5,6

0021-5155/00/$see front matter

PII S0021-5155(00)00167-2

388

Jpn J Ophthalmol

Vol 44: 387391, 2000

There are several reasons why this treatment is

less than satisfactory. It is difficult to apply ointment

to the eyes of young children. The ointment can

cause discomfort or blurring of vision and melts under conditions of high ambient temperature. Many

infected children have no symptoms and even in circumstances where ointment is given free it can be

difficult to motivate parents to continue treatment

for the stipulated period. A systemic treatment

effective in a short period would thus represent a

substantial advance in the chemotherapy of active

trachoma.

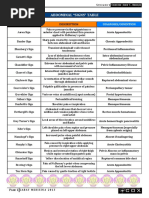

Azithromycin is a recently approved azalide antibiotic with the molecular formula of C38H72N2O12,

and a molecular weight of 749.00. It is a derivative of

erythromycin, containing an extra methyl-substituted nitrogen at position 9a in the lactone ring (Figure 1). This modification confers good bioavailability, with sustained high tissue concentrations after an

oral dose. Azithromycin achieves high concentrations in phagocytic cells and in fibroblasts. It appears

that fibroblasts serve as a reservoir of azithromycin

in tissues, allowing activity against organisms and

possibly transferring the antibiotic to phagocytic

cells for activity against intracellular pathogens and

delivery to infection sites.7 The high macrophage

and tissue concentration of the drug and prolonged

half-life suggest that azithromycin could potentially

be used in shorter treatment regimens.8,9 The present

study compared the clinical and microbiological efficacy and safety of a 3-day course of azithromycin

with a conventional 8-week course of topical oxytetracycline/polymyxin for the treatment of young patients with active ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infection.

Materials and Methods

In April 1998, an ocular survey was done in four

villages of Sanliurfa by a trained observer (MG).

The everted upper lids of both eyes were examined

with a binocular magnifying loupe. Findings were

graded according to the simplified World Health Organization grading system.10 Ninety-six subjects with

bilateral active trachoma or showing the symptoms

given below were selected. The existence of an active trachoma was clinically characterized by the

presence of at least 5 follicles associated with a papillary hypertrophy of the upper tarsal conjunctiva and

microbiologically characterized by the presence of at

least 5 elementary bodies per direct fluorescein antibody test slide. Clinical signs and symptoms taken

into consideration were follicular conjunctivitis and

Figure 1. Chemical structure of azithromycin.

papillary hypertrophy of the upper tarsal conjunctiva

with discharge, redness, irritation and burning-stinging

sensation and eyelid swelling.

Ninety-six patients were randomly assigned conventional or azithromycin treatment. Randomization was by room, all active cases within a room receiving the same treatment. Baseline eye swabs were

taken from all patients before treatment.

Expected effects, side effects, advantages, and disadvantages of both treatment methods were explained to patients who participated in the study

and/or their parents, and informed consent was

obtained.

Azithromycin suspension (200 mg/5 mL, Zitromax; Pfizer, Istanbul, Turkey) administered as a

3-day course (10 mg/kg per day) by mouth; a syringe

was used for measurement and administration. Subjects randomized for conventional treatment were

administered 0.5% oxytetracycline HCl/polymyxin

eye ointment (Terramycin, 5 mg/g oxytetracycline

HCl, 1 mg/g/polymyxin B sulfate; Pfizer) to each eye

twice daily for 8 weeks.

Possible side effects were investigated in both

groups by means of a standard interview, 7 days after

treatment started. The interview protocol contained

both specific questions about gastrointestinal symptoms in the preceding 7 days and open questions

about the general health of the subjects. At subsequent follow-up, mothers were questioned about the

general health of the subjects and any adverse events

recorded.

The following laboratory tests for safety evaluation were obtained at baseline and at weeks 2 and 4:

complete blood count with differential and platelet

counts, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, gamma glutamyl transferase, alanine

aminotransferase, aspartate aminotransferase, alkaline phosphatase, serum bilirubin, lactate dehydro-

389

M. GUZEY ET AL.

ORAL AZITHROMYCIN VS TOPICAL OXYTETRACYCLINE

genase, blood urea nitrogen, serum creatinine, serum calcium and phosphorus, electrolytes, total

protein, albumin, blood glucose, uric acid, serum

cholesterol, and urinalysis.

