Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of A Survey On Forty Propositions

Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of A Survey On Forty Propositions

Uploaded by

Armando MartinsCopyright:

Available Formats

Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of A Survey On Forty Propositions

Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of A Survey On Forty Propositions

Uploaded by

Armando MartinsOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of A Survey On Forty Propositions

Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of A Survey On Forty Propositions

Uploaded by

Armando MartinsCopyright:

Available Formats

Economic History Association

Where Is There Consensus Among American Economic Historians? The Results of a Survey on

Forty Propositions

Author(s): Robert Whaples

Source: The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 55, No. 1 (Mar., 1995), pp. 139-154

Published by: Cambridge University Press on behalf of the Economic History Association

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2123771

Accessed: 26/01/2009 17:26

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use, available at

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp. JSTOR's Terms and Conditions of Use provides, in part, that unless

you have obtained prior permission, you may not download an entire issue of a journal or multiple copies of articles, and you

may use content in the JSTOR archive only for your personal, non-commercial use.

Please contact the publisher regarding any further use of this work. Publisher contact information may be obtained at

http://www.jstor.org/action/showPublisher?publisherCode=cup.

Each copy of any part of a JSTOR transmission must contain the same copyright notice that appears on the screen or printed

page of such transmission.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit organization founded in 1995 to build trusted digital archives for scholarship. We work with the

scholarly community to preserve their work and the materials they rely upon, and to build a common research platform that

promotes the discovery and use of these resources. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Economic History Association and Cambridge University Press are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize,

preserve and extend access to The Journal of Economic History.

http://www.jstor.org

Where Is There Consensus Among

American Economic Historians?

The Results of a Survey on Forty

Propositions

ROBERTWHAPLES

This article examines where consensus does and does not exist among American

economic historians by analyzing the results of a questionnaire mailed to 178

randomly selected members of the Economic History Association. The questions

address many of the important debates in American economic history. The

answers show consensus on a number of issues, but substantial disagreement in

many areas-including the causes of the Great Depression and the aftermath of

emancipation. They also expose some areas of disagreement between historians

and economists.

Is

there a consensus among American economic historians on the

critical issues at the heart of the discipline? Although assertions of

consensus are frequently made, they are usually only conjectures. We

do not systematically observe the final product of the intellectual

production process-the beliefs held by the large, often silent, body of

scholars after the evidence in support of competing views has been

weighed. This article disturbs the silence. It examines where consensus

does and does not exist among American economic historians by

analyzing the results of a questionnaire mailed to 178 randomly selected

members of the Economic History Association (see the Appendix).

The results of the survey can help guide the research agenda of

economic historians. Some scholars will find that their beliefs run

against the prevailing consensus. They may wish to re-evaluate their

positions or redouble their efforts to convince colleagues by restating

their case or pursuing additional research.

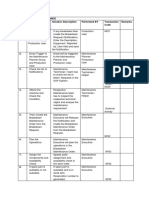

Table 1 contains the questionnaire and compares the responses of

economists and historians, performing Chi-square and t-tests for differences in responses between the two groups. The questions address

many of the important debates in American economic history. The

answers show consensus on a number of the issues, but substantial

disagreement in many areas.' They also expose areas of disagreement

The Journal of Economic History, Vol. 55, No. 1 (Mar. 1995). ?The Economic History

Association. All rightsreserved. ISSN 0022-0507.

Robert Whaples, Departmentof Economics, Wake Forest University, Winston-Salem,NC

27109. Whaples@wfu.edu.

For commentsand advice I thankDavid Mitch, Lee Craig,the participantsat the Social Science

History Association meetings, Atlanta, October 1994, and members of the Econhist.Teach

electronicnetwork.

tIn discussingthe results, the followingrulesof thumbwill be employed.If two-thirdsor more

139

Whaples

140

TABLE I

RESPONSES TO QUESTIONNAIRE ON AMERICAN ECONOMIC HISTORY

The top row of numbers next to each question gives the percentage distribution of responses by

economists. The second row gives the percentage distribution of responses by historians.

E= economists

H= historians

A = generally agree

P = agree-but with provisos

D = generally disagree

Pr = confidence level with which one can reject the equality of the distribution of the two

groups' answers, using the Likelihood Ratio Chi-square statistic, followed by the confidence

level with which one can reject the equality of the percent who disagree with the proposition,

using a pooled variance t-test.

% = percent of economists who answered the question, followed by percent of historians who

answered.

(A second appendix gives sources and explanations for the propositions. It is available from the

author.)

COLONIAL ECONOMY

E

H

Pr

%

A

83

81

22/36

91/95

P

12

16

D

5

3

1. The economic standard of living of white Americans on the

eve of the Revolution was among the highest in the world.

E

H

Pr

%

A

82

67

74/65

98/100

P

11

21

D

7

13

2. Indentured servitude was an institutional response to a capital

market imperfection. It enabled prospective migrants to borrow

against their future earnings in order to pay the high cost of

passage to America.

E

H

Pr

%

A

6

9

57/63

78/90

P

33

20

D

61

71

3. Eighteenth-century rural farmers in the North were isolated

from the market.

ECONOMIC CAUSES OF THE REVOLUTION AND CONSTITUTION MAKING

E

H

Pr

%

A

0

12

97/95

78/87

P

8

15

D

92

74

4. The debts owed by colonists to British merchants and other

private citizens constituted one of the most powerful causes

leading to the Revolution.

E

H

Pr

%

A

10

12

62/73

63/67

P

31

15

D

59

73

5. One of the primary causes of the American Revolution was

the behavior of British and Scottish merchants in the 1760s and

1770s, which threatened the abilities of American merchants to

engage in new or even traditional economic pursuits.

E

H

Pr

%

A

60

65

11/12

91/95

P

29

24

D

12

11

6. The costs imposed on the colonists by the trade restrictions

of the Navigation Acts were small.

E

H

Pr

%

A

21

13

35/30

94/97

P

26

29

D

53

58

7. The economic burden of British policies was the spark to the

American Revolution.

Consensus Among American Economic Historians?

TABLE

E

H

Pr

%

A

27

25

91/95

80/92

P

43

22

D

30

53

141

1-continued

8. The personal economic interests of delegates to the

Constitutional Convention generally had a significant effect on

their voting behavior.

ANTEBELLUM PERIOD

E

H

Pr

%

A

36

56

83/85

91/93

P

33

28

D

31

17

9. During the early national and antebellum period, export trade,

particularly in cotton, was of prime importance as a stimulant to

the economy.

E

H

Pr

%

A

49

34

96/98

89/90

P

44

37

D

7

29

10. Antebellum tariffs harmed the southern states and benefited

the Northern states.

E

H

Pr

%

A

16

3

84/83

80/82

P

14

13

D

70

84

11. Nineteenth-century U.S. land policy, which attempted to

give away free land, probably represented a net drain on the

productive capacity of the country.

