Latour - Bruno - 2014 - Agency at The Time of The Anthropocene

Latour - Bruno - 2014 - Agency at The Time of The Anthropocene

Uploaded by

Nicole KastaniasCopyright:

Available Formats

Latour - Bruno - 2014 - Agency at The Time of The Anthropocene

Latour - Bruno - 2014 - Agency at The Time of The Anthropocene

Uploaded by

Nicole KastaniasOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Latour - Bruno - 2014 - Agency at The Time of The Anthropocene

Latour - Bruno - 2014 - Agency at The Time of The Anthropocene

Uploaded by

Nicole KastaniasCopyright:

Available Formats

Agency at the Time of the Anthropocene

Author(s): Bruno Latour

Source: New Literary History , WINTER 2014, Vol. 45, No. 1 (WINTER 2014), pp. 1-18

Published by: The Johns Hopkins University Press

Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/24542578

JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide

range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and

facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.

Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at

https://about.jstor.org/terms

The Johns Hopkins University Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and

extend access to New Literary History

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

Agency at the Time of the Anthropocene

Bruno Latour

Et pourtant la Terre s'émeut

—Michel Serres, Le contrat naturel

news like this one from Le Monde on Tuesday, May 7, 2013:

How are"Atwe

Maunasupposed

Loa, on Friday to

May react when faced

3, the concentration of COs with a piece of

was reaching 399.29 ppm"? How can we absorb the odd novelty of the

headline: 'The amount of C02 in the air is the highest it has been for

more than 2.5 million years—the threshold of 400 ppm of C02, the

main agent of global warming, is going to be crossed this year"? Such an

extension of both the span of deep history and the impact of our own

collective action is made even more troubling by the subtitle in the same

article, which quietly states: 'The maximum permissible COs limit was

crossed just before 1990." So not only do we have to swallow the news

that our very recent development has modified a state of affairs that is

vastly older than the very existence of the human race (a diagram in the

article reminds us that the oldest human tools are comparatively very

recent!), but we have also to absorb the disturbing fact that the drama

has been completed and that the main revolutionary event is behind us,

since we have already crossed a few of the nine "planetary boundaries"

considered by some scientists as the ultimate barrier not to overstep!1

I think that it is easy for us to agree that, in modernism, people are

not equipped with the mental and emotional repertoire to deal with

such a vast scale of events; that they have difficulty submitting to such

a rapid acceleration for which, in addition, they are supposed to feel

responsible while, in the meantime, this call for action has none of the

traits of their older revolutionary dreams. How can we simultaneously

be part of such a long history, have such an important influence, and

yet be so late in realizing what has happened and so utterly impotent

in our attempts to fix it?

What I find amazing in such a piece of news is, first, the number of

scientific disciplines involved in producing the set of figures that the

journalist uses—from climatology to paleontology—and second, the

historical drama in which those sciences are, from now on, so deeply

New Literary History, 2014, 45: 1-18

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NEW LITERARY HISTORY

entangled. It is impossible to read such a statemen

fact" contemplated coldly from a distant place, as wa

the case, in earlier times, when dealing with "information

the "natural sciences." There is no distant place anym

with distance, objectivity is gone as well, or at least a

objectivity that was unable to take into account the

history. No wonder that climatosceptics are denying th

those "facts" that they now put in scare quotes. In a w

not because all those disciplines are not producing an

resist objections (that's where objectivity really comes fro

the very notion of objectivity has been totally subverted

of humans in the phenomena to be described—and in

tackling them.2

While the older problem of science studies was to under

role of scientists in the construction of facts, a new pr

to understand the active role of human agency not onl

tion of facts, but also in the very existence of the phenom

are trying to document? The many important nuanc

news, stories, alarms, warnings, norms, and duties are

is why it is so important to try to clarify a few of them

when we are trying to understand how we could shift

to ecology, given the old connection between those tw

the "scientific worldview."

At the beginning of the 1990s, just at the time when the dangerous

C02 threshold had been unwittingly crossed, the French philosopher

Michel Serres, in a daring and idiosyncratic book called The Natural

Contract, offered, among many innovative ideas, a fictional reenactment

of Galileo's most famous quote: "Eppur si muove\" In the potted history

of science that we all learned at school, after having been forbidden by

the Holy Inquisition to teach anything publically about the movement

of the Earth, Galileo is supposed to have mumbled "and yet it moves."

This episode is what Serres calls the first trial: a "prophetic" scientist

pitted against all the authorities of the time, stating silently the objec

tive fact that will later destroy these authorities. But now, according to

Serres, we are witnessing a second trial: in front of all the assembled

powers, another scientist—or rather an assembly of equally "prophetic"

scientists—is condemned to remain silent by all those who are in denial

about the behavior of the Earth, and he mumbles the same "Eppur si

muove" by giving it a different and rather terrifying new spin: "andyet the

Earth is moved." (The French is even more telling: "Et pourtant la Terre

se meut' versus "et pourtant la Terre s'émeut"\) Serres writes:

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AGENCY AT THE TIME OF THE ANTHROPOCENE

Science won all the rights three centuries ago now, by appealing t

which responded by moving. So the prophet became king. In our

appealing to an absent authority, when we cry, like Galileo, but befo

of his successors, former prophets turned kings: "the Earth is mo

memorial, fixed Earth, which provided the conditions and founda

lives, is moving, the fundamental Earth is trembling.3

In an academic setting, I don't need to review those new

with which the Earth is now agitated in addition to its usua

Not only does it turn around the Sun (that much we knew

agitated through the highly complex workings of many enmesh

organisms, the whole of which is either called "Earth system sc

more radically, Gaia.4 Gaia, a very ticklish sort of goddess.

ries after the facts of astronomy, facts of geology have become

much so that a piece of information about Charles David Re

at Mauna Loa has shifted from the "science and technology

the newspaper to a new section reserved for the damning t

the Earth.5 We all agree that, far from being a Galilean bod

of any other movements than those of billiard balls, the Ear

taken back all the characteristics of a full-fledged actor. In

pesh Chakrabarty has proposed, it has become once again a

history, or rather, an agent of what I have proposed to call our

geostory.6 The problem for all of us in philosophy, science, or

becomes: how do we tell such a story?