Conventional treatment was applied by the patients mothers, supervised by a trained nurse. Compliance with conventional treatment was assessed by

a system of witnessed treatments; the subjects name

was written on a form each time a treatment was witnessed. More than 95% of scheduled treatments

were witnessed.

Subjects were examined 1, 2, 3, and 6 months after

the start of treatment. Clinical findings were recorded for each eye. Swabs were taken from upper

eyelids 3 and 6 months after the start of treatment. A

dacron swab was rubbed on the everted upper tarsal

conjunctiva, after which it was rolled on a slide for

the direct antibody immunofluorescence test. Methanol-fixed slides were stained with monoclonal-fluorescein isothiocyanate antibody conjugate to the

major outer membrane protein. Smears were considered positive if 5 or more elementary bodies per

slide were seen.11

Noticeable symptomatic relief and considerable

resolution of clinical signs (disappearance of papillary hypertrophy, decrease in the number and size of

follicles) were considered as clinical success, and a

negative direct fluorescein antibody test was accepted as microbiological success.

In cases where this test was negative in the third

month, a positive test result obtained in the sixth

month was considered as the establishment of a reinfection, whether a noticeable re-appearance of clinical signs and symptoms was present or not. For statistical analysis of the results, the chi-square test was

used to compare the treatment groups.

Results

There were 96 subjects aged from 2 to 18 years

(Table 1). The treatment groups did not differ significantly in age or sex distribution.

Symptoms of diarrhea, vomiting, and abdominal

pain occurred in the azithromycin group (Table 2).

There were no serious adverse reactions and both

treatments were well-tolerated. No abnormalities

were determined in the laboratory test results. All

symptoms resolved spontaneously and none required

treatment. Compliance with conventional treatment

was extremely good. Local adverse reactions were

not seen in the conventional therapy group.

At 3 months, the clinical signs of 44 (91.67%) subjects in the azithromycin group and the clinical signs

Table 1. Baseline Comparisons of

Treatment Groups

Age (year)

and Sex

5

58

912

13

M/F

Azithromycin*

(n 48)

Conventional*

(n 48)

10 (20.83)

23 (47.92)

12 (25)

3 (6.25)

22/26

12 (25)

21 (43.75)

10 (20.83)

5 (10.42)

25/23

*Values in parentheses are percentages.

of 36 (75.00%) subjects in the conventional treatment group had resolved (P .029). These rates

were 89.58% and 68.75% at 6 months, respectively

(P .012) (Table 3). The rate of reinfection by 6

months was 33.33% in the conventional treatment

group, as opposed to 14.58% in the azithromycin

group, and the difference was statistically significant

(P .027). Antigen positivity at baseline and severe

or moderate disease were associated with persistence of clinical signs, and there was a tendency for

younger patients to have more persistent clinical

signs.

There were significant differences in the prevalence of direct fluorescein antibody test positivity in

ocular swabs between the therapy modalities (Table 4).

Discussion

Trachoma is a common disease that has disappeared in many parts of the world because of improved living conditions and hygiene. In trachomaendemic areas, severe disease leading to scarring and

blindness may be the result of frequent reinfection

or persistent infection in those whose immune system does not mount an adequate response to clear

the infection. Trachoma continues to be a serious

public health threat in southeast Turkey.12,13 Chlamydia trachomatis is an intracytoplasmic parasite and

has a unique, long, life cycle. Chlamydia shows two

Table 2. Adverse Events Survey 7 Days After

Azithromycin Treatment

Adverse Events

Abdominal pain

Diarrhea

Vomiting

Headache/body pain

Poor appetite

Fever

Number of Cases*

10 (20.83)

5 (10.42)

3 (6.25)

2 (4.17)

2 (4.17)

1 (2.08)

*Values in parentheses are percentages.

390

Jpn J Ophthalmol

Vol 44: 387391, 2000

Table 3. Clinical Success Rate (Resolution of Clinical

Signs) in Azithromycin and Conventional Treatment

Groups 3 and 6 Months After Start of Treatment

Time

3 months

6 months

Azithromycin*

(n 48)

44 (91.67)

43 (89.58)

Conventional*

(n 48)

36 (75.00)

33 (68.75)

Table 4. Microbiological Success Rate (Direct Fluorescein

Antibody Test Negativity) in Azithromycin and

Conventional Treatment Groups 3 and 6 Months After

Start of Treatment

Chi-Square

4.80

6.32

*Values in parentheses are percentages.

