Warranty MGMT Essentials 1sted 2024

Warranty MGMT Essentials 1sted 2024

Uploaded by

dmkithureCopyright:

Available Formats

Warranty MGMT Essentials 1sted 2024

Warranty MGMT Essentials 1sted 2024

Uploaded by

dmkithureOriginal Description:

Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Warranty MGMT Essentials 1sted 2024

Warranty MGMT Essentials 1sted 2024

Uploaded by

dmkithureCopyright:

Available Formats

Warranty Management Essentials

1st Edition - 2024

1 Warranty Management Essentials

Table of Contents

1. Introduction ........................................................................................................................................................................................ 4

1.1. Objective of This Paper .................................................................................................................................................................... 4

1.2. Structure and Organization ............................................................................................................................................................ 4

1.3. Revision and Enhancement ............................................................................................................................................................ 5

2. Warranty Concepts .......................................................................................................................................................................... 6

2.1. Warranty ................................................................................................................................................................................................ 6

2.1.1 Terminology ................................................................................................................................................................................ 6

2.1.2 Warranty In The Aircraft’s Lifecycle ................................................................................................................................... 7

2.2. Guarantee ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 11

2.3. Goodwill ............................................................................................................................................................................................... 12

3. Warranty Management – Organization Models Within an Airline ................................................................................... 13

3.1. In-House vs. Outsourced............................................................................................................................................................... 13

3.1.1 In-House Warranty Management ...................................................................................................................................... 13

3.1.2 Outsourced Warranty Management ................................................................................................................................. 14

3.2. Warranty Management – An Interface ...................................................................................................................................... 15

3.2.1 Contracting ............................................................................................................................................................................... 16

3.2.2 Engineering & Maintenance ................................................................................................................................................. 16

3.2.3 Material Department .............................................................................................................................................................. 16

3.2.4 Warranty-Related Groups and Events ............................................................................................................................. 16

3.3. Industry Standards .......................................................................................................................................................................... 17

4. Claims .................................................................................................................................................................................................. 18

4.1. Contractual Basis ............................................................................................................................................................................. 18

4.2. Claimable Items ................................................................................................................................................................................ 18

4.2.1 Parts/Components ................................................................................................................................................................. 18

4.2.2 Service Bulletins ...................................................................................................................................................................... 19

4.2.3 No Fault Found ......................................................................................................................................................................... 19

4.2.4 Access, Inspection, Removal, Installation ...................................................................................................................... 19

4.3. Accounting Principles .................................................................................................................................................................... 19

4.4. New Aircraft Delivery and Commitment Letters ................................................................................................................... 20

5. Mitigations ......................................................................................................................................................................................... 22

6. How To Measure Success ............................................................................................................................................................ 24

6.1. Defining Key Performance Indicators ....................................................................................................................................... 24

6.2. Setting Objectives And Targets .................................................................................................................................................. 24

7. How To Use The MIS for Warranty Management .................................................................................................................. 26

7.1. Definition Stage ................................................................................................................................................................................ 26

7.1.1 Aircraft Level............................................................................................................................................................................. 26

7.1.2 Vendor Level ............................................................................................................................................................................. 26

7.1.3 Part Number Level .................................................................................................................................................................. 26

2 Warranty Management Essentials

7.2. Tracking Stage .................................................................................................................................................................................. 27

7.3. Handling Stage .................................................................................................................................................................................. 27

7.4. Warranty Reporting ......................................................................................................................................................................... 28

8. Roles And Responsibilities ........................................................................................................................................................... 29

8.1. Warranty Process ............................................................................................................................................................................ 29

8.2. Warranty Responsibility ................................................................................................................................................................. 30

9. Acronyms ........................................................................................................................................................................................... 31

10. Contributors ................................................................................................................................................................................... 33

3 Warranty Management Essentials

1. Introduction

The IATA Maintenance Cost Technical Group (MCTG) is an industry group dedicated to supporting the Technical

Operations (Maintenance and Engineering). The aim of MCTG is to work on the reduction of maintenance costs for

the aviation industry as well as to create transparency and insight into these costs.

Warranties are present in most of the categories of aircraft maintenance. The way airlines take advantage of these

contractual rights, which they have paid for, can be very different. There is no standard for handling potential

warranty claims and, for sure, there is no standard for warranty agreements given that warranties may vary from

OEM to OEM, from maintenance supplier to maintenance supplier and from airline to airline.

The MCTG has identified a lack of publications on warranty management and has decided to write this paper to

explain the warranty-related terms and describe the ways to approach warranty elements captured by these terms.

This paper is intended for airlines that do not have any experience in dealing with warranties as well as airlines,

which, although familiar with warranty management, would like to get another view on this topic.

1.1. Objective of This Paper

The objective of this paper is to present the warranty management essentials. It focuses on the following points:

• Explain the process to airlines which are not familiar with warranty management

• Present additional information to airlines having their own warranty management

• Provide a common understanding on warranties in aircraft maintenance

• List the advantages and disadvantages of in-house warranty management

• Show the interfaces a warranty management system might have

• Explain the different contractual bases which could lead to a warranty claim

• Identify claimable items related to warranty in aircraft maintenance

1.2. Structure and Organization

First things first

The paper starts with important definitions and clarifies the differences between warranty, guarantee and goodwill.

It also presents the various possible setups of warranty management as well as the usual interfaces a warranty

department engages in.

Getting to the heart of the matter

Warranty claims are the core of every warranty management. It is important to know which items are claimable,

how to handle warranty claims and how to account for them.

If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it

This famous statement is also applicable to warranty management. This paper shows various ways to manage,

monitor and report warranty claims in the maintenance information systems.

4 Warranty Management Essentials

1.3. Revision and Enhancement

It is MCTG’s first attempt to address the issue of warranty management. This document combines the knowledge

and experiences of its contributors.

In the future, we plan to update this document with all the best practices we will gather. We encourage you to

contact us at mctg@iata.org if you would like to contribute and share your experience too.

5 Warranty Management Essentials

2. Warranty Concepts

In order to have a common understanding, this section reviews the commonly encountered warranty process

concepts and terminology.

2.1. Warranty

2.1.1 Terminology

In this section, we define the term “warranty” in general and explain what it means in the context of aviation and

airline operation. To approach the meaning of warranty, a positive or negative differentiation should be made.

Positive differentiation: What is under warranty?

Warranty is a contractual promise given by the supplier of goods (e.g. an aircraft part) or services (e.g. line

maintenance) that the quality of the goods or services supplied will meet a certain standard of quality, for example

that they will be free from defects in workmanship. The standard of quality will be promised for a certain period of

time, or number of hours/cycles, and the contract will stipulate the Customer’s remedies if the goods or services

do not meet that standard for that time period/number of cycles. The remedies available to the Customer are

usually that the goods/services that have not met the standard will be repaired or replaced, or a refund will be

given.

There are three types of warranty claims available:

• Material and workmanship claims

• Design claims

In addition, warranty claims may be allowable against SBs and /or SLs as well as against Service Life Policies

whenever they affect the contractual promised attributes of the goods or services.

There can be a “First Look” clause, which is coverage over and above the standard warranty period. This clause

describes parts installed at time of delivery, but not inspected during the initial warranty period. These are

considered to be under warranty until the first inspection as per the MPD considering that there may be time limit

linked to the aircraft delivery date (i.e. landing gear, and other main structural areas).

Negative differentiation: What is not under warranty?

