Castanet - Gerard Grisey and The Foliation of Time

Castanet - Gerard Grisey and The Foliation of Time

Uploaded by

clementecollingCopyright:

Available Formats

Castanet - Gerard Grisey and The Foliation of Time

Castanet - Gerard Grisey and The Foliation of Time

Uploaded by

clementecollingOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Castanet - Gerard Grisey and The Foliation of Time

Castanet - Gerard Grisey and The Foliation of Time

Uploaded by

clementecollingCopyright:

Available Formats

This article was downloaded by: [Hebrew University]

On: 20 February 2012, At: 00:45

Publisher: Routledge

Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House,

37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK

Contemporary Music Review

Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information:

http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/gcmr20

Grard Grisey and the foliation of time

P.A. Castanet & Joshua Fineberg

Available online: 20 Aug 2009

To cite this article: P.A. Castanet & Joshua Fineberg (2000): Grard Grisey and the foliation of time, Contemporary Music

Review, 19:3, 29-40

To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/07494460000640351

PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE

Full terms and conditions of use: http://www.tandfonline.com/page/terms-and-conditions

This article may be used for research, teaching, and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic

reproduction, redistribution, reselling, loan, sub-licensing, systematic supply, or distribution in any form to

anyone is expressly forbidden.

The publisher does not give any warranty express or implied or make any representation that the contents

will be complete or accurate or up to date. The accuracy of any instructions, formulae, and drug doses should

be independently verified with primary sources. The publisher shall not be liable for any loss, actions, claims,

proceedings, demand, or costs or damages whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in

connection with or arising out of the use of this material.

Contemporary Music Review

2000, Vol. 19, Part 3, p. 29-40

Photocopying permitted by license only

9 2000 OPA (Overseas Publishers Association) N.V.

Published by license under

the Harwood Academic Publishers imprint,

part of Gordon and Breach Publishing,

a member of the Taylor & Francis Group.

Downloaded by [Hebrew University] at 00:45 20 February 2012

G4rard Grisey and the Foliation of

Time

P. A. Castanet

Translated by Joshua Fineberg

KEY WORDS:

G6rard Grisey; Itin6raire; spectral music; musical time; process.

In the midst of the grayish panorama of contemporary music, among the

creators of the post-war generation, G6rard Grisey (born in 1946) has

been composing in solitude for more than twenty-five years. Thus, at the

center of the laboratory of European musical science, a universe which

steadfastly prefers sterility and acceptance to the smoldering isolation of

a more personal route, G6rard Grisey has remained a true composer,

determined and unique, possessing a vast amount of technique and

profound instinct for realizing musical works.

A shared sensibility

In the 20th century numerous composers have made use of nature in its

raw form, as musical material. Water, wind, fire, along with various other

naturally produced phenomena have been recorded or created in concert,

offering composers (such as Mache, Messiaen, Xenakis, Kagel ...) a

collection of instruments rich in parametric possibilities. However, in the

early seventies a different aspect of nature - - the organic, living, acoustic

nature of sound - - strongly influenced a few research-minded musicians.

Immersed in science and philosophy, with a hunger for technological

progress and with consideration for the cultural as well as physical

aspects of sound, Tessier, Murail, Grisey, Levinas, Dufourt, who would

29

30 P.A. Castanet

Downloaded by [Hebrew University] at 00:45 20 February 2012

guide the development of the ensemble l'Itin6raire in Paris, began, each

in their own way, the route towards, what Hugues Dufourt called in his

now historical article, "Spectral Music". Following a long line of eminent

scientists, going from Galileo or Descartes to Newton or Saveur and

touching upon the 'concomitant sounds' of Father Marin Mersenne, the

'spectral' composers began hawking a n e w idea and formed a new

'school.' In the middle of this group of experimenters, extolling the

virtues of the 'ecology' of musical source material, Grisey would work

diligently on the 'evolution of sound 1' focusing aesthetically on both

musical and temporal issues.

Sonic archeology, musical

mythology

Without going back to mythological references such as the Gandharva, the

stories and legends of China, the diphonic vocal techniques of

Mongolian H66mi singers or the techniques of the peasants of Touva,

consideration of natural acoustic phenomena highlighting a fundamental

note and its colored train of upper partials has effected m a n y postromantic musicians (from Debussy, Hindemith, Scriabin, Var6se, Jolivet,

Scelsi and Messiaen to Radulescu, Vivier, Per Norgaard ... ). In the wake

of this cosmopolitan movement, confronted with the hippie-like happenings that grew out of the culture inspired by the student uprisings in

Paris in May 1968, and in opposition to Pierre Boulez's Domaine Musical

and its image of compositional technique within a vacuum, a group of

Parisian composers and instrumentalists founded the ensemble

l'Itin6raire in 1973.