We should not be surprised that a new form of agency—"it is

is just as surprising to the established powers as the old on

moving." If the Inquisition was shocked at the news that th

nothing more than a billiard ball spinning endlessly in the v

(remember the scene where Bertolt Brecht has the monks a

ridicule Galileo's heliocentrism by whirling aimlessly in a r

Vatican),7 the new Inquisition (now economic rather than

shocked to learn that the Earth has become—has become a

tive, local, limited, sensitive, fragile, quaking, and easily tickled

We would need a new Bertolt Brecht to depict how, on talk

on Fox News, so many people (for instance, the Koch brot

physicists, a lot of intellectuals, a great many politicians fr

right, and alas quite a few cardinals and pastors) are now rid

discovery of the new—also very old—agitated and sensitive Eart

point of being in denial about this large body of science.

In order to portray the first new Earth as one falling bo

all the other falling bodies of the universe, Galileo had to p

notions of climate, agitation, and metamorphosis (apart from

discover the second new Earth, climatologists are bringing

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NEW LITERARY HISTORY

back in and returning the Earth to its sublunar, corru

condition. Galileo's Earth could spin, but it had no "t

no "planetary boundaries." As Michael Hulme has said

means to talk again not about "the weather," but abo

as a new form of discourse.9 The European prescienti

Earth saw it as a cesspool of decay, death, and corrup

our ancestors, their eyes fixed toward the incorruptibl

stars, and God, had a tiny chance of escaping solely t

contemplation, and knowledge; today, in a sort of co

revolution, it is science that is forcing our eyes to turn t

considered, once again, as a cesspool of conflict, deca

and corruption. This time, however, there is no praye

of escaping to anywhere else. After having moved fro

mos to the infinite universe,10 we have to move back

universe to the closed cosmos—except this time ther

God, no hierarchy, no authority, and thus literally no

that means a handsome and well-composed, arrangeme

new situation its Greek name, kakosmos. What a drama

through: from cosmos to the universe and then, from

the kakosmos\ Enough of a move to make us feel que

Mrs. Sarti in Brecht's play.

Even though we have to continue fighting those who

propose that we let them alone for a moment and seize

to advance our common cosmopolitics.11 What I want

paper is what sort of agency this new Earth should b

other insights from Serres will render my goal clearer

passage I quoted, he reverses the distribution of "subje

understood here in their legal sense. ( The Natural Contrac

a piece of legal philosophy.)

For, as of today, the Earth is quaking anew: not because it

its restless, wise orbit, not because it is changing, from its d

velope of air, but because it is being transformed by our doing

reference point for ancient law and for modern science becaus

objectivity in the legal sense, as in the scientific sense, ema

urithout man, which did not depend on us and on which w

and de facto. Yet henceforth it depends so much on us that it

we too are worried by this deviation from expected equilibria.

the Earth and making it quake! Now it has a subject once again

Although the book does not invoke the name of "Gaia" a

before the label "Anthropocene" became so widesprea

it points to the same complete subversion of the respe

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AGENCY AT THE TIME OF THE ANTHROPOCENE

subject and object. Since the scientific revolution, the ob

world without humans had offered a solid ground for a sort

jus naturalism—if not for religion and morality, at least

law. At the time of the counter-Copernican revolution, w

toward the former solid ground of natural law, what do

traces of our action are visible everywhere! And not in

that the Male Western Subject dominated the wild and sa

nature through His courageous, violent, sometimes hubr

control. No, this time we encounter, just as in the old pr

nonmodern myths,13 an agent which gains its name of "s

he or she might be subjected to the vagaries, bad humor,

tions, and even revenge of another agent, who also gains

"subject" because it is also subjected, to his or her action. It is

sense that humans are no longer submitted to the diktat

nature, since what comes to them is also an intensively s

of action. To be a subject is not to act autonomously in

objective background, but to share agency with other subject

lost their autonomy. It is because we are now confronted

jects—or rather c/îta.vi-subject.s—that we have to shift away

of mastery as well as from the threat of being fully natu

without bifurcation between object and subject; Hegel wit

Spirit; Marx without dialectics. But it is also in another radic

the Earth is no longer "objective"; it cannot be put at a

emptied of all Its humans. Human action is visible every

construction of knowledge as well as in the production of th

those sciences are called to register.

What seems impossible, however, in Serres's solution i

idea of establishing a new social compact with all those

Not that the idea of a contract is odd (contrary to many

proposition), but because in a quarter of a century, thing

so urgent and violent that the somewhat pacific project

among parties seems unreachable. War is infinitely mor

contract. Or else we will have to appeal to another body o

civil law to penal law. Words such as symbiosis, harmony, agr

all those ideals of deep ecology smack of an earlier, less b

Since then everything has taken a turn for the worse. T

hope for is to stick to a new sort of jus gentium that wo

against one another and against what James Lovelock h

revenge of Gaia."15 As Isabelle Stengers puts it, now the task

try to "protect us."16 The new subjects subjected to the vaga

own interconnected collisions are not trying to negotia

but to engage in a sort of parley much more primitive th

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NEW LITERARY HISTORY

place or the court of law. No time for commerce. No

oaths. Contrary to Hobbes's scheme, the "state of natu

a dangerous tendency to follow, and not to precede o

the time of the civil compact. In twenty-three years,

zation has regressed so much that Serres's stopgap so

mind a strange form of nostalgia: yes, at the time, it

to dream of making a "contract with nature." But Gaia

altogether—maybe also a different sovereign,17

So, to profit from Serres's insight freed from his le

have to dig a bit deeper and detect how the different

mobilized in geostory might be able to swap the vari

fine their agencies. "Trait" is precisely the technical w

law, geopolitics, science, architecture, and geometry t

designate this trading zone between former objects and

Moreover the word trait, in French, like draft in English, mea

bond and the basic stroke of writing: dot and long mark, a

written contract obligates and ties those who write their na

its clauses. . . . Now the first great scientific system, Newton'

by attraction: there's the same word again, the same trait, the sam

planetary bodies grasp or comprehend one another and are bound

but a law that is the spitting image of a contract, in the primary

cords. The slightest movement of any one planet has imme

the others, whose reactions act unhindered on the first. T

constraints, the Earth comprehends, in a way, the point of view

since it must reverberate with the events of the whole system

How extraordinary to claim that the best example of a

is Newton's law of gravitation! How can you drag Newton'

an anthropocentric argument about "points of view" and "

There is nobody there to "see" and to "interpret" anyt

just the type of slippage from one language game to

made Serres's anthropology of science so open to crit

generally, that have subjected the humanities to so m

problem, of course, is to do justice to this sentence w

simply as a clever metaphor. To move on we have to

to clearly understand the conditions under which it co

more than an image.