Normal “wear and tear” is not covered by warranty of product or component. Omissions or acts by a customer to

not properly service or maintain a component can also invalidate a warranty. Any consequential or incidental

damages are also excluded.

In the process of reclaiming labor hours associated with a warranty claim task, it is important to remember that only

direct labor is claimable. Back-office labor hours and any hours spent troubleshooting or establishing the root

cause of a problem are not claimable. OEMs will also not compensate for ”lost time”. Examples of “lost time”

include:

• Time to schedule the work

• Time to adjust to the workplace

• Time to find and deliver tools/parts

• Time to access the required area/component

6 Warranty Management Essentials

• Time for sealant to cure

• Time to clean up the workplace

• Time to complete paperwork at the end of the task and make claims

Additionally, the consequential costs and loss of revenues are not covered by the warranty provisions.

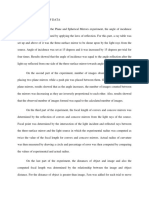

Figure 1. Mapping of the stakeholders and instruments involved in warranty management

Airlines can refer to the aircraft manufacturers’ customer portals for information on warranty management, e.g.

AirbusWorld, MyBoeingFleet, FlyEmbraer, ATRactive, IFlyBombardier, De Havilland Portal, etc.

2.1.2 Warranty In The Aircraft’s Lifecycle

To better understand aircraft warranty, it is necessary to go into details regarding the contract system of OAMs

(Original Aircraft Manufacturers) and component OEMs (Original Equipment Manufacturers), their products, BFE

(Buyer Furnished Equipment) and services of different service providers.

7 Warranty Management Essentials

SUBJECT TO WARRANTY

OAM/OEM OTHER VENDORS

AIRFRAME/AIRCRAFT ENGINES BFE SERVICES

Table 1. Warranty-Related Categories

As shown in the table above, not only OEM parts are subject to warranty. Every type of material and service can be

subject to warranty, which depends on the particular agreement. Therefore, an explanation of the

contracts/agreements for each of the four categories is given below.

2.1.2.1 Airframe/Aircraft

.

Figure 2. Aircraft Warranty Lifecycle

During the particular phases of aircraft lifetime, different contracts are important.

Entry-Into-Service

The aircraft purchaser of an airline inspects the aircraft before issuing the payment on the delivery date. Possible

findings of this inspection, which could not be corrected on time before the planned delivery, can be considered in

a “commitment letter”. These items can be claimed within the agreed timeframe and with respect to the conditions

as contracted. In addition, the aircraft purchase agreement gives information about the warranty period and the

service life policy for each aircraft. The service provides remedies for specified covered components of the

aircraft structure that fail during normal service. This policy provides reimbursement for a replacement part using a

calculation based on the age of the covered component at the time the failure is discovered (i.e. pro-rated

mechanism).

8 Warranty Management Essentials

At the entry-into-service of the aircraft, the airline gets access to the contracts/agreements listed below:

• Aircraft General Terms Agreement (AGTA): The contractual terms that apply to an aircraft purchase

agreement.

• Aircraft Purchase Agreement (PA): Purchase agreement of the aircraft including the warranty and Service

Life Policy (SLP). The timeframe for the SLP is much longer than the Commitment Letter.

• Customer Services General Terms Agreement (CSGTA): Provides terms and conditions that apply, after

aircraft delivery, to the sale or lease of parts, tools, and services.

• Commitment Letter (CML): Agreement that is signed prior to the delivery of the aircraft between the OEM

and/or supplier and the airline. It is independent from the general warranty clause of the purchase

agreement, which means that the agreed conditions can be different from those in the warranty clause.

• Supplier Support Conditions (SSC) / Product Support and Assurance Agreement (PSAA): A negotiated

agreement between aircraft manufacturers like Airbus and Boeing and suppliers of Seller Furnished

Equipment (SFE) that is available to customers and describes the product support, including the warranty.

• Lump sum credit (optional clause): A payment from the OEM to the airline, which prohibits the airline from

claiming warranty-related items lower than a certain agreed amount in general for consumable items.

Rotables are covered under normal OEM warranty repairs.

Warranty period

All of the above-mentioned contracts are still important during the warranty period. The warranty handling in the

aviation industry is different from a warranty handling in other B2C businesses. As a customer, it is normal to claim

only against the one who sold the claimable part. In aviation, all agreements between the OEM and their suppliers

are accessible. This means that, in case a supplier’s part is affected, the operator has to claim against and deal

with the specific supplier directly.

In case of Service Bulletins (SBs), the OEM defines the claimable man-hours and in general the claimable man-hour

rate. This rate is different for every airline as it depends on the region of operation and maintenance. Service

Bulletins are generally not subject to warranty; detailed information can be obtained from the SBs. When Service

Bulletins are not mandatory, the OEM may not provide any commercial support or has to be contacted for an

individual offer.

Regarding warranty issues on OEM parts (parts that are designed and manufactured by the OEM or parts that are

manufactured to their detailed design) and other SFE parts, the airline can only claim:

• Direct materials: non-repairable and non-reusable items such as parts, gaskets, grease, sealant and or

adhesives used when making a correction.

• Direct labor: man-hours spent to access, inspect, remove, repair, test, reassemble and reinstall a

component. Removal and reinstallation may depend on the aircraft type and the agreement.

Troubleshooting or consequential costs are not claimable. For claims regarding OEM parts, the OEM is contacted

while, for claims regarding SFE parts, the suppliers have to be contacted.

In general, there are three different types of OEM/SFE parts an airline can claim for:

• Credit

• FOC material

• FOC repair

It is important to note that, if a part has been replaced by a new part, a new warranty period starts for this part. If it is

replaced by a serviceable part, then the remaining warranty period on the initial part takes precedent

9 Warranty Management Essentials

Post-Warranty Mitigations

As previously mentioned, Service Bulletins are generally not subject to warranty, which means that they may be

claimable out of the warranty period. In addition to that, the Service Life Policy (SLP) coverage starts with the

delivery of the aircraft and ends much later than the warranty period. Moreover, retrofits or other policies could

lead to claimable items, irrespective of the warranty period.

2.1.2.2 Engines

There are some similarities with the aircraft manufacturers. Information about warranties can be found in the

individual purchase agreements, , so that damaged parts of new engines are claimable under the term “new engine

warranty”. During that time and even after that, engines might be affected by SBs as well. In that case, a certain

commitment letter needs to be negotiated, which is the basis for the different SB-claims.

In general, though, the Airline or Operator should have negotiated guarantees (see Section 2.2) with the Engine

Manufacturer to ensure engine performance and have sufficient recovery plans in place for early failures of the

core engine and its LRU’s.

2.1.2.3 Buyer Furnished Equipment (BFE)

Buyer Furnished Equipment (BFE) are parts which have been purchased from a third-party vendor that does not

belong to the OEMs or their supply chain. The purchase agreements have to be negotiated between the parties

individually, and the warranty clause is a result of a separate negotiation and may be totally different from the

OEM’s warranty.

2.1.2.4 Services

Services (e.g. MRO services) have to be contracted, which means that the agreements include warranty clauses

that might lead to claimable items. For example, when an airline outsources a heavy check, it is important to ensure

warranty clauses are written into the contract. Consideration needs to be given into how to keep records and track

of what is warrantable and therefore claimable from either the MRO or the OEM.

Warranty management is based on contractual work, therefore the persons responsible for warranty within an

airline need an unrestricted access to the contract databases.

