4 4C61 9667 890a8c942a2b PDF

4 4C61 9667 890a8c942a2b PDF

Uploaded by

Radha CharpotaCopyright:

Available Formats

4 4C61 9667 890a8c942a2b PDF

4 4C61 9667 890a8c942a2b PDF

Uploaded by

Radha CharpotaOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

4 4C61 9667 890a8c942a2b PDF

4 4C61 9667 890a8c942a2b PDF

Uploaded by

Radha CharpotaCopyright:

Available Formats

TORT OF CONSPIRACY

Pragya Rakshita & Pratikesh Shankar1

Abstract:

In this paper, the authors explore the law of tort of conspiracy as applied in India. Tort came to

India during the British rule, but is still highly underdeveloped in its recognition and application.

Many Indian lawyers and academicians, erroneously, do not even consider the law of torts as

applicable in India. Through this paper, the authors have attempted to burst this myth and display

the importance of tort law, by focusing on one of its facets, that of the tort of conspiracy.

Conspiracy is both a crime as well as a tort in India. In this paper, the tort of conspiracy is deeply

discussed after a brief overview of criminal conspiracy. The authors have also attempted to find

out the lacunae in the tort of conspiracy as applied in India and made suggestions accordingly.

Keywords: Tort, Conspiracy, Criminal Conspiracy

1

3rd Year, National University of Study and Research in Law, Ranchi.

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

TABLE OF CONTENTS

I. TORT- EVOLUTION AND SCOPE

A. TORT AGAINST PROPERTY

B. PHYSICAL TORT

C. PSYCHIATRIC TORT

D. ECONOMIC TORT

E. TORT AGAINST REPUTATION

II. CRIMINAL CONSPIRACY

III. TORT OF CONSPIRACY

A. ESSENTIALS OF TORT OF CONSPIRACY

1. INTENTION

2. COMBINATION

3. OVERT ACT

B. TYPES OF TORT OF CONSPIRACY

1. CONSPIRACY TO INJURE- “CROFTER” CONSPIRACY

2. “UNLAWFUL MEANS” CONSPIRACY

IV. COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF CONSPIRACY AS CRIME AND AS TORT

A. OVERT ACT

B. CONSPIRACY BETWEEN HUSBAND AND WIFE

C. RESTRICTIONS

V. CASE LAWS IN TORT OF CONSPIRACY

VI. CONCLUSION

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

TORT- EVOLUTION AND SCOPE

The word „tort‟ comes from the Latin root „tortum‟ or „tortus‟, which means „twist‟ or „crooked‟.

Tort is a French word which means, in its etymological sense, a „twisting out‟ and in a popular

sense, a crooked act, a transgression from straight or right conduct, a wrong. In generic sense, it

was introduced into the terminology of English law by the French speaking lawyers and judges

of the courts of the Norman and Angevin Kings of England.

A tort is a civil wrong the remedy for which is a legal action in the nature of a suit, for

unliquidated damages. It is not exclusively the breach of a contract or the breach of trust, or the

breach of other nearly equitable obligations. It means a wrong or injury which has certain

characteristics, the most important of which is that it is redressable in an action for damages at

the instance of the person wronged or injured.

The law of tort developed from the maxim of „Ubi Jus Ibi Remedium‟, which means, „where

there is a right, there is a remedy‟. This maxim further expanded into the maxims of „Damnum

sine Injuria‟ and „Injuria sine Damnum‟. These maxims mean that whenever there is injury i.e.

infringement of legal right, there is a remedy, immaterial of the fact that whether there is

substantial damage or not. Whenever there is violation of any legal right in any form, there will

be a remedy provided under tort.

The law of tort evolved from the common law principle. It was prevalent in England and it came

to India when India was a colony of the British. In British India, the first courts were established

in the presidency towns of Madras, Bombay and Calcutta, and they were required to adopt the

English common law of torts in force at that time in Britain, to their Indian jurisdiction. As for

other courts that were established by local acts, the local acts contained a section that required

them to act in accordance with „justice, equity and good conscience‟ in cases of non-specific law

or usage.

In English law, a tort is a civil wrong, as distinguished from a criminal wrong. Some of the

features of the law of torts which were developed in England are absent in India. Tort law is not

codified in India. It has also been noted that in the Union Carbide Case, that Section 9 of the

Code of Civil Procedure, 1908, which enables a Civil Court to try all suits of civil nature,

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

impliedly confers jurisdiction to apply the law of torts as principle of justice, equity, and good

conscience.

The English law of torts was modified according to its suitability to Indian conditions, so as to

make it applicable to modern India. It was further modified by the Indian legislature through

various Acts and statutes. Thus, the law of torts in India is almost wholly the English law which

is administered as per the rules of justice, equity and good conscience.2

The law of torts relates to the recognition of interests of the civil law recognizes in the absence of

contractual relation between the wrongdoer and the injured person. The interests of injured

person may be grouped into the following categories: property, physical, psychiatric, economic

and reputation.

TORT AGAINST PROPERTY:

In legal usage, property means an interest or right over something, such as the right to

ownership, right to possession, or the right to dispose. A tort against property is committed when

any person harms or injures such rights of another over his property. Some examples of tort

against property are trespass, nuisance and conversion.

PHYSICAL TORT:

Physical tort means a wrong against or injury caused to the physical body of a person, such as

the torts of assault, battery or false imprisonment.

PSYCHIATRIC TORT:

The emotional and mental well being of a person is essential for maintaining overall health, and

so the law also condemns any injury to the mental and emotional well being of a person. Any tort

that causes such mental and emotional injury falls under the category of psychiatric tort, such as

intentional infliction of emotional distress.

2

RATANLAL & DHIRAJLAL, THE LAW OF TORTS, (Akshay Sapre ed., 27th ed. 2016).

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

ECONOMIC TORT:

Any injury or harm to the financial well being or prosperity of any person is categorized as

economic tort, and an important example of this is fraud.

TORT AGAINST REPUTATION:

In simple words, the reputation of a person is the image of that person in the minds of the right-

thinking members of society, and any harm to that falls under this category. The tort of

defamation is an example of this kind of tort.

In this research paper, the tort of conspiracy will be discussed in detail. Conspiracy is both a tort

as well as a crime, so to better understand the tort of conspiracy, it is essential to briefly discuss

criminal conspiracy as well.