E

H

Pr

%

A

17

23

58/48

76/77

P

34

20

D

49

57

12. The lower female-to-male earnings ratio in the Northeast

was one of the reasons it industrialized before the South.

E

H

Pr

%

A

30

9

94/92

72/85

P

36

36

D

33

55

13. Before 1833, the U.S. cotton textile industry was almost

entirely dependent on the protection of the tariff.

SLAVERY

E

H

Pr

%

A

2

3

20/46

100/100

A

0

3

54/52

98/92

A

48

30

67/49

100/95

E

H

Pr

%

A

23

22

75/85

94/92

E

H

Pr

%

E

H

Pr

%

P

4

8

D

93

90

14. Slavery was a system irrationally kept in existence by

plantation owners who failed to perceive or were indifferent to

their best economic interests.

P

2

3

D

98

95

15. The slave system was economically moribund on the eve of

the Civil War.

P

24

35

D

28

35

16. Slave agriculture was efficient compared with free

agriculture. Economies of scale, effective management, and

intensive utilization of labor and capital made southern slave

agriculture considerably more efficient than nonslave southern

farming.

P

35

19

D

42

58

17. The material (rather than psychological) conditions of the

lives of slaves compared favorably with those of free industrial

workers in the decades before the Civil War.

Whaples

142

TABLE

1- continued

POPULISM

18. The agrarian protest movement in the Middle West from

1870 to 1900 was a reaction to the commercialization of

agriculture.

E

H

Pr

%

A

30

38

33/2

96/95

P

41

32

D

30

30

E

H

Pr

%

A

19

49

99/99

94/95

P

47

46

D

35

5

19. The agrarian protest movement in the Middle West from

1870 to 1900 was a reaction to movements in prices.

E

H

Pr

A

22

34

92/97

P

24

37

D

54

29

20. The agrarian protest movement in the Middle West from

1870 to 1900 was a reaction to the deteriorating economic status

of farmers.

89/97

SOUTHERN ECONOMY SINCE THE CIVIL WAR

D

21. The monopoly power of the merchant in the postbellum rural

cotton South was used to exploit many farmers and to force

49

21

them into excessive production of cotton by refusing credit to

those who sought to diversify production.

E

H

Pr

%

A

27

36

96/98

89/85

P

24

42

E

H

Pr

%

A

26

31

65/82

91/82

P

14

25

D

60

44

22. The crop mix chosen by most farmers in the postbellum

cotton South was economically inefficient and therefore southern

agriculture was less productive than it might have been.

E

H

Pr

A

26

47

83/89

P

21

20

D

52

33

23. The system of sharecropping impeded economic growth in

the postbellum South.

91/77

E

H

Pr

%

A

47

27

85/91

83/85

P

26

27

D

26

46

24. American blacks achieved substantial economic gains during

the half-century after 1865.

E

H

Pr

%

A

26

0

99/99

76/69

P

40

22

D

34

78

25. In the postbellum South economic competition among whites

played an important part in protecting blacks from racial

coercion.

E

H

Pr

%

A

38

50

45/64

80/78

P

24

23

D

38

27

26. The modern period of the South's economic convergence to

the level of the North only began in earnest when the

institutional foundations of the southern regional labor market

were undermined, largely by federal farm and labor legislation

dating from the 1930s.

BANKING AND CAPITAL MARKETS

E

H

Pr

%

A

72

69

83/85

85/82

P

15

28

D

13

3

27. The inflation and financial crisis of the 1830s had their origin

in events largely beyond President Jackson's control and would

have taken place whether or not he had acted as he did vis-a-vis

the Second Bank of the U.S.

Consensus Among American Economic Historians?

TABLE

143

1-continued

E

H

Pr

%

A

0

17

99/99

87/7

P

2

17

D

98

67

28. "Free banking" during the antebellum era hurt the

economy.

E

H

Pr

%

A

12

12

5/22

89/85

P

24

21

D

63

67

29. During the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, the

Gold Standard was effective in stabilizing prices and moderating

business-cycle fluctuations.

A

9

13

99/99

98/97

P

2

21

D

89

66

30. Without the building of railroads, the American economy

would have grown very little during the nineteenth century.

RAILROADS

E

H

Pr

%

LABOR MARKETS

E

H

Pr

%

A

26

66

99/58

83/93

P

53

19

D

21

14

31. The increased participation of American women over the

long run has resulted more from economic developments, such

as the decrease in hours of work, the rise of white-collar work,

and increased real wages, than from shifts in social norms and

attitudes.

E

H

Pr

%

A

54

63

36/7

85/82

P

28

19

D

18

19

32. The reduction in the length of the workweek in American

manufacturing before the Great Depression was primarily due to

economic growth and the increased wages it brought.

E

H

Pr

%

A

5

6

29/58

89/87

P

24

32

D

71

62

33. The reduction in the length of the workweek in American

manufacturing before the Great Depression was primarily due to

the efforts of labor unions.

GREAT DEPRESSION AND BUSINESS CYCLES

E

H

Pr

%

A

14

17

74/75

91/90

P

33

17

D

52

66

34. Monetary forces were the primary cause of the Great

Depression.

E

H

Pr

%

A

48

46

46/50

54/67

P

12

23

D

40

31

35. The demand for money was falling more rapidly than the

supply of money during 1930 and the first three-quarters of 1931.

E

H

Pr

%

A

32

31

7/24

96/82

P

43

47

D

25

22

36. Throughout the contractionary period of the Great

Depression, the Federal Reserve had ample powers to cut short

the process of monetary deflation and banking collapse. Proper

action would have eased the severity of the contraction and very

likely would have brought it to an end at a much earlier date.

E

H

Pr

%

A

18

23

55/59

85/79

P

44

29

D

39

49

37. A fall in autonomous spending, particularly investment, is

the primary explanation for the onset of the Great Depression.

Whaples

144

TABLE

1-continued

E

H

Pr

%

A

60

64

11/12

94/85

P

26

21

D

14

15

38. The passage of the Smoot-Hawley Tariff exacerbated the

Great Depression.

E

H

Pr

%

A

27

6

97/95

89/87

P

22

21

D

51

74

39. Taken as a whole, government policies of the New Deal

served to lengthen and deepen the Great Depression.

E

H

Pr

%

A

54

73

95/97

89/77

P

24

23

D

22

3

40. The cyclical volatility of GNP and unemployment was

greater before the Great Depression than it has been since the

end of World War Two.

between EHA members in history departmentsand members in economics departments.

COLONIAL

ECONOMY

Three disparatequestions deal with the colonial economy. There is an

overwhelmingconsensus that Americans' economic standardof living

on the eve of the Revolution was among the highest in the world.

Likewise, a vast majorityaccept the view that indenturedservitudewas

an economic arrangementdesigned to iron out imperfections in the

capital market. Neither of the statements has generatedheated discussion recently in light of the well-known works by Alice Hanson Jones

and David Galenson.2

The third colonial era topic has been the subject of much argument.