Pool Contracts

Pool contracts are a very common type of long-term part procurement contracts. Within these contracts, part lists

are defined that are procured by the pool. In case one of the pool parts are declared unserviceable, the airline

sends the unserviceable part to the pool and receives a new or serviceable part in exchange.

Within these contracts, the warranty rights for the airline are normally compensated by the fact that the airline

receives another serviceable part. Depending on the commercial agreement, labor and material costs may be

covered differently by the pool provider and/or the OEM. For example, man-hours – even for the part exchange –

are generally not claimable against the pool provider.

10 Warranty Management Essentials

In the case of a leased aircraft, the pool agreement should be considered in relationship to the aircraft leasing

agreement’s return conditions.

In the case of a brand-new aircraft, if a part fails, the airline needs to be aware that the part can be replaced by a

part that is not new.

In a pool contract, the airline also has the possibility to assign the warranty rights to the pool provider. In return, the

airline gets a lower cost rate. The OEM has to recognize the pool provider as a customer designee.

Software

Software plays an increasingly important role in operating and maintaining aircraft. However, as they are intangible,

software products might not appear in the normal warehousing and material processes and might then be

forgotten in claim/warranty management.

The warranty policies and warranty handling are very poorly defined in today’s Service Level Agreement (SLA)

between OEMs and operators. There has been some work done in this regard by relevant industry groups (e.g.

AEEC software metrics activity, 2015–2018), however it has become evident that software as an aircraft part is

lacking the same defined business practices as a hardware aircraft part (i.e. time between removal for hardware

parts, combining bug fixes with block point updates, other criteria applicable for software world as specified in ITIL

(IT library) practices).

Currently a new workstream at IATA is being launched to address the software reliability metrics, which will include

addressing warranty policies for the software parts.

2.2. Guarantee

Guarantee (as in performance guarantee) is a contractual promise given by the supplier of goods regarding the

operational performance of those goods. A performance guarantee is usually given in respect of the whole aircraft

or engine rather than a smaller part or sub assembly, and the promise given is that the aircraft/engine will perform

to a certain standard. There are conditions attached to the performance guarantee meaning that if the aircraft is

operated outside of those conditions, the guarantee will not be valid. The remedies for the customer if the

aircraft/engine does not perform to the guaranteed standard is monetary, usually in the form of liquidated damages

(i.e. a set amount of money) or a credit against future payments owed to the supplier.

Both “warranties” and “guarantees” are part of a risk sharing agreement between the buyer and the supplier in

order to mitigate the effects of costs of poor quality induced by the sold goods/services.

The warranty is a way of protecting the buyer against early failures of such goods/services, by defining a period –

starting from the EIS – in which the goods/services shall be "free-from-defect”. It is integrated in the Purchase

Agreement (PA) signed between the buyer and the supplier and it is legally binding.

A guarantee can be available. It is a way of protecting the buyer from degraded performance of involved

goods/services from a technical/operational/economical perspective whenever such degradation will occur. If a

guarantee exists, it is integrated in an appendix of the PA, and in general, it could cover reliability (i.e. GMTBUR),

direct maintenance costs (i.e. GDMC), shop processing time (i.e. GSPT) or fuel consumption.

11 Warranty Management Essentials

Example: An OEM provides the avionics suite for an aircraft covering a quite large shipset including the Integrated

Avionic Display (IAD). In the PA with the avionics OEM, we would find a warranty covering an IAD failure within 3

years since its installation on the aircraft, whereas in the PSA we would find a GMTBUR of 10,000 flight hours. This

means that, at the end of the fifteenth year of operation of the aircraft, a given customer could claim against the

avionics OEM in case the reliability data shows that the typical time between two failures of this item is below the

guaranteed value (10,000 FH).

2.3. Goodwill

Goodwill either follows the warranty period or, in case there was no agreed warranty, is replacing it. Goodwill is not

contractually agreed and therefore doesn’t secure the right to claim a financial compensation. Companies

sometimes settle on a goodwill basis:

• For customer loyalty

• For image and reputation improvement

• To avoid excessive paperwork, staff time and administration

12 Warranty Management Essentials

3. Warranty Management – Organization Models Within

an Airline

There are many ways an airline can set up its warranty management. This chapter covers the most common

setups.

First, the airline has to make the strategic choice between managing warranty internally (in-house) or contracting

with an outside supplier (outsourcing). This chapter presents the opportunities and obstacles of each choice, and

the implication on the organization.

Then we describe the interactions of the warranty team with other departments of the airline and external

providers/partners, and the critical factors of success.

3.1. In-House vs. Outsourced

The decision to insource or outsource warranty management is specific to every airline and should be based on

various parameters.

For every “make-or-buy” decision, airlines should perform a thorough cost-benefit analysis in terms of:

• Negotiation and leverage (volume of claims)

• Staff requirements and skills base

• Warranty management tools

• Legal implications

For each of these approaches, various setups of organizational structure are pointed out in this section as well as

“pros and cons” analyses.

3.1.1 In-House Warranty Management

Warranty management requires an interface between several departments within the airline. As it was emphasized

in the previous sections, warranty management mostly consists in contractual work and could be organized within

a contract department.

Other departments are also useful to organize the warranty management:

• Material Management

• Engineering

• Production/Technical operation

• Finance / Financial Planning

• Legal

In any case, a warranty manager has to deal with all these departments, so it requires resources in all departments.

13 Warranty Management Essentials

It is impossible to quote a figure about the necessary number of employees within the warranty department, but

this section should create awareness on the elements that need to be considered:

• IT infrastructure

• IT systems

• Size of fleet

• Homogeneity of fleet

• Age of the fleet (to be carefully reviewed)

• Aircraft types (e.g. new aircraft models need more capacity due to their “childhood diseases”)

• Number of MROs and other service providers

• Number of managed contracts/agreements (e.g. for SBs/CMLs)

• Flow of information within the airline organization

• Number of managed AOCs

PROS CONS

• Less confidentiality concerns • Steep learning curve: limited

• Cheaper expertise/skills in warranty

• Is part of the team and has easier management at the beginning

access to the various internal • Limited leverage: when negotiating

technical subject matter experts for only one airline (especially

(SMEs) smaller airlines)

• Familiar with the processes and • Problems to structure/organize

values of the airline warranty management setup at the

• Better contractual knowledge beginning.

• Better control

• Can reduce turnaround time

Table 2. Pros and Cons of In-house Warranty Management

3.1.2 Outsourced Warranty Management

There are two ways a subcontracted party can act on behalf of an airline.

Appearance as a third-party / different company

A third-party i.e. an authorized agent filing a warranty claim on behalf of a customer airline must have the right to file

a claim. This is typically called an Assignment of Rights Agreement. This is an express written agreement to assign

warranty rights and to be bound by and comply with all the applicable terms and conditions of the General Terms

Agreement with the customer airline.

Appearance as a specific airline

The other way is to integrate third party employees within the specific organization, which means that

subcontractors act as employees of the airline (E-Mail account, OEM access etc.). In this case, an agreement for

being a subcontractor is necessary, but not for claiming on behalf of the airline.

