Dimensions of Organizational Commitment

Dimensions of Organizational Commitment

Uploaded by

Pedro HerreraCopyright:

Available Formats

Dimensions of Organizational Commitment

Dimensions of Organizational Commitment

Uploaded by

Pedro HerreraCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Dimensions of Organizational Commitment

Dimensions of Organizational Commitment

Uploaded by

Pedro HerreraCopyright:

Available Formats

Dimensions of Organizational Commitment

Author(s): Helen P. Gouldner

Source: Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol. 4, No. 4 (Mar., 1960), pp. 468-490

Published by: Sage Publications, Inc. on behalf of the Johnson Graduate School of Management,

Cornell University

Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2390769 .

Accessed: 14/06/2014 18:18

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at .

http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp

.

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of

content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms

of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Sage Publications, Inc. and Johnson Graduate School of Management, Cornell University are collaborating

with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Administrative Science Quarterly.

http://www.jstor.org

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

HelenP. Gouldner

Dimensions of Organizational

Commitment

The author reports on a factor analytic study which distinguishes

different dimensions of organizational commitment among the mem-

bers of a voluntary association. Among the forms of organizational

commitment studied were: cosmopolitan integration-the degree to

which the individual is active in and feels himself a part of the varying

levels of a particular organization, and is active, as well, in other

organizations; and organizational introjection-the degree to which

the individual's "ideal" self-image includes a number of organizational-

ly approved qualities and values. In addition to the factors of organi-

zational commitment, two other factors were identified as reflecting

commitment to two specific values of the organization. The emergence

of these lends support to a basic hypothesis of the study, namely, that

commitment to the specific values of an organization is distinct from

commitment to the organization as a whole.1

Helen P. Gouldner is associate professor and chairman, Department

of Sociology, Lindenwood College.

IT has of course long been obvious that the members of an associ-

ation differ greatly in the degree of their commitment to the

'The author acknowledges with great pleasure the support of the Social Science

Research Council, many helpful suggestions from Leonard Broom, Richard T.

Morris, and Ralph H. Turner, interviewing assistance from Mary Bob Chesler,

assistance in computations from Kern Dickman, and aid in all phases of the research

from Alvin W. Gouldner.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT 469

organization. At both poles variations in the degree of commit-

ment have been problems. Attention has been directed, on the

one hand, to the fanatical zeal of the political and religious secta-

rians and, on the other, to the apathy of the members of some

unions or fraternal and civic organizations.2 These extremes in a

democratic culture that regards them both with suspicion have

been of concern both to social scientists and citizens. Partly because

of this interest in the degree of organizational commitment, how-

ever, less attention has been paid to the fact that members differ

also in the form of their commitment. It is the main hypothesis of

this paper that organizational commitment is not a homogeneous

and unidimensional variable but is, instead, a multidimensional

phenomenon.

Along these lines, Herbert Simon was one of the first to suggest

that commitment to an organization as a whole is distinguishable

from a commitment to its specific values, policies, or goals.3Recent-

ly, James Coleman and others have made a similar distinction

between those who are "idea-oriented," forming attachments on

the basis of values and ideals, and those who are "group-oriented,"

forming attachments through group loyalties.4 This distinction

between over-all commitment and commitment to particular goals

is important for organizational analysis, because it suggests that

those who are committed only to the goals of an organization may

resign or withdraw should these be changed.

The objective of our research, then, was to identify some of the

components or dimensions of organizational commitments and to

begin to explore the relations among them. It seems obvious that

the problem of organizational commitment involves an issue of

2For studies of extreme differences in degree of commitment compare Philip

Selznick, The Organization Weapon: A Study of Bolshevik Strategy and Tactics

(New York, 1952), pp. 25-29, and Scott A. Greer, "The Participation of Ethnic

Minorities in the Labor Unions of Los Angeles County" (Ph.D. dissertation, Univer-

sity of California, Los Angeles, 1952). See also Arnold M. Rose, Union Solidarity

(Minneapolis, 1952).

"H. A. Simon, D. W. Smithburg, and V. A. Thompson, Public Administration

(New York, 1950), pp. 94-100.

4James S. Coleman, Multidimensional Scale Analysis, American Journal of Sociol-

ogy, 63 (1957), 255.

5As the term commitment is used here, it refers to those kinds of constraints which

are generated by the actor's own motivations, orientations, and behaviors.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

470 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

basic sociological interest, concerned as it is with the diverse ways

in which individuals attach themselves to groups. In one way or

another many investigations, including research in group cohesive-

ness, integration, influence, and morale either are implicitly

premised on, or explicitly postulate assumptions about organiza-

tional commitment and use this concept as a dependent, indepen-

dent, or intervening variable. It seems likely, therefore, that the

identification of distinct forms of organizational commitment will

increase our knowledge about some of the basic group processes.

For example, differences in the kind (as well as the amount) of

commitment an individual has to a group are likely to affect the

degree and kind of influence that the group can exert upon him.

Similarly, the identification of different forms of organizational

commitment should also contribute to our understanding of such

group attributes as cohesion. The studies of Festinger, Schachter,

Back, Emerson, and others" assume that group cohesion is a

unidimensional variable. However, if the individual's commitment

to the group is one force generating group cohesion, and if there

are several distinctive forms of commitment to a group, it is likely

that there are several distinguishable forms of group cohesion.

SETTING OF THE STUDY

The study reported here was carried out among members of the

Los Angeles League of Women Voters. The League is a large and

nationally organized women's voluntary association devoted to

''promoting political responsibility through informed and active

participation of citizens in government." The organization of the

League is modeled after the government, with national, state, and

local groups. League activities include providing nonpartisan,

factual information to voters on registration, voting procedures,

candidates, public officials, and issues. The members study and

"For a review of several studies in this area see L. Festinger, Informal Social Com-

munication, Psychological Review, 57 (1950), 271-282. See also Richard M. Emerson,

Deviation and Rejection: An Experimental Replication, American Sociological

Review, 19(1954), 688-693. For research and discussions on the problem of group

cohesiveness see K. W. Back, Influence through Social Communication, Journal of

Abnormal and Social Psychology, 46 (1951), 9-32; Dorwin Cartwright and Alvin

Zander, eds., Group Dynamics (Evanston, 1953), especially pp. 87-88; N. Gross and

W. E. Martin, On Group Cohesiveness, and Stanley Schachter's Comment, American

Journal of Sociology, 57 (1952), 546-562.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT 471

sometimes take action on various issues and problems in national,

state, and local government.

After several months of field work, which included observation

at meetings, interviews, and a study of League documents, a work-

ing sample was selected by taking every nth name from an alpha-

betical list of members provided by League leaders. From this

working sample, sixty interviews were completed and these con-

stitute the main body of data for the following analysis. The data

also include responses to mailed questionnaires, which had been

filled out and were collected at the time of the interview. Inter-

views with each member ranged from about two to four hours.

The sample is largely composed of highly educated, middle-to-

upper-class married women with two or three children of school

age.

THE HYPOTHESIZED DIMENSIONS

In constructing commitment measures the focus was not only

on items which would test the degree of commitment to the

organization but also on items which might reveal different forms

or dimensions of this commitment. A major distinction was made

between commitment to the organization as a whole and commit-

ment to specific values of the organization.7 Sample items on each

of these major dimensions are listed below.