New Left historians,such as James Henretta,have laid out the case that

many eighteenth-centuryfarmersin the northerncolonies were "isolated" fromthe market.WinifredRothenberghas spent considerableeffort

attemptingto refute this idea and seems to have succeeded.361 percent

of economists and 71 percent of historiansin the sample disagree with

the characterizationof these farmers as "isolated from the market."

Among those who agree, only a handful do so wholeheartedly-most

would add provisos to the statement.

of the respondents disagree with a proposition, this will be called a "consensus" against the

statement. If one-third or less disagree, this will be referred to as a "consensus" in favor of the

proposition.

2 Jones, Wealth; and Galenson, "Rise and Fall."

I Henretta, "Families and Farms"; and Rothenberg, "Market."

Consensus Among American Economic Historians?

145

ECONOMIC CAUSES OF THE REVOLUTION AND CONSTITUTION MAKING

Four of the questions deal with the causes of the American Revolution. There is a consensus on some of the narrowerpropositions: that

debts owed by colonists and the practices of Britishmerchantswere not

primarycauses of the revolution; and that the costs of the Navigation

Acts' trade restrictions were small.4 Nonetheless, almost half of the

economic historians believe that the economic burden of the British

policies was "the spark" to the AmericanRevolution.s Most who favor

this position, however, do so with provisos. The bottom line is that

there is no consensus on whetheror not the economic burdensof British

policies sparked the colonists' bid for independence.

At the beginningof the century, CharlesBeardlaid out the case for an

economic interpretationof the makingof the U.S. Constitution.Among

other things, he arguedthat the personal economic interests of delegates

to the ConstitutionalConventionhad a significanteffect on their actions

in writing the Constitution.6 Although historians are divided on the

question, the consensus among economists in the EHA is that this

proposition is correct. (Of course, this does not necessarily imply an

agreement with Beard's more particularclaims about which personal

interests matteredand how they mattered.)

ANTEBELLUM PERIOD

Consensus exists on the two propositions concerning antebellum

trade. Most agree with Douglass North's position that duringthe early

nationaland antebellumperiod, export trade, particularlyin cotton, was

of prime importance as a stimulantto the economy.7 Likewise, most

agree that antebellumtariffs harmedthe southern states and benefited

the northern states.8 In both cases, however, a considerable number

would add provisos to these statements.

There is substantial disagreement with the proposition that nineteenth-centuryU.S. land policy probablyrepresenteda net drainon the

productivecapacity of the country. TerryAnderson and Peter Hill have

recently restated this proposition,pointingout that the opportunitycost

of squatting(queuing)is high because it removes productive resources

from their most valuableuse.9 Evidently, those surveyed do not buy (or

are unaware of) this logic.

There is divided opinion on the two questions concerning industrial4 See McCusker and Menard, Economy, p. 354; Beard, Economic Origins, p. 270; and Egnal and

Ernst, "Economic Interpretation."

5 This wording is based on Reid, "Economic Burden?"

6 See Beard, Economic Interpretation; and McGuire and Ohsfeldt, "Economic Model."

7 North, Economic Growth.

8 For a good discussion, see Atack and Passell, New Economic View, p. 139.

' Anderson and Hill, "Are Government Giveaways?"

146

Whaples

ization. Roughly half those surveyed agree with the proposition put

forth by Claudia Goldin and Kenneth Sokoloff that the lower femaleto-male earnings ratio in the Northeast was one of the reasons it

industrializedbefore the South.10 The other half disagree. There is also

a split on the proposition that before 1833, the U.S. cotton textile

industry was almost entirely dependent on the protection of the tariff.

More than half the historiansdisagree, whereas the economists tend to

accept the recent quantitativeargumentsof MarkBils and Knick Harley

that an unprotected American cotton textile industry could not have

competed."

SLAVERY

Perhapsthe most exciting time in the historyof the professionwas the

period in which the issue of slavery dominatedthe agenda. Publication

of Robert Fogel and Stanley Engerman'sTime on the Cross generated

a cottage industry of refutationsand rebuttals.12Now that most of the

dust has settled, whose argumentshave won the day?

The survey's four propositions about slavery come straight out of

Time on the Cross.13 Two of them prove to be noncontroversialand

were probably already widely accepted when Fogel and Engerman

restated them. There is near unanimitythat slavery was not a system

irrationallykept in existence by plantationowners and that the slave

system was not economically moribundon the eve of the Civil War.

One of the most contested issues in the debate has been Fogel and

Engerman's proposition that slave agriculturewas efficient compared

with free agriculture.Economies of scale, effective management, and

intensive utilizationof labor and capitalmade southernslave agriculture

considerablymore efficientthan nonslave southernfarming.Apparently

Fogel, Engerman, and others have convinced most of the profession

that this proposition is correct. Almost half the economists generally

agree with the idea, another quarteragree if provisos are added to the

statement. Historiansare almost as supportiveof the proposition. Only

28 percent of the economists and 35 percent of the historiansgenerally

disagree with the assertionthat slave agriculturewas efficientcompared

with free agriculture.

On the last slavery question, opinion is sharply divided. More than

half of the historians and almost half of the economists disagree with

Fogel and Engerman'spropositionthat the material(not psychological)

conditions of the lives of slaves comparedfavorablywith those of free

0 Goldin and Sokoloff, "Relative Productivity Hypothesis."

11 See Bils, "Tariff Protection"; and Harley, "International Competitiveness."

12 See Fogel and Engerman, Time and "Explaining"; and David et al., Reckoning.

13 Fogel and Engerman, Time, pp. 4-5.

Consensus Among American Economic Historians?

147

industrialworkers in the decades before the Civl War. Among the half

that concur with the statement, most do so with some reservations.

POPULISM

Three of the survey's questions consider the "puzzle" of Midwestern

agrarian discontent in the late 1800s. The three "explanations" of

populist protest are not mutuallyexclusive. First, there is a consensus

in supportof Anne Mayhew's propositionthat the protest was a reaction

to the commercialization of agriculture.14 However, most support

Mayhew's propositiononly if some provisos are added. A near consensus holds that the protest was a reaction to "movements in prices."'15

On this question economists are much more likely to dissent than

historians. Finally, there is considerable disagreement over the third

proposition, which blames the protest on "the deterioratingeconomic

status of farmers." A slight majorityof the economists disagreewith the

idea, probably citing quantitative evidence on relative prices and

absolute incomes. 16 However, many, especially the bulk of the historians, agree with the proposition that "deterioratingeconomic status"

inflamedagrariandiscontent.

SOUTHERN ECONOMY SINCE THE CIVIL WAR

As the debate over slavery cooled down, disagreement about the

aftermath of emancipation intensified. Occupying center stage in this

second debate was Roger Ransom and Richard Sutch's One Kind of

Freedom. Three of their propositions are addressed in the survey. On

none of the three do economists and historians see eye to eye.

Historians are much more likely to embrace the positions of Ransom

and Sutch.