14 Warranty Management Essentials

PROS CONS

• Proven expertise/skills on warranty • Needs access to the airline’s contract

management database and the MRO software

• system concerns about

• Knows how to set up a claim confidentiality

management organization • Needs to be part of the team, as

• Has more power when claiming for warranty management can be seen as

several airlines an interface between several

departments within the airline

• Could be more expensive than in-

house warranty management. (Either

provision or provision + basis fee)

• May not live up to the values of the

airline

Table 3. Pros and Cons of Outsourced Warranty Management

3.2. Warranty Management – An Interface

Known for the harshness of the B2C competitive environment in which they operate, airlines are also in the midst of

the B2B aftermarket revenues battle. Like consumer goods in the 90s, a paradigm shift occurred where OEMs and

OAMs try to sell more and more aftermarket solutions instead of focusing on the original equipment business. The

OAMs’ renewed interest in avionics products development (and the associated aftermarket opportunities) is a

good example.

As the competition intensifies in the aftermarket, airlines are assessing how to interface with their environment and

how to organize in order to maximize their Warranty “Hit Rate”.

By mapping the stakeholders, one might be under the impression that chances of success are little. Airlines that

usually have bargaining power thanks to their critical size (large fleet and high volume of operated flights), a

diversified portfolio (multiple OAMs, open OEM selection for a given functionality, LR/SR operations, etc.), intensive

in-house resources (claim managers, legal department, large engineering teams, etc.) may seem the only ones

likely to succeed. Thankfully, this is not the case.

Far more than its size, the critical success factor for the airline is the alignment of its internal organization and its

warranty strategy.

• Internal Organization:

‒ What the airline is capable of and how it is internally structured to achieve its goal

• Warranty Strategy:

‒ What the airline aims at in terms of support integration (driven by its maintenance support strategy):

▪ Internal

▪ External

▪ Hybrid

‒ Its willingness to invest in a warranty strategy: expertise/skills of the selected internal/external resources.

15 Warranty Management Essentials

3.2.1 Contracting

The Procurement teams will mainly be in charge of drafting/negotiating applicable warranties/guaranties (from

standard PSSA/SSC or GTA between the airline and the vendor). More favorable conditions might be obtained if

there is a significant volume of business for the vendor (large company, OEM/OAM/MRO switch). However, more

favorable conditions on the paper do not mean that these will materialize in terms of compensations in the future. It

highly depends on the efforts/teams put in place to ensure contractual terms are enforced.

Should the Warranty Expert/Team be in the Contract Department? It would depend on the airline’s expertise, its

strategy, and the effort put in it (single staff vs dedicated team). However, given the intricate contractual terms and

the complexity around the topic, a legal expertise would be one of the most critical skills to develop. Required

engineering insights / field reports perspective should be gained also through industry groups, conferences and

workshops.

3.2.2 Engineering & Maintenance

One of the key factors of success of a warranty claim is to build a “bulletproof case”. Every aspect will be

debated/contested on one/several of the following factors:

• Non-compliance with operational conditions stipulated in the warranty

• MRO-driven issue

• No Fault Found (NFF)

• Environmental issues (air pollution)

• Normal wear and tear (what is normal; what was computed/anticipated by the OEM; Or once into operations,

anything that differ from the average wear and tear)

• Fluency in the operator’s maintenance program that helps justify the intervals and/or packaging tasks are

accomplished, and defects found

If the airline’s engineering team is limited in size (small airline/outsourced engineering), the airline can gain insights

through industry working groups and conferences (see section 3.2.4) or through their MRO service provider upon

nominee letter designation (the MRO will claim for the airline).

Closely linked to Engineering, the Maintenance department has the ability to detect failing components and collect

data to build up the claim.

3.2.3 Material Department

If the airline has a Materials/Logistics department, they should have a good understanding of PSAA/SSC ground

rules to understand what they should expect to be offered when buying IP or spares uplift.

3.2.4 Warranty-Related Groups and Events

There are great benefits in joining warranty-related groups and participating in industry events. No matter how

experienced one is, everyone can learn.

16 Warranty Management Essentials

Here are a few reasons to consider:

• Connect with industry peers and discuss common issues that affect everyone

• Learn new skills and gain valuable professional experience

• Have a voice to advocate for the industry

• Stay abreast of the latest industry news and developments enabling participants to be well-informed and

prepared professionals

• Network and meet potential new business partners

3.3. Industry Standards

ATA e-Business Program provide standards for information exchange to support engineering, maintenance,

materiel management and flight operations.

ATA Spec 2000 Chapter 14 provides a standardized set of data formats and implementation guidelines necessary

for a warranty claimant to electronically submit claims to a warrantor. Subscription may be required.

17 Warranty Management Essentials

4. Claims

Claims are the core activities of the Warranty department. A proactive and proficient warranty management results

in maximizing the benefits from the negotiated contracts.

This chapter gives an overview on the contractual basis that needs to be monitored as well as the claimable items.

In addition, some accounting principles and the commitment letters are addressed here.

4.1. Contractual Basis

The table below shows the typical warranty periods for new parts, spare parts and repaired parts at the time of

writing this paper.

New parts for a new AC Spares Parts Repaired Parts

Typically, 36 to 48 months - 36 months of warranty for - 18 months for A380, 787

Warranty Period

A320, A340, 737 and 747 and A350

- 48 months for A380, - 12 months for the other

A350, 777 and 787 fleets

Beginning of the First Property or first Date of the Reception of the Acknowledgement or

Warranty flight regarding the part (and NOT the Data acceptance date.

contract Certificate Release Date)

Time to claim 90 days in general

Table 4. Typical Warranty Periods

Important: The table above is for illustration purpose. Please check the most recent information for each

OAM/OEM.

4.2. Claimable Items

4.2.1 Parts/Components

There are four types of claimable parts:

• New fitted on aircraft

• New spare part

• Repaired within the warranty period

• Equipment issued from a previous standard exchange

18 Warranty Management Essentials

The minimum information to be sent with a warranty claim is:

• Part number

• Serial number

• TSN and TSO

• Reason for removal and date of removal

• Aircraft registration number

If the claim is denied because of wear and tear, the airline can be asked to send pictures

In case the equipment is scrapped within the warranty period, a Free of Charge equipment could be sent by the

OEM (if the scrap is not the airline’s fault).

4.2.2 Service Bulletins

The man-hours described in the SB can be reimbursed if negotiated as well as the parts associated. The warranty

does not imply that the SB will be totally free of charge. In general, if the SB relates to a reliability issue then it

should be FOC, especially if the Airline / Operator is suffering with that part.

It is usually stated in the SB whether it is warrantable or not. Airlines can challenge it on an individual basis,

especially for mandatory SBs that imply a design defect.

4.2.3 No Fault Found

Every OEM/OAM have their own NFF policies. It is recommended to engage with them and understand their

processes and procedures for NFF.

Examples for OAMs

• For a list of Airbus equipment: in case of No Fault Found (NFF), a Post-Flight Report (PFR) has to be sent in

order to prove the NFF. This list of equipment eligible to the NFF program is available on AIRBUSWORLD

• For Boeing equipment (non-restriction): in case of NFF, the correct data proving the NFF has to be

communicated.

4.2.4 Access, Inspection, Removal, Installation

Man-Hours associated with the access, inspection, removal, and installation of an equipment can be claimed. The

claimable duration depends on the warranty conditions of the commercial agreement.

4.3. Accounting Principles

From IFRS1 perspective, airlines need to consider IFRS 92 for definition, measurement and recognition of warranty

claims.

