Copenhagen Business School Law: Research Paper Series No. 20-16

Copenhagen Business School Law: Research Paper Series No. 20-16

Uploaded by

RazzaqeeeCopyright:

Available Formats

Copenhagen Business School Law: Research Paper Series No. 20-16

Copenhagen Business School Law: Research Paper Series No. 20-16

Uploaded by

RazzaqeeeOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Copenhagen Business School Law: Research Paper Series No. 20-16

Copenhagen Business School Law: Research Paper Series No. 20-16

Uploaded by

RazzaqeeeCopyright:

Available Formats

Copenhagen Business School

Law Research Paper Series No.

20-16

Special issue I:

International Tax Challenges

for Developing Countries

Less is More

- Can Developing Countries Gain Tax

Revenue by Giving up Taxing Rights?

Jeroen Lammers

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

LESS IS MORE

CAN DEVELOPING COUNTRIES GAIN TAX REVENUE BY GIVING UP TAXING RIGHTS?

7 August 2020

Updated version of https://ssrn.com/abstract=3630466

Jeroen Lammers

External PhD candidate University of Amsterdam and Copenhagen Business School

ABSTRACT

The international debate on tax avoidance lately is focused on digital business models. In the

G20/OECD Inclusive Framework on BEPS 137 countries are currently developing the so-called Unified

Approach to address the tax challenges arising from the digitalization of the economy. The aim of

this paper is to examine the possible effects of the separate elements of the Unified Approach on tax

revenue and investment levels for developing countries. The findings show that all the proposals are

highly technical and would require much in terms of capacity of developing countries. Moreover, the

extra tax revenue for developing countries is rather modest, certainly from some of the more

complex proposals. This paper therefore suggests a number of alternate policy options to

significantly reduce complexity, while ensuring developing countries gain the same or more in extra

tax revenue. Moreover, one suggested alternative could effectively reduce harmful tax competition

and prevent future tax disputes.

1. Introduction

The OECD has been working on addressing the tax challenges arising from the digitalization of the

economy for some time. The OECD has identified that the current international tax rules allow for

(primarily) digital business models to provide services to clients in market jurisdiction without having

to pay any profit tax in those jurisdictions 1. And, thus, that the current international tax rules lead to

a situation where certain business models are not subject to appropriate levels of taxation in each

jurisdiction in which they are active (OECD 2019b, para 28).

The OECD has developed the Unified Approach to address this issue. This approach consists of a

number of proposals that aim to fulfil overall key objectives, such as:

Give market jurisdictions access to significantly more tax revenue

Ensure that digital companies are adequately taxed

Ensure that multinational corporations cannot avoid appropriate levels of taxation by

moving activities to jurisdictions with very low tax rates

Restore the level playing field between internationally and locally operating companies

Provide greater tax certainty

1The current rules require some kind of physical presence in a jurisdiction in order for that jurisdiction to have the right to

tax profits.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

2

The OECD has released a number of documents outlining these proposals, put out two public

consultations to invite comments on the approach and has hosted a number of public consultation

meetings and webcasts as the proposals are developed further. There has been a lot of public

interests in these proposals. This is attested by the fact that thousands of pages of commentary have

been received by the OECD on the public consultations, as well as that many commentators have

written about these proposals in scientific journals, mainstream media and social media.

Remarkably, however, there are very few, commentators among these that have asked a very

fundamental question: do these proposals actually deliver on the stated key objectives? Instead

most of these commentators focused on the technical (legal) details of the proposals, whether or

not they could be applied in practice, if it would lead to double taxation and/or increased

uncertainty etc. All very relevant issues, but perhaps rather moot points should the proposals fail to

deliver on their very raison d’être.

Recently I have argued that at least Amount A, arguably the most radical and without a doubt the

most discussed proposal of the Unified Approach, does not give market jurisdictions access to

significantly more tax revenue (Lammers 2020). This paper intents to build on that research by

extending the analysis to all the separate proposals of the Unified Approach and, at the same time,

focusing on the effects of the Unified Approach for developing countries in particular. This paper

focuses on developing countries, because the corporate tax receipt is especially important to them

and they have arguably been affected most by corporate tax avoidance practices (UNCTAD 2015,

200). Besides, for the international tax system to function, also developing countries have to be able

to apply the (new) rules to determine where corporate profits should be taxed. And they already

have enough problems with the system as it is now and certainly do not need or have the capacity to

deal with additional complexities (Cooper et al 2017, 9).

One could argue that it is still very early to look at the effects of the proposals as the proposals are

not yet fully fleshed out. That it is more important at this stage to develop the legal framework and

work out the exact details and parameters of the proposals. However, IMF has recently warned that

policy decisions of the significance to the international tax system, such as the Unified Approach,

should not be made without any real understanding of the likely consequences (Beer et al 2020, 42).

Moreover, at this point it is very difficult to access the relevant data needed to really help to gain

insight in these likely consequences. So, to determine if the direction of travel is the right one, it is

very important to let the iterative development of the legal framework go hand in hand with the

improvement of understanding of its effects.

In this respect it is also relevant to note that the discussions on the Unified Approach in the

G20/OECD Inclusive Framework are affected by the Covid-19 pandemic. On the one hand, there is a

delay as discussions can only be held online and the originally planned G20/OECD Inclusive

Framework meeting in Berlin on 1-2 July (OECD no date a) cannot take place (OECD 2020c). On the

other hand, there is pressure to speed up the process as the possible extra tax revenue from the

Unified Approach could compensate for increased deficits due to the emergency Covid-19 measures

(Tax Policy Center 2020). As a result, all is now aimed at reaching a political decision at the

G20/OECD Inclusive Framework meeting in the beginning of October, before the G20 Finance

Minister’s meeting takes place on 15 and 16 October in Washington DC. The question is if this mad

dash to the finish line is in the best interest of developing countries. Not in the least, because

especially the developing countries will face huge challenges battling the Covid-19 outbreak with

very limited resources (UNCTAD 2020, 5-6).

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

3

2. Aim, research approach and key findings

The aim of this paper is to examine what the societal impact of the OECD Unified Approach to

address the tax challenges of the digitalization of the economy could be for developing countries, in

particular the effects on tax revenue and investments levels. To this end, the possible effects on tax

revenue for developing countries of the proposals of the Unified Approach are examined 2, both

separately and in connection to each other. This analysis should help to provide insight in the

question if the Unified Approach is indeed the best policy solution for developing countries in

relation to the overall objectives, or that other avenues to get more (tax) revenue might be much

more advantageous to developing countries.

In exploring these other avenues, profit taxation does not necessarily need to be the only answer for

developing countries for more revenue. Even though the corporate income tax receipt is an

important source of income for developing countries other revenue sources 3 should not be

overlooked. For instance, one could argue that developing countries are cheated out of about 300

billion USD every year because of two reasons.

One is that foreign direct investors avoid an estimated 100 billion USD in profit taxation by diverting

their investments through offshore investment hubs (UNCTAD 2015, 200). 4 The other reason is that

advanced economies have failed to honour their commitments regarding development aid.

Advanced economies have promised as far back as 1972 to offer 0.7% of their GNI in Official

Development Assistance (ODA) by 2015 (UN no date a). In 2019 only 6 advances economies have

actually realised this goal (OECD no date b). The total shortfall in 2019 of all 45 advanced economies

together amounts to 191 billion USD (UN no date b).