Economists are almost evenly divided on the proposition that the

monopoly power of the merchantin the postbellum ruralcotton South

was used to exploit many farmers and to force them into excessive

productionof cotton by refusingcredit to those who sought to diversify

production.17 The vast majority of historians support this position.

Three out of five economists reject the argument that the crop mix

chosen by most farmers in the postbellum cotton South was economically inefficientand therefore southern agriculturewas less productive

than it might have been. 18 Yet, a little over half of the historiansaccept

the argument.Finally, a slim majorityof economists reject the suggestion that the system of sharecroppingimpeded economic growth in the

14

Mayhew, "A Reappraisal."

5 See, for example, McGuire, "Economic Causes."

16 See for example, North, Growth; and Atack and Passell, New Economic View, pp. 419-24.

17 Ransom and Sutch, One Kind, p. 149.

18

Ibid., p. 169.

148

Whaples

postbellum South.19However, only one-third of historians reject the

proposition. Thus, on the issues of monopoly merchant power, crop

mix, and sharecroppingthere is no consensus among EHA members

and considerable differences among economists and historians.

On two of the other questions about post-Civil War southern economic history there are also divisions between historians and economists. The consensus opinion among the economists is that "American

blacks achieved substantialeconomic gains duringthe half century after

1865.",20 Nearly half of the historiansdo not concur with this interpretation. Differingstandardsof "substantial"may be at the center of this

disagreement.Robert Higgs's propositionthat in the postbellum South

economic competition among.whites played an importantpart in protecting blacks from racial coercion yields the most dramaticdifference

of opinion found in the survey.21 Economists and historians have

reached the opposite conclusions. Two-thirdsof the economists support

Higgs's statement, only 22 percent of historians do. These responses

highlighta recurringdifferencedividinghistoriansand economists. The

economists have more faith in the power of the competitive market. For

example, they see the competitive marketas protectingdisenfranchised

blacks and are less likely to accept the idea that there was exploitation

by merchantmonopolists.

The final question on the southern economy tests Gavin Wright's

argumentthat the modernperiod of the South's economic convergence

to the level of the North only began in earnest when the institutional

foundations of the southern regional labor market were undermined,

largely by federal farm and labor legislation dating from the 1930s.22

Most of the respondents accept Wright'sposition.

MONEY AND BANKING

Economic historianshave reached a consensus on all of the survey's

questions regardingmoney and banking. The vast majorityagree with

Peter Temin's conclusion that the inflation and financial crisis of the

1830s had their origin in events largely beyond President Jackson's

control and would have taken place whether or not he had acted as he

did vis-a-vis the Second Bank of the U.S.23

19Ibid., p. 103.

Higgs, Competition, p. ix; and Margo, "Accumulation."

Higgs, Competition, p. ix.

22 Wright, "Economic Revolution," p. 162.

23 Temin, Jacksonian Economy, back cover. This finding contrasts with the results of a survey

conducted by David Whitten (Whitten, "Depression"). Whitten sent questionnaires to 800

historians and economic historians, compiling an address list from the membership of the EHA, the

Business History Conference, the Cliometric Society, and the Economic and Business Historical

Society. He asked several questions about how the events surrounding the depression of 1837 are

presented in the classroom. Among the questions and responses were these:

20

21

Consensus Among American Economic Historians?

149

The economists are nearly unanimousin their rejection of the idea

that "free banking" (free entry into the bankingbusiness, ratherthan

freedom to conduct business without regulation)harmedthe economy

duringthe antebellumera.24Althoughmost historianshave reached the

same conclusion, as many as one-thirdaccept the propositionthat free

banking hurt the economy. This difference is another indication that

economists have greater confidence in the power of a competitive

market.

Finally, about two-thirdsof both groups reject the idea that the Gold

Standardwas effective in stabilizing prices and moderatingbusinesscycle fluctuationsduringthe nineteenthcentury.25

RAILROADS

Before he turnedto slavery, Fogel's estimates of the social savings of

the railroads ignited a fervent debate.26 The survey indicates that

Fogel's ideas have carriedthe day in this dispute. Almost 90 percent of

economists and two-thirds of historians now reject the "axiom of

indispensability."

LABOR MARKETS

Goldin has argued that the increased labor force participationof

American women over the long run has resulted more from economic

developments, such as the decrease in hours of work, the rise of

QUESTION 5: "I present the Temin analysis as the explanation of the U.S. economic

collapse of 1837. I reject, with Temin, what he terms the classical explanation."

Economists, 21 yes, 20 no; Historians, 4 yes, 12 no.

QUESTION 6: "I present the Temin analysis, but reject it as the explanation of the U.S.

economic collapse of 1837, accepting, instead, what Temin terms the classical explanation."

Economists, I yes, 36 no; Historians, 3 yes, 13 no.

QUESTION 8: "I discuss the U.S. economic collapse of 1837 in terms of what Temin calls

the classical explanation and Temin's innovations, synthesizing the two approaches for my

students."

Economists, 29 yes, 12 no; Historians, 12 yes, 5 no.

The responses to Whitten's questionnaire show much less of a consensus in favor of Temin's

position than do the responses to this survey. (However, they show a clear consensus in rejecting

the "classical" explanation.) Although Whitten finds that the majority of economists teaching

economic history agree with Temin's interpretation, it is a slender majority. One reason may be

that this survey focuses more narrowly than does Whitten's on one component of Temin's thesis.

Another reason could be that the two groups surveyed are not identical. In addition, it is possible

that someone who "synthesizes" the two approaches (Whitten question 8) would answer that they

"agree with provisos" with the statement in question 27 of this survey.

24 See Rockoff, "Free Banking Era."

25

See Eichengreen, "As Good as Gold."

26 Fogel, Railroads and "Notes."

150

Whaples

white-collarwork, and increased real wages than from shifts in social

norms and attitudes.27The vast majorityof those surveyed agree.

Two of the labor marketquestions concern the forces responsiblefor

the decline in the length of the Americanworkweekin the period before

the Great Depression.28The consensus here is that economic growth

and increased wages were mainly responsible. Most economic historians reject a primaryrole for labor unions.

GREAT DEPRESSION AND BUSINESS CYCLES

Four of the questionnaire'spropositionsare taken from Temin's Did

Monetary Forces Cause the Great Depression? and Milton Friedman

and Anna Schwartz's TheGreat Contraction.The answers reveal a lack

of consensus on the causes of the Great Depression.

The first proposition restates the Friedman and Schwartz position

that "monetary forces were the primarycause of the Great Depression. 29 Economists are almost evenly split on this question, whereas

about two-thirdsof the historiansreject the monetaristproposition.

The second question of this section is much narrower. It must be

treated with caution because it has the lowest response rate of the

survey, with two in five of the sample members declining to respond.