1

International Financial Reporting Standards – www.ifrs.org

2

www.ifrs.org/issued-standards/list-of-standards/ifrs-9-financial-instruments/

19 Warranty Management Essentials

A financial asset includes a contractual right to receive cash or another asset from another entity, pending

warranty claims submitted to OEMs meet this definition as they represent receivables based on contractual

arrangements. Accordingly, these claims are measured within the framework of IFRS 9 Financial Instruments.

Key References

3.1.1 – An entity shall recognize a financial asset when and only when the entity becomes a party to the

contractual provisions of the instrument; Warranty terms and conditions are clearly defined with contracts with

OEMs.

4.1 – The asset would be measured as fair value through profit and loss unless it is measured at amortized

cost. As warranty claims usually do not have an interest component, they can be measured in transaction value. If

the asset recognition criteria are met, airline operators should be able to recognize all open warranty claims in their

balance sheet (through a credit to profit and loss). The movement in open claims between two periods would

represent profit and loss amount taking in to account claims already accepted via credit note or invoice.

5.5.1 – An entity shall recognize a loss allowance for expected credit losses for contract assets; In terms of

warranty claims, loss allowance = 1- Historical Success Rate (or concession rate).

For example, if the historical success rate is 85%, the initial recognition of open claims valued at $100K in ledger

would be:

Debit Record – Warranty Receivables (Financial Asset) - $100K × 85%

Credit Record – Warranty Credits (Profit and Loss) - $100K × 85%

Loss allowance needs to be reviewed and updated on a regular basis.

Please note that the above section is only a guideline and does not constitute a financial advice. It is recommended

that airlines check with their financial accounting team on the details of accounting treatment as well as the

applicability of the IFRS or GAAP 3 standards.

4.4. New Aircraft Delivery and Commitment Letters

Prior to the aircraft delivery to the customer airline and during the final delivery phase, it is recommended to have a

customer representative on site, a Delivery Manager who can then monitor, inspect and follow up on any customer

airline queries. This is for the purpose of verification of the asset and ensuring its conformity to specification. This

individual can inspect the cabin furnishings/interiors and witness ground checks, engine runs and customer

demonstration flights. They can monitor and report on the progress of all snag rectifications consequent to the

above. This is all part of the contractual acceptance process.

There is a need to ensure that the customer’s questions and correction requests are followed up on and agreed by

both parties.

During this period, snags may be discovered that rectification proves untimely, difficult or even impossible given

the remaining time before delivery. In order not to delay the transfer of title and handover date or final contractual

3

GAAP: Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

20 Warranty Management Essentials

acceptance, the issuance of a commitment letter is an acceptable contractual process. This letter is a legally

binding document agreed and signed by both parties whereby the supplier, OEM or vendor (SFE or BFE) may

rectify an identified snag at a convenient point in the future, and free of charge to the customer if it is part of the

agreement. Any deferred items agreed by the customer can also be included in a commitment letter. It should be

noted that this is a negotiated process between all relevant parties, and not a blank check or open-ended period!

Compensation can be monetary, as well as goods, services or fuel.

21 Warranty Management Essentials

5. Mitigations

To reduce the airline’s costs in the unlikely event of failure in maintenance, material or design, different steps might

be considered. This chapter provides a collection of possible actions that could lead to a reduction of maintenance

costs.

• Airlines should indicate their expected minimum warranty terms on component orders e.g. for serviceable

units, for overhauled units and for new components as applicable. They should be proactive and always

negotiate with their vendors.

• Airlines should include OEM participation in their regular trainings for warranty personnel so that they have

a good understanding of warranty, and a basic aircraft system knowledge beyond their financial role

• Airlines can also opt to outsource warranty function/assign to a third party to hold the management of

claims & warranty settlement on behalf of operator where there is insufficient personnel or inexperienced

staff since warranty is a commodity that expires, claims have to be lodged within a given time line from date

of defect discovery or work accomplishment. However, this comes at a cost.

• Airlines to follow-up on declined and disputed claims where there is justification. Declined claims should

not be always accepted by default. OEMs to specify reason(s) for declining or disallowing a claim

• Airlines to setup/integrate their IT systems across functions that would help to check the warranty status

of components and flag units/aircrafts under warranty or act as triggers for same

• Airlines coming together and sharing on their issues, data and experiences relating to warranty and claim

processing by actively participating in existing forums through which airlines share technical experiences

and issues affecting them

• Airlines engaging and creating awareness with internal stakeholders (contracts, production, shops,

engineering, warehouse and Inflight teams) of what is required to lodge a credible claim e.g. photos, BITE

screen shots. This will ensure the claim adjudication/repair process time is as short as possible and to

avoid NFF in the case of repair since not all conditions can be replicated on a bench test.

For Engine and APU

Warranty may not be applicable in case of an engine or module if (and not only if):

• Not being properly installed or maintained; or

• Being operated contrary to applicable OEM recommendations as contained in its manuals, bulletins, or

other written instructions; or

• Being repaired or altered in such a way as to impair its safety of operation or efficiency; or

• Being subjected to misuse, neglect or accident

Some guarantees are only applicable under given average operating conditions (e.g. annual utilization, flight leg,

take-off derate…). More severe operating conditions may require a mutually agreed adjustment.

If a compensation becomes available to the customer under more than one warranty/guarantee, the customer will

not receive multiple compensations but will receive the most beneficial compensation under a single

warranty/guarantee.

The OEM shall not be liable or in breach of its obligations by causes beyond its reasonable control (e.g. war, severe

weather conditions, earthquakes, acts or omissions of customer or customer’s suppliers…).

22 Warranty Management Essentials

For off-wing maintenance

It is the responsibility of the Designated Overhaul Facility (DOF)/Distributor & Designated Overhaul Facility (DDOF)

to verify on a preliminary basis whether the reason for removal of an engine or module is the result of an event that

was within the control of the OEM and therefore covered under warranty.

For off-wing and on-wing maintenance

It is the responsibility of the operator to maintain adequate operational and maintenance records and make them

available for OEM inspection.

23 Warranty Management Essentials

6. How To Measure Success

“If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” This phrase is truly one of the most important ones related to the

economic understanding of any management. The warranty activities have to be measured too, in order to

measure their success. As an approach, KPIs have been defined within this chapter.

6.1. Defining Key Performance Indicators

Key performance indicators (KPIs) are vital tools used by an organization management to understand how the

business is performing. The proper set of indicators will shine a light on performance and highlight areas that need

attention. Here, it is suggested to establish two general high level KPIs that measure both the efficiency of the

handling of the warranty claims process within the organization, and the effectiveness of obtaining the (accurate)

claimed amount. Then, various specific KPIs are developed to monitor the major process of handling claim

processes.

Several parameters should be reviewed in order to design KPI formulae such as:

• Review the contractual basis and set the company objectives

• Identify the claimable items and agree what to achieve (a successful outcome)

• Set benchmarks and standards for the claims process

• Define the department’s involvement in terms of handing process and functions related

The first formula is established to measure the accuracy of claimable amounts:

Raised Amounts − Actual Obtained

KPI = 1− 100%

Raised Amounts

Also, a series of formulae can be developed based on the type of claims.

The second formula is established to measure the process speed in raising the claims

Standard cycle time to prepare the claim − Actual process time

KPI = 1− 100%

Standard cycle time to prepare the claim

Again, a series of formulae can be developed based on the handling process for each involved department.

6.2. Setting Objectives And Targets

Despite some conceptual problems, some airlines budget and set targets for warranty claims.