With the approval of Olivier Messiaen, this group's first efforts cried

out for listening to the sounds themselves, for a musical 'language' and

'syntagm' based on a profound use of sonic phenomena in all their complexity, both harmonic and (youth and creative greed oblige) inharmonic.

Those most concerned with the overall relationships of phenomenological sonic material (of this group of composers, only Dufourt was not

Messiaen's student) are clearly G6rard Grisey and Tristan Murail along

with Michael Levinas, to a lesser degree. Although a bit late, a spirit of

modified micro-spectrality is felt in certain recent works of Levinas: for

example, Rebonds (1993), Diaclase (1993), Par-Del~ (1994) and the work

1. translator's note: the expressionused in French is 'devenir du sonore,"this implies the

sonic evolution as projectedinto the work's future: the sound's becomingwhat it will

become.

Girard Grisey and the Foliation of Time 31

Downloaded by [Hebrew University] at 00:45 20 February 2012

which synthesizes much of the research in the other pieces, the opera

GO-gol (1994). In as much as his music makes no use of micro-intervals

and in opposition to the generally held view, Hugues Dufourt must be

considered a sort of 'faux-spectral' composer. As for Roger Tessier, he

only dealt obliquely with the techniques offered by spectral music, only

occasionally using the solipsistic concept of a single sound as the basis

for a piece (Clair-Obscur for soprano, instrumental trio and electroacoustic treatments - - 1977, Coalescence for clarinet and two orchestras

- - 1987).

The artifice of nature

The works of Grisey from 1970-1980 contain at once self-generative phenomena and self-destructive ingredients. Extracted from the mega-cycle

Les Espaces Acoustiques (1975-1985), Modulations (1976-1977), for

example, shows acoustic zones in perpetual motion around a fundamental E (41.2 Hertz). In this piece, where at each instant the material seems

to be hoarding to itself the fragile allegory of self-genesis, the form itself

recounts 'the history of the sounds of which it is made.' Moreover, in the

same instrumental cycle, the composers attempts - - with Partiels (1975)

- - to synthesize more richly the spectrum of a single note played on the

trombone using sixteen instruments for the task. An analytical use of

sonograms of brass instruments along with spectrograms of the transformations caused by adding various mutes, allow the synthetic reconstruction of the globality of the timbre or, on the contrary, facilitate its

controlled distortion. The general concepts of perturbation and erosion,

read entropy, are the purview not only of Partiels but also of Chants de

l'Amour (1981-1984), for mixed voices and computer synthesized voice.

Using the program Chant, created at IRCAM (Paris) by Xavier Rodet

and Yves Potard, Grisey was able to realize a continuous voice and two

streams of extraordinary respiratory pulsations. However, while the

success of this piece owes much to cutting edge technology, it also owes

a debt to the rigorous structures used by the polyphonic music of the

fifteenth century (mainly Guillaume Dufay - - 1400-1474 - - and

Johannes Ockeghem - - 1410-1497) and to the games of Pygmies from

the Lituri region. Additionally, the synthetic voice functions as a referential model for the live singers, performing a similar role to the Tampura

of Indian music. The machine voice can assume the roles of both Beauty

and the Beast. "In turn divine, monstrous, threatening, seductive, both a

mirror and a projection of all the fantasies of the h u m a n voice," this

instrumental source "copies and multiplies itself into a crowd" explains

Downloaded by [Hebrew University] at 00:45 20 February 2012

32

P. A. Castanet

N,

o

~

o=

~o

,.o

Downloaded by [Hebrew University] at 00:45 20 February 2012

G~rard Grisey and the Foliation of Time 33

the composer (listen to the duo titled 'I love you' which unleashes a sonic

vision worthy of Dante's hell: a crowd of lovers is depicted b y thousand

of voices which call out to each other, swirling around then collapsing).

Freely personified, the breath - - dare we call it the anima? - - learns to

live, to breathe, to sing, to move, to stammer, then finally to speak

twenty-two different languages. Staged in the theater of life, the spatiosonic relations of the man-chorist with the machine-singer is made up of

both fusion and interaction, of conflict and phagocytosis b u t also the

false autonomy of many types of dialogue (of belligerents, of friends, of

tender confidence).

Two more examples: first, look at the middle section in which a system

of alternating echoes between the human and robot voices is established

(see Figure 1), then consider the touching scene where the chorus sings a

last lullaby then drifts off into sleep, dreaming in the snore of the electronic monster. "Supreme seduction," Grisey told us, "that voice risks

being more human then a natural voice, both more pure and more

painful." As can be seen, the true division between natural and unnatural has clearly, and happily, become very artistically vague.

