Motion For Reconsideration

Motion For Reconsideration

Uploaded by

Lawrence CabutajeCopyright:

Available Formats

Motion For Reconsideration

Motion For Reconsideration

Uploaded by

Lawrence CabutajeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Motion For Reconsideration

Motion For Reconsideration

Uploaded by

Lawrence CabutajeCopyright:

Available Formats

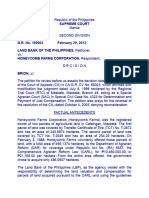

REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES

SUPREME COURT

Manila

FIRST DIVISION

DIDIPIO EARTH-SAVERS’ MULTI-PURPOSE

ASSOCIATION, INCORPORATED (DESAMA),

Et Al.,

Petitioners, G.R. No. 157882

- versus - For Prohibition, Mandamus with

prayer for Temporary

Restraining

ELISEA GOZUN, in her capacity as the Order

Secretary of the Department of

Environment and Natural Resources

(DENR), et al.,

Respondents

.

MOTION FOR RECONSIDERATION

(Of the Decision Dated March 30, 2006)

Petitioners, through counsels, respectfully aver that –

Petitioners received their copy of the Decision promulgated by this Honorable

Court on March 30, 2006 through registered mail on April 7, 2006, which reads –

“WHEREFORE, the instant petition for prohibition and mandamus

is hereby DISMISSED. Section 76 of Republic Act No. 7942 and

Section 107 of DAO 96-40; Republic Act No. 7942 and its

Implementing Rules and Regulations contained in DAO 96-40 –

insofar as they relate to financial and technical assistance

agreements referred to in paragraph 4 of section 2 of Article XII

of the Constitution are NOT UNCONSTITUTIONAL.”

Since the fifteenth (15th) day or the last day within which the petitioners can

move for the reconsideration of said Decision falls on a Saturday, April 22, 2006, this

Motion is being filed on April 24, 2006, the next working day following a nonworking

day.

Availing of their rights under section 1, Rule 52 of the Rules of Court, petitioners

move for the reconsideration of the Decision promulgated on March 30, 2006 based

on the following:

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 1 of 21

GROUNDS

I

An en banc decision is mandatory in cases

where the constitutionality of a law is being

challenged.

II

The power of eminent domain is inherent and

exclusive to the State and may not be

delegated to private entities.

III

The Mining Act and its implementing rules and

regulations allow unjust taking in violation of

Section 9, Article III of the Constitution.

IV

The Mining Act and its implementing rules and

regulations violate the due process

requirements, under Section 1, Article III of the

Constitution, in the valid exercise of the power

of eminent domain.

V

The ‘public use’ character of mining was not factually

established and proved.

DISCUSSION

I

An en banc decision is mandatory in cases where

the constitutionality of a law is being

challenged.

Section 4(2), Article VIII of the 1987 Constitution requires that all cases

involving the constitutionality of a treaty, international or executive agreement, or

law have to be heard and decided by the Supreme Court en banc. In the case at bar,

the Court en banc --

“[R]esolved to return th[e] case to the First Division for

promulgation of its unanimous Decision upholding the

constitutionality of the Mining Law and the related executive

issuances, and dismissing the Petition. There is no need for the

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 2 of 21

Court en banc to tackle the case because the Decision of the First

Division did not declare unconstitutional any law or regulation; it

merely followed the Court en banc’s earlier Decision in La Bugal

B’laan vs. Ramos. In any event, the First Division’s Decision is

AFFIRMED.”

A cursory reading of the Constitutional provision cited above will not reveal

any exemption thereto. The Court sitting en banc should have discussed and

deliberated on the merits of the case and not just affirmed the decision of the First

Division. The procedure observed herein does not substantially comply with Section

4(2), Article VIII of the Constitution because it should be the Court en banc that

ruled on the constitutionality questions. If the Court merely decided to assign the

crafting of the decision to the First Division, it would have complied with its

constitutional mandate.

II

The power of eminent domain is inherent and

exclusive to the State and may not be delegated

to private entities.

Eminent domain is a power inherent to the State that enables it to forcibly

acquire private property for public use and upon payment of just compensation to

the owner.12 As a case cited in a Commentary3 puts it –

“The right of eminent domain is usually understood to be the

ultimate right of the sovereign power to appropriate, not only the

public but the private property of all citizens within the territorial

sovereignty, to public purpose.”

The power of eminent domain is an absolute and plenary power lodged with

the legislature. It is also traditionally executive but the “power is dormant until the

legislature sets it in motion.”3 The rule that a delegated power may not be delegated

further admits of some exceptions. The issue at bar is not an exception.

1

Section 9, Article III, Constitution (1987). See NAPOCOR vs. Spouses Gutierrez et al, G.R. No.

2

, 18 January 1991; Association of Small Landowners in the Philippines, Inc., et al vs. Hon. Secretary

of Agrarian Reform, G.R. No. 78742, 14 July 1989; Manotok et al vs. NHA, G.R. Nos. L55166-67, 21

May 1987.

3

Bernas, Joaquin, S.J. The 1987 Constitution of the Republic of the Philippines: A Commentary

(1996), citing Charles River Bridge vs. Warren Bridge at 347. 3 Ibid.

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 3 of 21

The power of eminent domain may be delegated by Congress to a few, and

hereby exclusive, bodies such as government entities, local government units and

private entities operating public utilities.

The law is clear. Only private entities that operate public utilities work as

exception to the rule barring further delegation of an already delegated power.

The Court in its Decision, citing Presidential Decree No. 512, ruled that –

“The evolution of mining laws gives positive indication that mining

operators who are qualified to own lands were granted the

authority to exercise eminent domain for the entry, acquisition and

use of private lands in areas open for mining operations. This grant

of authority extant in Section 1 of Presidential Decree No. 512 is

not expressly repealed by Section 76 of Rep. Act No. 7942 and

neither are the former statues impliedly repealed by the former.

These two provisions can stand together even if Section 76 of Rep.