Sixty percent of the economists and nearly 70 percent of the historians

agree with Temin that the "demandfor money was fallingmore rapidly

than the supply during 1930 and the first three-quartersof 1931.'30

Althoughthe traditionalKeynesian explanationholds the edge in the

first two questions, there is a consensus among both groups that

"throughout the contractionaryperiod of the Great Depression, the

FederalReserve had amplepowers to cut short the process of monetary

deflation and banking collapse. Proper action would have eased the

severity of the contractionand very likely would have broughtit to an

end at a much earlier date."31 However, most supporters of this

position requirethat unnamedprovisos be added before the contention

is fully accepted.

Finally, economic historiansare sharply divided over the traditional

Keynesian alternative explanation of the depression that a fall in

autonomous spending, particularlyinvestment, is the primaryexplanation for the onset of the Great Depression.32 About 40 percent of

economists and 50 percent of historiansdisagree with the hypothesis:

only about one-fifth accept it without provisos.

Goldin, Understanding, p. 5.

See Whaples, "Winning."

2' Friedman and Schwartz, Great Contraction. This is the proposition tested by Temin in Did

Monetary Forces?

30 Temin, Did Monetary Forces? p. 137.

31 Friedman and Schwartz, Great Contraction, preface.

32

Temin, Did Monetary Forces? back cover.

27

28

Consensus Among American Economic Historians?

151

Do these results indicatea belief amongeconomic historiansthat both

monetarist and Keynesian explanationshave some merit? Or is this a

message of irreconcilabledifferences?Despite considerableinnovative

and painstakingsubsequentresearchabout the causes and natureof the

Great Depression, this may be a debate from which no consensus will

ever emerge.33

Although the central causes of the depression are still hotly contested, there is a consensus that the "passage of the Smoot-Hawley

Tariff exacerbated the Great Depression."34 Vice President Albert

Gore's assertion (in his NAFTA debate with H. Ross Perot) of our

consensus on this issue, has been corroborated.

On top of the profession's lack of agreementabout the genesis of the

Great Depression, there is a disagreementabout the effect of the New

Deal. In fact, the economists in the sampleare almost evenly dividedon

the question of whether or not when taken "as a whole, government

policies of the New Deal served to lengthen and deepen the Great

Depression." The consensus among historiansis that the new Deal did

not lengthen and deepen the depression.

The final debate addressed in the survey concerns the cyclical

volatility of the economy before and after the Great Depression.

ChristinaRomerhas arguedthat earlierstudies overstatedthe pre-Great

Depression volatility of the economy. Her findingsgenerateda flurryof

researchand rethinkingon the issue.35The currentconsensus is that the

volatility of GNP and unemployment were greater before the Great

Depression than they have been since the end of World War II.

CONCLUSIONS

The results of the survey can be very useful in the classroom. The

findingsgo fartherthan textbooks in helping students get a sense of the

collective wisdom of economic historiansand emphasize that economic

history like both its parents, economics and history, is full of unsettled

debates.

The results can also guide the research agenda of economic historians. Some scholars will find that their beliefs run against the prevailing

consensus. This need not meanthat theirbeliefs are incorrect.Each one

of us probablydisagrees with one or more of the consensuses shown in

Table 1. Those holding minority views may wish to re-evaluate their

position or to redouble their efforts to convince their colleagues by

restatingtheir case or pursuingadditionalresearch.

33

34

3S

However, see Romer, "Nation."

See for example, Fearon, War, p. 129.

Romer, "New Estimates." See also, Weir, "Reliability."

152

Whaples

Appendix

THE QUESTIONNAIRE: ORIGINS AND RESPONDENTS

This study is modeled on Alston et al., "Is There a Consensus among Economists in

the 1990s?"

The questionnaire was sent to 90 economists (Ph.D. in economics or currently

teaching in an economics department) and 88 historians (Ph.D. in history or currently

teaching in a history department). Each group was randomly selected from the 1993

Economics History Association Telecommunications Directory, using the following

procedure. The last two economists and the last two historians from each page of the

directory who met the following criteria were selected. (In some cases, particularly

among historians, there were not two who met the criteria. This necessitated selecting

three or more from the next page of the directory.) All individuals selected teach in the

United States, hold a Ph.D., and identify a research interest in the United States or

North America. This information was ascertained from Economic History Association,

"1991 Economic History Association Membership Directory," this JOURNAL, 51,

Supplement 1 (Mar. 1991). Those not reporting the necessary information were

excluded. The EHA had approximately 1,200 members in 1994. Of these, 427 are

teaching in the United States in departments of economics, business, and the like. One

hundred sixty-five are teaching in history departments in the United States.

The population that was sent questionnaires is probably representative of EHA

members. It is hoped that those who returned the survey are also representative. I know

of no reason that they are not. Busier economic historians may be less likely to return

the questionnaires, but I do not believe that their responses would differ systematically

from those obtained. However, it is plausible that the respondents may not be

representative of economic historians who are not EHA members. The questionnaire

guaranteed anonymity, but there was a superficial difference between the questionnaires

of economists and historians, so subdiscipline can be identified for all respondents. A

stamped, addressed return envelope was included and this helped generate a response

rate of 48 percent. 51 percent for economists, 44 percent for historians.

In 1991, the Committee on Education in Economic History organized a syllabus

exchange. These reading lists demonstrate the great variety in what economic historians

teach, but also reflect the core readings economic historians assign to their students.

The questions included in this survey are largely drawn from the readings that

frequently appeared on these syllabi, the "best sellers of American economic history."

Many of these readings have been reprinted in Whaples and Betts, Historical Perspectives on the American Economy.

REFERENCES

Alston, Richard M., J. R. Kearl, and Michael B. Vaughan, "Is There a Consensus

among Economists in the 1990s?" American Economic Review: Papers and

Proceedings, 82 (May 1992), pp. 203-9.

Anderson, Terry, and Peter J. Hill, "Are Government Giveaways Really Free?" in

Donald McCloskey, ed., Second Thoughts: Myths and Morals of U.S. Economic

History (New York, 1993).

Atack, Jeremy, and Peter Passell, A New Economic View of American History from

Colonial Times to 1940 (2nd edn., New York, 1994).

Consensus Among American Economic Historians?

153

Beard, Charles A., Economic Origins of Jeffersonian Democracy (New York, 1915).

Beard, Charles A., An Economic Interpretation of the Constitution of the United States

(2nd edn., New York, 1935).

Bils, Mark, "Tariff Protection and Production irn the Early U.S. Cotton Textile

Industry," this JOURNAL, 44 (Dec. 1984), pp. 1,033-45.

David, Paul, et al., Reckoning With Slavery: A Critical Study in the Quantitative History

of American Negro Slavery (New York, 1976).

Egnal, Mark, and Joseph Ernst, "An Economic Interpretation of the American

Revolution," William and Mary Quarterly, 3rd series 29 (Jan. 1972), pp. 3-32.

Eichengreen, Barry, "As Good as Gold-By What Standard?" in Donald McCloskey,

ed., Second Thoughts: Myths and Morals of U.S. Economic History (New York,

1993).

