02 Handout 1

02 Handout 1

Uploaded by

Adrasteia ZachryCopyright:

Available Formats

02 Handout 1

02 Handout 1

Uploaded by

Adrasteia ZachryOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

02 Handout 1

02 Handout 1

Uploaded by

Adrasteia ZachryCopyright:

Available Formats

BM2206

COST TERMINOLOGY

Cost reveals the economic measure of resources used to accomplish an objective like manufacturing a product.

However, the term “cost” must be defined more specifically before “the cost” of a product can be determined

and communicated to others. Thus, a clarifying adjective is generally used to specify the type of cost being

considered. For example, the balance sheet value of an asset is an unexpired cost, but the portion of an asset’s

value consumed during a period is an expense or expired cost shown on the income statement.

Cost Management System – a set of recognized methods developed for planning and controlling an

organization’s cost-generating activities relative to its strategy, goals, and objectives. This system is designed

to communicate all value chain functions about product costs, product profitability, cost management, strategy

implementation, and management performance. Cost concepts and terms have been developed to facilitate this

communication process.

Cost object – Any item for which costs are being separately measured. It is a key concept used in managing

the costs of a business. Production operations and product lines are common cost objects.

Product Costs – Costs related to product-making. These costs associated with any cost object are classified

according to their relationship with the cost object.

• Direct Costs – Costs directly identified with finished goods or those that are conveniently and economically

traceable to the cost object. Examples are direct materials and direct labor.

• Indirect Costs – Costs indirectly associated with finished goods or those that cannot be economically

traced. These costs are allocated instead to the cost object. Examples are overhead costs like salaries of

supervisors and depreciation.

REACTION TO CHANGES IN ACTIVITY

To manage costs, accountants must understand how total (rather than unit) cost behaves relative to a change

in a related activity measure. Common activity measures include production volume, sales volumes, hours of

machine time used, pounds of material moved, and the number of purchase orders processed. Every

organizational cost will change if sufficient time passes or an extreme shift in activity level occurs. Thus, to

correctly identify, analyze, and use cost behavior information, a time frame must be specified to indicate how

far a cost should be examined into the future, and a particular range of activity must be assumed.

Relevant Range refers to a limited span of volume or activity. This range has two (2) extreme cost behaviors:

variable and fixed cost.

• Variable Costs vary in total in direct proportion to changes in production volume. This cost is constant on

a per unit basis as activity changes within a relevant range. As activity changes, total variable costs increase

proportionately when the activity changes, but unit variable costs remain the same. Examples are direct

materials and direct labor, fuel and other factory supplies, overtime premium, materials handling costs, and

maintenance costs.

Direct Materials P 5.00 Case A Case B Case C

Direct Labor 6.00 Production in units 8,000 9,000 9,500

Overhead 3.00 Variable cost per unit 14.00 14.00 14.00

Total Variable Costs Per Unit P14.00 Total Variable Costs P112,000 P126,000 P133,000

Total variable costs per unit are constant at P14.00, but total variable costs also increase with production

increases (Rante, 2016).

Although accountants view variable costs as linear, economists view these costs as curvilinear. The cost line

slopes upward at a given rate until a volume is reached, at which the unit cost becomes relatively constant.

02 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 1 of 10

BM2206

Within this relevant range, the firm experiences stable effects on costs such as discounts on material prices and

worker skill and productivity. Beyond the relevant range, the slope becomes quite steep as the firm enters a

range of activity in which operations become inefficient and production capacity is over-utilized. The firm finds

that costs rise rapidly due to worker crowding, equipment shortages, and other operating inefficiencies in this

range. Although the curvilinear graph is correct, it is not as easy to use in planning or controlling costs.

Accordingly, accountants choose the range in which these variable costs are assumed to behave as they are

defined, and, as such, the assumed cost behavior is an approximation of reality (Raiborn & Kinney, 2013).

• Fixed Costs are constant in total within the relevant range of activity but variable on a per-unit basis. As

the activity level increases or decreases, total fixed cost remains constant but unit cost declines or goes up.

Examples are depreciation using straight line method, factory rent, factory taxes, factory insurance,

supervision fee, and wages of indirect laborers.

Total fixed cost for the period P100,000 Case A Case B Case C

Production in units: Case 1 8,000 Production in units 8,000 9,000 9,500

Case 2 9,000 Total Fixed Costs P100,000 P100,000 P100,000

Case 3 9,500 Fixed cost per unit P12.50 P11.11 P10.53

Relevant Range 8,000-10,000 units

Total fixed costs remain the same, but the fixed cost per unit decreases as production increases within the

relevant range (Rante, 2016).

From period to period, fixed costs may change. The business volume will increase or decrease sufficiently that

production capacity will be added or sold. Alternatively, management could decide to “trade” fixed and variable

costs for one another. For example, a company that opted to install new automated production equipment would

incur a substantial additional fixed cost for depreciation but eliminate the variable cost for hourly workers’ wages.

In contrast, a company that decided to outsource its data processing function would eliminate the fixed costs of

data processing equipment depreciation and personnel salaries and incur a variable cost for transaction volume.

Whether variable costs are traded for fixed costs or vice versa, a shift from one type of cost behavior to another

changes a company’s basic cost structure. It can significantly impactrofits (Raiborn & Kinney, 2013).