P .029.

P .012.

distinctive forms during its life cycle: the elementary

body and the reticulate body. The elementary body

is an infectious particle that initiates its infectious cycle by attaching to the surface of a susceptible cell.

Over a period of 68 hours, the particle enlarges,

and undergoes reorganization to become a reticulate

body. The reticulate body is noninfectious but metabolically active. Anti-chlamydial agents are only effective against reticulate bodies. These agents must

penetrate into the cell, cytoplasmic inclusions, and finally into the reticulate body itself. Moreover, they

must be maintained at high concentrations in tissues

for a long period of time. Effective anti-chlamydial

agents include tetracyclines, macrolides, and some of

the fluoroquinolones.14

Recent advances in diagnostic and screening technology and azithromycin therapy will likely have a

significant impact on the efficacy of disease control

programs and the opportunity for eventual disease

eradication. Azithromycin, with a half-life of 5 to 7

days, has excellent pharmacokinetic characteristics,

such as increased bioavailability, lower incidence of

gastrointestinal tract side effects, and increased concentration in mucus, macrophages, and tissues.15

These characteristics allow for short course or single

dosing, which alleviates the problem of patient noncompliance with multi-day regimens. The difficulty

of applying ointment to the eyes of young children,

the discomfort associated with its use, and the frequency of symptomless infection are other reasons

for the failure of control programs based on topical

therapy.

In this study, the 3-day course oral dose of azithromycin cured 83.33% of subjects with active trachoma

by 6 months and was more effective than the conventional treatment. Possible adverse effects of the

treatment were not serious and compliance was good

in azithromycin-treated subjects. These observations

have important implications for the control of

trachoma.

Chumbley et al16 suggested that there were no sta-

Time

3 months

6 months

Azithromycin*

(n 48)

Conventional*

(n 48)

Chi-Square

42 (87.50)

40 (83.33)

34 (70.83)

30 (62.50)

4.04

5.28

*Values in parentheses are percentages.

P .045.

P .022.

tistically significant differences between the trachoma cure rates of tetracycline eye ointment-, oral

doxycycline-, and oral sulfamethoxypyridazinetreated groups. Dawson et al17 reported that 16

doses of azithromycin were equivalent to 30 days of

topical oxytetracycline/polymyxin ointment and may

offer an effective alternative means of controlling

endemic trachoma. Tabbara et al18 reported that single-dose azithromycin is as effective as a 6-week

course of topical tetracycline ointment in the treatment of active trachoma. These findings, when implemented, may help establish high compliance in

treating trachoma and could contribute to the control of trachoma.

Bailey et al19 reported that there were no significant differences in treatment effect, baseline

characteristics, and re-emergent disease between tetracycline eye ointment and single oral dose azithromycin.

Malaty et al20 suggested that there may be an extraocular reservoir of Chlamydia trachomatis infection in trachoma-endemic communities, for example,

in the gut or nasopharynx of infected children, which

may contribute to ocular infection. Systemic therapy,

such as oral azithromycin, would be more likely to

eradicate such a reservoir than would topical tetracycline.

Our finding of a significant difference between

azithromycin and conventional treatment indicates

that the two treatments have unequal efficacy.

In our study, reinfection rates were different for

azithromycin and conventional treatment. The high

rates of reinfection probably reflect the treatment

strategy we adopted, the treatment of only active

cases. It has been shown that subclinically infected

individuals are an important source of reinfection in

a rural area. Mass treatment of the whole community, which would be feasible with single-dose

azithromycin could reduce the rate of reinfection

through elimination of the reservoir of infection.

391

M. GUZEY ET AL.

ORAL AZITHROMYCIN VS TOPICAL OXYTETRACYCLINE

Rates of reinfection would then depend largely on

migration patterns into and out of the communities

treated, and on the success of behavioral interventions, such as face washing, which might reduce the

rate of transmission.16,21,22

The high efficacy rate, low incidence of side effects, and shorter treatment duration suggest that

azithromycin at a dosage of 10 mg/kg per day for 3

days is a viable alternative for the treatment of ocular Chlamydia trachomatis infections. The shorter

treatment duration is likely to improve patient compliance. We believe that azithromycin given at this

dosage represents a potential alternative for the

treatment of active trachoma.