Fearon, Peter, War, Prosperity and Depression: The U.S. Economy, 1917-1945

(Lawrence, KS, 1987).

Fogel, Robert, Railroads and American Economic Growth: Essays in Econometric

History (Baltimore, 1964).

Fogel, Robert, "Notes on the Social Savings Controversy," this JOURNAL, 39 (Mar.

1979), pp. 1-54.

Fogel, Robert, and Stanley Engerman, Time on the Cross: The Economics of American

Negro Slavery (New York, 1974).

Fogel, Robert, and Stanley Engerman, "Explaining the Relative Efficiency of Slave

Agriculture in the Antebellum South," American Economic Review, 67 (June 1977),

pp. 275-96.

Friedman, Milton, and Anna J. Schwartz, The Great Contraction, 1929-1933 (Princeton, 1965).

Galenson, David, "The Rise and Fall of Indentured Servitude in the Americas: An

Economic Analysis," this JOURNAL, 44 (Mar. 1984), pp. 1-26.

Goldin, Claudia, Understanding the Gender Gap: An Economic History of American

Women (New York, 1990).

Goldin, Claudia, and Kenneth Sokoloff, "The Relative Productivity Hypothesis of

Industrialization: The American Case, 1820 to 1850," Quarterly Journal of Economics, 69 (Aug. 1984), pp. 461-88.

Harley, C. Knick, "International Competitiveness of the Antebellum American Cotton

Textile Industry," this JOURNAL, 52 (Sept. 1992), pp. 559-84.

Henretta, James, "Families and Farms: Mentalite in Pre-Industrial America," William

and Mary Quarterly, 3rd series 35 (Jan. 1978), pp. 3-32.

Higgs, Robert, Competition and Coercion: Blacks in the American Economy, 1865-1914

(Chicago, 1977).

Jones, Alice Hanson, Wealth of a Nation to Be: The American Colonies on the Eve of

the Revolution (New York, 1980).

Margo, Robert, "Accumulation of Property by Southern Blacks: Comment and Further

Evidence," American Economic Review, 74 (Sept. 1984), pp. 768-76.

Mayhew, Anne, "A Reappraisal of the Causes of Farm Protest in the United States,

1870-1900," this JOURNAL, 32 (June 1972), pp. 464-75.

McCusker, John, and Russell Menard, The Economy of British America, 1607-1789

(Chapel Hill, 1985).

McGuire, Robert, "Economic Causes of Late Nineteenth Century Agrarian Unrest:

New Evidence," this JOURNAL, 41 (Dec. 1981), pp. 835-52.

McGuire, Robert, and Robert Ohsfeldt, "An Economic Model of Voting Behavior over

Specific Issues at the Constitutional Convention of 1787," this JOURNAL, 46 (Mar.

1986), pp. 79-111.

North, Douglass, The Economic Growth of the United States, 1790-1860 (New York,

1961).

154

Whaples

North, Douglass, Growth and Welfare in the American Past (New York, 1966).

Ransom, Roger, and Richard Sutch, One Kind of Freedom: The Economic Consequences of Emancipation (New York, 1977).

Reid, Joseph D., Jr., "Economic Burden: Spark to the American Revolution?" this

JOURNAL, 38 (Mar. 1978), pp. 81-100.

Rockoff, Hugh, "The Free Banking Era: A Reexamination," Journal of Money, Credit

and Banking, 6 (May 1974), pp. 141-67.

Romer, Christina, "New Estimates of Prewar Gross National Product and Unemployment," this JOURNAL, 46 (June 1986), pp. 341-52.

Romer, Christina, "The Nation in Depression," Journal of Economic Perspectives, 7

(Spring 1993), pp. 19-39.

Rothenberg, Winifred B., "The Market and the Massachusetts Farmer, 1750-1855,"

this JOURNAL, 41 (June 1981), pp. 283-314.

Temin, Peter, The Jacksonian Economy (New York, 1969).

Temin, Peter, Did Monetary Forces Cause the Great Depression? (New York, 1976).

Weir, David, "The Reliability of Historical Macroeconomic Data for Comparing

Cyclical Stability," this JOURNAL, 46 (June 1986), pp. 353-66.

Whaples, Robert, "Winning the Eight Hour Day," this JOURNAL, 50 (June 1990), pp.

393-406.

Whaples, Robert, and Dianne C. Betts, Historical Perspectives on the American

Economy: Readings in American Economic History (New York, 1994).

Whitten, David 0., "The Depression of 1837: Incorporating New Ideas into Economic

History Instruction-A Survey," Paper presented at the Social Science History

Association meetings, Atlanta, 1994.

Wright, Gavin, "The Economic Revolution in the American South," Journal of

Economic Perspectives, 1 (Summer 1987), pp. 161-78.

You might also like

- Scrap Bill 1 DT 10-09-22Document2 pagesScrap Bill 1 DT 10-09-22Santu ChakrabortyNo ratings yet

- Kenneth Galbraith - Economics and The Public PurposeDocument332 pagesKenneth Galbraith - Economics and The Public PurposeKnowledgeTainment100% (3)

- Apple Inc Case Study MGTDocument58 pagesApple Inc Case Study MGTshahid_mk10100% (3)

- RSM100 Textbook NotesDocument44 pagesRSM100 Textbook NotesSalman SahirNo ratings yet

- Cultures Et Civilisations de La Langue 4 Sequence 1Document3 pagesCultures Et Civilisations de La Langue 4 Sequence 1rosaNo ratings yet

- International Political Economy Beyond Hegemonic StabilityDocument10 pagesInternational Political Economy Beyond Hegemonic StabilityRaikaTakeuchiNo ratings yet

- Corporate FinanceDocument28 pagesCorporate FinanceFelipe ProençaNo ratings yet

- Williamson - 1998 - Globalization, Labor Markets and Policy Backlash in The PastDocument23 pagesWilliamson - 1998 - Globalization, Labor Markets and Policy Backlash in The Paste691295991No ratings yet

- Stages of GrowthDocument25 pagesStages of Growthandrewkyler92No ratings yet

- "Economic Burden: Spark To The American Revolution?" by Joseph D. Reid, Jr.Document21 pages"Economic Burden: Spark To The American Revolution?" by Joseph D. Reid, Jr.pxddqyppxvNo ratings yet

- Wallerstein Changing Geopolitics of The World System C 1945 To 2025Document20 pagesWallerstein Changing Geopolitics of The World System C 1945 To 2025Walter A GuerreroNo ratings yet

- Planting the Seeds of Research: How Americas Ultimate Investment Transformed AgricultureFrom EverandPlanting the Seeds of Research: How Americas Ultimate Investment Transformed AgricultureNo ratings yet

- E J HobsbawmDocument17 pagesE J HobsbawmMandeep Kaur PuriNo ratings yet

- U.S. Slavery and Economic Thought - EconlibDocument11 pagesU.S. Slavery and Economic Thought - EconlibAndres Felipe Ortiz SuspesNo ratings yet