Act No. does not spell out the grant of the privilege to exercise

eminent domain which was present in the old law.”4

The Court also upheld the Financial and Technical Assistance Agreement of

Climax-Arimco Mining Corporation, which allows it to negotiate for the acquisition

of lands in violation of the exclusive sovereign right to exercise the power of eminent

domain.

As an absolute power, it may not be restricted except by the

requirements of the ‘public use’ character of the taking and the

determination of payment of just compensation. Any provision in

the subject statute that imposes additional restrictions 5 on the

power of eminent domain is invalid.

Under section 9, Article III of the Constitution, there are three

4

Decision at 21-22.

5

An example of such additional restriction which is invalid is section 94(d) of Republic Act 7942 which

states that –

“Section 94. Investment Guarantees – The contractor shall be entitled to the basic

rights and guarantees provided in the Constitution and such other rights

recognized by the government as enumerated hereunder:

XXX

(d) Freedom from expropriation – The right to be free from expropriation by the

Government of the property represented by investments or loans, or of the property

of the enterprise except for public use or in the interest of national welfare or

defense and upon payment of just compensation. In such cases, foreign investors

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 4 of 21

or enterprises shall have the right to remit sums received as compensation for the

expropriated property in the currency in which the investment was originally made

and at the exchange rate prevailing at the time remittance.”

requirements for a valid exercise of the power of eminent domain. There should be

(1) taking for (2) public use and (3) upon payment of just compensation. The Court,

in the case at bar, has declared Section 76 of Republic Act 7942 as a taking provision.

Two other requirements then remain unsettled.

In the issue of whether or not section 76 of Republic Act 7942 (hence, Mining

Act) and section 107 of Department Order 96-40 (hence, DAO 96-40) constitute

taking, the Court highlighted Presidential Decree No. 512 and declared that –

“Hampered by the difficulties and delays in securing surface rights

for the entry into private lands for purposes of mining operations,

Presidential Decree No. 512 dated 19 July 1974 was passed into law

in order to achieve full and accelerated mineral resources

development. Thus, Presidential Decree No. 512 provides for a new

system of surface rights acquisition by mining prospectors and

claimants. Whereas in Commonwealth Act No. 137 and Presidential

Decree No. 463, eminent domain may only be exercised in order

that the mining claimants can build, construct or install roads,

railroads, mills, warehouses and other facilities; this time, the

power of eminent domain may now be invoked by mining operators

for the entry, acquisition and use of private lands…”4

According to the Court,

“Considering that Section 1 of Presidential Decree No. 512 granted

the qualified mining operators the authority to exercise eminent

domain and since this grant of authority is deemed incorporated in

Section 76 of Rep. Act No. 7942, the inescapable conclusion is that

the latter provision is a taking provision.”5 (Emphasis supplied)

However, in the case at bar, the Court, after declaring that section 76 of the

Mining Act is a taking provision, backtracked and said that –

“Eminent domain is not yet called for at this stage since there are

still various avenues by which surface rights can be acquired other

than expropriation. The FTAA provision under attack merely

facilitates the implementation of the FTAA given to CAMC and

shields it from violating the Anti-Dummy law.”8

4

Decision at 21.

5

Ibid at 22-23.

8

Ibid at 25.

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 5 of 21

The concept of “taking” assumes that the surface owners and/or possessors

refuse to sell hence necessitating the exercise of the Government of its sovereign

power of eminent domain. By saying that section 76 of Republic Act No. 7942 is a

taking provision, the Court has ruled on the impossibility or the inability to still enter

into voluntary agreements or sale between the surface owners and the mining

contractor.

The Court already clarified this point in Association of Small Landowners vs.

Secretary of Agrarian Reform6. Thus,

“Eminent domain is an inherent power of the State that enables it

to forcibly acquire private lands intended for public use upon

payment of just compensation to the owner. Obviously, there is no

need to expropriate where the owner is willing to sell under terms

also acceptable to the purchaser, in which case, an ordinary deed

of sale may be agreed upon by the parties. It is only where the

owner is unwilling to sell, or cannot accept the price or other

conditions offered by the vendee, that the power of eminent

domain will come into play to assert the paramount authority of

the State over the interests of the property owner.” (Emphasis

supplied)

The Court in its Decision misapplied the doctrine it enunciated in the La Bugal7

case. In that case, there was no finding of taking and therefore the said ruling is of

no moment and is therefore irrelevant.

III

The Mining Act and its implementing rules and

regulations allow unjust taking in violation of

Section 9, Article III of the Constitution.

Eminent domain is the power of the State while expropriation is merely the

procedure by which the State is to exercise this power. The Court confuses the two

by saying that there is yet no need to exercise the power of eminent domain simply

because there are other avenues through which surface rights may be obtained.

6

Association of Small Landowners of the Philippines vs. Secretary of Agrarian Reform, G.R. No.

78742, 14 July 1989.

7

La Bugal B’laan Tribal Association, Inc. vs. Ramos, G.R. No. 127882, 1 December 2004.

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 6 of 21

The power of eminent domain is already at play when the State takes property. 8

In this case, the Court admits that the State takes property by virtue of Section 76

of the Mining Act. Therefore, upon the effectivity of the Mining Act and the

execution of the Financial and Technical Assistance Agreements, the State is

already exercising its power of eminent domain.

Accordingly, the pre-conditions to the exercise of this power must have

already been complied with, even by mere provision of the determination that the

taking is for public use and by providing a basis for the determination of just

compensation. As will be explained later, neither of these two pre-conditions has

been met.

Section 9, Article III of the Constitution is unequivocal. Taking of private

property must be for public use and upon just compensation.