24 Warranty Management Essentials

Such targets are usually set based on the following parameters:

• Base level claims based on past history and proportional to fleet size and average aircraft age by fleet,

particularly:

o Number of aircraft and engines under warranty

o Number of aircraft and engines which are a new design, which is often more problematic

• Pipeline claims not yet received but claimed

• Agreed contracts and side letters with clauses relating to “warranty performance in relation to technical

dispatch reliability”

• Contractual “failure to perform” clauses agreed with manufacturer

• New and known cases of consistent part (number) failure

• Targets based on number of staff involved in claims or total numbers of claims made

Care should also be exercised not to overclaim for fear of undue friction and administrative costs with

manufacturers, or the possible shifting and substituting of warranty claims into other categories of maintenance

expenditure.

Warranty claims put pressure on the supplier to solve design issues. Often side deals are the result of open claims,

but these are not seen any KPIs. From experience, it is very important to have top management and key account

support. For new tenders, it is important to settle open claims.

25 Warranty Management Essentials

7. How To Use The MIS for Warranty Management

A warranty management module is designed to provide an airline with an automatic method of identifying and then

claiming warranty on different levels, to manage warranty agreements that are in place covering an aircraft, a

vendor, a repair station, or a part / serial number.

The Maintenance Information System (MIS) provide airlines with complete solutions to deal with warranty

management that work through 3 stages abbreviated as “DTH” process (Definition, Tracking, and Handling).

Definition Tracking Handling

Figure 3. DTH Process

7.1. Definition Stage

In the definition stage, the operator determines warranty criteria based on several levels to match with the many

cases that may occur separately or combined. Warranty conditions and dimensions per level can be defined as

follows: aircraft, vendor, part number.

7.1.1 Aircraft Level

The first step within the MIS is “Aircraft definition” where the operator defines whether the new aircraft is owned or

operated by the airline.

There are many items that have to be defined at this stage, e.g. aircraft registration and serial number, fleet type,

owned by, operated by, etc. In addition, the airline can define the conditions and dimensions on the airframe and

the components installed on the aircraft.

7.1.2 Vendor Level

Any operator using a MIS must upload some basic data related to its suppliers, customers, authorities, etc. This

data facilitates work within the IT system to issue purchase orders for suppliers or work orders for customers.

The operator should map the supplier and/or customer’s data with what exists in its Enterprise Resources Planning

(ERP) system if there is interface between the two systems. This will ensure that both systems retain the same level

of basic data.

During the definition stage of certain suppliers within the MIS, the operator can define warranty criteria related to

these suppliers on specific part numbers that have been supplied, at the same time defining the conditions and

dimensions of warranty.

7.1.3 Part Number Level

When receiving rotable items, the operator can define conditions and dimensions of warranty at a part number or a

serial number level.

26 Warranty Management Essentials

7.2. Tracking Stage

Tracking means that the system raises warranty flags for users according to predefined conditions on specific

levels. After the user defines the warranty conditions and dimensions in line with previous step and during ordinary

course of business, the warranty claims are raised when conditions are met.

Example I: If we define a landing gear with serial number 123 that is installed on an aircraft with registration number

XX-SSS “definition on Aircraft level”, the condition of the warranty agreement is free of charge repair if the landing

gear is removed before 3,000 cycles or 10 years whichever comes first. The number of cycles accumulated by the

landing gear is tracked against the aircraft maintenance work. If it is recorded that this landing gear had been

replaced during check on 2,000 cycles only, the system alerts the user that this serial number is still under

warranty.

Example II: If we define a warranty agreement between operator and vendor “XYZ” that focuses on a specific list of

part numbers with agreed conditions, and one of these part numbers does not meet the condition of warranty, the

system will alert the user that this part number is still under warranty.

7.3. Handling Stage

The handling stage identifies the system behavior when warranty conditions are achieved and is split into two

stages:

• Within the MRO IT system

• Interface between the MRO IT system and the ERP system

Within MRO IT System

At the time of the booking of the component, in an unserviceable state, the component records are checked to see

if any potential warranty claim can be made. This can be based on time since new, time since installation, calendar

time, or a time since overhaul or repair. It can check the number of cycles or hours since new or last overhauled or

last repaired.

The potential claims are identified by comparing the component information held in the system against a set of

criteria which have been defined for that part by the Vendor Management team.

When a claim is identified, the system automatically marks the repair order in the system as a warranty claim and

advises the store person. If the store person does not want to claim warranty, they must enter a reason for not

doing so.

When a warranty is claimed, the warranty order for that component is identified with a watermark as a ”warranty

claim”. The order paperwork will also include the details of the reason for the warranty claim.

When the vendor responds to the order, the controller can update the system. They can add details such as

whether the claim has been successful, partially successful, or denied. The reasons for a partial acceptance or

denial of warranty can also be entered into the records to provide a full history. All of this data can then be used to

provide useful statistics regarding warranty claims.

27 Warranty Management Essentials

Interface Between MRO IT System and ERP System

At this stage, after the warranty claim has been raised, financial transactions are required to complete the cycle

and collect the claim. When the operator implements its system, it should design the interface between MRO IT

system and ERP system (e.g. Oracle, SAP, Microsoft dynamic, etc.) to generate related reports and collect the

raised claim through ERP system.

7.4. Warranty Reporting

By continuously gathering data on the warranty claims and their outcome, the system has the ability to generate a

variety of useful reports which help the airline monitor its performance in successfully claiming warranty. These

reports can then be used to target vendors or repair stations which have a poor record of performance with

regards to warranty claims and drive up the number of successful claims.

28 Warranty Management Essentials

8. Roles And Responsibilities

To obtain the full benefit and financial recovery from a warranty process, operators must articulate administrative

roles and responsibilities associated with warranty management. This includes setting up a framework of internal

systems and procedures to confirm all Engineering, Maintenance and Operating costs that may be covered by

warranty are identified and recovered from respective OEMs.

8.1. Warranty Process

Here are some basic considerations in setting up internal procedures for warranty management.

Systems and processes as detailed below will determine that the warranty management processes are effective

with little or no missed opportunities on warranty claims.

STEP SET UP DESCRIPTION

1 Warranty controls Implement controls to identify and capture

warranty opportunities

2 Assess & submit claims Operating systems to submit claims and record

recoveries

3 Manage claims Manage claim process, disputes, recoveries,

reporting

Table 5. Warranty Process

Ensure processes and work flows are defined to include (not limited to) preparation, submission and management

of claims:

1. Warranty claims for the incorporation of system and component improvements introduced via Service

Literature (e.g. Service Bulletins, Service Letters). This may include claims for material and/or labor.

2. Warranty/concession claims that result from business costs incurred as a consequence of OEM products not

performing to specification or an agreed maintenance guarantee (e.g. time on wing guarantee)

3. Airframe warranty claims resulting from Base Maintenance visits

4. Warranty claims resulting from specific Terms and Conditions of OEM Product Support Agreements (PSAs)

and Aircraft/Engine Purchase Agreements

5. Disputed claims for warranty repairs specific to components that have been rejected by OEMs.

6. Monthly reporting detailing status of all claims, recoveries and disputes.

29 Warranty Management Essentials

8.2. Warranty Responsibility

Many operators retain the warranty inputs within business-as-usual processes across engineering and

maintenance teams. Often there is no clear ownership of the associated administrative functions and responsibility

to ensure that all claimable claims are filed, submitted, accepted or contested.