Commitment to the Total Organization

One set of items sought to reveal "integration," that is, the

degree to which the individual feels a part of and has a sense of

belonging to the varying levels of the organization. These items

included the following:

Membersof the League differ in their sense of closeness to different

partsof the organization.Do you feel a real part of... (1) Your branch

group? (2) the city League as a whole? (3) the state League? (4) the

national League?

Categories for each of these items ranged on a five-point scale

from "not at all" to "very much."

A further item was developed to measure "introjection." This

item is limited in the present study to an indication of the degree

7Several other commitment variables, including involvement with organizational

subgroups have not been included in the present analysis. See Simon et al., op. cit.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

472 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

to which the individual's ideal self-image includes a variety of

League-approved qualities and values. More specifically, it is a

reflection of the respondent's desire to mold her personality, char-

acter, or behavior in terms of general League ideals, values, and

norms. It is, in one part, a measure of the degree to which the

organization is an "identification" reference group.8 The item was

stated as follows:

Try for a minute to step outside yourself, to... look at yourself....

What kind of a League memberwould (respondent'sname) like to be?

What do you think you would say about yourself?

Responses were coded on a three-point scale ranging from "low

introjection," little or no indication of desire to mold personal

character to League values and no mention of specific desired

changes, to "high introjection," indication of such desire and

mention of two or more specific desired changes in self.

In addition to the items specifically designed to tap integration

and introjection, a number of other items related to organizational

commitment were developed. These included various measures of

activity and participation, highest office held, degree of enthusiasm

about the League, degree of confidence that the League would

achieve its over-all goals, preference for the League over other

organizations, and readiness to give up time spent in other organi-

zations or in social life outside the family to maintain present

level of activity in the League.

Commitment to Specific Organizational Values

On the hypothesis that commitment to a specific organizational

value is often independent of commitment to the organization as

a whole, and, further, that commitment to one organizational value

is sometimes independent of commitment to another, three values

specific to the League were singled out for special study. These

were: (1) cross-sectional membership-the desirability of getting

members from different income brackets, different political phi-

losophies, different levels of education, and so forth; (2) political

party responsibility-the desirability of including individuals con-

8Ralph H. Turner has isolated several types of reference groups including the

identification group which is defined as the source of the individual's major per-

spectives and values. See his Role-Taking, Role Standpoint, and Reference-Group

Behavior, American Journal of Sociology, 61 (1956), &27-328.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT 473

sistently supporting one political party; (3) soliciting funds from

the community-the desirability of going to the community for

financial aid to supplement dues and member contributions.9 The

major interest here is not these particular values (indeed, others

might have been chosen), but rather whether commitment to any

specific organizational value is independent of other forms of

organizational involvement.

These values were presented to the respondents in the form of

an idea (or principle or policy) that was preferable or desirable for

the organization, which differs from asking them for their personal

preference. On the whole, however, the data suggest a relationship

between organization preference and personal preference (i.e., if

a respondent preferred the value for the organization, she also

often preferred it for herself). Nevertheless, a distinction between

organizational and personal preference still proved useful. With-

out this distinction, for example, many of the respondents would

have indicated a preference for fund-raising events over soliciting

funds, had we asked them only for a personal choice, even though

in principle they did approve of the League soliciting funds as an

organization. As one woman commented, "It's all right as long as

I don't have to do it."

The items measuring value commitment were also designed to

test the degree of private commitment to the value concerned, as

opposed to getting at a more limited public commitment.10 (An

individual who is privately committed to a value will tend to main-

tain a consistent position in favor of this value in varying situations

and groups-even where the majority of a group is opposed to the

value-whereas an individual who is only publicly committed may

change her opinion according to the position of the group she

happens to be in.)"

The value commitment score was derived as follows: After some

discussion, the respondent was asked to sum up the position she

9Each of these are justified preferences. For example, soliciting funds from the

community is preferred over fund-raising events (bazaars, teas, theater parties)

"because statistics have shown that returns are greater per unit of time spent" and

so forth. This conforms to the definition of values currently in use.

:0A brief review of the literature on this distinction is found in Harold H. Kelley

and Edmund H. Volkart, The Resistance to Change of Group-Anchored Attitudes,

American Sociological Review, 17 (1952), 455-456.

:1Cf. Turner's discussion of the internalization of norms, op. cit., p. 3,26.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

474 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

had taken on the value in actual League discussions (or would

take if the value were being discussed) on a six-point scale ranging

from "strongly opposed" to "very strongly in favor." A series of

questions probing for private doubts followed and the respondent

was then asked to place herself in a hypothetical League meeting

where the value was being discussed. In each case the group in

this hypothetical situation was opposed to the position the

respondent had initially taken on the value. Each respondent was

then asked to choose again from the same set of categories that

which would best sum up their private feelings in this situation.

The commitment score was computed by comparing the answers

in the first and second ratings, the resulting scale ranging from

"opposed and did not change positions" to "very strongly in favor

and did not change positions." This set of questions was repeated

for each of the three values, giving three separate value

commitment scores.12

Other items thought to be related to value commitment were

developed. These included questions for each value on personal

salience, private doubts, number of qualifications, discussion of

value with other League members, use of standard League argu-

ments in support of value position, and objectivity in discussing

the value. "Objectivity" (the weighing of pros and cons or some

posture of "getting the facts first") is a highly pervasive League

value, which affects the ability to become committed to any

specific value or policy.

THE FACTOR ANALYSIS

After the data were collected and coded, factor analysis was used

as a tool for refining and developing the hypothesized dimensions

and as a test of their independence.13 In all, forty-one items were

'"There is some evidence to suggest that, with all the obvious drawbacks of this

instrument, it did tap a greater degree of commitment than would have been the

case had we used a single question and had not forced the respondent to attend

to alternative reference groups. For one thing, many respondents did change their

position. Those with many doubts and qualifications were likely to score lower the

second time. There is evidence, too, that these portions of the interview were some-

what anxiety provoking, which might be expected in cases where there is disparity

between "private" and "public" opinion.

"3Factoranalysis is a method for identifying a multiplicity of items which cluster

together. It is also useful as a scanning device enabling the researcher to detect

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT 475

intercorrelated using Pearson's product-moment correlation. Seven

factors were extracted by Thurstone's centroid method and were

rotated to both orthogonal and oblique simple structure, using

the "Quartimax" and "Oblimax" methods of rotation respective-

ly.14 (Rather than being graphic trial-and-errormethods, these are

analytical methods that have been adapted for use on electronic

computers.) In order to obtain the clearest solution possible, the

oblique analysis was carried several steps further than is ordinarily

done, to secure "primary"factors rather than stopping the analysis

with the "reference vectors."'15The results indicated five inter-

pretable orthogonal factors and six interpretable oblique factors

(see Appendix, Tables 1 and 2).

The factors are presented and interpreted below. (Only those

items with loadings above .30 are listed.) Inasmuch as many of the

factors include both negative and positive loadings, the response

category corresponding to the direction of the loading of any par-

ticular item is indicated with two asterisks to facilitate interpreta-

tion. Further, while it is often possible to interpret factors at either

end of a positive-negative continuum, interpretation is limited

here to only one "side" of the factor, usually the "positive" side.

Factor 1 reflects the degree of integration into the varying levels

and activities of the organization, particularly the middle organi-

zational levels. With a loading of .90, item 30 ("Do you feel a real

part of the city League as a whole?") is a good measure of this

factor. A sense of closeness, or feeling of belonging to other levels

dimensions other than those he had planned to include in a given domain or sample

of items. Furthermore, by indicating the items most highly loaded with the under-

lying dimension, it may provide a more parsimonious measure of that dimension,

allowing fewer items to be used as a measure of the dimension in later research.