References

1. West SK, Munoz B, Turner WM. The epidemiology of trachoma in central Tanzania. Int J Epidemiol 1991;20:108892.

2. Thylefors B. Present challenges in the global prevention of

blindness. Aust N Z J Ophthalmol 1992;20:8994.

3. West SK, Munoz B, Lynch M, Kayongoya A, Mmbaga BBO,

Taylor HR. Risk factors for constant, severe trachoma among

preschool children in Kongwa, Tanzania. Am J Epidemiol

1996;143:738.

4. Salamon SM. Tetracyclines in ophthalmology. Surv Ophthalmol 1985;29:26575.

9.

10.

11.

12.

13.

14.

15.

16.

17.

18.

19.

5. World Health Organization. Strategies for the prevention of

blindness in national programmes: a primary health care approach. Geneva: World Health Organization, 1984.

20.

6. Dolin PJ, Faal H, Johnson GJ. Reduction of trachoma in a

sub-Saharan village in absence of a disease control programme. Lancet 1997;349:15112.

21.

7. McDonald PJ, Pruul H. Phagocyte uptake and transport of

azithromycin. Eur J Clin Microbiol Infect Dis 1991;10:82833.

8. Nahata MC, Koranyi DI, Gadgil SD. Pharmacokinetics of

azithromycin in pediatric patients after oral administration of

22.

multiple doses of suspension. Antimicrob Agents Chemother

1993;37:3146.

Taylor KI, Taylor HR. Distribution of azithromycin for the

treatment of trachoma. Br J Ophthalmol 1999;83:1345.

Thylefors B, Dawson CR, Jones BR. A simplified system for

the assessment of trachoma and its complications. Bull World

Health Organ 1987;65:47783.

West SK, Rapoza P, Munoz B, Katala S, Taylor HR. Epidemiology of ocular chlamydial infection in a trachomahyperendemic area. J Infect Dis 1991;163:7526.

Guraksin A, Gullulu G. Prevalence of trachoma in eastern

Turkey. Int J Epidemiol 1997;26:43642.

Negrel AD, Minassian DC, Sayek F. Blindness and low vision

in southeast Turkey. Ophthalmic Epidemiol 1996;3:12734.

Jones RB. New treatment for Chlamydia trachomatis. Am J

Obstet Gynecol 1991;164:178993.

Ballow CH, Amsden GW. Azithromycin. The first azalide antibiotic. Ann Pharmacother 1992;26:125361.

Chumbley LC, Viswalingam ND, Thomson IM, Zeidan MA.

Treatment of trachoma in the West Bank. Eye 1988;2:4715.

Dawson CR, Schachter J, Sallam S, Sheta A, Rubinstein RA,

Washton H. A comparison of oral azithromycin with topical

oxytetracycline/polymyxin for the treatment of trachoma in

children. Clin Infect Dis 1997;24:3638.

Tabbara KF, Abu-el-Asrar A, al-Omar O, Choudhury AH,

al-Faisal Z. Single dose azithromycin in the treatment of trachoma. A randomized, controlled study. Ophthalmology

1996;103:8426.

Bailey RL, Arullendran P, Whittle HC, Mabey DCW. Randomized controlled trial of single-dose azithromycin in treatment of trachoma. Lancet 1993;342:4536.

Malaty R, Zaki S, Said ME, Vastine DW, Dawson CR,

Schachter J. Extraocular infections in children in endemic trachoma. J Infect Dis 1981;143:8537.

Ward M, Bailey R, Lesley A, Kajbaf M, Robertson J, Mabey

D. Persisting inapparent chlamydial infection in a trachoma

endemic community in The Gambia. Scand J Infect Dis

1990;69(Suppl):13748.

Taylor HR, West SK, Mmbaga BBO. Hygiene factors and increased risk of trachoma in central Tanzania. Arch Ophthalmol 1989;107:18215.