Thanks to a magnificent paper by Simon Schaffer,19

remember that Newton himself had to generate out o

a set of traits for the new agent that came to be know

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AGENCY AT THE TIME OF THE ANTHROPOCENE

To be sure, it was not anthropomorphic, but rather ange

combat Cartesian tourbillons, Newton had to think of an

transport action at a distance instantaneously. At the time, t

character available to him that could be entrusted with t

tion of instantaneous movement, except angels... Hundre

angelology later, Newton could progressively clip their w

form this new agent into a "force." A "purely objective"

but still powered, from behind, by thousands of years of

an angelic "instant messaging system." Purity is not what sc

of: behind the force, the wings of angels are still invisibl

As the whole history of science—and Serres himself for a l

his earlier work—has often shown, it is difficult to follow t

of scientific concepts without taking into account the vas

ground that allows scientists to first animate them, and

later, to deanimate them. Although the official philosophy o

the latter movement as the only important and rationa

opposite is true: animation is the essential phenomenon;

a superficial, ancillary, polemical, and more often than n

one.20 One of the main puzzles of Western history is not tha

people who still believe in animism," but the rather nai

many still have in a deanimated world of mere stuff; just at

when they themselves multiply the agencies with which

deeply entangled every day. The more we move in geosto

this belief seems difficult to understand.

There are at least two ways, one from semiotics and the other from

ontology, to direct our attention to the common ground of agency be

fore we let it bifurcate into what is animated and what is deanimated.

Let's try semiotics first.

In novels, readers have no difficulty in detecting the great number of

contradictory actions with which characters are simultaneously endowed.

Witness, for instance, in this famous passage of Tolstoy's War and Peace,

Prince Kutuzov's decision to finally get into action:

The Cossack's report, confirmed by horse patrols who were sent out, was the

final proof that events had matured. The tighdy coiled spring was released, the

clock began to whirr and the chimes to play. Despite all his supposed power, his

intellect, his experience, and his knowledge of men, Kutuzov—having taken into

consideration the Cossack's report, a note from Bennigsen who sent personal

reports to the Emperor, the wishes he supposed the Emperor to hold, and

the fact that all the generals expressed the same wish—could no longer check the

inevitable movement, and gave the order to do what he regarded as useless and

harmful—gave his approval, that is, to the accomplished fact}1

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

NEW LITERARY HISTORY

If we are here miles away from the idea of a supr

mastering his decisions as a rational subject, neither is

fact" forcing Kutuzov as if he were a passive object. In

agricultural metaphor ("events have matured') followe

chanical one ("the clock began to play'), many other ele

taken into account: a highly doubtful dispatch from a

against him by his own aide-de-camp, the gentle pressu

as well as his own tentative interpretation of the Emp

in the end, the movement "is inevitable," the supreme

though he regards it "as useless and harmful," "gave th

his approval." (As readers of the novel will remember

remainder of the passage, will do everything to delay

which nonetheless he will win in the end because he has succeeded in

doing next to nothing against the agitated marches and countermarches

of Napoleon's Great Army!)

If we tend to find this nondecision by a supreme commander so real

istic, it is precisely because the author mixes up all the traits that could

allow us to distinguish objects and subjects—"accomplished facts" and

"inevitable movement" on the one hand and, on the other, "power, intellect,

experience, and knowledge. " Great novels disseminate the sources of actions

in a way that the official philosophy available at their time is unable to

follow. There is here a more general lesson to be drawn. What makes

the Moderns so puzzling for an anthropologist is that there is never

any resemblance in the traits attributed to objectivity and subjectivity

and the reality of their distribution. This is what allowed me to say that

"we have never been modern."22 At the time of the Anthropocene, with

its utter confusion between objects and subjects, it is probable that the

reading of Tolstoy would do a great deal of good for the geoengineers

portrayed in Clive Hamilton's frightening new book, in which he reviews

the many schemes to save the planet, each crazier than the next.23 Given

that those who believe they will be in command—those whom Hamilton

calls Earthmasters—will never control things better than Kutuzov, if we

give them the Earth, what a mess they'll make of it!

You might object that novelists are paid to fathom the folds of the

human soul, and that it is no wonder they are able to complicate what

philosophers would instead prefer to clarify. And it is true that in Kutu

zov's example, there is no agent that would count as a real natural force.

In spite of the mechanical metaphors, we remain among humans. But

let me take now an example from a bestseller with the very modernist

title: The Control of Nature?* John McPhee's document is a remarkable set

of stories about how heroic humans are dealing with invincible natural

agents—water, landslides, and volcanoes. What interests me here are

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AGENCY AT THE TIME OF THE ANTHROPOCENE

the two literal trade-offs between, on one side, two rivers, t

and the Atchafalaya, and on the other, those two compet

a human agency, the US Army Corps of Engineers.

The situation McPhee describes is the following: if the M

tinues flowing east of New Orleans, it is thanks to a singl

upstream at a small bend of the river, that protects the gian

its capture by the much smaller, but unfortunately much lo

of the Atchafalaya. If this dam were to be breached (the

every year), the whole of the Mississippi would end up m

west of New Orleans, causing massive floods and interr

part of the US economy's transport infrastructure.