A mixed cost has both a variable and a fixed component. On a per-unit basis, a mixed cost does not fluctuate

proportionately with changes in activity nor does it remain constant with changes in activity.

Understanding the types of behavior shown by costs is necessary to make valid estimations of total costs at

various activity levels. Variable, fixed, and mixed costs are the typical types of cost behavior encountered in

businesses. Cost accountants generally separate mixed costs into their variable and fixed components so that

the behavior of these costs is more readily apparent. Methods of doing this are: the High-Low Method and

Least Squares Regression Analysis

High–Low Method

This method analyzes a mixed cost by selecting the highest and lowest activity levels in a set of data within the

relevant range. Activity levels are used because activities cause costs to change, not vice versa. Occasionally,

operations occur at a level outside the relevant range (e.g., a special rush order could require excess labor or

machine time), or cost distortions occur within the relevant range (a leak in a water pipe goes unnoticed). Such

non-representative or abnormal observations are called outliers and should be disregarded when analyzing a

mixed cost.

STEPS:

1. Select the highest and lowest activity levels in a given set of data within the relevant range.

2. Determine the changes in activity and cost by subtracting low values from high values. These changes are

used to calculate the variable unit cost contained in the mixed cost.

02 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 2 of 10

BM2206

Variable cost per unit is computed as:

𝐶𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑎𝑡 ℎ𝑖𝑔ℎ 𝑙𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑙 − 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑎𝑡 𝑙𝑜𝑤𝑒𝑠𝑡 𝑙𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑙 (𝑤𝑖𝑡ℎ𝑖𝑛 𝑟𝑒𝑙𝑒𝑣𝑎𝑛𝑡 𝑟𝑎𝑛𝑔𝑒)

𝐻𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑒𝑠𝑡 𝐴𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑡𝑦 − 𝐿𝑜𝑤𝑒𝑠𝑡 𝐴𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑡𝑦

or

𝐶ℎ𝑎𝑛𝑔𝑒 𝑖𝑛 𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑠

𝑉𝑎𝑟𝑖𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑝𝑒𝑟 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡 =

𝐶ℎ𝑎𝑛𝑔𝑒 𝑖𝑛 𝑎𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝑙𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑙

3. Compute the fixed portion of the mixed cost by subtracting the total variable cost from the total mixed costs.

By separating mixed costs into their variable and fixed components and specifying a time period and relevant

range, cost accountants force all costs into variable or fixed categories. Assuming a variable cost is constant

per unit, and a fixed cost is constant in total within the relevant range can be justified for two (2) reasons:

• If a company operates only within the relevant range of activity, the assumed conditions approximate reality,

and thus, the cost assumptions are appropriate; and

• Selection of a constant per-unit variable cost and a constant total fixed cost provides a convenient, stable

measurement for use in planning, controlling, and decision-making activities.

Assuming that the machine hours and electricity costs for ABC Industries for 20CY were as follows:

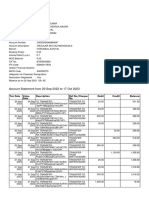

Month Machine Hours Utility Costs

January 2,500 P 36,800

February 2,900 42,000

March 1,900 27,000

April 3,100 46,000

May 3,800 56,500

June 3,300 44,000

July 4,100 49,500

August 3,500 45,500

September 2,000 31,000

October 3,700 52,000

November 4,700 62,000

December 4,200 55,500

1. Select the highest and lowest activity levels and costs (within the relevant range).

Machine Hours Utility Costs

Highest 4,700 P 62,000

Lowest 1,900 27,000

Difference 2,800 P 35,000

2. Compute the variable cost element.

𝐶ℎ𝑎𝑛𝑔𝑒 𝑖𝑛 𝑡𝑜𝑡𝑎𝑙 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡𝑠 𝑃35,000

𝑉𝑎𝑟𝑖𝑎𝑏𝑙𝑒 𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑡 𝑝𝑒𝑟 𝑢𝑛𝑖𝑡 = = = 𝑷𝟏𝟐. 𝟓𝟎 𝒑𝒆𝒓 𝒎𝒂𝒄𝒉𝒊𝒏𝒆 𝒉𝒐𝒖𝒓

𝐶ℎ𝑎𝑛𝑔𝑒 𝑖𝑛 𝑎𝑐𝑡𝑖𝑣𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝑙𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑙 2,800 ℎ𝑜𝑢𝑟𝑠

3. Compute the variable cost at the highest and lowest level of activity.

𝐻𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑒𝑠𝑡 𝐿𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑙 = 4,700 × 𝑃12.50 = 𝑃58,750 𝐿𝑜𝑤𝑒𝑠𝑡 𝐿𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑙 = 1,900 × 𝑃12.50 = 𝑃23,750

4. Determine the fixed cost at each level of activity.

𝐻𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑒𝑠𝑡 𝐿𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑙 = 𝑃62,000 − 𝑃58,750 = 𝑃3,250 𝐿𝑜𝑤𝑒𝑠𝑡 𝐿𝑒𝑣𝑒𝑙 = 𝑃27,000 − 𝑃23,750 = 𝑃3,250

02 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 3 of 10

BM2206

Least Squares Regression Analysis

This statistical technique analyzes the relationship between independent (causal) and dependent (effect)

variables. The least squares method is used to develop an equation that predicts an unknown value of a

dependent variable (cost) from the known values of one or more independent variables (activities that create

costs) (Raiborn & Kinney, 2013).