'4Orthogonal dimensions are independent of and only randomly related to each

other; oblique dimensions, on the other hand, may or may not be correlated. In an

oblique rotation there is no attempt to maintain strict independence among the

factors.

The seven centroid factors represented 54 per cent of the common variance in

the total set of items. For a description of the "Quartimax" and "Oblimax" methods

of rotation see J. 0. Neuhaus and C. F. Wrigley, The Quartimax Method: An

Analytic Approach to Orthogonal Simple Structure, British Journal of Statistical

Psychology, 7 (1954), 81-91, and D. R. Saunders and C. Pinska, Analytic Rotation to

Simple Structure: Extension to an Oblique Solution, Research Bulletin, Princeton

Educational Testing Service, 1954.

'rSee Raymond B. Cattell, Factor Analysis (New York, 1952), pp. 219-2-23, 426.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

476 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

Factor1 (Orthogonal):Integration

Load- Item

ings No.

.90 30 Feel a real part of city League: notat all. . .verymuch**

.82 43 Extent of activity: inactive.. .extremely active**

.77 31 Feel a real part of state League: notat all. . .verymuch**

.77 17 Attendance, League Day: never.. .everymeeting**

.74 29 Feel a real part of branch group: not at all. . .verymuch**

.72 32 Feel a real part of national League: notat all. . .verymuch**

.72 16 Attendance, branch meetings: never.. .everymeeting**

.67 41 Offices or committees: no officesor committee work. . .city board

member* *

.66 26 Enthusiasm about membership: a little. . .extremely**

.62 47 Introjection: low. . .high**

.57 52 Discussed or heard discussed cross-sectional membership: no,

yes* *

.54 20 Readiness to give up time in other organizations: wouldnot

give up. . .wouldreadilygive up**

.52 C30 Awareness of cross-sectional membership as League value:

no awareness.. .stronglyaware**

.46 27 Would rather belong to League than other women's organiza-

tions: no,yes **

.41 24 Preference for group discussions over outside speakers: no,

yes* *

.41 76 Commitment score on soliciting funds from the community:

opposed.. .verystronglyinfavor* *

.38 72 Discussed or heard discussed soliciting funds: no,yes**

.37 68 Arguments on soliciting funds: extra-Leaguearguments.. .

standardLeaguearguments**

.34 48 Arguments on cross-sectional membership: extra-League

arguments.. .standardLeaguearguments* *

.33 77 Personal importance, soliciting funds: none. . .a greatdeal**

of the organization-the state League, branch group, and national

League-have somewhat lower, but nonetheless high loadings.

The high loadings of items on attendance at meetings and general

level of activity further support the hypothesis that this dimension

is indicative of integration. This factor describes the "active minor-

ity," those members who often referred to their League activities

as a career or a profession from which they withdrew only, as one

woman put it, "to take a sabbatical leave."

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT 477

The oblique solution has tended to divide this general ortho-

gonal factor into two dimensions. Oblique Factor A suggests what

has been termed "cosmopolitan integration." Oblique Factor B,

on the other hand, reflects "organizational introjection."

The items for Factor A are as follows:

FactorA (Oblique):Cosmopolitan Integration

Load- Item

ings No.

.91 32 Feel a real part of national League: notat all. . .verymuch**

.90 31 Feel a real part of state League: notat all. . .verymuch**

.84 30 Feel a real part of city League: notat all. . .verymuch**

.84 16 Attendance, branch meetings: never.. .everymeeting**

.81 43 Extentof activity:inactive.. .extremely active**

.73 17 Attendance, League Day: never.. .everymeeting**

.67 52 Discussed cross-sectionalmembership: no,yes**

.55 19 No. of other organizations in which respondent holds office:

none. . . threeor-more**

.53 29 Feel a real part of branch group: notat all. . .verymuch**

.52 24 Preference for group discussions over outside speakers: no,

yes* *

.45 27 Would rather belong to League than other women's organiza-

tions:no,yes* *

.46 18 No. of other organizations in which respondent is active:

none. . four ormore**

.44 20 Readiness to give up time in other organizations: would not

give up. . . wouldreadilygive up* *

.42 26 Enthusiasm about membership: a little. . extremely**

As with Factor 1 this oblique factor reflects integration. A

respondent with a high score feels herself to be an integral part of

the organization and is active in it. The factor contains both

cognitive and affective forms of commitment to the organization

as a whole.

In contrast to Factor 1, however, Factor A seems to indicate not

only a sense of integration into but a "cosmopolitan" orientation

toward the organization. While the factor consists of integration

or a sense of closeness to all levels of the organization, integration

with the higher, national and state levels is dominant. The factor

describes a woman who identifies with the League not merely in

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

478 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

terms of its local units but as a national organization or social

movement with society-wide goals."6Even though she prefers the

League, and is both loyal to and active in it, she is also active in

other organizations.

Factor B (Oblique): Introjection

Load- Item

ings No.

.82 47 Introjection: low. . .high**

.58 C30 Awareness of cross-sectional membership as League value:

no awareness. . .strongly aware* *

.56 41 Offices or committees: no officesor committeework. . .city board

member**

.45 26 Enthusiasm about membership: a little. . .extremely**

.45 29 Feel a real part of branch group: a little. . .verymuch**

.39 21 Readiness to give up time spent in social life outside the

family: would not give up. . .would readily give up* *

.38 67 Personal importance, political party responsibility: none. . .

a great deal* *

.33 69 Number of qualifications, soliciting funds from the com-

munity: none. . four or more* *

The highest ranking item on Factor B measures "organizational

introjection'.17 While Factor A, cosmopolitan integration, reflects

the degree to which respondents feel themselves to be a part of the

organization, this introjective dimension, Factor B, consists of the

degree to which the respondents feel the organization to be a part

of themselves. It is an affective and evaluative dimension. An

individual with a high score on this factor judges, guides, and

evaluates her behavior from the standpoint of a variety of League

values and norms.

Factor B also indicates that introjection is related to holding

"'A. W. Gouldner has analyzed the roles of "locals" and "cosmopolitans" in various

organizational settings. One of the specific dimensions he used to define "cosmo-

politans" is the use of an outer reference group orientation, which in this case may

be taken to mean orientation to the League as a national organization, rather than

exclusive orientation to local units, and to other organizations besides the League.

See Cosmopolitans and Locals: Toward an Analysis of Latent Social Roles-I,

Administrative Science Quarterly, 2 (1957), 281-306.

"7Thesixth orthogonal factor is a residual (see Table 1), but is similar to Factor B

in that the introjection item had one of the highest loadings (-.39).

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT 479

office in the organization. This suggests that the more specific the

organizational expectations and the greater the pressure for con-

formity to these expectations (as is true for officeholders),the more

the expectations become introjected.18 Officers act out specific

organizationally approved patterns of behavior, which are rewarded

and become, in turn, part of the self-image. An alternative but not

contradictory hypothesis is that members with a high level of

organizational introjection will more often volunteer or be drafted

for offices and important committees. Here, again, the performance

of specific roles would tend to reinforce organizational introjection.

Let us now examine some of the other factors:

Commitment to a Specific Value: Cross-sectional Membership*

Factor2 FactorC Item

Orthogonal Oblique No.

Rank Load- Load- Rank

ings ings

1. .74 .81 2 56 Commitment score on cross-sectional

membership: opposed.. .strongly in fa-

vor* *

2. .72 .82 1 57 Personal importance, cross-sectional

membership: none. . .a great deal* *

3. -.64 -.76 3 49 No. of qualifications, cross-sectional

membership: none* .*. . four or more

4. -.53 -.69 4 55 Private doubts, cross-sectional member-

ship: not at all* . . .pretty definitely

5. .38 .15 8 47 Introjection: low. . .high**

6. .31 .20 7 48 Arguments on cross-sectional member-

ship: extra-Leaguearguments.. .standard

League arguments**

10. .23 .32 5 C34 Uses objectivity in discussing political

party responsibility: no,yes**

11. -.22 -.31 6 46 Emphasis on friendships in the League

vs. emphasis on educational aims:

friends**. . .educationalaims

*In the presentation of the remaining factors all factor loadings above .30 on either

the oblique or orthogonal solutions are presented for comparison.

:8Cf. Arnold M. Rose, The Adequacy of Women's Expectations for Adult Roles,

Social Forces, 30 (Oct. 1951), 69-77, and James G. March, Group Norms and the

Active Minority, American Sociological Review, 19 (1954), 738.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

480 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

Orthogonal Factor 2 and Oblique Factor C involve a commit-

ment to the specific value or policy of cross-sectional membership

in the League. Respondents with a high score on this factor took a

positive position on the value and did not change their position

under pressure; they placed high personal salience on the value,

gave few qualifications and had few private doubts about their

position. The emergence of this as an orthogonal factor supports

the hypothesis that commitment to the values of an organization

may be independent of commitment to the organization as a whole.

This factor indicates commitment to another specific League

Commitment to a Specific Value: Political Party Responsibility

Factor3 FactorD Item

Orthogonal Oblique No.

Rank Load- Load- Rank

ings ings

1. -.66 -.74 1 65 Private doubts, political party responsi-

bility: not at all** . . .definitely

2. -.62 -.73 3 59 No. of qualifications, political party

responsibility: none*. . .four or more

3. .62 .63 4 67 Personal importance, political party

responsibility: none. . .a great deal**

4. .61 .73 2 66 Commitment score on political party

responsibility: opposed.. .stronglyin fa-

vor* *

5. .40 .40 5 C30 Awareness of cross-sectional member-

ship as League value: none. . strongly

aware* *

6. .37 .40 6 58 Arguments on political party responsi-

bility: extra-Leaguearguments.. .standard

League arguments* *

7. -.36 -.36 8 27 Would rather belong to the League than

other women's organizations: no,* * yes

8. -.35 -.40 7 28 Confidence in ability of the League to

achieve its goals: a little **. . .extremely

9. -.30 -.35 9 20 Readiness to give up time in other or-

ganizations: would not give up* *. .

wouldreadilygive up

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT 481

value, responsibility to a political party. It loads heavily questions

on private doubts, number of qualifications, personal importance,

and the commitment score on political party responsibility.'9 The

emergence of this as an orthogonal factor again supports the

hypothesis that commitment to an organizational value is inde-

pendent of commitment to the total organization, as well as of

other organizational values.

Exposure to Organizational Culture

Factor4 FactorE Item

Orthogonal Oblique No.

RankLoad- Load-Rank

ings ings

1. .63 .68 2 62 Discussed or heard discussedpolitical

party responsibility:no,yes**

2. .62 .70 1 C25 Uses objectivity in discussing cross-

sectionalmembership:no,yes**

3. .61 .61 3 58 Type of argumentson political party

responsibility:extra-Leaguearguments.

. .

standardLeaguearguments* *

4. .52 .47 6 68 Type of argumentson solicitingfunds

from the community:extra-League argu-

ments. .. standard Leaguearguments**

5. .51 .57 5 72 Discussedor heard discussedsoliciting

fundsfrom the community:no,yes**

6. .51 .57 4 48 Type of arguments on cross-sectional

membership:extra-League . .

arguments.

standardLeaguearguments* *

7. .38 .32 7 52 Discussedor heard discussedcross-sec-

tional membership:no,yes* *

This factor involves degree of exposure to League "culture,"

rather than a particular dimension of commitment. To the extent

that the term "socialization" refers to the use of skills and group

:'Other items on this factor suggest that commitment to this particular value-

political party responsibility-is a function of experiencesoutside the League; thus

for example, those who are committed to the value do not prefer the League over

other organizations.For those holding this value, it appears the League is not an

identification group.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

482 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

values, as well as to the internalization of these skills and values,

the factor may also be thought to represent a dimension of

organizational socialization.

The isolation of this constellation of items identifies an impor-

tant dimension for further research. Knowledge and awareness of

group norms and values vary among group members and some

problems for further analysis are pointed up by Merton's question

"In which ways does group structure affect the distribution of

knowledge about the values and norms actually held by members

of the group?"20

Exclusiveness of Organizational Membership

Factor5 FactorF Item

Orthogonal Oblique No.

Rank Load- Load- Rank

ings ings

1. -.65 -.93 1 18 Number of other organizations in which

respondent is active: none"*. . four or

more

2. -.60 -.90 2 19 Number of other organizations in which

respondent holds office: none**. . .tthree

or more

3. .54 .47 4 76 Commitment score on soliciting funds

from the community: opposed.. .strongly

infavor* *

4. .49 .61 3 25 Preference for group discussion over

presented material: no,yes* *

5. .47 .33 5 24 Preference for group discussion over out-

side speakers: no,yes**

- .06 .32 6 47 Introjection: low. . .Ihigh**

This last factor loads heavily items on the number of organiza-

tions in which the respondent is active. The factor is mainly

indicative of a tendency toward exclusive membership in the

League. Items on this factor suggest that multiple organizational

membership is negatively related to commitment to the League

values of soliciting funds and group discussion. Both of these are

low-consensus values and both directly affect each individual mem-

ORobert K. Merton, Social Theory and Social Structure (Glencoe, Ill., 1957), p. 337.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT 483

ber. Two related hypotheses may account for the item loadings on

these values in this factor: (1) Those deeply involved in other

organizations may tend to view their League activities in limited

and utilitarian ways; they may prefer to get as much as they can

from the League without the additional time and energy required

by such activities as soliciting funds and group discussion. (9)

Other organizations may serve as alternative reference groups

which inhibit commitment to such values. Indeed, contrary prac-

tices in other organizations may be used as a justification for lack

of commitment, particularly where lack of commitment is a func-

tion of personal distaste in implementing the value. The majority

of women personally disliked to solicit funds, and many women

found group discussion methods frustrating and confessed they

sometimes preferred the direct presentation of factual material.

In such cases the individual can more legitimately justify her lack

of commitment by pointing out alternative practices in other

organizations than by expressions of personal dislike. By doing so

she is protected from the common rejoinder, "Well, if you were

really sold on the League, you wouldn't have any trouble selling

the League."

In any event, the qualitative data revealed a substantially large

group of women who seemed to typify what has been called the

"outsiders" and who belonged to a number of organizations.21

They are "in but not of} the organization. They approved of the

League and its activities but their primary loyalties were to other

organizations. These included the "political party actives," who

joined the League specifically to learn more about government;

community leaders concerned about schools or civil liberties, who

considered the League as an action organization that would help

them achieve rather specific desired ends; and women who "took"

the League rather than adult education or university extension

courses. Such cases involve a nonexclusive and utilitarian type of

membership where the organization is, in Turner's terms, more

frequently used as an "interaction" or "valuation" reference group

rather than as an "identification" group.22

21Alvin W. Gouldner, Cosmopolitans and Locals: Toward an Analysis of Latent

Social Roles-II, Administrative Science Quarterly, 2(1958), especially pp. 449-450.

22Groups whose members constitute merely conditions to an individual's actions

are defined as "interaction" reference groups; groups "which acquire value to the

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

484 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

INTERCORRELATIONS AMONG THE OBLIQUE

FACTORS

There can, of course, be no question of a correlation among

orthogonal factors since these are, by design, independent of each

other. Ordinarily however, there are correlations among oblique

factors, since these are not constructed so as to be independent of

each other, though they may turn out to be unrelated. In this anal-

ysis it has already been noted that there is a close congruence

between the oblique and orthogonal factors, and consequently

one should not expect that there will be high correlations among

the oblique factors. This is confirmed by Table 3 (see Appendix)

which indicates that correlations among the oblique factors are,

with certain exceptions, relatively low.23

One notable exception is the relation between Factor A, cos-

mopolitan integration, and a number of other dimensions. For

example, cosmopolitan integration is related to Factor B, introjec-

tion; that is, the degree to which individuals feel a part of varying

levels in the organization, particularly the higher levels, is positive-

ly related to the degree to which their self-image incorporates a

variety of organizationally approved qualities and values. This is

consistent with the earlier suggestion that both of these oblique

factors are derived from a splintering of the first very general inte-

gration factor yielded by the orthogonal solution.

The degree to which individuals feel a part of varying and

especially higher levels in the organization (cosmopolitan integra-

tion) is also related to the degree to which they are knowledgeable

about and aware of organizational policies (Factor E, organization-

al exposure) as well as to the degree to which they are committed

to the value of cross-sectionalmembership (Factor C). Finally, there

is a positive relation between Factor A (cosmopolitan integration)

and Factor F (exclusiveness of organizational membership)-if

individuals feel a part of varying and especially higher levels of the

organization, they are likely to belong to few or no other

organizations outside the League.

This last is a rather interesting and unexpected relationship,

individual because the standpoint of his identification groups designates them as

points of reference" might be called "valuation groups." See Turner, op. cit., p. 328.

23These correlations are not based upon correlations among the individuals' factor

scores, but derive directly from correlations among the factors themselves.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT 485

for in Factor A (cosmopolitan integration) items on multiple

organizational membership are positively loaded and are thus posi-

tively related to feeling a part of and being active in the League,

even though cosmopolitan integration is, as a whole, shown to

be related to few or no other memberships in organizations

outside the League when measured by Factor F (organizational

exclusiveness).

This suggests that active membership in a number of organiza-

tions outside of the League may have two quite different conse-

quences or implications. On the one hand, for some League women,

such outside activities may supplement and be integrated with

their activities in the League. These women may be those whose

organizational participation and whose leadership in one organi-

zation tend to pull them into a variety of organizations and an

expanding web of community functions. On the other hand, as

indicated in the earlier discussion of Factor F, membership in other

organizations may, for other women, imply a limited and utili-

tarian commitment to the League. The primary organizational

loyalties of these women may be elsewhere and their membership

in the League may be regarded by them as restricted to limited

educational or political purposes.

SUMMARY AND DISCUSSION

This paper reports on a factor analytic study of the dimensions

in organizational commitment among a group of women in the

League of Women Voters. Five orthogonal factors and six (pri-

mary) oblique factors were identified. The constellations of items

were similar in the orthogonal and oblique solutions.

Four of the oblique factors suggest various forms of organiza-

tional commitment.These include: cosmopolitan integration, the

degree to which the individual is active in and feels a part of the

varying levels of the particular organization, especially the higher

levels, and is active as well in other organizations; and organiza-

tional introjection, the degree to which the individual's ideal self-

image includes a variety of organizationally approved qualities

and values. These two oblique factors appear to be a breakdown

of a large, general integration factor obtained in the orthogonal

solution.

Two further commitment factors were identified as reflecting a

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

486 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

commitment to two specific organizational values, cross-sectional

membership and political party responsibility. The emergence of

these two factors lends support to the hypothesis that commitment

to the specific values of an organization is distinct from commit-

ment to the organization as a whole and further that commit-

ment to one organizational value is sometimes independent of

commitment to another.

The two remaining factors, or clusters of items, reflect (1) expo-

sure to organizational "culture"-knowledgeability and awareness

of organizational values and policies-and (2) exclusiveness of

organizational membership-organizational membership limited

to the particular organization.

Since various measures of participation have frequently been

used as indices of involvement or commitment to voluntary asso-

ciations, it is of interest here to indicate the relation of participa-

tion measures to other indices of commitment.24 In this study

questions on attendance at meetings and self-ratings on amount of

activity were heavily loaded on the cosmopolitan integration

factor. It is noteworthy, however, that holding office was loaded on

a different factor, the organizational introjection dimension. Thus

these two kinds of items, often used as measures of the same thing,

organizational commitment, actually seem to be measures reflect-

ing different kinds of organizational commitment.

This study has also raised some questions regarding Homan's

hypothesis that the higher an individual's rank in a group, the

more nearly his activities conform to the norms of that group.25

The elaboration of this hypothesis requires knowledge of the

kinds of norms and values to which an organizational elite conform

and those from which they may deviate.26The data here indicate

24See, for example, March, op. cit., especially pp. 735-736, and R. O. McWiiliams,

"A Study of the Relationship of Political Behavior to Social Group Membership"

(Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, 1953).

25For a complete statement of this hypothesis and a review of the literature see

Henry W. Riecken and George C. Homans, "Psychological Aspects of Social Struc-

ture," in Gardner Lindzey, ed., Handbook of Social Psychology (Cambridge, Mass.,

1954), II, especially 789-794. See also Norman Hilmar, "Conflicting Social Norms in

a Formal Organization: A Study of Interpersonal Expectations" (Ph.D. dissertation,

Cornell University, 1955).

26See March, op. cit. Riecken and Homans themselves point out, "It has often

been observed that very high ranking members of groups (e.g., members of aristoc-

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT 487

that commitment to some organizational values may be distinct

from participation, office holding, and integration-all of which

have been used, in addition to sociometric choice, as measures of

rank in testing Homan's hypothesis. The data suggest, further,

that it is among the organizational elite that some values, generally

taken for granted, are discussed and may become new issues.

The results of this research are, of course, highly tentative. The

sample is small and the context is limited. The study has, perhaps,

provided some first steps in identifying meaningful dimensions

of group commitment, a problem which is at the very core of

sociology.

racies, oligarchies, or other powerful classes), who have a secure social position, do

not conform as strictly to some group norms as do individuals of middle rank, nor

are they subjected to serious pressure to conform..." (op. cit., p. 793).

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

488 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

APPENDIX

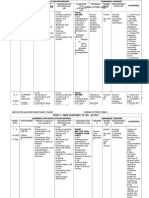

Table 1. Orthogonal factor matrix.