2.1. Research Approach

As pointed out above, this paper does not mean to test the legal framework of the Unified

Approach, but rather it attempts to chart its effects. The reason for this perspective is that these

effects are really rather underexposed in the current policy debate, while they arguably are

instrumental for getting the proposed changes to international tax policy right.

To make a proper assessment of the societal impact of the OECD proposals access to sufficient and

reliable data is necessary. However, the relevant quantitative data is very often not publicly

available. This is in part due to the fact that the policy discussions on the exact parameters of the

proposals are still ongoing and in part because necessary firm-level data is often thought to be

proprietary in nature and therefore not readily accessible. Consequently, the official OECD

documentation on the Unified Approach (OECD 2019a, 2019b, 2020a), the OECD webcasts (OECD

2020b, 2020c) and the lion’s share of reactions by various commentators (OECD 2019c) are all quite

qualitative in nature.

Given this problem with data-availability, this paper adopts a pragmatic research approach

combining different types of research; (i) A logical approach by looking at the coherence of the rules

of the Unified Approach from both an advanced economy and developing country perspective.

(ii) An evaluative approach by examining if the OECD proposals, both separately and in connection to

each other, can work in practice taking into account differences between advanced economies and

2 Specifically, the effects of Amount A, Amount B of Pillar One, and the Income Inclusion rule and the undertaxed Payments

of Pillar Two.

3 These could also include other types of taxation, however in this paper I will not reflect further on other taxes as

alternative revenue sources

4 This estimate only concerns tax avoidance and does not include other causes of revenue loss, such as corruption or tax

evasion. Even though these illicit activities could lead to huge sums of lost revenues, such illegal activities is outside the

scope of this paper.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

4

developing countries. As well as examining if the proposals are in line with the overall objectives, the

desired political aim and looked-for economic effects. And (iii) an empirical approach aimed at

finding the best (legal) means to achieve the OECD overall objectives and thus suggesting a number

of alternative policy options that could be explored instead of/in addition to the OECD proposals.

In order to quantify the effects of the OECD Unified Approach this paper relies on a number of

objective data sources, such as the databases and research of OECD, World Bank, IMF and the

United Nations. So, no own data has been collected for this paper through, for instance, surveys or

questionnaires 5. Where no publicly available data could be found to directly quantify the effects, or

where that data is lacking in level of detail, approximations have been made based on the combined

data from these public sources as well as a number of reasoned assumptions. It is clearly indicated in

the paper where such estimates have been made and what they are based on. Moreover, through

either deductive or inductive reasoning a secondary approach has been used where possible to test

if the initial assumptions and their subsequent conclusions can hold.

By way of example, in order to assess the tax revenue impact of Amount A estimates are necessary

to determine how much of the reallocated profit would go to market jurisdictions that are advanced

economies and which share is distributed to developing country markets. A proper assessment

would require insight in firm-level data on the relevant sales of digital services in developing

countries. By way of proxy these relevant sales have been estimated based GDP levels of advanced

economies in relation to developing countries 6. Likewise, to properly assess the tax revenue impact

of Amount B would require insight in a large enough sample of firm-level transfer pricing

documentation to determine the intra-group spending on marketing and distribution services. As

these data are not available, they have been deduced from data on global corporate spending on

these services.

The use of these kind of proxies inevitably means that the calculations in this paper are subject to a

rather large degree of uncertainty. The presented results, even though they are quantified in order

to give more insight in the implications of (the separate elements of) the Unified Approach for

developing countries, should be understood as such.

2.2. Key findings

The Unified Approach proposals could allow developing countries to collectively recover a total

amount of extra tax revenue somewhere in the range of 15 to 30 billion USD. The presented range is

so wide, because the key parameters of all the separate proposals are still under discussion and

certain assumptions have to be made as essential (firm-level) data is not publicly available. In any

event, it is not an insignificant amount.

The analysis in this paper shows that there are big differences per measure in both their revenue

effects and their degree of complexity. Moreover, it shows that if the total amount of extra tax

revenue for the developing world is translated in extra revenue for individual developing countries

the revenue effects appear to be rather modest.

There are strong indications that specifically Amount A will not yield a significant amount in extra tax

revenue to (individual) developing countries, especially not if one factors in the complexity of the

5 The findings in this paper could however be the jumping off point for further research that would include more in-depth

data collection directly from multinational corporations and/or cross-referencing with data that tax authorities should have

(exclusive) access to.

6 It is fully acknowledged that GDP might be a poor indicator to determine relevant sales, as it can be artificially elevated in

low tax jurisdictions relative to the size of the market and therefore could distorting results. For that reason, also trade

levels, the developing countries’ share in world exports of goods and services and that total MNC assets in developing

countries have been considered as a proxy for determining relevant sales.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

5

new rules and how many (additional) resources it would require for developing countries to

correctly administer them. So, perhaps developing countries should flat-out reject amount A as too

complicated for too little extra tax revenue and push the G20/OECD Inclusive Framework towards a

solution that has amount B as a much more central element 7, as this proposal is potentially more

interesting for developing countries as well as easier to apply.

There is, however, remarkably little data available on Amount B. It could also be that Amount B does

not quite deliver significantly more tax revenue to developing countries either and/or that applying

Amount B would also be far from easy. Whether or not Amount B will prove worthwhile, hinges very

much on the negotiations on the technical specifications and parameters currently underway in the

Inclusive Framework. Specifically, on the question what the fixed renumeration of marketing and

distribution services will be. This renumeration needs to be quite a bit higher than the current

transfer pricing rules allow for, if Amount B is to be of real interest to developing countries.

Finally, given the current state of play one could expect that the final design of Pillar Two could be

such that it (i) is aimed more at protecting the tax base of residence countries than that of source

countries (Keen et al 2019, para 53) and (ii) will be complex due to the chosen level of blending

(OECD 2020a, para 11) 8. Moreover, the amount of extra revenue is very dependent on the level of

the effective minimum tax rate. Consequently, further work in the Inclusive Framework on these

issues could also make Pillar Two lose its appeal for developing countries.

Given these uncertainties, it could serve developing countries’ interest to argue for a third option.

One that effectively bypasses both Pillar One and Pillar Two obligations altogether. Moreover, both

developed and developing countries could benefit from a solution that ensures that also developing

countries can effectively apply the new rules.

This could be achieved by proposing that in-scope companies can opt to consolidate all their

activities in the market jurisdiction into the residence country and consequently award a fixed

percentage of the total consolidated tax revenue (rather than then a part of the tax base) to the

market jurisdictions. Thus, developing countries could actually gain corporate tax revenue by giving

up taxing rights to residence countries.

In any event, developing countries could push for wide support for a global Marshall Plan to help

countries fight and recover from the Covid-19 pandemic. This could, at least, ensure that the current

shortfall will not grow even larger as also many advanced economies face growing deficits as a result

of emergency measures to combat Covid-19. And it could conceivably (temporarily) increase the

contributions that advanced economies provide in ODA, for instance through the forgiveness of

government debts. Such a measure would, in fact, not actually increase government expenditure

levels for donor countries but would help developing countries greatly in bolstering their financial

position and, thus, increase their ability to combat the pandemic and the fall-out afterwards.

7 One could question if developing countries can really influence the outcome of the OECD/Inclusive Framework

negotiations. The OECD has many times expressed that all countries in the Inclusive Framework operate on an equal

footing. In 2017 the OECD explained how the Inclusive Framework is designed and what the phrase on equal footing means

and how the decision process takes form. So, on paper developing countries in the Inclusive Framework can contribute in

the consensus-based decision-making process as much as any other country can. I can offer no objective, empirical

evidence that this does not also work like this in practice. It can, however, be observed that the issues raised by countries

such as the US appear to be more prominent in the discussions than the issues this paper addresses.

