UrbanAffairsReview 2014 Hendriks 553 76

UrbanAffairsReview 2014 Hendriks 553 76

Uploaded by

James UgbesCopyright:

Available Formats

UrbanAffairsReview 2014 Hendriks 553 76

UrbanAffairsReview 2014 Hendriks 553 76

Uploaded by

James UgbesOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

UrbanAffairsReview 2014 Hendriks 553 76

UrbanAffairsReview 2014 Hendriks 553 76

Uploaded by

James UgbesCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/261537374

Understanding Good Urban Governance:

Essentials, Shifts, and Values

Article in Urban Affairs Review · July 2014

DOI: 10.1177/1078087413511782

CITATIONS READS

112 3,322

1 author:

Frank Hendriks

Tilburg University

285 PUBLICATIONS 2,513 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Frank Hendriks on 03 March 2015.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

Urban Affairs Review http://uar.sagepub.com/

Understanding Good Urban Governance: Essentials, Shifts, and

Values

Frank Hendriks

Urban Affairs Review 2014 50: 553 originally published online 4 December 2013

DOI: 10.1177/1078087413511782

The online version of this article can be found at:

http://uar.sagepub.com/content/50/4/553

Published by:

http://www.sagepublications.com

On behalf of:

The Urban Politics Section, American Political Science Association

Additional services and information for Urban Affairs Review can be found at:

Email Alerts: http://uar.sagepub.com/cgi/alerts

Subscriptions: http://uar.sagepub.com/subscriptions

Reprints: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsReprints.nav

Permissions: http://www.sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Citations: http://uar.sagepub.com/content/50/4/553.refs.html

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

>> Version of Record - Jun 23, 2014

OnlineFirst Version of Record - Dec 4, 2013

What is This?

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

511782

research-article2013

UAR50410.1177/1078087413511782Urban Affairs ReviewHendriks

New Direction

Urban Affairs Review

2014, Vol. 50(4) 553–576

Understanding Good © The Author(s) 2013

Reprints and permissions:

Urban Governance: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

DOI: 10.1177/1078087413511782

Essentials, Shifts, and uar.sagepub.com

Values

Frank Hendriks1

Abstract

Building on the relevant international literature, as well as empirical research

on urban cases, this article determines and discusses five core values of

good urban governance: responsiveness, effectiveness, procedural justice,

resilience, and counterbalance. The quest for good governance can take

various forms. This article focuses on urban governance, and identifies four

different shifts, with increased emphasis on the real decision makers or the

ordinary citizens, with increased attention to selective choice or integrative

deliberation as modes of urban governance. Urban governance and good

urban governance are not synonymous. This article advocates critical

reflection, moving beyond the performance bias that tends to accompany

governance reform.

Keywords

urban governance, good governance, democracy, rule of law, responsiveness,

effectiveness, procedural justice, resilience, counterbalance, urban regime,

urban market, urban trust, urban platform.

Good Urban Governance Revisited

This article combines discussions about urban governance with discourse on

good governance, taking the latter back into the urban realm. Contemporary

1Tilburg University, Tilburg, Netherlands

Corresponding Author:

Frank Hendriks, Public Administration, Tilburg School of Politics and Public Administration,

Tilburg University, Warandelaan 2, Tilburg 5037 AB, Netherlands.

Email: F.Hendriks@uvt.nl

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

554 Urban Affairs Review 50(4)

urban cases are, thus, connected to the long-standing debate, in which the

Italian town of Siena plays a pivotal role.

In the Siena town hall, we find the world-famous fourteenth-century paint-

ings by Lorenzetti depicting the precepts and effects of good governance in

the city. The painting Effeti del Buon Governo in Città shows citizens living

peacefully together, engaging in transactions and alliances. Lorenzetti sug-

gests that these good effects follow from “good governance,” illustrated by

his Allegoria del Buon Governo in Città. This painting nicely exemplifies

that good governance is more than “doing good things.” Good governance is

about doing things in a sound institutional setup, characterized by effective

checks and balances and countervailing powers—as we have subsequently

come to call them in the wider framework of the democratic rule of law. As a

medieval artist, Lorenzetti did, of course, not use these terms but worked with

images. His allegory of good governance depicts a diversified institutional

setting that knows no absolute power, but power checked by Lady Justice as

well as a train of free citizens, and led by cardinal virtues such as prudence,

temperance, magnanimity, and fortitude.

If we were to make a Buon Governo in Città for today’s urban areas, what

should we highlight as essential? What qualities and characteristics of urban

governance need to be stressed? In addressing this question—in social sci-

ence language rather than painting—this article will link up with the relevant

literature, which has gone through a much-discussed “shift from government

to governance” (Bevir 2010; Kjaer 2004; Pierre 2000; Rhodes 1996, 2000)

and appears to be witnessing a further shift from governance to “good gover-

nance” (Ahrens, Weingarth, and Caspers 2010; Bovaird and Löffler 2003;

Mulgan 2006; Rothstein and Teorell 2008).

The aim of this article is not to present an exhaustive overview of all the

literature on governance and good governance. The aim is, more modestly, to

determine the essential elements and dimensions of urban governance and to

develop a framework for understanding good urban governance. The relevant

international literature constitutes a means to this end, in addition to empiri-

cal research into the quest for good governance (QGG) in a series of Dutch

cities.1

Although the terminology on governance has its shortcomings (more

about this in the next section), it has two major advantages for present pur-

poses. First of all, the governance concept calls our attention to the fact that

governing in the urban realm involves more than “city hall” as a metaphor for

monocentric government in the city. “Local government” is no more (and no

less) than one constituent part of “urban governance.” Second, and perhaps

more importantly, if we widen the concept of governance to “good gover-

nance,” this will encourage us to reflect more systematically on what quality

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

Hendriks 555

is in the art of administration, opening the door to a rich and diversified

understanding of administrative value(s). The urban realm is a suitable test-

ing ground for doing so (Pierre 2005; Stoker 2000).

Urban Governance: Essential Features

As a theoretical construct, “governance” has all the characteristics of a con-

tainer concept. It contains a lot, and it is hard to tell where it exactly begins

and ends. In Public Administration, not the only discipline that works with

the concept, governance usually refers to the steering of service domains or

problem areas characterized by interdependence among various involved

parties and organizations (Kjaer 2004; Rhodes 2007). The often invoked

image in governance discourse is that of a hampered government system,

characterized by limited steering capacity, far removed of a steering monop-

oly (Hajer and Wagenaar 2003; Pierre 2000; Swyndegouw 2005). Alternative

steering models would be indispensable in the light of profound technologi-

cal, economic, and social transformations (Rhodes 1997). This would drive

the fundamental shift “from government to governance,” whereby the former

is understood as vertical, monocentric, and unilateral steering, and the latter

horizontal, pluricentric, and multilateral (Bevir 2010; Pierre 2000).

