Professional Development

Uploaded by

Kuko sa paaProfessional Development

Uploaded by

Kuko sa paaPOLICY BRIEF RESEARCH BRIEF MAY

APRIL2017

2016

Effective Teacher

Title

Professional Development

Linda Darling-Hammond, Maria E. Hyler, and Madelyn Gardner, with assistance from Danny Espinoza

Abstract Introduction

Teacher professional learning is of Teacher professional learning is of increasing interest as a critical way to

increasing interest as one way to

support the increasingly complex

support the increasingly complex skills students need to learn in order to

skills students need to succeed in succeed in the 21st century. Sophisticated forms of teaching are needed to

the 21st century. However, many develop student competencies such as deep mastery of challenging content,

teacher professional development critical thinking, complex problem solving, effective communication and

initiatives appear ineffective in

supporting changes in teacher collaboration, and self-direction. In turn, effective professional development

practices and student learning. To (PD) is needed to help teachers learn and refine the instructional strategies

identify the features of effective required to teach these skills.

professional development, this

paper reviews 35 methodologically However, research has noted that many professional development initiatives

rigorous studies that have appear ineffective in supporting changes in teachers’ practices and student

demonstrated a positive link

between teacher professional

learning. Accordingly, we set out to discover the features of effective

development, teaching practices, professional development. We define effective PD as structured professional

and student outcomes. It identifies learning that results in changes to teacher practices and improvements in

features of these approaches student learning outcomes.

and offers descriptions of these

models to inform those seeking to The paper on which this brief is based reviews methodologically rigorous

understand how to foster successful

studies that have demonstrated a positive link between teacher professional

strategies.

development, teaching practices, and student outcomes. To define features of

The full report can be found online

effective PD, we reviewed 35 studies from the last three decades that featured a

at https://learningpolicyinstitute.

org/product/teacher-prof-dev. careful experimental or comparison group design, or analyzed student outcomes

with statistical controls for context variables and student characteristics. We

External Reviewers coded each of the studies to identify the elements of effective professional

This report benefited from development models.

the insights and expertise of

two external reviewers: Laura

Desimone, Associate Professor, Elements of Effective Professional Development

Education Policy, Penn Graduate

School of Education; and Michael Using this methodology, we found seven widely shared features of effective

Fullan, former Dean of the Ontario professional development. Such professional development:

Institute for Studies in Education,

University of Toronto. We thank 1. Is content focused

them for the care and attention

2. Incorporates active learning utilizing adult learning theory

they gave the report. Any remaining

shortcomings are our own. 3. Supports collaboration, typically in job-embedded contexts

4. Uses models and modeling of effective practice

5. Provides coaching and expert support

The S. D. Bechtel, Jr. Foundation

and the Sandler Foundation have 6. Offers opportunities for feedback and reflection

provided operating support for the 7. Is of sustained duration

Learning Policy Institute’s work in

this area.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | RESEARCH BRIEF 1

Our research shows that effective professional learning experiences typically incorporate most or

all of these elements, as suggested in the examples below. Each of these elements was part of the

professional development addressed in at least 30 of the 35 studies we reviewed, and some were

featured in all 35.

Content Focus

Professional development that focuses on teaching

strategies associated with specific curriculum Professional development that

content supports teacher learning within their focuses on teaching strategies

classroom contexts. As one example, the

Science Teachers Learning from Lesson Analysis associated with specific

program (STeLLA) seeks to strengthen teachers’ curriculum content supports

understanding of how to teach science productively.

teacher learning within their

Its first goal is to deepen teacher understanding of

students’ science thinking, which helps teachers classroom contexts.

anticipate and respond to students’ ideas and

misunderstandings in productive ways. Its second

goal is to help teachers learn to sequence science ideas to help students construct a coherent “story”

that makes sense to them.