Needless to say the Army Corps of Engineers has not

Twain's classically retromodern admonition:

One who knows the Mississippi will promptly aver—not aloud b

that ten thousand River Commissions, with the mines of the wor

cannot tame that lawless stream, cannot curb it or confine it, c

"Go here," or "Go there," and make it obey; . . . the Commissio

bully the comets in their courses and undertake to make them

to bully the Mississippi into right and reasonable conduct.25

On the contrary, the Corps has gone to amazing extrem

Mississippi in its course and to help it resist capture by t

Only by letting part of the flow go through the dam ar

finesse this threat, while worrying that severe flooding m

whole structure away.

No matter how fascinating the situation is, I cannot dwell

long, any more than I have the time to follow the tours

War and Peace. I just want to draw attention to the swapping

a portion of McPhee's narrative:

The Corps was not in a political or moral position to kill the At

to feed it water. By the principles, of nature, the more the Atcha

the more it would want to take, because it was the steeper stre

was given, the deeper it would make its bed. The difference in

the Atchafalaya and the Mississippi would continue to increase,

conditions for capture. The Corps would have to deal with that. T

have to build something that could give the Atchafalaya a porti

sippi and at the same time prevent it from taking all.26

The expression "by the principles of nature" does not withdra

the conflicts that McPhee stages between the two rivers,

in Tolstoy's account the "release of the tightly coiled spring

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

10 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

up all the will out of Kutuzo

tion between a smaller but d

one is what provides the goal

a vector, what justifies the wor

thus more dangerous actor.

it is to be an agent. In spite o

goals from "physical" actors,

ways pointing out the danger

we should be just as wary of

them, that is, of giving them

causal antecedents. Especially

activated through a structure

a way to "prevent it from ta

exemplification of Serres's ar

with former natural agents ("t

of view of the other bodies")

engineering could mean: on t

mastery; on the side of the

the engineers says, the quest

capturing the whole river is "

states: "So far we have been

leviate" is a good verb that K

Yes, one could say, but journ

just like novelists; you know

add some action to what, in

will, goal, target, or obsession

and nature, they can't help b

soever. Anthropomorphism is

to sell their newspapers. Wer

objective natural forces," th

The concatenation of causes

real material world is made u

because, precisely—and that'

already there in the cause: no

tion, no metamorphosis, no am

this not what rationalism is all about?

Such at least is the conventional view of the ways in which scientific

accounts should be written; a convention that is maintained in classrooms

and boardrooms, even though it can be disproved by the most cursory

reading of any scientific article. Consider the beginning of this paper

from my former colleagues at the Salk Institute:

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AGENCY AT THE TIME OF THE ANTHROPOCENE 11

The ability of the body to adapt to stressfiil stimuli and the role of

tion in human diseases has been intensively investigated. Cortico

factor (CRF), a 41-residue peptide, and its three paralogous pe

(Ucn) 1, 2, and 3, play important and diverse roles in coordinatin

nomic, metabolic, and behavioral responses to stress. CRF fam

their receptors are also implicated in the modulation of additiona

system functions including appetite, addiction, hearing, and

act peripherally within the endocrine, cardiovascular, reproductive,

and immune systems. CRF and related ligands initially act by

Gprotein-coupled receptors ( GPCRs) ?

Once you factor in the acronyms and replace the passive fo

obligation of the genre) with the action of the scientist

"investigate," here you have actants—first CRF and later in

receptor for CRF—that have all the animation of the M

all the complexities of Kutuzov's decision—so much so

receptor has eluded the ingenuity of this team for half

an inanimate object, to be "implicated" in "appetite, ad

ing, and neurogenesis" and to "act peripherally" within

cardiovascular, reproductive, gastrointestinal, and imm

that's quite a lot of "animation."

As I discovered many years ago in this very same labo

what makes scientific accounts so well suited for a semiotic

there is no other way to define the characters of the ag

lize but via the actions through which they have to be s

Contrary to generals like Kutuzov and rivers like the M

competences—that is, what they are—are defined long afte

mances—that is, what they do. The reason is that the du

is able to imagine, no matter how vaguely, a Russian m

Mississippi River by using his or her prior knowledge. But

case for CRF. Since there is no prior knowledge, every

generated from some experiment. The CRF receptor has

of actions" long before being, as they say, "characterize

competences begin to precede and no longer to follow

This is why the official version of "writing objectively" s

out of date, especially at the time when "an objective

as "at Mauna Loa, on Friday, May 3, the concentration

atmosphere was reaching 399.29 ppm" has not only bec

news, not only a story, not only a drama, but also the plot

And a tragedy that is so much more tragic than all th

since it seems now very plausible that human actors ma

on the stage to have any remedial role. . . Through a co

of Western philosophy's most cherished trope, human

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

12 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

resigned themselves to playing

has unexpectedly taken on th

ening meaning of "global war

background and foreground,

and natural history that is ta

But Gaia is not the same chara

have to supplement the resul

tion. What semiotics designat

visible in texts is what I have c

the "x" standing for the first

thropo-," "angelo-," "phusi-,"

counts at first is not the pre

or shape. The point is that th

the Army Corps of Engineers

shape of a river, of an angel, o

is why it makes no sense to a

committing the sin of "anthr

cies" to what "should have no

deal with all sorts of contrad

to explore the shape of thos

are provided with a style or

recognized actors, they have,

concocted in the same pot. Ev

in novels, scientific concepts, t

born out of the same witches

all of the shape-changers reside

Now the ontological proposit

designates as a common tradi

of the world itself and not onl

Even though it is always diff

(at least in the hands of peop

limited to discourse, to lang

property of all agents in as

true of Kutuzov, of the Mississ

agents, acting means having th

the future to the present, they

the gap of existence—or else

existence and meaning are syn

meaning. This is why such mea

translated, morphed into spee

in the world is a matter of disc

discourse is due to the presen

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AGENCY AT THE TIME OF THE ANTHROPOCENE 13

Storytelling is not just a property of human langua

many consequences of being thrown in a world that

articulated and active. It is easy to see why it will be

to tell our common geostory without all of us—nov

gineers, scientists, politicians, activists, and citizens

closer within such a common trading zone. This is w

Richard Powers has been able to draw so much narr

the inner workings of scientific texts: everything i

that make up the frontier of research articles is act

In the real world time flows from the future to the

what excites scientists as well as readers of Powers's

style is another genre altogether, thanks to which t

of the world, wrongly called "the scientific worldvi

some credence.)29

The reason why such a point is always lost is becaus

during which the "scientific worldview" has reversed th

the idea of a "material world" in which the agency

making up the world has been made to vanish. A z

in which the official version of the "natural world" has shrunk all the

agents that the scientific and engineering professions keep multiplying,

comes from such a reversion: nothing happens any more since the agent

is supposed to be "simply caused" by its predecessor. All the action has

been put in the antecedent. The consequent could just as well not be

there at all. As we say in French: "il n'est là que pour faire de la figuration'

(it is only there to make up the numbers). You may still list the succes

sion of items one after the other, but their eventfulness has disappeared.

(Do you remember learning the facts of science at school? If you were

often so bored, that's why!) The great paradox of the "scientific world

view" is to have succeeded in withdrawing historicity from the world. And

with it, of course, the inner narrativity that is part and parcel of being

in the world—or, as Donna Haraway prefers to say, "with the world."30

In what way does such a proposition—a speculative one, I agree—help

in dealing with Gaia? Why does it seem so important to shift our atten

tion away from the domains of nature and society toward the common

source of agency, this "metamorphic zone" where we are able to detect

actants before they become actors; where "metaphors" precede the two

sets of connotations that will be connected; where "metamorphosis" is

taken as a phenomenon that is antecedent to all the shapes that will be

given to agents?

The first reason is that it will allow us to put aside the strange idea

that those who speak of Earth as a "living organism" are leaning toward

some backward type of animism. The criticism has been leveled against

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

14 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

James Lovelock, as if he ha

tion to the real world of "inan

is correct, Lovelock has don

deanimate many of the conn

up the sublunar domain of

he has refused to sum up al

phor of a single cybernetic

machine. It is not that we s

into its stern and solid stuff

philosophers had tried to d

deanimating the agencies tha

as well as geo-morphology,

not eliminate any of the sou

by former humans, those I

toward a common geostory.

Between matter and material

and polemical act of deanim

the other is a risky, highly

inter-capture (Deleuze's term

the narrativity of the accoun

of them. Matter is produced

present via a strange definit

letting time flow from the

tion of the many occasions t

The paradox of the present

obvious to many scientists t

no journalist, no novelist, w

in the Earth system as, for

the telling title Life as a Geol

we are from Galileo's moons!

The second reason why it is so important to detect this "metamorphic

zone" is political. Traditionally, politics needs to endow its citizens with

some capacity of speech, some degree of autonomy, and some degree of

liberty. But it also needs to associate these citizens with their matters of

concern, with their things, their circumfusa and the various domains inside

which they have traced the limits of their existence—their nomos. Politics

needs a common world that has to be progressively composed.34 Such

composition is what is required by the definition of cosmopolitics. But it is

clear that such a process of composition is made impossible if what is to

be composed is divided into two domains, one that is inanimate and has no

agency, and one which is animated and concentrates all the agencies. It's such a

division between the realm of necessity and the realm of liberty—to use

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AGENCY AT THE TIME OF THE ANTHROPOCENE 15

Kant's expression—that has made politics impossible,

early on to its absorption by The Economy. It's also what

utter impotence when confronted with the ecological

agitate ourselves as traditional political agents longing

such a liberty has no connection with a world of matt

to submit to the realm of material necessity—but such

has nothing in it that looks even vaguely like the freed

of olden times. Either the margins of actions have n

the material world, or there is no freedom left in the ma

engaging with it in any politically recognizable fashion

If the various threads of geostory could ally themselves w

of activity and dynamism, we would be free from the

distinction between nature and society, but also from

efforts to "reconcile" those two distinct domains. Ecolo

suffered just as much from attempts to "recombine" the

nature and society as from the older more violent history

two realms—that of necessity and that of freedom—t

the establishment of a contract implies that there are two

deal: nature and humanity. And nothing is changed wh

ties that are forcefully unified are both understood as "pa

Not because this would mark a too cruel "objectificat

but because such a naturalization, the imposition of s

worldview," would not do justice to any of the agents of g

Mississippi River, plate tectonics, microbes, or CRF re

than generals, engineers, novelists, ethicists, or politic

extension of politics to nature, nor of nature to politics,

to move out of the impasse in which modernism has dug

The point of living in the epoch of the Anthropo

agents share the same shape-changing destiny, a destin

followed, documented, told, and represented by using

traits associated with subjectivity or objectivity. Far from

oncile" or "combine" nature and society, the task, th

task, is on the contrary to distribute agency as far and in

a way as possible—until, that is, we have thoroughly l

between those two concepts of object and subject that

any interest any more except in a patrimonial sense. I a

are condemned by the history of philosophy to the sa

Ulysses when, at the end of the Odyssey, he is condem

to move on with a boat paddk on his shoulder until,

said, he encounters people from a nation so ignorant

ters that they will ask him: "what is this grain shovel tha

you"! The funny thing is that we don't have to travel

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

16 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

encounter people who cannot

subject paddle we carry on o

most science; most of literatur

Living with a world that has n

a big difference for the Eart

stories, when they assemble

is, around things understood

also divide them, the speech

alternate wildly—as was the c

the exact transcription of th

from its referent. Their statem

ways that will no longer be

of political discourse. Convers

decisions entangled with form

on a totally different tenor

new forms that sovereignty h

arena as what stops the discu

"geo" in geostory does not st

return of object and subject

zone"—they had both believ

tion, the other by overanima

a chance to articulate their sp

the articulation of Gaia. The

take on a new lease on life, if

Sciences Po, Paris

NOTES

Lecture prepared for the Holberg Prize Symposium 2013: "From Economics to Ecolo

Bergen, June 4, 2013, under the title "Which Language Shall We Speak with Gai

thank Mary Jacobus for having organized this symposium and Michael Flower for

recting the English.