When multiple independent variables exist, least squares regression also helps select the independent variable

that is the best predictor of the dependent variable. For example, managers can use least squares to decide

whether machine hours, direct labor hours, or pounds of material moved best explain and predict changes in a

specific overhead cost. Simple regression analysis uses one (1) independent variable to predict the dependent

variable based on the y = a + bX formula for a straight line. Two (2) or more independent variables are used to

predict the dependent variable in multiple regression.

Like all mathematical models, regression analysis is based on certain assumptions that produce limitations on

the model’s use. Three (3) of these assumptions follow:

• For regression analysis to be useful, the independent variable must be a valid predictor of the dependent

variable; the relationship can be tested by determining the correlation coefficient.

• Like the high–low method, regression analysis should be used only within a relevant range of activity.

• The regression model is useful only as long as the circumstances existing at its development remain

constant; consequently, if significant additions are made to capacity or if there is a major change in

technology usage, the regression line will no longer be valid.

A regression line is any line that goes through the means (or averages) of the independent and dependent

variables in a set of observations.

The regression line is found by predicting a and b values in a straight line formula using the observations' actual

activity and cost values (y values). The equations necessary to compute a and b values using the method of

least squares are as follows (Raiborn & Kinney, 2013):

Σ𝑥𝑦 − 𝑛(𝑥̅ )(𝑦̅)

𝑏=

Σ𝑥 2 − 𝑛(𝑥̅ )2

𝑎 = 𝑦̅ − 𝑏𝑥̅

Where: 𝑥̅ = mean of the independent variable

𝑦̅ = mean of the dependent variable

𝑛 = number of observations

Using the machine hour and utility cost data for LDR Mechanical (excluding the May outlier), the following

calculations can be made:

Month Machine Hours Utility Costs

January 7,260 P 2,960

February 8,850 3,410

March 4,800 1,920

April 9,000 3,500

May 11,000 3,900 outlier

June 4,900 1,860

July 4,600 2,180

August 8,900 3,470

September 5,900 2,480

October 5,500 2,310

02 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 4 of 10

BM2206

x y xy x2

7,260 P 2,960 P 21,489,600 P 52,707,600

8,850 3,410 30,178,500 78,322,500

4,800 1,920 9,216,000 23,040,000

9,000 3,500 31,500,000 81,000,000

4,900 1,860 9,114,000 24,010,000

4,600 2,180 10,028,000 21,160,000

8,900 3,470 30,883,000 79,210,000

5,900 2,480 14,632,000 34,810,000

5,500 2,310 12,705,000 30,250,000

59,710 P 24,090 P 169,746,100 424,510,100

The mean of x (or 𝑥̅ ) is 6,634.44 (59,710÷9), and the mean of y (or 𝑦̅ ) is P2,676.67 (24,090÷9). Thus,

P169,746,100 − 9(6,634.44)(P2,676.67) 𝑃9,922,241

𝑏= = = 𝑃0.35

424,510,100 − 9(6,634.44)(P2,676.67) 28,367,953

𝑎 = 𝑃2,676.67 − (0.35)(6,634.44) = 𝑃2,676.67 − 2,322.05 = 𝑃354.62

The b (variable cost) and a (fixed cost) values for the company’s utility costs are P0.35 and P354.62, respectively

(Raiborn & Kinney, 2013).

FINANCIAL STATEMENTS CLASSIFICATION

The two (2) basic financial statements are the balance sheet and income statement. The balance sheet is a

statement of unexpired costs (assets), liabilities, and owners’ equity, while the income statement is a statement

of revenues and expired costs (expenses and losses). Matching revenues and expenses on the income

statement is vital to financial accounting. The matching concept provides a basis for deciding when an unexpired

cost becomes an expired cost and is moved from an asset category to an expense or loss category.

There are differences between expenses and losses. Expenses are intentionally incurred in generating

revenues, but losses are unintentionally incurred in business operations. Examples of expenses are the cost of

goods sold, depreciation, and estimated product warranty costs. Costs incurred for damage from a fire,

abnormal production waste, and the sale of a machine at a price below book value are examples of losses.

When a product is the cost object, all costs can be classified as either product or period.

• Product costs are related to making or acquiring the products that directly generate the revenues of an

entity. These are the inputs or resources used to convert raw materials into a finished product.

• Period costs are operating expenses related to business functions other than production, such as selling

and administration. These costs are non-manufacturing costs. These costs are more closely associated

with a particular period than making or acquiring a product.

Product costs are also called inventoriable costs and include direct costs (direct material and direct labor) and

indirect costs (overhead).

• Direct material. Any material that can be easily and economically traced to a product being produced. It

includes raw material, purchased components from contract manufacturers, and manufactured

subassemblies.

02 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 5 of 10

BM2206

• Direct labor. This refers to the time spent by individuals who work specifically on manufacturing a product.

This includes basic pay, cost of living allowance, and 13th month pay and cash equivalents of non-cash

incentives given regularly.

• Overhead. Any production cost that is indirect to the product. It includes factory supervisors’ salaries and

depreciation, insurance, and utility costs on production machinery, equipment, and facilities.