- Global Economic History SurveyDocument43 pagesGlobal Economic History SurveyMark Tolentino GomezNo ratings yet

- Assessing The Obstacles To Industrialisation: The Mexican Economy, 1830-1940Document33 pagesAssessing The Obstacles To Industrialisation: The Mexican Economy, 1830-1940api-26199628No ratings yet

- An Economic Interpretation of The American RevolutionDocument31 pagesAn Economic Interpretation of The American RevolutionShiva GuptaNo ratings yet

- Moses Abramovitz-Thinking About Growth - and Other Essays On Economic Growth and Welfare (Studies in Economic History and Policy - USA in The Twentieth Century) (1989) PDFDocument395 pagesMoses Abramovitz-Thinking About Growth - and Other Essays On Economic Growth and Welfare (Studies in Economic History and Policy - USA in The Twentieth Century) (1989) PDFCarine Vieira100% (1)

- Political Economy Annotated BibliographyDocument3 pagesPolitical Economy Annotated BibliographyAndrew S. Terrell100% (1)

- James Huston - The Early American RepublicDocument14 pagesJames Huston - The Early American RepublicBlackstone71No ratings yet

- Coatsworth Leer TodoDocument26 pagesCoatsworth Leer TodoJohan xNo ratings yet

- Investing in People: The Economics of Population QualityFrom EverandInvesting in People: The Economics of Population QualityNo ratings yet

- In Restraint of Trade - The Business Campaign Against Competition, 1918-1938Document286 pagesIn Restraint of Trade - The Business Campaign Against Competition, 1918-1938FreeWillNo ratings yet

- E1-35-02Document8 pagesE1-35-02yafework400No ratings yet

- Strange CareerDocument22 pagesStrange Careervivek.vasanNo ratings yet

- Commerce and Coalitions: How Trade Affects Domestic Political AlignmentsFrom EverandCommerce and Coalitions: How Trade Affects Domestic Political AlignmentsRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (3)

- Cambridge University Press, Economic History Association The Journal of Economic HistoryDocument20 pagesCambridge University Press, Economic History Association The Journal of Economic HistorybryanNo ratings yet

- The Rise and Fall of Britain's North American Empire: The Political Economy of Colonial America Gerald Pollio 2024 Scribd DownloadDocument57 pagesThe Rise and Fall of Britain's North American Empire: The Political Economy of Colonial America Gerald Pollio 2024 Scribd Downloaddexxmateba47100% (1)

- Johnson Keynesian Revolution Monetarist Counter Rev1816968 PDFDocument15 pagesJohnson Keynesian Revolution Monetarist Counter Rev1816968 PDFLuis Felipe SoteloNo ratings yet

- PDF The Rise and Fall of Britain’s North American Empire: The Political Economy of Colonial America Gerald Pollio downloadDocument34 pagesPDF The Rise and Fall of Britain’s North American Empire: The Political Economy of Colonial America Gerald Pollio downloadeybergietzNo ratings yet

- wood---who-governs.-legislature-2C-bureaucracies-2C-or-markets--282020-29Document277 pageswood---who-governs.-legislature-2C-bureaucracies-2C-or-markets--282020-29huzair8383No ratings yet

- Instant Download Crisis and Sustainability: The Delusion of Free Markets 1st Edition Alessandro Vercelli (Auth.) PDF All ChaptersDocument62 pagesInstant Download Crisis and Sustainability: The Delusion of Free Markets 1st Edition Alessandro Vercelli (Auth.) PDF All Chapterslefiriffer100% (4)

- Wiley Economic History SocietyDocument28 pagesWiley Economic History Societyxandrinos22No ratings yet

- Taylor - 1998 - On The Costs of Inward-Looking Development. Price Distortions, Growth, and Divergence in Latin AmericaDocument29 pagesTaylor - 1998 - On The Costs of Inward-Looking Development. Price Distortions, Growth, and Divergence in Latin Americae691295991No ratings yet

- Power Concentration in World Politics: William R. ThompsonDocument245 pagesPower Concentration in World Politics: William R. ThompsonaramirezbenitesNo ratings yet

- Oil, Illiberalism, and War: An Analysis of Energy and US Foreign PolicyFrom EverandOil, Illiberalism, and War: An Analysis of Energy and US Foreign PolicyNo ratings yet

- Schlefer 2012 Assumptions Economists MakeDocument376 pagesSchlefer 2012 Assumptions Economists Makeclementec100% (1)

- Antonín Basch - The New Economic Warfare-Columbia University Press (2019)Document208 pagesAntonín Basch - The New Economic Warfare-Columbia University Press (2019)nebojsaNo ratings yet

- Art National InterestsDocument5 pagesArt National InterestsDžiksović Ni-DžoNo ratings yet

- A Perilous Progress: Economists and Public Purpose in Twentieth-Century AmericaFrom EverandA Perilous Progress: Economists and Public Purpose in Twentieth-Century AmericaNo ratings yet

- New Comparative Economic HistoryDocument8 pagesNew Comparative Economic HistoryglamisNo ratings yet

- An Economic Interpretation of The American RevolutionDocument31 pagesAn Economic Interpretation of The American RevolutionEdoardo FracanzaniNo ratings yet

- Economic Justice in an Unfair World: Toward a Level Playing FieldFrom EverandEconomic Justice in an Unfair World: Toward a Level Playing FieldRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- The Soulful Science: What Economists Really Do and Why It Matters - Revised EditionFrom EverandThe Soulful Science: What Economists Really Do and Why It Matters - Revised EditionRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Robert L. Schuettinger Eamonn FDocument242 pagesRobert L. Schuettinger Eamonn FW.A.F We Are Friends ExtremeNo ratings yet

- FRIENDS As FOES by Immanuel WallersteinDocument7 pagesFRIENDS As FOES by Immanuel WallersteinEsteban MarinNo ratings yet

- The Mismeasure of Progress: Economic Growth and Its CriticsFrom EverandThe Mismeasure of Progress: Economic Growth and Its CriticsRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (1)

- Causesofthe Industrial RevolutionDocument14 pagesCausesofthe Industrial RevolutionBakhtawar KhanNo ratings yet

- Economic TheoriesDocument4 pagesEconomic TheoriesGlaiza AdelleyNo ratings yet

- Good Thesis For American Revolution EssayDocument6 pagesGood Thesis For American Revolution Essaygjh9pq2a100% (1)

- American Economic AssociationDocument15 pagesAmerican Economic AssociationIpan Parin Sopian HeryanaNo ratings yet

- Goldin 2011 Cliometrics and The NobelDocument20 pagesGoldin 2011 Cliometrics and The NobelAmandine KempkaNo ratings yet

- Alienation and the Soviet Economy: The Collapse of the Socialist EraFrom EverandAlienation and the Soviet Economy: The Collapse of the Socialist EraRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (1)