This work has benefited from the ERC grant "An Inquiry Into Modes of Existence,"

N°269567.

1 Johan Rockström et al, "A Safe Operating Space for Humanity," Nature 461, no. 24

(September 24, 2009) and a vigourous critique in "The Planetary Boundaries Hypothesis :

A Review of the Evidence," http://thebreakthrough.org/archive/planetary_bounda

ries_a_mislead.

2 Bronislaw Szerszynski, Nature, Technology and the Sacred (London: Wiley-Blackwell, 2005) ;

Michael S. Northcott, A Political Theology of Climate Change (Grand Rapids, MI : Wm. B.

Eerdmans, 2013).

3 Michel Serres, The Natural Contract, trans. Elizabeth Macarthur and William Paulson

(Ann Arbor: Univ. of Michigan Press, 1995), 86.

4 James Lovelock, Homage to Gaia: The Life of an Independent Süentist (Oxford: Oxford

Univ. Press, 2000).

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

AGENCY AT THE TIME OF THE ANTHROPOCENE 17

5 Charles D. Keeling, "Rewards and Penalties of Monitoring the Earth,"

of Energy and Environment 23 (1998): 25-82.

6 Dipesh Chakrabarty, 'The Climate of History: Four Theses," Critical I

(2009): 197-222.

7 Bertold Brecht, Life of Galileo (Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin, 1980).

8 Fred Pearce, With Speed and Violence: Why Scientists Fear Tipping Points i

(Boston: Beacon Press, 2007).

9 Mike Hulme, Why We Disagree About Climate Change: Understanding Cont

and Opportunity (Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press, 2009).

10 Alexandre Koyré, From the Closed-World to the Infinite Universe (Baltimore

Univ. Press, 1957).

11 Isabelle Stengers, Cosmopolitics I, trans. Robert Bononno (Minne

Minnesota Press, 2010).

12 Serres, The Natural Contract, 86.

13 Eduardo Kohn, How Forests Think: Toward an Anthropology beyond the

and Los Angeles: Univ. of California Press, 2013).

14 Bruno Latour, An Inquiry into Modes of Existence: An Anthropology of the

Catherine Porter (Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ. Press, 2013).

15 James Lovelock, The Revenge of Gaia: Earth's Climate Crisis and the Fate of

York: Basic Books, 2006).

16 Stengers, Au temps des catastrophes: Résister à la barbarie qui vient (Paris: L

2009).

17 Latour, Facing Gaia: Six Lectures on the Political Theology of Nature. Being t

tures on Natural Religion, http://www.Bruno-Latour.Fr/Sites/Default/F

Gifford-Six-Lectures_l.pdf), 2013.

18 Serres, The Natural Contract, 108-9.

19 Simon Schaffer, "Newton on the Beach: The Information Order of Principia Math

ematical History of Sdence 47, no. 157 (2009): 243-76.

20 David Abram, The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-Than-Human

World (New York: Vintage Books, 1997).

21 Leo Tolstoy, War and Peace, trans. Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky (London:

Vintage Books, 2008), xx.

22 Latour, We Have Never Been Modem, trans. Catherine Porter (Cambridge, MA: Harvard

Univ. Press, 1993).

23 Clive Hamilton, Earthmasters: The Dawn of the Age of Climate Engineering (New Haven,

CT: Yale Univ. Press, 2013).

24 John McPhee, The Control of Nature (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 1980).

25 Mark Twain, Life on the Mississippi (Mineola, NY: Dover Publications, 2000), 131.

26 McPhee, The Control of Nature, 10.

27 Christy Rani Grace et al., "Structure of the N-terminal domain of a type B1 G protein

coupled receptor in complex with a peptide ligand," PN A S 104, no. 12 (2007): 4858-63.

28 Richard Powers, The Gold Bug Variations (New York: William Morrow, 1991); The Echo

Maker (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 2006).

29 Françoise Bastide, Una Notte con Satumo : Scritti semiotid sul discorso sdentifico, trans.

Roberto Pellerey (Rome: Meltemi, 2001).

30 Donna J. Haraway, When Spedes Meet (Minneapolis: Univ. of Minnesota Press, 2008).

31 Stephen H. Schneider et al., Sdentists Debate Gaia: The Next Century (Cambridge, MA:

MIT Press, 2008).

32 Adrian Parr, TheDeleuzeDictionary, rev. ed. (Edinburgh: Edinburgh Univ. Press, 2010).

33 Peter Westbroek, Life as a Geological Force: Dynamics of the Earth (New York: Norton,

1991).

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

18 NEW LITERARY HISTORY

34 Latour and Peter Weibel, eds., Ma

bridge, MA: MIT Press, 2005).

35 Bernard Yack, The Longing for T

from Rousseau to Marx and Nietzsch

1992).

36 Philippe Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture, trans. Janet Lloyd. (Chicago: Univ. of

Chicago Press, 2013).

This content downloaded from

142.157.193.220 on Thu, 22 Dec 2022 20:59:08 UTC

All use subject to https://about.jstor.org/terms

You might also like

- Essentials of Abnormal Psychology 8th Edition Durand Test Bank DownloadDocument38 pagesEssentials of Abnormal Psychology 8th Edition Durand Test Bank DownloadcarrielivingstonocifrtkgnyNo ratings yet

- An Alternative View of The Distant PastDocument361 pagesAn Alternative View of The Distant PastJacobs Pillar75% (4)

- Crutzen and Stormer - The AnthropoceneDocument12 pagesCrutzen and Stormer - The AnthropoceneJulianaNo ratings yet

- The Origins and Evolution of Geopolitics KristofDocument38 pagesThe Origins and Evolution of Geopolitics KristofМаурисио Торрес РамиресNo ratings yet

- Stress, Memory, and The Hippocampus: Can't Live With It, Can't Live Without ItDocument22 pagesStress, Memory, and The Hippocampus: Can't Live With It, Can't Live Without ItsoylahijadeunvampiroNo ratings yet

- Latour Agencyatthe Timeofthe AnthropoceneDocument19 pagesLatour Agencyatthe Timeofthe AnthropoceneisagvidoNo ratings yet

- David Christian, "World History in Context"Document22 pagesDavid Christian, "World History in Context"AndoingNo ratings yet

- Journal of World History, VolDocument18 pagesJournal of World History, VolJay ManalNo ratings yet

- 2012 Cataclysms or Planet XDocument5 pages2012 Cataclysms or Planet XChristine NarvasaNo ratings yet

- Huiracocha Magia Del SilencioDocument26 pagesHuiracocha Magia Del SilenciojsigfridoNo ratings yet

- 2019 Eir Special Report Co2 Redux Is MurderDocument64 pages2019 Eir Special Report Co2 Redux Is MurderMcCrenNo ratings yet

- S06G01 Introduction PDFDocument2 pagesS06G01 Introduction PDFmedialabsciencespoNo ratings yet

- The Oedipal Logic of Ecological Awarenes PDFDocument15 pagesThe Oedipal Logic of Ecological Awarenes PDFDarinko ChimalNo ratings yet

- Sir Martin Rees - Our Cosmic HabitatDocument12 pagesSir Martin Rees - Our Cosmic HabitattheherbsmithNo ratings yet

- Is The Prospect of A Naturally Caused Human Extinction Event FeasibleDocument17 pagesIs The Prospect of A Naturally Caused Human Extinction Event FeasibleNickNo ratings yet

- The Anthropocene, Megalomania, and The Body EcologicDocument14 pagesThe Anthropocene, Megalomania, and The Body EcologicOrlando OrtizNo ratings yet

- Exoplanets: Hidden Worlds and the Quest for Extraterrestrial LifeFrom EverandExoplanets: Hidden Worlds and the Quest for Extraterrestrial LifeNo ratings yet

- The Sediments of Time: My Lifelong Search for the PastFrom EverandThe Sediments of Time: My Lifelong Search for the PastRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (16)

- Summary of A City on Mars by Kelly Weinersmith: Can we settle space, should we settle space, and have we really thought this through?From EverandSummary of A City on Mars by Kelly Weinersmith: Can we settle space, should we settle space, and have we really thought this through?No ratings yet

- Boes & Marshall 2014 PDFDocument13 pagesBoes & Marshall 2014 PDFRene MaurinNo ratings yet

- DASTON YANG Time and Time Again-Deep Time Chicago PRINTDocument24 pagesDASTON YANG Time and Time Again-Deep Time Chicago PRINTSofia LopesNo ratings yet

- Deep Time at The Dawn of The AnthropoceneDocument31 pagesDeep Time at The Dawn of The Anthropocenecri-tiinaNo ratings yet

- The Last Three MinutesDocument97 pagesThe Last Three MinuteswrzosaNo ratings yet

- Jordheim - Natural Histories For The Anthropocene Koselleck S Theories and The Possibility ofDocument35 pagesJordheim - Natural Histories For The Anthropocene Koselleck S Theories and The Possibility ofAlessonRotaNo ratings yet

- Deep Future: The Next 100,000 Years of Life on EarthFrom EverandDeep Future: The Next 100,000 Years of Life on EarthRating: 2.5 out of 5 stars2.5/5 (3)

- Anthropocene and Humanities. DemecilloDocument11 pagesAnthropocene and Humanities. DemecilloMuhaymin PirinoNo ratings yet

- 1.1Document12 pages1.1annie135200No ratings yet

- Boulding, The Economics of Spaceship EarthDocument7 pagesBoulding, The Economics of Spaceship Earthangelo_scribdNo ratings yet

- On The Largest Scale: Big History: The Struggle For Civil Rights (Teachers College Present (New Press)Document6 pagesOn The Largest Scale: Big History: The Struggle For Civil Rights (Teachers College Present (New Press)Elaine RobinsonNo ratings yet

- History and The Scientific WorldviewDocument14 pagesHistory and The Scientific WorldviewduziNo ratings yet

- The AnthropeceneDocument27 pagesThe AnthropeceneOrkhan GafarliNo ratings yet

- This Fleeting World: A Very Small Book of Big HistoryFrom EverandThis Fleeting World: A Very Small Book of Big HistoryRating: 3.5 out of 5 stars3.5/5 (6)

- Cosmic Freedom: David MolineauxDocument2 pagesCosmic Freedom: David Molineauxsalomon46No ratings yet

- Writing PracticeDocument11 pagesWriting Practiceflyond670No ratings yet

- 168 INTRO CATALOG Semi Final PDF - 0Document8 pages168 INTRO CATALOG Semi Final PDF - 0zeebzNo ratings yet

- Nigel Clark - "Rock, Life, Fire Speculative Geophysics and The Anthropocene"Document18 pagesNigel Clark - "Rock, Life, Fire Speculative Geophysics and The Anthropocene"XUNo ratings yet

- Dragon Dreaming - Fact Sheet 2Document26 pagesDragon Dreaming - Fact Sheet 2ningstriNo ratings yet

- Earth's Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It MattersFrom EverandEarth's Deep History: How It Was Discovered and Why It MattersRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (14)

- 309praetDocument16 pages309praetAntoniioninoNo ratings yet

- The Paradox : Our Future is Obscure. Their Past is a MythFrom EverandThe Paradox : Our Future is Obscure. Their Past is a MythRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (4)

- Matter in The Making - Langston Day With George de La WarrDocument92 pagesMatter in The Making - Langston Day With George de La Warrrik100% (3)

- Why Geology Matters: Decoding the Past, Anticipating the FutureFrom EverandWhy Geology Matters: Decoding the Past, Anticipating the FutureRating: 4 out of 5 stars4/5 (6)

- The Great Filter and The Fermi ParadoxDocument6 pagesThe Great Filter and The Fermi ParadoxSantos TreviñoNo ratings yet

- STS 10 N-Module 4 Final AssesmentDocument3 pagesSTS 10 N-Module 4 Final AssesmentFRANCIS GREGORY KUNo ratings yet

- STS 10 N-Module 4 Final Assesment - KuDocument3 pagesSTS 10 N-Module 4 Final Assesment - KuFRANCIS GREGORY KUNo ratings yet

- Astronomy HistoryDocument112 pagesAstronomy HistoryyellowenglishNo ratings yet

- Extinction: Evolution: What Fossils Reveal About The History of Life by Niles Eldredge, Firefly Books 2014Document7 pagesExtinction: Evolution: What Fossils Reveal About The History of Life by Niles Eldredge, Firefly Books 2014Christian MoscosoNo ratings yet

- Nicholas Georgescu-Roegen (1977) A Bioeconomic ViewpointDocument16 pagesNicholas Georgescu-Roegen (1977) A Bioeconomic ViewpointanahialejandrareNo ratings yet

- Antony Cooke Auth. Astronomy and The Climate CrisisDocument294 pagesAntony Cooke Auth. Astronomy and The Climate CrisiscbfodrtfNo ratings yet

- The Worldwide Flood: Uncovering and Correcting the Most Profound Error in the History of ScienceFrom EverandThe Worldwide Flood: Uncovering and Correcting the Most Profound Error in the History of ScienceNo ratings yet

- Marxism and The AnthropoceneDocument22 pagesMarxism and The AnthropoceneClaudio LartigueNo ratings yet

- Documentry On Space TimeDocument2 pagesDocumentry On Space Timetalese.egetadNo ratings yet

- A Time Like No OtherDocument8 pagesA Time Like No OtherCommando719No ratings yet

- Mother Earth: NeedsDocument3 pagesMother Earth: NeedsRaphaël BrouardNo ratings yet

- Douglas 2005Document14 pagesDouglas 2005juan carlos baldizon chavezNo ratings yet

- HyphotalamusDocument21 pagesHyphotalamusAira CostalesNo ratings yet

- Prostaglandins in Pregnancy: Scott W. Walsh, PHDDocument21 pagesProstaglandins in Pregnancy: Scott W. Walsh, PHDIrene AtimNo ratings yet

- Psoriasis + StressDocument8 pagesPsoriasis + StressNiatazya Mumtaz SagitaNo ratings yet

- Physiology of Parturition PDFDocument16 pagesPhysiology of Parturition PDFYoser ThamtonoNo ratings yet

- Hormones of The PlacentaDocument67 pagesHormones of The PlacentagibreilNo ratings yet

- Noaa 56776 DS1Document11 pagesNoaa 56776 DS1saepulakbarNo ratings yet

- HPA Axis in MDDDocument6 pagesHPA Axis in MDDMarie SalomonováNo ratings yet

- Physiology of LaborDocument45 pagesPhysiology of Laborwende kassahunNo ratings yet

- Integrative Therapies For Depression: James M. Greenblatt, Kelly BroganDocument537 pagesIntegrative Therapies For Depression: James M. Greenblatt, Kelly BroganLuk Van Den BoschNo ratings yet

- 5 Keys To Healing YourselfDocument37 pages5 Keys To Healing Yourselfiwantitnowxxx100% (1)

- Topic 1 Endocrine SystemDocument140 pagesTopic 1 Endocrine SystemmasdfgNo ratings yet

- An Introduction To Neuroendocrinology (PDFDrive) (1) - Compressed-83-87Document5 pagesAn Introduction To Neuroendocrinology (PDFDrive) (1) - Compressed-83-87lirNo ratings yet

- DTSCH Arztebl Int-118 0680bDocument3 pagesDTSCH Arztebl Int-118 0680bkeisy MarquezNo ratings yet

- Poverty and BrainDocument24 pagesPoverty and BrainManuel Guerrero GómezNo ratings yet

- Bourke Harrell Neigh 2012 Stress GlucocorticoidsDocument20 pagesBourke Harrell Neigh 2012 Stress GlucocorticoidsConstanceNo ratings yet

- Bringing Basic Research On Early Experience and Stress Neurobiology To Bear On Preventive Interventions For Neglected and Maltreated ChildrenDocument27 pagesBringing Basic Research On Early Experience and Stress Neurobiology To Bear On Preventive Interventions For Neglected and Maltreated ChildrenswhitmansalkinNo ratings yet

- Stress, Eating and The Reward SystemDocument10 pagesStress, Eating and The Reward SystemStefania DuNo ratings yet

- Functional Anatomy of The Adrenal GlandDocument9 pagesFunctional Anatomy of The Adrenal GlandPaula SchaeferNo ratings yet

- Post Traumatic Stress Disorder The Neurobiological Impact of Psychological TraumaDocument17 pagesPost Traumatic Stress Disorder The Neurobiological Impact of Psychological TraumaMariana VilcaNo ratings yet

- Traumatic Stress - Effects On The Brain PDFDocument17 pagesTraumatic Stress - Effects On The Brain PDFDaniel Londoño GuzmánNo ratings yet

- HIGH HISTAMINE - LOW HEALTH - Brainstorm HealthDocument1 pageHIGH HISTAMINE - LOW HEALTH - Brainstorm HealthRodrigo Ferreira100% (1)

- TLSM Student Provider Manual V 2.2.23-CompressedDocument403 pagesTLSM Student Provider Manual V 2.2.23-Compressedcinder.roseNo ratings yet

- Schwabe2010b NLMDocument7 pagesSchwabe2010b NLMMihaela TomaNo ratings yet

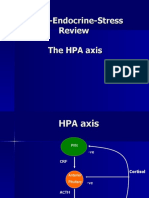

- Brain-Endocrine-Stress Review The HPA AxisDocument14 pagesBrain-Endocrine-Stress Review The HPA AxisChoiruddinNo ratings yet

- Bio NeuroendocrinDocument32 pagesBio NeuroendocrinAlexander Diaz ZuletaNo ratings yet

- VisibleBody Endocrine SystemDocument15 pagesVisibleBody Endocrine Systemcascavelette0% (1)

- DR Anu Arasu How Trauma Affects Your HormonesDocument14 pagesDR Anu Arasu How Trauma Affects Your HormonesShalu SaharanNo ratings yet