8 This refers to discussion in the G20/OECD Inclusive Framework whether the effective tax rate has to either be calculated

on the global level, the level of a single jurisdiction or per separate entity. The discussion tends towards blending on the

level of the jurisdiction.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

6

3. Show them the money! 9

Total government revenues of developing countries amounted in 2012 to about 6,9 trillion USD

(UNCTAD 2015, 185). About half of that stems from corporate contributions. The other half comes

from personal income taxes, indirect taxation and other revenue sources, such as concessions,

grants and also development aid. The latter category is often overlooked in tax studies but is very

relevant for developing countries: also, in terms of missed revenue.

3.1. Advanced economies miss own ODA target by 191 billion USD

The best-known target for international aid is that donor countries offer 0.7% of their Gross National

Income (GNI) in Official Development Assistance (ODA) (OECD no date a). In the UN Resolution of 24

October of 1970, the following commitment was assumed:

“Each economically advanced country will progressively increase its official development

assistance to the developing countries and will exert its best efforts to reach a minimum net

amount of 0.7% of its gross national product at market prices.” (UN no date a)

At subsequent UN conferences and other international summits many developed countries

reaffirmed they would hit the target by 2015. For instance, in 2005 the EU Member States pledged

to increase ODA to 0.7% of GNI by 2015 and included an interim target of 0.56% by 2010. The EU

Heads of State and Government reaffirmed their commitment to reach the 0.7% target by 2015 at

the European Council on 7/8 February 2013 (European Commission 2013).

It is common knowledge that the target has not been hit yet. The margin by which countries have

missed the mark is however quite astonishing. The gap is now a whopping 191 billion USD (UN no

date b). In fact, figure 1 shows that on average the ODA contributions have fallen since 1960. Not

only did economically advanced economies not live up to their repeatedly given commitments,

collectively they are falling short further and further. There are only 6 countries (out of 45) that

contribute more than 0.7% of their GNI 10.

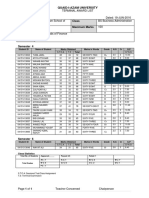

Figure 1

Source: (OECD no date b)

9 Based on the line spoken by the character Rod Tidwell, played by Cuba Gooding, Jr., in the film Jerry Maguire, directed by

Cameron Crowe (1996).

10 These countries are Denmark, Luxembourg, Norway, Sweden, Turkey and the United Arab Emirates. Close to the target

are the UK (0.699%), Germany (0.667%) and the Netherlands (0.604%).

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

7

One could argue that developing countries would be in a much better position if the advanced

economies simply would have done what they have committed to do. However, under the current

circumstances the more important question is how likely it is advanced economies will start living up

to their commitments any time soon.

The OECD estimates that due to Covid-19 tax revenues – also in advanced economies – will drop by

about 30% (OECD no date f). This makes it likely that in the short-term countries will try and cut back

on spending to prevent too large deficits. ODA expenditures might be a prime candidate for such

cutbacks. For developing countries, this would be a disastrous development, as this would diminish

already inadequate – and as a result of the effects following Covid-19 further dwindling (UNCTAD

2020, 8) – resources much faster than any plan to reallocate tax base, could hope to compensate for.

On the other hand, on a global policy level the outbreak of the Covid-19 virus has given rise to

support for designing a global ‘Marshall Plan’ (OECD 2020c, slide 24). This could lead to a

(temporary) larger contribution to developing countries, for instance through the forgiveness of

government debts. This could significantly bolster developing countries’ financial positions and help

them weather the Covid-19 storm.

3.2. Stop 100 billion USD in tax avoidance, without hurting underlying investments

The UN estimates that developing countries lose about 100 billion USD in tax revenue 11 due to tax

avoidance (UNCTAD 2015, 200) 12. This amount is directly related to inward investment stocks linked

to offshore investment hubs. This estimate therefore only regards tax avoidance and does not

include other causes of revenue loss, such as corruption or tax evasion.

Figure 2

11 Based on the current international tax rules that arguably favour advanced economies over developed countries,

meaning that advanced economies already get a larger share of the global tax revenue than developing countries.

12 This is about 23% of the tax revenue developing countries receive from foreign investors. Or, about 0,4% of the collective

GDP of developing countries.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

8

Source: (UNCTAD 2015, 189)

There is a clear relationship between the use of investment hubs and the taxable rate of return on

foreign direct investments in developing countries (UNCTAD 2015, xiii). On average, across

developing economies, every 10 percentage points of offshore investment is associated with a 1

percentage point lower rate of return. These findings, however, falsely suggests that just by putting

(enough) measures in place to fight tax avoidance, that developing countries could recover 100

billion USD in extra tax revenue. At least three points have to be considered regarding the UN

estimate.

i. The objective should be to raise the total revenue developing countries collect, not to gain a

pyrrhic victory in the tax avoidance battle. UNCTAD points out that developing countries need

inbound investments (UNCTAD 2015, 210). Even though tax avoidance reduces their tax revenue

with 100 billion USD, developing countries are able to collect 725 billion USD in revenues from

their foreign investors. Economies are not zero-sum games 13. Too stringent measures to battle

tax avoidance could have as an unintended effect that investments will not take place at all or

will take place elsewhere. This would effectively reduce the tax revenue, rather than raise it.

Therefore, there has to be a balance between those measures to prevent tax avoidance and

those to stimulate investment (UNCTAD 2015, 207).

ii. There is fierce competition amongst developing countries for foreign investment. UNCTAD

shows that tax is a very important determinant for where investments take place, more so than

is commonly believed (UNCTAD 2015, 177). Besides, it is not only the level of taxation, but also

the corresponding administrative burden and the long-term (political) stability and predictability

that are important drivers. This (also) has caused developing countries to compete between

each other to attract the foreign investments. Often by offering substantial tax advantages to

foreign investors that are not available to local competitors (Rosenzweig 2010, 995). These types

of beggar-thy-neighbour policies structurally drive down tax revenues across developing

countries (Keen and Brumby 2017). Therefore, there is a need for more intelligent (collective)

measures to stimulate investments across developing countries. A minimum tax rate as

suggested in Pillar Two (OECD 2019d, 2020a, 27-8) could be beneficial in protecting developing

countries from the sort of harmful tax competition in the corporate income tax area that is

currently very much too common. Similarly, the third option described in paragraph 6. of this

paper could be advantageous in this regard.

iii. The UN data predates the entire OECD Base Erosion and Profit Shifting (BEPS) project 14. So,

there is a measure of uncertainty what the estimate would be today. For instance, the

divergence of formal tax rates was a key driver in the 2015 OECD estimates on tax avoidance

(Næss-Schmidt forthcoming, 2). Over the last few years, however, CIT rates the world over have

been converging strongly towards the 20-25% range. Moreover, BEPS measures that have since

been implemented (OECD 2019e) should have taken away at least some the incentives to route

investments through investment hubs. Additional BEPS measures, such as a minimum tax rate

(Pillar Two) (OECD 2019d, 2020a, 27-8), should act further to break the relationship between

investment hubs and the taxable return on these foreign investments. More quantitative

research is therefore needed to determine the effects of measures already in place or planned

and thus to more accurately quantify the level of tax avoidance the developing countries still

face today.

13 A zero-sum game is a concept from game theory describing a situation where, if one party loses, the other party wins,

and the net change in wealth is zero.