In fact G6rard Grisey, a curious and intelligent aesthete, likes the truth

of nature. He uses, to this end, fine distortions and precise blurs. Charles

Ives said of nature that "she likes analogies but she hates repetition." If

Dufourt strangles the beautiful nature of the encyclopedists (and the pastoral flute - - think of A n t i p h y s i s - - 1978) and if Murail plays at warping

mechanical systems (reread the pretext for the ground rules of Mdvnoire

l~rosion - - 1976), Grisey has subtly harmonized the laws of a curiosity

inspired craftsmanship. Going from a system of timbro-temporal deformation to a controlled spatio-harmonic dilation, Grisey's imprint never

breaks the thread of his continuous preoccupation with temporal metamorphoses. Furthermore, the archetypal times of nature move freely

between the movements of V o r t e x T e m p o r u m (1994-1995) "in constant

times as different as those of humans (the time of language and the time

of respiration), that of whales (the spectral time of sleep rhythms) and

that of birds or insects (extremely contracted time where the borders

become blurred)," explains the composer.

Delicate violence and real~false nature

In the same w a y that the scenes of slight 'catastrophes' suspended by the

mathematician Ren6 Thorn or in the same tendency manifested in the

pictures showing the imprecise crossing of the border from indigo to

violet in the experiments of N e w t o n on the dispersion of light, some

Downloaded by [Hebrew University] at 00:45 20 February 2012

34

P. A. Castanet

pages from Grisey's work discreetly reveal the indescribable paradox or

the impossible dialectic. Jour, Contre-jour (1978-1979) is an exact image of

a quasi-virtual passage of the progression 'from daily time to musical

time.' As in Partiels, the imagination perceives the timbral lighting, in

extremely special halftone colors, as sweeping movements from shadow

to clarity, exposing impressions of a jumble, now nocturnal, now diurnal.

Le Noir de I ~.toile (1989-1990), written for six percussionists placed

around the audience, integrates into the sonic discourse a music created

by the speed of rotation of two pulsars (the residue of a Super Nova):

one called V61a (in French) was prerecorded and the other is captured

'live" by radio telescope. The troubling effect of the re-transmitted periodico-astronomic sounds of this neutron star comes in part from the fact

that the sounds are the result of the audible transcoding of the electromagnetic waves that make up a portion of the star's 'light" and also

because the sounds that have finally become audible have taken at least

fifteen thousand years to reach us.

For those wanting to study more closely Grisey's continuous transitions, his parametric dovetailing or his aesthetic mediations, an in

depth study of Partiels or Talea might prove useful. Concerning Partiels,

and outside of the analysis of the classic parameters, an informed

listener could concentrate on the following dichotomies (see the table

below):

dynamic p o l e

durations

phasing

time

ppp

FFF

strict notation

repetition ad-lib,

periodic

aperiodic

striated

non-pulsated

kinetic, spatio-temporal activity

rhythm

agogic

passive (fermata) sometimes free

active

sometimes free

poly-tempi

release

tension

sonic genesis

aesthetic

biomorph (natural model)

technomorph (electronic model)

organic nature

artificial noise

Downloaded by [Hebrew University] at 00:45 20 February 2012

GErard Grisey and the Foliation of Time 35

pitch

sound

timbre

relation

material

spectral

cluster

sinusoidal

noisy

pure

dirty

consonant

dissonant

homogeneous

heterogeneous

character

luminosity

density

smooth material

clear

grainy material

dark

single sound/two part spectral

band ( 2 ft.)

tutti - - each instrument deploying

its own network of harmonics

dramaturgy

process

dynamic and timbric

visual and scenic

purification

contamination by parasite

More recently, Le Temps et l'~cume (1988-1989) for four percussionists, two synthesizers and chamber orchestra contains pairs of instruments rigorously written in 'false-unisons' or 'false-octaves.' Similarly,

Vortex Temporum II (1994-1995) for sextet, leaves the pianist with the

feeling of being free, but under surveillance as regards the means of

circumscribing the metronomic stability: "to give the impression of hesitation to the tempo (accelerando or rallantando)" ... "to create a blurred

periodicity using slight fluctuations around a constant," writes Grisey

on the conductor's score, along with the dedication to Salvatore

Sciarrino.

Mnemosyne exposed

G6rard Grisey looks for inspiration in the richness of extra-European art

and philosophy: in this regard, the poly-metric ritual of Tempus ex

machina (1979) for six percussionists must be considered as well as the

spatial disposition and accumulating stratification of temporalities of

L'Ic6ne Paradoxale (homage to Piero della Francesca - - 1993-1994 for two

w o m e n ' s voices and large orchestra divided into two groups). The

Egyptian symbolic codification inspired b y The Book of the Dead was

used in Anubis-Nout (1983-1988) and a desire to bring out the 'myth of

Downloaded by [Hebrew University] at 00:45 20 February 2012

36

P. A. Castanet

duration' is present in Vortex Temporum III and in St~le (1995). All of these

examples serve as so m a n y cultural clues to a need which is musical,

above all else. St~le - - duo for percussion dedicated to Dominique

Troncin - - bears a heading with the following symptomatic phrases:

"How can a cellular organization be made to emerge from a flow which

obeys other laws? How can you sketch with precision and at the edge of

silence, a rhythmic inscription, first indiscernible then finally in an

archaic hammering? While composing, an image came to me: that of

archeologists discovering a stele and cleaning its surface until its funeral

inscription becomes visible."