You might also like

- Cycloplegic Refraction in Optometric Practice 1337594763401 2No ratings yetCycloplegic Refraction in Optometric Practice 1337594763401 214 pages

- (DR Schuster, Nykolyn) Communication For Nurses H (BookFi)100% (1)(DR Schuster, Nykolyn) Communication For Nurses H (BookFi)215 pages

- Pharmacoepidemiology, Pharmacoeconomics,PharmacovigilanceFrom EverandPharmacoepidemiology, Pharmacoeconomics,Pharmacovigilance3/5 (1)

- Herbalist Course Program Info and SyllabusNo ratings yetHerbalist Course Program Info and Syllabus5 pages

- Abpsych Barlow Reviewer 1 Abpsych Barlow Reviewer 1100% (1)Abpsych Barlow Reviewer 1 Abpsych Barlow Reviewer 130 pages

- Severe Fungal Keratitis Treated With Subconjunctival FluconazoleNo ratings yetSevere Fungal Keratitis Treated With Subconjunctival Fluconazole7 pages

- Efficacy and Toxicity of Intravitreous Chemotherapy For Retinoblastoma: Four-Year ExperienceNo ratings yetEfficacy and Toxicity of Intravitreous Chemotherapy For Retinoblastoma: Four-Year Experience8 pages

- A Multicenter, Double Blind Comparison of - MCLINN, SAMUELNo ratings yetA Multicenter, Double Blind Comparison of - MCLINN, SAMUEL15 pages

- Jogi - Basic Ophthalmology, 4th Edition (Ussama Maqbool)No ratings yetJogi - Basic Ophthalmology, 4th Edition (Ussama Maqbool)7 pages

- Comparison Between Topical and Oral Tranexamic Acid in Management of Traumatic HyphemaNo ratings yetComparison Between Topical and Oral Tranexamic Acid in Management of Traumatic Hyphema6 pages

- Clinical Science Efficacy and Safety of Trabeculectomy With Mitomycin C For Childhood Glaucoma: A Study of Results With Long-Term Follow-UpNo ratings yetClinical Science Efficacy and Safety of Trabeculectomy With Mitomycin C For Childhood Glaucoma: A Study of Results With Long-Term Follow-Up6 pages

- Effects of Trans-4 - (Aminomethyl) CyclohexanecarboxylicNo ratings yetEffects of Trans-4 - (Aminomethyl) Cyclohexanecarboxylic15 pages

- Treatment of Acute Otitis Media in Children Under 2 Years of AgeNo ratings yetTreatment of Acute Otitis Media in Children Under 2 Years of Age29 pages

- Amniotic Membrane Transplantation As An Adjunct To Medical Therapy in Acute Ocular BurnsNo ratings yetAmniotic Membrane Transplantation As An Adjunct To Medical Therapy in Acute Ocular Burns8 pages

- Experimental Study On Cryotherapy For Fungal Corneal Ulcer: Researcharticle Open AccessNo ratings yetExperimental Study On Cryotherapy For Fungal Corneal Ulcer: Researcharticle Open Access9 pages

- A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Antimicrobial Treatment For Acute Otitis MediaNo ratings yetA Placebo-Controlled Trial of Antimicrobial Treatment For Acute Otitis Media8 pages

- Three Day Versus Five Day Treatment With AmoxicillNo ratings yetThree Day Versus Five Day Treatment With Amoxicill7 pages

- Jurnal Efficacy and Tolerability of Adjunctive Lacosamide in Pediatric Patients With Focal SeizuresNo ratings yetJurnal Efficacy and Tolerability of Adjunctive Lacosamide in Pediatric Patients With Focal Seizures15 pages

- Evaluation of Umbilical Cord Serum Therapy in Acute Ocular Chemical BurnsNo ratings yetEvaluation of Umbilical Cord Serum Therapy in Acute Ocular Chemical Burns6 pages

- 7.original Article Single Dose Fluconazole in The Treatment of Pityriasis VersicolorNo ratings yet7.original Article Single Dose Fluconazole in The Treatment of Pityriasis Versicolor4 pages

- Milk Oral Immunotherapy Is Effective in School-Aged ChildrenNo ratings yetMilk Oral Immunotherapy Is Effective in School-Aged Children6 pages