14 The reference year for the UN data is 2012.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

9

4. The OECD Unified Approach from a developing country perspective

The OECD Unified Approach consists of a number of separate proposals in two pillars to address the

tax challenges posed by the digitalization of the global economy. Pillar One introduces (i) a method

to reallocate a portion of the residual profit of Multinational Corporations (MNCs) to market

jurisdictions (Amount A) and (ii) a fixed renumeration for marketing and distribution activities to

increase the tax base of market jurisdictions (Amount B). Also, in Pillar One there is a separate

workstream focused on enhancing dispute resolution, for instance as a result of disputes over

Amount A or B calculations (Amount C). Amount C will, however, not be further addressed in this

paper. Pillar Two effectively introduces a global minimum tax rate for profit taxation. The two main

proposals in Pillar Two are (i) an income inclusion rule regarding outbound investments and (ii) an

undertaxed payment rule regarding inbound investments.

These proposals should give developing countries pause. These are each highly technical proposals

in their own right and together they interact and are interdependent in very complicated ways. They

are, as such, more designed for advanced economies than the developing world (Lammers 2020,

179). For, effectively administering the proposals requires a sophisticated and mature legal and

financial infrastructure, an able tax administration and companies that have well-established (tax)

control frameworks and reporting procedures. Besides, there is the question how much extra tax

revenue the separate proposals will really give developing countries and if that extra revenue is

really worth the additional effort and resources it would require. These questions will be further

examined in the following paragraphs for each of the proposals.

5. Amount A; too much work for too little reward

That the Unified Approach proposals need a mature and sophisticated legal and financial

infrastructure is especially true for the Amount A proposal. This proposal effectively introduces a

new system of determining the tax base of MNCs on top of the existing system based on transfer

pricing and the arm’s length principle (ALP) (OECD 2020a, para 17). This proposal therefore adds a

new layer of complexity on top of the current ALP-based system. A system that developing countries

are already struggling with. For instance, the World Bank (Cooper et al 2017, 9) explains that many

developing economies still lack effective transfer pricing regimes, typically due to inappropriate

transfer pricing legislation and insufficient administrative capacity to effectively implement

international tax provisions. As a result, these countries might be losing significant tax revenue due

to intentional and unintentional transfer mispricing.

5.1. Layered complexity

Even though much is still undecided, the current state of play is that for Amount A at least six tests

will have to be performed (OECD 2020a, 12-4). These tests can be summarized as follows:

Test 1: Does the MNC have a global turnover of more than 750 million USD?

Test 2: Does the MNC qualify as a digital or consumer-facing company?

Test 3: Does the revenue from the relevant in-scope activities cross the minimum threshold?

Test 4: Does the MNC group net profit margin cross the minimum threshold?

Test 5: Does the calculated residual MNC group profit cross the minimum threshold?

Test 6: Do the relevant in-scope sales in the market jurisdiction cross the minimum threshold?

It is important to note that these six tests only tell what Amount A is and which markets could be

eligible for a share of the reallocated tax base. These tests still say nothing on how Amount A should

subsequently be distributed over the different eligible market jurisdictions. For this purpose, an

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

10

allocation key will need to be developed. On this allocation key the OECD says the following:

“This allocation key will be based on sales of a type that generate nexus (see section 3.1.2. for

the discussion on nexus revenue threshold). Specific revenue-sourcing rules to support its

application by reference to different business models will need to be developed. For example,

for online advertising such rules will, when possible, deem revenue to arise in the jurisdiction

where the advertising is viewed rather than the jurisdiction (if different) where the advertising

is purchased. Revenue sourcing will also be considered to address sales through independent

distributors in order to avoid possible distortions.” (OECD 2020a, para 47)

The allocation key introduces a whole new level of complexity to the proposal. Not only should be

determined what are the relevant in-scope sales, but there could be put different weight on

different types of sales 15. Also, advertising sales might have to be re-assigned to different

jurisdictions then they were purchased.

Nothing about these tests or the allocation key suggests that developing countries were top of mind

when designing this approach. In fact, one could argue that developing countries will have to free up

a lot of resources to build the capacity to comply with these new rules. The question is if developing

countries will be able to do so.

5.2. A drop in the bucket

In earlier research I have contended that even though Amount A will reallocate tax base to market

jurisdictions, it will not actually give these market jurisdictions access to significantly more tax

revenue (Lammers 2020, 179). According to the latest OECD economic impact assessment (OECD

2020b, slide 12) Amount A will reallocate about 2% of the profit before tax of companies that are in

scope 16. However, since the companies that will be in scope operate all over the world, the 2% share

will have to be distributed across many jurisdictions.

Furthermore, even though OECD contends that the scope of Amount A goes beyond primarily US-

based digital companies, in reality it does not (Lammers 2020, 178). The combination of parameters

for determining if tax base should be reallocated under amount A (OECD 2020a, para 21-46) in

practice will target almost exclusively digital business models. This becomes more apparent by way

of deduction. By looking beyond the definition of what constitutes a consumer-facing company, and

simply determining which companies would be left if the other tests to determine the residual profit

– in particular test 4 on profit margin – are applied.

For, only a handful of sectors in the S&P500 achieve higher than average profit margins (CSIMarket

no date a). Further analysis shows that almost all of the (best-performing) companies in these

sectors are, in fact, digital companies (CSIMarket no date b). IMF data also (at least indirectly)

supports these findings, as they point out that the MNCs with the highest residual profits are very

‘intangible-heavy’ (Beer et al 2020 20-1), as well as that these residual profits are highly

concentrated in companies headquartered in the US (Keen et al 2019, 41). Moreover, the OECD

points out that more than half of the globally reallocated profit comes from 100 MNC groups (OECD

2020b, slide 13). Besides, OECD explains that ‘mere sales without a physical presence’ is not enough

to assume a new nexus for other than digital companies that would qualify under the tests (OECD

2020a, para 39). Even though none of these arguments in and of themselves conclusively point to an

15 There have been proposals that use proxies based on a number of factors to give expression to these different weights:

for instance, the CCCTB to allocate tax base to the different EU Member States based on the factors sales, assets and

personnel, as well as in India in the draft report of 18 April 2019 by India’s Central Board of Direct Taxes (CBDT) on the

profit allocation to PEs on similar factors.

16 With residual profit defined with a 10% threshold on profit-before-tax to turnover, and assuming a 20% reallocation of

residual profit to market jurisdictions.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

11

agenda to exclusively target digital companies, put together they make a compelling case.

Assuming that digital companies will be the major contributors to the reallocated profits as a result

of Amount A, it serves to look at how much profit some of the most prominent digital companies

actually make and what would then be reallocated to market jurisdictions (as shown in table 1).

Consequently, an estimate can be made of how much of the reallocated profits would actually go to

developing countries.

Table 1

profit before tax profit margin extra tax revenue on

(bln) average per market

(mln)

1 Apple 67 25,30% 9,3

2 Alphabet 39 23,20% 4,7

3 Alibaba 28 39,40% 7,4

4 Facebook 24 35,10% 5,4

5 Amazon 14 5,00% 0,0

6 Booking 5,2 34,60% 1,1

Sources: (CSIMarkt

7 Netflix 2 10,20% 0,0

no date a, no date

8 Weibo 0,7 36,95% 0,2

b) (OECD 2020a)

9 Twitter 0,4 11,30% 0,0

and own

10 Baidu -0,8 -5,50% 0 calculations

In 2019 the combined pre-tax profit of these 10 prominent digital companies was about 180 billion

USD. Assuming an average corporate income tax rate of 25%, would mean that all market

jurisdictions combined would get an additional total tax revenue of about 1.500 million USD 17. This

amount would, however, have to be shared with a number of market jurisdictions. In the case of

Alphabet most likely with over 55 jurisdictions (Blum and Seiler 2016, 92). Assuming a somewhat

comparable global coverage for the other digital MNCs, on average a market jurisdiction would get

no more than about 30 million USD from all these companies combined 18. Or, for every billion in

reallocated profit a market jurisdiction can on average expect not more than about 150.000 USD in

extra tax revenue.

