Prevalence of Actinic Keratoses and Associated Factors in A Representative Sample of The Italian Adult Population

Prevalence of Actinic Keratoses and Associated Factors in A Representative Sample of The Italian Adult Population

Uploaded by

Bilqis KhaerunnisaCopyright:

Available Formats

Prevalence of Actinic Keratoses and Associated Factors in A Representative Sample of The Italian Adult Population

Prevalence of Actinic Keratoses and Associated Factors in A Representative Sample of The Italian Adult Population

Uploaded by

Bilqis KhaerunnisaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Prevalence of Actinic Keratoses and Associated Factors in A Representative Sample of The Italian Adult Population

Prevalence of Actinic Keratoses and Associated Factors in A Representative Sample of The Italian Adult Population

Uploaded by

Bilqis KhaerunnisaCopyright:

Available Formats

STUDY

Prevalence of Actinic Keratoses and Associated

Factors in a Representative Sample of the Italian

Adult Population

Results From the Prevalence of Actinic Keratoses Italian Study, 2003-2004

Luigi Naldi, MD; Liliane Chatenoud, ScD; Roberto Piccitto, MD; Paolo Colombo, ScD;

Elena Benedetti Placchesi, MPharm; Carlo La Vecchia, MD;

for the Prevalence of Actinic Keratoses Italian Study (PraKtis) Group

Objective: The Prevalence of Actinic Keratoses Italian ported that they did not receive therapy. Based on the

Study (PraKtis) was designed to estimate the point preva- interviewer’s judgment, the point prevalence of AKs was

lence of actinic keratoses (AKs) and associated factors in a 1.4% (95% confidence interval, 1.2%-1.8%). Forty-two

representative sample of the Italian adult population. percent of people with AKs were unaware of their con-

dition. The prevalence was higher among men than

Design: A representative sample of people 45 years or

women and increased steadily with age. The prevalence

older was selected from the electoral rolls according to a

stratified random sampling design. increased with lighter phenotype and with more severe

facial wrinkling. It also increased with the reported num-

Setting: A total of 180 specifically trained interviewers ber of hours spent in the sun during the week and on

contacted the sampled subjects and conducted face-to- holidays. No clear variation was observed according to

face, computer-assisted interviews and skin assessments. the reported use of sunscreens. Lesions were usually mul-

tiple (median number, 4). There was a strong associa-

Participants: A total of 12 483 subjects contacted and

tion between a history of nonmelanoma skin cancers and

interviewed from March 1, 2003, through April 30, 2004. the presence of AKs (odds ratio, 4.5; 95% confidence in-

Main Outcome Measures: History of AKs and evi- terval, 1.8-11.0).

dence of AKs at the interview.

Conclusions: The prevalence of AKs in our study was

Results: Overall, an estimated 34% of the Italian popu- remarkably lower than expected based on data from the

lation reported ever having undergone a dermatological United States and Australia; in Italy, AKs seem to be

examination. A history of AKs was reported by 0.3% of underdiagnosed and undertreated.

the total sample. Topical therapy was the most popular

treatment according to 39% of subjects, whereas 25% re- Arch Dermatol. 2006;142:722-726

A

CTINIC KERATOSES(AKS)ARE sex, sociodemographic variables and envi-

skinlesions,especiallycom- ronmental exposures; and describe treatment

mon in fair-complexioned modalities.15

Author Affiliations: people living in sunny cli-

Coordinating Center, Italian mates, which have been METHODS

Group for Epidemiological strongly associated with the risk of both basal

Research in Dermatology cell carcinoma and squamous cell carcino- A representative sample of people 45 years or

(GISED), Department of ma and are considered to be precursors (or older was selected according to a stratified ran-

Dermatology, Ospedali Riuniti, dom sampling design. Subjects were subse-

evenan early form) of invasive squamous cell

Bergamo, Italy (Drs Naldi and quently visited at their homes, where a face-

Placchesi); Laboratory of carcinoma.1-4In spite of being common, only to-face, computer-assisted personal interview

Epidemiology, Istituto di limited data on the epidemiology of AKs de- and skin examination were conducted.

Ricerche Farmacologiche Mario rived from country-based surveys are avail-

Negri, Milan, Italy able. Moreover, most studies have been con-

(Drs Chatenoud and La ducted in Australia or the United States, with SAMPLING PROCEDURE

Vecchia); Medical Direction 3M scanty datafrom most Europeancountries.5-14

Italia, Milan (Dr Piccitto); and The sampling procedure was envisaged in col-

Doxa, Milan (Dr Colombo).

The Prevalence of Actinic Keratoses Italian laboration with Doxa, the Italian branch of the

Group Information: A complete Study (PraKtis) was designed to estimate the Gallup International Association. The uni-

list of the PraKtis Study Group point prevalence of AKs in the Italian adult verse, or statistical population, to which the sur-

is given at the end of the article. population; assess variationsaccordingtoage, vey refers to was made up of all Italian adults,

(REPRINTED) ARCH DERMATOL/ VOL 142, JUNE 2006 WWW.ARCHDERMATOL.COM

722

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 11/07/2018

men and women 45 years or older. It was estimated that this STUDY POWER

universe was composed of about 24.8 million people (about

11.3 million men and 13.5 million women). The universe was In the first Health and Nutrition Examination Survey

subdivided into sections, or strata, according to 2 characteris- (NHANES I)5 conducted in the United States, the overall point

tics: region and size of community. The number of interviews prevalence increased from 15.9 per 1000 at ages 45 to 54 years

to be carried out in each stratum was set in proportion to the to 65.1 per 1000 at ages 65 to 74 years. It was calculated that with

distribution of the population of the strata in the area. Within a sample of about 12 000 subjects, estimates were sufficiently pre-

each stratum the sampling units (communities, districts of com- cise even for prevalence values as low as 1% (eg, expected preva-

munities, and individuals) were chosen in the following way: lence, 1%; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.7%-1.3%).