In the international literature, the general concept of “governance” has

acquired a great many definitions, some of which do and some of which do

not coincide (Rhodes 2000). All those definitions will not be reproduced

here. The aim is the reduction, not the reproduction, of complexity. Here, the

concept of—urban—governance refers to the more or less institutionalized

working arrangements that shape productive and corrective capacities in

dealing with—urban—steering issues involving multiple governmental and

nongovernmental actors. The following subsections will give some further

explication of the essential elements of this definition.

Working Arrangements, More or Less Institutionalized

Governance literature and practice show that working arrangements may be

of very different kinds. Government does not always play a leading role in

this. Sometimes government barely seems to matter: “governing without

government” as Rhodes (1996) called this in a famous and controversial

phrase (cf. Peters and Pierre 1998). In the urban realm, one might think of the

residents’ associations that govern and manage certain neighborhoods in Los

Angeles seemingly by themselves. Local government in the traditional sense

seems to play a relatively modest role indeed, but even here it has not disap-

peared out of the picture altogether. Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD),

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

556 Urban Affairs Review 50(4)

to mention just one department, can still intervene, even when private secu-

rity does a lot of the day-to-day surveillance.

“Governance without a lot of government” is by no means the only theo-

retical variant. Lowndes and Skelcher (1998), Pierre and Peters (2000),

Kooiman (2003), Bovaird (2005), and others distinguished different “modes

of governance,” which would include “networks,” “markets,” and “hierar-

chies.” These are three basic modalities that occur in various blends in exist-

ing urban governance models. In the Los Angeles blend of urban governance,

the market mechanism and the mode of self-organization are comparatively

more prominent than, for example, in the Dutch mixture of governance

modalities, in which government and top-down planning remain relatively

important (Hendriks and Musso 2004).

In a realistic approach to urban governance, government and hierarchy

may be downplayed, as city hall is indeed not a city’s control center, but they

cannot be defined away altogether (Stoker 2011). The idea that modern gov-

ernance is a web of purely horizontal, nonhierarchical relations is an unreal-

istic one, as is the idea that working arrangements in dealing with public

problems could be purely nonformal, without any official strings attached.

Governance is a compound of both horizontal and vertical, both nonformal

and formal arrangements that have structural significance for public issues,

here in the urban realm (cf. Haus, Heinelt, and Stewart 2005; Peters and

Pierre 1998; Stoker 1998).

To do something in a particular way, for a limited amount of time (ad hoc),

does not yet amount to “governance.” This would require some regularity, a

certain level of institutionalization. The working arrangements of urban gov-

ernance can be understood as institutions in the sense of “rules in use” (E.

Ostrom 2005).

Productive and Corrective Capacity in Multi-actor Settings

The focus is on working arrangements that shape productive and corrective

capacity in dealing with—urban—issues by multiple (non)governmental

parties. This involves, on one hand, the mobilization of organizing and per-

forming abilities, and, on the other, the mobilization of controlling and

counterbalancing abilities.

Contemporary literature on urban governance tends to focus mostly on

productive capacity, on the working arrangements that are instrumental in the

production of public goods and services, in getting things done in the urban

realm. A good example is the urban regime approach by Stone (1989, 2006).

With his seminal study on Atlanta, Stone (1989) cut right across the “com-

munity power debate” between elitists and pluralists. In Stone’s view, both

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

Hendriks 557

these parties were too obsessed with power over (who was having power over

whom), rather than with power to (how are things actually accomplished?).

Flyvbjerg (1998), in his detailed study of Aalborg, Denmark, indeed observed

that the heart of the matter was not so much “Who governs?” but more “How

is the governing being done?” and how is power being executed in this.

Although just as important, the issue of how checks and balances and

countervailing powers are institutionalized has received less attention in

today’s urban governance literature. These issues are usually associated with

national constitutions. Yet discourse on corrective capacity originated in

highly polycentric urban domains. As highlighted in the introduction, the

allegory Buon Governo in Città was all about the checks and balances pro-

vided by institutions and powers around the government of a city like Siena,

comparable with cities like Florence, Genua, Venice, and other city-states

(Finer 1999). One of the most spectacular examples of “multiactor gover-

nance” in a sprawling “urban field”’ manifested itself still earlier: Republican

Rome (not to be confused with the latter-day Empire).2

It is remarkable and a pity that, in the contemporary debate on urban gov-

ernance, the framing of checks and balances is given less consideration than

in the current discourse on corporate governance, in which the “constitu-

tional” relations between CEOs, boards of directors, supervisory boards,

assemblies of shareholders, and other stakeholders have been hotly debated

(Pietrancosta 2009). In urban governance, there are many fragmented

“offices” that can and should be understood in terms of countervailing forces:

local councils, neighborhood councils, mayor and aldermen, urban district

coordinators, higher level co-governments, civil service departments, ombud-

spersons, audit committees, housing corporations, welfare organizations,

community work agencies, municipal advisory councils, chambers of com-

merce, residents’ organizations, neighborhood management companies, indi-

vidual citizens, and so on. Their added value should be assessed not only in

productive or instrumental terms but also in terms of corrective capacity (cf.

V. Ostrom 1982).

Shifts in Urban Governance: Main Directions

One of the clichés of contemporary Public Administration is the so-called, and

presumably relatively recent, “shift from government to governance.” Such a

dichotomous “from A-to-B” scheme is a misrepresentation of reality. As said,

ancient Rome and the city-states of Northern Italy already displayed a lot of

governance. The same could be said of the equally polycentric urban field of

the seventeenth-century Dutch Republic (Israel 1995). So, urban governance

is far from new, although it is real, important, and constantly developing.

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

558 Urban Affairs Review 50(4)

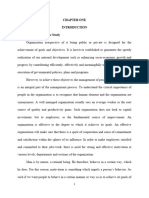

Figure 1. Shifts in urban governance.