Over the course of more than 100 hours, STeLLA teachers studied and discussed video cases of

teaching, including student work and teacher interviews. They also taught model lessons themselves

and analyzed their teaching with their colleagues, evaluating the experience and student work to revise

the lessons for colleagues to then teach in a form of lesson study. These teachers’ students achieved

significantly greater learning gains on science pre- and post-tests than comparison students whose

teachers received content training only,1 a finding further confirmed by a second randomized study of the

program several years later.2

Active Learning

Active learning provides teachers with opportunities to get hands-on experience designing and practicing

new teaching strategies. In PD models featuring active learning, teachers often participate in the same

style of learning they are designing for their students, using real examples of curriculum, student work, and

instruction. For example, Reading Apprenticeship is an inquiry-based PD model designed to help high school

biology teachers integrate literacy and biology instruction in their classrooms. Each of the program’s 10 full-

day sessions is designed to immerse the teachers in the types of learning activities and environments they

will then be creating for their students. Working together, teachers study student work, videotape classroom

lessons for analysis, and scrutinize texts to identify potential literacy challenges to learners.

Teachers in the program practice classroom routines that will help to build student engagement and

student collaboration, such as “think-pair-share,” jigsaw groups, and text annotation. Reflection and other

metacognitive routines such as think-alouds and reading logs for science investigations are also used

in PD sessions. In a randomized control study in a set of high-poverty schools, this active learning PD

model resulted in student reading achievement gains equivalent to a year’s additional growth compared

with control group students, as well as significantly higher achievement on state assessments in English

language arts and biology.3

Collaboration

High-quality professional development creates space for teachers to share ideas and collaborate in their

learning, often in job-embedded contexts that relate new instructional strategies to teachers’ students

and classrooms. By working collaboratively, teachers can create communities that positively change the

L EARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | RESEARCH BRIEF 2

culture and instruction of their entire grade level, department, school, and/or district. “Collaboration” can

span a host of configurations—from one-on-one or small group collaboration to schoolwide collaboration

to collaboration with other professionals beyond the school.

In one program in a Texas district, teachers engaged in on-site, small-group professional development to

promote inquiry-based, literacy-integrated instruction in science classrooms to improve English language

learners’ science and reading achievement. Through the initiative, teachers and paraprofessionals

participated in collaborative biweekly workshops in which they jointly reviewed upcoming lessons, discussed

science concepts with peers, engaged in reflections on their students’ learning, and participated as learners

in the types of inquiry-based science activities they would be implementing for their students. They also

received instruction in strategies for teaching English language learners. Students who received enhanced

instructional activities and whose teachers received PD demonstrated significantly higher science and

reading achievement than students who were engaged in business-as-usual instruction.4 By focusing on

improving the practice of teachers of English language learners, this kind of collaborative, districtwide PD

can have important implications for improving the equity of whole systems.

Use of Models and Modeling

Curricular models and modeling of instruction

provide teachers with a clear vision of what best Curricular models and modeling of

practices look like. Teachers may view models that

instruction provide teachers with a

include lesson plans, unit plans, sample student

work, observations of peer teachers, and video or clear vision of what best practices

written cases of accomplished teaching. look like.

For example, in a program used across a number

of states, PD focused on the types of pedagogical

content knowledge teachers need to effectively teach elementary science. Curricular and instructional

models were used in multiple ways to support teacher learning. For example, one group of teachers

analyzed teaching cases drawn from actual classrooms and written by teachers. Another set of teachers

worked in carefully structured, collaborative groups to analyze examples of student work from a shared

unit taught in their own classrooms. A third group used metacognitive strategies to reflect on their

instruction and its outcomes. Teachers also had access to a “task bank” of formative assessment model

items they could use with their students during the program.

These types of models support teachers’ ability to “see” what good practices look like and implement new

strategies in their classrooms. In a randomized experimental study, students of teachers who participated

in any of these PD opportunities had significantly greater learning gains on science tests than students

whose teachers did not participate, and these effects were maintained a year later.5

Coaching and Expert Support

Coaching and expert support involve the sharing of expertise about content and practice focused

directly on teachers’ individual needs. Experts may share their specialized knowledge as one-on-one

coaches in the classroom, as facilitators of group workshops, or as remote mentors using technology

to communicate with educators. They may include master teachers or coaches based in universities or

professional development organizations.