❖ Conversion Cost – sum of direct labor and overhead

❖ Prime Cost – sum of direct materials and direct labor

THE CONVERSION PROCESS

To some extent, all organizations convert inputs into outputs. Inputs typically consist of material, labor, and

overhead. Product costs are generally incurred in the production area, and period costs are incurred in all

nonproduction areas. Products are the usual output of a conversion process.

Firms that engage in only low or moderate conversion degrees can conveniently expense insignificant costs of

labor and overhead related to conversion. The clerical cost savings from expensing outweigh the value of any

slightly improved information that might result from assigning such costs to products. For example, when retail

employees open shipping containers, hang clothing on racks, and tag merchandise with sales tickets, a labor

cost for conversion is incurred. However, clothing stores do not attach the stock workers’ wages to inventory;

such labor costs are treated as period costs and expensed when incurred. The major distinction between retail

firms’ relative manufacturing firms is that retailers have much lower conversion degrees than the other two (2)

types of firms (Raiborn & Kinney, 2013).

In contrast, in high-conversion firms, the informational benefits gained from accumulating the material, labor,

and overhead costs incurred to produce output exceed clerical accumulation costs.

Manufacturing companies are engaged in a high degree of conversion of raw material input into a tangible

output. Manufacturers typically use labor and machines to convert raw material to output that has substance

and can, if desired, be physically inspected (Raiborn & Kinney, 2013).

Retailing and Manufacturing Companies

Retailing companies purchase finished goods or almost finished condition, which typically needs little conversion

before being sold to customers. Costs associated with such inventory are usually easy to determine, as are the

valuations for financial statement presentation. Firms (such as retail stores) that engage in only low or moderate

degrees of conversion ordinarily have only one inventory account (Merchandise Inventory) (Horngen, Datar, &

Rajan, Cost Accounting; A Managerial Emphasis, 2013).

In contrast, companies engaged in transforming physical inputs into finished products are manufacturing

companies. To determine the cost of both inventory produced and goods sold, manufacturers' materials or

supplies and conversion costs are assigned to the output. Cost accounting provides the structure and process

for assigning material and conversion costs to products.

The production or conversion process occurs in three (3) stages:

1. Work not started (raw material),

2. Work started but not completed (work in process), and

3. Work completed (finished goods).

Hence, three (3) inventory accounts are usually used by manufacturers to accumulate costs as goods flow

through the manufacturing process:

1. Raw Material Inventory

2. Work in Process Inventory (for partially converted goods)

3. Finished Goods Inventory

02 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 6 of 10

BM2206

COMPONENTS OF PRODUCT COST

Product costs are related to items that generate a company’s income. These costs can be separated into three

(3) components: direct material, direct labor, and production overhead.

Direct Materials are the materials traceable to the products being produced. However, some material costs are

not conveniently or economically traceable to the final product and are classified as indirect costs (Rante, 2016).

Direct Labor represents compensation and benefits paid to those who physically work on converting raw

materials into finished goods and are easily traceable to a specific process or job order. As with materials, some

labor costs are treated as indirect. One reason for this treatment is that specifically tracing certain labor costs

to production is inefficient. For instance, fringe benefit costs should be treated as direct labor cost. Still, the time,

effort, and clerical expense of tracing this cost might not justify the additional accuracy such tracing would

provide. Thus, the treatment of employee fringe benefits as indirect costs is often based on clerical cost

efficiencies (Rante, 2016).

Factory Overhead is an indirect product cost that includes production costs other than direct materials and

direct labor. These include factory supplies, wages of supervisors, and depreciation of factory plants, among

others. Overhead costs can be variable or fixed based on how they behave in response to changes in production

volume or another activity measure. Variable overhead includes indirect material costs, indirect labor paid on

an hourly basis (such as wages for forklift operators, material handlers, and other workers who support the

production, assembly process), and lubricants used for machine maintenance, and the variable portion of factory

utility charges. Depreciation calculated using either the units-of-production or service-life method is also a

variable overhead cost; these depreciation methods reflect a decline in machine utility based on usage rather

than time passage and are appropriate in an automated plant. Fixed overhead includes costs such as straight-

line depreciation on factory assets, factory license fees, and factory insurance and property taxes. Fixed indirect

labor costs include salaries for production supervisors, shift superintendents, and plant managers. The fixed

portion of factory mixed costs (such as maintenance and utilities) is also part of fixed overhead.

ACCUMULATION AND ALLOCATION OF OVERHEAD

Direct material and direct labor can be easily traced to a product. On the other hand, factory overhead must be

accumulated throughout a period and allocated to the products manufactured during that period.

Cost allocation refers to assigning an indirect cost to one or more cost objects using some reasonable

allocation base or driver. Cost allocations can be made across time periods or within a single time period. For

example, a building’s cost is allocated through depreciation charges over its useful or service life in financial

accounting. This process is necessary to satisfy the matching principle. In cost accounting, production overhead

costs are allocated within a period through allocation bases or cost drivers to products. This process reflects

the application of cost principle, which requires all production or acquisition costs attached to the units produced

or units purchased (Raiborn & Kinney, 2013).