“Obviously, however, the power is not without limits: first, the taking

must be for public use, and second, that just compensation must be

given to the private owner of the property. These twin proscriptions

have their origin in the recognition of the necessity of achieving

balance between the State interests on the one hand and private rights

upon the other hand, by effectively restraining the former and

affording protection to the latter.”9

This arbitrary and encompassing exercise of the power of eminent domain

under Section 76 of the Mining Act is precisely the abuse from which the Constitution

protects private rights. Further, it must be pointed out that the Mining Act

subscribes to these proscriptions but only as regards the expropriation of property

“represented by investments or loans, or of the property of the [mining]

enterprise”. 10 In so doing, the Mining Act extends the constitutional protection

exclusively to mining concessionaires thereby violating the constitutional demands

of equal protection of the law.

Any taking that does not comply with these constitutional restrictions is

unlawful. And, any law allowing for this unlawful exercise must be struck down for

its patent unconstitutionality.

8

Republic vs. Vda. De Castellvi, G.R. No. 146587, 2 July 2002.

9

Ibid.

10

Supra note 5.

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 7 of 21

IV

Section 76 of Republic Act 7942 and section 107

of Department Order 96-40 violate the due

process requirements, under Section 1, Article

III of the Constitution, in the valid exercise of

the power of eminent domain.

Section 1, Article III of the 1987 Constitution mandates that “no person shall

be deprived of life, liberty or property without due process of the law, nor shall any

person be denied the equal protection of laws”. This paramount right serves as check

on the acts of the State to ensure that the rights of individuals are protected and

respected. Thus, in the case of Manotok--

“The due process clause cannot be rendered nugatory every time a

specific decree or law orders the expropriation of somebody’s

property and provides its own particular manner of taking the

same. Neither should the courts adopt a hands-off policy just

because the public use has been ordained as existing by the decree

or the just compensation has been fixed and determined

beforehand by a statute.”11

Therefore, the validity of the exercise of eminent domain even if it emanated

directly from Congress through a statute should still be subjected to judicial

scrutiny. The Court had occasion to clarify this in a recent case and said that the

exercise of the power of eminent domain may appear to be ‘harsh and

encompassing’ but judicial review limits the exercise thereof by looking at (1)

adequacy of the compensation, (2) the necessity of the taking, and (3) the publicuse

character of the purpose of the taking.12

The Mining Act and its implementing rules

and regulations do not provide for the

determination and payment of just

compensation which violates section 9,

Article III of the

Constitution.

Just compensation is defined as the full and fair equivalent of the property

taken from its owner by the expropriator.13 It has been described as the just and

complete equivalent of the loss which the owner of the thing expropriated has to

11

Supra note 6.

12

Robern Development Corporation vs. Quitain et al, G.R. No. 135042, 23 September 1999.

13

Supra note 5.

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 8 of 21

suffer by reason of the expropriation.14 What makes the compensation just is when

the owner of the property expropriated receives a sum equivalent to what is fair

market value.15

The Court in its Decision ruled that –

“While the Court declares that the assailed provision is a taking

provision, this does not mean that it is unconstitutional on the

ground that it allows taking of property without the determination

of public use and the payment of just compensation.16

XXX

There is also no basis for the claim that the Mining Law and its

implementing rules and regulations do not provide for just

compensation in expropriating private properties. Section 76 of

Rep. Act No. 7942 and Section 107 of DAO 96-40 provide for the

payment of just compensation.17” (Emphasis supplied)

Contrary to the Court’s pronouncement, the Mining Act and its implementing

rules and regulations, particularly the subject provisions, do not provide for the

determination of payment of just compensation. A re-examination of the cited

provisions becomes essential. The pertinent provisions are cited anew.

Thus --

Section 76. Entry into Private Lands and Concession Areas –

“Subject to prior notification, holders of mining rights shall not be

prevented from entry into private lands and concession areas by

surface owners, occupants or concession areas when conducting

mining operations therein: Provided, That any damage done to the

property of the surface owner, occupant or concessionaire as a

consequence of such operations shall be properly compensated as

may be provided in the implementing rules and regulations …”

(Emphasis supplied in bold)

The pertinent provisions in the implementing rules and regulations, Department

14

Supra note 2, at 352.

15

Ibid.

16

Decision at 23

17

Decision at 26.

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 9 of 21

Order 96-40, are –

Section 105. Entry into Lands

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 10 of 21

“The holder(s) of mining right(s) shall not be prevented from entry

into its/their contract/mining area(s) for the purpose(s) of

exploration, development and/or utilization…”

Section 107. Compensation to the Surface Owner and Occupant

“Any damage done to the property of the surface owner, occupant

or concessionaire thereof as a consequence of the mining

operations or as a result of the construction or installation of the

infrastructure mentioned in section 104 above shall be properly and

justly compensated…”

The Court in deciding this case relied on Sections 105, 106 and 107 of

Department Order 96-40 to allegedly show that the questioned legislation actually

provide for the payment of just compensation. The above-cited provisions, and on

which the Court based its interpretation, refer to PAYMENT OF COMPENSATION FOR

DAMAGES INCURRED in either actual mining operation or installation of

machineries, et al. This is not the just compensation being referred to in relation to

the exercise of the power of eminent domain.

What is required under the Constitution is JUST COMPENSATION FOR THE

TAKING itself and not just for the subsequent payment of damage after entry. In

the case of Familara vs. J.M. Tuason & Co.,18 it was held that the application of a

provision of law which “places restraint upon the exercise and enjoyment by the

owner of certain rights over its property, is justifiable only if the government takes

possession of the land and is in a position to make a coetaneous payment of just

compensation to its owner.” Thus --

“To hold a mere declaration of an intention to expropriate, without

instituting the corresponding proceeding therefore before the

courts, with assurance of just compensation, would already

preclude the exercise by the owner of his rights of ownership over

the land, or bar the enforcement of any final ejectment order that

the owner may have obtained over an intruder of the land, is to

sanction an act which is indeed confiscatory and therefore

offensive to the Constitution. For it must be realized that in a

condemnation case, it is from the condemnor’s taking possession of

the property that the owner is deprived of the benefits of

ownership, such as possession, management and disposition

thereof.”

18

Familara vs. J.M. Tuason & Co 49 SCRA 338 (1973).