See, in Figure 2, the bi-tempic use of the contrabass tom and very low

bass d r u m extracted from St~le. The motion of the represented space is

built upon two simultaneous processes. The first rule governs the superposition of the different tempi (quarter note = 40 for the tom, quarter

note = 45 or slower for the bass drum); the second controls the evolution

towards disappearance of the rhythmic cells that nourish it (longer and

longer rhythmic values for the tom, a cellular game of variable durations

with stopping points for the bass drum).

Grisey is no stranger to the secular archetypes of occidental music,

either. To illustrate this, take Modulations (1976-1977), for example. A

canon of neumes crystallizes in a polyphony of blocks; in which can be

observed the independence of structural models. Additionally, the application 'in situ' of the medieval idea of the talea influencing the disassociation of rhythms and pitches, the color, is manifested in Talea (1986).

Remember that Michael Levinas wrote something along the same order

with Arsis and Thdsis in 1971. We should also try to understand the

Griseyist idea of (re)considering the aura of sympathetic resonance that

is wrapped around the ancient notion of m o n o d y in Prologue (1976), the

first piece of the Espaces Acoustiques. Looking through this prism, with

its almost didactic connotations, the presence of zones of coherence can

be seen - - close in some ways to the ancestral apparatus of occidental

tonality - - within the complex stratagraphy that sculpts the interior of

Vortex Temporum (1994-1995). We can finally judge the lyrical interplay

of duplication, spectral ambiguity, ambivalence and consonance in

L'Ic6ne Paradoxale (1993-1994). In that recent work, the orchestra is spatialized as two times two ensembles: the large orchestra is divided into

low instruments and high ones and a small phalanx is split into two

symmetrical groups which envelope the two female voices. A close relation is created to the visual logic of Piero della Francesca's famous painting, La Madonna del Parto. Explicit references are given by Grisey in the

title, through the distribution of the orchestral ensembles and also

through the structure of the piece. While the form of the work 'traces two

contrary evolutions, analogous to two diagonals whose intersection

Downloaded by [Hebrew University] at 00:45 20 February 2012

G~rard Grisey and the Foliation of Time 37

i

,.0

.,.4

8

O

m

e~

87

Illl ~

i

E

I,

LD

ml

Downloaded by [Hebrew University] at 00:45 20 February 2012

38

P. A. Castanet

makes up the middle section,' the temporal material - - foliated into different levels as in Vortex Temporum - - uses here 'the proportions which

underlie the composition of the fresco: 3-5-8-12.'

The composer explains that in this way the Time I is 'extremely compressed.' High pitched instruments of the large orchestra play a compressed version of the entire piece in 16 seconds, "like the view of a

painting from very far away, where only a vague distribution of colors

and forms can be distinguished." This reduction in format is perceived

through fragmentary progressions and repetitions.

Time II tries to be 'linguistic.' With the accompaniment of the small

orchestra, the soprano and mezzo-soprano perform a slow evolution,

starting from vowels and moving toward consonants, from color to

attain noise-like sounds, sustained notes standing against the rhythms.

In opposition to the timbral principals of Time I, Time III is somewhat

related to the linguistic content of Time 1I, but dilated. Here, it is the low

instruments of the large instrumental group that "articulates in slowmotion the 'noise' of consonants contained in the different signatures of

Piero della Francesca (in Latin and Italian)."

Diametrically opposed to the radicality of Time I, "Time IV is

extremely dilated." The entire large orchestra presents a slow spectral

punctuation which, from the beginning to the end of the piece, as

always in Grisey's music, determines the presence of the different harmonic fields.

G6rard Grisey concludes the prefatory notes to L'Ic3ne Paradoxale in

this way: "When Time II and Tn-ne III cross at the intersection of the diagonals, a continuous and periodic rotation invades the entire available

sonic space." The score ends with a three part temporal foliation (an accumulation of times I, II and IV) followed by a short coda recapitulating all

the spectral material.

The measured passage of the century and history

The recent pieces of Tristan Murail avoid a priori processes that are too

clearly predictable from the outside. If musical content seems to have

calmed a bit, while still continuing its evolution within the directional

time of spectral music, form seems to have become truly more complex.