Even though table 1 already makes a compelling point, for developing countries the extra tax

revenue would lie well below these average numbers. For, the reallocated profit should be

distributed between eligible market jurisdictions on the basis of relevant sales (OECD 2020a, para

47). This would give larger, richer markets a larger share of the reallocable profit. Other

commentators have also pointed this out (see for instance Cobham et al 2019, 16 or Christians and

Magalhaes 2019, 1175). OECD does appear to recognize this issue as they allude to that there could

be some consideration as to the market jurisdiction’s size (OECD 2020a, para 46). It is therefore to

be expected that a more intelligent metric than just sales will be included in a final proposal. One

could, for instance, imagine that the distribution of the reallocated tax base would be fairer 19 if it

were based on a division by sales corrected for the size of both the market and the jurisdiction’s

GDP, or a division based on the market share per competing jurisdiction. Also, other metrics

(complementary to sales) could be used, for instance employment (Cobham et al 2019, 21) or

possibly even a jurisdiction’s development needs. However, as of yet this is not the case.

17 Using the same parameters as the OECD did in their economic analysis. With residual profit defined with a 10% threshold

on profit-before-tax to turnover, and assuming a 20% reallocation of residual profit to market jurisdictions.

18 As not all of these companies offer publicly available information on the number of countries where they have a physical

presence for corporate income tax purposes and where they perform sales without such a physical presence, it is

necessary to make an assumption. To illustrate that the assumption will not lead to an underestimation: following investor

relation information, Amazon serves customers in about 180 countries and has offices (fulfillment centers, warehousing,

software development centers and datacenters) in no more than 50 countries worldwide (Amazon.com no date)

19 Or at least more beneficial to especially developing countries.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

12

To assess how much tax base would be reallocated to developing countries, some assumptions are

necessary 20. First, for the purposes of this paper all low- and middle-income countries as recognized

by the World Bank (World Bank no date) are considered to be developing countries 21. Second, as a

proxy for the relevant sales for Amount A the overall GDP of developing countries (2018) relative to

global GDP (2018) can be used (OECD no date c, World Bank no date). Based on these variables,

developing countries would be entitled to almost 37% of the reallocable profits. Instead of 150.000

USD per billion in reallocated profit, a developing country would therefore be more likely to receive

about than 110.000 USD in extra tax revenue per billion in reallocated profit.

One could also consider global trade levels as a proxy for determining relevant sales. Developing

countries have seen their share of world trade grow steadily between 2000 and 2012. Since 2012 the

growth has been more or less in step with the growth in the advanced economies. The share in

export of goods in 2019 was 44.3% and that of services 30.0%. For both goods and services, the

share in world exports is just over 41% (UNCTAD 2020a). However, by far the main exporters in the

category of developing countries are China, India and Singapore. Besides, trade levels – especially

those of developing countries – are very strongly affected by Covid-19.

A recent IMF working paper on residual profits introduces very interesting firm-level data on the

10,000 largest MNCs recorded in the S&P Capital IQ database for 2011-2017. IMF found that of

these MNCs less than 33% have their headquarters in developing economies (Beer et al 2020, 12).

These MNCs own less than 30% of the total fixed assets and get about 20% of the global pre-tax

profits 22. Based on these figures developing countries would get no more than between 60.000 and

70.000 USD in extra tax revenue per reallocated billion USD in profit 23.

However, the IMF data also does not offer any definite insight into the relevant sales under Amount

A for a more accurate assessment of likely profit allocation. Therefore, for the purpose of this paper,

it will be assumed that developing countries could legitimately claim up to 37% of the reallocable

profits. Also, this way the total effects of the Unified Approach presented further on in this paper are

20The OECD Activities of Multinational Enterprises (AMNE) database provides detailed data on the activities of foreign

affiliates of MNCs based in OECD countries. However, there is very little reliable data on the relevant (online) sales to

developing countries by MNCs (or their affiliates) without a physical presence in these developing countries. For the

purpose of determining what share of relevant sales takes place in developing countries more detailed data is required.

Therefore, the AMNE database does not give a reliable indication how the reallocated profits under Amount A should be

divided between developed and developing countries.

21This constitutes a list of 138 countries:

Afghanistan, Albania, Algeria, American Samoa, Angola, Argentina, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Bangladesh, Belarus, Belize,

Benin, Bhutan, Bolivia, Bosnia And Herzegovina, Botswana, Brazil, Bulgaria, Burkina Faso, Burundi, Cabo Verde, Cambodia,

Cameroon, Central African Republic, Chad, China, Colombia, Comoros, Congo, Dem. Rep., Congo, Rep., Costa Rica, Cote

D'ivoire, Cuba, Djibouti, Dominica, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Egypt, Arab Rep., El Salvador, Equatorial Guinea, Eritrea,

Eswatini, Ethiopia, Fiji, Gabon, Gambia, The, Georgia, Ghana, Grenada, Guatemala, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Guyana, Haiti,

Honduras, India, Indonesia, Iran, Islamic Rep., Iraq, Jamaica, Jordan, Kazakhstan, Kenya, Kiribati, Korea, Dem. People’s

Rep., Kosovo, Kyrgyz Republic, Lao Pdr, Lebanon, Lesotho, Liberia, Libya, Madagascar, Malawi, Malaysia, Maldives, Mali,

Marshall Islands, Mauritania, Mauritius, Mexico, Micronesia, Fed. Sts., Moldova, Mongolia, Montenegro, Morocco,

Mozambique, Myanmar, Namibia, Nauru, Nepal, Nicaragua, Niger, Nigeria, North Macedonia, Pakistan, Papua New

Guinea, Paraguay, Peru, Philippines, Romania, Russian Federation, Rwanda, Samoa, Sao Tome And Principe, Senegal,

Serbia, Sierra Leone, Solomon Islands, Somalia, South Africa, South Sudan, Sri Lanka, St. Lucia, St. Vincent And The

Grenadines, Sudan, Suriname, Syrian Arab Republic, Tajikistan, Tanzania, Thailand, Timor-Leste, Togo, Tonga, Tunisia,

Turkey, Turkmenistan, Tuvalu, Uganda, Ukraine, Uzbekistan, Vanuatu, Venezuela, Rb, Vietnam, West Bank And Gaza,

Yemen, Rep., Zambia, Zimbabwe

22 Of these total fixed assets 27,8% is in emerging economies and 0,1% in low-income countries. Of the total pre-tax profits

19,8% are attributed to emerging economies and 0,1% to low-income countries.

23 IMF data shows that the MNCs in the sample set have a higher ETS in emerging markets (22.2%) and low-income

countries (21.4%) than in advanced economies (20,1%).

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

13

less likely to be subject to underestimation. The UNCTAD and IMF figures, however, do illustrate that

a large degree of uncertainty remains as to the accuracy of the projected effects. This goes for both

the estimates as put forward by the OECD as well as those presented in this paper.