Stage 1: The choice concerned the communities or munici-

palities (sampling points where the interviews were to be con- DATA ANALYSIS

ducted).

Stage 2: In each municipality, an adequate number of elec- We obtained weighted estimates of the frequencies of selected

toral wards were extracted at random so that the various types items, taking into account the distribution of the Italian popu-

of inhabited areas of the community were represented in the lation. Initially, we calculated the point prevalence estimate of

right proportions. AKs and the associated 95% CI in the whole sample and in strata

Stage 3: The names and addresses of the persons to be in- of selected sociodemographic factors, phenotypic characteris-

terviewed were extracted at random from the electoral lists of tics, and sun exposure habits. Then, for analytical purposes, we

the wards selected in the second stage. calculated odds ratios as estimates of the relative risks for AKs

This method is known as a proportional stratified sample.16 and their 95% CIs. Unconditional multiple logistic regression with

We adopted a sampling with replacement procedure. maximum likelihood fitting models was applied to account for

potential simultaneous effect of selected factors (ie, age, sex, area

of residence, and phenotype).20

ASSESSMENT AND DATA COLLECTION

RESULTS

Specifically trained interviewers contacted the sampled sub-

jects and, after obtaining informed consent, conducted a face- From March 1, 2003, though April 30, 2004, a total of

to-face interview at the subject’s house using a computer-

assisted personal interviewing technique. The following set of

12 483 subjects were contacted and interviewed. Over-

information was collected: age; sex; occupation; smoking hab- all, a weighted estimate of 34% (29% of men and 38% of

its; skin, hair, and eye colors; degree of facial wrinkling; num- women) of the sample studied (n= 4232) reported ever

ber and distribution of suspected AKs on the face and upper having undergone a dermatological examination. A his-

limbs; previous diagnoses and/or treatment for AKs (with num- tory of AKs was reported by 0.3% of the total sample

ber, location, and modality of treatment); and previous diag- (n= 40, of which 26 [65%] were also recognized as hav-

noses of selected dermatological diseases. Skin color was evalu- ing had AKs by the interviewers). The most popular treat-

ated using a 3-grade scale (light, medium, and dark) based on ments for AKs in these subjects were, in order, pharma-

the examiner’s judgment and comparison with representative cological therapy (39%), treatment with liquid nitrogen

sample photographs. Judgment on hair color was made on a (23%), and curettage (11%). Twenty-five percent of sub-

5-category scale, and judgment on eye color was made on a 6-cat-

egory scale. A photonumeric scale was used to assess facial wrin-

jects reported that they had not received treatment.

kling, graded from 0 (none) to 8 (severe). 17-19 Actinic kerato- Based on the interviewer’s judgment, the point preva-

ses were evaluated with the help of a photographic atlas after lence of AKs was 1.4% (95% CI, 1.2%-1.8%). Forty-two

appropriate training (described in the next subsection). percent of patients with AKs, as classified by the inter-

Photographs of suspicious lesions were taken for further re- viewer, were unaware of their condition. The prevalence

view by an expert panel. To improve compliance, educational was higher among men (1.5%) than women (1.4%). It in-

materials on skin care were offered. creased with age from about 0.6% (45-54 years) up to 3.0%

(>74 years) (Table 1). Some variations were observed

according to the geographic area, with lower prevalence

INTERVIEWERS’ TRAINING SESSIONS rates in the center of Italy and higher rates in the islands

of Sicily and Sardinia (2.9%; 95% CI, 1.8%-4.6%). The

From February 1 through February 28, 2003, a total of 180

prevalence tended to be higher among people living in small

interviewers were trained. Training sessions were conducted

in the 10 Italian dermatological (PraKtis) centers collaborat- centers (Š10 000 inhabitants) compared with larger ones

ing in the study. A detailed presentation of the clinical fea- (y2 trend,19.8; P = .001) and in people of the lower socio-

tures of AKs and other common discrete skin lesions (eg, economic classes (y2 trend, 10.9; P = .001) (Table 1). The

seborrheic keratoses and solar lentigo) were presented in a prevalence increased with lighter phenotype, and the high-

2-hour teaching session. Using a specifically developed pho- est prevalence rate for severe facial wrinkling (3.2%; 95%

tographic atlas, interviewers also conducted practical exer- CI, 2.1%-5.0%) was observed in people with red or blond

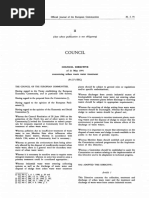

cises with a sample of subjects with and without selected hair (Table 2). The combined effect of age and skin phe-

skin lesions to improve the recognition of typical lesions and notype is shown in the Figure. The prevalence increased

to assess skin phenotype and degree of facial wrinkling. In with the reported number of hours spent in the sun on

preliminary exercises, involving subjects with AKs and sub-

jects without them, the interviewers’ assessment of AKs had weekdays (y2 trend, 14.0; P = .002) and during holidays

an average sensitivity of 63% and specificity of 79%. For the (y2 trend, 8.6; P = .003). We did not observe a clear varia-

purpose of this study, we defined AKs as discrete lesions tion according to the reported use of sunscreens (Table 3).

with ill-defined borders, dry surface, roughness on palpa- In subjects with AKs, usually more than 1 lesion was

tion, and color that varies from gray to red to reddish brown. counted, with a mean value of 10.5 and a median value of

(REPRINTED) ARCH DERMATOL/ VOL 142, JUNE 2006 WWW.ARCHDERMATOL.COM

723

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 11/07/2018

Table 1. Characteristics of Patients With Actinic Keratoses Table 2. Skin and Eye Characteristics of Patients