Analyze, for example, the use of the principal of fractals in Serendib for

22 instruments (1991-1992) the creation of a paradoxical flow (impact of

the micro-logic and a sudden bifurcation of the macro-formal structure)

in La Dynamique des Fluides for orchestra (1992), the cleavage of the

structural layout for La Barque Mystique for quintet (1993) or the rhythmic

Downloaded by [Hebrew University] at 00:45 20 February 2012

G~rard Grisey and the Foliation of Time 39

vortexes (organized by the idea of a spiral centered on multiple ostinati)

in La Mandragore for piano (1993).

Hugues Dufourt works with a new typology of duration, transgressing

the strictures of traditionally assignable forms. In the same way as for a

pagan ritual, he tries to suppress all external references and all articulations which are too connotated. Look at the extreme auto development in

the progression of the Philosophe selon Rembrandt for orchestra

(1987-1992), or the intelligent manipulations of parametric perspective

in The Watery Star for octet (1993) erasing at once harmony, timbre and

pulse to create the inextricabilis of instrumental fusion. At the recent premiere of L'Espace aux Ombres (1994-1995), the composed evoked the

quarrel which has framed the last ten years, modernism vs. post-modernism. According to Dufourt, this conflict can doubtlessly find a "constructive solution," leading to a "synthesis of styles" and giving birth to

"an original from of art." One of the real problems facing current musical

creation is "that of re-using tradition." "The relation to past attachments

does not, however, cry out for vain repetition. On the contrary, it has

become essential to re-evaluate the craft of musical composition, to pick

back up the thread of history, with neither eclecticism nor technical

obsession." Infine, the basic question presented by the author of L'Heure

des Traces was phrased in the following way: "How can we renew our

relationship with tradition without giving these renovations a traditional

form?"

G6rard Grisey solemnly swore to us that, like many people today, he

has stopped believing in an infinitely rosy future and that the notion of

"enlarging the field of consciousness in concentric circles" seems to have

become preferable, today, to that of progress. Following Dufourt's

example, Levinas seems to have kept some distance from the ardent

flames of technology to embrace the acoustic body in its brute form, free

from the artifice of Magical Electricity. Moreover, while Dufourt thinks

that 'the orchestra is still the best synthesizer we have,' Grisey is moving

slowly away from the sphere of art-science in which he had total

confidence in earlier decades (1970s-1980s). Today, Grisey tends to

denounce the plethora of orgiastic sounds and the almost unlimited

breadth of scale systems which, according to him, will not necessarily

produce viable long-term solutions.

Thus history has never stopped following its long, chaotic but uninterrupted, rocket ride of referential or even irreverent events. If serious listening to Le Temps et l'~cume by Grisey evokes a certain heritage from

Debussy, scrutinizing certain pages of Jour, Contre-jour, inevitably calls

to mind a certain kinship to Ligeti. In this way, leaving the circular

matrix that encloses the ideas of Messiaen and Stockhausen, camped at

the end of a boundary line linking the three 'ees' (Debussy, Scelsi and

Downloaded by [Hebrew University] at 00:45 20 February 2012

40

P. A. Castanet

Ligeti), Grisey searches, listens, evolves, lives and opens. "You have to

open up in order to live better within the enclosed garden of sonic

images. Listen then meditate, then listen again," advises the composer of

Chants de l'Amour in an article printed in the Cahiers du Renard.

In this way, other unexpected influences have marked the pieces with

a more recent spectral essence: from the rhythmic sedimentation, that

comes from extra-European musical practices, to the original concept of

vertiginous repetition, dear to Morton Feldman, passing through the

incisive rapidity of short objects in the manner of Janacek, or the swirling

treatment of distinctive material in the manner of a Ravel quotation for

Vortex Temporum L K III '... to be continued.' Raymond Queneau wrote,

during World War II, that the truly great history was the history of inventions. "It is they which provoke history, based on statistical, biological

and geographic data" ... At the d a w n of the XXIst century and in

our specialty, might we not add to this perspective credo the adjective

'musicological'?

You might also like

- Inception - Time (Hans Zimmer) Fingerstyle TabDocument1 pageInception - Time (Hans Zimmer) Fingerstyle TabSidney SidNo ratings yet

- György Kurtág Officium Breve in Memoriam Andreae Szervánszky B. FrandzelDocument15 pagesGyörgy Kurtág Officium Breve in Memoriam Andreae Szervánszky B. Frandzelclementecolling100% (1)

- DAMSCHRODER David 2008 Thinking About Harmony Historical Perspectives On AnalysisDocument343 pagesDAMSCHRODER David 2008 Thinking About Harmony Historical Perspectives On Analysisclementecolling100% (6)

- Bridgewater HallDocument4 pagesBridgewater HallHuzaifa J AhmedabadwalaNo ratings yet