In one coaching initiative designed to enhance early literacy instruction among Head Start teachers,

educators participated in biweekly sessions with a university-based literacy coach following a two-

day orientation that introduced them to the literacy concepts. Prior to each session (which could be

conducted in person or remotely), coaches and teachers collaboratively chose a specific instructional

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | RESEARCH BRIEF 3

practice on which to focus their time together. Coaches then observed teachers in their classrooms and

provided both supportive and constructive oral and written feedback on their teaching, facilitating the

implementation of desired instructional practices.

For remote coaching, educators shared 15-minute video clips and coaches provided detailed written

feedback, supported by links to video exemplars and other materials available through the program.

The semester-long program included 16 hours of workshops and seven coaching sessions. A two-

year randomized controlled trial found that classrooms led by these teachers demonstrated larger

gains and higher performance on a widely used early childhood classroom quality assessment, and

their students experienced larger gains on a number of early language and literacy skills than did

those in the control group.6

Feedback and Reflection

High-quality professional learning frequently provides built-in time for teachers to think about, receive

input on, and make changes to their practice by facilitating reflection and soliciting feedback. Feedback

may be offered as teachers analyze lesson plans, demonstration lessons, or videos of teacher instruction,

which also provide opportunities for reflection about what might be refined or retained and reinforced.

These activities are frequently undertaken in the context of a coaching session or workshop, but may also

occur among peers.

For example, in a program targeting early childhood educators’ ability to promote children’s language

and literacy development, educators enrolled in a facilitated online course called eCIRCLE. The course

included videos of model lessons, online coursework and knowledge assessments, and opportunities to

plan lessons and practice skills in small groups and in teachers’ own classrooms. The course also offered

interactive message boards that were moderated by expert facilitators. Teachers participated in four

hours of this coursework per month throughout the school year. They received a supplemental curriculum

on preschool language and literacy skills and were encouraged to monitor children’s language and literacy

progress using a common tool. In addition, some educators participated in biweekly on-site mentoring

sessions with the expert facilitators, who observed the teacher’s practice, then facilitated reflective follow-

up and provided positive and constructive feedback. In a randomized controlled study of the program,

researchers found that students of teachers who received expert mentoring and feedback experienced

the greatest gains on a variety of language and literacy outcomes.7

Sustained Duration

Effective professional development provides teachers with adequate time to learn, practice, implement,

and reflect upon new strategies that facilitate changes in their practice. As a result, strong PD initiatives

typically engage teachers in learning over weeks, months, or even academic years, rather than in short,

one-off workshops.8

For example, the Transformative Professional Development program is a two-year PD model to enhance

science instruction for Spanish-speaking elementary school students. The program begins with a

two-week summer workshop that includes graduate-level coursework on teaching elementary science.

Teachers’ learning from this intensive workshop is reinforced through occasional release days and

monthly grade-level workshops with professional learning communities. These additional sessions

support teachers in deepening their learning and provided space for ongoing support in implementing

the new curriculum.

This model not only offers teachers the opportunity to return repeatedly to the PD material over the

course of a semester, but also to apply their learning within the context of their classroom between

workshops. This cycle is repeated in the second year, with an additional summer workshop and

L EARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | RESEARCH BRIEF 4

continued release days. In a comparison group study, students whose teachers participated in the

program demonstrated significantly larger improvements in science achievement over time than

students whose teachers experienced business-as-usual PD.9 By promoting learning over time, both

within and between sessions, PD that is sustained may lead to many more hours of learning than is

indicated by seat time alone.

Putting It All Together

Our research shows that effective professional learning incorporates most or all of these elements.