Another thing that we should be aware of is that, in today’s urban arena,

there is still a substantial role cut out for government within the context of

urban governance. City hall is not the city’s “cockpit” where all the steering

comes from, but mayors, city councils, and other official actors, some of

them supra-local, continue to play a role that often goes beyond the “shadow

of hierarchy” metaphor coined by Scharpf (1997). The building of an urban

ring road still needs public funding, the development of a new business park

depends on zoning, and the weaker parties in the proverbial urban jungle still

rely on government protection and support.

Rather than thinking in terms of a singular replacement of one thing by

another, we should be thinking in terms of varied shifts in more or less insti-

tutionalized working arrangements, involving both new and old types of

steering, both nonformal and formal rules, and both horizontal and vertical

types of relationships.

Tracking Urban Governance: A Typology

Varied shifts in working arrangements were clearly visible in the Dutch QGG

research, on which the argument here is partly based (see Note 1; Hendriks

and Drosterij 2012). Dutch cases of urban governance, extensively analyzed

in the QGG research, will serve to illustrate the typology of shifts in urban

governance proposed in Figure 1, but this typology has heuristic value for

tracing such shifts in urban fields elsewhere in the Western world.3 Emerging

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

Hendriks 559

modalities of urban governance in places like Berlin, Milan, Ghent, Dublin,

Munich, and Melbourne can and will be linked to the ideal-typical patterns

proposed below.

To make sense of contemporary shifts in urban governance, Figure 1 dis-

tinguishes between four main directions in which such shifts can be traced:

•• There may be increased attention to and emphasis on “real decision

makers”—social and economic elites—in the urban realm (A) or, con-

versely, on “ordinary citizens” in the various neighborhoods and dis-

tricts (B).

•• There may be increased attention to and emphasis on “integrative

deliberation” as a more communicative, comprehensive way of

approaching alternatives and making collective decisions (C), or, con-

versely, on “selective choice” as a more competitive, exclusive mecha-

nism for weeding out the options and getting to public choice (D).

Track A, emphasizing real decision makers, is founded on the idea that, if

you really want to accomplish anything in the urban domain, you need to

accost the business elites and other key figures in society and involve them in

decision-making processes (cf. Hunter 1953; Lauria 1997; Stone 1989).

Track B, stressing ordinary citizens, proceeds from the idea that democratic

government should not only be for citizens but also by citizens and that the

widespread tendency to govern while ignoring citizens themselves ought to

be rectified as much as possible (Box 1998; Hoggart and Clark 2000;

Swyndegouw 2005).

Track C, focusing on more integrative deliberation as a mode of coordina-

tion, is a response to the feeling that a DAD (Decide-Announce-Defend) type

of rule is outmoded and that talking things through is a better response to

complex issues; the round table is an apt metaphor here for a more delibera-

tive, communicative, and comprehensive mode of decision making (Berry,

Portney, and Thompson 1993; Goodin 2008; Uitermark and Duyvendak

2008). Track D, underlining more selective choice, could be captured in the

metaphor of free nature, comprising the evolutionary logic of natural selec-

tion. It is founded on the conviction that it is better to have the free play of

forces do the weeding-out than to expect loquacious conference rooms or

integral planning cycles to do the work (cf. V. Ostrom 1973; Sunstein 2008;

Surowiecki 2004).

Following and combining such tracks, urban governance in a particular

area may distinguish itself from other areas, which is not to say that it will be

completely distinctive. There are, for instance, almost always planners and

other policy specialists active in urban governance, and there is bound to be

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

560 Urban Affairs Review 50(4)

a minimum of rules and regulations for urban planning almost everywhere.

Figure 1 abstracts from these commonalities and focuses on the divergence in

urban governance: comparatively strong tendencies to involve real decision

makers or ordinary citizens, to rely on selective choice or integrative delib-

eration. Four ideal-typical combinations of such tendencies will be discussed

below, but beforehand, it should be noted that these are indeed ideal types to

which realities can be compared but never reduced. Some urban areas show

not a lot of these tendencies—think about some French departments where

official rule tends to dominate—while other areas display a great deal, pos-

sibly even a variety of types. But to detect such idiosyncrasies, we first need

more analytical clarity.

The Urban Market

Combining a distinctive individual citizens orientation (B) with a marked

leaning to a selective mode of choice (D) gives us, in Figure 1, the ideal type

of the “urban market” (II). While market-like governance was surely boosted

by Anglo-American New Public Management, which has gained a lot of

ground over the past two decades, it cannot be simply reduced to it. Already

in the early 1960s, well before the advent of New Public Management as we

now know it, V. Ostrom demonstrated how metropolitan governance in the

United States was strongly predicated on transactional relations between

decentered suppliers of public goods on one hand and individualized choices

of citizens on the other (V. Ostrom, Tiebout, and Warren 1961; cf. Keating

1991; Toonen 2010). Individual choices of this type are not free of socioeco-

nomic pressures. The urban market tends to be selective rather than compre-

hensive (choices shall be made).

The contemporary customer choice arrangements described by Pierre

(2000) connect to this variant, as do the many forms of comparative assess-

ment in which public goods, services, policies, and providers are being rated,

ranked—and, thus, indirectly steered—by citizens cum consumers. The pub-

lic domain is viewed here as a marketplace, and the citizen is seen as the

central, demanding actor vis-à-vis a scattered supply of public goods and

services. The urban market hinges on direct consumer input and critical feed-

back related to delivered output.

In urban-market governance, citizens “vote” with their feet, hands, purses,

Facebook likes, and other electronic thumbs-up or thumbs-down. The actors

competing for these “votes” can not only be exogenous providers, but they

can also be citizens themselves. An example is provided by the town of

Dordrecht in the Netherlands with its participatory budgeting project Citizens

Turn! This initiative allows ordinary citizens to submit proposals for their

neighborhood, which are then trimmed down to just a few winning proposals

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

Hendriks 561

in voting procedure that is competitive and exclusionary at the same time

(Boluijt, Drosterij, and Hendriks 2012a). Boroughs in the city of Berlin pro-

vide similar choice mechanisms, embedded in a wider process of participa-

tory budgeting (Franzke 2007).

Electronic “information markets” as described by Surowiecki (2004, pp.

79–83) and Sunstein (2008, pp. 103–45)—in which many individual “bets”

are aggregated to a collective assessment—are not (yet) common in urban

governance. In theory, they can help in predicting, for instance, the use of a

new metro line, the cost of developing a new town square, or other urban

developments about which people have dispersed independent and real bits

of information.