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 11 of 21

It cannot be over-emphasized that taking without determining the payment

of just compensation is unconstitutional. The Constitution demands that for the

exercise of eminent domain to be valid, the three elements should be present –

there is a taking but only for public use and upon payment of just compensation.

This Court has already ruled that the questioned provision, section 76 of the Mining

Act, is a taking provision. Under the Mining Act and its implementing rules and

regulations, there was absolutely no mention of or provision for the payment of just

compensation arising from the taking. The Court cannot do anything else but to

declare the questioned provisions as unconstitutional.

The Court read sections 105, 106 and 107 of Department Order 96-40 to mean

that not only do they provide for the determination of payment of just compensation

but also provide for the jurisdiction of the administrative agencies to determine the

adequateness and amount of just compensation. The Court in deciding in such a

manner is dangerously treading into law-making in reading what is not written in the

law.

The Court interpreted the sections to refer to the venue in which the surface

owner, occupant or concessionaire can challenge the adequateness of the just

compensation. The main problem is that payment of just compensation is not

provided for in the Mining Act and its implementing rules and regulations which are,

believe it or not, in violation of section 9, Article III of the Constitution. How can

the surface owners, occupants or concessionaires even bring up the matter of just

compensation when the provision is only for compensation for damages?

The Mining Act and its implementing rules and regulations allow taking

without payment of just compensation, which is patently illegal under the 1987

Constitution.

Determination of payment of just

compensation should be judicial in both

form and function.

The process for determination of just compensation follows an

unconstitutional process mandated under Presidential Decree No. 512 and Mining

Act and its Implementing Rules and Regulations. The Court in its Decision said that-

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 12 of 21

“There is nothing in the provisions of the assailed law and its

implementing rules and regulations that exclude the courts from

their jurisdiction to determine just compensation in expropriation

proceedings involving mining operations. Although Section 105

confers upon the Panel of Arbitrators the authority to decide cases

where surface owners, occupants [and] concessionaires refuse

permit holders entry, thus, necessitating involuntary taking, this

does not mean that the determination of the just compensation by

the Panel of Arbitrators or the Mines Adjudication Board is final and

conclusive. The determination is only preliminary unless accepted

by all parties concerned… The original and exclusive jurisdiction of

the courts to decide determination of just compensation remains

intact despite the preliminary determination made by the

administrative agency.”

Accordingly, there is nothing in these provisions that provide for judicial

determination of just compensation.

The Court cannot base its Decision on the cited provisions as contained in DAO

96-40 because, as it was explained earlier, they refer to compensation for damages

incurred and not to payment of just compensation as a result of expropriation or

taking. If we take these provisions out of the equation, nothing will remain for the

Court to base its Decision on. These sections are but blanket provisions relating to

all conflicts arising from surface ownership or possession.

There is no specific provision solely for just compensation.

Assuming arguendo that the phrase “in the case of disagreement or in the

absence of an agreement” can be stretched to include payment of just

compensation, it is still violative of the due process requirement under the

Constitution.

The question on the judicial determination of just compensation has been

settled in the case of Export Processing Zone Authority vs. Dulay, in that the

Supreme Court held:

“The determination of ‘just compensation’ in eminent domain

cases is a judicial function. The executive department or

legislature may make the initial determinations but when a party

claims a violation of the guarantee in the Bill of Rights that private

property may not be taken for public use without just

compensation, no statute, decree, or executive order can mandate

that its own determination shall prevail over the court’s findings.

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 13 of 21

Much less can the courts be precluded from looking into the ‘just-

ness’ of the decreed compensation”19 (Emphasis ours)

In that case, the Honorable Court declared unconstitutional a law that

eliminated the court’s discretion to determine just compensation. Similarly,

Republic Act No. 7942 and its implementing Rules also oust the Court of its

jurisdiction to determine the payment of just compensation by transferring that

power to the Panel of Arbitrators.

The Court wants to persuade us that the determination at the level of the

Panel of Arbitrators is only an initial determination which does not work to oust the

courts of their jurisdiction.20 Accordingly, the decision of the Panel of Arbitrators

may be appealed to the Mines Adjudicatory Board.21 Then, the decision of the Mines

Adjudicatory Board may still be appealed by petition for review on certiorari to the

Supreme Court22. The problem with this procedure is that by the time the issue

comes to the court, only questions of law may be raised. 23 That leaves the parties

with no available venue where they can question the adequateness of the

compensation and the necessity of the taking.

The ruling in the case Philippine Veterans Bank vs. Court of Appeals24 is not

applicable in the case at bar since the Department of Agrarian Reform was expressly

vested with the jurisdiction to adjudicate agrarian reform matters which include the

determination of questions of just compensation. There was no such provision under

the Mining Act and its implementing rules and regulations. The jurisdiction of the

Panel of Arbitrators and the Mines Adjudicatory Board insofar as compensation is

concerned is limited only to the determination of compensation for damages arising

out of the mining operation or the installation of mining implements and not as

regards just compensation in the exercise of eminent domain powers.

Further, the mining disputes arising from the exercise of power of eminent

domain are actually disputes between the Government, as the one exercising the

power of eminent domain, and the surface owners, occupants and concessionaires.

19

Export Processing Zone Authority vs. Dulay (316 SCRA 305).

20

Section 77(c), RA 7942. Section 107, DENR Admin. Order No. 96-40.

21

Section 78, Rep. Act No. 7942 (1995).

22

Last paragraph, section 79, Rep. Act No. 7942 (1995).

23

Section 1, Rule 45, Rules of Court.

24

Philippine Veterans Bank vs. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 132767, 18 January 2000.

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 14 of 21

Therefore, the jurisdiction to decide such issues is lodged originally and exclusively

with the courts.

Finally, the Court in its Decision attempts to limit the courts’ determination

of just compensation by coining the term “involuntary taking”. There is no such

concept. “Taking”, in both legal and colloquial parlance, is by its very nature

forcible and in any given case -- involuntary. Taking has to be involuntary; otherwise,

the transfer of property and ownership is in the form of sale.