6. Amount B; still a dark horse

Amount B gets too little airtime. In fact, it is remarkable how little information is available on the

effects and impact of amount B (OECD 2020b). Let alone information on how much developing

countries could expect to gain in tax revenue by this measure. It is unclear why the OECD has

decided to not include the effects of amount B in their economic analysis 24.

In the latest OECD publications, no more than a few high-level paragraphs have been dedicated to

Amount B. Also, most commentators focus (mostly) on Amount A 25. A possible explanation for this is

that Amount B stays very close to the international tax rules we have today. In essence, it is

supposed to attribute a larger share of the MNC group profit to activities in countries in which the

company is selling goods and services (OECD 2020a, 16). For this, amount B focuses on distribution

and marketing functions. It does not in and of itself create new taxing rights for economic activities

without a physical presence.

Amount B, therefore, fundamentally is (only) an adjustment of the existing arm’s length system.

Even though these rules are far from easy to apply, at least all actors have experience in applying

them. This should make Amount B considerably easier to apply than Amount A (Næss-Schmidt

forthcoming, 3). And it should from a technical and political perspective be far less controversial.

However, up till now the exact parameters remain unclear. This might be the case until the technical

work on the features of Amount B is finished in November 2020 26.

6.1. Administrative relief or hidden complexities?

Amount B might free up government resources. OECD expects the fixed returns of Amount B will

allow both tax administrations and taxpayers to devote less time and effort to these activities (OECD

2020a, para 59). Also, standardized rules should serve to prevent future tax disputes. These effects

would be especially relevant for developing countries.

However, developing countries might still struggle with applying the new standardized rules. The

question is how easy it will be to determine the fixed remuneration for baseline marketing and

distribution functions that take place in their jurisdiction (OECD 2019b, para 62-3). This could be

further complicated depending on definitions of the qualifying activities and income, and/or if these

rules would differ across industries (OECD 2020a, para 60). It is therefore too early to tell if and to

which extent developing countries will benefit in terms of administrative costs.

6.2. Reshuffling global tax revenues

There is virtually no data on the economic impact of Amount B. The OECD provides no indication of

the level of the intended fixed returns or how these would translate into profit allocation to market

jurisdictions. There is no indication how much more (or less) this would be compared to profit

allocation under current rules. There are no figures on the current AETR of these activities, or what

these would be under Amount B. OECD has left all figures concerning Amount B out of their

presentation of the economic effects of the unified approach. It is unclear why the OECD chose to do

24 The OECD economic analysis only shows the effects for Amount A in Pillar One.

25 See for instance the 169 public comments received by the OECD on the Secretariat Proposal for a "Unified Approach"

under Pillar One (OECD 2019c)

26 The OECD secretariat explained in the webcast on May 4, 2020 (OECD 2020c) that even though great progress has been

made on Amount B by the members of the Inclusive Framework in Working Party 6 of the OECD it was also agreed by the

members that details could not yet be shared.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

14

this. It could be because from a global perspective, Amount B should generate no or very little extra

tax revenue 27. However, from the perspective of developing countries the tax base shift that

Amount B will cause, is very relevant. It is also possible that the data simply is not yet available, and

that OECD is still compiling the data parallel to the technical work on Amount B.

It is therefore (at the time of writing) very difficult to accurately assess how much extra tax revenue

developing countries could expect as a result of Amount B. For the purpose of this paper, the

possible revenue effects of Amount B will be put in perspective by making a number of assumptions.

First off, it is assumed that the relevant services only flow one way, from developing countries to

advanced economies. This means that a higher fixed percentage on these services would increase

the tax base in developing countries and cause higher (deductible) costs in advanced economies.

Second, OECD data shows that total corporate income tax revenue for all OECD countries combined

in 2018 is 3.03% of total OECD GDP (OECD no date c), or about 1.8 trillion USD. It is assumed that a

range of 3.5 to 7.5% of that revenue is connected to relevant marketing and distribution services 28

and that the Amount B parameters are set to effectively increase the AETR on this income by 10%.

That would mean that (theoretically) the total extra tax revenue could amount to somewhere in the

neighbourhood of 6.5 to 13.5 billion USD. Of course, if one would assume that the G20/OECD

Inclusive Framework would push for no more than a 5% hike in the AETR for these services, the extra

tax revenue would fall in a range of 3.2 to 6.8 billion USD.

Assuming a similar division of the revenue between high income countries and developing countries

as above 29, Amount B would give developing countries access to an extra tax revenue between 1.2

to 5 billion USD. It is fully acknowledged that the outcome of the OECD negotiations regarding

amount B most likely will differ from the outcome presented here, but the aim of this calculation

and its underlying assumptions is not to predict the exact parameters of amount B. The aim is to

provide a ballpark figure to illustrate the impact Amount B could have on tax revenues in developing

countries.

6.3. Second order effects

In addition to outright revenue gains, developing countries might benefit from Amount B for other

reasons. A second order effect of Amount B could be that it solves a lot of current transfer

mispricing problems. Developing countries currently lose revenue due to transfer mispricing as they

often lack proper national transfer pricing legislation and/or the resource to argue against

sophisticated transfer pricing reports from MNCs (Cooper et al 2017, 9). A fixed percentage for

marketing and distribution services could help strengthen the negotiating position of tax

administrations. Also, this would substantially ease the current transfer pricing burden on

developing countries, and it could serve to prevent costly, difficult and resource-demanding

disputes.

Furthermore, fixed percentages could lead to an overall increase in effective tax rates even if the

fixed percentages are comparable to current profit margins. The reason for this is that the nominal

27 As the extra income in source countries would be cancelled out by the extra costs at the level of the residence country.

Extra tax revenue (on a global level) could conceivably only come from differences in corporate income tax rates. Contrary

to Amount A, it is unlikely that through Amount B previously untaxed income would be unearthed.

28 Global logistics expenses are estimated between 9.000 and 10.500 billion per year. Global advertising expenses run up to

about 600 billion USD, of which 100 billion USD is in digital marketing. At profit margin between 5 to 10% these expenses

translate to a total estimated tax revenue between 120 and 275 billion USD, or between 7 and 15% of the total OECD

corporate income tax revenue. This, however, would be an overestimation, as total global expenses would include more

than just intra-group expenses. Since intra-group trade makes up about 50% of world trade the assumption is that

currently intra-group marketing and distribution functions yield somewhere between 3.5 and 7.5% of the total OECD CIT

revenue. (Statista.com no date), (Reuters.com no date a, no date b), (Suppychaindigital.com no date)

29 See page 12

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

15

tax rates are usually higher in developing countries than in developed countries and investment

hubs (Asen 2019, 10). On the other hand, in practice developing countries often offer substantial tax

advantages to foreign investors that are not available to local competitors. Therefore, the nominal

tax rate alone is not enough to determine whether the tax differential would, in fact, lead to an

overall increase of effective tax rates due to Amount B.

6.4. Too soon to say

Applying a fixed percentage for routine marketing and distribution functions could be far easier,

more cost-effective and efficient for market jurisdictions than reallocating a portion of the residual

profit. This most likely is true with regards to the administrative costs and resources necessary to

apply these rules. If this is also true in terms of tax revenue will have to remain to be seen.

The latter point is particularly uncertain. Residence countries could very well feel that amount B

would be too large a drain on their tax revenue as this reallocation of the tax base would (typically)

lead to higher deductible costs in their jurisdictions. Residence countries could therefore argue that

the fixed percentage should, in fact, effectively increase the AETR of marketing and distribution

services by a much smaller degree than the assumed 10% (or 5%) above. In that case, the extra tax

revenue for developing countries will rapidly dwindle. Therefore, putting all of the developing

countries’ eggs in the Amount B basket hoping to get access to significantly more tax revenue might

prove to be a short-sighted strategy.