- Resounding the Sublime: Music in English and German Literature and Aesthetic Theory, 1670-1850From EverandResounding the Sublime: Music in English and German Literature and Aesthetic Theory, 1670-1850No ratings yet

- David Bundler - Grisey InterviewDocument5 pagesDavid Bundler - Grisey Interviewmarko100% (1)

- Mahler and New Music - G. NebelDocument4 pagesMahler and New Music - G. NebelbraisgonzalezNo ratings yet

- Jonathan Bernard VareseDocument26 pagesJonathan Bernard Vareseclementecolling100% (1)

- TELLUR Tristan MurailDocument9 pagesTELLUR Tristan MurailclementecollingNo ratings yet

- Decentering Musical Modernity: Perspectives on East Asian and European Music HistoryFrom EverandDecentering Musical Modernity: Perspectives on East Asian and European Music HistoryTobias JanzNo ratings yet

- Musically Sublime: Indeterminacy, Infinity, IrresolvabilityFrom EverandMusically Sublime: Indeterminacy, Infinity, IrresolvabilityNo ratings yet

- Festa BRAVODocument59 pagesFesta BRAVOJuan Domingo Cordoba Agudelo100% (1)

- Birtwistle Games - Philarmonia OrchestraDocument30 pagesBirtwistle Games - Philarmonia OrchestraMarco Lombardi100% (1)

- "I HEREBY RESIGN FROM NEW MUSIC" by Michael RebhahnDocument5 pages"I HEREBY RESIGN FROM NEW MUSIC" by Michael RebhahnRemy Siu100% (1)

- Stockhausen On OperaDocument17 pagesStockhausen On OperaMikhaelDejanNo ratings yet

- The New Music From NothingDocument28 pagesThe New Music From NothingPhasma3027No ratings yet

- Thomas Adès Mahler: Alan Gilbert and The New York PhilharmonicDocument11 pagesThomas Adès Mahler: Alan Gilbert and The New York PhilharmonickmahonchakNo ratings yet

- A Study in Semiological AnalysisDocument99 pagesA Study in Semiological AnalysisOlga SofiaNo ratings yet

- The Road To Plunderphonia - Chris Cutler PDFDocument11 pagesThe Road To Plunderphonia - Chris Cutler PDFLeonardo Luigi PerottoNo ratings yet

- THORESEN Spec-Morph Analysis Acc SchaefferDocument13 pagesTHORESEN Spec-Morph Analysis Acc SchaefferAna Letícia Zomer100% (1)

- 2014-Milwaukee Stuff About Temporal CanonsDocument303 pages2014-Milwaukee Stuff About Temporal CanonsMichael NorrisNo ratings yet

- Gregory G. Butler-Fugue and RhetoricDocument62 pagesGregory G. Butler-Fugue and Rhetoricsopranopatricia100% (2)

- Reish ScelsiDocument43 pagesReish ScelsiAgustín Fernández BurzacoNo ratings yet

- The Style Incantatoire in André Jolivet's Solo Flute WorksDocument9 pagesThe Style Incantatoire in André Jolivet's Solo Flute WorksMaria Elonen100% (1)

- L'objet SonoreDocument10 pagesL'objet SonoreipiresNo ratings yet

- Lerdahl Jack End Off Generative Theory Tonal MusicDocument11 pagesLerdahl Jack End Off Generative Theory Tonal MusicOscar MiaauNo ratings yet

- Composer Interview Helmut-1999Document6 pagesComposer Interview Helmut-1999Cristobal Israel MendezNo ratings yet

- Boulez, Pierre (With) - The Man Who Would Be King - An Interview With Boulez (1993 Carvin)Document8 pagesBoulez, Pierre (With) - The Man Who Would Be King - An Interview With Boulez (1993 Carvin)Adriana MartelliNo ratings yet

- Practicalities of A Socio-Musical UtopiaDocument13 pagesPracticalities of A Socio-Musical UtopiaJoshua CurtisNo ratings yet

- Harley Konrad 201406 PHD Thesis PDFDocument271 pagesHarley Konrad 201406 PHD Thesis PDFTutu TuNo ratings yet

- Integrating Analytical Elements Through Transpositional Combination in Two ... CrumbDocument93 pagesIntegrating Analytical Elements Through Transpositional Combination in Two ... CrumbJimmy John100% (1)

- Tempus Ex Machina PDFDocument38 pagesTempus Ex Machina PDFFlorencia Rodriguez Giles100% (1)

- 01 Cook N 1803-2 PDFDocument26 pages01 Cook N 1803-2 PDFphonon77100% (1)

- New Music and The Crises of MaterialityDocument49 pagesNew Music and The Crises of MaterialityAlexandros SpyrouNo ratings yet