The Urban Regime

The ideal type of the urban regime (I) combines a distinctive focus on real

decision makers (A) with a selective way of making deals and taking deci-

sions in the urban arena (D). In Stone’s version of an urban regime, the selec-

tion mechanism is highly implicit and quasi-evolutionary. Only a small

selection of societal and political elites—the strongest parties with the most

scarce and vital resources—“survive” the process of regime formation. They

seek each other out and enter into a rather exclusive and long-standing joint

venture, as the black political elite and the white business elite did in Atlanta.

Not only their alliance but also their agenda was selective (Stone 1989). For

a European example, we can look at the joint venture of “port barons” and

political top dogs that drove the immense growth of the Port of Rotterdam in

the postwar period (C. Wagenaar 1992).

In the Dutch QGG research, a version of an urban regime was found in the

case of Brainport Eindhoven, with a select gathering of urban government

officials and top dogs from major knowledge institutions and knowledge-

intensive businesses (most notably Philips) collaborating to boost the knowl-

edge economy in the Eindhoven area (Van Ostaaijen and Schaap 2012). The

Brainport regime has a marked elitist and instrumentalist focus in common

with the urban regime type found in places like Atlanta and Chicago (Stone

1989, 2006) but is explicitly “tripartite” where the American cases typically

bring two different worlds together. The quasi-corporatist, tripartite twist to

the urban regime is also visible in another European case: the Northern-Milan

Development Agency working on the basis of a three-party agreement, forged

in the 1990s, between state government, trade unions, and private-sector rep-

resentatives (Gualini 2005).

An urban regime can be highly productive, but the social and political

legitimation tends to be problematic, as Stone (1989) frankly acknowledged.

There is little room for ordinary citizens, but this is not to say that the urban

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

562 Urban Affairs Review 50(4)

regime only serves the interests of the city’s top dogs; their connected power

is not so much “power over” (controlling) but rather “power to” (productive),

and this may well be in the citizen’s best interest—at least, according to urban

regime theory (cf. DiGaetano and Klemanski 1993; Harding 1994; Lauria

1997; Stoker 1995; Stone 1989).

The Urban Trust

Combining a strong focus on a decision-making elite (A) with an emphasis

on a more integrative and deliberative approach (C) produces the heuristic

type of the urban trust (III). The urban trust brings “trustees” of a wider range

of interested parties together in a more communicative and inclusive fashion

than the urban regime. An apt illustration is the Let’s Make This Town

Together initiative in the Dutch city of Zwolle (Boluijt, Drosterij, and

Hendriks 2012b). The definition of “Together” accommodates a wide array

of constituencies and institutions. One of these is the city library, an institu-

tion that would be an unlikely candidate for participation in an American-

style urban regime. Citizens, however, remain in the background; much is

expected from cooperating trustees.

The urban trust finds a good breeding ground in the constitutional setting

of the European Rhineland, where consensualism, consociationalism, power-

dispersal, and power-sharing are strongly institutionalized (Daalder 1987;

Lijphart 1999). Another good illustration is the ROM (Ruimtelijke Ordening

en Milieu) network developed in and around the Belgian city of Ghent (De

Rynck and Voets 2005). This is typically a multilevel and multisectoral net-

work, connecting not only leading figures of various levels of government

with responsibilities in the canal area of Ghent but also many stakeholders

with economic, environmental, and spatial interests. The name of the game is

“integral planning,” and the approach is comparatively inclusive. The ROM

initiative has won a number of prizes in spatial planning, and is generally

perceived as a successful cooperative, but De Rynck and Voets (2005, pp.

177–82) also noted that citizens were far removed from the deliberations,

which tended to “fly over their heads” at a high level of abstraction and

technicality.

The urban trust model may find fertile soil in the European Rhineland, but

it is not confined to it. The SPCs (Strategic Planning Committees) developed

in a city like Dublin, Ireland, come remarkably close to its logic (Callahan

2005; Loughlin 2011). SPCs can work for various purposes (economic devel-

opment, transport, housing, environmental and general services), but they are

always composed of political representatives (two-thirds local councilors,

9–12 members) and representatives of various social interests (one-third

societal stakeholders, 3–4 members). This governance model reaches out to

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

Hendriks 563

civil society, but it does not come as close to the citizenry as the urban plat-

form aspires to come (Noveck 2009; H. Wagenaar and Duiveman 2012).

The Urban Platform

In the ideal type of the urban platform (IV), a marked emphasis on integration

and deliberation (C) is combined with a strong focus on ordinary citizens in

neighborhoods and the city at large (B). The public realm is envisioned as a

wide and open platform on which everyone—emphatically also the individ-

ual citizen—can have a say. The urban platform revolves around dialogue,

not contest; it institutionalizes a comprehensive rather than exclusive

approach to alternatives and collective decisions (cf. Box 1998; Fung 2004;

Goodin 2008).

Dutch towns know many variations on this theme. A nice example from

the QGG research is the Neighborhood Tables initiative in Breda, a citizen

participation project involving residents, housing corporations, and the local

council. Neighborhood Tables aim to draw policy makers and citizens closer

together and to improve mutual understanding, general levels of knowledge,

and mutual perceptions in neighborhoods where such Tables are held. The

Neighborhood Tables initiative suits the increasing consideration given to

“interactive communication” and “appreciative inquiry” in this town (Van

Ostaaijen and Drosterij 2011). It can be viewed as an expression of the so-

called “third generation of citizen participation,” which brings government

officials and citizens together with an increasing emphasis on the latter (cf. H.

Wagenaar and Duiveman 2012).

Neighborhood Tables are a smaller-scale alternative to the Neighborhood

Councils that have developed in many cities, ranging from Portland and Los

Angeles in the United States to Lille and Munich in Europe (Berry, Portney,

and Thompson 1993; Cole 2011; Musso et al. 2006). Munich is an example

of a city that has widely and consistently invested in the urban platform not

only through its Neighborhood Councils but also through the “Munich

Forum,” an open platform for deliberation about the entire city and its neigh-

borhoods since 1968, when grassroots protest triggered the establishment of

such an arrangement (Hendriks 1999a, pp. 169–72). More recently, Melbourne

has developed a Planning Wiki, integrating new web-based technology and

social media, in an attempt to generate wider public input and creativity in

urban design (Noveck 2009).