Without more clarity as to both the parameters of Amount B and the availability of better firm-level

data it is too early to make a proper assessment of its potential impact on tax revenue and

investment levels. Consequently, it is too soon to say whether developing countries will really

benefit.

7. Pillar Two; six times the size of Pillar One

The Pillar Two proposals should in essence set a global minimum tax rate. It gives countries the right

to tax back profit that is currently taxed below the set minimum rate and/or deny deductions for

certain payments (OECD 2019d, para 5) (OECD 2020a, para 8-17). The minimum rate could either be

applied globally, on a jurisdiction-by-jurisdiction basis or even on an entity-by-entity basis (OECD

2019d, para 52-73) (OECD 2020a, para 11).

The Pillar Two proposal look to offer the most in terms of extra tax revenue globally. However, from

a developing country perspective it matters a lot which approach in Pillar Two takes precedence.

This is because developing countries typically have more inbound than outbound investments.

The Income Inclusion rule operates as a top-up tax to a minimum rate that is yet to be

determined. This rule focuses on outbound investment. As the design is inspired by CFC-

rules, it aims to protect the tax base of the parent jurisdiction by preventing MNCs from

moving activities to low tax jurisdictions or put in place intra-group financing structures

(OECD 2020a, 28).

The undertaxed payments rule works by denying a deduction or making an equivalent

adjustment in respect to intra-group payments (OECD 2020a, 29). This rule therefore

focuses more on inbound investment. As such, it is designed to protect the tax base of the

subsidiary jurisdiction.

The May 4, 2020 webcast (OECD 2020c) revealed that much is still hidden behind Pillar Two.

Essentially all that was explained, was that the Inclusive Framework has not yet reached consensus

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

16

on any of the building blocks of the separate proposals, as illustrated in the infographic below 30.

However, the current state of play in the G20/OECD Inclusive Framework discussion appear to be

that the Undertaxed Payments rule should act as a backstop to the Income Inclusion rule (Tax Policy

Center 2020). This is relevant for developing countries, as the Undertaxed Payments rule would

actually be better suited to protect their tax base (Keen et al 2019, para 53).

Figure 3

Source: (OECD 2020c, slide 51)

7.1. Possible second order effects

It is important to note that even though the income inclusionary rule is more advantageous to

residence countries, this does not mean that source countries could not benefit. For, it is very likely

that the implementation of Pillar 2 based on the income inclusion rule would trigger a policy

reaction in developing countries national legislation. It makes sense to assume that developing

countries would raise their national (effective) tax rates to the minimum level of Pillar 2. This could

raise tax revenues on foreign investments in developing countries.

On the other hand, Pillar 2 could in practice turn out to be both a minimum and a maximum tax rate.

This would be the case if the minimum level of taxation of Pillar 2 in practice also effectively

functions as a cap, forcing global rates to quickly converge on this exact point 31. This would de facto

limit both advanced economies and developing countries in their freedom to set their own

corporate income tax rates. It is unclear what the effect of such a (forced) global converging of rates

would be on investment levels in particularly developing countries, given the fact that currently the

cost of capital in emerging markets can be up to 1.5 or 2 times higher than in advanced economies

(Cobham et al 2019, 10. Besides, investment decisions are also much dependent on levels of

administrative burden, long-term (political stability) and predictability (UNCTAD 2015, 177). It might

be that, absent the tax differential, the risk-profile for many investments in developing countries

would become too high compared to that of comparable investments in advanced economies.

Also, this convergence effect could trigger a host of new areas of creative (tax) competition to

attract foreign investments, especially amongst developing countries. It is important to prevent that

30 For the purpose of this paper, it is not necessary to go into further detail of these building blocks, sufficient is to mention

that at the time of writing on each of the proposals much is still unclear.

31 Rather than the more gradual convergence on a much wider range that can be observed over the last decade.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

17

one kind of harmful tax competition is replaced with another, possibly even more harmful, kind.

Therefore, also under the Unified Approach there remains a need for more intelligent (collective)

measures and guidance to stimulate investments across developing countries.

7.2. Economic impact assessment

Unlike with Amount B, the OECD has provided data on the economic impact of Pillar Two. In fact, the

OECD has done calculations on 4 scenarios (OECD 2020b, slide 16).

i. A static scenario (without behavioural reaction)

ii. Scenario 1 with interaction with Pillar One

iii. Scenario 2 with MNCs reducing profit shifting intensity

iv. Scenario 3 with a number of low tax jurisdictions increasing their CIT rates

Figure 4

Illustrative scenario on Pillar 1 and 2 design

4,00%

3,50%

3,00%

2,50%

2,00%

1,50%

1,00%

0,50%

0,00%

Scenario 1 Scenario 2 Scenario 3 Scenario 4

pillar 2: reduced profit shifting

pillar 2: rate increase in low-tax jurisdictions

pillar 2: revenues from minimum tax

pillar 1: amount A

Source: (OECD 2020b, slide 17)

These scenarios show that the OECD has looked at the effects of Pillar One and Pillar Two combined.

The same will be done in paragraph 7 below. In this paragraph these scenario’s will be further

analyzed from the perspective of developing countries and the findings in this paper will be closer

compared with those presented by the OECD.

Here it suffices to state that in the OECD representation the effects of Pillar Two are up to a factor 6

greater than Pillar One (Amount A only) in terms of global extra tax revenue. With a total increase of

tax revenue of almost 4% of global corporate income tax revenue, or about 100 billion USD, Pillar

One accounts for about 0.5% of global CIT revenue, or about 15 billion USD, and Pillar Two for the

remaining approximate 3%, or about 85 billion USD.

8. Perspectives on the OECD economic analysis

The OECD economic analysis shows that low- and middle-income countries would benefit almost as

much as developed countries. This is shown in figure 5 below.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

18

Figure 5

Illustrative scenario on Pillar 1 and 2 design

(% of CIT revenue)

4,50%

4,00%

3,50%

3,00%

2,50%

2,00%

1,50%

1,00%

0,50%

0,00%

high income middle income low income

pillar 2: reduced profit shifting

pillar 2: reduced profit shifting

pillar 1: Amount A

Source: (OECD 2020b, slide 20)

At first glance, these results seem at odds with the comments made earlier in this paper, but they

are not. The OECD choose to present their results as a share of CIT revenue. That makes the results

for low- and middle-income countries look somewhat more impressive than they in reality would be,

especially for middle-income countries 32. This group is particularly relevant, because the middle-

income countries include most countries that have large stores of natural resources. These countries

are more likely to attract larger foreign investments and, unfortunately, are therefore more likely to

be affected most by tax avoidance practices.

8.1. Impact on tax revenue

If the exact same data is presented as a percentage of GDP (figure 6), it becomes more apparent that

especially for middle-income countries the effects are minimal.

One could also look at the figures in terms of ‘compensation’ for tax avoidance. Assumptions have to

be made as to the scope of tax avoidance, but the reports from UNCTAD (UNCTAD 2015, 200) and

BEPS Action 11 (OECD 2015, para 174) as well as a number of other sources (See e.g. Clausing 2020,

and Tørsløv, Wier and Zucman 2020) 33 provide data that allows for an educated guess. In figure 7

below this perspective is depicted. Particularly this presentation of the data indicates that residence

countries stand to benefit most from the proposed measures.