- Nuclei and Dispersal in Luigi Nono's A Carlo Scarpa Architetto, Ai Suoi Infiniti Possibili' Per Orchestra A MicrointervalliDocument18 pagesNuclei and Dispersal in Luigi Nono's A Carlo Scarpa Architetto, Ai Suoi Infiniti Possibili' Per Orchestra A MicrointervalliFrancesco MelaniNo ratings yet

- Anton Webern On Schoenberg MusicDocument18 pagesAnton Webern On Schoenberg MusicnavedeloslocosNo ratings yet

- Layers of Meaning in Xenakis' PalimpsestDocument8 pagesLayers of Meaning in Xenakis' Palimpsestkarl100% (1)

- Leibowitz and BoulezDocument16 pagesLeibowitz and BoulezScott McGillNo ratings yet

- FERNEYHOUGH, Form-Figure-Style PDFDocument10 pagesFERNEYHOUGH, Form-Figure-Style PDFryampolschi100% (1)

- "The Concept of 'Alea' in Boulez's 'Constellation-Miroir'Document11 pages"The Concept of 'Alea' in Boulez's 'Constellation-Miroir'Blue12528No ratings yet

- Luigi Nono S Late Period States in DecayDocument37 pagesLuigi Nono S Late Period States in DecayAlen IlijicNo ratings yet

- (Article) Momente' - Material For The Listener and Composer - 1 Roger SmalleyDocument7 pages(Article) Momente' - Material For The Listener and Composer - 1 Roger SmalleyJorge L. SantosNo ratings yet

- The Composer As ProcessDocument24 pagesThe Composer As ProcessMariló Soto Martínez100% (1)

- Towards A Grammatical Analysis of Scelsi's Late MusicDocument26 pagesTowards A Grammatical Analysis of Scelsi's Late MusicieysimurraNo ratings yet

- Roig Francoli CH 3 PDFDocument22 pagesRoig Francoli CH 3 PDFLucia Marin100% (1)

- Goal Directed BartokDocument9 pagesGoal Directed BartokEl Roy M.T.No ratings yet

- Redefining Coherence: Interaction and Experience in New Music, 1985-1995Document306 pagesRedefining Coherence: Interaction and Experience in New Music, 1985-1995Mark HutchinsonNo ratings yet

- A Lesson From Lassus (P. Schubert) PDFDocument27 pagesA Lesson From Lassus (P. Schubert) PDFanon_240627526No ratings yet

- Evolution of Tonal Organiztion PDFDocument36 pagesEvolution of Tonal Organiztion PDFmarcela paviaNo ratings yet

- After The Opera (And The End of TheDocument14 pagesAfter The Opera (And The End of TheJuliane AndrezzoNo ratings yet

- Conversations With Igor Stravinsky (1952), Ed. by Robert CraftDocument19 pagesConversations With Igor Stravinsky (1952), Ed. by Robert CraftSunGoddess2010No ratings yet

- The Composition of Elliott Carters Night Fantasies PDFDocument25 pagesThe Composition of Elliott Carters Night Fantasies PDFThayse Mochi100% (2)

- Cornicello, A. Timbre and Structure in Tristan Murail's Désintégrations PDFDocument90 pagesCornicello, A. Timbre and Structure in Tristan Murail's Désintégrations PDFAugusto Lopes100% (1)

- Unnecessary Music Kagel at 50Document3 pagesUnnecessary Music Kagel at 50MikhaelDejanNo ratings yet

- Goldman, Boulez Explosante Fixe PDFDocument37 pagesGoldman, Boulez Explosante Fixe PDFerhan savasNo ratings yet

- Goeyvaerts Paris DarmstadtDocument21 pagesGoeyvaerts Paris DarmstadtDavid Grundy100% (1)

- Xenakis Formalized MusicDocument201 pagesXenakis Formalized Musicgiovanni23No ratings yet

- Music and BoredomDocument7 pagesMusic and BoredomThomas PattesonNo ratings yet

- An Approach To The Aural Analysis of Emergent Musical FormsDocument25 pagesAn Approach To The Aural Analysis of Emergent Musical Formsmykhos0% (1)

- Dahlhaus Forma MusicalDocument30 pagesDahlhaus Forma MusicalRamon CarnotaNo ratings yet

- LigetiDocument8 pagesLigetimelanocitosNo ratings yet

- Plural Styles, Personal Style - The Music of Thomas AdèsDocument14 pagesPlural Styles, Personal Style - The Music of Thomas AdèsFeiwan Ho100% (1)

- Carter - ConsideringDocument4 pagesCarter - ConsideringP ZNo ratings yet

- Harrison Birtwistle (AGP88)Document1 pageHarrison Birtwistle (AGP88)papilongreeneyeNo ratings yet

- Metamorphosen Beat Furrer An Der HochschDocument3 pagesMetamorphosen Beat Furrer An Der HochschLolo loleNo ratings yet