Whether such shifts in governance actually manage to get any closer to

good governance is, of course, another matter. The idea that governance is

good in itself—and that, therefore, governance and good governance are

practically synonymous—is a fallacy: Varieties of governance may work

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

564 Urban Affairs Review 50(4)

well in the urban domain but need not do so at all. This requires critical

reflection, informed by essential quality standards.

Good Urban Governance: Core Values

The “goodness” of governance cannot be taken for granted but should time

and again be assessed in connection to a solid frame of reference. This goes

for the urban domain as well as for any other field of public concern (Ahrens,

Weingarth, and Caspers 2010; Andrews 2010; Mulgan 2006).

The simplest definition of good governance is: governance that qualifies

as good for some reason. An instance of urban governance could be qualified

as good to the extent in which the pertaining working arrangements operate

well with regard to essential quality standards. But what are these? Debates

in public administration on this issue tend to be wide-ranging, mentioning a

great many things, often in a not very systematic fashion. Here are just a few

examples:

•• The United Nations (United Nations Development Programme [UNDP

1977]) have been using their own set of quality standards for quite

some time: participation; strategic vision, rule of law; transparency;

responsiveness; consensus orientation; equity building; accountabil-

ity; effectiveness and efficiency.

•• The Council of Europe (2008) defined “Twelve Principles of Good

Democratic Practice at Local Level” (comprising in fact more than 12

principles): fair conduct of elections, representation, and participation;

responsiveness; efficiency and effectiveness; openness and transpar-

ency; rule of law; ethical conduct; competence and capacity; innova-

tion and openness to change; sustainability and long-term orientation;

sound financial management; human rights; cultural diversity and

social cohesion; accountability.

•• The Dutch Ministry of the Interior and Kingdom Relations (Ministerie

van BZK 2009) drafted a Good Governance Code, defining seven core

qualities (which comprise, all in all, 11 standards): openness and

integrity, good service provision, participation, goal-orientedness and

efficiency, legitimacy and justice, self-correction and learning capac-

ity, accountability.

Appreciating Good Governance: A Catalogue of Values

Here, a somewhat different approach is taken, informed by the Dutch QGG

research (see Note 1; Hendriks and Drosterij 2012), in addition to academic

debate on quality in democracy and the rule of law (Bovaird 2005; Drosterij

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

Hendriks 565

Table 1. Good Governance Values Catalogue.

Input Values Output Values System Values

(What Enters the (What Leaves the (What Constitutes the

System) System) System)

Democracy as responsive Democracy as effective Democracy as resilient

‘rule by the people’ ‘rule for the people’ ‘rule of the people’

Core Value: Core Value: Core Value:

Responsiveness Effectiveness Resilience

Related input values: Related output values: Related system values:

Representation, rapport, Productiveness, Dynamic stability, self–

participation, access, efficiency, added value, regulation,

openness innovation, problem– sustainability,

solving adaptability, cohesion in

diversity

Rule of Law/Rechtstaat as Rule of Law/Rechtstaat as

‘rule by the law,’ ‘rule for the law’ ‘checks and balances’

Core Value: Core Value:

Procedural justice Counterbalance

Related process values: (*) Related system values:

Due process, lawfulness, correctness, Countervailing powers and

predictability; integrity and civility; responsibilities, checks

transparency and accountability; proportionality and balances, oversight

and fair play; impartiality and equality of rights and surveillance,

supervision and control

*These are called process values, because lawfulness, correctness, fair play, and the like

pertain to the entire process that—in systems theory—connects inputs to outputs. The over-

arching value of procedural justice is also in essence a process value—not confined to either

the input side or the output side of governance.

2008; Haus, Heinelt, and Stewart 2005; Heinelt, Sweeting, and Gemitis 2006;

Hendriks 2010; Mulgan 2006; Pierre 2009; Rothstein and Teorell 2008). This

has led to the construction of a good governance values catalogue, covering

five core values: responsiveness, effectiveness, procedural justice, resilience,

and counterbalance. Table 1 helps to clarify how these values interlock.

The good governance values catalogue collapses many of the specific val-

ues mentioned above into fewer and more fundamental categories. This is

done not only because the human mind can deal better with a smaller number

of items but also and primarily because the good governance debate is in dire

need of the second step in the evolutionary process of “variation and

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

566 Urban Affairs Review 50(4)

selection.” Besides a more systematic selection, this requires a consistent

focus on values of good governance, not to be confused with values of good

politics (cf. Hendriks 1999b; Mulgan 2006). Substantial values, such as free-

dom, equality, solidarity, physical and social security, poverty-redemption,

peace-keeping, sustainability, and the like, are surely relevant to normative

political debate, but good governance values pertain to something else. They

are not so much about the “good life,” but rather about the “good order,” the

sound setup and the proper ground rules of the operating system.4

There are different ways of discussing the catalogue of values. We could

follow the columns distinguishing between input, output, and system values.

Alternatively, we could follow the rows distinguishing between values

inspired by democratic theory (the upper half of the table), and by theories of

the Rechtsstaat and the rule of law (the lower half). Below, the two routes are

combined, aspiring to call due attention to

• Responsiveness and effectiveness: the dominant values in contempo-

rary thinking about good governance in terms of inputs and outputs

(what goes in and what comes out); undeniably important, but there is

more to good governance;

• Procedural justice: a container concept for process values relating

to the entire chain of actions connecting inputs and outputs in

governance;

• Resilience and counterbalance: classic system values, nowadays

somewhat subdued, pertaining to the constitution of the system as

such (independently of what goes in, comes out, or proceeds in

between).

Responsiveness and Effectiveness

Democratic theory often refers to Lincoln, who in his famous Gettysburg

Address of 1863 declared that democracy as rule of the people (the contrac-

tion of demos and kratos) ought to be rule by the people and rule for the

people as well. Following this line of thinking, Scharpf (1997, 1999) observed

that democratic governance, whether of a direct or indirect kind, must be

prompted by the people so as to acquire “input legitimacy” and must produce

added value for the people so as to acquire “output legitimacy.”