Well-designed professional learning communities, such as those instituted by the National Writing

Project, can integrate these elements to support teacher learning resulting in student learning gains. This

collaborative and job-embedded professional development, described in additional detail in the box that

follows, can enable widespread improvement within and beyond the school level.

National Writing Project: Learning From Professional Communities

Beyond the School

The National Writing Project (NWP), which began as the Bay Area Writing Project, started in 1973 as a

partnership between the University of California at Berkeley and local school districts. It has grown to over

185 sites in all 50 states, the District of Columbia, Puerto Rico, and the U.S. Virgin Islands. At the heart of

the model are local school-university partnerships, each of which operates as an autonomous site to support

context-specific strengths and meet context-specific challenges.

Despite the autonomy of the local sites, there are common design features

and core principles that guide each site and are aligned with all of the In the process of making their

elements identified in our research. The national network focuses on work public and critiquing

supporting the success of each local site. NWP local sites first focus on

others, teachers learn how

creating community among a small group of teachers during a five-week

summer institute in which teachers engage in writing, share their work, to make implicit rules and

and critique their peers. In the process of making their work public expectations explicit, and

and critiquing others, teachers learn how to make implicit rules and how to give and receive

expectations explicit, and how to give and receive constructive feedback constructive feedback as

as students. These summer institutes are held at each site and run students.

by “teacher consultants”—NWP veteran teachers who are trained and

supported by the national network.

The summer institutes, which are designed to promote risk-taking and collaboration, provide a foundation for

ongoing learning for teachers once they leave. These ongoing professional learning programs are collaboratively

designed by schools and universities and led by teacher consultants. In addition, NWP provides a wide variety

of ways to promote active, collaborative learning within and across sites; newsletters, annual conferences,

and opportunities to lead workshops are catalysts for the continuous engagement of teachers, creating the

intersection of professional learning communities within the school and across the profession.10

A recent random assignment study of the College-Ready Writers Program (CRWP), a National Writing Project

program that focuses specifically on the argument writing of students in grades 7 through 10, demonstrated

its promise for supporting student learning. SRI conducted the study of CRWP in 22 high-poverty rural districts

across 10 states, which were compared to a control group of 22 additional high-poverty rural districts. The

CRWP components included: PD of at least 90 hours over two years with supports that included demonstration

lessons, coaching, codesigning learning tasks, co-planning, curricular resources including lesson units for

argument writing, and formative assessment tools to help teachers focus on student learning. In contrast, the

control group engaged in “business as usual” professional development.

CRWP was found to have a positive, statistically significant impact on three of four attributes of student writing:

content, structure, and stance. The remaining attribute, writing conventions, was marginally significant. Authors

of the study note, “… this study of teacher professional development is one of the largest and most rigorous to

find evidence of an impact on student academic outcomes,” indicating the power of high-quality PD to affect

student achievement improvements at scale.11

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | RESEARCH BRIEF 5

Creating Conditions for Effective Professional Development

The quality of a PD initiative’s implementation

has implications for its overall effectiveness in Even the best-designed

enhancing teacher practice and improving student

professional development may fail

learning. Researchers have found that willing

teachers are sometimes unable to implement to produce desired outcomes if it

professional development practices due to is poorly implemented.

obstacles that are beyond their control.12 Even

the best-designed professional development may

fail to produce desired outcomes if it is poorly

implemented due to barriers such as:

• inadequate resources, including necessary curriculum materials;

• lack of a shared vision about what high-quality instruction entails;

• lack of time for implementing new instructional approaches during the school day or year;

• failure to align state and local policies toward a coherent set of instructional practices;

• dysfunctional school cultures; and

• inability to track and assess the quality of professional development.13

Implementing professional development well also requires responsiveness to the specific needs of

teachers and learners, and to the school and district contexts in which teaching and learning will take

place. These types of common obstacles to professional development should be anticipated and planned

for during both the design and implementation phases of professional development.