- Power, Profit and Prestige: A History of American Imperial ExpansionFrom EverandPower, Profit and Prestige: A History of American Imperial ExpansionNo ratings yet

- Inequality As Policy: The United States Since 1979Document10 pagesInequality As Policy: The United States Since 1979Center for Economic and Policy Research100% (1)

- Nolan, Visions of Modernity, Cap.4,6,9 y 10Document48 pagesNolan, Visions of Modernity, Cap.4,6,9 y 10Alejandro BokserNo ratings yet

- Dudley Seers-The Birtth - Life and Death of Development Economics PDFDocument14 pagesDudley Seers-The Birtth - Life and Death of Development Economics PDFCarlos TejadaNo ratings yet

- 46 Clase Magistral Phelps EngDocument10 pages46 Clase Magistral Phelps EngSophie- ChanNo ratings yet

- After the Fall: The Inexcusable Failure of American Finance: An Update to Bad Money (A Penguin Group eSpecial from Penguin Books)From EverandAfter the Fall: The Inexcusable Failure of American Finance: An Update to Bad Money (A Penguin Group eSpecial from Penguin Books)Rating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (61)

- Digital History Meets MicrobloggingDocument10 pagesDigital History Meets MicrobloggingArmando MartinsNo ratings yet

- Pushing BackDocument44 pagesPushing BackArmando MartinsNo ratings yet

- VDEM MethodDocument30 pagesVDEM MethodArmando MartinsNo ratings yet

- Female Labor Force ParticipationDocument15 pagesFemale Labor Force ParticipationArmando MartinsNo ratings yet

- Rapid Appraisal MethodsDocument230 pagesRapid Appraisal MethodsArmando Martins50% (2)

- Guide: Rapid Approaches To Data CollectionDocument22 pagesGuide: Rapid Approaches To Data CollectionArmando MartinsNo ratings yet

- Take The Q TrainDocument46 pagesTake The Q TrainArmando MartinsNo ratings yet

- Taleb TestimonyDocument10 pagesTaleb TestimonyArmando MartinsNo ratings yet

- The Institutional Foundations of Public Policy A Transactions Approach With Application To ArgentinaDocument26 pagesThe Institutional Foundations of Public Policy A Transactions Approach With Application To ArgentinaArmando MartinsNo ratings yet

- Healthcare Reform in The Republic of Georgia A Healthcare Reform Roadmap For Post Semashko Countries and Beyond PDFDocument64 pagesHealthcare Reform in The Republic of Georgia A Healthcare Reform Roadmap For Post Semashko Countries and Beyond PDFArmando MartinsNo ratings yet

- David L. Olson, Desheng Wu - Predictive Data Mining Models (2nd Ed.) - Springer (2020)Document127 pagesDavid L. Olson, Desheng Wu - Predictive Data Mining Models (2nd Ed.) - Springer (2020)ruygarcia75No ratings yet

- E-Business Roadmap For SuccessDocument361 pagesE-Business Roadmap For SuccessFeri LeeNo ratings yet

- Amdocs Oss Helps Optimus Deliver Service Excellence Over Next Generation Network and Fiber-To-The-Home InfrastructureDocument6 pagesAmdocs Oss Helps Optimus Deliver Service Excellence Over Next Generation Network and Fiber-To-The-Home InfrastructureMemo VegaNo ratings yet

- Lesson 8 - Functions of Management - Communicating 1Document86 pagesLesson 8 - Functions of Management - Communicating 1Rafael AclanNo ratings yet

- 13th Oct - Quotation - WAFI AGRO COMMODITIES FZ-LLCDocument1 page13th Oct - Quotation - WAFI AGRO COMMODITIES FZ-LLCNgoc AnhNo ratings yet

- TFL Pension Fund - Notice of EGM - March 2014Document2 pagesTFL Pension Fund - Notice of EGM - March 2014RMT London CallingNo ratings yet

- How to Grow Your Small Business EnDocument7 pagesHow to Grow Your Small Business EnBiruktawit DawitNo ratings yet

- Break Down Maintenance S.NO Process Step Description Solution Description Performed BY Transaction Code RemarksDocument3 pagesBreak Down Maintenance S.NO Process Step Description Solution Description Performed BY Transaction Code RemarksRAMAKRISHNA.GNo ratings yet

- Godrej Prana Price SheetDocument10 pagesGodrej Prana Price Sheetbigdealsin14No ratings yet

- Bmath ExamDocument9 pagesBmath ExamMarie Joy Pelaez75% (4)

- Sports Sponsorship in AthleteDocument7 pagesSports Sponsorship in AthleteZulfadhli AtemanNo ratings yet

- Birth of WestsideDocument13 pagesBirth of WestsideKomal MedhaNo ratings yet

- Guide Mqa 005 - VMPDocument7 pagesGuide Mqa 005 - VMPAnil SaxenaNo ratings yet

- A Presentation On Analysis of Working Capital Management & Ratio Analysis For Kaira District Cooperative Milk Producers Union Ltd. (AMUL)Document18 pagesA Presentation On Analysis of Working Capital Management & Ratio Analysis For Kaira District Cooperative Milk Producers Union Ltd. (AMUL)dairymilk2010No ratings yet

- Marginal Costing: Shikha SharmaDocument13 pagesMarginal Costing: Shikha Sharmadeepakarora201188No ratings yet

- Mod (MCQ)Document32 pagesMod (MCQ)bijay100% (1)

- Final Travel Reimbursement Form - FinalDocument1 pageFinal Travel Reimbursement Form - FinalYogesh RathiNo ratings yet

- Strategic Manage Men 1Document46 pagesStrategic Manage Men 1Ahtesham AnsariNo ratings yet

- Creating Your Unique Trading PlanDocument7 pagesCreating Your Unique Trading PlanSham GareNo ratings yet

- HDFC and Icici Bank Final ReportDocument19 pagesHDFC and Icici Bank Final ReportSahib SinghNo ratings yet

- 2007 Revised Rules in The Availment of Income Tax HolidayDocument23 pages2007 Revised Rules in The Availment of Income Tax HolidayArchie Guevarra100% (1)

- Uxpin The Elements of Successful Ux Design PDFDocument108 pagesUxpin The Elements of Successful Ux Design PDFFarley Knight100% (1)

- Social Marketing Concepts and PrinciplesDocument4 pagesSocial Marketing Concepts and PrinciplesProfessor Jeff FrenchNo ratings yet

- Submitted by - Faculty of Management ST - Jhon'S College, Agra Mail IdDocument26 pagesSubmitted by - Faculty of Management ST - Jhon'S College, Agra Mail IdNarendra RawatNo ratings yet

- Ak 1991884221-1560333289 PDFDocument1 pageAk 1991884221-1560333289 PDFKuchibhotla Madhava SastryNo ratings yet

- Lease Modules ContinuedDocument8 pagesLease Modules ContinuedMariz RapadaNo ratings yet

- Baby Business Plan FormatDocument8 pagesBaby Business Plan FormatyvetteNo ratings yet