According to Putnam (1993), good democratic governance “not only con-

siders the demands of its citizenry (that is, is responsive) but also acts effica-

ciously upon these demands (that is, is effective)” (p. 63). A governance

model may be considered responsive to the degree and way in which it has

organized representation, participation, accessibility, and openness. A model

of governance may be considered effective to the degree and way in which it

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

Hendriks 567

shows an ability to actually do things, solve problems, and deliver value for

money.5

In the urban domain, responsiveness and effectiveness are relevant values

that are often pursued in programs aiming to further urban governance. One

of the cases in the Dutch QGG research, the Eindhoven Brainport project,

explicitly aimed to accomplish added (economic) value for the urban region

(Van Ostaaijen and Schaap 2012). It was mostly focused on output legiti-

macy, and not so much on input legitimacy, just like the urban regime cum

growth coalition was that Stone (1989) had witnessed in Atlanta. In the case

of Breda, it was the other way around. There, Neighborhood Tables were

established to improve openness and rapport with the citizens on the input

side of the urban governance model. For the establishment of Neighborhood

Councils in cities like Los Angeles and Lille, this was also the prime concern

(Cole 2011; Musso et al. 2006; Van Ostaaijen and Drosterij 2012).

Procedural Justice

Good governance amounts to more than gratifying the citizenry, let alone a

momentary majority of citizens. This is central to the idea of the Rechtsstaat

or the “rule of law,” which complements the idea of democracy as the “rule

of the people.”6

Regarding process values, we may think of the officially-prescribed

Algemene Beginselen van Behoorlijke Bestuur (General Principles of

Appropriate Administration) in the Netherlands or similar process values

(accountability, transparency, ethical conduct, human rights, rule of law)

included in the good governance code issued by the Council of Europe

(2008). The values catalogue presented in Table 1 lists the crucial ones under

the umbrella term “procedural justice,” bringing together more legal (lawful-

ness, accountability, equal rights) and more interactionist (correctness, integ-

rity, civility) types of values. Rothstein and Teorell (2008) considered one

element out of this set—impartiality—as the essence of good governance.

However important this element is in and of itself, relying on impartiality

alone would undervalue other essential standards of procedural justice (cf.

Esaiasson 2010; Tyler and Darley 2000; Tyler and Huo 2002).

Procedural justice is no less a core value for good governance in the urban

domain than responsiveness or effectiveness. Those involved in urban gover-

nance have legitimate procedural expectations and rights, and they are fully

entitled to demand respect to them, even if urban governance is said to be

working by and for the demos at large. Especially where formal political

rights and deeply-felt social norms concerning due process converge—as in

principles such as fair play, equality, and proportionality—sensitivity to this

dimension of good governance tends to be well developed among the

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

568 Urban Affairs Review 50(4)

citizenry. Against this background, it is remarkable that only one case out of

the eight cases in the Dutch QGG study specifically prioritized process val-

ues in the attempts to improve urban governance. Only for the Neighborhood

Tables, initiative in Breda was due process a top priority (Van Ostaaijen and

Drosterij 2012).

Resilience and Counterbalance

Good governance is not only related to what goes in, comes out, or proceeds

in between, but it is also, and essentially, related to the way in which the

overarching system as such is constituted, and the way in which the constitu-

tional whole of offices, organs, positions, and relations is assembled—

robustly or not (cf. V. Ostrom 1982; Toonen 2010).

Some parts of democratic theory tend to stress the importance of resil-

ience, more specifically, the self-supporting, dynamic stability of the demo-

cratic system. A resilient, dynamically-stable democracy invests

systematically in its ability to remain standing when pressurized and to

remain united when divided, “E Pluribus Unum” (Stassen 1942). In postwar

Germany, for example, this was reflected in the notion of the wehrhafte

Demokratie: the kind of democracy that would keep centrifugal forces in

check with centripetal institutions (Almond and Verba 1980). Constitutional

thinking about the Rechtsstaat in continental Europe and the rule of law in

Anglo-American discourse tends to be more focused on systematic counter-

balance and the separation of powers. Good governance, here, is all about the

balancing of interests, the institutionalization of countervailing forces and

responsibilities, of actors, offices, and organs keeping each other in check

(Alexander 2001; Rosanvallon 2008).

System values, such as resilience and counterbalance, are often associated

with the modern state while their true cradle is really the urban polity. As

noted in earlier sections, the seeds of constitutional thinking about robust rela-

tions had been sown in Republican Rome and other European city-states many

centuries before the advent of the modern state. In thinking about good urban

governance today also, we should be paying close attention to system values.

There is every reason to do so. Cleavages and tensions between different

groups of people characterize the urban realm (Duyvendak, Hendriks, and van

Niekerk 2009; Putnam 2007). The urban world is full of planning disasters and

policy fiascos, demonstrating how the arrangement of proper checks and bal-

ances is debatable, to say the least (Flyvbjerg 2003; Hall 1982).

In the Dutch QGG study, only one out of eight cases gave top priority to

system values; the Let’s Make This Town Together initiative in Zwolle was

first and foremost dedicated to furthering resilience (in Dutch: veerkracht) of

the urban governance system. Governance reforms in the cases of Almere

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

Hendriks 569

and Dordrecht were only secondarily geared to system values; furthering

practical performance—improving input and output legitimacy—was

deemed more important here (Hendriks and Drosterij 2012).

The constitution of urban governance is impacted by the establishment of

new regulatory powers, decentered offices, supervisory arrangements like

urban audit offices, municipal ombudsmen, and the like. Issues of supervi-

sion and control are no less important for the urban arena than they are for the

corporate world, where such issues are nowadays hotly debated under the

title of “corporate governance” (Daily, Dalton, and Cannella 2003; Denis and

McConnell 2003). Bringing the constitution back in—not only in conceptual

discourse on good democratic governance but also in practical attempts to get

closer to this in the urban realm—seems to be a challenge for years to come.

Conclusion: Bringing the Democratic Rule of Law

Back In

If we were to paint a contemporary Buon Governo in Città, inspired by

Lorenzetti’s famous panels in Siena, what should we highlight as essential?

This article suggests the following answer: responsiveness, effectiveness,

procedural justice, resilience, and counterbalance. These can be viewed as

core values of good urban governance. (They could even be depicted by a

creative artist. The murals and stained glass windows in some of the older

European town halls might serve as sources of inspiration.)

An idealist might argue that urban governance should always strive for

flawless performance on all the five core values of good urban governance. A

more realistic approach, advocated in this article, would allow a situation-

sensitive logic of “step-dancing” (Hood 1998), alternating heightened atten-

tion to particular values, in combination with a sense of “good enough

governance” (Grindle 2007)—acceptable quality levels need to be observed

all around, but not everything can be perfect all the time.