- Boccherini Six Guitar Quintets MSDocument138 pagesBoccherini Six Guitar Quintets MSclementecolling100% (1)

- Adjectives in Text ProductionDocument68 pagesAdjectives in Text ProductionclementecollingNo ratings yet

- Abel Carlevaro in The History of GuitarDocument12 pagesAbel Carlevaro in The History of GuitarclementecollingNo ratings yet

- Bernard - Bartok Zones of Impingement 3-34music Theory Spectr-2003Document32 pagesBernard - Bartok Zones of Impingement 3-34music Theory Spectr-2003clementecollingNo ratings yet

- Bernard - Audible Music (Ligeti)Document31 pagesBernard - Audible Music (Ligeti)clementecolling100% (1)

- Albert de Rippe Lute TabulaturesDocument65 pagesAlbert de Rippe Lute Tabulaturesclementecolling100% (1)

- Chinese MusicDocument17 pagesChinese MusicApril Reyes Matias100% (1)

- LIL DARLIN Hendricks LyricsDocument1 pageLIL DARLIN Hendricks LyricsriccardomarcolombardNo ratings yet

- Musical Instruments (Turkey)Document4 pagesMusical Instruments (Turkey)Dimitris DimitriadisNo ratings yet

- Week 6: Physical Education and Health 3 (PEDH-121)Document19 pagesWeek 6: Physical Education and Health 3 (PEDH-121)yagamiNo ratings yet

- Lista de Librerias, Presets, Vsts y Mas (Audio)Document15 pagesLista de Librerias, Presets, Vsts y Mas (Audio)Camilo AmayaNo ratings yet

- The Roots and Impact of African American Blues MusicDocument8 pagesThe Roots and Impact of African American Blues MusicMax ChuangNo ratings yet

- Kangarudiments: Art BernsteinDocument6 pagesKangarudiments: Art BernsteinMonta TupčijenkoNo ratings yet

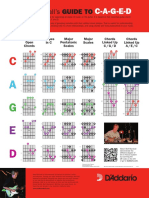

- Dapo Dp0040 Caged System 46246Document1 pageDapo Dp0040 Caged System 46246JP PretoriusNo ratings yet

- CAN'T GET MY EYES OFF YOU - Ukulele Chord ChartDocument1 pageCAN'T GET MY EYES OFF YOU - Ukulele Chord ChartmodelthroughitNo ratings yet

- Electric Elevation Paul Davids - Complete SongbookDocument30 pagesElectric Elevation Paul Davids - Complete SongbookpakrasisNo ratings yet

- Program NotesDocument5 pagesProgram Notesapi-334651370No ratings yet

- Keko Yoma Dossier 2010 EnglishDocument14 pagesKeko Yoma Dossier 2010 EnglishRenato Pizarro Osses100% (1)

- The Old and New Tunes Jazz Piano Adult Beginner Practice Guide - Deborah SacharoffDocument69 pagesThe Old and New Tunes Jazz Piano Adult Beginner Practice Guide - Deborah Sacharofffunkycow117100% (6)

- Helena - MCR Guitar Tab PDFDocument23 pagesHelena - MCR Guitar Tab PDFmatic tokoNo ratings yet

- Jazz Mixing With WavesDocument9 pagesJazz Mixing With WavesMihail Dimitrov0% (1)

- AllText PDFDocument9 pagesAllText PDFRadamésPazNo ratings yet

- HindemithDocument18 pagesHindemithMichael Cotten100% (1)

- Vito Serial NumbersDocument1 pageVito Serial NumbersScottDT1No ratings yet

- GRP5 Sbac1b-Pe2Document5 pagesGRP5 Sbac1b-Pe2Remir Alfred QuianNo ratings yet

- Style and Period - ClassicalDocument1 pageStyle and Period - ClassicalAlice DettmarNo ratings yet

- O Rosto de Cristo - Alto Sax 1Document1 pageO Rosto de Cristo - Alto Sax 1Matheus Domingues Borges100% (1)

- MAPEH 9 (Music) q1Document37 pagesMAPEH 9 (Music) q1Marife SaganaNo ratings yet

- Sal 12Document2 pagesSal 12Yildizhan AYDEMİRNo ratings yet

- Claude BalbastreDocument4 pagesClaude BalbastreDiana GhiusNo ratings yet

- The Modern HarpDocument5 pagesThe Modern HarpSaharAbdelRahmanNo ratings yet

- Composition, My Personal Approach Alan Belkin MusicDocument2 pagesComposition, My Personal Approach Alan Belkin MusicleandroniedbalskiNo ratings yet

- GP Vanilla IceDocument17 pagesGP Vanilla IceRonald MoelkerNo ratings yet

- LookToTheSky (A C Jobim)Document1 pageLookToTheSky (A C Jobim)John SurmanNo ratings yet