Reliance on Presidential Decree 512 to

determine the amount of just

compensation is fatal.

Section 107 of DAO 96-40 states that “compensation shall be based on the

agreement entered into between the holder of mining rights and the surface owner,

occupant or concessionaire thereof or where appropriate in accordance with P.D.

No. 512.” The latter, in turn, states that -

“Provided, further, That to guarantee such compensation to the

surface owners, the prospector or claimowner shall post a bond

with the Bureau of Mines in an amount to be fixed by the Director

of Mines based on the type of property and the prevailing price of

lands in the area where prospecting and other mining activities are

to be conducted and with surety or sureties satisfactory to the

Director of Mines. The decision of the Director of Mines may be

appealed within five (5) days from receipt thereof to the Secretary

of Natural Resources, whose decision shall be final.”

Again, it is obvious from these two provisions that the compensation being

referred to is for damages in the course of undertaking the mining activity. That is

not what the compensation referred to by the constitutional requirements in the

exercise of eminent domain.

However, assuming arguendo that section 76 of the Mining Act can still be

stretched to include payment of compensation in the exercise of eminent domain,

the emphasis given by the Court in its Decision on PD 512 is likewise misplaced since

it restricts the judicial determination of the amount of just compensation to an

amount indicated in the law that does not use as base, fair market value of the

property at the time of taking, which is the prevailing rule. 25 Instead, it followed

25

See e.g, Republic vs. Vda. De Castellvi, 58 SCRA 339, 15 August 1974.

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 15 of 21

the rule in a long line of Presidential Decrees on summary and automatic

expropriation issued by President Marcos in his exercise of legislative powers, which

Decrees have already been declared unconstitutional by the Supreme

Court.26

The ‘public use’ character of mining was not

factually established and proved.

The Court in its Decision ruled that –

“Mining industry plays a pivotal role in the economic development

of the country and is a vital tool in the government’s thrust of

accelerated recovery (citing Executive Order No. 211). The

importance of the mining industry for national development is

expressed in Presidential Decree No. 463:

WHEREAS, mineral production is a major support of the

national economy, and therefore the intensified discovery,

exploration, development and wise utilization of the country’s

mineral resources are urgently needed for national development.

Irrefragably, mining is an industry which is of public benefit.

That public use is negated by the fact that the state would be

taking private properties for the benefit of private mining firms or

mining contractors is not at all true.” (Emphasis supplied)

The public-use character of mining is

neither expressly provided nor factually

proved.

Public use is defined broadly, in that as long as the purpose of the taking is

public then the power of eminent domain comes into play. 27

The Court looked at Executive Order 211 and Presidential Decree 463 to glean

what is the public-use character of mining. This is not proper considering that the

reference as to what is the public-use character of mining should be made on what

the Mining Act and its implementing rules and regulations express it to be.

26

Manotok, supra.

27

Heirs of Juancho Ardona v. Reyes, G.R. Nos. L-60549, L-60553 to 60555, 26 October 1983.

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 16 of 21

Public use equals public benefit?

The Court asserts that, “mining is an industry which is of public benefit”. It

is not made clear as to how it can benefit the public and as to how it can serve a

public use.

Mining is not a necessary undertaking and its character is not for public use.

It is the individual, the domestic and/or foreign corporation that undertake mining

in this country, for profit. It has no apparent or express public use. It does not refer

to any activity necessary or incidental to the State’s functions.

Just a cursory review of the provisions of the Mining Law and the questioned

FTAA will show that the State’s obligation is really to ensure that mining contractors

do not come out of the mining venture poorer than when they came in as guaranteed

by the incentives from the Board of Investments to acquire corporate tax and other

tax and duty holidays and the assurance of prompt repatriation of the pre-operating

expenses and property expenses of the mining contractor.

The lack of full control by the State in the operation and management of a

mining enterprise may make whatever sharing arrangements entered into as

ineffective as shown in fact by the section on fiscal regime in the Mining Act and the

CAMC FTAA, more so, in the measly amount that constitutes the government’s share.

This falls under the concept of diseconomy wherein the State is put into an

economic disadvantage as a consequence of its lack of control over its nonrenewable

resources like mineral resources. Its real presence, therefore, negates the ‘public

benefit’ reasoning that the Court adapted in this case.

No viable empirically proven causation between restricted investments in

extractive natural resource industries, such as mining, and slower growth was

presented, besides simply asserting it to be a truism that restricting investments in

extractive natural resources slows growth.

The natural resources curse, on the other hand, is a phenomenon that is

demonstrable empirical fact. With few exceptions, countries that rely the most on

their natural resources sector are the ones that exhibit the slowest growth.

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 17 of 21

Empirical and analytic studies 28 prove that contrary to the common belief that

economic prosperity is a given for resource-rich countries, the truth is that they

tended to be high-priced economies and, consequently, tended to miss out on

export-led growth. Natural resource abundance can crowd out drivers of growth,

such as traded-manufacturing activities, education and even growth-promoting

entrepreneurial activities. Reliance on the public benefit, or economic growth,

through mining has no empirical leg to stand on and therefore should not be the

basis of any form of judicial assumption or notice.

Given that the public-use character of mining is not expressly provided and

that public benefit is not factually and sufficiently established, in the absence,

therefore, of the declaration of public use in the challenged statute, the criteria of

real contributions to economic growth and the general welfare of the country should

now be used as basis for examination.

Section 2 of Article XII of the Constitution mandates that any agreement

entered into by the State should be based on real contributions to economic growth

and the general welfare of the country.

However, given the terms and conditions the government entered into with

CAMC through the FTAA, before any real contributions to economic growth can be

realized, however, it is stated that CAMC has to first fully recover its pre-operating

expenses and property expenses incurred during the pre-operating expenses. Only

after this has happened can the government have the right to share in the net

revenue32, which, based on the interpretation given by the Court in La Bugal, only

refer to taxes, fees and duties; these constitute what is known as the ‘government

share’.