- Low-Dose Cyclosporine Treatment For Sight-Threatening Uveitis: Efficacy, Toxicity, and ToleranceNo ratings yetLow-Dose Cyclosporine Treatment For Sight-Threatening Uveitis: Efficacy, Toxicity, and Tolerance8 pages

- A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Antimicrobial Treatment For Acute Otitis MediaNo ratings yetA Placebo-Controlled Trial of Antimicrobial Treatment For Acute Otitis Media6 pages

- Clinical Toleration and Safety of Azithromycin: ChlamydiaNo ratings yetClinical Toleration and Safety of Azithromycin: Chlamydia6 pages

- Effects of Postoperative Cyclosporine OphthalmicNo ratings yetEffects of Postoperative Cyclosporine Ophthalmic7 pages

- Preventing Long-Term Ocular Complications of Trachoma With Topical AzithromycinNo ratings yetPreventing Long-Term Ocular Complications of Trachoma With Topical Azithromycin5 pages

- The Course of Dry Eye After Phacoemulsification Surgery: Researcharticle Open AccessNo ratings yetThe Course of Dry Eye After Phacoemulsification Surgery: Researcharticle Open Access5 pages

- Concise Guide to Clinical Dentistry: Common Prescriptions In Clinical DentistryFrom EverandConcise Guide to Clinical Dentistry: Common Prescriptions In Clinical DentistryNo ratings yet

- NO Nama Barang Pabrik Sisa Satuan: Daftar HargaNo ratings yetNO Nama Barang Pabrik Sisa Satuan: Daftar Harga33 pages

- Assessment of Metabolic and Gastrointestinal, Liver AlterationsNo ratings yetAssessment of Metabolic and Gastrointestinal, Liver Alterations10 pages

- The Healing Power of Chinese Herbs and Medicinal Recipes92% (12)The Healing Power of Chinese Herbs and Medicinal Recipes847 pages

- Abdominal "Signs" Table: Sign Diagnosis/ConditionNo ratings yetAbdominal "Signs" Table: Sign Diagnosis/Condition1 page

- Rehabilitation Protocol For ACL Reconstruction Using Double-Looped Hamstring Graft or Donor Allograft Tendon GraftNo ratings yetRehabilitation Protocol For ACL Reconstruction Using Double-Looped Hamstring Graft or Donor Allograft Tendon Graft4 pages

- Drug Study Drug Name Mechanism of Action Dosage Indication Contraindication Side Effects Nursing InterventionsNo ratings yetDrug Study Drug Name Mechanism of Action Dosage Indication Contraindication Side Effects Nursing Interventions5 pages

- Lab Value Skeletons: Ca MG Phos Na CL BUN K Hco3 Cre GluNo ratings yetLab Value Skeletons: Ca MG Phos Na CL BUN K Hco3 Cre Glu1 page

- Cycloplegic Refraction in Optometric Practice 1337594763401 2Cycloplegic Refraction in Optometric Practice 1337594763401 2

- (DR Schuster, Nykolyn) Communication For Nurses H (BookFi)(DR Schuster, Nykolyn) Communication For Nurses H (BookFi)

- Pharmacoepidemiology, Pharmacoeconomics,PharmacovigilanceFrom EverandPharmacoepidemiology, Pharmacoeconomics,Pharmacovigilance

- Abpsych Barlow Reviewer 1 Abpsych Barlow Reviewer 1Abpsych Barlow Reviewer 1 Abpsych Barlow Reviewer 1

- Severe Fungal Keratitis Treated With Subconjunctival FluconazoleSevere Fungal Keratitis Treated With Subconjunctival Fluconazole

- Efficacy and Toxicity of Intravitreous Chemotherapy For Retinoblastoma: Four-Year ExperienceEfficacy and Toxicity of Intravitreous Chemotherapy For Retinoblastoma: Four-Year Experience

- A Multicenter, Double Blind Comparison of - MCLINN, SAMUELA Multicenter, Double Blind Comparison of - MCLINN, SAMUEL

- Jogi - Basic Ophthalmology, 4th Edition (Ussama Maqbool)Jogi - Basic Ophthalmology, 4th Edition (Ussama Maqbool)