Item 1 2 3 4 5 6 7*

16. Attendance, branch meetings .72 -.14 -.08 .14 -.02 .08 -.23

17. Attendance, League Day .77 .05 .08 .07 .06 .13 -.34

18. No. organizations, active -.03 -.07 .09 -.21 -.65 .31 .12

19. No. organizations, hold office .06 -.06 -.08 -.08 -.60 .32 .05

20. Give up time in other organizations .54 .13 -.30 -.19 .02 -.17 .04

21. Give up social life .21 .29 -.21 -.17 -.23 -.22 .42

24. Prefer group discussion over outside

speakers .41 .13 -.01 -.15 .47 .16 .14

25. Prefer group discussion over presented

material .25 -.11 .18 -.20 .49 -.15 .03

26. Enthusiasm for League .66 .14 .03 .02 -.03 -.20 .20

27. Rather belong to League than other or-

ganizations .46 .01 -.36 .20 .29 .01 .23

28. Confidence in League achieving goals .09 .21 -.35 .07 -.21 -.24 .17

29. Feel part of branch group .74 .05 -.01 .09 -.11 -.25 .15

30. Feel part of city League .90 .10 -.01 -.01 -.01 .02 .08

31. Feel part of state League .77 -.02 -.04 -.12 .10 .16 .15

32. Feel part of nat'l League .72 -.01 -.13 -.11 -.05 .15 .12

41. Highest office held .67 .26 .20 .07 -.10 -.20 -.23

43. Extent of activity .82 .01 .06 .11 .02 .08 -.12

46. Friendship vs. educational aims for

League -.06 -.22 .00 -.27 -.10 -.18 -.33

47. Introjection .62 .38 .22 -.01 .06 -.39 .03

48. Type of argument, csmt .34 .31 -.13 .51 -.02 -.18 -.10

49. No. qualifications, csm -.12 -.64 .08 .16 -.10 -.30 .08

52. Discussed csmwith League members .57 -.20 .16 .38 .09 .21 -.16

55. Private doubts, csm -.14 -.53 -.10 .05 .12 -.39 .26

56. Commitment, csm .29 .74 -.10 -.02 .05 .23 -.10

57. Personal importance, csm .20 .72 .02 .01 -.02 .26 .05

58. Type of argument, ppr t .26 -.06 .37 .61 .06 .10 .08

59. No. qualifications, ppr .03 .03 -.62 .09 .03 -.05 -.31

62. Discussed ppr with League members .14 -.05 -.02 .63 .11 -.12 .00

65. Private doubts, ppr .03 .13 -.66 .06 .04 -.12 .01

*The nature of this factor is obscure. It is certainly related to the value of soliciting

funds, and, possibly, some form of commitment to this value. However, we have been

able to advance no satisfactory hypothesis to account for the particular combination

of items in the factor. Since discussion of the factor would necessarily involve at this

time only a series of ad hoc explanations, the factor has not been included in the main

analysis. Part of the difficulty may be related to the fact that soliciting funds was a low-

consensus value, which at the time of the study was the object of much conflict and

discussion.

tSpecific League value, cross-sectional membership.

tSpecific League value, political party responsibility.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

ORGANIZATIONAL COMMITMENT 489

Table 1 (concluded).

Item 1 2 3 4 5 6 7*

66. Commitment, ppr .27 .07 .61 .25 .13 .33 .07

67. Personal importance, ppr .17 -.03 .62 .29 -.04 -.12 -.09

68. Type of argument, sfc? .37 -.02 .03 .52 .28 .16 -.14

69. No. qualifications, sfc .05 -.13 .24 .05 -.11 -.23 .57

72. Discussed sfc with League members .38 .00 .18 .51 .12 -.23 .15

75. Private doubts, sfc -.18 -.20 .05 .00 -.03 .00 .61

76. Commitment, sfc .41 .12 .02 .16 .54 .16 -.07

77. Personal importance, sfc .33 .23 -.09 .04 .02 -.06 -.54

C25. Objectivity, csm -.07 -.19 .01 .62 .02 -.18 .12

C30. Awareness csm as League value .52 .29 .40 .05 .24 -.16 .01

C34. Objectivity, ppr .00 .23 -.13 .26 .15 .19 .22

C43. Objectivity, sfc -.06 .02 -.02 -.01 .00 .14 .59

?Specific League value, soliciting funds from the community.

Table2. Primary factor pattern.

Item A B C D E F G*

16. Attendance, branch meetings .84 -.05 -.16 -.12 .10 -.20 -.26

17. Attendance, League Day .73 .08 .05 .06 -.01 -.09 -.35

18. No. organizations, active .46 -.19 .07 .20 -.18 -.93 .16

19. No. organizations, hold office .55 -.29 .07 .00 -.04 -.90 .07

20. Give up time in other organizations .44 .25 -.01 -.35 -.18 .08 -.05

21. Give up social life .05 .39 .15 -.20 -.08 -.12 .36

24. Prefers group discussion over outside

speakers .52 -.12 -.06 .03 -.26 .33 .13

25. Prefers group discussion over presented

material .07 .23 -.18 .16 -.29 .61 .02

26. Enthusiasm for League .42 .45 -.01 .02 .04 .02 .17

27. Rather belong to League than other or-

ganizations .45 -.11 -.02 -.36 .19 .20 .19

28. Confidence in League achieving goals -.07 .20 .07 -.40 .18 -.09 .11

29. Feel part of branch group .53 .45 -.13 -.04 .13 -.06 .12

30. Feel part of city League .84 .26 .04 .00 -.05 -.13 .05

31. Feel part of state League .90 .04 .00 .00 -.18 -.10 .13

32. Feel part of national League .91 .00 .00 -.09 -.15 -.26 .09

41. Highest office held .27 .56 .10 .15 .07 .01 -.25

43. Extent of activity .81 .11 -.03 .05 .06 -.13 -.13

46. Friendship vs. educational aims for

League .03 .07 -.31 -.08 -.28 .01 -.36

*See discussion of Factor 7, Table 1.

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

490 ADMINISTRATIVE SCIENCE QUARTERLY

Table2 (concluded).

Item A B C D E F G*

47. Introjection -.01 .82 .15 .17 .00 .32 .00

48. Type of argument, csmt -.09 .24 .20 -.20 .57 .08 -.13

49. No. qualifications, csm .07 -.05 -.76 .01 .22 -.03 .11

52. Discussed csmwith League members .67 -.18 -.12 .17 .32 -.15 -.12

55. Private doubts, csm -.05 .02 -.69 -.18 .11 .28 .25

56. Commitment, csm -.05 .17 .81 -.05 -.06 .01 -.13

57. Personal importance, csm -.11 .18 .82 .11 -.01 -.08 .05

58. Type of argument, ppr .10 .01 .00 .40 .61 -.06 .17

59. No. qualifications, ppr .11 -.27 -.02 -.73 .12 .04 -.41

62. Discussed ppr with League members -.09 -.02 -.10 -.08 .68 .14 .02

65. Private doubts, ppr .03 -.14 .04 -.74 .13 .10 -.10

66. Commitment, ppr .17 .04 .24 .73 .16 -.07 .18

67. Personal importance, ppr -.15 .38 -.08 .63 .28 .03 .00

68. Type of argument, sfc? .27 -.19 .04 .02 .47 .14 -.11

69. No. qualifications, sfc -.04 .33 -.22 .29 .12 -.03 .61

72. Discussed sfcwith League members .04 .30 -.13 .10 .57 -.03 -.12

75. Private doubts, sfc -.01 -.06 -.16 .13 .04 -.09 .65

76. Commitment, sfc .23 -.05 .18 .03 .05 .47 -.08

77. Personal importance, sfc .10 .15 .15 -.18 .02 .09 -.59

C25. Objectivity, csm -.22 -.04 -.24 -.04 .70 .07 .15

C30. Awareness csmas League value .00 .58 .18 .40 .00 .38 .03

C34. Objectivity, ppr -.06 -.17 .32 -.07 .25 .05 .23

C43. Objectivity, sfc .09 -.09 .10 .10 .00 -.12 .62

tSpecific League value, cross-sectional membership.

tSpecific League value, political party responsibility.