The government, on behalf of the State, must stand to receive a larger share

as the owner in trust of the mineral resources. It has a larger stake in the

exploration, development and utilization of minerals. Because the Constitution

requires that the terms and conditions must be provided in a general law on real

28

See SACHS, J.D and WARNER, A.M., The Curse of Natural Resources, European Economic

Review 45, 827 (2001). 32 11.2, CAMC FTAA.

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 18 of 21

economic growth and general welfare, the law therefore must be clear as to its

bases for computation.

Under the second paragraph of Section 81 of the Mining Act, the government

stands to receive taxes, duties, fees and the like from the foreign contractor, and

no other. The law does not provide for a basis of determining the equitable share of

the government in the light of the risks attendant to mining activities. This is very

clear from the provision itself.

Further, the taxes, duties, fees and the like that the government stands to

earn from the mining proceeds or profits are not the earnings contemplated by law

to be earned by the government. These are not returns on investment. These are

imposed on the basis of the taxing power of the State. They are enforced

proportional contributions from persons and property, levied by the State by virtue

of its sovereignty, for the support of government and for all public needs. They are

not the gains or benefits contemplated by law for government to receive in the

course of the mining ventures. The State therefore cannot waive its real and

realizable income from the mining operations as owner in trust of the mineral

resources in exchange of taxes, duties, fees and the like.

While Congress should be given some leeway for determining how it computes

for a justifiable and equitable share, it must, in the general law already provide for

the basis for its computation. Worse, it cannot delegate the power to determine the

guides for computation to the executive. Otherwise, this would result in undue

delegation of legislative prerogatives.

Lastly, Republic Act No. 8974 (2000) now governs the expropriation of private

properties for national government projects; the latter is defined to include national

government infrastructure, engineering works and service contracts. It means that

if this law is applied vis-à-vis the taking, as is the situation in the case at bar, the

State must, upon filing of the complaint and after due notice to the defendant,

immediately pay the owner of the property in the amount equivalent to the sum of

(1) 100% of the value of the property based on the current relevant zonal valuation

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 19 of 21

of the Bureau of Internal Revenue and (2) the value of the improvements and/or

structures on the land to be expropriated.29

The current fiscal crisis is already of judicial notice that’s why according to

the ruling in La Bugal, a restrictive interpretation of the financial and technical

assistance agreement will not lie. According to the Constitution, the basis should be

“real contributions’ but there can be no real contribution to economic growth

because (1) the compensation of the lands under the FTAA must be immediately

paid, per Republic Act 8794, which now applies to national government

infrastructure projects, including service contracts and (2) full recovery must first

be had by the mining company before the government gets its share under section

81 of Republic Act 7942.

The Court ruling in Manotok should give us pause, in that –

“The principle of non-appropriation of private property for private

purposes however remains. The legislature, according to the Guido

case, may not take the property of one citizen and transfer it to

another, even for a full compensation, when the public interest is

not thereby promoted. The Government still has to prove that

expropriation of commercial properties in order to lease them out

also for commercial purposes would be “public use” under the

Constitution.”30

If the public use character of the expropriation is not established, and when

the Executive, through its agencies, exercises the power of eminent domain in

behalf of mining contractors and other private entities, it operationally takes away

the property of A and gives it to B.

Upon examination, it is apparent that the Mining Act and its implementing

rules and regulations were not able to pass the test and meet the requirements of

constitutionality imposed and mandated by Section 9, Article III of the 1987

Constitution.

29

Sections 4(a) and 7, Rep. Act No. 8974 (2000).

30

Supra note 6.

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 20 of 21

PRAYER

WHEREFORE, in view of the foregoing, it is most respectfully prayed that:

(a) This Motion for Reconsideration be set for oral argumentation for the

purpose of clarifying new issues raised in the Decision promulgated on March

30, 2006;

(b) After notice and hearing --

1. The Decision promulgated on March 30, 2006 be set aside and vacated;

2. Republic Act 7942 and its implementing rules and regulations be declared

unconstitutional;

3. The CAMC FTAA be declared unconstitutional, illegal and void;

Such other reliefs that are just and equitable under the premises are likewise

prayed for.

Quezon City for Manila, 24 April 2006.

Respectfully submitted.

Marvic MVF Leonen

Edgar dL. Bernal

Ingrid Rosalie L. Gorre

Melizel F. Asuncion

Francis J.G. Ballesteros

Counsels for Petitioners

Legal Rights and Natural Resources Center-

Kasama sa Kalikasan/ Friends of the Earth-

Philippines (LRCKsK/FoE-Phil), Inc.

#87-B Madasalin St., Teachers’ Village,

Diliman, Quezon City

Motion for Reconsideration, DESAMA, Page 21 of 21

You might also like

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument7 pagesMotion For ReconsiderationJurilBrokaPatiño85% (13)

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument11 pagesMotion For ReconsiderationAtty. Emmanuel Sandicho93% (14)

- Sample Motion Fore ReconsiderationDocument5 pagesSample Motion Fore ReconsiderationJia Frias90% (10)

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument17 pagesMotion For ReconsiderationEulo Lagudas82% (17)

- Motion For Reconsideration Estafa ComplaintDocument3 pagesMotion For Reconsideration Estafa ComplaintCarlo Castillo92% (12)

- Motion For Reconsideration RTC OrderDocument4 pagesMotion For Reconsideration RTC OrderKristen Noche100% (3)

- Motion For Reconsideration (OCP)Document4 pagesMotion For Reconsideration (OCP)adelainezernagmail.com100% (6)

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument6 pagesMotion For ReconsiderationATTORNEY100% (6)

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument10 pagesMotion For ReconsiderationAlfie de Guzman73% (11)

- Motion For Reconsideration FormatDocument3 pagesMotion For Reconsideration FormatKendrick SiaoNo ratings yet

- Motion For Reconsideration - Re Qualified-TheftDocument6 pagesMotion For Reconsideration - Re Qualified-TheftAhmad Abduljalil50% (2)