With Actinic Keratoses (AKs)

Cases, Prevalence, OR

Characteristic No. % (95% CI) (95% CI)* No. of AK Prevalence, OR

Characteristic AK Cases % (95% CI) (95% CI)*

Total 180 1.4 (1.2-1.8)

Sex Skin color†

Men 88 1.5 (1.2-1.8) 1.00 Fair or pale 89 2.1 (1.7-2.5) 1.00

Women 92 1.4 (1.1-1.7) 0.69 (0.51-0.93) Medium 75 1.2 (0.9-1.5) 0.53 (0.39-0.73)

Age, y† Dark or olive 16 0.7 (0.3-1.0) 0.32 (0.19-0.55)

45-54 21 0.6 (0.3-0.8) 1.00 Not evaluable 0

55-64 33 1.0 (0.6-1.3) 1.70 (0.98-2.95) Eyes color‡

65-74 79 2.2 (1.7-2.7) 4.07 (2.51-6.60) Black or brown 65 1.1 (0.8-1.4) 1.00

>74 46 3.0 (2.1-3.9) 5.26 (3.13-8.85) Light brown 54 1.5 (1.1-1.9) 1.26 (0.88-1.82)

Education, y or green-brown

Secondary school 32 0.9 (0.6-1.2) 1.00 Gray, green, or blue 60 2.0 (1.5-2.5) 1.62 (1.14-2.32)

and university (>8) Not evaluable 1

Intermediate school (6-8) 53 1.3 (0.9-1.6) 1.29 (0.82-2.02) Hair color§ Black

Primary school (Š5) 95 1.9 (1.5-2.3) 1.23 (0.80-1.91) or brown Light 74 0.9 (0.7-1.1) 1.00

Area of residence in Italy brown/red brown 76 2.1 (1.6-2.6) 2.44 (1.76-3.39)

Northwest 36 1.0 (0.7-1.3) 1.00 Blond or red 30 2.9 (1.9-3.9) 3.23 (2.09-5.00)

Northeast 45 1.9 (1.3-2.4) 1.88 (1.20-2.93) Not evaluable 0

Center 28 1.1 (0.7-1.5) 0.97 (0.59-1.61) Facial wrinkling score "

South 33 1.2 (0.8-1.6) 1.32 (0.82-2.14) <2 3 0.6 (0.0-1.3) 0.50 (0.15-1.67)

Islands (Sicily 37 2.9 (2.0-3.8) 2.94 (1.84-4.69) 2-5 77 1.1 (0.8-1.3) 0.91 (0.64-1.30)

and Sardinia) Š6 100 2.1 (1.7-2.5) 1.00

No. of inhabitants in town

of residence‡ Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

Š10 000 74 1.9 (1.5-2.3) 1.00 *Estimates from multiple logistic regression including terms for sex, age,

10 001-100 000 90 1.7 (1.3-2.0) 0.92 (0.67-1.26) and area of residence (for the facial wrinkling score, skin phenotype was also

>100 000 16 0.5 (0.2-0.7) 0.28 (0.16-0.48) included).

Socioeconomic class§ †y2 Trend, 24.4; P = .001.

High 3 1.7 (0.0-3.6) 1.00 ‡y2 Trend, 7.4; P = .007.

Middle 161 1.4 (1.2-1.6) 0.67 (0.21-2.12) §y2 Trend, 27.4; P = .001.

Low 16 3.9 (2.0-5.8) 1.48 (0.41-5.31) "y2 Trend, 10.8; P = .001.

Smoking habits

Nonsmoker 102 1.5 (1.2-1.8) 1.00

Smoker 27 0.9 (0.6-1.2) 0.83 (0.53-1.32)

Former smoker 51 1.7 (1.2-2.2) 0.93 (0.64-1.35) Fair or Pale Medium Dark or Olive

5

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; OR, odds ratio.

*Estimates from multiple logistic regression including, when appropriate, 4.1

terms for sex, age, area of residence, and skin phenotype. 4

†y2 Trend, 56.7; P = .001. 3.4

Prevalence, %

‡y2 Trend, 19.8; P = .001. 3

2.6

§y2 Trend, 10.9; P = .001.

2 1.9

1.2

1.0

1

0.6 0.7

4. A history of nonmelanoma skin cancers was reported 0.5

by 0.6% of the whole sample. There was a strong associa- 0

45-64 65-74 75

tion between such a history and the presence of AKs as

Age, y

judged by the interviewer; the age- and sex-adjusted odds

ratio was 4.5 (95% CI, 1.8-11.0).

Figure. Distribution of actinic keratoses (AKs) by age and skin type. The bars

show the prevalence of AKs in the Italian population by skin type (fair or

COMMENT pale, medium, and dark or olive) in 3 different age groups (45-64, 65-74, and

Š75 years). Prevalence values (per 100 people) are indicated above the

corresponding bars.