Implications for Policy and Practice

Policy can help support and incentivize the kind of evidence-based PD described here. For example:

1. Policymakers could adopt standards for professional development to guide the design,

evaluation, and funding of professional learning provided to educators. These standards might

reflect the features of effective professional learning outlined in this report, as well as standards

for implementation.

2. Policymakers and administrators could evaluate and redesign the use of time and school

schedules to increase opportunities for professional learning and collaboration, including

participation in professional learning communities, peer coaching and observations across

classrooms, and collaborative planning.

3. States, districts, and schools could regularly conduct needs assessments using data from staff

surveys to identify areas of professional learning most needed and desired by educators. Data

from these sources can help ensure that professional learning is not disconnected from practice

and supports the areas of knowledge and skills educators want to develop.

4. State and district administrators could identify and develop expert teachers as mentors and

coaches to support learning in their particular area(s) of expertise for other educators.

5. States and districts can integrate professional learning into their Every Student Succeeds Act

(ESSA) school improvement initiatives, such as efforts to implement new learning standards, use

student data to inform instruction, improve student literacy, increase student access to advanced

coursework, and create a positive and inclusive learning environment.

L EARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | RESEARCH BRIEF 6

6. States and districts can provide technology-facilitated opportunities for professional learning

and coaching, using funding available under Titles II and IV of ESSA to address the needs of rural

communities and provide opportunities for intradistrict and intraschool collaboration.

7. Policymakers can provide flexible funding and continuing education units for learning

opportunities that include sustained engagement in collaboration, mentoring, and coaching, as

well as institutes, workshops, and seminars.

In the end, well-designed and implemented PD should be considered an essential component of a

comprehensive system of teaching and learning that supports students to develop the knowledge,

skills, and competencies they need to thrive in the 21st century. To ensure a coherent system that

supports teachers across the entire professional continuum, professional learning should link to their

experiences in preparation and induction, as well as to teaching standards and evaluation. It should

also bridge to leadership opportunities to ensure a comprehensive system focused on the growth and

development of teachers.

Endnotes

1. Roth, K. J., Garnier, H. E., Chen, C., Lemmens, M., Schwille, K., & Wickler, N. I. Z. (2011). Video-based lesson analysis: Effec-

tive science PD for teacher and student learning. Journal on Research in Science Teaching, 48(2), 117–148.

2. Taylor, J. A., Roth, K., Wilson, C. D., Stuhlsatz, M. A., & Tipton, E. (2017). The effect of an analysis-of-practice, video case-

based, teacher professional development program on elementary students’ science achievement. Journal of Research on

Educational Effectiveness, 10(2), 241–271.

3. Greenleaf, C. L., Hanson, T. L., Rosen, R., Boscardin, D. K., Herman, J., Schneider, S. A., Madden, S., & Jones, B. (2011). Inte-

grating literacy and science in biology: Teaching and learning impacts of reading apprenticeship professional development.

American Educational Research Journal, 48(3), 647–717.

4. Lara-Alecio, R., Tong, F., Irby, B. J., Guerrero, C., Huerta, M., & Fan, Y. (2012). The effect of an instructional intervention on

middle school English learners’ science and English reading achievement. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 49(8),

987–1011.

5. Heller, J. I., Daehler, K. R., Wong, N., Shinohara, M., & Miratrix, L. W. (2012). Differential effects of three professional de-

velopment models on teacher knowledge and student achievement in elementary science. Journal of Research in Science

Teaching, 49(3), 333–362.

6. Powell, D. R., Diamond, K. E., Burchinal, M. R., & Koehler, M. J. (2010). Effects of an early literacy professional development

intervention on Head Start teachers and children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(2), 299–312.

7. Landry, S. H., Anthony, J. L., Swank, P. R., & Monseque-Bailey, P. (2009). Effectiveness of comprehensive professional devel-

opment for teachers of at-risk preschoolers. Journal of Educational Psychology, 101(2), 448–465.