Reasons why overhead costs are allocated to cost objects:

• to determine the full cost of the cost object

• to motivate the manager in charge of the cost object to manage it efficiently

• to compare alternative courses of action for management planning, controlling, and decision making

The first reason relates to the valuation of the financial statement. Under GAAP, a cost object's “full cost” must

include allocated production overhead. In contrast, the assignment of non-manufacturing overhead costs to

products is not normally allowed under GAAP. The other two (2) reasons for overhead allocations are related

to internal purposes, and thus, no specific rules apply to the allocation process. Regardless of why overhead is

allocated, the method and basis of allocation should be rational and systematic so that the resulting information

is useful for product costing and managerial purposes. Traditionally, the information generated for satisfying the

“full cost” objective was also used for the second and third objectives. However, because the first purpose is

externally focused and the others are internally focused, different methods can be used to provide different

costs for different needs (Raiborn & Kinney, 2013).

02 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 7 of 10

BM2206

One way of allocating overhead to products is actual cost system. This system accumulates actual direct

material and direct labor to Work in Process (WIP) Inventory as incurred costs. Actual production overhead

costs are accumulated separately in an Overhead Control account. They are assigned to WIP Inventory either

at the end of a period or after production. Using an actual cost system is impractical because all production

overhead information must be available before any cost allocation can be made to products or services. For

example, the cost of products manufactured in May could not be calculated until the May electricity bill is

received in June.

Another way of allocating overhead to products is the normal cost system. This system combines direct

material and direct labor actual costs with the overhead assigned using a predetermined rate/s. A

predetermined overhead rate (or overhead application rate) is a charge per unit of activity that is used to

allocate overhead cost from the Overhead Control account to Work in Process Inventory for the period’s

production. Accumulation of product costs can be either perpetual inventory system or a periodic inventory

system.

Perpetual Inventory System. This system requires maintaining stock cards for each type of raw material to

show the summary of the inflow, outflow, and balance of raw materials in quantity. In this system, all product

costs flow through Work in Process (WIP) Inventory to Finished Goods (FG) Inventory and, finally, to Cost of

Goods Sold (CGS). The perpetual inventory system continuously provides information for financial statement

preparation and inventory and cost control. Because the cost of maintaining a perpetual system has diminished

significantly as computerized production, barcoding, and information processing have become more general,

the discussion assumes that most companies use a perpetual system.

Periodic Inventory System. Under this system, there is no need to maintain a stock card for the raw materials.

A physical count is made periodically near the end of a period to determine the units on hand. The latest

purchases are normally left in the warehouse. The raw materials issued are the residual amount after deducting

the physical inventory counted from goods available for sale.

Example: The MLDR Corporation illustrates the flow of product costs in a manufacturing company’s actual cost

system. The April 1, 20CY, inventory account balances for the company were as follows:

• Raw Materials (RM) Inventory (all direct), P73,000

• Work in Process (WIP) Inventory, P145,000

• Finished Goods (FG) Inventory, P87,400

Mac Corporation uses separate variable and fixed accounts to record overhead costs. In this example, actual

overhead costs are used to allocate overhead to WIP Inventory. During the month, Mac’s purchasing agent

bought P280,000 of direct materials on the account, and the warehouse manager transferred P284,000 of direct

materials to the production area.

1. Raw Materials Inventory P280,000

Accounts Payable P280,000

To record cost of raw material purchased on account

2. Work in Process Inventory P284,000

Raw Materials Inventory P284,000

To record raw materials transferred to production

April’s production wages totaled P530,000, of which P436,000 was for direct labor.

3. Work in Process Inventory P436,000

Variable Overhead Control 94,000

Salaries Payable P530,000

To accrue factory wages for direct and indirect labor

April salaries for the production supervisors were P20,000.

02 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 8 of 10

BM2206

4. Fixed Overhead Control P20,000

Salaries Payable P20,000

To accrue production supervisors’ salaries

April utility cost of P28,000 was accrued; an analysis of this cost indicated that P16,000 was variable and P2,000

was fixed.

5. Variable Overhead Control P16,000

Fixed Overhead Control 12,000

Utilities Payable P28,000

To record mixed utility costs in its variable and fixed amounts

Supplies costing P5,200 were removed from inventory and used in production.

6. Variable Overhead Control P5,200

Supplies Inventory P5,200

To record supplies used

MLDR Corporation paid P7,000 for April’s property taxes on the factory, depreciated the factory assets P56,880,

and recorded the expiration of P3,000 of prepaid insurance on the factory assets.

7. Fixed Overhead Control P7,000

Cash P7,000

To record payment for factory property taxes for the period

8. Fixed Overhead Control P56,880

Accumulated Depreciation - Equipment P56,880

To record depreciation on factory assets for the period

9. Fixed Overhead Control P3,000

Prepaid Insurance P3,000

To record the expiration of prepaid insurance on factory assets

The actual overhead cost was assigned to WIP Inventory for April. During the month, P1,058,200 of goods were

completed and transferred to FG Inventory.

10. Work in Process Inventory P214,080

Variable Overhead Control P115,200

Fixed Overhead Control 98,880

To record the assignment of actual overhead costs to WIP Inventory

11. Finished Goods Inventory P1,058,200

Work in Process Inventory P1,058,200

To record the transfer of work completed during the period

Total April sales were P1,460,000, and these were all on account; goods that were sold had a total cost of

P1,054,000.