The responsibility for identifying actual and potential warranty opportunities must be carried across the

engineering and line & heavy maintenance teams. However, by appointing a Warranty Administrator whose role

includes ownership for the warranty processes and point of contact internally for all claims across departments

and externally with OEMs could benefit the warranty claim process. The Warranty Administrator is also made

responsible for maintaining the warranty database of opportunities, assessments, claims, disputes and follow-up

actions.

30 Warranty Management Essentials

9. Acronyms

AEEC Airlines Electronic Engineering Committee

AGTA Aircraft General Terms Agreement

AMC Avionics Maintenance Conference

AOC Air Operator Certificate

APU Auxiliary Power Unit

BFE Buyer Furnished Equipment

BOE Boeing

CML Commitment Letter

DDOF Distributor & Designated Overhaul Facility

DOF Designated Overhaul Facility

DTH Definition, Tracking, and Handling

ERP Enterprise Resources Planning

FOC Free of Charge

GAAP Generally Accepted Accounting Principles

GDMC Guaranteed Direct Maintenance Costs

(G)MTBUR (Guaranteed) Mean Time Between Unscheduled Removals

GSPT Guaranteed Shop Processing Time

GTA General Trade Agreement

IAD Individual Avionic Display

IFRS International Financial Reporting Standard

L/G Landing Gear

LCC Low-Cost Carrier

LR/SR Long range / short range

MEC Middle East Carrier

31 Warranty Management Essentials

MMC Mechanics Maintenance Conference

MPD Maintenance Planning Document

MRO Maintenance, Repair and Overhaul

(G)MTBUR (Guaranteed) Mean Time Between Unscheduled Removals

NFF No Fault Found

OAM Original Aircraft Manufacturer

OEM Original Equipment Manufacturer

PFR Post-Flight Report

P/N Part Number

P/O Purchase Order

PA Purchase Agreement

PSAA Product Support and Assurance Agreement

PSSA Product Support and Services Agreement

S/N Serial Number

SB Service Bulletin

SFE Seller Furnished Equipment

SL Service Letter

SLP Service Life policy

SME Subject Matter Expert

SSC Supplier Support Conditions

TSN Time Since New

TSO Time Since Overhaul

32 Warranty Management Essentials

10. Contributors

Dragos Budeanu, IATA

Geraldine Cros, IATA

Chris Markou, IATA

Lucy England, Fox Williams

Keith Fernandes, Virgin Australia

Michael Hansen, Southwest Airlines

Manuel Sabaschus, Eurowings

33 Warranty Management Essentials

You might also like

- IS0 - IEC 27001 Implementation GuideDocument79 pagesIS0 - IEC 27001 Implementation GuideJABERO861108100% (9)

- Counter-Fraud Framework Saudi Central BankDocument64 pagesCounter-Fraud Framework Saudi Central BankMNA SiddikiNo ratings yet

- ch07 - Inventory and Price ManagementDocument75 pagesch07 - Inventory and Price ManagementFATIN FARZANA NASORUDDIN100% (1)

- P6 Training Content From PMP INN Learning 1683146231Document95 pagesP6 Training Content From PMP INN Learning 1683146231Anjum BasraNo ratings yet

- Sap MM Functionality TechnicalDocument53 pagesSap MM Functionality Technicalmanohar_sh60% (10)

- Last FinalDocument55 pagesLast Finalashikipe16No ratings yet

- The International Attribute Tracking Standard v1.0Document66 pagesThe International Attribute Tracking Standard v1.0Muhammad Umer KamalNo ratings yet

- HAL Outsourcing Manual-Rev 05 2024Document102 pagesHAL Outsourcing Manual-Rev 05 2024Guna100% (1)

- Chapter 1 5 Mancon Last Na Ito Punyeta NamanDocument70 pagesChapter 1 5 Mancon Last Na Ito Punyeta NamanJeremy Grant AmbeNo ratings yet

- BIM ManualDocument143 pagesBIM ManualBassemBahaaNo ratings yet

- FPM SETA Sector Skills Plan 2018-22Document66 pagesFPM SETA Sector Skills Plan 2018-22Cindy De LeeuwNo ratings yet

- MANUAL DEALER EN Ver.2.6Document77 pagesMANUAL DEALER EN Ver.2.6Renato SanchezNo ratings yet

- Lippo Shop 18 Apr 01 BylippoDocument88 pagesLippo Shop 18 Apr 01 BylippoRizkyAufaS100% (1)

- Detailed Business Continuity Plan Sample PDFDocument23 pagesDetailed Business Continuity Plan Sample PDFdexi100% (2)

- QHSE Employer RequirementsDocument70 pagesQHSE Employer Requirementsafas100% (1)

- Mastercard Switch Rules ManualDocument106 pagesMastercard Switch Rules Manualkamal_aheddajNo ratings yet

- Outline Project ManagementDocument166 pagesOutline Project ManagementKimoTeaNo ratings yet

- Ballarat ELS Final Draft 31 July 2021Document182 pagesBallarat ELS Final Draft 31 July 2021Pat NolanNo ratings yet

- MBA Marketing ProjectDocument67 pagesMBA Marketing Projectjac76248No ratings yet

- EC Integration GuideDocument56 pagesEC Integration GuideMrPollitoNo ratings yet

- Principles of Accounting II-1Document127 pagesPrinciples of Accounting II-1michuusabaNo ratings yet

- ARCM - Modeling ConventionsDocument126 pagesARCM - Modeling ConventionsAlberto R. Pérez MartínNo ratings yet

- Valuation Report 1Document64 pagesValuation Report 1azureglobal.digitalNo ratings yet

- Market System Analysis Inspira 2019Document152 pagesMarket System Analysis Inspira 2019sarwat iqbalNo ratings yet

- Zkbiosecurity User Manual v2.4 20181026 For 3.1.5.0 or AboveDocument412 pagesZkbiosecurity User Manual v2.4 20181026 For 3.1.5.0 or AboveJalo MaxNo ratings yet

- Equipment Planning GuidelinesDocument49 pagesEquipment Planning GuidelinesMaraNo ratings yet

- JPK Manual NanoWizard-Series V7(2)Document194 pagesJPK Manual NanoWizard-Series V7(2)Terry ShenNo ratings yet

- Reference Manual Rev 2.0Document62 pagesReference Manual Rev 2.0Rohman AzizNo ratings yet

- 4Document1 page4Abidzar Al-ghifariNo ratings yet

- M01-Preventing and Eliminating MUDADocument51 pagesM01-Preventing and Eliminating MUDAMartha BelayNo ratings yet

- Equities by Money Market, BNGDocument263 pagesEquities by Money Market, BNGsachinmehta1978No ratings yet

- Call Centre Establishment GuidelineDocument44 pagesCall Centre Establishment Guidelinemusab-salah-796967% (3)

- Ba WTB en D49019Document36 pagesBa WTB en D49019Ngô Mạnh CườngNo ratings yet

- World Bank-Cloud Readiness Pilot Assessment Report Final-PUBLICDocument82 pagesWorld Bank-Cloud Readiness Pilot Assessment Report Final-PUBLICrajutamang2021.btNo ratings yet

- Field HR Management Guideline (En) V5-August 2014Document32 pagesField HR Management Guideline (En) V5-August 2014Ashraf Albhla100% (1)

- Garment Study - Final Report - 26.02.2018 PDFDocument106 pagesGarment Study - Final Report - 26.02.2018 PDFAli AhmadNo ratings yet