Our study provides information about the prevalence of

AKs in Italy. The study involved a complex proportional

stratified sampling design, and our estimates are prevalence for AKs in that study ranged from 15.9 per 1000

deemed to be representative of the whole Italian adult popu- at ages 45 to 54 years to 65.1 per 1000 at ages 65 to 74

lation (Š45 years). The prevalence in our study was re- years.5 These figures are roughly 3 time higher than ours.

markably lower than estimates obtained in other coun- To the best of our knowledge, only 3 studies provide es-

tries, such as the United States and Australia.5-14 It should timates from European countries. In a study12 conducted

be noted that most of the available studies covered in south Wales, involving 1034 subjects 60 years or older,

limited areas. The only study that was countrywide the prevalence of AKs was 23% (95% CI, 19.5%-26.5%).

and relied on a sampling design similar to ours is the In a study13 conducted in the Mersey region in northwest

NHANES I study5 conducted in the United States. The point England of people older than 40 years (531 men and 437

(REPRINTED) ARCH DERMATOL/ VOL 142, JUNE 2006 WWW.ARCHDERMATOL.COM

724

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 11/07/2018

ported ever receiving a diagnosis of the condition, and

Table 3. Sun Exposure and Sunscreen Use by Patients as many as 25% of people with a history of AKs did not

With Actinic Keratoses (AKs) undergo any therapeutic procedure for the disease. In the

United States, it was documented that only 40% of phy-

Cases, AK Prevalence, OR

Characteristic No. % (95% CI) (95% CI)*

sicians who were aware of AKs treated the condition.24

The need to treat AKs is debatable, and a lively debate

Sun exposure during

exists about whether AKs should be actually considered

weekdays, h†

<2 23 1.1 (0.6-1.5) 1.00 and treated as early squamous cell carcinoma.25,26 From an

2 18 0.7 (0.4-1.0) 0.83 (0.44-1.54) epidemiological point of view, it has been estimated that

3-4 48 1.5 (1.1-1.9) 1.91 (1.13-3.21) the transformation rate of individual lesions is less than 1

Š5 62 1.8 (1.3-2.2) 2.17 (1.29-3.65) in 1000 per year27 and that the lifetime risk of invasive squa-

Days of sun exposure mous cell carcinoma developing in an individual with AKs

during holidays‡

<8 27 1.0 (0.6-1.4)

1.00 is these

of 10%.12,28

6% tolesions in In

theaddition, a remarkable

general population hasturnover rate

been docu-

8-19 23 1.0 (0.6-1.4) 1.43 (0.81-2.54)

20-39 22 0.9 (0.5-1.3) 1.30 (0.73-2.32) mented with high incidence and spontaneous regression

Š40 51 1.9 (1.4-2.4) 2.12 (1.31-3.45) rates.29 Actinic keratoses appear more frequently as mul-

Use of sunscreens tiple lesions and are associated with a higher risk of devel-

Usually 42 1.1 (0.8-1.4) 1.00

0.88 (0.52-1.51)

oping nonmelanoma skin cancers as indicated by our sur-

Sometimes 21 1.0 (0.6-1.4) 1.12 (0.77-1.65) vey. Preventive treatment of cancer-prone areas with sun

Occasionally or never 116 1.8 (1.5-2.1) protection30 and topical agents seems to represent a more

Abbreviations: CI, confidenc e interval; OR, odds ratio. reasonable option than destructive procedures performed

*Estimates from multiple logistic regression including terms for sex, age, on individual lesions. In our study, we were unable to docu-

area of residence, and phenotype score. ment a protective effect from the use of sunscreens, but the

†y2 Trend, 14.0; P = .002. percentage of people using sunscreens in the whole popu-

‡y2 Trend, 8.6; P = .003.

lation was notably low (about 30%).

In conclusion, the prevalence of AKs in Italy was con-

siderably lower than the prevalence in the United States

women) treated at outpatient (nondermatology) clinics, and Australia. Age, skin phenotype, and sun exposure were

the prevalence of AKs was 15.4% in men and 5.9% in strongly associated with the prevalence of these lesions;

women. In another study,14 conducted in the community they seem to be underdiagnosed and undertreated in our

of Freixo de Espada à Cinta in northeast Portugal, AKs were population.

identified in 9.6% of subjects, and no relation was docu-

mented between skin phenotype and AKs. Interestingly, Accepted for Publication: April 26, 2005.

AKs were diagnosed in 3.6% of 190 adults treated at a can- Correspondence: Luigi Naldi, MD, Centro Studi GISED,

cer prevention program in Rome.21 There are many rea- Clinica Dermatologica, Ospedali Riuniti di Bergamo, Largo

sons for the discrepancies between our data and those ob- Barozzi 1, 24128 Bergamo, Italy (luigi.naldi@gised.it).

tained in other studies. The method used to collect Author Contributions: Study concept and design: Naldi, La

information in our survey may be of concern because we Vecchia, Piccitto, and Colombo. Acquisition of data:

relied on evaluations by interviewers who, even though Colombo and Placchesi. Analysis and interpretation of data:

they had been trained, may have missed or misclassified La Vecchia, Chatenoud, and Naldi. Drafting of the manu-

cases. However, in preliminary exercises, the perfor- script: Naldi. Critical revision of the manuscript for impor-

mance of interviewers in correctly classifying cases of AKs tant intellectual content: La Vecchia and Piccitto. Statistical

was judged to be satisfactory. In addition, we were un- analysis: Colombo and Chatenoud. Obtained funding:

able to document large discrepancies between interview- Piccitto. Administrative, technical, and material support:

ers in case identification. Placchesi. Study supervision: Naldi and La Vecchia.

As expected,6,7,12,13 the prevalence of AKs was higher Group Members: Collaborators of the PraKtis Study

in men than women. It increased significantly with age, Group: Unità Operativa Dermatologia, Ospedali Ri-

with increased number of hours spent in the sun during uniti, Bergamo, Italy (A. Reseghetti, MD); Clinica Der-

weekdays and on holidays, and with more severe signs matologica, Università Cagliari (A. L. Pinna, MD, and L.

of purported skin photodamage (ie, facial wrinkles); and Atzori, MD); Clinica Dermatologica, Università Catania

it was higher in people with a lighter skin phenotype. Ac- (G. Micali, MD, and M. L. Musumeci, MD); Clinica Der-

tually, differences in prevalent skin phenotype, lati- matologica, Università Chieti (C. Feliciani, MD); Osped-

tude, and sun exposure habits may explain, at least partly, ale Cà Granda Niguarda, Milano (I. Stanganelli, MD, and

the differences in prevalence between our study and simi- M. Locatelli, MD); Ambulatorio di Dermatologia, Napoli

lar surveys in other countries. Interestingly, the preva- Azienda Sanitaria Locale (A. Aurilia, MD, and P. Raiola,

lence of AKs in Japan is considerably lower than the one MD); Clinica Dermatologica, Università Padova (S.