There are several ways of promoting good urban governance values or to

attempt making improvements to some of them. Many arrangements are being

tried and tested in practice, as the various cases mentioned in the previous sec-

tions testify. Varied shifts in urban governance, divergent movements on the

conceptual map depicted in Figure 1, can be detected in the real world.

Governance theory is supposed to be indifferent as to the specifics of gover-

nance reform: moving this way or that way, more or less citizen-oriented, more

or less deliberative, in the theory of governance, it does not really matter—“if

only things work well.”

Although the pragmatic philosophy accompanying governance theory

appears to be refreshing, this article has also pointed out two problems with

this approach. First, governance discourse does not always adhere to the

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

570 Urban Affairs Review 50(4)

maxim of pragmatism and ideological indifference, and often implicitly

assumes that horizontal methods are better than vertical ones, and nonformal

methods better than formal ones. It is not always acknowledged that “govern-

ment” can be of crucial importance within “governance” or that networks

often develop “in the shadow of hierarchy” (Scharpf 1997).

Second, “if only things work well” is often taken in a singular sense. Pierre

(2000) was right to criticize the performance bias, the preoccupation with

instrumental norms, and the coincident neglect of wider democratic values in

thinking about governance. This is particularly noticeable in the urban realm,

where down-to-earth concerns are never far away. The argument presented

here concurs with Pierre’s appeal to “bring democracy back in,” provided

that this is not limited to bringing the voice of the citizen back in. Surely,

citizen-responsive governance is valuable, but there is more to good urban

governance than that.

This article has made a case for bringing the democratic rule of law—

broadly defined, with all the values attached—back into thinking about good

(urban) governance. Only then can we provide a well-founded and advanced

answer to the question if and how urban governance of whatever kind will

also imply good governance.

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research,

authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Funding

The author(s) received no financial support for the authorship, and/or publication of

this article. The underlying QGG research project was financed by Nicis Institute for

Urban Research in the Netherlands.

Notes

1. In addition to the international literature, this article builds on the QGG (Quest

for Good Governance) research project, financed by Nicis Institute for Urban

Research in the Netherlands. This QGG research was focused on urban gover-

nance reforms in eight Dutch cities (Amsterdam, The Hague, Eindhoven, Zwolle,

Dordrecht, Tilburg, Almere, and Breda), resulting in an edited volume (Hendriks

and Drosterij 2012) with case studies provided by a host of authors (Bram

Boluijt, Marcel Boogers, Gerard Drosterij, Robert Duiveman, Frank Hendriks,

Koen van der Krieken, Tamara Metze, Julien van Ostaaijen, Linze Schaap,

Hendrik Wagenaar, and Sabine van Zuydam). The research was guided by the

framework presented here, which was in its turn also refined by the research. The

author acknowledges all those mentioned for, thus, sharpening the understanding

of (good) urban governance. Special thanks go to Gerard Drosterij, who helped

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

Hendriks 571

to prepare earlier drafts of this argument in Dutch. The editors of Urban Affairs

Review (UAR) and two anonymous reviewers are thanked for valuable com-

ments and suggestions.

2. The governance of Republican Rome was divided over many public positions

and private parties (often families), who more or less balanced each other out.

Day-to-day governing was in the hands of two consuls, elected for just one year

at a time, who were to share power with a powerful Senate, and with assem-

blies and tribunes of the people. Classic authors, such as, Polybios and Cicero

celebrated and defended the extensive system of countervailing forces, which

was codified in Roman law but even more so in cultural norms and social codes

(Finer 1999; Macchiavelli [1513] 1998).

3. Why urban areas in the Western world? In addition to practical limitations in

terms of available research and literature, there is a more fundamental point:

What urban areas in the Western world have in common is that public issues have

to be managed within the confines of the democratic rule of law, which implies a

particular constitutional framework that does not apply to urban governance in,

say, Singapore or Beijing.

4. One could apply the metaphor of a computer here, which also needs some fun-

damental prescriptions, defined in the operating system, to function properly.

Although one should never push a metaphor too far, this one does help to see

merits and limits: A sound operating system may be the basis for good programs,

but these do not automatically result from it.

5. Dahl (1994) referred to “participation” versus “effectiveness,” and Lijphart

(1999) referred to “‘representation” versus “performance,” but to all intents

and purposes, these are all about the same thing: input legitimacy versus output

legitimacy, or, in terms of their more generic synonyms, responsiveness, and

effectiveness (cf. Hoggart and Clark 2000).

6. Forcing the issue, one could distinguish input values (“rule by the law,” or gov-

ernance that abides by, follows, respects, and internalizes the law) and output

values (“rule for the law,” or governance that expresses, operationalizes, admin-

isters, and enforces the law), but the essentials of procedural justice actually

relate to the entire process connecting inputs and outputs. Therefore, the input/

output distinction is not highlighted in Table 1 when it comes to process values.

References

Ahrens, J., R. Caspers, and J. Weingarth, eds. 2010. Good Governance in the 21st

Century. Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

Alexander, L. 2001. Constitutionalism: Philosophical Foundations. Cambridge:

Cambridge Univ. Press.

Almond, G. A., and S. Verba. 1980. The Civic Culture Revisited. Boston: Little,

Brown.

Andrews, M. 2010. “Good Government Means Different Things in Different Countries.”

Governance 23 (1): 7–35.

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

572 Urban Affairs Review 50(4)

Berry, J. M., K. E. Portney, and K. Thompson. 1993. The Rebirth of Urban Democracy.

Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Bevir, M. 2010. Democratic Governance. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.

Boluijt, B., G. Drosterij, and F. Hendriks. 2012a. “Omgaan met botsende verwacht-

ingen: Burgers aan Zet! in Dordrecht” [Dealing with Conflicting Expectations:

Citizens Turn! In Dordrecht]. In De zucht naar goed bestuur in de stad: Lessen

uit een weerbarstige werkelijkheid, edited by F. Hendriks and G. Drosterij, 31–

46. The Hague: Boom/Lemma.

Boluijt, B., G. Drosterij, and F. Hendriks. 2012b. “Samen maken we de Stad: Naar een

nieuw besturingsmodel in Zwolle” [Let's Build This Town Together: Towards a

New Steering Model in Zwolle]. In De zucht naar goed bestuur in de stad: Lessen

uit een weerbarstige werkelijkheid, edited by F. Hendriks and G. Drosterij, 79–90.

The Hague: Boom/Lemma.

Bovaird, T. 2005. “Public Governance: Balancing Stakeholder Power in a Network

Society.” International Review of Administrative Sciences 71 (2): 217–28.