CRIMINAL CONSPIRACY

In India, conspiracy was initially only considered as a civil wrong, but later on it was brought

under the ambit of Indian Criminal Law. Conspiracy was not an offence under the Indian Penal

Code, 1860 (hereinafter referred to as the IPC) until the Criminal Law Amendment Act of 1913

was passed which added the Sections 120A and 120B to the IPC

Section 120A of the IPC state that:

“Definition of criminal conspiracy- When two or more persons agree to do, or cause to be done,-

(1) an illegal act, or

(2) an act which is not illegal by illegal means, such an agreement is designated a criminal

conspiracy:

Provided that no agreement except an agreement to commit an offence shall amount to a

criminal conspiracy unless some act besides the agreement is done by one or more parties to

such agreement in pursuance thereof.

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

Explanation- It is immaterial whether the illegal act is the ultimate object of such agreement, or

is merely incidental to that object.”

Section 120B of the said Code states that:

“Punishment of criminal conspiracy.—

(1) Whoever is a party to a criminal conspiracy to commit an offence punishable with death,

2[imprisonment for life] or rigorous imprisonment for a term of two years or upwards, shall,

where no express provision is made in this Code for the punishment of such a conspiracy, be

punished in the same manner as if he had abetted such offence.

(2) Whoever is a party to a criminal conspiracy other than a criminal conspiracy to commit an

offence punishable as aforesaid shall be punished with imprisonment of either description for a

term not exceeding six months, or with fine or with both.”

So, while Section 120A of the IPC provides the definition of criminal conspiracy, Section 120B

of the Code provides the punishment for the same.

The essentials of criminal conspiracy are3-

a) an object to be accomplished,

b) a plan or scheme embodying means to accomplish that object,

c) an agreement or understanding between two or more of the accused persons whereby, they

become definitely committed to cooperate for the accomplishment of the object by the means

embodied in the agreement, or by any effectual means, and

d) in the jurisdiction where the statute required an overt act.

The Law Commission of India has given the following definition for Criminal Conspiracy-

When two or more persons agree to commit an offence punishable with death, imprisonment for

life, or imprisonment of either description for a term of two years or upwards, or to cause such an

offence to be committed, the agreement is designated a criminal conspiracy.

3

Ram Narayan Popli v. C.B.I, (2003) 3 SCC 641.

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

In the very recent case of Rajiv Kumar v. State of U.P.4, the essential ingredients of the crime of

conspiracy were discussed. They were enumerated as, “(i) an agreement between two or more

persons; (ii) the agreement must relate to doing or causing to be done either (a) an illegal act;

or (b) an act which is not illegal in itself but is done by illegal means. It is, therefore, plain that

meeting of minds of two or more persons for doing or causing to be done an illegal act or an act

by illegal means is sine qua non of criminal conspiracy.”

The crime of conspiracy is quite separate from the crime itself for which the conspiracy was

formulated, and it is also separately and independently punishable. This distinction was

explained in the case of Leo Roy Frey v. Suppdt. Distt. Jail5, where it was said that, “The offence

of conspiracy to commit a crime is different offence from the crime that is the object of the

conspiracy because the conspiracy precedes the commission of the crime and is complete before

the crime is attempted or completed. Equally the crime attempted or completed does not require

the element of conspiracy as one of its ingredients. They are, therefore quite separate offences.”

Another rule of criminal conspiracy was discussed in the case of State of Maharashtra & Ors. v.

Som Nath Thapa & Ors.6, where it was observed that, “for a person to conspire with another, he

must have knowledge of what the co-conspirators were wanting to achieve and thereafter having

the intent to further the illegal act takes recourse to a course of conduct to achieve the illegal

end or facilitate its accomplishment.”

The Supreme Court in State v. Nalini7 (Rajiv Gandhi Assassination case), dealt at length with the

law of conspiracy and laid down the following broad principles governing the law of conspiracy:

1. Under S. 120A IPC offence of criminal conspiracy is committed when two or more persons

agree to do or cause to be done an illegal act or legal act by illegal means. When it is a legal

act by illegal means overt act is necessary. Offence of criminal conspiracy is an exception to

the general law where intent alone does not constitute a crime. It is intention to commit

crime and joining hands with persons having the same intention. Not only the intention but

there has to be agreement to carry out the object of the intention, which is an offence. It

4

(2017) 8 SCC 791.

5

AIR 1958 SC 119.

6

(1996) 4 SCC 659.

7

(1999) 5 SCC 253.

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

would not be enough for the offence of conspiracy when some of the accused merely

entertained a wish, howsoever horrendous it may be, that offence be committed.

2. Acts subsequent to the achieving of the object of conspiracy may tend to prove that a

particular accused was party to the conspiracy. Once the object of conspiracy has been

achieved, any subsequent act, which may be unlawful, would not make the accused a part of

the conspiracy like giving shelter to an absconder.

3. Conspiracy is hatched in private or in secrecy. It is rarely possible to establish a conspiracy

by direct evidence. Usually, both the existence of the conspiracy and its objects have to be

inferred from the circumstances and the conduct of the accused.

4. Conspirators may, for example be enrolled in a chain - A enrolling B, B enrolling C, and so

on; and all will be members of a single conspiracy if they so intend and agree, even though

each member knows only the person who enrolled him and the person whom he enrolls.

There may be a kind of umbrella spoke enrolment, where the single person at the center does

the enrolling and all the other members are unknown to each other, though they know that

there are to be other members. These are theories and in practice it may be difficult to tell

which conspiracy in a particular case falls into which category. It may, however even

overlap. But then there has to be present mutual interest. Persons may be members of single

conspiracy even though each is ignorant of the identity of many others who may have diverse

roles to play. It is not a part of the crime of conspiracy that all the conspirators need to agree

to play the same or an active role.

5. When two or more persons agree to commit a crime of conspiracy, then regardless of making

or considering any plans for its commission, and despite the fact that no step is taken by any

such person to carry out their common purpose, a crime is committed by each and every one

who joins in the agreement. There has thus to be two conspirators and there may be more

than that. To prove the charge of conspiracy, it is not necessary that intended crime was

committed or not. If committed it may further help prosecution to prove the charge of

conspiracy.

6. It is not necessary that all conspirators should agree to the common purpose at the same

time. They may join with other conspirators at any time before the consummation of the

intended objective, and all are equally responsible. What part each conspirator is to play

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

may not be known to everyone or the fact as to when a conspirator joined the conspiracy and

when he left.

7. A charge of conspiracy may prejudice the accused because it forces them into a joint trial

and the court may consider the entire mass of evidence against every accused. Prosecution

has to produce evidence not only to show that each of the accused has knowledge of the

object of conspiracy but also of the agreement. In the charge of conspiracy the court has to

guard itself against the danger of unfairness against the accused. Introduction of evidence

against some may result in the conviction of all, which is to be avoided. By means of

evidence in conspiracy, which is otherwise inadmissible in the trial of any other substantive

offence, prosecution tries to implicate the accused not only in the conspiracy itself but also in

the substantive crime of the alleged conspirators. There is always difficulty in tracing the

precise contribution of each member of the conspiracy but then there has to be cogent and

convincing evidence against each one of the accused charged with the offence of conspiracy.

8. It is the unlawful agreement and not its-accomplishment, which is the gist or essence of the

crime of conspiracy. Offence of criminal conspiracy is complete even though there is no

agreement as to the means by which the purpose is to be accomplished. It is the unlawful

agreement which is the gravemen of the crime of conspiracy. The unlawful agreement which

amounts to a conspiracy need not be formal or express, but may be inherent in and inferred

from the circumstances, especially declarations, acts and conduct of the conspirators. The

agreement need not be entered into by all the parties to it at the same time, but may be

reached by successive actions evidencing their joining of the conspiracy.

9. It has been said that a criminal conspiracy is a partnership in crime, and there is in each

conspiracy a joint or mutual agency for the prosecution of a common plan. Thus, if two or

more persons enter into a conspiracy, any act done by any of them pursuant to the agreement

is, in contemplation of law, the act of each of them and they are jointly responsible therefor.

This means that everything said, written or done by any of the conspirators in execution or in

furtherance of the common purpose is deemed to have been said, done or written by each of

them. And this joint responsibility extends not only to what is done by any of the conspirators

pursuant to the original agreement but also to collateral acts incidental to and growing out

of the original purpose. A conspirator is not responsible, however, for acts done by a co-

conspirator after termination of the conspiracy. The joinder of a conspiracy by a new

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

member does not create a new conspiracy nor does it change the status of the other

conspirators, and the mere fact that conspirators individually or in groups perform different

tasks to a common end does not split up a conspiracy into several different conspiracies.

10. A man may join a conspiracy by word or by deed. However, criminal responsibility for a

conspiracy requires more than a merely passive attitude towards an existing conspiracy. One

who commits an overt act with knowledge of the conspiracy is guilty. And one who tacitly

consents to the object of a conspiracy and goes along with other conspirators, actually

standing by while the others put the conspiracy into effect, is guilty though he intends to take

no active part in the crime.

The offence of criminal conspiracy is a well-settled and codified law, as has been discussed

above. After this brief overview of criminal conspiracy, now this paper will focus on the tort of

conspiracy.

TORT OF CONSPIRACY

In the classic case of Quinn v. Leathem8, the tort of conspiracy was famously defined as, “A

conspiracy is an unlawful combination of two or more persons to do that which is contrary to

law, or to do that which is wrongful and harmful towards another person, or to carry out an

object not in itself unlawful but by unlawful means.” In simple words, when two or more people

come together to cause harm to some other person, and do some act in furtherance of their

intention and such act actually causes harm to that person, then the tort of conspiracy is said to

be completed. Conspiracy can also be understood in terms of partnership, where a group of

people come together under an agreement to form a partnership in which each member becomes

the partner or agent to each member and agrees to commit or to engage in planning of some act.

It is immaterial whether the conspirators are in combination at every stage of conspiracy or not.

The tort of conspiracy is also known as civil conspiracy.

8

(1901) AC 495 (528).

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

A conspiracy to injure differs widely from an invasion of civil rights by a single individual

because a number of things not in themselves unlawful if done separately, may with conspiracy

become dangerous and alarming.

Though the early law of Britain knew a writ of conspiracy, it was restricted to abuse of legal

procedure and the legal action in the nature of conspiracy, which came into fashion in the reign

of Elizabeth I, has now developed into the modern tort of malicious prosecution. Conspiracy as a

crime was developed in Britain by the Star Chamber during the 17th century and, when taken

over by the common law courts came to be regarded as not only a crime, but also as capable of

giving rise to civil liability, provided damage resulted to the claimant. 9 As a tort, however, it was

little developed until the second half of the 19th century10 and the law remained obscure until the

decision of the House of Lords in Crofter Hand Woven Harris Tweed Co Ltd v Veitch11.

Conspiracy remains a crime as well as a tort, but the scope of criminal conspiracy has been

curtailed by the statute of Criminal Law Act 1977. The only conspiracies that are now indictable

as criminal are those to commit a substantive criminal offence, to defraud, or to corrupt public

morals or outrage public decency. However, civil conspiracy is not restricted by any statute and

has a wider scope. Any conspiracy that fulfills the essential elements of civil conspiracy may

incur civil liabilities.

In India, on the other hand, criminal conspiracy is governed by Sections 120A and 120B of the

IPC, while the tort of conspiracy remains uncodified and thus, guided by the principles of

common law, the principle of justice, equity and good conscience, and the precedents. The tort of

conspiracy in India has been adopted from that in Britain.

9

WINFIELD & JOLOWICZ, TORT (18th ed. 2010)

10

Midland Bank Trust Co. Ltd. v. Green (No. 3) [1982] Ch. 529 at 539.

11

[1942] A.C. 435.

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

ESSENTIALS OF THE TORT OF CONSPIRACY:

The following are the essential elements of the tort of conspiracy:

1. INTENTION:

A common intention to harm or injure another is the first essential of the tort of conspiracy. For a

tort to become a conspiracy, there must be a common intention to harm the other person. If the

real purpose of the combination is not to injure another, but to forward or defend the trade of

those who enter into it, then no wrong is committed and no action will lie although damage to

another ensues. The degree of intention to harm may vary, but its presence is of utmost

importance.

The object or purpose of the combination must be to cause damage to the claimant. The aim of

this test is to know what was there in the mind of the combiners when they acted as they did.

Combiners should have acted in order that the claimant should suffer damage. If they did not act

in order that the claimant should suffer damage but to pursue their own advantage, they are not

liable, however selfish their attitude and however inevitable the claimant‟s damage may have

been.

Although malevolence is not necessary, where that state of mind is what motivates the

defendants they may be liable even though precisely the same acts would be lawful in pursuit of

their interests.

Individuals rarely act from a single motive but in these cases the question must be asked what

was the predominant purpose of the combination, and if the main motive was the pursuit of the

defendant‟s interests, then their conduct is not actionable even if they were also pleased by the

claimant‟s loss.

Thus, to bring any act under the purview of the tort of conspiracy, the first question would be

regarding the intention of the defendants, and if the requisite intention cannot be proved, then the

whole case of the claimant will fail.

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

2. COMBINATION:

The second essential element of the tort of conspiracy is „combination‟, which means that at least

two or more persons must combine together, and there must be concerted action between them.

The obvious reason why at least two persons are needed is that no one can conspire with himself,

which was elaborately discussed in the case of Topan Das v. State of Orissa12. There must be

voluntary agreement and intent to participate in furthering a common purpose so as to make a

person liable under conspiracy. But mere knowledge or approval, in the absence of an actual

agreement does not constitute conspiracy. Also, two separate entities working separately would

not give rise to the tort of conspiracy, even if they have the same intention. It is absolutely

essential that they must have combined together, and be working together towards a common

intention. Merely having same intention, but without any combination is not enough to result into

the tort of conspiracy. For instance, if a Mr. A, with the intention to assault Mr. X, enters upon

his land, and Mr. B, also with the intention to assault Mr. X enters his land, then this does not

give rise to conspiracy, as Mr. A and Mr. B had not combined together, though they had the

same intention. But, if Mr. A and Mr. B had come to an agreement that Mr. A will assault Mr. X

while Mr. B will keep guard at the door, with the common intention of assaulting Mr. X, then the

element of „combination‟ is complete, and this will give rise to conspiracy.

The conspirators under the tort of conspiracy can also be husband and wife.13 Under common

law principle, husband and wife are considered as a single entity, but under civil conspiracy, they

are considered as two and can be charged with conspiracy.

There can be no conspiracy between an employer and his employees, at least where they merely

go about their employer‟s business.14 This means that an employer and his employees cannot be

considered to be co-conspirators, if the employees were simply doing their employer‟s bidding.

This is a safeguard against the employees being liable for conspiracy in cases where they were

simply following their employer‟s orders.

12

AIR 1956 SC 33.

13

Midland Bank Trust Co. Ltd. v. Green (No. 3) [1982] Ch. 529.

14

CLERK & LINDSELL, TORTS (19thed. 2006).

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

3. OVERT ACT:

There must be some overt act done, which caused harm or damages to the other person. Then

only it can be considered as a civil conspiracy. It is not necessary that the whole conspiracy must

have been carried out and completed for the completion of this element of the tort of conspiracy.

It is only essential that some act towards the fulfillment of the intention of the conspirators must

have been done, and that such act must have caused some damage to the claimant.

An overt act is not merely an evidence of conspiracy; it must be something more than that. For

the element of „overt act‟ to be said to be complete, it is necessary that one of the conspirators

must have carried out an act for the fulfillment of the intention behind the conspiracy and

towards the execution of the conspiracy. An overt act is an act that is done to fulfill the objective

of the conspiracy. Before the tort of conspiracy can be said to be complete, some overt act must

have been accomplished by any one of the conspirators.

Overt act that causes damage to the claimant is an essential element of liability in torts. If,

therefore, the acts relied on are incapable of being made part of any cause of action- for example

evidence given by witnesses in a court of law- then the tort cannot be made out.15 A sufficient

element of damage has to be shown, where expenses were necessarily incurred by the claimant in

investigating and counteracting the machinations of the defendants.16 Though the claimant is

required to prove some actual pecuniary loss, once that is done damages are not limited to the

amount so proved. 17

15

Marrinan v. Vibart [1963] 1 Q.B. 234.

16

B.M.T.A. v. Salvadori [1949] Ch. 556.

17

Lonrho Plc v. Fayed (No. 5) [1993] 1 W.L.R. 1489.

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

TYPES OF THE TORT OF CONSPIRACY:

There are two types of civil conspiracy:

Conspiracy to Injure- “Crofter” Conspiracy

“Unlawful means” Conspiracy

CONSPIRACY TO INJURE- “CROFTER” CONSPIRACY:

It was firmly established in Crofter Hand Woven Harris Tweed Co Ltd v Veitch18 that if there is a

combination of persons whose purpose is to cause damage to the claimant, that purpose may

render unlawful acts which would otherwise be lawful and which would be lawful if committed

by one person even with the purpose of causing injury. In this type of conspiracy, the pre-

dominant purpose of the combination is to injure the other party. The Lordships made it clear

that if the predominant purpose of a combination is to injure another in his trade or business or in

his other legitimate interests then, if damage results, the tort of conspiracy exists.

The test is not what the defendants contemplated as likely or even as an inevitable consequence

of their conduct, it is, “what is in truth the object in the minds of the combiners when they acted

as they did?” Malice in the sense of malevolence, spite or ill will is not essential for liability, nor

is it sufficient if merely superadded to a legitimate purpose; what is required is that the

combiners should have acted in order that (not with the result that, even the forseeably inevitable

result) the claimant should suffer damage. If they acted to pursue their own advantage, they are

not liable under this, however selfish their attitude and however inevitable the claimant‟s damage

may have been.

A combination that results in injury to another, without the use of unlawful means is not

actionable, where it is designed to pursue the “legitimate” or “lawful” interests of the defendants.

Thus Viscount Simon said that if the: “Predominant purpose is to damage another person and

damage results, that is tortious conspiracy. If the predominant purpose is the lawful protection or

promotion of any lawful interest of the combiners (no illegal means being employed), it is not a

18

[1942] A.C. 435.

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

tortious conspiracy, even though it causes damage to another person.” Therefore there is no

actionable conspiracy where the defendants act to improve their share of the market at the

claimant‟s expense19 or to strengthen the position of a trade union or its members or to maintain

prices in the trade to the common benefit of the members20.

“UNLAWFUL MEANS” CONSPIRACY:

This tort involves an arrangement between two or more parties, whereby they agree that at least

one of them will use unlawful means against the claimant, and, although damage to the claimant

need not be the predominant intention of any of the parties, the claimant must have suffered loss

or damage as a result.

There are two elements of this type of conspiracy-

a) Intention of the defendant- This form does not require a predominant purpose to injure the

claimant. However, the tort still requires an intention to injure; it is not enough that the

defendants combine to do an unlawful act which has the effect of causing damage to the

claimant. If the damage to the claimant is not an end in itself, it must at least be a necessary

means to some other end and it is not enough that it is a forseeable consequence of the

unlawful means used. The damage to the claimant must be an essential stepping stone to

achieve the end, or to fulfill the motive for which the conspiracy was made.

b) Unlawful means- Unlawful means are acts or threats of acts which are or would be civilly

wrongful and actionable (or would be actionable if loss was suffered), or acts that are

criminal but which would not be civilly actionable if done by one person.

If the above mentioned two elements are fulfilled, then the defendants are proven to be liable for

“unlawful-means conspiracy‟.

19

Mogul S.S. Co. Ltd. v. McGregor Gow & Co., [1892] A.C. 25.

20

Ware and de Freville Ltd. v. Motor Trade Association, [1921] 3 K.B. 40.

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

COMPARATIVE ANALYSIS OF CONSPIRACY AS CRIME AND AS TORT

There are three points of difference between criminal conspiracy and tort conspiracy. The first is

based on the presence of an overt act, the second is based on conspiracy between husband and

wife, and the third is about restrictions.

OVERT ACT:

According to civil conspiracy, presence of an overt act that also causes damage to the claimant is

very important. There must be some harm inflicting action taken by at least one of the

conspirators, to be liable under the tort of conspiracy. Whereas, in criminal conspiracy, no overt

act is required.21 In criminal conspiracy, agreement and meeting of minds are the only essentials.

It is the intention to commit crime, joining hands with persons having the same intention and

agreement to carry out the object of the intention, which is an offence and is punishable under

criminal conspiracy. In a case where the agreement is for accomplishment of an act which by

itself constitutes an offence, then in that event, unless the Statute so requires, no overt act is

necessary to be proved by the prosecution because in such a fact situation criminal conspiracy is

established by proving such an agreement.22 When two persons agree to carry it into effect, the

very plot is an act in itself, and an act of each parties, promise against promise, actus contra

actum, capable of being enforced, if lawful, punishable if for a criminal object or for use of

criminal means.23 Thus, in civil conspiracy, overt act causing damage is important, but in

criminal conspiracy, agreement is the gist of the offence.

CONSPIRACY BETWEEN HUSBAND AND WIFE:

In civil conspiracy, husband and wife are considered as separate entities and they can be held

liable under the tort. But, under criminal conspiracy, they are considered as one and cannot be

held liable.

21

K. Hasim v. State of T.N., AIR 2005 SC 128.

22

Sushil Suri v. C.B.I, AIR 2011 SC 1713.

23

Chaman Lal v. State of Punjab, AIR 2009 SC 2972.

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

RESTRICTIONS:

Criminal conspiracy is codified under a statute and, so there are restrictions on which acts can be

considered as conspiracy and which not. There are only a few specified acts that are liable under

criminal conspiracy, such as those to commit a substantive criminal offence, to defraud, or to

corrupt public morals or outrage public decency. But, there are no such restrictions on civil

conspiracy, since it is not codified. Any act that fulfills the essentials of the tort of conspiracy

can be made liable under it.

CASE LAWS IN TORT OF CONSPIRACY

1. Mogul Steamship Co. v. McGregor Gow and Co24:

The defendants, who were firms of ship owners were trading between China and Europe, with a

view to obtaining for themselves a monopoly of the homeward tea trade, and thereby keeping up

the rate of freight. They formed an association, and offered the merchants and shippers in China

who shipped their tea exclusively in vessels belonging to the members of the association, a

rebate of five percent. The plaintiffs, who were rival ship owners, were excluded by the

defendants from all the benefits of the association, and in consequence of such exclusion, they

sustained damage. The plaintiffs filed a suit against the defendants, alleging conspiracy to injure.

It was held that the acts of the defendants were done with the lawful object of protecting and

extending their trade and increasing their profits, and since they had not employed any unlawful

means, they were held not liable and the plaintiffs had no cause of action.

2. Sorrel v. Smith25 :

The plaintiff, who was a retail newsagent, used to take his newspaper from „R‟. He withdrew his

custom from „R‟, and started taking newspaper from „W‟. The defendants, who were the

members of a committee of circulation managers of London Daily papers, threatened to cut off

the newspaper supply to „W‟, if he continued to supply newspapers to the plaintiff. The plaintiff

filed an action against the committee. The defendants were held not liable, since they had acted

24

[1892] AC 25.

25

[1925] AC 700.

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

in this way to promote their own business interests. Their main object was not to injure the retail

newsagent i.e. the plaintiff, and so, they couldn‟t be held liable.

3. Crofter Hand Woven Harris Tweed Co. Ltd. v. Veitch26:

In this case, the trade union, that is the defendant, directed the dockers, who were also the

members of the union to refuse to handle the plaintiff‟s goods, without any breach of contract.

The object of this act was to reduce the competition in the yarn trade market, thereby increasing

profit and thus increasing the wages of the members of the union working in the mills. The

predominant purpose of the defendants‟ act was to improve the economic prospects of its

members in the mills. Their actions were not motivated by any intention to injure the plaintiff,

nor were there any unlawful means involved, and thus they were held not liable.

4. Hunteley v. Thornton27:

There was a call for strike by a workers‟ union. The plaintiff, a member of the union, refused to

comply with the union‟s call for strike. The defendants, the secretary and some members of the

union, wanted the expulsion of the plaintiff from the union, but the executive council of the

union decided not to do that. The defendants then, out of spite against the plaintiff, made sure

that he remained out of work. In this case, the acts of the defendants were predominantly

intended to injure the plaintiff because of their grudge. The defendants were held liable and the

plaintiff was entitled to recover damages.

5. Rohtas Industries Ltd. v. Rohtas Industries Staff Union28:

The workmen of two industrial establishments went on strike. The strike was illegal under

Section 23 read with Section 24 of the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947, as conciliation proceedings

were pending. The question before the Supreme Court was whether the union was liable to pay

compensation to the management for the loss incurred by it. Since the strike was illegal, it was

also unlawful, but it was held that the union was not liable because their object was not to cause

injury to the management. Their only purpose was to benefit themselves and thus they were held

not liable.