12. Accounts Receivable P1,460,000

Sales P1,460,000

To record total sales of goods sold on account during the period

13. Cost of Goods Sold P1,054,000

Finished Goods Inventory P1,054,000

To record the cost of goods sold for the period

02 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 9 of 10

BM2206

COST OF GOODS MANUFACTURED AND SOLD

The T-accounts provide detailed information about the cost of material used, goods transferred from work in

process, and goods sold. This information is needed to prepare the financial statements. As a preliminary step,

a schedule of cost of goods manufactured is prepared to determine the cost of goods sold. The cost of goods

manufactured (CGM) is the total production cost of the completed goods and transferred to FG Inventory during

the period. The schedule of cost of goods manufactured starts with several direct materials (DM) used. This

cost in production during the period is equal to the beginning balance of RM Inventory plus raw material

purchased and minus the ending balance of RM Inventory. Suppose RM Inventory includes both direct and

indirect materials. In that case, the cost of direct material used is assigned to WIP Inventory and the cost of

indirect material used is included in variable overhead. Because direct labor cannot be warehoused, all charges

for direct labor during the period are part of WIP Inventory. Variable and fixed overhead costs are added to

direct material and direct labor costs to determine total manufacturing costs. Beginning WIP Inventory cost is

added to total current manufacturing costs to obtain a subtotal amount referred to as the total cost of goods

placed into the process. The value of the ending WIP Inventory is calculated and subtracted from the subtotal

to provide the cost of goods manufactured (COGM) for the period. To compute the cost of goods sold, the

COGM is added to the beginning balance of FG Inventory to find the cost of goods available for sale (COGAS)

during the period. Ending FG Inventory is calculated by multiplying a physical unit count times a unit cost. If a

perpetual inventory system is used, the actual amount of ending FG Inventory can be compared to the amount

shown in the accounting records. Any differences can be attributed to losses that could have arisen from theft,

breakage, evaporation, or accounting errors. Ending FG Inventory is subtracted from the cost of goods available

for sale to determine the cost of goods sold (COGS).

References:

De Leon, N. D., & De Leon, Jr., G. M. (2014). Cost accounting. Manila CIty: GIC Enterprises & Co., Inc.

Guerrero, P. (2015). Cost accounting: Principles and procedural applications, 2014-2015 Edition. GIC

Enterprises and Co. Inc.

Horngen, C. T., Datar, S. M., & Rajan, M. (2013). Cost accounting: A managerial emphasis. Pearson Prentice

Hall.

Raiborn, C. A., & Kinney, M. R. (2013). Cost accounting. Cengage Learning Asia Pte Ltd (Philippine Branch).

Rante, G. A. (2016). Cost accounting. Millenium Books, Inc.

02 Handout 1 *Property of STI

student.feedback@sti.edu Page 10 of 10

You might also like

- Cost Analysis of Amul CompanyDocument6 pagesCost Analysis of Amul Companyniravpatel1370% (10)

- Report On Cost EstimationDocument41 pagesReport On Cost EstimationTuhin SamirNo ratings yet

- Lesson 1-3 Cost Behavior: Analysis and UseDocument15 pagesLesson 1-3 Cost Behavior: Analysis and UseClaire Barba50% (2)

- Cost-Ii CH-3 &4Document108 pagesCost-Ii CH-3 &4Hayelom Tadesse GebreNo ratings yet

- Marketing Management RDocument14 pagesMarketing Management Rmayankk1387_82346053No ratings yet

- CA&C 02 - Handout - 1 PDFDocument10 pagesCA&C 02 - Handout - 1 PDFMelchie RepospoloNo ratings yet

- COST ACCOUNTING - Cost Concepts and ClassificationDocument18 pagesCOST ACCOUNTING - Cost Concepts and ClassificationJustine Reine CornicoNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER I Lecture NoteDocument12 pagesCHAPTER I Lecture NotegereNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER I Lecture NoteDocument20 pagesCHAPTER I Lecture NotegereNo ratings yet

- CHAPTER I Lecture NoteDocument17 pagesCHAPTER I Lecture NoteKalkidan NigussieNo ratings yet

- Class 2-Fundamental ConceptsDocument29 pagesClass 2-Fundamental ConceptsLamethysteNo ratings yet

- Unit 2 Sessions 1, 2 & 3Document78 pagesUnit 2 Sessions 1, 2 & 3Dr. M. SamyNo ratings yet

- Decision Making Through Marginal CostingDocument33 pagesDecision Making Through Marginal CostingKanika Chhabra100% (2)

- Marginal Costing With Decision MakingDocument38 pagesMarginal Costing With Decision MakingHaresh Sahitya0% (1)

- Marginal CostingDocument37 pagesMarginal Costingbhavinpoldiya100% (1)

- Cost & Management Accounting April 2022 ExaminationDocument10 pagesCost & Management Accounting April 2022 ExaminationNageshwar SinghNo ratings yet

- COST TERMS, CON-WPS OfficeDocument3 pagesCOST TERMS, CON-WPS OfficeRafols AnnabelleNo ratings yet

- Accounting 202 Exam 1 Study Guide: Chapter 1: Managerial Accounting and Cost Concepts (12 Questions)Document4 pagesAccounting 202 Exam 1 Study Guide: Chapter 1: Managerial Accounting and Cost Concepts (12 Questions)zoedmoleNo ratings yet

- Chapter 3 Partnership AccountingDocument7 pagesChapter 3 Partnership AccountingMae Zenica VirtusNo ratings yet

- Cost IIiiiiiDocument77 pagesCost IIiiiiiKiya AbdiNo ratings yet

- What Do You Mean by OverheadsDocument6 pagesWhat Do You Mean by OverheadsNimish KumarNo ratings yet

- Predetermined Overhead Rates, Flexible Budgets, and Absorption/Variable Costing QuestionsDocument4 pagesPredetermined Overhead Rates, Flexible Budgets, and Absorption/Variable Costing QuestionsSomething ChicNo ratings yet

- Marginal Costing and Absorption CostingDocument12 pagesMarginal Costing and Absorption CostingStili MwasileNo ratings yet

- Cost Accounting REVIEWERDocument4 pagesCost Accounting REVIEWERMelissa SenonNo ratings yet

- Cost and Mgmt. Acctg. Ch. 2 and 4Document30 pagesCost and Mgmt. Acctg. Ch. 2 and 4s.gallur.gwynethNo ratings yet

- Pre-Study Session 4Document10 pagesPre-Study Session 4Narendralaxman ReddyNo ratings yet

- FIN600 Module 3 Notes - Financial Management Accounting ConceptsDocument20 pagesFIN600 Module 3 Notes - Financial Management Accounting ConceptsInés Tetuá TralleroNo ratings yet

- Learning ObjectivesDocument10 pagesLearning ObjectivesShraddha MalandkarNo ratings yet

- Cost Concepts, Cost Analysis, and Cost EstimationDocument2 pagesCost Concepts, Cost Analysis, and Cost EstimationGêmTürÏngånÖNo ratings yet

- Marginal CostingDocument14 pagesMarginal CostingVijay DangwaniNo ratings yet

- Full Cost AccountingDocument27 pagesFull Cost AccountingMarjorie OndevillaNo ratings yet

- Cost and Management Accounting Sem3Document11 pagesCost and Management Accounting Sem3saurabhnanda14No ratings yet

- Costing For A Spinning MillDocument14 pagesCosting For A Spinning Millvijay100% (1)

- Dominic AssignmentDocument2 pagesDominic Assignmentmarkzugg9No ratings yet

- Distinguish Between Marginal Costing and Absorption CostingDocument10 pagesDistinguish Between Marginal Costing and Absorption Costingmohamed Suhuraab50% (2)

- 1.2.1 Cost-Terms-Concepts-And-BehaviorDocument4 pages1.2.1 Cost-Terms-Concepts-And-Behaviorro1cristy22No ratings yet

- Esther AssignmentDocument12 pagesEsther AssignmenthazonmalachiNo ratings yet

- Marginal Costing - DefinitionDocument15 pagesMarginal Costing - DefinitionShivani JainNo ratings yet

- What Is The Difference Between Marginal Costing and Absorption Costing Only HeadingsDocument10 pagesWhat Is The Difference Between Marginal Costing and Absorption Costing Only HeadingsLucky ChaudhryNo ratings yet

- Cost Classification and Terminologies Harambe University CollegeDocument12 pagesCost Classification and Terminologies Harambe University Collegeአረጋዊ ሐይለማርያምNo ratings yet

- Marginal CostingDocument42 pagesMarginal CostingAbdifatah SaidNo ratings yet

- Costing For A Spinning Mill PDFDocument13 pagesCosting For A Spinning Mill PDFyogesh kumawatNo ratings yet

- Esther AssinmentDocument10 pagesEsther AssinmenthazonmalachiNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2 AccDocument5 pagesChapter 2 AccMarta Fdez-FournierNo ratings yet

- Chapter 12 Marginal CostingDocument40 pagesChapter 12 Marginal CostingAli AbdurahimanNo ratings yet

- Marginal Costing: 12.1 DefinitionsDocument41 pagesMarginal Costing: 12.1 DefinitionsRohit RoyNo ratings yet

- Tong Hop Kien ThucDocument13 pagesTong Hop Kien ThucCloudSpireNo ratings yet

- Classification of Cost. (ODA, ODAIT, ODFB&ODEF)Document4 pagesClassification of Cost. (ODA, ODAIT, ODFB&ODEF)rofoba6609No ratings yet

- Accounting For Factory OverheadDocument21 pagesAccounting For Factory OverheadMirante DalapaNo ratings yet

- Module 9 LectureDocument19 pagesModule 9 Lecturejustine reine cornico100% (4)

- MarginalCosting Unit 5Document13 pagesMarginalCosting Unit 5sourabhdangarhNo ratings yet

- Managerial AccountingDocument10 pagesManagerial AccountingM HABIBULLAHNo ratings yet

- Chapter 4 DiscussionDocument11 pagesChapter 4 DiscussionArah OpalecNo ratings yet

- 01 Cost Concepts and Behavior.docxDocument6 pages01 Cost Concepts and Behavior.docxjosh.tanNo ratings yet

- Marginal Costing PDFDocument26 pagesMarginal Costing PDFMasumiNo ratings yet

- On Target Vol2 No4 2012 SEP Overhead Rates and Absorption Versus Variable CostingDocument6 pagesOn Target Vol2 No4 2012 SEP Overhead Rates and Absorption Versus Variable CostingnajmulNo ratings yet