- Motion For Reconsideration Sample, Rape CaseDocument6 pagesMotion For Reconsideration Sample, Rape CaseAly Concepcion100% (3)

- Motion For Extension of TimeDocument3 pagesMotion For Extension of TimeAttyKaren Baldonado-GuillermoNo ratings yet

- Petition For Review DOJDocument15 pagesPetition For Review DOJJoseph John Madrid Aguas83% (12)

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument1 pageMotion For ReconsiderationAgnes GamboaNo ratings yet

- Motion For Extension To File AnswerDocument2 pagesMotion For Extension To File AnswerMae Ann Sarte Acha50% (2)

- AnswerDocument20 pagesAnswerLeona Dacillo100% (2)

- Entry of AppearanceDocument2 pagesEntry of AppearanceYohan AgustinNo ratings yet

- Regional Trial Court: Paderenga v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 115407, August 28, 1995Document3 pagesRegional Trial Court: Paderenga v. Court of Appeals, G.R. No. 115407, August 28, 1995RoMeo100% (6)

- Sample Motion For Reconsideration - POEADocument8 pagesSample Motion For Reconsideration - POEAMichael MalvarNo ratings yet

- Petition For Review Rule 45Document8 pagesPetition For Review Rule 45Vincent Quiña Piga100% (7)

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument8 pagesMotion For ReconsiderationDiaz100% (1)

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument6 pagesMotion For ReconsiderationJayran Bay-an100% (4)

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument3 pagesMotion For ReconsiderationKinitDelfinCelestial50% (2)

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument7 pagesMotion For ReconsiderationDrekyrie Rosenving50% (4)

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument4 pagesMotion For ReconsiderationRossette AnaNo ratings yet

- Motion For Reconsideration - GonzalesDocument7 pagesMotion For Reconsideration - Gonzaleslyndon melvi sumiog100% (1)

- Notice of AppealDocument2 pagesNotice of Appealcha tomaro100% (1)

- Comment On Motion To DismissDocument4 pagesComment On Motion To DismissEliasa Arcano100% (2)

- Motion To Admit With Entry of Appearance (Reed)Document4 pagesMotion To Admit With Entry of Appearance (Reed)Gerard Nelson Manalo100% (2)

- Comment Opposition To The Petition Certiorari Asialink V Madriaga SCDocument20 pagesComment Opposition To The Petition Certiorari Asialink V Madriaga SCDence Cris Rondon100% (4)

- Sample Appellant BriefDocument6 pagesSample Appellant BriefKaye Pascual89% (9)

- Motion For ReinvestigationDocument16 pagesMotion For ReinvestigationStephanie Viola50% (2)

- Taxation 2 Case DigestsDocument148 pagesTaxation 2 Case DigestsMa BelleNo ratings yet

- Motion For Reconsideration de LimaDocument24 pagesMotion For Reconsideration de LimaMelvin Pernez100% (1)

- Motion For Reconsideration DamagesDocument8 pagesMotion For Reconsideration DamagesEuniceNo ratings yet

- Motion For Reconsideration (Lomibao)Document6 pagesMotion For Reconsideration (Lomibao)Patricia CastroNo ratings yet

- Motion For Reconsideration.Document7 pagesMotion For Reconsideration.Jackie Calayag100% (1)

- Motion For Extension of Time SampleDocument4 pagesMotion For Extension of Time SampleMichael Parreño Villagracia75% (4)

- Answer: Julia Estanislao Aquino CA-G.R. SP No. 148635Document6 pagesAnswer: Julia Estanislao Aquino CA-G.R. SP No. 148635Atlas LawOffice67% (3)

- Sample Petition For ReviewDocument34 pagesSample Petition For ReviewPaula CarlosNo ratings yet

- Petition For Review To CADocument17 pagesPetition For Review To CAKuya Torney100% (3)

- Republic of The Philippines Court of Appeals National Capital Judicial Region ManilaDocument7 pagesRepublic of The Philippines Court of Appeals National Capital Judicial Region ManilaArisse Jannah BarreraNo ratings yet

- Motion To Withdraw HoshiyaDocument3 pagesMotion To Withdraw Hoshiyaedcelquiben100% (2)

- Sy-Motion To Inhibit 2Document7 pagesSy-Motion To Inhibit 2ROMY100% (1)

- Verified AnswerDocument5 pagesVerified AnswerChucky VergaraNo ratings yet

- Motion To Reduce BondDocument6 pagesMotion To Reduce Bondemz318100% (1)

- Motion For ReconsiderationDocument6 pagesMotion For Reconsiderationkyle turinganNo ratings yet

- Motion To Admit EDDIEDocument2 pagesMotion To Admit EDDIEMarianoFlores100% (1)

- Appellee,: (To The Respondents' Notice of Appeal With Memorandum of Appeal)Document3 pagesAppellee,: (To The Respondents' Notice of Appeal With Memorandum of Appeal)Jhoey Castillo BuenoNo ratings yet

- Motion For Reconsideration 2Document7 pagesMotion For Reconsideration 2Marie Dwynwen100% (1)

- Motion To Amend The OrderDocument3 pagesMotion To Amend The OrderJohn Paul FabellaNo ratings yet

- Motion For Reconsideration - Kristianjan Garcia (Plea Bargain)Document11 pagesMotion For Reconsideration - Kristianjan Garcia (Plea Bargain)gilberthufana446877100% (3)

- Motion To Render Judgment RAMDocument2 pagesMotion To Render Judgment RAMJocelyn VirayNo ratings yet

- Reply To Answer DunaloDocument8 pagesReply To Answer Dunaloattyvan100% (2)

- Petition For ReviewDocument9 pagesPetition For ReviewRaffy PangilinanNo ratings yet

- Petition For Certiorari & Prohibition - Salvador Estipona Vs Judge Frank Lobrigo v1 - 1Document70 pagesPetition For Certiorari & Prohibition - Salvador Estipona Vs Judge Frank Lobrigo v1 - 1Watz Rebanal100% (2)

- Appellees Brief Asialink V MadriagaDocument53 pagesAppellees Brief Asialink V MadriagaDence Cris RondonNo ratings yet

- Eminent Domain KPDocument83 pagesEminent Domain KPZce AtonNo ratings yet

- What Are The Requisites For A Judicial Review?Document5 pagesWhat Are The Requisites For A Judicial Review?bantucin davooNo ratings yet

- Chavez V PEA and AMARI G.R. No. 133250. July 9, 2002. Facts IssueDocument4 pagesChavez V PEA and AMARI G.R. No. 133250. July 9, 2002. Facts IssueFbarrsNo ratings yet

- 10 Land Acquisitin ConflictsDocument20 pages10 Land Acquisitin Conflictsayxx zNo ratings yet

- Tax Reviewer Vitug AcostaDocument5 pagesTax Reviewer Vitug AcostaShiela Mae VillaruzNo ratings yet

- LAW 1100 - Constitutional Law I - JD A5. G.R. No. 222159 - Rebadulla vs. ROP - Full TextDocument11 pagesLAW 1100 - Constitutional Law I - JD A5. G.R. No. 222159 - Rebadulla vs. ROP - Full TextJOHN KENNETH CONTRERASNo ratings yet

- G.R. No. 169903 February 29, 2012Document17 pagesG.R. No. 169903 February 29, 2012ericson dela cruzNo ratings yet

- City Government of QC vs. ErictaDocument7 pagesCity Government of QC vs. ErictaArlando G. ArlandoNo ratings yet

- "Property" and Investment-Backed Expectations in Ridesharing Regulatory Takings Claims, 39 U. Haw. L. Rev. 301 (2017)Document13 pages"Property" and Investment-Backed Expectations in Ridesharing Regulatory Takings Claims, 39 U. Haw. L. Rev. 301 (2017)RHTNo ratings yet

- Bears CONSTI II Atty. Ingles Dean CandelariaDocument80 pagesBears CONSTI II Atty. Ingles Dean CandelariaSofia DavidNo ratings yet

- Week 3 FinaleDocument5 pagesWeek 3 FinaleJean Francois OcasoNo ratings yet

- Mod17Wk15-Constitutional-LawDocument30 pagesMod17Wk15-Constitutional-LawTiara LlorenteNo ratings yet

- "The Welfare of The People Shall Be The Supreme Law" and Use (What Is) Yours So As Not To Harm (What Is) of Others"Document6 pages"The Welfare of The People Shall Be The Supreme Law" and Use (What Is) Yours So As Not To Harm (What Is) of Others"Kitem Kadatuan Jr.0% (1)

- Digest Land Bank of The PH v. EscarillaDocument2 pagesDigest Land Bank of The PH v. EscarillaTrina RiveraNo ratings yet

- 121 135Document23 pages121 135Dean Graduate-SchoolNo ratings yet

- Notes On Eminent Domain and Just2Document36 pagesNotes On Eminent Domain and Just2AB AgostoNo ratings yet

- Ust Golden Notes Law On Public CorporationspdfDocument57 pagesUst Golden Notes Law On Public CorporationspdfImmediateFalcoNo ratings yet

- City of Baguio vs. Nawasa (106 Phil. 144 (1959) )Document8 pagesCity of Baguio vs. Nawasa (106 Phil. 144 (1959) )csalipio24No ratings yet

- Ra 7227 PDFDocument24 pagesRa 7227 PDFArchie RamosNo ratings yet

- Estate of Jimenez v. PEZA, G.R. No. 137285, January 16, 2001Document3 pagesEstate of Jimenez v. PEZA, G.R. No. 137285, January 16, 2001Leyard100% (1)

- Case Digest (ASSOCIATION OF SMALL LANDOWNERS IN THE PHILIPPINES, INC., ET AL. vs. HONORABLE SECRETARY OF AGRARIAN REFORM)Document2 pagesCase Digest (ASSOCIATION OF SMALL LANDOWNERS IN THE PHILIPPINES, INC., ET AL. vs. HONORABLE SECRETARY OF AGRARIAN REFORM)Pearl GoNo ratings yet

- Draft Expropriation BillDocument61 pagesDraft Expropriation BillTiso Blackstar Group100% (1)

- Estate of Salud Jimenez Vs PEZADocument1 pageEstate of Salud Jimenez Vs PEZAErika Mariz CunananNo ratings yet

- Republic V Vda de Castellvi DigestDocument3 pagesRepublic V Vda de Castellvi DigestWazzupNo ratings yet

- DAR Rep by Sec. Hernani Braganza vs. Philippine Communications Satellite Corp. G.R. No. 152640, June 15, 2006Document9 pagesDAR Rep by Sec. Hernani Braganza vs. Philippine Communications Satellite Corp. G.R. No. 152640, June 15, 2006Dario NaharisNo ratings yet

- Gutierrez V Collector 101 Phil 743Document1 pageGutierrez V Collector 101 Phil 743Khian JamerNo ratings yet

- Secretary of DPWH v. Tecson GR No. 179334Document19 pagesSecretary of DPWH v. Tecson GR No. 179334Cyrus Pural EboñaNo ratings yet

- Republic vs. Court of AppealsDocument24 pagesRepublic vs. Court of Appealsericjoe bumagatNo ratings yet

- Admin Law Cases Pt. 1Document9 pagesAdmin Law Cases Pt. 1bayi88No ratings yet

- Philippine Constitution Article XIII, Section 4 Article III Section 9Document28 pagesPhilippine Constitution Article XIII, Section 4 Article III Section 9Emmanuel OrtegaNo ratings yet

- NPC V Tarcelo DigestDocument1 pageNPC V Tarcelo DigestLayaNo ratings yet

- Douglas County School Dist. No. 10 v. Tribedo, LLC, No. S-19-986 (Neb. Nov. 6, 2020)Document17 pagesDouglas County School Dist. No. 10 v. Tribedo, LLC, No. S-19-986 (Neb. Nov. 6, 2020)RHTNo ratings yet