26

[1942] AC 435.

27

[1957] 1 W.L.R. 321.

28

(1976) 2 SCC 82.

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

6. Pepsi Foods Ltd. and Others v. Bharat Coca-Cola Holdings Pvt. Ltd.29:

The plaintiffs were engaged in manufacturing, marketing and sale of soft drinks and beverages,

under the trade mark „Pepsi‟ all over the world, including India. Over the past 6 months the

plaintiffs found that the defendants had been resorting not only to unethical business practices,

but the defendants‟ actions in most cases constituted tortious interference in the business of the

plaintiffs. It was further mentioned that the defendants had entered into conspiracy to undertake

concerted action against the plaintiffs to damage their business interests in an illegal manner. It

was alleged that the defendants are guilty of the tort of conspiracy. On consideration of the

totality of the facts and circumstances, the plaintiffs were not able to make out a strong prima

facie case for the grant of injunction at that stage. The balance of convenience was also not in

favour of the plaintiffs. No irreparable injury was likely to be caused to the plaintiffs. Also, since

the third essential of conspiracy, i.e. overt act that causes damage to the claimant, was not

fulfilled, the case was not actionable.

7. Revenue and Customs Commissioners v. Total Network SL30:

A person „A‟ in country „X‟ contracted to sell goods to „B‟ in country „Y‟. „B‟ then sold the

goods to „C‟ and „C‟ paid VAT for it. „B‟ then disappeared without paying revenue for the VAT

earned by him and „C‟ resold the goods to „A‟ and reclaimed his VAT before the Revenue

discovered the disappearance of „B‟. In this case, conspiracy to injure could not be proved,

because the predominant purpose of the combiners was not to injure, but to gain profit. But, the

unlawful means conspiracy was applicable here and they were held liable for the tort of

conspiracy of the nature of unlawful means conspiracy.

29

1999 ILR Del 193.

30

(2008) 2 All ER (HL).

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

CONCLUSION

The concept of law of torts developed in India from England when it was under the colonial rule.

There are many difference between the law of torts of India and other countries, and some

features of torts are absent in India because of the vast difference in the cultures, societies and

systems. Torts conspiracy needs more development in India because in Indian system, tort law is

totally uncodified and punishment for crimes is given more importance than compensation for

wrongs.

A conspiracy is defined as an unlawful combination of two or more persons to do that which is

contrary to law, or to do that which is harmful towards another person, or to carry out an object

not in itself unlawful, but by unlawful means. Some acts that are important for a conspiracy to

become complete, are not unlawful in themselves or do not make the person liable, but, under the

tort of conspiracy, even such a person can be made liable for this act. This person, who has

committed the act for the furtherance of the conspiracy, is made liable under the tort of

conspiracy, only because there was a combination of people who had a common intention that

was contrary to law. Thus, this becomes the objective of the tort of conspiracy, to make everyone

who has done anything harmful to another pay for it.

The only problem with the tort of conspiracy, in my view, is that it does not make an individual

liable. If, in a case of conspiracy, there are three conspirators, and if the case does not stand

against two of them, then the third person can also not be tried under conspiracy. This might

leave the aggrieved party without any compensation, even though there was wrong done against

him.

Also, collection of evidence in conspiracy cases is very important in order to ensure that there is

sufficient proof to support all of the required elements of the cause of action, particularly

regarding the intention to act in concert or, in other words, the common intention of the

conspirators.

There is also a risk of claims being made in conspiracy, where a business is carried on, or a

transaction made, in the knowledge that financial loss thereby will be inflicted upon a

competitor, where there is some illegality involved, either under criminal or tort law. To what

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

extent must subjective knowledge be shown of such illegality? If a person knows all the facts

showing unlawful means but he does not realize the means are unlawful, is this sufficient for the

tort of conspiracy? This is a difficult question on which there are different dicta. Those who

deliberately breach the law, tort or criminal, in commercial activity may find themselves being

sued in economic tort for substantial sums, by competitors, where there is some nexus between

the illegal means and loss caused.

Therefore, tort conspiracy in India requires many reforms and enactments to make it more

ascertainable.

Published in Articles section of www.manupatra.com

You might also like

- Simple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaFrom EverandSimple Guide for Drafting of Civil Suits in IndiaRating: 4.5 out of 5 stars4.5/5 (4)

- Project On The Constituent Elements of Crime in The Indian Penal CodeDocument18 pagesProject On The Constituent Elements of Crime in The Indian Penal CodeAsha Yadav100% (1)

- Law On Obligations and ContractsDocument308 pagesLaw On Obligations and ContractsDenisse Meneses100% (6)

- DIGEST Rule 2 No. 3 Soloil v. Philippine Coconut AuthorityDocument4 pagesDIGEST Rule 2 No. 3 Soloil v. Philippine Coconut AuthorityRomnick Jesalva100% (2)

- Bell V Lever Brothers LTD Case NotesDocument8 pagesBell V Lever Brothers LTD Case NotesHarleen Napier100% (1)

- Tort of Conspiracy: AbstractDocument22 pagesTort of Conspiracy: AbstractVyas NikhilNo ratings yet

- Law of Torts Unit-I NotesDocument40 pagesLaw of Torts Unit-I NotesBgmi PlayNo ratings yet

- Ipc Final ProjectDocument17 pagesIpc Final ProjectShubhankar Thakur100% (1)

- General Principles of Criminal Law and IpcDocument12 pagesGeneral Principles of Criminal Law and IpcR Raman ChandraNo ratings yet

- Project On Criminal ConspiracyDocument17 pagesProject On Criminal ConspiracyShubhankar ThakurNo ratings yet

- Objectives: The Proposed Research Paper Aims To Achieve The Following ObjectivesDocument23 pagesObjectives: The Proposed Research Paper Aims To Achieve The Following ObjectivesGuddu SinghNo ratings yet

- TortsDocument471 pagesTortsvishnu000No ratings yet

- Law of Torts Notes (Mahima)Document145 pagesLaw of Torts Notes (Mahima)charuarora153No ratings yet

- Economic Duress - A Judicial StudyDocument15 pagesEconomic Duress - A Judicial StudyARJU JAMBHULKARNo ratings yet

- Criminal Law Notes-1-1-1Document177 pagesCriminal Law Notes-1-1-1DATIUS DIDACE(Amicus Curiae)⚖️91% (22)

- Law of TortsDocument15 pagesLaw of TortsAnand Yadav100% (1)

- 18163-Shawaiz Project (CRL) PDFDocument15 pages18163-Shawaiz Project (CRL) PDFshawaiz nisarNo ratings yet

- The Law of Torts in IndiaDocument6 pagesThe Law of Torts in Indiaajay csNo ratings yet

- Notes On Law of Torts - 221008 - 165334Document33 pagesNotes On Law of Torts - 221008 - 165334keerthichallagallaNo ratings yet

- Constructive Joint LiabilityDocument20 pagesConstructive Joint LiabilityArnav50% (2)

- Compensation To The Victim of Crime - Assessing Legislative Frame Work and Role of Indian CourtsDocument5 pagesCompensation To The Victim of Crime - Assessing Legislative Frame Work and Role of Indian CourtsANo ratings yet

- Torts ProjectDocument18 pagesTorts ProjectAshhab KhanNo ratings yet

- Tort AssignmentDocument5 pagesTort AssignmentProsfutita SinghaNo ratings yet

- WWW - Defactolaw.In: Website Blog Dedicated To Upsc Law OptionalDocument20 pagesWWW - Defactolaw.In: Website Blog Dedicated To Upsc Law OptionalAyush PandeyNo ratings yet

- WWW - Defactolaw.In: Website Dedicated To Upsc Law OptionalDocument21 pagesWWW - Defactolaw.In: Website Dedicated To Upsc Law Optionalaarti sharmaNo ratings yet

- Chapter-1: Criminal Conspiracy in IndiaDocument16 pagesChapter-1: Criminal Conspiracy in IndiaSomiyo HoramNo ratings yet

- Stages of CrimeDocument19 pagesStages of CrimeKunaal SaxenaNo ratings yet

- Summary Egineering Law Get 511 - 101154Document8 pagesSummary Egineering Law Get 511 - 101154Micheal RobertNo ratings yet

- Ipc 3Document15 pagesIpc 3DhwajaNo ratings yet

- Introduction To Law and Fundamental RightsDocument55 pagesIntroduction To Law and Fundamental Rightsrita tamohNo ratings yet

- 19213-Cr PCDocument22 pages19213-Cr PCadvocatekishanrhc1993No ratings yet

- 2019BALLB131 - Semester 3 - Law of CrimesDocument19 pages2019BALLB131 - Semester 3 - Law of CrimesTanishka SaxenaNo ratings yet

- 2022 - 01 - Introudction To The Legal SystemDocument18 pages2022 - 01 - Introudction To The Legal SystemAwais FarooqNo ratings yet

- Misfeasance PDFDocument17 pagesMisfeasance PDFsahilsingh20022000No ratings yet

- Indian Penal CodeDocument25 pagesIndian Penal Codeanupathi mamatha deen dayalNo ratings yet

- Mens Rea in Statutory OffencesDocument10 pagesMens Rea in Statutory OffencesDheeresh Kumar DwivediNo ratings yet

- 6 The Elements of Crime Under The PakistaniDocument13 pages6 The Elements of Crime Under The PakistaniFaiza ChandioNo ratings yet

- CRPC TanayaDocument17 pagesCRPC TanayaAbhishek PratapNo ratings yet

- Revised By: Atty. Virginio L. ValleDocument308 pagesRevised By: Atty. Virginio L. Vallebv123bv100% (9)

- Criminal Law Vs Civil LawDocument26 pagesCriminal Law Vs Civil Lawsrikant100% (3)

- Karat Lawz Academy Indian Penal Code, 1860Document15 pagesKarat Lawz Academy Indian Penal Code, 1860Shimpy TiwariNo ratings yet

- Doctrine of Mens Rea Under Indian Penal CodeDocument9 pagesDoctrine of Mens Rea Under Indian Penal CodedeepakNo ratings yet

- Criminal LawDocument5 pagesCriminal LawArushi JhaNo ratings yet

- Mens Rea in Statutory OffencesDocument10 pagesMens Rea in Statutory OffencesVardhaman PandeyNo ratings yet

- Law of Crimes. P1Document36 pagesLaw of Crimes. P1Harmeet KaurNo ratings yet

- 09 - Chapter 4Document127 pages09 - Chapter 4ShivarajNo ratings yet

- The Legal Effect of The International Bill of Human Rights in The PhilippinesDocument28 pagesThe Legal Effect of The International Bill of Human Rights in The PhilippinesPaolo VariasNo ratings yet

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights As Part of Customary International LawDocument70 pagesUniversal Declaration of Human Rights As Part of Customary International LawJahirulNo ratings yet

- Common Intention Versu'S Common ObjectDocument19 pagesCommon Intention Versu'S Common ObjectSaurabh Kumar SinghNo ratings yet

- Study of Tort (1) PDF 3Document140 pagesStudy of Tort (1) PDF 3ashishNo ratings yet

- Nature and Scope of Law of Torts - Author - Lakshmi SomanathanDocument5 pagesNature and Scope of Law of Torts - Author - Lakshmi SomanathanJasmine Singh100% (1)

- 08 July 2023 CA Analysis - Hinglish - Priti Saxena PDFDocument9 pages08 July 2023 CA Analysis - Hinglish - Priti Saxena PDFz5nsrntkydNo ratings yet

- Obligations PowerpointDocument206 pagesObligations PowerpointJamesAnthonyNo ratings yet

- Contracts 2Document15 pagesContracts 2Konark SinghNo ratings yet

- TortDocument17 pagesTortAniket KolapateNo ratings yet

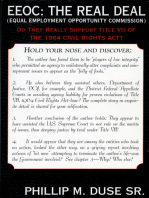

- EEOC: The Real Deal - Do They Really Support Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act?From EverandEEOC: The Real Deal - Do They Really Support Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act?No ratings yet

- Bar Review Companion: Remedial Law: Anvil Law Books Series, #2From EverandBar Review Companion: Remedial Law: Anvil Law Books Series, #2Rating: 3 out of 5 stars3/5 (2)