- Costing and Pricing Summary Reviewer Chapter 1 To 3Document6 pagesCosting and Pricing Summary Reviewer Chapter 1 To 3Ralph AbutinNo ratings yet

- Ch3 Raiborn SMDocument34 pagesCh3 Raiborn SMOwdray Cia100% (1)

- Finance for Non-Financiers 2: Professional FinancesFrom EverandFinance for Non-Financiers 2: Professional FinancesNo ratings yet

- 03 Activity 2 (7) - 1Document2 pages03 Activity 2 (7) - 1Adrasteia ZachryNo ratings yet

- 03 Handout 1Document7 pages03 Handout 1Adrasteia ZachryNo ratings yet

- 01 Task Performance 12Document3 pages01 Task Performance 12Adrasteia ZachryNo ratings yet

- Fajardo IntmgtAcctg3Exer3Document6 pagesFajardo IntmgtAcctg3Exer3Adrasteia ZachryNo ratings yet

- BM2008 Syllabus and Course OutlineDocument5 pagesBM2008 Syllabus and Course OutlineAdrasteia ZachryNo ratings yet

- 04 Handout 1Document3 pages04 Handout 1Adrasteia ZachryNo ratings yet

- 04 Laboratory Exercise STAT PDFDocument4 pages04 Laboratory Exercise STAT PDFAdrasteia Zachry100% (1)

- Module 13. Restrictive and Unfair Trade PracticesDocument8 pagesModule 13. Restrictive and Unfair Trade PracticesGuenn SarmientoNo ratings yet

- Bid Submission Requirements ElectricalDocument1 pageBid Submission Requirements Electricalnyala chisolaNo ratings yet

- Induction of AllegroDocument21 pagesInduction of AllegroB.n. GurjarNo ratings yet

- ZSPL Bszu BWUU1 Z HODocument13 pagesZSPL Bszu BWUU1 Z HORakesh BabuNo ratings yet

- Audit Questionnaire 888Document9 pagesAudit Questionnaire 888Sheenee VillariasNo ratings yet

- ShivamDocument40 pagesShivamNitesh TiwariNo ratings yet

- Seec ConsultantsDocument1 pageSeec ConsultantsThota SathvikNo ratings yet

- Chap 003Document72 pagesChap 003Hà PhươngNo ratings yet

- Team Salt WBDocument29 pagesTeam Salt WBSholley MatuiNo ratings yet

- Car For Sale: A. Here Are Some More Car Ads. Read Them and Complete The Answers BelowDocument5 pagesCar For Sale: A. Here Are Some More Car Ads. Read Them and Complete The Answers BelowCésar Cordova DíazNo ratings yet

- Talent Placement Companies of EduClaas - 1 Sep 2022Document57 pagesTalent Placement Companies of EduClaas - 1 Sep 2022MimyNo ratings yet

- 202 Priya ShouganiDocument68 pages202 Priya ShouganiSHANTANU DHAVALENo ratings yet

- Approval - Dhrub Nath Pandey-5067Document9 pagesApproval - Dhrub Nath Pandey-5067api-27120082No ratings yet

- Selina Madikana MakhuraDocument9 pagesSelina Madikana Makhuraselinamakhura481No ratings yet

- Mitesh BiographyDocument12 pagesMitesh BiographyRaghavendra Rao TNo ratings yet

- Partnership Liquidation Name: Date: Professor: Section: Score: QuizDocument3 pagesPartnership Liquidation Name: Date: Professor: Section: Score: QuizKimberly Quin CañasNo ratings yet

- Company Profile StainlessDocument12 pagesCompany Profile Stainlessmompuchi482No ratings yet

- AFAR - Until Conso FS HeyheiDocument31 pagesAFAR - Until Conso FS Heyheimisonim.eNo ratings yet

- Synopsis of Effect of Non Registration of The Partnership FirmDocument6 pagesSynopsis of Effect of Non Registration of The Partnership FirmVishesh KumarNo ratings yet

- I. Comprehension: Answer These Questions BrieflyDocument2 pagesI. Comprehension: Answer These Questions BrieflyNabila Puspita PutriNo ratings yet

- REO Local Taxation PDFDocument19 pagesREO Local Taxation PDFcaringalrhonamae48No ratings yet

- EntrepreneurshipDocument6 pagesEntrepreneurshipJean Rose GentizonNo ratings yet

- 03a Time Value of Money Part 2 Test Bank Problems Solutions 2018 0129 12Document57 pages03a Time Value of Money Part 2 Test Bank Problems Solutions 2018 0129 12Jessica AlbaracinNo ratings yet

- Week 7 AUDIT PreTestDocument19 pagesWeek 7 AUDIT PreTestCale HenituseNo ratings yet

- Project ManagementDocument87 pagesProject ManagementLinaNo ratings yet

- Directors ReportDocument16 pagesDirectors ReportvineminaiNo ratings yet

- How To Choose A Lead Qualification Framework? 7 Examples To Pick FromDocument16 pagesHow To Choose A Lead Qualification Framework? 7 Examples To Pick FromLukas ArenasNo ratings yet

- Business Letter AssignmentDocument5 pagesBusiness Letter AssignmentkasnanwlfNo ratings yet