?Specific League value, soliciting funds from the community.

Table3. Correlations among the primary factors.

A B C D E F G

A 1.00

B .35 1.00

C .38 .12 1.00

D .10 -.25 -.09 1.00

E .40 .13 .16 .16 1.00

F .53 -.15 .23 .19 .27 1.00

G -.10 -.04 -.03 -.27 -.14 .01 1.00

This content downloaded from 195.34.79.192 on Sat, 14 Jun 2014 18:19:00 PM

All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

You might also like

- Field Study 4 Complete EpisodeDocument111 pagesField Study 4 Complete EpisodeJoy Manatad90% (30)

- Organizational Structure and Culture. Hofstede S Four DimensionsDocument13 pagesOrganizational Structure and Culture. Hofstede S Four DimensionsDes Arenas80% (5)

- Incentive Systems: A Theory of OrganizationsDocument39 pagesIncentive Systems: A Theory of OrganizationsNikolina B.No ratings yet

- LESSON PLAN (2017-2018) : Topic: Conversion of TimberDocument3 pagesLESSON PLAN (2017-2018) : Topic: Conversion of Timberapi-341095505100% (1)

- Gender SensitivityDocument2 pagesGender Sensitivityapi-370456296% (26)

- This Content Downloaded From 85.201.97.108 On Tue, 11 Apr 2023 22:06:27 UTCDocument24 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 85.201.97.108 On Tue, 11 Apr 2023 22:06:27 UTCArno Vander SyppeNo ratings yet

- Status and Action How Stratification Affects The Protest Participation of Young AdultsDocument16 pagesStatus and Action How Stratification Affects The Protest Participation of Young Adultsrein_nantesNo ratings yet

- Kenneth T. 2010Document53 pagesKenneth T. 2010Dr-Rahib AliNo ratings yet

- Cho and Auger (2017)Document9 pagesCho and Auger (2017)Rui ZhangNo ratings yet

- 10 - March J. G., 1958, OrganizationsDocument4 pages10 - March J. G., 1958, OrganizationsLe Thi Mai ChiNo ratings yet

- Identified and Introjected Forms of Political Internalization: Extending Self-Determination TheoryDocument12 pagesIdentified and Introjected Forms of Political Internalization: Extending Self-Determination TheoryLeon AshleyNo ratings yet

- Buzoida (2014) The Semiology Analysis in Media StudiesDocument11 pagesBuzoida (2014) The Semiology Analysis in Media StudiesRăzvanCristianNo ratings yet

- This Content Downloaded From 212.252.137.164 On Sat, 31 Oct 2020 14:32:34 UTCDocument27 pagesThis Content Downloaded From 212.252.137.164 On Sat, 31 Oct 2020 14:32:34 UTCDetay DanismanlikNo ratings yet

- (1994) - Organizational Socialization - Its Content and Consequences PDFDocument14 pages(1994) - Organizational Socialization - Its Content and Consequences PDFJoana CarvalhoNo ratings yet

- Self Measures For Love and Compassion Research TRUSTDocument11 pagesSelf Measures For Love and Compassion Research TRUSTZenobia NiculitaNo ratings yet

- Hybrid ActivismDocument58 pagesHybrid ActivismAninda DuttaNo ratings yet

- J Organ Behavior - March 1992 - Mael - Alumni and Their Alma Mater A Partial Test of The Reformulated Model ofDocument21 pagesJ Organ Behavior - March 1992 - Mael - Alumni and Their Alma Mater A Partial Test of The Reformulated Model ofjmfernando1991No ratings yet

- srtEmotionsCollectiveEvents FinalVersionDocument36 pagessrtEmotionsCollectiveEvents FinalVersionTomasSaavedraNo ratings yet

- Chapter No 1Document27 pagesChapter No 1Iqra AnsariNo ratings yet

- Collins (2020) Psychological and Political LiberaionDocument18 pagesCollins (2020) Psychological and Political LiberaionnicoleheNo ratings yet

- Who Is Motivated To Volunteer? A Latent Profile Analysis Linking Volunteer Motivation To Frequency of VolunteeringDocument23 pagesWho Is Motivated To Volunteer? A Latent Profile Analysis Linking Volunteer Motivation To Frequency of Volunteeringminhot525No ratings yet

- Pers Soc Psychol Bull 2006 Jetten 162 73Document13 pagesPers Soc Psychol Bull 2006 Jetten 162 73Suciu PaulNo ratings yet

- Daniel KatzDocument14 pagesDaniel Katznouar1988No ratings yet

- Johnson NGOResearchProgram 2007Document21 pagesJohnson NGOResearchProgram 2007baraNo ratings yet

- Barge&Schlueter - Memorable Messages and Newcomer SocializationDocument25 pagesBarge&Schlueter - Memorable Messages and Newcomer SocializationIoana IoaNo ratings yet

- Party Brands and Partisanship: Theory With Evidence From A Survey Experiment in ArgentinaDocument16 pagesParty Brands and Partisanship: Theory With Evidence From A Survey Experiment in ArgentinaKeys78No ratings yet

- The Concept of Social CohesionDocument19 pagesThe Concept of Social CohesionRobert GilmoreNo ratings yet

- Intergroup Relatios Across CultureDocument6 pagesIntergroup Relatios Across CultureAmmara Haq100% (1)

- The Organization-Set Toward A Theory of Interorganizational RelationsDocument15 pagesThe Organization-Set Toward A Theory of Interorganizational RelationsClaude BerthiaumeNo ratings yet

- Recruitment Strategies, Ideology, and Organization in The Hare Krishna MovementDocument13 pagesRecruitment Strategies, Ideology, and Organization in The Hare Krishna MovementDavide GiaquintoNo ratings yet

- GerbasiandPrenticeJPSP2013 (1)Document66 pagesGerbasiandPrenticeJPSP2013 (1)anchujaglanNo ratings yet

- The Relationship Between Sense of Community and Psychological Wellbeing Among UndergraduatesDocument12 pagesThe Relationship Between Sense of Community and Psychological Wellbeing Among UndergraduatesAakanksha VermaNo ratings yet

- Social and Economic Exchange Construct DevelopmentDocument32 pagesSocial and Economic Exchange Construct DevelopmentNurul MutmainnahNo ratings yet

- Sekala and Niskala Accountability Practices in The Clan-Based Organization MGPSSR in Bali, IndonesiaDocument5 pagesSekala and Niskala Accountability Practices in The Clan-Based Organization MGPSSR in Bali, Indonesiarobert0rojerNo ratings yet

- Altruistic Behavior and Inter-Personal Trust PaperDocument8 pagesAltruistic Behavior and Inter-Personal Trust Papernasrina1991faoziaNo ratings yet

- Predicting Organizational Commitment: The Role of Religiosity and Ethical IdeologyDocument25 pagesPredicting Organizational Commitment: The Role of Religiosity and Ethical IdeologyJohna Mae Dolar EtangNo ratings yet