- Constitutional Law Project 3rd TriDocument21 pagesConstitutional Law Project 3rd TriRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Patent LawDocument8 pagesPatent LawRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Specific Goods in A Deliverable State (Sec.20)Document10 pagesSpecific Goods in A Deliverable State (Sec.20)Radha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Surrogacy Law in India: Vinay KumarDocument15 pagesSurrogacy Law in India: Vinay KumarRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Religion and SocietyDocument1 pageReligion and SocietyRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Public Interest LitigationDocument3 pagesPublic Interest LitigationRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Relation Between Adminstrative Law and Constitutional LawDocument18 pagesRelation Between Adminstrative Law and Constitutional LawRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Theory of ConstitutionalismDocument15 pagesTheory of ConstitutionalismRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- National Law Institute University BhopalDocument7 pagesNational Law Institute University BhopalRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Sociology of Law ProjectDocument16 pagesSociology of Law ProjectRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- National Law Institute University BhopalDocument23 pagesNational Law Institute University BhopalRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Sociology of Law ProjectDocument15 pagesSociology of Law ProjectRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Law of Industrial AccidentsDocument10 pagesLaw of Industrial AccidentsRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Sociology of Law ProjectDocument15 pagesSociology of Law ProjectRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Between Black and NonetDocument7 pagesBetween Black and NonetRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Securing The Independence of The Judiciary PDFDocument4 pagesSecuring The Independence of The Judiciary PDFRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Theory of ConstitutionalismDocument15 pagesTheory of ConstitutionalismRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Fundamentals of Presidential Form of GovernmentDocument15 pagesFundamentals of Presidential Form of GovernmentRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Legislature: Political Science I III Trimester Feb To April 2020Document23 pagesLegislature: Political Science I III Trimester Feb To April 2020Radha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Law, Society and Industrial Justice (Autosaved)Document11 pagesLaw, Society and Industrial Justice (Autosaved)Radha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Dsoc102 Social Institutions EnglishDocument180 pagesDsoc102 Social Institutions EnglishRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- For Jurisprudential SociologyDocument6 pagesFor Jurisprudential SociologyRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- Boundaries of Legal SociologyDocument8 pagesBoundaries of Legal SociologyRadha CharpotaNo ratings yet

- HR Case Digest RA 9262Document7 pagesHR Case Digest RA 9262Amiel Lyndon PeliasNo ratings yet

- Professional ResponsibilityDocument27 pagesProfessional ResponsibilityStacy OliveiraNo ratings yet

- Charles Richey v. Leroy Cartledge, 4th Cir. (2016)Document21 pagesCharles Richey v. Leroy Cartledge, 4th Cir. (2016)Scribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- CA - Navarro vs. CornejoDocument26 pagesCA - Navarro vs. CornejoTricia Rosario100% (1)

- Crim 2 - FinalsDocument3 pagesCrim 2 - FinalsMaria Lorna O BerionesNo ratings yet

- 8-26-16 Police ReportDocument14 pages8-26-16 Police ReportNoah StubbsNo ratings yet

- Bueckert Factum For Anti-SLAPP Motion - Nov 12, 2019Document34 pagesBueckert Factum For Anti-SLAPP Motion - Nov 12, 2019Michael Bueckert100% (1)

- Charles Taylor Sentencing TranscriptDocument19 pagesCharles Taylor Sentencing TranscriptimpunitywatchNo ratings yet

- 22.republic v. Hernandez - DigestDocument3 pages22.republic v. Hernandez - DigestIa Dulce F. AtianNo ratings yet

- In The Supreme Court of The United States United States V. Dotterweich 320 U.S. 277, 64 S.Ct. 134 (Case Analysis)Document7 pagesIn The Supreme Court of The United States United States V. Dotterweich 320 U.S. 277, 64 S.Ct. 134 (Case Analysis)Aqib khanNo ratings yet

- !camp Arifjans Corruption Indicted and ConvictedDocument58 pages!camp Arifjans Corruption Indicted and ConvictedTrafficked_by_ITT100% (1)

- Crim Pro 117-118Document10 pagesCrim Pro 117-118JP TolNo ratings yet

- McDonalds Coffee CaseDocument1 pageMcDonalds Coffee Casejuzzy52No ratings yet

- Alberto vs. de La Cruz, 98 SCRA 406Document3 pagesAlberto vs. de La Cruz, 98 SCRA 406jin2chingNo ratings yet

- Mckee Vs IACDocument2 pagesMckee Vs IACEllen Glae Daquipil100% (2)

- Tennessee Senator Calls For Investigation Into Shelby Co. DA, JudgeDocument4 pagesTennessee Senator Calls For Investigation Into Shelby Co. DA, JudgeLydian CoombsNo ratings yet

- 100-Valeriano vs. ECCDocument6 pages100-Valeriano vs. ECCNimpa PichayNo ratings yet

- CRLP3918 15 26 08 2015Document6 pagesCRLP3918 15 26 08 2015naveen KumarNo ratings yet

- The Homicide Courts of Ancient AthensDocument44 pagesThe Homicide Courts of Ancient AthensdedelamenaceNo ratings yet

- 11.09.13AM Family Code (Atty. Raymond B. Batu)Document18 pages11.09.13AM Family Code (Atty. Raymond B. Batu)Miggy Zurita100% (1)

- YouGotPosted / Ugotposted Contempt OrderDocument7 pagesYouGotPosted / Ugotposted Contempt OrderAdam Steinbaugh100% (1)

- Abhishek Verma CaseDocument3 pagesAbhishek Verma CaseNitika NagarNo ratings yet

- Pre-Trial PamaDocument5 pagesPre-Trial PamaAlijoh Aries M. AquidadoNo ratings yet

- People V Lava Et AlDocument2 pagesPeople V Lava Et AlJonBelza100% (2)

- G.R. No. 160239Document13 pagesG.R. No. 160239alain_kris0% (1)

- United States Court of Appeals: Corrected Opinion PublishedDocument41 pagesUnited States Court of Appeals: Corrected Opinion PublishedScribd Government DocsNo ratings yet

- Human Rights Law CasesDocument343 pagesHuman Rights Law CasesDia Mia BondiNo ratings yet

- OjsimpsonhomeworkdiscussionrDocument2 pagesOjsimpsonhomeworkdiscussionrapi-400760060100% (1)