8. Darling-Hammond, L., Wei, R. C., Andree, A., Richardson, N., & Orphanos, S. (2009). Professional learning in the learning pro-

fession. Washington, DC: National Staff Development Council; Desimone, L. M. (2009). Improving impact studies of teachers’

professional development: Toward better conceptualizations and measures. Educational researcher, 38(3), 181–199.

9. Johnson, C. C. & Fargo, J. D. (2014). A study of the impact of transformative professional development on Hispanic student

performance on state mandated assessments of science in elementary school. Journal of Elementary Science Teacher

Education, 25(7), 845–859.

10. Lieberman, A. & Wood, D. (2002). From network learning to classroom teaching. Journal of Educational Change, 3, 315–337;

McDonald, J. P., Buchanan, J., & Sterling, R. (2004). The National Writing Project: Scaling up and scaling down. Expanding the

reach of education reforms: Perspectives from leaders in the scale-up of educational interventions, 81–106.

11. Gallagher, H. A., Woodworth, K. R., & Arshan, N. L. (2017). Impact of the National Writing Project’s College-Ready Writers

Program in high-need rural districts. Journal of Research on Educational Effectiveness, online, 37.

12. Buczynski, S. & Hansen, C. B. (2010). Impact of professional development on teacher practice: Uncovering connections.

Teaching and Teacher Education, 26(3), 606.

13. Tooley, M. & Connally, K. (2016). No panacea: Diagnosing what ails teacher professional development before reaching for

remedies. Washington, DC: New America.

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | RESEARCH BRIEF 7

About the Learning Policy Institute

The Learning Policy Institute conducts and communicates independent, high-quality

research to improve education policy and practice. Working with policymakers, researchers,

educators, community groups, and others, the Institute seeks to advance evidence-

based policies that support empowering and equitable learning for each and every child.

Nonprofit and nonpartisan, the Institute connects policymakers and stakeholders at the

local, state, and federal levels with the evidence, ideas, and actions needed to strengthen

the education system from preschool through college and career readiness.

1530 Page Mill Road, Suite 200 Palo Alto, CA 94304 (p) 650.332.9797

1301 Connecticut Avenue NW, Suite 500 Washington, DC 20036 (p) 202.830.0079

@LPI_Learning | learningpolicyinstitute.org

LEARNING POLICY INSTITUTE | RESEARCH BRIEF 8

You might also like

- What Great Principals Do Differently Book Review100% (1)What Great Principals Do Differently Book Review4 pages

- Daleen Smith Special Education Teacher ResumeNo ratings yetDaleen Smith Special Education Teacher Resume3 pages

- Effective Teacher Professional Development REPORTNo ratings yetEffective Teacher Professional Development REPORT76 pages

- Effects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsFrom EverandEffects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsNo ratings yet

- Is It Working in Your Middle School?: A Personalized System to Monitor Progress of InitiativesFrom EverandIs It Working in Your Middle School?: A Personalized System to Monitor Progress of InitiativesNo ratings yet

- Classroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 ClassroomsFrom EverandClassroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 ClassroomsNo ratings yet

- Principals Set Goals For New School Year and PD TipsNo ratings yetPrincipals Set Goals For New School Year and PD Tips9 pages

- Reading Enrichment Unit: Identify Desired Results (Stage 1) Content StandardsNo ratings yetReading Enrichment Unit: Identify Desired Results (Stage 1) Content Standards2 pages

- Call Me American: Finding Your Place in The WorldNo ratings yetCall Me American: Finding Your Place in The World2 pages

- Engaging All Students - Strategies To Promote Meaningful Learning100% (1)Engaging All Students - Strategies To Promote Meaningful Learning39 pages

- Professional Dispositions Statement Assessment100% (2)Professional Dispositions Statement Assessment5 pages

- The Real Cost of The No Child Left Behind Act Annie GbafordNo ratings yetThe Real Cost of The No Child Left Behind Act Annie Gbaford6 pages

- Four Pillars of Parental Engagement: Empowering schools to connect better with parents and pupilsFrom EverandFour Pillars of Parental Engagement: Empowering schools to connect better with parents and pupils5/5 (1)

- McREL WhitePaper Student Learning That-Works 2018 Web100% (1)McREL WhitePaper Student Learning That-Works 2018 Web16 pages

- Maryland Teacher Professional Development Planning Guide: Updated November 2008No ratings yetMaryland Teacher Professional Development Planning Guide: Updated November 200826 pages

- Achenjangteachingphilosophy: Unorthodox Medicinal TherapiesNo ratings yetAchenjangteachingphilosophy: Unorthodox Medicinal Therapies2 pages

- On Teacher Collaboration - The Art of StrengtheningNo ratings yetOn Teacher Collaboration - The Art of Strengthening16 pages

- Epstein's Six Types of Parent InvolvementNo ratings yetEpstein's Six Types of Parent Involvement1 page

- 5 Ways To Make Teacher Professional Development EffectiveNo ratings yet5 Ways To Make Teacher Professional Development Effective15 pages

- Integrating Differentiated Instruction & Understanding by Design: Connecting Content and Kids, 1st EditionNo ratings yetIntegrating Differentiated Instruction & Understanding by Design: Connecting Content and Kids, 1st Edition10 pages

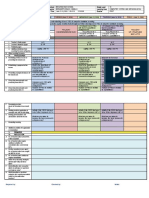

- Practicum Plan and Campus-Supervised Log1No ratings yetPracticum Plan and Campus-Supervised Log115 pages

- EDUC5010 Week 3 Written Assignment Unit 3No ratings yetEDUC5010 Week 3 Written Assignment Unit 37 pages

- Student Engagement Strategies For The Classroom100% (1)Student Engagement Strategies For The Classroom8 pages

- Seager B Sped875 m2 Mentor Teacher CollaborationNo ratings yetSeager B Sped875 m2 Mentor Teacher Collaboration4 pages

- Atlanta Public Schools - Equity Audit Report FinalNo ratings yetAtlanta Public Schools - Equity Audit Report Final97 pages

- Discussion Patterns in Development Developmental SequenceNo ratings yetDiscussion Patterns in Development Developmental Sequence20 pages

- Discussion Patterns in Development Developmental SequenceNo ratings yetDiscussion Patterns in Development Developmental Sequence8 pages

- 2016 Xu & Brown TALiP-TATE Author VersionNo ratings yet2016 Xu & Brown TALiP-TATE Author Version39 pages

- Lesson Plan in Tle 7 and 8 - Ia Third Grading (Automotive Servicing)100% (2)Lesson Plan in Tle 7 and 8 - Ia Third Grading (Automotive Servicing)2 pages

- Magsaysay Ave. Karangalan Village, Manggahan Pasig CityNo ratings yetMagsaysay Ave. Karangalan Village, Manggahan Pasig City5 pages

- Tactical Approach To Games For UnderstandingNo ratings yetTactical Approach To Games For Understanding15 pages

- Pengembangan Model Pembelajaran Diskusi Dan PersonNo ratings yetPengembangan Model Pembelajaran Diskusi Dan Person6 pages

- m06 Beyond The Basic Prductivity Tools Lesson Idea TemplateNo ratings yetm06 Beyond The Basic Prductivity Tools Lesson Idea Template2 pages

- We Care For One Another in Our Family.: Kindergarten Lesson PlanNo ratings yetWe Care For One Another in Our Family.: Kindergarten Lesson Plan10 pages

- Assessment in Learning 2 Prof. Ed 7 Activity 3No ratings yetAssessment in Learning 2 Prof. Ed 7 Activity 35 pages

- Pinamanculan National High School: Weekly Home Learning Plan Quarter 2 Week - 2 Grade 8 SY: 2020-2021No ratings yetPinamanculan National High School: Weekly Home Learning Plan Quarter 2 Week - 2 Grade 8 SY: 2020-20212 pages

- Effects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School EducatorsFrom EverandEffects of an Inclusion Professional Development Model on Inclusion Knowledge and Perceptions of Regular Middle School Educators

- Academic Excellence Through Equity: When Money TalksFrom EverandAcademic Excellence Through Equity: When Money Talks

- Improving On-Task Behaviors in the ClassroomsFrom EverandImproving On-Task Behaviors in the Classrooms

- Is It Working in Your Middle School?: A Personalized System to Monitor Progress of InitiativesFrom EverandIs It Working in Your Middle School?: A Personalized System to Monitor Progress of Initiatives

- Professional Development and the Mathematics EducatorFrom EverandProfessional Development and the Mathematics Educator

- Classroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 ClassroomsFrom EverandClassroom-Ready Resources for Student-Centered Learning: Basic Teaching Strategies for Fostering Student Ownership, Agency, and Engagement in K–6 Classrooms

- Principals Set Goals For New School Year and PD TipsPrincipals Set Goals For New School Year and PD Tips

- Reading Enrichment Unit: Identify Desired Results (Stage 1) Content StandardsReading Enrichment Unit: Identify Desired Results (Stage 1) Content Standards

- Engaging All Students - Strategies To Promote Meaningful LearningEngaging All Students - Strategies To Promote Meaningful Learning

- The Real Cost of The No Child Left Behind Act Annie GbafordThe Real Cost of The No Child Left Behind Act Annie Gbaford

- Four Pillars of Parental Engagement: Empowering schools to connect better with parents and pupilsFrom EverandFour Pillars of Parental Engagement: Empowering schools to connect better with parents and pupils

- McREL WhitePaper Student Learning That-Works 2018 WebMcREL WhitePaper Student Learning That-Works 2018 Web

- Maryland Teacher Professional Development Planning Guide: Updated November 2008Maryland Teacher Professional Development Planning Guide: Updated November 2008

- Achenjangteachingphilosophy: Unorthodox Medicinal TherapiesAchenjangteachingphilosophy: Unorthodox Medicinal Therapies

- On Teacher Collaboration - The Art of StrengtheningOn Teacher Collaboration - The Art of Strengthening

- 5 Ways To Make Teacher Professional Development Effective5 Ways To Make Teacher Professional Development Effective

- Integrating Differentiated Instruction & Understanding by Design: Connecting Content and Kids, 1st EditionIntegrating Differentiated Instruction & Understanding by Design: Connecting Content and Kids, 1st Edition

- Atlanta Public Schools - Equity Audit Report FinalAtlanta Public Schools - Equity Audit Report Final

- Discussion Patterns in Development Developmental SequenceDiscussion Patterns in Development Developmental Sequence

- Discussion Patterns in Development Developmental SequenceDiscussion Patterns in Development Developmental Sequence

- Lesson Plan in Tle 7 and 8 - Ia Third Grading (Automotive Servicing)Lesson Plan in Tle 7 and 8 - Ia Third Grading (Automotive Servicing)

- Magsaysay Ave. Karangalan Village, Manggahan Pasig CityMagsaysay Ave. Karangalan Village, Manggahan Pasig City

- Pengembangan Model Pembelajaran Diskusi Dan PersonPengembangan Model Pembelajaran Diskusi Dan Person

- m06 Beyond The Basic Prductivity Tools Lesson Idea Templatem06 Beyond The Basic Prductivity Tools Lesson Idea Template

- We Care For One Another in Our Family.: Kindergarten Lesson PlanWe Care For One Another in Our Family.: Kindergarten Lesson Plan

- Pinamanculan National High School: Weekly Home Learning Plan Quarter 2 Week - 2 Grade 8 SY: 2020-2021Pinamanculan National High School: Weekly Home Learning Plan Quarter 2 Week - 2 Grade 8 SY: 2020-2021