- Suhay ExplainingGroupInfluence 2015Document32 pagesSuhay ExplainingGroupInfluence 2015Sandra Carolina ValenciaNo ratings yet

- Ed 421 956 He 031 494Document18 pagesEd 421 956 He 031 494John Mark CartasanoNo ratings yet

- Voluntary Organizations: Commitment, Leadership, and Organizational EffectivenessDocument8 pagesVoluntary Organizations: Commitment, Leadership, and Organizational EffectivenessMogahed OsmanNo ratings yet

- Inter-relationship of Sociology and Other Social GroupDocument4 pagesInter-relationship of Sociology and Other Social Groupdawodumunirat3No ratings yet

- Wiener e Vardi (1990)Document12 pagesWiener e Vardi (1990)Vinícius RennóNo ratings yet

- Stereotyping From The Perspective of Perceivers and TargetsDocument10 pagesStereotyping From The Perspective of Perceivers and TargetsFatur RahmatNo ratings yet

- Shaping The Shareholder Activism Agenda: Institutional Investors and Global Social IssuesDocument26 pagesShaping The Shareholder Activism Agenda: Institutional Investors and Global Social Issuesahmed sharkasNo ratings yet

- Gray & Silbey 2014 Governing Inside the Orga - Interpreting Regulation & Compliance AJSDocument51 pagesGray & Silbey 2014 Governing Inside the Orga - Interpreting Regulation & Compliance AJSRosa LuxemburgNo ratings yet

- Typology of Voluntary AssociationsDocument9 pagesTypology of Voluntary AssociationsFoteini PanaNo ratings yet

- Leat 2005 Theories - of - Change PDFDocument16 pagesLeat 2005 Theories - of - Change PDFmsfts.No ratings yet

- The Theory of Political PropagandaDocument6 pagesThe Theory of Political Propaganda温雪儿No ratings yet

- Lecture 1 - PMS 4001 Organizational CommunicationDocument67 pagesLecture 1 - PMS 4001 Organizational Communicationwenbaolong9No ratings yet

- Sample Qualitative Assignment - 9.25.24Document3 pagesSample Qualitative Assignment - 9.25.24makyboy2003No ratings yet

- 1978 - AveniOrganizational Linkages and RM The Significance of Linkage Strength and BreadthDocument19 pages1978 - AveniOrganizational Linkages and RM The Significance of Linkage Strength and BreadthMireia PéNo ratings yet

- Levinson 1965Document22 pagesLevinson 1965wslou2022No ratings yet

- Trust and Reciprocity in Intergroup Relations: Differing Perspectives and BehaviorsDocument6 pagesTrust and Reciprocity in Intergroup Relations: Differing Perspectives and BehaviorsDonatoNo ratings yet

- Bednar, J (2022) - Putting Identification in Motion A Dynamic View of Organizational Identification. Organization Science PDFDocument25 pagesBednar, J (2022) - Putting Identification in Motion A Dynamic View of Organizational Identification. Organization Science PDFValentina FaúndezNo ratings yet

- Final Project OB (7145)Document10 pagesFinal Project OB (7145)Annie MehmoodNo ratings yet

- GROSS - Universities As OrganizationsDocument28 pagesGROSS - Universities As OrganizationsMaria Caramez CarlottoNo ratings yet

- Libraries As Organisations PDFDocument15 pagesLibraries As Organisations PDFlibrarianNo ratings yet

- Empowerment Theory, Research, and Application: Douglas D. PerkinsDocument14 pagesEmpowerment Theory, Research, and Application: Douglas D. PerkinsmbabluNo ratings yet

- DIVERSITYDocument17 pagesDIVERSITYBantihun GetahunNo ratings yet

- PoliticsDocument23 pagesPoliticsHarsimrat BaliNo ratings yet

- Social Identity TheoryDocument18 pagesSocial Identity TheoryMarie MardaleishviliNo ratings yet

- A Theory of Social IntegrationDocument13 pagesA Theory of Social IntegrationZaw HtetNo ratings yet

- Fake News Essay Outline PDFDocument2 pagesFake News Essay Outline PDFGarry ChiuNo ratings yet

- Core Values of DevelopmentDocument9 pagesCore Values of DevelopmentChristopher Celis100% (1)

- Assignment 1Document3 pagesAssignment 1Clint HarryNo ratings yet

- Lesson Plan 6 PRDocument4 pagesLesson Plan 6 PRapi-478264736No ratings yet

- SociiologyDocument224 pagesSociiologyChetan MittalNo ratings yet

- SMK Sultan Alauddin Riayat Shah 1, Pagoh Scheme of Work (Form 5)Document13 pagesSMK Sultan Alauddin Riayat Shah 1, Pagoh Scheme of Work (Form 5)abdlatifabhamidNo ratings yet

- Question Bank Civics 7Document2 pagesQuestion Bank Civics 7Honey RattanNo ratings yet

- Business EthicsDocument1 pageBusiness Ethicsbernadeth quintanaNo ratings yet

- Diversity Lesson PlanDocument15 pagesDiversity Lesson PlanKatie BethellNo ratings yet

- Understanding The SelfDocument7 pagesUnderstanding The Selfjuan miguel lapidezNo ratings yet

- The Sweet Spot DraftDocument2 pagesThe Sweet Spot DraftMatt8716No ratings yet

- Arabic 1 (MC)Document6 pagesArabic 1 (MC)ainabalqis roslyNo ratings yet

- MODULE q2 Grade 8 1st Week ArtsDocument4 pagesMODULE q2 Grade 8 1st Week ArtsIsrael Marquez100% (2)

- The Fadiah Files - Fadiah Nadwa FikriDocument4 pagesThe Fadiah Files - Fadiah Nadwa FikriSweetCharity77No ratings yet

- ApresionalDocument59 pagesApresionalFama LaNo ratings yet

- Chinese Martial ArtsDocument5 pagesChinese Martial ArtsAanand K PottyNo ratings yet

- UNIT MMH 753Document12 pagesUNIT MMH 753Kaur JotNo ratings yet

- Model of Educational ManagementDocument13 pagesModel of Educational ManagementAnonymous jh2hb0uul100% (3)

- OBJ Datastream PDFDocument272 pagesOBJ Datastream PDFRamakrishna AnnavazzalaNo ratings yet

- P3 Methods of PhilosophizingDocument43 pagesP3 Methods of PhilosophizingAnne MoralesNo ratings yet

- Arte OceaniaDocument8 pagesArte OceaniaRQL83appNo ratings yet

- Robertkelemensoc 322 ResearchpaperDocument9 pagesRobertkelemensoc 322 Researchpaperapi-285846507No ratings yet

- Education For TransgenderDocument15 pagesEducation For TransgenderPoulomi Mandal100% (1)

- Speech & Language Development: CSCD 3301 Felicidad Garcia, PHD, CCC-SLPDocument17 pagesSpeech & Language Development: CSCD 3301 Felicidad Garcia, PHD, CCC-SLPHannah BraidNo ratings yet

- Dubbing and Subtitling The Dubbing and Subtling IndustriesDocument3 pagesDubbing and Subtitling The Dubbing and Subtling IndustriesIsaí MuñozNo ratings yet

- Navigating Pathways: Five Core CompetenciesDocument2 pagesNavigating Pathways: Five Core CompetenciesAkanksha RamakrishnaNo ratings yet

- 7 Different Types of Catering Services You NeedDocument17 pages7 Different Types of Catering Services You NeedEstela SaludNo ratings yet