- VitalPBXReferenceGuideVer2EN PDFDocument233 pagesVitalPBXReferenceGuideVer2EN PDFoffice engitechNo ratings yet

- A Guide To Hedge Accounting 20231219Document172 pagesA Guide To Hedge Accounting 20231219Jarryd MusngiNo ratings yet

- Business Plan MalawiDocument84 pagesBusiness Plan MalawiRichard Chinyama Chikeji NjolombaNo ratings yet

- Rashid Bakari Business Plan Final 1 PDFDocument32 pagesRashid Bakari Business Plan Final 1 PDFrashdexx777No ratings yet

- 4national Grid Code For Power TransmissionDocument266 pages4national Grid Code For Power TransmissionSamuel TesfayNo ratings yet

- City Taxi Management System-S.H. Bodahewa - 23042028Document98 pagesCity Taxi Management System-S.H. Bodahewa - 23042028thenura1979No ratings yet

- Vitalpbx Reference Guide Ver. 2.2.2Document233 pagesVitalpbx Reference Guide Ver. 2.2.2Garry MooreNo ratings yet

- Hydra Billing User Guide PDFDocument457 pagesHydra Billing User Guide PDFomuhnateNo ratings yet

- Operation Manual Sidexis 4.3Document370 pagesOperation Manual Sidexis 4.3مصعب بابكرNo ratings yet

- Bridal Sutra PDFDocument97 pagesBridal Sutra PDFdilanhjNo ratings yet

- 20220910-Strategic ManagementDocument76 pages20220910-Strategic Managementabdelrahman.hashem.20No ratings yet

- Manager Accounts 20200608Document513 pagesManager Accounts 20200608dillibabu r100% (1)

- Endline Evaluation FINALDocument144 pagesEndline Evaluation FINALMkm MkmNo ratings yet

- Contract Management Guide - Ver 1 2010Document101 pagesContract Management Guide - Ver 1 2010Abderrahman QasaymehNo ratings yet

- SD Safami ScopeDocument30 pagesSD Safami Scopekirangandham8No ratings yet

- Establishing CSIRT v1.2Document45 pagesEstablishing CSIRT v1.2ricardo.rodriguezv100% (1)

- Efiling ManualDocument120 pagesEfiling ManualKeep GuessingNo ratings yet

- Tari Water Supply - Technical Specs. KM (Final Clean)Document95 pagesTari Water Supply - Technical Specs. KM (Final Clean)Warren DiwaNo ratings yet

- Manager PDFDocument520 pagesManager PDFImad Yousif100% (1)

- Corporate Management, Corporate Social Responsibility and Customers: An Empirical InvestigationFrom EverandCorporate Management, Corporate Social Responsibility and Customers: An Empirical InvestigationNo ratings yet

- Drafting Purchase Price Adjustment Clauses in M&A: Guarantees, retrospective and future oriented Purchase Price Adjustment ToolsFrom EverandDrafting Purchase Price Adjustment Clauses in M&A: Guarantees, retrospective and future oriented Purchase Price Adjustment ToolsNo ratings yet

- Entering the Brazilian Market: A guide for LEAN ConsultantsFrom EverandEntering the Brazilian Market: A guide for LEAN ConsultantsNo ratings yet

- Crafting ProtectionDocument5 pagesCrafting ProtectionRemus TuckerNo ratings yet

- Online Summer ReportDocument13 pagesOnline Summer ReportDevender DhakaNo ratings yet

- Der Neue Polo 1.0 TSI 85 KW (115 PS) : Engine, ElectricsDocument1 pageDer Neue Polo 1.0 TSI 85 KW (115 PS) : Engine, ElectricsrobbertmdNo ratings yet

- Panel Solar Jinko JKM325-345M-60H - (V) - A3-EnDocument2 pagesPanel Solar Jinko JKM325-345M-60H - (V) - A3-Enronalde90No ratings yet

- Binario Rede NeuralDocument11 pagesBinario Rede NeuralivanlbragaNo ratings yet

- Tgs Bhs InggrisDocument2 pagesTgs Bhs InggrisFitri melaniNo ratings yet

- BBC How Long Will Life LastDocument21 pagesBBC How Long Will Life LastLamantT100% (1)

- Barr StadiaDocument35 pagesBarr StadiaSwerveEFCNo ratings yet

- 82 Software Safety Analysis ProceduresDocument18 pages82 Software Safety Analysis ProceduresMilorad PavlovicNo ratings yet

- E402Document3 pagesE402Calvin Paulo MondejarNo ratings yet

- FeedbackDocument43 pagesFeedbackJanmarc CorpuzNo ratings yet

- Share TemplateDocument20 pagesShare TemplatemalaysiandanNo ratings yet

- III ConditionalDocument2 pagesIII ConditionalАлександр ЧебанNo ratings yet

- Grade 4: First Additional Language Lesson Plan EnglishDocument206 pagesGrade 4: First Additional Language Lesson Plan EnglishNomvelo KhuzwayoNo ratings yet

- Now and Get: Best VTU Student Companion You Can GetDocument7 pagesNow and Get: Best VTU Student Companion You Can GetVaidyanatha PNo ratings yet

- FM Part-4Document190 pagesFM Part-4Shivam PatidarNo ratings yet

- Burger King Vegetable Preparation 123456789Document12 pagesBurger King Vegetable Preparation 123456789ScribdTranslationsNo ratings yet

- Decoding Bug Bounty Programs: Jon RoseDocument72 pagesDecoding Bug Bounty Programs: Jon RoseAdil Raza SiddiquiNo ratings yet

- Anti Money Laundering (AML) Learnings From Banks: Compliance Group-AML July 16, 2010Document23 pagesAnti Money Laundering (AML) Learnings From Banks: Compliance Group-AML July 16, 2010Mahapatra Milon100% (1)

- Presence of Garcinol in Garcinia Binucao FINALDocument22 pagesPresence of Garcinol in Garcinia Binucao FINALattyvan100% (1)

- Civil Hydraulics Lab ReportDocument24 pagesCivil Hydraulics Lab ReportKevin OnyangoNo ratings yet

- Matrix Diagram - : L-ShapedDocument6 pagesMatrix Diagram - : L-ShapedSead ZejnilovicNo ratings yet

- ICSE Class 10 Physics Important QuestionsDocument2 pagesICSE Class 10 Physics Important QuestionsOverRush Amaresh100% (1)

- Framework of Autonetics IN Attendance Muster Survey and SummarizationDocument10 pagesFramework of Autonetics IN Attendance Muster Survey and Summarizationramalingam rNo ratings yet

- 22PAM0062 - INTERMEDIATE ACADEMIC ENGLISH - Part1Document17 pages22PAM0062 - INTERMEDIATE ACADEMIC ENGLISH - Part1Dwi Nurvidi PriliaNo ratings yet

- The Band of The Broken AnvilDocument8 pagesThe Band of The Broken AnvilnazrukNo ratings yet

- Fnaf Wall - Szukaj W GoogleDocument1 pageFnaf Wall - Szukaj W GoogleciemnagabrysiaNo ratings yet

- Manuscript 1 PDFDocument8 pagesManuscript 1 PDFDiyar NezarNo ratings yet

- Design Thinking The Evolution of Human Centred DesignDocument4 pagesDesign Thinking The Evolution of Human Centred DesignsatheeshNo ratings yet