- Comparison Between Topical and Oral Tranexamic Acid in Management of Traumatic HyphemaComparison Between Topical and Oral Tranexamic Acid in Management of Traumatic Hyphema

- Clinical Science Efficacy and Safety of Trabeculectomy With Mitomycin C For Childhood Glaucoma: A Study of Results With Long-Term Follow-UpClinical Science Efficacy and Safety of Trabeculectomy With Mitomycin C For Childhood Glaucoma: A Study of Results With Long-Term Follow-Up

- Effects of Trans-4 - (Aminomethyl) CyclohexanecarboxylicEffects of Trans-4 - (Aminomethyl) Cyclohexanecarboxylic

- Treatment of Acute Otitis Media in Children Under 2 Years of AgeTreatment of Acute Otitis Media in Children Under 2 Years of Age

- Amniotic Membrane Transplantation As An Adjunct To Medical Therapy in Acute Ocular BurnsAmniotic Membrane Transplantation As An Adjunct To Medical Therapy in Acute Ocular Burns

- Experimental Study On Cryotherapy For Fungal Corneal Ulcer: Researcharticle Open AccessExperimental Study On Cryotherapy For Fungal Corneal Ulcer: Researcharticle Open Access

- A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Antimicrobial Treatment For Acute Otitis MediaA Placebo-Controlled Trial of Antimicrobial Treatment For Acute Otitis Media

- Three Day Versus Five Day Treatment With AmoxicillThree Day Versus Five Day Treatment With Amoxicill

- Jurnal Efficacy and Tolerability of Adjunctive Lacosamide in Pediatric Patients With Focal SeizuresJurnal Efficacy and Tolerability of Adjunctive Lacosamide in Pediatric Patients With Focal Seizures

- Evaluation of Umbilical Cord Serum Therapy in Acute Ocular Chemical BurnsEvaluation of Umbilical Cord Serum Therapy in Acute Ocular Chemical Burns

- 7.original Article Single Dose Fluconazole in The Treatment of Pityriasis Versicolor7.original Article Single Dose Fluconazole in The Treatment of Pityriasis Versicolor

- Milk Oral Immunotherapy Is Effective in School-Aged ChildrenMilk Oral Immunotherapy Is Effective in School-Aged Children

- Low-Dose Cyclosporine Treatment For Sight-Threatening Uveitis: Efficacy, Toxicity, and ToleranceLow-Dose Cyclosporine Treatment For Sight-Threatening Uveitis: Efficacy, Toxicity, and Tolerance

- A Placebo-Controlled Trial of Antimicrobial Treatment For Acute Otitis MediaA Placebo-Controlled Trial of Antimicrobial Treatment For Acute Otitis Media

- Clinical Toleration and Safety of Azithromycin: ChlamydiaClinical Toleration and Safety of Azithromycin: Chlamydia

- Preventing Long-Term Ocular Complications of Trachoma With Topical AzithromycinPreventing Long-Term Ocular Complications of Trachoma With Topical Azithromycin

- The Course of Dry Eye After Phacoemulsification Surgery: Researcharticle Open AccessThe Course of Dry Eye After Phacoemulsification Surgery: Researcharticle Open Access

- Concise Guide to Clinical Dentistry: Common Prescriptions In Clinical DentistryFrom EverandConcise Guide to Clinical Dentistry: Common Prescriptions In Clinical Dentistry

- Assessment of Metabolic and Gastrointestinal, Liver AlterationsAssessment of Metabolic and Gastrointestinal, Liver Alterations

- The Healing Power of Chinese Herbs and Medicinal RecipesThe Healing Power of Chinese Herbs and Medicinal Recipes

- Rehabilitation Protocol For ACL Reconstruction Using Double-Looped Hamstring Graft or Donor Allograft Tendon GraftRehabilitation Protocol For ACL Reconstruction Using Double-Looped Hamstring Graft or Donor Allograft Tendon Graft

- Drug Study Drug Name Mechanism of Action Dosage Indication Contraindication Side Effects Nursing InterventionsDrug Study Drug Name Mechanism of Action Dosage Indication Contraindication Side Effects Nursing Interventions

- Lab Value Skeletons: Ca MG Phos Na CL BUN K Hco3 Cre GluLab Value Skeletons: Ca MG Phos Na CL BUN K Hco3 Cre Glu