we reported, ranging from 0.2% to 0.7%.8-10 Piaserico, MD); Arcispedale Santa Maria Nuova, Reggio

In agreement with other surveys in Europe and the Emilia (G. Lo Scocco, MD, and A. Bonci, MD); Clinica

United States,22,23 the level of awareness about AKs in the Dermatologica, Policlinico Tor Vergata, Roma (S.

general population of Italy was rather low; 42% of sub- Chimenti, MD, and E. Campione, MD); Ospedale S. Paolo,

jects with AKs were unaware of their skin lesions. Only Savona (A. Farris, MD, and A. Pestarino, MD); Istituto

about 25% of all the subjects with AKs interviewed re- S. Gallicano, Roma (L. Eibenschutz, MD, and C. Catricalà,

(REPRINTED) ARCH DERMATOL/ VOL 142, JUNE 2006 WWW.ARCHDERMATOL.COM

725

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 11/07/2018

MD); Ospedale Principale Militare, Taranto (V. Cantoro, 14. Massa A, Alves R, Amado J, et al. Prevalence of cutaneous lesions in Freixo de

Espada a Cinta. Acta Med Port. 2000;13:247-254.

MD, and V. Ingordo, MD); Clinica Dermatologica, Uni- 15. Naldi L, Colombo P, Placchesi EB, Piccitto R, Chatenoud L, La Vecchia C; PraKtis

versità Verona (A. Barba, MD, and G. Tessari, MD); and Study Centers. Study design and preliminary results from the pilot phase of the

Clinica Dermatologica S. Lazzaro, Università Torino (M. PraKtis study: self-reported diagnoses of selected skin diseases in a represen-

tative sample of the Italian population. Dermatology. 2004;208:38-42.

Pippione, MD, and D. Albertazzi, MD). 16. Levy PS, Lemeshow S. Sampling for Health Professionals. Belmont, Calif: Life-

Financial Disclosure: None. time Learning Publications; 1980.

Funding/Support: This study was supported by a 17. Naldi L, Imberti GL, Parazzini F, Gallus S, La Vecchia C. Pigmentary traits, mo-

dalities of sun reaction, history of sunburns, and melanocytic nevi as risk fac-

research grant from the 3M Foundation. tors for cutaneous malignant melanoma in the Italian population: results of a col-

laborative case-control study. Cancer. 2000;88:2703-2710.

REFERENCES 18. Naldi L, DiLandro A, D’Avanzo B, Parazzini F. Host-related and environmental

risk factors for cutaneous basal cell carcinoma: evidence from an Italian case-

control study. J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:446-452.

1. Preston DS, Stern RS. Non-melanoma cancers of the skin. N Engl J Med. 1992; 19. Carli P, Naldi L, Lovati S, et al. The density of melanocytic nevi correlates with

327:1649-1662. constitutional variables and history of sunburns: a prevalence study among Ital-

2. Sober AJ, Burstein JM. Precursors to skin cancer. Cancer. 1995;75:645-650. ian schoolchildren. Int J Cancer. 2002;101:375-379.

3. Frost CA, Green AC. Epidemiology of solar keratoses. Br J Dermatol. 1994;131: 20. Breslow NE, Day NE. Statistical Methods in Cancer Research . Lyon, France: IARC

455-464. Science Publications; 1980. The Analysis of Case-Control Studies; Vol. 1. No. 32.

4. Lebwohl M. Actinic keratosis: epidemiology and progression to squamous cell 21. Lacava V, Salesi N, Ferrone L, et al. Importance of dermatologic screening within

carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2003;149(suppl):31-33. the framework of a general cancer prevention program. Minerva Med. 2001;

5. Johnson M-LT, Roberts J. Skin Conditions and Related Need for Medical Care 92:85-88.

Among Persons 1-74 Years. Hyattsville, Md: US Department of Health, Educa- 22. Berman B. Basal cell carcinoma and actinic keratoses: patients’ perceptions of

tion, and Welfare; 1978. the disease and current treatment. Int J Dermatol. 2001;40:573-576.

6. Marks R, Ponsford MW, Selwood TS, Goodman G, Mason G. Non-melanotic skin 23. MacKie RM. Awareness, knowledge and attitudes to basal cell carcinoma and

cancer and solar keratoses in Victoria. Med J Aust. 1983;2:619-622.

actinic keratoses among the general public within Europe. J Eur Acad Dermatol

7. Vitasa BC, Taylor HR, Strickland PT, et al. Association of nonmelanoma skin can-

Venereol. 2004;18:552-555.

cer and actinic keratosis with cumulative solar ultraviolet exposure in Maryland

24. Halpern AC, Hanson LJ. Awareness of, knowledge and attitudes to nonmela-

watermen. Cancer. 1990;65:2811-2817.

8. Suzuki T, Ueda M, Naruse K, et al. Incidence of actinic keratosis of Japanese in noma skin cancer (NMSC) and actinic keratosis (AK) among physicians. Int J

Kasai City, Hyogo. J Dermatol Sci. 1997;16:74-78. Dermatol. 2004;43:638-642.

9. Naruse K, Ueda M, Nagano T, et al. Prevalence of actinic keratosis in Japan. 25. Cockerell CJ. Histopathology of incipient intraepidermal squamous cell carci-

J Dermatol Sci. 1997;15:183-187. noma (“actinic keratosis”). J Am Acad Dermatol. 2000;42:11-17.

10. Nagano T, Ueda M, Suzuki T, et al. Skin cancer screening in Okinawa, Japan. 26. Flaxman BA. Actinic keratoses: malignant or not? J Am Acad Dermatol. 2001;45:

J Dermatol Sci. 1999;19:161-165. 466-467.

11. Araki K, Nagano T, Ueda M, et al. Incidence of skin cancers and precancerous lesions 27. Marks R, Rennie G, Selwood TS. Malignant transformation of solar keratoses to

in Japanese: risk factors and prevention. J Epidemiol. 1999;9(6)(suppl):S14-21. squamous cell carcinoma. Lancet. 1988;1:795-797.

12. Harvey I, Frankel S, Marks R, Shalom D, Nolan-Farrell M. Non-melanoma skin 28. Glogau RG. The risk of progression to invasive disease. J Am Acad Dermatol.

cancer and solar keratoses, I: methods and descriptive results of the South Wales 2000;42:23-24.

Skin Cancer Study. Br J Cancer. 1996;74:1302-1307. 29. Frost C, Williams G, Green A. High incidence and regression rates of solar kera-

13. Memon AA, Tomenson JA, Bothwell J, Friedmann PS. Prevalence of solar dam- toses in a Queensland community. J Invest Dermatol. 2000;115:273-277.

age and actinic keratosis in a Merseyside population. Br J Dermatol. 2000; 30. Thompson SC, Jolley D, Marks R. Reduction of solar keratoses by regular sun-

142:1154-1159. screen use. N Engl J Med. 1993;329:1147-1151.

(REPRINTED) ARCH DERMATOL/ VOL 142, JUNE 2006 WWW.ARCHDERMATOL.COM

726

©2006 American Medical Association. All rights reserved.

Downloaded From: on 11/07/2018

You might also like

- For TranslateDocument2,012 pagesFor TranslateAlexandro Fernandes de SousaNo ratings yet

- Jack D. Douglas-Understanding Everyday Life - Toward The Reconstruction of Sociological Knowledge-Aldine Pub. Co (1970) PDFDocument363 pagesJack D. Douglas-Understanding Everyday Life - Toward The Reconstruction of Sociological Knowledge-Aldine Pub. Co (1970) PDFAlenka Švab75% (4)

- Desta AlcoholDocument76 pagesDesta AlcoholMULAT DEGAREGENo ratings yet

- Consequences of Acne On Stress, Fatigue, Sleep Disorders and Sexual Activity: A Population-Based StudyDocument4 pagesConsequences of Acne On Stress, Fatigue, Sleep Disorders and Sexual Activity: A Population-Based StudyerinNo ratings yet

- 2010 - Epidemioloy of Ulcerative Keratitis in Northern CaliforniaDocument7 pages2010 - Epidemioloy of Ulcerative Keratitis in Northern CaliforniaPrasetya AnugrahNo ratings yet

- Worldwide Incidence of Odontogenic Tumors.27Document6 pagesWorldwide Incidence of Odontogenic Tumors.27larissaNo ratings yet

- Ferrucci 2014Document6 pagesFerrucci 2014Bobby JimNo ratings yet

- Worldwide Incidence of Odontogenic Tumors.27Document6 pagesWorldwide Incidence of Odontogenic Tumors.27larissaNo ratings yet

- All 13401Document10 pagesAll 13401hahihouNo ratings yet

- Epidemiologic Study of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: A Systematic ReviewDocument10 pagesEpidemiologic Study of Charcot-Marie-Tooth Disease: A Systematic ReviewFelipe Palma UrrutiaNo ratings yet

- NCM 112 Trinal 9Document6 pagesNCM 112 Trinal 9Marielle ChuaNo ratings yet

- M CAD Ermatol CtoberDocument1 pageM CAD Ermatol CtoberFerdie YuzonNo ratings yet

- Piis107858840500331xDocument8 pagesPiis107858840500331xSahar UntadNo ratings yet

- Incidence and Prevalence of Salivary Glands Tumors in Valparaíso, ChileDocument8 pagesIncidence and Prevalence of Salivary Glands Tumors in Valparaíso, ChileJAVIERA HIDALGONo ratings yet

- Screening For Thyroid Diseases AmongDocument4 pagesScreening For Thyroid Diseases AmongDr. Saeed BafarajNo ratings yet

- Detection of Cervical SmearsDocument4 pagesDetection of Cervical Smearsvyvie89No ratings yet

- Communicable Disease Surveillance: OfepidemiologyDocument4 pagesCommunicable Disease Surveillance: OfepidemiologyMuhammad Hafiidh MuizzNo ratings yet

- PsoriasisDocument8 pagesPsoriasisJocelyn Dunstan EscuderoNo ratings yet

- 5713-Article Text-37292-1-10-20201030Document5 pages5713-Article Text-37292-1-10-20201030Indermeet Singh AnandNo ratings yet

- Epidemiologia ComunitariaDocument4 pagesEpidemiologia Comunitariaalexis joaquin vargasNo ratings yet

- Cleusa P Ferri Martin Prince Carol Brayne Henry Brodaty Laura Fratiglioni Mary Ganguli Kathleen Hall Kazuo Hasegawa Hugh HendrieDocument6 pagesCleusa P Ferri Martin Prince Carol Brayne Henry Brodaty Laura Fratiglioni Mary Ganguli Kathleen Hall Kazuo Hasegawa Hugh Hendrieabdillah u. djawahirNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 EPIDEMIOLOGICAL STUDIESDocument63 pagesChapter 4 EPIDEMIOLOGICAL STUDIESWagaw TesfawNo ratings yet

- Hta Ecv Lash M1 L1 RB1Document5 pagesHta Ecv Lash M1 L1 RB1Erick Méndez RodríguezNo ratings yet

- 2014 LeprosyDocument5 pages2014 LeprosySejal ThakkarNo ratings yet

- Risk Factors For Epilepsy in Rural Lao PDR: A Case-Control StudyDocument6 pagesRisk Factors For Epilepsy in Rural Lao PDR: A Case-Control StudylilingNo ratings yet

- Hahn El 2016Document9 pagesHahn El 2016ka waiiNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology in A Nutshell NCI BenchmarksDocument8 pagesEpidemiology in A Nutshell NCI BenchmarksThe Nutrition Coalition100% (1)

- BR J Dermatol - 2012 - Lomas - A Systematic Review of Worldwide Incidence of Nonmelanoma Skin CancerDocument12 pagesBR J Dermatol - 2012 - Lomas - A Systematic Review of Worldwide Incidence of Nonmelanoma Skin CancerJúnior MesquitaNo ratings yet

- European Consensus For The Management of Patients With Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma of The Follicular EpitheliumDocument17 pagesEuropean Consensus For The Management of Patients With Differentiated Thyroid Carcinoma of The Follicular Epitheliumelibet87No ratings yet

- Fistula Ani Japanese GuidelineDocument7 pagesFistula Ani Japanese GuidelinevivianmtNo ratings yet

- Guerchet 2012 RCA RC EDACDocument6 pagesGuerchet 2012 RCA RC EDACkouame2907No ratings yet

- A Systematic Review of Secretory Carcinoma of The Salivary Gland: Where Are We?Document10 pagesA Systematic Review of Secretory Carcinoma of The Salivary Gland: Where Are We?Uriel EnriquezNo ratings yet

- Pi Is 1087002416300296Document5 pagesPi Is 1087002416300296Ro KohnNo ratings yet

- LSHTM Study Designs NOTES LSTHMDocument39 pagesLSHTM Study Designs NOTES LSTHMKELVIN MAYOMBONo ratings yet

- Villa Maria - 2016Document10 pagesVilla Maria - 2016Rafael IribarrenNo ratings yet

- Review: Lucia Romani, Andrew C Steer, Margot J Whitfeld, John M KaldorDocument8 pagesReview: Lucia Romani, Andrew C Steer, Margot J Whitfeld, John M KaldorMuhammad AmrullahNo ratings yet

- Lipomas of Head and Neck: Original Research ArticleDocument4 pagesLipomas of Head and Neck: Original Research ArticlePleșcuță SimonaNo ratings yet

- Body Piercing and Tattoos: A Survey On Young Adults ' Knowledge of The Risks and Practices in Body ArtDocument8 pagesBody Piercing and Tattoos: A Survey On Young Adults ' Knowledge of The Risks and Practices in Body ArtIliana StrahilovaNo ratings yet

- Burden, Pattern, Associated Factors and Impact On Quality of Life of Dermatological Disorders Among The Elderly in Ilala Municipality, Dar Es Salaam A Cross-Sectional StudyDocument10 pagesBurden, Pattern, Associated Factors and Impact On Quality of Life of Dermatological Disorders Among The Elderly in Ilala Municipality, Dar Es Salaam A Cross-Sectional StudyInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Cacciatore 1999Document6 pagesCacciatore 1999Cams NormandiaNo ratings yet

- Profile of Tinea Corporis and Tinea Cruris in Dermatovenereology Clinic of Tertiery Hospital: A Retrospective StudyDocument6 pagesProfile of Tinea Corporis and Tinea Cruris in Dermatovenereology Clinic of Tertiery Hospital: A Retrospective StudyRose ParkNo ratings yet

- Trichotillomania and Skin-Picking DisorderDocument8 pagesTrichotillomania and Skin-Picking DisorderegosuspensionNo ratings yet

- Hydatid Disease of Central Nervous System, A Clinicopathological Study of 33 CasesDocument5 pagesHydatid Disease of Central Nervous System, A Clinicopathological Study of 33 CasesIvory Arévalo ManríquezNo ratings yet

- Fetch ObjectDocument12 pagesFetch ObjectJoel FlosanNo ratings yet

- Radiological Features of AIDS-related Pneumocystis Jiroveci InfectionDocument3 pagesRadiological Features of AIDS-related Pneumocystis Jiroveci InfectionJavi MontañoNo ratings yet

- A Disease of Western CivilizationDocument7 pagesA Disease of Western Civilizationrinad alhessiNo ratings yet

- An International Survey of Physician Attitudes and Practice in Regard To Revealing The Diagnosis of CancerDocument4 pagesAn International Survey of Physician Attitudes and Practice in Regard To Revealing The Diagnosis of Cancerm.pernetasNo ratings yet

- Acne Vulgaris in Adult Females Racial Differences I - 2013 - Journal of The AmeDocument1 pageAcne Vulgaris in Adult Females Racial Differences I - 2013 - Journal of The AmeDuy Nguyễn ĐứcNo ratings yet

- CHSJ 46 01 01Document6 pagesCHSJ 46 01 01Dragos AlexandruNo ratings yet

- Advance Epi & Direct Acyclic GraphDocument14 pagesAdvance Epi & Direct Acyclic GraphPurnima VermaNo ratings yet

- Development and Validation of The Quality of Life.39 PDFDocument5 pagesDevelopment and Validation of The Quality of Life.39 PDFTeiza NabilahNo ratings yet

- V32n3a07 217-25Document9 pagesV32n3a07 217-25Tejinder SinghNo ratings yet

- Original ArticleDocument7 pagesOriginal ArticleDain 2IronfootNo ratings yet

- Profile of Tinea Corporis and Tinea Cruris in Dermatovenereology Clinic of Tertiery Hospital: A Retrospective StudyDocument6 pagesProfile of Tinea Corporis and Tinea Cruris in Dermatovenereology Clinic of Tertiery Hospital: A Retrospective StudyMarwiyahNo ratings yet

- The Panama Aging Research Initiative Longitudinal Study: Lessons From The FieldDocument5 pagesThe Panama Aging Research Initiative Longitudinal Study: Lessons From The FieldMiguel Ángel DominguezNo ratings yet

- Thesis Jessica KattanDocument45 pagesThesis Jessica Kattanaztigan100% (2)

- Introduction To EpidemiologyDocument25 pagesIntroduction To EpidemiologyReza Alfitra MutiaraNo ratings yet

- Mall On 2000Document5 pagesMall On 2000Meta SakinaNo ratings yet

- Research On CancerDocument11 pagesResearch On Cancerrubyshah886No ratings yet

- Global Maps of Non-Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury Epidemiology: Towards A Living Data RepositoryDocument13 pagesGlobal Maps of Non-Traumatic Spinal Cord Injury Epidemiology: Towards A Living Data RepositoryiqbalNo ratings yet

- The International System for Serous Fluid CytopathologyFrom EverandThe International System for Serous Fluid CytopathologyAshish ChandraNo ratings yet

- Chimerism: A Clinical GuideFrom EverandChimerism: A Clinical GuideNicole L. DraperNo ratings yet

- Penus, Eliand John N. Week 7-8 Factors Affecting Chemical ReactionsDocument3 pagesPenus, Eliand John N. Week 7-8 Factors Affecting Chemical ReactionsGoogle AccountNo ratings yet

- Iball-Wireless Access Point SetupDocument109 pagesIball-Wireless Access Point Setupspgs1No ratings yet

- Oxford AQA GCSE History (9-1) Conflict and Tension First World War 1894-1918Document10 pagesOxford AQA GCSE History (9-1) Conflict and Tension First World War 1894-1918Amelie SummerNo ratings yet

- Substation Class 1-PPT 2003Document43 pagesSubstation Class 1-PPT 2003Md. Biplob HossainNo ratings yet

- Impact Panel Printer For Industrial Use: CharacteristicsDocument3 pagesImpact Panel Printer For Industrial Use: CharacteristicsWALTER DANIEL GUTIERREZ VEREAUNo ratings yet

- General Chemistry 2 NotesDocument31 pagesGeneral Chemistry 2 NoteshannahdurogaNo ratings yet

- Quadrilaterals IntroductionDocument19 pagesQuadrilaterals IntroductionBeajoy ManalangNo ratings yet

- Assignment Brand MGT ChevroletDocument13 pagesAssignment Brand MGT ChevroletManpreet Kaur SekhonNo ratings yet

- Examen 2Document12 pagesExamen 2Emily HurtadoNo ratings yet

- 2412.20073v1Document13 pages2412.20073v1yusufNo ratings yet

- Perhitungan Kebutuhan Oli KB 2-2Document15 pagesPerhitungan Kebutuhan Oli KB 2-2Angga Budi PratamaNo ratings yet

- Design For A Terminal Railw Ay Station: Frank T. Kegley, JRDocument13 pagesDesign For A Terminal Railw Ay Station: Frank T. Kegley, JRUsman FarooqNo ratings yet

- Alto APM80.1000, APM80.1500 Powered Mixer Service ManualDocument45 pagesAlto APM80.1000, APM80.1500 Powered Mixer Service Manualgustavo100% (4)

- Logistics and Intermodal Transport - CHAPTER 6 & 7Document89 pagesLogistics and Intermodal Transport - CHAPTER 6 & 7dinoquynh1No ratings yet

- Danelec Dm-800e EcdisDocument4 pagesDanelec Dm-800e EcdisAto ToaNo ratings yet

- Ucsi University B.Eng (Hons) in Chemical Engineering Course OutlineDocument2 pagesUcsi University B.Eng (Hons) in Chemical Engineering Course OutlinetkjingNo ratings yet

- V-Pin Connectors: Specification SheetDocument2 pagesV-Pin Connectors: Specification SheetCarlos FernandezNo ratings yet

- Hitachi EX2500-5 - Workshop ManualDocument518 pagesHitachi EX2500-5 - Workshop ManualUnurbat ByambajavNo ratings yet

- TLE LAS Cookery 10 Quarter 4 Week 2Document6 pagesTLE LAS Cookery 10 Quarter 4 Week 2Edgar Razona100% (1)

- Lev Semenovich PontryaginDocument4 pagesLev Semenovich PontryaginPaul J. FeldmanNo ratings yet

- Ili9341 An V0.4 20101227Document18 pagesIli9341 An V0.4 20101227erlonbr.olivNo ratings yet

- Celex 31991l0271 enDocument13 pagesCelex 31991l0271 enMila DautovicNo ratings yet

- Lesson 2&3 - Ancient Science & Developments of Science in Asia and PhilippinesDocument3 pagesLesson 2&3 - Ancient Science & Developments of Science in Asia and PhilippinesStanley AquinoNo ratings yet

- Meter Reading Details: Assam Power Distribution Company LimitedDocument1 pageMeter Reading Details: Assam Power Distribution Company LimitedPeakit SangmaNo ratings yet

- Application Form For Water & Sewer 2017Document4 pagesApplication Form For Water & Sewer 2017ywon nay chi lwinNo ratings yet

- Mobility Training Programs For Sports Performance: Training Articles Sean CochranDocument4 pagesMobility Training Programs For Sports Performance: Training Articles Sean CochranAnonymous PDEpTC4No ratings yet

- CV Imran Parvez MS-Aug2018Document6 pagesCV Imran Parvez MS-Aug2018Imran Parvez KhanNo ratings yet