32 Together low- and middle-income countries make up about two-thirds of the total number of countries in the world, but

in terms of corporate income tax revenue together they take in just over 25% of total global revenue.

33 See also https://missingprofits.world/ for a very insightful and useful interactive map that gives information per country

how much tax revenue is lost (or in some cases won) through profit shifting. Tørsløv, Wier and Zucman estimate that close

to 40% of all multinationals profits (more than 700 billion USD) are shifted to tax havens each year, reducing the corporate

income tax revenue by more than 200 billion USD, or 10% of global corporate tax receipts.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

19

Figure 6 Figure 7

Illustrative scenario on Pillar 1 and 2 design Illustrative scenario on Pillar 1 and 2 design

(in % of GDP) (in % of revenue lost in tax avoidance)

2,50% 120,00%

2,00% 100,00%

80,00%

1,50%

60,00%

1,00%

40,00%

0,50%

20,00%

0,00% 0,00%

high income middle income low income high income middle income low income

pillar 2: reduced profit shifting pillar 2: reduced profit shifting

pillar 2: revenues from minimum tax pillar 2: revenues from minimum tax

pillar 1: Amount A pillar 1: Amount A

Yet another way to present the same data, is in absolute numbers. Figure 8 and 9 respectively show

the amounts in extra CIT revenue for high- middle- and low-income countries as a group and on

average per country in that group. This presentation of the data also indicates that high-income

countries both as a group and individually stand to reap higher rewards from the Unified Approach

than low- and middle-income countries.

Figure 8 Figure 9

Illustrative scenario on Pillar 1 and 2 design Illustrative scenario on Pillar 1 and 2 design

(in bln USD) (in mln USD per country)

100,0 USD 1.800,0 USD

90,0 USD 1.600,0 USD

80,0 USD 1.400,0 USD

70,0 USD

1.200,0 USD

60,0 USD

1.000,0 USD

50,0 USD

800,0 USD

40,0 USD

600,0 USD

30,0 USD

20,0 USD 400,0 USD

10,0 USD 200,0 USD

0,0 USD 0,0 USD

high income middle income low income high income middle income low income

pillar 2: reduced profit shifting pillar 2: reduced profit shifting

pillar 2: revenues from minimum tax pillar 2: revenues from minimum tax

pillar 1: Amount A pillar 1: Amount A

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

20

8.2. Impact on global investment levels

The OECD suggests that the effects on global investments levels would be minimal, even though

there is a projected extra corporate income tax revenue of 100 billion USD. Or, at least, that the

direct effect on investments costs in most countries would be limited (OECD 2020b, slide 24). For

local investments this could very well be true, as they remain largely unaffected by these proposals.

However, it is difficult to understand how there would not be direct effects for MNC investments.

Many of these MNCs are present in investment hubs (otherwise they would not be investment

hubs). Even those companies that are not in scope for Amount A can therefore expect to be affected

to some degree by the pillar Two proposals 34.

In addition, the effects of Amount B are not yet included in the OECD analysis. Even though on a

global scale this should only mean that revenues are reallocated, higher fixed percentages for

marketing and distribution would raise ETR levels for many MNCs. For, these activities might be

subject to a higher tax rate in market jurisdiction. As figure 10 shows, even though corporate income

tax rates have both dropped and converged towards the 20 to 25% range across the world, larger

market jurisdictions and market jurisdictions in developing countries still tend to have higher

corporate income tax rates (Asen 2019, 10).

Figure 10

It is likely that a large contingent of MNCs – also for those companies that are not in-scope for

Amount A – will be confronted with the effects of the Unified Approach. Therefore, if the effect on

investment level is judged on an entity-by-entity approach, it might lead to an underestimation of

the effects. Seen through the lens of an MNC as one single entity would give a better real-world

perspective on how the effects of the Unified Approach might affect the investment decisions of

MNC, and more specifically how it would affect foreign direct investments in developing countries.

The OECD does appear to have recognized these points. They state in the economic analysis that the

impact of ETR might vary across firms and further analysis on the firm level is undertaken (OECD

2020b, slide 22).

34

Given the fact that OECD projects a structural extra tax revenue stream in all scenarios.

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

21

8.3. Finding the best way forward

As a share of tax revenue or GDP it looks like especially low-income countries will benefit

significantly from the Unified Approach. However, the amounts that are likely to be recovered do

appear very modest both in absolute terms as in comparison to what developed countries are likely

to see in extra tax revenue. This is even more so the case for middle-income countries. Also, as

argued above, the outcome of the Inclusive Framework discussion could very well mean that

revenue effects for the separate proposals (for developing countries) will be smaller than as

presented in the OECD economic impact assessment.

Furthermore, all the elements of the Unified Approach will most likely be very difficult for

developing countries to manage. As discussed above, it is unsure that they will be able to free up

enough resources to build up the capacity to deal with these new rules while also keeping up with all

the other developments in international taxation.

If this is indeed the case, then this is not only a problem for developing countries. If a large number

of jurisdictions have trouble with applying the rules of the international tax system, that will also

affect more advanced economies. The international tax system is simply to globally integrated for it

not to. This means that the issues developing countries most likely will have with the Unified

Approach cannot simply be ignored. Just forging on with the Unified Approach therefore might not

be the best way forwards. Not only would that be problematic for developing countries, but this

could very easily come back to bite advanced economies as well.

An alternative approach should therefore be investigated. A third option that generates at least the

same projected tax revenue for developing countries at but a fraction of the compliance and

administrative costs. An alternative approach that is more likely to preserve investment levels and,

possibly, to eliminate the incentive for developing countries to inflict harmful tax competition on

each other to attract the much-needed foreign investment. Possible policy options for such an

alternate approach are presented in the following paragraph.

9. Dancing at two weddings

Developing countries might be able to dance at to weddings; get more revenue from digital business

models and reduce the administrative burden of the international tax system at the same time. As

argued above, it would most likely serve the interests of both developed and developing countries if

developing countries could get out of most, if not all, requirements concerning the application of the

new rules of the Unified Approach. To this end, a number of policy options could be considered.

i. Abolishment of Amount A

This would spare developing countries at least the trouble of Amount A. It would, however,

also mean that they would get even less extra tax revenue out of the Unified Approach than

they already do. Also, they would still have to face the complexities of Amount B and Pillar

Two. Recent research (Bundgaard and Kjærsgaard 2020, 1004-5) does suggests that in many

– but not all – instances of digital business models there has to be some kind of physical

presence. This could mean that the relevance of Amount A is smaller than presented above.

For, if there is a physical presence, market jurisdictions (including developing countries)

could utilize the mechanism of Amount B to generate more tax revenue. However,

Bundgaard and Kjærsgaard also do not differentiate between developing and developed

countries. Nor do they make any definitive statements on what profits should be allocated

to jurisdictions if a digital business model has to have some form of physical presence in that

market. This option therefore still means a serious uptick in complexity, with less access to

Electronic copy available at: https://ssrn.com/abstract=3669117

22

extra tax revenue than the Unified Approach currently offers.

ii. Transfer of administrative requirements

The country of residence of the in-scope MNC could be made responsible for the calculation

of Amount A. Development countries would be spared the complexities of determining the

deemed residual profit and which countries are eligible for reallocation a share of that

profit. In short, they would get the amount of the extra tax base that would be allocated to

them and all they need to do is apply the national CIT rules to this tax base. OECD seems to

be looking into such one-stop-shop options, as part of a wide variety of implementation

simplification. However, this would require a large degree of international cooperation. This

approach would not limit the access to extra tax revenue compared to the Unified Approach