Bovaird, T., and E. Löffler. 2003. “Evaluating the Quality of Public Governance:

Indicators, Models and Methodologies.” International Review of Administrative

Sciences 69:313–28.

Box, R. 1998. Citizen Governance: Leading American Communities into the 21st

Century. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Callahan, M. 2005. “Institutionalizing Participation and Governance? New

Participative Structures in Local Government in Ireland.” Public Administration

83 (4): 909–29.

Cole, A. 2011. “France, between Centralisation and Localisation.” In The Oxford

Handbook of Local and Regional Democracy in Europe, edited by J. Loughlin,

F. Hendriks, and A. Lidström, 307–30. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Council of Europe. 2008. The Strategy for Innovation and Good Governance at Local

Level. Strasbourg, France: Council of Europe.

Daalder, H. 1987. “Countries in Comparative European Politics.” European Journal

of Political Research 15:3–21.

Dahl, R. A. 1994. “A Democratic Dilemma: System Effectiveness versus Citizen

Participation.” Political Science Quarterly 109:23–34.

Daily, C. M., D. R. Dalton, and A. A. Cannella Jr. 2003. “Corporate Governance:

Decades of Dialogue and Data.” The Academy of Management Review 28 (3):

371–82.

Denis, D. K., and J. J. McConnell. 2003. “International Corporate Governance.” The

Journal of Financial and Quantitative Analysis 38 (1): 1–36.

De Rynck, F., and J. Voets. 2005. “Re-institutionalisation in the Flemish Region:

Cases of Collaborative Management.” In Urban-Regional Cooperation in the

EU: Practices and Prospects, edited by F. Hendriks, V. van Stipdonk, and P.

Tops, 163–86. The Hague: Elsevier.

DiGaetano, A., and J. S. Klemanski. 1993. “Urban Regime Capacity: A Comparison

of Birmingham, England, and Detroit, Michigan.” Journal of Urban Affairs 15

(4): 367–84.

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

Hendriks 573

Drosterij, G. 2008. Politics as Jurisdiction: A New Understanding of Public and

Private in Political Theory. Tilburg: Tilburg Univ. Press.

Duyvendak, J. W., F. Hendriks, , and M. van Niekerk. 2009. City in Sight: Dutch

Dealings with Urban Change. Amsterdam: Amsterdam Univ. Press.

Esaiasson, P. 2010. “Will Citizens Take No for an Answer? What Government

Officials Can Do to Enhance Decision Acceptance.” European Political Science

Review 2 (3): 351–71.

Finer, S. 1999. The History of Government from the Earliest Times, Parts I–III.

Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Flyvbjerg, B. 1998. Rationality and Power: Democracy in Practice. Chicago: The

Univ. of Chicago Press.

Flyvbjerg, B. 2003. Mega Projects and Risk: An Anatomy of Risk. Cambridge:

Cambridge Univ. Press.

Franzke, J. 2007. “European Experiences in Participatory Budgeting: Prioritising the

Borough Budget in Berlin-Lichtenberg.” Governance International 1:1–10.

Fung, A. 2004. Empowered Participation: Reinventing Urban Democracy. Princeton:

Princeton Univ. Press.

Goodin, R. E. 2008. Innovating Democracy: Democratic Theory and Practice after

the Deliberative Turn. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Grindle, M. S. 2007. “Good Enough Governance Revisited.” Development Policy

Review 25 (5): 533–74.

Gualini, E. 2005. “The Milan Urban Region and Local Cooperation: Framing Local

Governance by Innovating Policies.” In Urban-Regional Cooperation in the EU:

Practices and Prospects, edited by F. Hendriks, V. van Stipdonk, and P. Tops,

143–62. The Hague: Elsevier.

Hajer, M., and H. Wagenaar, eds. 2003. Deliberative Policy Analysis: Understanding

Governance in the Network Society. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Hall, P. A. 1982. The Great Planning Disasters. Berkeley: Univ. of California Press.

Harding, A. 1994. “Urban Regimes and Growth Machines: Towards a Cross-National

Research Agenda.” Urban Affairs Quarterly 29 (3): 356–82.

Haus, M., H. Heinelt, and M. Stewart, eds. 2005. Urban Governance and Democracy.

London: Routledge.

Heinelt, H., D. Sweeting, and P. Gemitis, eds. 2006. Legitimacy and Urban

Governance. London: Routledge.

Hendriks, F. 1999a. Public Policy and Political Institutions: The Role of Culture in

Urban Policy. Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

Hendriks, F. 1999b. “The Post-Industrialising City: Political Perspectives and Cultural

Biases.” GeoJournal 47 (3): 425–32.

Hendriks, F. 2010. Vital Democracy: A Theory of Democracy in Action. Oxford:

Oxford Univ. Press.

Hendriks, F., and G. Drosterij, eds. 2012. De zucht naar goed bestuur in de stad:

Lessen uit een weerbarstige werkelijkheid [The Quest for Good Governance in

the City: Lessons from Complex Realities]. The Hague: Boom/Lemma.

Hendriks, F., and J. Musso. 2004. “Making Local Democracy Work: Neighborhood-

Oriented Reform in Los Angeles and the Dutch Randstad.” In Tampering with

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

574 Urban Affairs Review 50(4)

Tradition, edited by P. Bogason, S. Kensen, and H. Miller, 39–61. Lanham:

Lexington Books.

Hoggart, K., and T. N. Clark, eds. 2000. Citizen Responsive Governance. The Hague:

Elsevier.

Hood, C. 1998. The Art of the State: Culture, Rhetoric, and Public Management.

Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Hunter, F. 1953. Community Power Structure. Chapel Hill: Univ. of Carolina Press.

Israel, J. 1995. The Dutch Republic: Its Rise, Greatness, and Fall 1477-1806. Oxford:

Oxford Univ. Press.

Keating, M. 1991. Comparative Urban Politics: Power and the City in the US,

Canada, Britain and France. Aldershot: Edward Elgar.

Kjaer, A. M. 2004. Governance. Oxford, UK: Polity Press.

Kooiman, J. 2003. Governing as Governance. London: Sage.

Lauria, M., ed. 1997. Reconstructing Urban Regime Theory: Regulating Urban

Politics in a Global Economy. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Lijphart, A. 1999. Patterns of Democracy: Government Forms and Performance in

Thirty-Six Countries. New Haven: Yale Univ. