Writing The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology Project

Writing The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology Project

Uploaded by

nurainCopyright:

Available Formats

Writing The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology Project

Writing The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology Project

Uploaded by

nurainOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Writing The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology Project

Writing The Proposal For A Qualitative Research Methodology Project

Uploaded by

nurainCopyright:

Available Formats

ARTICLE

10.1177/1049732303255474

QUALITATIVE

Sandelowski,

Barroso

HEALTH

/ WRITING

RESEARCH

A QUALITATIVE

/ July 2003 PROPOSAL

Writing the Proposal for a Qualitative Research

Methodology Project

Margarete Sandelowski

Julie Barroso

Writing the proposal for a qualitative research methodology study is a double challenge

because of the emergent nature of qualitative research design and because a methodology

study entails describing a process to produce a process. How the authors addressed this challenge is shown in the annotated text of the grant proposalAnalytic Techniques for Qualitative Metasynthesisfunded by the National Institute of Nursing Research. Appealing

qualitative research proposals adhere to principles that engage writers and readers in an

informative and mutually respectful interaction.

Keywords: qualitative research; proposal writing; qualitative metasynthesis

riting the proposal for a qualitative study is a challenge because of the emergent nature of qualitative research design (Sandelowski, Davis, & Harris,

1989). Designing studies by conducting themas opposed to conducting studies by

designproposal writers can only anticipate how their studies will proceed. Qualitative research proposals are thus exercises in imaginative rehearsal. When the proposed study is directed toward developing qualitative methods, the challenge

becomes even greater as such a proposal entails the rehearsal of a process to develop

a process. In a methodology study, process is outcome.

In this article, we reproduce1 and annotate (in italics) the text of a grant proposalAnalytic Techniques for Qualitative Metasynthesis that we submitted

in 1999 to the National Institute of Nursing Research (NINR), National Institutes of

Health (NIH). This project received a priority score of 110 (0.6 percentile) and was

funded in June 2000 to run for 5 years. Our annotated comments are intended both

to be instructive and to serve as explanations for why we made certain statements or

placed these statements where we did. Because this proposal was a resubmission,

we then offer suggestions for revising and resubmitting proposals that initially do

not receive scores high enough for funding. We conclude by offering what we think

of as principles for writing effective qualitative proposals.

AUTHORSNOTE: The study featured in this article is supported by Grants NR04907 (6/1/00-2/28/05)

and NR04907S (6/1/03-2/28/05) from the National Institute of Nursing Research, National Institutes of

Health. Please address all correspondence to M. Sandelowski, 7460 Carrington Hall, Chapel Hill, NC

27599, USA.

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH, Vol. 13 No. 6, July 2003 781-820

DOI: 10.1177/1049732303255474

2003 Sage Publications

781

782

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / July 2003

THE PROPOSAL: ANALYTIC TECHNIQUES

FOR QUALITATIVE METASYNTHESIS

Specific Aims

The immediate aim of the proposed study is to develop the analytic and interpretive

techniques to conduct qualitative metasynthesis projects, using research on women

with HIV/AIDS as the method case. In sections on aims, writers should state the aims

first; reviewers should not have to wait for them. Although all qualitative research, narrative integrations of quantitative research, and broad overviews of knowledge

fields entail synthesis, or some combination of two or more entities, qualitative

metasynthesis is a distinctive category of synthesis in which the findings from completed qualitative studies in a target area are formally combined. Qualitative

metasynthesis constitutes a specific kind of data-driven research that is analogous

to quantitative meta-analysis in its intent systematically, as opposed to

impressionistically (Fawcett, 1999), to combine the findings in a target domain of

scientific research. These last two statements constitute an example of what we call strategic disarmament, which entails anticipating likely areas of controversy, debate, or differences of opinion. Because the word synthesis is used in a variety of ways to refer to a variety

of entities, differentiating right away the kind of synthesis that was the focus of our proposal

was critical. These statements are also in response to a previous review in which our take on

synthesis was not sufficiently clear. We have chosen the area of women with HIV/AIDS

as our method case because a sufficient number of qualitative studies exists here to

warrant metasynthesis, and it is a field of great significance to womens health and

nursing practice. We were, in fact, funded as an HIV/AIDS project. HIV infection is a

priority area of Healthy People 2000.2 The development of techniques to improve

the analysis, interpretation, and use of data and, specifically, to integrate evidence

from qualitative research is also a goal of the National Institutes of Health. Referring

to research, practice, or policy priorities or initiatives of various national agencies helps to

underscore the significance of study aims. We specifically staged our application as a

response to the NIH Program Announcement concerning Methodology and Measurement

in the Behavioral and Social Sciences.

Qualitative research is on the crest of a wave (Morse, 1994, p. 139) and has

become immensely popular in the practice disciplines. The proliferation of qualitative studies on various aspects of health, illness, and life transitionsphenomena of

key interest to nurseshas been unprecedented. Despite its new prominence in the

practice disciplines, however, concerns remain about the ability of qualitative

research to resolve real-world problems. A key factor accounting for the perceived lack of usefulness of qualitative research is the relative absence of efforts to

integrate, synthesize, or otherwise put together the findings from this research.

Having stated the aim of the proposed study, we introduce here the problem that generated it

and the significance of the problem. We worked backward from the aims to the research problem and its significance.

Qualitative research findings contain information about the subtleties and complexities of human responses to disease and its treatment that is essential to the construction of effective and developmentally and culturally sensitive interventions.

However, for qualitative research findings to matter, they must be presented in a

Sandelowski, Barroso / WRITING A QUALITATIVE PROPOSAL

783

form that is assimilable into the personal modes of knowing . . . valuing (Noblit,

1984, p. 95) and/or doing of potential users, including researchers and practitioners. Although a few laudable efforts have been made to integrate the findings of

qualitative health research (e.g., Jensen & Allen, 1994; Paterson, Thorne, & Dewis,

1998), qualitative metasynthesis as method remains largely undeveloped.

Moreover, calls for more research in a target domain do not necessarily entail

the collection of yet more data but, rather, might require the insightful mining of

data already collected. A new moral consciousness has emerged about inviting persons, already vulnerable by virtue of their health conditions or life circumstances, to

participate in yet more studies to obtain information we already have (e.g., Thorne,

1997). Recruitment of persons into qualitative studies, in particular, cannot be justified by the benefits of such participation alone (e.g., Hutchinson, Wilson, & Wilson,

1994). Qualitative metasynthesis is such a mining project, that is, an important avenue toward the development of knowledge (especially the soft knowledge often

eluding measurement) and an exemplar of clinical scholarship (Diers, 1995) equal

to primary research in its potential to improve health research instrumentation

and health care practices. In the preceding paragraph, we emphasized the significance of

the problem.

Here, we return to the aims and flesh them out with specific objectives. Accordingly,

we propose to develop a systematic, comprehensive, usable, and communicable

research protocol for conducting qualitative metasynthesis projects in any healthrelated field. To accomplish this objective, we will offer solutions to problems that

qualitative metasynthesis raises, including how to (a) define the limits of a synthesis

project, (b) group studies for comparison and combination, (c) evaluate the quality

of studies, (d) determine the true as opposed to surface topical and methodological comparability of studies, (e) choose and apply the analytic techniques most

appropriate for integrating the findings from a particular set of studies, and

(f) select and use the re-presentational form for the metasynthesis product best

suited to different consumers of qualitative research, including researchers and

practitioners. We will also provide a metasynthesis of research findings in the area

of women with and in a second area of research to test the metasynthesis protocol

we develop. The test case will involve research on couples undergoing prenatal

testing.

The outcomes of the proposed project will therefore include both a product (the

metasyntheses themselves) and a process (a research protocol to conduct qualitative metasynthesis projects). Our long-term goals are to advance substantive

knowledge in the field of HIV/AIDS and prenatal diagnostic technology and to

advance qualitative methodology. The project will enhance the analytic power of

qualitative research findings so that the understandings of human experience contained in them can serve as a basis for improved research and health care practices.

In this first section of the proposal, we adopted the following logic: immediate aim

significance of aim problem significance of problem aim with objectives outcome

and long-term aim. By the end of this section, reviewers should have been offered what

amounts to an executive summary of the proposed study emphasizing its significance. The

significance of establishing significance cannot be overestimated. A research proposal low in

significance, albeit high in technical perfection, is not likely to be funded.

784

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / July 2003

Background and Significance

In the following paragraphs, we review the literature (accurate as of 1999) or develop ideas

previously introduced in the Aims section. A good literature review has a clearly defined

logic in the service of only one goal: making the case for the proposed study. We followed a

largely gap logic, in that our review was oriented to showing what was still missing in the

domain of research integration and the reasons for this gap. We have described other logics

for the literature review elsewhere (Sandelowski & Barroso, 2002). Over the past two

decades, largely in response to Glasss (1976) work in the area of meta-analysis, a

surge of efforts has been directed toward research integration, especially in the

health/medicine domain (Bausell, Li, Gau, & Soeken, 1995; Kavale, 1995). Although

research integrations were promoted and conducted prior to this time, the proliferation of empirical research in the behavioral and social sciences and science-based

practice disciplines has made ever more urgent the need for research integrations

both to reduce information anxiety (Harrison, 1996, p. 224) and to facilitate better

use of research findings (Cook, Mulrow, & Haynes, 1997). Not only do hundreds of

published reports of quantitative research integrations now exist, major collaborative efforts have also been directed toward such integrations, including the Sigma

Theta Tau Online Journal of Knowledge Synthesis and the Cochrane Collaboration to

synthesize the results of randomized controlled trials of health/medical practices

and treatments (Chalmers, 1993). In this paragraph, we have set the scene.

We now move quickly to the point: detailing the problem previously introduced in the

Aims section. Conspicuously absent from this thriving research integration scene are

efforts to integrate the findings of qualitative research. This absence is all the more

remarkable as few other research approaches now rival the interest shown in qualitative research by scholars in many different disciplines and fields of study. Since

the 1980s, at least 1,000 qualitative studies have been conducted in the health field

alone, which have been disseminated both in research journals once almost exclusively devoted to quantitative research reports and in media newly created to disseminate qualitative work (e.g., the interdisciplinary journal Qualitative Health

Research and the annual international Qualitative Health Research Conference).

These studies contain findings about a diverse range of health issues, including,

most notably, personal and cultural constructions of disease, prevention, and risk;

living with and managing the effects (including the treatment effects) of an array of

chronic conditions; and decision making around and responses to beginning- and

end-of-life technological interventions. Despite its new prominence, however, the

false notions still prevail that qualitative research is only a prelude to real

research, and that qualitative findings are ungeneralizable, noncumulative, and,

ultimately, irrelevant in the real world of clinical practice (Sandelowski, 1997).

The paradox is that qualitative research is conducted in the real worldthat is,

not in artificially controlled and/or manipulated conditionsyet is seen as not

applicable in that world. This perceived lack of relevance and utility has potentially

serious consequences for the use of qualitative methods and findings and, therefore, for nursing and other health-related practice fields.

One recent response to the utility problem has been the call for qualitative

metasynthesis. Qualitative metasynthesisas it is conceived in the few articles on

this subject (with this phrase, we reinforce how little there is on qualitative metasynthesis

and thus the significance of the proposed study)is a form of metastudy, that is, study of

the processes and results of previous studies in a target domain that moves beyond

Sandelowski, Barroso / WRITING A QUALITATIVE PROPOSAL

785

those studies to situate historically, define for the present, and chart future directions in that domain. In metastudies, the researcher seeks not only to combine the

results of previous studies but also to reflect on them (Zhao, 1991, pp. 377-378). Like

phenomenology, ethnography, and grounded theory, the term qualitative metasynthesis

refers both to an interpretive product and to the analytic processes by which the

findings of studies are aggregated, integrated, summarized, or otherwise put

together (Estabrooks, Field, & Morse, 1994; Jensen & Allen, 1996; Kearney, 1998a;

Noblit & Hare, 1988; Sandelowski, Docherty, & Emden, 1997; Schrieber, Crooks, &

Stern, 1997). Although it can be considered an analogue to meta-analysis (Glass,

McGaw, & Smith, 1981) in that there is a shared interest in synthesizing empirical

studies (Noblit & Hare, 1988, p. 10) and a shared desire to use a systematic, comprehensive, and communicable approach to research integration, qualitative

metasynthesis is not about averaging or reducing findings to a common metric

(Wolf, 1986, p. 33). We again use the device of contrasts to clarify our focus and to differentiate qualitative metasynthesis from other entities reviewers might view (and, in the case of

one of our reviewers, did view) as similar to it. Instead, the aim of qualitative

metasynthesis is to create larger interpretive renderings of all of the studies examined in a target domain that remain faithful to the interpretive rendering in each

particular study. A prime directive for qualitative researchers, no matter what their

method or research purpose, is to preserve the integrity of each sampling unit or

case (Sandelowski, 1996). In qualitative metasynthesis projects, this prime directive

entails preserving the integrity of and the richness of findings in each individual

study.

Yet this prime directive is likely a major reason why few qualitative metasyntheses have been conducted. Indeed, by virtue of their emphasis on case-bound or

idiographic knowledge, qualitative studies seem to resist summing up (Light &

Pillemer, 1984). Efforts to summarize qualitative findings appear to undermine the

function and provenance of cases (Davis, 1991, p. 12) and to sacrifice the vitality,

viscerality, and vicariism of the human experiences re-presented in the original

studies. The very emphasis in qualitative research on the complexities and contradictions of N = 1 experiences (Eisner, 1991, p. 197) seems to preclude adding these

experiences up. Moreover, the sheer diversity of qualitative research practices is

another reason why so few efforts to synthesize qualitative findings have been

attempted. Qualitative researchers have vastly different disciplinary, philosophical,

theoretical, social, political, and ethical commitments, and they often have very different views of how to execute ostensibly the same kind of qualitative research.

Neopositivists and constructivists, feminists and Marxists, and nurses, educators,

and anthropologists conduct grounded theory, phenomenologic, ethnographic,

and narrative studies. Furthermore, given the wide variety of re-presentation styles

for disseminating qualitative research, even finding the findings can be a daunting

challenge. We are showing here that we know that not all qualitative researchers agree that

metasynthesis is warranted, feasible, or congruent with a qualitative attitude.

Yet, qualitative research is endangered by the failure to sum it up. By using the

yet device, we quickly move here to reinstate the need to address the problem of resistance

to qualitative research integration. We show here a yes-but logic, that is, yes, we support the

legitimacy of the arguments of those who might disagree with what we intend, but we also

affirm the need to try. A recurring concern is that qualitative researchers are engaged

in a cottage industry: working in isolation from each other, producing one-shot

research (Estabrooks et al., 1994, p. 510) and, therefore, eternally reinventing the

786

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / July 2003

wheel. Early in the history of grounded theory, Glaser and Strauss (1971) warned

that continued failure to link local grounded theories into formal theories (a type of

qualitative metasynthesis) would relegate the findings of individual studies to little islands of knowledge, separated from each other and doomed ultimately never

to be visited (p. 181). Qualitative metasynthesis is increasingly seen as essential to

reaching higher analytic goals and also to enhancing the generalizability of qualitative research. Schofield (1990) viewed qualitative metasyntheses as cross-case generalizations created from the case-bound generalizations in individual studies. We

wanted reviewers to have a sense of a debate here and what side we were, and had to be, on

to propose this study.

Examples of Qualitative Metasyntheses

Two kinds of interpretive syntheses of findings from qualitative studies have been

attempted. One involves the integration of findings from multiple analytic paths

pursued within one program of research by the same investigator(s). An example is

the synthesis work Morse and her colleagues conducted in her program of research

on chronic illness (e.g., Morse, 1997a; Morse & Johnson, 1991). Another example is

the Field and Marck (1994) anthology, in which the faculty supervisors of six doctoral dissertations used uncertainty as the concept around which to organize findings about motherhood from these studies. Athird example is one of our own efforts

(Sandelowski, 1995) to synthesize the findings of different aspects of the transition

to parenthood of infertile couples. (This study is described in more detail in the Preliminary Studies section.) In all three of these studies, the investigators used

grounded theory techniques to produce larger conceptual renderings of substantive theories developed in their primary studies. In this kind of synthesis effort,

synthesists maintain the same relationship to data as they had in their primary

research, having created both data sets (the primary data and the studies derived

from these data). Moreover, they have direct access to the primary data for the synthesis.

A second kind of effort, and the one we will focus on in this project, involves the

interpretive synthesis of qualitative findings across studies conducted by different

investigators. Kearney (1998b) used grounded theory methods to synthesize the

findings from 10 studies on womens addiction recovery. The remaining efforts

were ostensibly based on the Noblit and Hare (1988) work, which involved three

kinds of translations of individual ethnographies into each other to produce three

metaethnographies in the field of education. Jensen and Allen (1994) synthesized

the findings from 112 studies on wellness-illness; Paterson et al. (1998) produced a

metaethnography of living with diabetes from 43 studies; Sherwood (1997) synthesized 16 qualitative studies on caring to produce a composite description (p. 39)

and therapeutic model (p. 40) of caring; and Barroso (a co-principal investigator

in the proposed project) and Powell-Cope (1998) synthesized the findings from 21

studies on living with HIV/AIDS. (This study is described in more detail in the Preliminary Studies section.) In this kind of synthesis effort, where the focus of analysis

is studies in a topical domain conducted by a range of investigators, synthesists are

far removed from, and typically have no access to, the primary data on which these

studies were based. (An exception here is when synthesists include one of their own

studies, as, for example, Noblit, Kearney, and Sherwood did in conducting their

projects.) Accordingly, their data are composed solely of what is on the pages of a

Sandelowski, Barroso / WRITING A QUALITATIVE PROPOSAL

787

research report, which might be influenced by limitations in the research enterprise

itself and/or imposed by the publication venue.

These efforts to synthesize the findings of qualitative data are valuable for the

methodological direction they provide but, more important, also for the proposed

project, for the continuing methodological problems they illuminate and dramatize. For example, although Jensen and Allen (1994) cited Noblit and Hare (1988) as

their metasynthesis method source, the techniques they used, the product they generated, and the research purpose they stated were different from those of Noblit and

Hare. Jensen and Allens (1994) purpose was to inductively develop a theory of

wellness-illness from the commonalities among individual representations of

health and disease (p. 350). Noblit and Hare espoused interest not in developing

overarching generalizations (p. 25) but, rather, in determining how studies were

related to each other. Indeed, they argued against the notion of synthesisas accumulation or aggregationafter describing a failed effort at just such an aggregative

synthesis of several ethnographies on school desegregation. Instead, they proposed, studies can be judged in relation to each other as (a) comparable and, therefore, subject to reciprocal translation; (b) refuting each other; or (c) representing a

line of argument (p. 36). Moreover, they proposed their methods to fit explicitly

ethnographic studies, thereby calling into question the applicability of these methods to the kinds of studies Jensen and Allen reviewed and, therefore, to the kinds of

studies typically conducted in nursing and other health-related disciplines. Jensen

and Allen groupedby method112 studies (an enormous sample in qualitative

research) on wellness-illness (a concept incorporating many diverse dimensions

not explored in their study) reported in journal articles, dissertations, and theses.

They then used these same methods to synthesize the findings in each method

group (e.g., grounded theory to synthesize the findings of grounded theory studies,

phenomenology to synthesize the findings of phenomenology studies). Their final

product was reportedly one metasynthesis of wellness-illness composed of a blend

of conceptual and phenomenological description. Noblit and Hare produced one

comparable metaethnography from the findings of two published book-length

studies (one of which was a study Noblit had himself conducted), two

refutational syntheses of the findings from two book-length studies each, and one

line-of-argument synthesis of the findings from six studies (also including one

Noblit had conducted) published in one anthology on school desegregation. The

Paterson et al. (1998) study shows a similarly distant relationship to the Noblit and

Hare work but a close relationship to grounded theory work, despite the investigators naming Noblit and Hare as a method source. With references to the Jensen and

Allen and Noblit and Hare works, the Sherwood (1997) study is the most impressionistic of all the qualitative metasyntheses we reviewed, showing a greater similarity to a conventional narrative review of literature than to systematic integration

of findings across studies.

All of these studies are exciting efforts but lack sufficient communicable detail

concerning how they achieved their integrations, and none explicitly addressed or

showed how key dilemmas in conducting qualitative research syntheses were

resolved. Our intention here was to present the work of other scholars positively and

respectfully while also pointing out the gaps that our proposed study was designed to

address. Our two rules in presenting the work of others are (a) never to use the word fail in

describing what other scholars merely did not do (as this would only be a reflection of what

we wanted them to do, or thought they might have done, and not a failure on their part) and

788

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / July 2003

(b) describe accurately what they did do. The dual imperatives to give other scholars their due

and to advance scholarship are somewhat antithetical, as finding something that requires

further researching is the sine qua non of the academic enterprise. These imperatives thus

require a delicate balancing act, as the continuation of this enterprise depends on scholars

finding gaps, errors, or inconsistencies in existing scholarship. Some of these dilemmas

are comparable to those still unresolved in quantitative research integrations, for

example, deciding whether and how to use quality as a criterion for inclusion of

studies in the bibliographic sample, and whether and how to integrate heterogeneous studies (e.g., Cook, Cooper, et al., 1992; Lynn, 1989; Mulrow, Langhorne, &

Grimshaw, 1997). Dilemmas distinctive to qualitative research integrations include

separating data from the interpretation of those data, preserving the integrity of

each study, and avoiding immersion in so much detail that no usable synthesis is

produced. Moreover, qualitative metasynthesis entails resolving persistent dilemmas in qualitative research itself, most notably, the problems of determining what

constitutes a trustworthy study and the influence of method on findings. Because

the proposed project is directed toward developing and explicating means to

resolve these and other dilemmas in conducting and creating qualitative

metasyntheses, we will address them in detail in the section on Research Design and

Methods. Here is where we begin to depart from standard procedure because we are proposing a study of method, and so we alert reviewers to this change. Generally, writers should

avoid presentations in which readers are constantly referred to what was said previously or

what has yet to be said later. Too many references to discussions that took place previously

or that will take place below suggest that writers have not placed material in the right

order in the first place. Writers might thereby be forced to repeat material unnecessarily and

thus to consume space better used for other components of their proposal.

Women With HIV/AIDS as a Method Case

We have chosen research on women with HIV infection as our method case because

of the many and complex health care needs these women have and because a sufficient number of qualitative studies containing information important to these

womens health has been conducted to warrant metasynthesis. No integrations of

these findings have been conducted. In 1991, Smeltzer and Whipple published an

article summarizing the state of the science on women with HIV infection. Since

then, researchers have published several reviews of the literature, all of which have

focused on the epidemiological profile of HIV infection and a variety of medical

problems (e.g., Burger & Weiser, 1997; Cohen, 1997; Fowler et al., 1997; Klirsfeld,

1998). Most recently, Sowell, Moneyham, and Aranda-Naranjo (1999) summarized

the major clinical, social, and psychological issues facing women with AIDS,

emphasizing the many differences between men and women.

Women now represent the fastest growing segment of persons infected with

HIV, with up to 160,000 adolescent and adult females living with HIV infection in

the United States alone (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], 1999;

Cohen, 1997; Fowler, Melnick, & Mathieson, 1997). Between 1981 and 1997, the percentage of seropositive women increased from nearly zero to almost 20% of all new

cases (Cohen, 1997; Klirsfeld, 1998). As of December 1998, there were 109,311

reported cases of AIDS in women, which represents only a small proportion of all

women infected with the virus; this figure does not include those infected women

who have not progressed to AIDS. Of this number, 61,874 women are African

Sandelowski, Barroso / WRITING A QUALITATIVE PROPOSAL

789

American, 21,937 are Hispanic, and 24,456 are White. The remaining women are in

other ethnic/racial categories, including Native American. The largest numbers of

AIDS cases in women are in the 30- to 39-year-old age group. HIV/AIDS was the

fourth leading cause of death among women in the United States between 25 and 44

and the leading cause of death among African American women in this age group

(CDC, 1999). AIDS disproportionately affects minority women, with women of

color making up approximately 75% of AIDS cases in women in the United States

(Cohen, 1997; Gaskins, 1997; Klirsfeld, 1998; Stein & Hanna, 1997). The typical

woman with HIV is a young, poor, minority woman in her childbearing years

(Russell & Smith, 1998; Sowell et al., 1999).

Since 1993, and as a consequence of the increasing rate of HIV infection in

women, there has been a proliferation of qualitative studies addressing womens

experiences as infected individuals. Prior to 1993, qualitative research that included

women was devoted largely to their roles as mothers of seropositive children or as

vectors of transmission. Even when researchers began to seek information from

women about their experiences with HIV, they combined it with information

obtained from men. (This is why women were not the focus of study in the research

integration of findings on HIV/AIDS described below in the Preliminary Studies

section.) We wanted to ensure that reviewers did not think a metasynthesis of qualitative

studies on HIV-positive women already existed and that we were simply repeating a previous study. Scholars in womens/gender studies and in womens health have shown

the importance of treating gender as a key variable differentiating experience (e.g.,

Fogel & Woods, 1995; Harding, 1991). Indeed, there is evidence that sex/gender is a

critical variable in understanding HIV/AIDS disease. For example, the findings

from a recent study suggest biological differences in HIV viral load between men

and women, with women developing AIDS at a lower viral load (after adjustment

for CD4 count) than men (Farzadegan et al., 1998). Women bear the greater burden

in the areas of reproduction, child care, and other family functions. Seropositive

women must make critical and even agonizing decisions about childbearing, abortion, sterilization, and child care (Arras, 1990; Levine & Dubler, 1990; Sowell et al.,

1999). Their parenting and other family responsibilities often preclude seeking

health care in a timely fashion. Because they are often disempowered in their relationships with male partners, women might find it more difficult to engage in practices to prevent HIV transmission. Heterosexual relations are the most rapidly

increasing mode of transmission of HIV in women, with most women infected in

this way reporting contact with male partners who inject drugs (CDC, 1999; Cohen,

1997). The imbalance of power between women and men often limits womens ability to negotiate condom use (Bedimo, Bennett, Kissinger, & Clark, 1998; Bedimo,

Bessinger, & Kissinger, 1998; Gaskins, 1997; Walmsley, 1998). Increasingly, women

with HIV infection are unaware of their male partners exposure to or risk for HIV

infection (Cohen, 1997; Fowler et al., 1997). Women who are abused are often prevented from practicing safe sex (Gaskins, 1997). Among 2,058 seropositive

women in the Womens Interagency HIV Study (Barkan et al., 1998), 66% reported

abuse by their partners. Violence has also emerged as a key variable in other studies

of women with HIV (e.g., Bedimo, Bennett, et al., 1998; Sowell et al.,1999). Finally,

some investigators have suggested that stigma might be differently and/or more

intensely experienced among HIV-infected women than men (Leenerts, 1998;

Raveis, Siegel, & Gorey, 1998).

790

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / July 2003

Qualitative research findings are now available that contain information not

captured in biomedical and epidemiological studies on such topics as stigma and

disclosure, barriers to health care, symptom management, and alterations in

parenting. Bedimo, Bessinger, and Kissinger (1998) observed that although they

had obtained important facts about womens reproductive decision making from

their chart review, they had failed to learn anything about the meaning of those facts

to women themselves. At a recent meeting of the Society for Medical Anthropology,

researchers reportedly noted how little impact qualitative studies had on AIDS

research and prevention agendas (Swanson et al., 1997, p. 256). The proposed project will address these problems by creating a synthesis of findings from qualitative

research on women with HIV/AIDS that can be used for research and in practice.

What we intended here was to establish the significance of choosing the studies for the

method case, which is comparable to defending the choice of a particular sample.

Significance for Research and Practice

The larger significance of this project lies in the potential for qualitative research

integrations to enhance the practical value of qualitative research (Thorne, 1997),

that is, to serve as a creative bridge (Swanson, Durham, & Albright, 1997, p. 256)

between qualitative research findings and practice. Qualitative research is still

largely viewed as contributing primarily to enlightenment, something to the conceptual use of knowledge, and virtually nothing at all to the instrumental use of

knowledge. Indeed, contemporary models of research use emphasize quantitative

research findings (Cohen & Saunders, 1996; Estabrooks, 1997; Sandelowski, 1997;

Swanson et al., 1997). Moreover, contemporary notions of evidence-based practice,

with their virtually exclusive emphasis on randomized and controlled clinical trials

as the gold standard in methods, discount qualitative findings as evidence

(Estabrooks, 1999).

The proposed project will enhance the actionability of knowledge produced by

qualitative research by developing a user-friendly procedure for conducting qualitative research integrations that can stand as evidence for practice. A key deterrent

to researchers attempting qualitative metasynthesis projects is the virtual lack of

direction on how to conduct them. A persistent problem impeding practitioners

use of research findings is that they are presented in forms that are incomprehensible and irrelevant to practitioners (Funk, Tornquist, & Champagne, 1995).

The findings from the proposed project will also contribute to the actionability

of qualitative research by enhancing the generalizability of study findings. As

Sandelowski (1996, 1997) summarized it, in quantitative research, emphasis is

placed on nomothetic generalizations, or the formal knowledge toward which random sampling and assignment are directed. The objective is to enhance the external

validity of findings by permitting generalizations to be made from representative

samples to populations. In contrast, in qualitative research, the emphasis is placed

on idiographic or naturalistic generalizations, or the knowledge derived from and

about cases. Nursing and medical practice depend on both kinds of generalizations,

as practitioners must fit formal knowledge to the particulars of cases. Qualitative

metasynthesis is a means to enhance the analytic power of idiographic knowledge,

as it entails the intensive case-oriented study of target phenomena in larger and

more varied samples than are typically the rule in any one qualitative study. For

example, Kearney (1998b) combined the findings of 10 studies in the area of

Sandelowski, Barroso / WRITING A QUALITATIVE PROPOSAL

791

womens substance abuse recovery, which involved more than 200 women in different cultural, racial, historical, and geographic circumstances. The power (Kearney, 1998a, p. 182) of this sample size and configuration lies in the ability not to draw

statistical inferences but, rather, to draw case-bound generalizations concerning a

target phenomenon across a range of cases. The practical value of this work lies in

making the most of the idiographic knowledge that qualitative research distinctively yields. Knowledge of the particular is critical to offset the frequent failure of

formal generalizations to fit the individual case. The development of valid instruments to measure health conditions and appropriate interventions to improve them

depend on just this kind of knowledge.

Finally, the findings from the proposed project will enhance the applicability of

qualitative findings directly to practice. A key deterrent to the use of qualitative

findings is the persistent notion that findings from qualitative studies cannot be

applied directly in practice without quantitative testing. This idea reprises the false

notion that qualitative research is always incomplete by itself (Morse, 1996). Moreover, it permits the idea of testing to remain appropriated exclusively for quantitative research. Testing is a sociocultural and linguistic concept and practice that does

not belong exclusively to the quantitative domain, as this word has meaning

beyond the mathematized definition it has there. Indeed, qualitative findings are by

definition findings validated against experience. Grounded theory, for example,

isby both definition and purposetheory grounded in and tested against human

experience. There is no more justification for applying tested nomothetic knowledge that often fails, or must be adapted, to fit the individual case than there is for

applying idiographic knowledge directly to a case. All findings, whether quantitatively or qualitatively generated and tested, must ultimately be tested in practice

with individual cases to ensure their pragmatic and ethical validity (Kvale, 1995).

The proposed project will provide a means to further this goal and to offset the current trend toward reducing our understanding of evidence to findings only from

experiments (Colyer & Kamath, 1999; French, 1999). Yet the findings from this project will likely also clarify how qualitative evidence can be used to improve the evidence from experiments, that is, to improve the design sensitivity and validity of

clinical trials (Lipsey, 1990; Sidani & Braden, 1998). In the preceding paragraph, we confronted the thorny issues of validity and generalizability by countering the quantitative

appropriation of the word testing.

In the previous section, we brought home the significance of the likely products of the

proposed study. Again, making the case for the significance of research problems, research

aims, and research outcomes is a defining attribute of a successful proposal. Reviewers are

more likely to forgive technical flaws in design if an excellent case is made for significance in

these three areas.

Preliminary Studies

The proposed project builds on metasynthesis studies the co-principal investigators

have conducted previously. Sandelowski (1995) has published a theoretical synthesis of findings generated from multiple analytic paths pursued in her study of the

transition to parenthood of infertile couples. (A copy of this article is in Appendix A.

Appendix A is not reproduced here.) This work is in the category of metasynthesis projects, characterized by the integration of findings from multiple analytic paths pur-

792

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / July 2003

sued within the synthesists own program of research. The synthesist maintains

direct access to the data generating the findings and can easily answer questions

about the findings and the procedures that produced them. Moreover, the synthesist here does not have to deal with issues related to bibliographic retrieval.

Sandelowski used traditional grounded theory techniques to find a core variable

around which to organize the various findings generated from primary data analysis. This variable was work and, specifically, illness work and biographical

work. She then compared several groups of infertile couples to each other and to a

group of fertile couples to define the overlapping and special work distinctive

to each group. Although this work represents a kind of qualitative metasynthesis, it

did not entail a significant methodological departure from other grounded theory

efforts directed toward creating more abstract and transferable conceptual renderings of phenomena.

In contrast, Barroso and Powell-Cope (a member of the Expert Panel to be

described below) conducted the more difficult kind of qualitative metasynthesis

involving other investigators studies, where the synthesist has no direct access to

the data that generated the findings reported in these studies. (Acopy of the in-press

article reporting the results of this study is located in Appendix A. Appendix A is not

reproduced here; the article was published in 2000.) This is the kind of metasynthesis that

is the target of the proposed project. The focus of the Barroso/Powell-Cope project,

which began in 1996, was living with HIV disease. (As noted previously, women

were not the focus of study here. The participants involved in the studies reviewed

were largely gay men). An exhaustive search of multiple computer databases

showed a large number of qualitative studies had been conducted in this area. The

investigators limited their study to research published in refereed journals, because

they had limited resources with which to conduct this project and the refereed journal venue implied peer review. Accordingly, such important fugitive literature

(Lynn, 1989, p. 302) as doctoral dissertations was not included in their study. They

initially examined 45 English-language articles. The final bibliographic sample for

the metasynthesis included 21 studies consisting of a total of 245 pages of tightly

printed text. Studies were excluded for the following reasons: (a) They were not

qualitative but, rather, only qualitative adjuncts to quantitative studies; (b) qualitative data were analyzed quantitatively; (c) they did not address HIV/AIDS but,

rather, treated related topics, such as patients responses to hospital care; (d) they

consisted of secondary analyses of data collected in another study; and (e) they did

not meet quality standards.

Barroso and Powell-Cope (2000) evaluated quality using Burnss (1989) standards for qualitative research, which include determining whether all of the desired

elements of a research report are present and the extent to which a report meets five

critique standards. Burnss guide remains the most comprehensive guide for evaluating qualitative research. Each of the critique standards consisted of multiple items

the investigators used to score each study. As Burns did not offer a means to score

studies on her critique standards, the investigators had to create a scoring system.

An item was judged to be present, minimally present, or absent. The investigators

decided to include studies if 75% of these criteria were at least partially met. Each

investigator scored half of the studies. Studies deemed unacceptable by one investigator were reviewed by the other investigator, and studies deemed unacceptable by

both investigators were excluded. The investigators also reached consensus on

studies about which they initially disagreed.

Sandelowski, Barroso / WRITING A QUALITATIVE PROPOSAL

793

In doing this work, Barroso and Powell-Cope (2000) were confronted with the

difficulty of applying critique standards to qualitative studies. For example, they

found that studies rarely met the Burns (1989) criteria fully, and they surmised this

was most likely because of publication limitations, that is, a study might have actually met the criteria in practice, but all of the information supporting these criteria

could not be included in the report of the study. Moreover, Barroso and PowellCope began to question whether all of the criteria were equally important to establishing the trustworthiness of the findings. They also questioned the meaning of

some of the criteria themselves. For example, they were uncertain about how to find

evidence for, score, or weigh the adequacy of a researchers self-awareness. Burns

listed inadequate self-awareness as a threat to descriptive vividness (p. 48) In

short, the investigators concluded there was a need to find a standardized, communicable, and useful means of judging the value of qualitative work that could both

(a) serve as a guide for what a qualitative report should include regardless of publication constraints and (b) account for the idiosyncratic ways in which qualitative

research is conducted.

After determining which HIV studies would be included in their study, Barroso

and Powell-Cope (2000) used constant comparison analysis as the major analytic

tool to create the metasynthesis. They acknowledged the Noblit and Hare (1988)

work but had difficulty applying the method described there, which involved analyzing two to six book- or chapter-length ethnographies in education, to their own

study involving multiple article-length studies in the domain of health. They developed a classification system based on findings after discovering that grouping studies by method did not allow them to focus on the findings and their relationships to

each other. They placed findings in a common area of HIV experience, such as dealing with stigma, in separate files. They then sought to develop ways to consolidate

findings in each of these areas, attempting to find metaphors or concepts to grab the

findings and to discern the variations in findings on a target experience. The findings in target experiences were then summarized in narrative form, with a section of

the report devoted to each target experience. Questions were raised in this phase of

the project concerning what to do with findings reported in only one or two studies,

how to use the primary data the original investigators used to support the integration of findings, and what form the metasynthesis product should have. The investigators decided to concentrate on findings reported in the majority of studies, to

use original quotes to support findings, and to present an informational summary

of the metasynthesis findings.

Despite the methodological issues they confronted in conducting this project,

the investigators found that their understanding of living with HIV/AIDS was

enhanced. Indeed, Barroso and Powell-Cope have used the findings from their

metasynthesis in their practice with HIV/AIDS patients as a basis for appraisal and

intervention. For example, they were surprised to find how common the effort to

find meaning in HIV/AIDS was among affected persons. This meta-finding enabled them to think of this effort as a positive outcome of coping toward which

patients strove. The findings of their metasynthesis also heightened their awareness

of the everyday work involved in living with HIV/AIDS and, therefore, of the need

to communicate this to patients. That is, living long and well with HIV/AIDS is not

a part-time job but, rather, requires daily work on the part of patients. The metafinding that social support and human connectedness served as buffers against

social stigma also encouraged Barroso and Powell-Cope to discuss more fully with

794

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / July 2003

their patients the potential value of telling their loved ones about their infection.

Finally, the meta-finding of shattered meaning led them to become more aware of

patients who might require assistance to find meaning in HIV/AIDS. The net

effect of their metasynthesis was to confirm what they had intuited by working with

patients with HIV/AIDS but on which they had been hesitant to act.

In summary, our preliminary efforts confirmed our view of the potential value

for practice of conducting qualitative metasyntheses but also forced us to revisit

persistent issues in qualitative research related to quality and communicability of

procedural and analytic moves. Moreover, they raised questions about how to disentangle methodological orientation and data from findings to understand their

relationships to and mutual influence on each other and how to make judgments

about the practice of qualitative research from the reports of qualitative research.

We plan to offer answers to these questions in the proposed project.

Our goal here was not only to show that we had already engaged the research problem

but also to specify and discuss only those findings that served as the immediate basis for the

proposed study. What we found concerning infertility and HIV was not the point here, so

those findings are not featured. Rather, we feature those findings concerning methods, which

is congruent with the method objectives of the proposed project.

Bibliographic Retrieval for the Proposed Project

In specific preparation for the proposed project, 1,500 abstracts in 4 databases

(AIDSLINE, MEDLINE, CINAHL, and PsychInfo) were reviewed to locate qualitative studies on women with HIV/AIDS. Using such keywords as women, females,

mothers, HIV, AIDS, qualitative research, naturalistic research, grounded theory, phenomenology, ethnography, and interview, we have already located 25 conference abstracts,

26 published articles, and 1 book chapter, ranging from 4 to 22 pages. Our location of

25 research abstracts reveals that a large number of qualitative studies on women

with HIV/AIDS have been presented at conferences in the past 3 years, affirming the

importance of this area for metasynthesis efforts. A significant number of these conference papers will likely appear in print during the grant period and, therefore,

add to the rich body of literature for metasynthesis work. (Some of the reports of

studies that are not published will likely be retrievable and therefore also contribute

to the data base for this project.) Other results from this search are referred to in the

section on Research Design and Methods. In this paragraph, we emphasized our preparation for the proposed study and further defended the choice of HIV studies as constituting a

good method case. In the following section, we featured only those aspects of each research

team members biography that were directly relevant to the proposed study. We also included

key scholars in the area of metasynthesiswhose work we previously reviewedto participate as members of our Expert Panel.

Expertise of the Research Team

The research team is well prepared to conduct this project. Margarete Sandelowski,

principal investigator, is an internationally recognized expert in qualitative methods. Her research has been in womens health and gender studies, particularly in

the area of reproductive technology. She is Director and Principal Faculty of the

Annual Summer Institute in Qualitative Research held at the University of North

Carolina at Chapel Hill (UNC-CH) School of Nursing, which draws participants

Sandelowski, Barroso / WRITING A QUALITATIVE PROPOSAL

795

from across the United States and several other countries. She is editor of and contributor to the Focus on Qualitative Methods series in Research in Nursing &

Health, a member of the editorial boards of Qualitative Health Research and Field

Methods (a new interdisciplinary journal devoted to qualitative methods), and the

North American editor of Nursing Inquiry, an Australian journal emphasizing critical qualitative methodologies. She is regularly invited to present keynote

addresses and distinguished lectures, conduct workshops, and provide individual

and program consultation on qualitative methods. She has served as visiting

scholar at universities in the United States, Canada, and Australia to disseminate

information about qualitative research and the findings from her qualitative work

on gender and technology. She has published extensively in both nursing and social

science journals and books, with 25 refereed articles on qualitative methods alone.

With Child in Mind (1993), a book-length synthesis of her qualitative studies with

infertile women and couples, was awarded a national book prize from the American Anthropological Association. She is skilled in a variety of qualitative methods

and techniques, including grounded theory, narrative analysis, and social history.

Her latest book, Devices and Desires: Gender, Technology, and American Nursing (to be

published in late 2000, or 2001),3 is a social history of technology in nursing. She is

also skilled in managing very large qualitative data sets, as were collected in the

Transition to Parenthood of Infertile Couples study, in which she served as principal investigator and which was funded by the former National Center for Nursing

Research from 1988-1993 (NRO1707).

Julie Barroso, co-principal investigator, brings both research and clinical experience to this project. She is an adult nurse practitioner with extensive clinical experience in caring for people with HIV disease. She currently maintains a practice with

HIV-positive patients. In addition to completing the qualitative metasynthesis project described above, she has conducted and published qualitative research with

long-term survivors of AIDS and long-term nonprogressors with HIV disease.

She has presented numerous papers on her research to both professional groups

and people with HIV disease. She has received two intramural grants to conduct a

qualitative study exploring fatigue in people with HIV disease. She will also conduct a study of HIV-related fatigue, with funding from OrthoBioTech and from the

UNC-CH School of Nursing, Center for Research on Chronic Illness, which recently

received renewed funding for 5 years from NINR. Moreover, she has maintained an

excellent network of relations in various HIV/AIDS communities, including

researchers and clinicians. She continues to present her work to practitioners and

people living with HIV/AIDS at Area Health Education Consortium (AHEC) HIV

conferences around the state.

The Expert Panel, whose members will provide both consultation and expert

peer review for the proposed project, is made up of scholars with the methodological, substantive, and clinical expertise required for this project. These scholars

include investigators on the metasynthesis projects we discussed previously. Cheryl

Tatano Beck is nationally known for her use of both qualitative and quantitative

research methods, primarily in the area of postpartum depression. She has also conducted quantitative meta-analyses and, therefore, brings to the project an understanding of the comparability of issues relating to quantitative and qualitative

research integrations. Louise Jensen has published one of the few qualitative

796

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / July 2003

metasyntheses of health-related research findings. Having also conducted quantitative meta-analyses, she brings a broad view of issues related to research integration to this project. Margaret Kearney is well known for her qualitative research in the

area of women and substance abuse. She has also completed theoretical syntheses

from her own work and other studies in this area. George Noblit is well known for his

qualitative expertise in the field of education. His text on metaethnography provided the impetus for conducting qualitative metasynthesis research. In addition,

his research in education has been oriented toward the use of qualitative findings to

improve education. Gail Powell-Cope is a substantive and clinical expert in the HIV/

AIDS field. In addition to collaborating with Dr. Barroso in conducting a qualitative

metasynthesis project, she has published several studies on HIV symptom management and AIDS family caregiving. She also has extensive experience working as an

adult nurse practitioner with people with HIV disease. Sally Thorne is internationally known for her expertise in qualitative research, especially in the area of chronic

illness. She recently published the results of a metasynthesis project on diabetes.

Letters of support from these scholars are located in Section I. Section I is not reprinted

here.

Research Design and Methods

The research design is directed toward developing method and therefore entails the

challenging tasks of describing a process-to-create-a-process and experimentation with various approaches to conducting and creating metasyntheses. As is the

case with any qualitative project, the design will be emergent, or highly dependent

on the ongoing results of this experimentation as the study progresses. Although

we separate data collection, analysis, and interpretation here, the better to communicate our research plans, these processes typically proceed together and strongly

influence each other in qualitative studies. Design dictates what the quantitative

researcher will do; in contrast, what the qualitative researcher does determines the

design. We have drawn heavily from what we have learned from our previous

work, discerned from the metasynthesis work of others, and gleaned from the

research integration literature initially to design this project. This literature includes

the work of Cooper (1982, 1989; Cooper & Hedges, 1994) and the Smith and

Stullenbarger (1991) prototype for conducting integrative reviews. These works

describe a reasonable way to begin this project, in that they offer useful guides for

locating, dimensionalizing, and appraising studies. Although we begin this project

with these works in mind, our objective is to build on them and to develop techniques that will fit the qualitative research integration enterprise especially well

and that will preserve the integrity of each study we analyze. We have organized the

description of our research plan to approximate the content and order commonly

associated with research integration studies (Cooper & Hedges, 1994). We describe

issues and/or plans related to (a) defining the limits of a study, (b) bibliographic

retrieval, (c) detailing studies, (d) evaluating studies, (e) conducting the

metasynthesis itself, and (f) ensuring the validity of study procedures.

Introductory paragraphs such as the previous one are crucial to setting the stage and

helping reviewers understand the mind-set of the investigators. This introduction is especially critical here to prepare reviewers for a research plan that looks different from a typical

human subjects study and to reinforce the method-on-method focus of the project. In essence,

Sandelowski, Barroso / WRITING A QUALITATIVE PROPOSAL

797

the proposed project is one big audit trail. Here, we prepared reviewers for a highly specific

research plan but also assured them that we understood the emergent nature of qualitative

research design. We named the concepts and literatures to which we were sensitized but also

suggested that they would have to earn their way into the study to remain guides. The temporal logic of the sections that follow is actual clock time: What we describe first, subsequently,

and last is what we anticipate we will do first, subsequently, and last. The division of the

description of design into clearly defined sections helps writers to maintain their focus solely

on the topic of that section and it offers reviewers a clean and clear narrative flow. Devices

such as section headers and visual displays ease the reading process for reviewers, who often

have a dozen lengthy proposals to critique in any one reviewing period. Although qualitative

research designs, and research integration studies in particular, are iterative and deliberately

nonlinear processes and their phases experientially inseparable, the act of writing requires

that these processes be analytically separated and laid out in some temporal order. However,

we show our recognition of the nonlinear nature of the research process by emphasizing that

our plan is a reasonable way to start the study, even though it might not be the plan we will

actually follow.

Defining the Limits of the Study

In research integration studies, the researchers typically begin by defining the substantive, methodological, and temporal boundaries for study. To begin this study,

we have already identified the broad substantive area as encompassing the experiences of women with HIV/AIDS and the methodological area as qualitative

research. The initial data set for this study will be all qualitative studies published

and/or conducted between 1993 and March 2003 with women in the United States

who are seropositive for HIV in which some aspect of their experience is the primary subject matter. We define qualitative studies as empirical research conducted

in any research paradigm, using largely qualitative techniques for sampling, data

collection, data analysis, and interpretation, with human participants as the sole or

major sources of data. We therefore do not exclude studies conducted in a

neopositivist paradigm in which primarily qualitative techniques are used.

Neopositivism is the prevailing paradigm for quantitative inquiry but only one of

several competing paradigms for qualitative inquiry (Guba & Lincoln, 1994). For

example, grounded theory can be conducted in a neopositivist or constructivist paradigm (Annells, 1996). A neopositivist conducting grounded theory believes in

an external and objectively verifiable reality. In contrast, a constructivist conducting grounded theory believes in multiple, experientially based, and socially constructed realities. For the neopositivist, concepts emerge or are discovered, as if they

were there to be found. The act of discovery is separate from that which is discovered. For the constructivist, concepts are made, fashioned, or invented from data.

What constructivists find is what they made. For the constructivist, all human discovery is creation.

We will include studies completed between 1993, the year in which the first of

these studies appeared (as indicated by our search to date), and March 2003, 2 years

before the anticipated termination of the proposed project. Excluded from our project are (a) qualitative studies in which there are no human subjects per se (as, for

example, in discourse, qualitative content, semiotic, or other qualitative analyses of

media representations of women with HIV/AIDS); (b) qualitative studies about

nonseropositive women and their experiences as mothers, partners, relatives,

798

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / July 2003

friends, and/or caregivers of seropositive persons; and (c) qualitative adjuncts

(such as open-ended questions at the end of a structured questionnaire) to largely

quantitative studies. We anticipate that approximately 30 to 35 studies, with a total

of 450 to 525 pages of text, will make up the bibliographic sample in the method

case. Here, we used numbers to emphasize the volume of data despite an ostensibly small

sample. Sample size is a key focus of strategic disarmament in writing qualitative research

proposals.

Retrieving Literature

We will locate these studies using the techniques for information retrieval that Cooper (1982, 1989) and Cooper and Hedges (1994) described, including (a) informal

approaches, (b) the ancestry approach, (c) the descendency approach, and (d) the

use of online computer databases. Informal approaches include gleaning information about studies by networking with researchers in the target area (here the HIV/

AIDS field) and at conferences and other professional meetings, such as the

National Conference on Women and HIV. The ancestry approach involves tracking

citations from one study to another until citation redundancy occurs. The

descendency approach involves the use of citation indices (such as Social Science

Citation Indexes) to locate studies. The use of computer databases involves the careful selection of keywords and phrases to locate studies in journals, books, dissertations, and conference proceedings included in these databases. A list of the electronic resources available to this project is included in the Resources section of this

proposal. The employment of all of these retrieval channels will make it more likely

we will capture fugitive literature, or studies that are not published or might otherwise escape retrieval. The failure to capture such literature is considered a threat to

the validity of research integrations.

Detailing the Studies

As soon as a study is retrieved, it will be scanned into its own computer file. Each

study will then be detailed, or analyzed for its structure, informational content, and

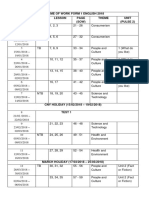

methodological orientation. We will initially use the guide shown in Figure 1 to do

this work. Our use of the word initially is to reinforce the emergent nature of qualitative

design. The results of an application of this guide, using one of the studies in the

Barroso/Powell-Cope (2000) project, are shown in Appendix B (not reproduced here).

Whenever possible, writers should show an example of how a process might be executed.

Concise visual displays are highly effective for communicating process and a sense of order.

This a priori guide will be further refined in the course of the project to ensure the

inclusion of all of the salient features of every study. Each member of the Expert

Panel will independently evaluate the content validity and usability of a refined

version of this tool by applying it to five studies randomly selected from the HIV

studies used to create it. After we receive their evaluations, we will further refine the

guide to include additions or amendments they recommend. The Expert Panel

members will then review a second version of this guide to determine whether the

revisions we made address the problems they noted in reviewing the first version

and to evaluate its broad applicability as a tool to detail any qualitative study. If

these revisions were extensive, each member will be asked to apply this second version of the guide to a different set of five randomly selected studies. They will also

Sandelowski, Barroso / WRITING A QUALITATIVE PROPOSAL

799

Title of study

Investigator(s) name(s)/discipline/institutional affiliation(s)

Publication venue (name and type): e.g., journal, authored/edited book, conference proceeding,

dissertation

Mode of retrieval: e.g., computer database (specify), citation list (specify), personal

communication (specify)

Funding source for study

Research problem/significance

Research purpose(s)/question(s)

Type and area of literature reviewed

A priori theoretical orientations to, assumptions about the target phenomenon

Methodological orientation (name and type; specify with citations provided): e.g., naturalistic

inquiry (Lincoln & Guba, 1985), hermeneutic phenomenology (van Manen, 1990),

constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz, 1990)

Sample: e.g. size, composition, type

Data collection methods or sources (for each one, indicate kind; specify with citations

provided): e.g., interview (narrative, Mishler, 1986), observation (participant, Spradley,

1980), documents (diaries), artifacts (photos)

Data analysis techniques (type; specify citations provided): e.g., qualitative content analysis

(Altheide, 1987), phenomenological thematic analysis (van Manen, 1990), constant

comparison analysis (Strauss & Corbin, 1990)

Techniques to ensure validity/trustworthiness: e.g., audit trail, member validation, peer review,

prolonged contact with participants/time in the field

Interpretive product: e.g., informational summary, theory or other conceptual rendering,

phenomenological description, ethnographic description, visual displays

Major findings

Significance of findings: e.g., for research, for practice

Study format: e.g. conventional (literature review separated from method, results separated from

discussion), other (describe: e.g., results foreshadowed, data merged with interpretation)

Additional information/comments

FIGURE 1:

Topical Guide for Detailing Studies

be asked to comment on whether the revisions solved the problems raised for them

in reviewing the first set of studies. We will further refine the guide if any additional

revisions are warranted after this second review. Consensus on any persistently

troublesome features of the guide will be reached through a process of negotiation

described later in the section on Procedures for Enhancing Study Validity. Although

we will discuss validation techniques later, in a section of the proposal reserved for this purpose, the concern to ensure valid findings is foundational to every design choice. Accordingly, we embed these techniques throughout the design section.

Before the findings from studies can be synthesized, the studies themselves

must be understood for what they uniquely are. Each study must be understood as

providing a specific context for its findings before attempts are made at cross-study

comparisons or combinations of findings. The objectives here are to understand the

particular configuration and confluence of elements characterizing each study as

the investigators themselves presented them and to preserve the integrity of each

study. This objective can be difficult to achieve because of the great diversity in conducting and presenting qualitative research. A hallmark of qualitative research is

variability, not standardization (Popay, Rogers, & Williams, 1998, p. 346). Yet

our goal in this phase of the project is to find a standardized way to characterize

studies that retains their unique character.

The detailing of each study will allow us to address several key problems in

conducting qualitative research integrations. First, unlike quantitative researchers,

qualitative researchers are not necessarily obliged to separate the results of their

studies physically from their discussion of these results. Accordingly, the

reviewer must know how to find the results throughout the research report, and this

skill entails an understanding of various formats and language conventions for the

800

QUALITATIVE HEALTH RESEARCH / July 2003

written presentation of qualitative research. Our goal is to specify these conventions

with the larger goal of ensuring that any two reviewers of any one qualitative study

will identify the same results.

Finding the results of studies is a necessary prelude to determining the topical

similarity of studies, or deciding which studies are really about the same substantive phenomenon, event, or experience. In the qualitative studies of women with

HIV/AIDS we have already located, the findings have addressed diverse topicsall

aspects of the HIV/AIDS experienceincluding responses to the diagnosis, concerns regarding the welfare of children, social relations and stigma, difficulties

obtaining health care, and managing symptoms. Our detailing of each study will

allow us to group studies by the aspects of womens experiences of HIV/AIDS

addressed in the findings of each study. Based on Barrosos metasynthesis (Barroso

& Powell-Cope, 2000), this kind of grouping appears to us now as more relevant

than grouping studies by method. We refer back to preliminary work here to show how it

informed our design choices in the proposed study. Because studies typically contain

findings on more than one aspect of experience, we will use an open system of classification, by which any one study may be placed in more than one group. We will

use Ethnograph 5.0 to place findings on each target experience in separate files for

retrieval and analysis. The specific text management system to be used is less important

than describing how data management, analysis, and interpretation might proceed. Indeed,

writers can simply state that they will use a system (which might simply be a word-processing program) to be determined later. We will then be able to focus on each aspect of

experience and all of the findings related to it. Our goal here is to develop and articulate techniques to isolate the findings around a target experience while maintaining

the connection each finding has both to the individual study generating it and to

other findings around other target experiences in each study. For example, there

will be a set of findings in individual studies and across studies on how women with

HIV manage social relations and on how women manage symptoms that will each

be filed separately. However, the findings in these two topical areas may be combined if we discern a link between managing social relations and managing symptoms. The detailing work in this phase of the project will allow us to see such relations and to communicate how to see them.

This detailing work will permit us also to address another problem in conducting qualitative metasynthesis, namely, determining the methodological comparability of studies and whether and/or how methods influence findings. Given the

varieties of ways in which, for example, grounded theories, phenomenologies, and

ethnographies are conducted and created, and the varieties of practices to which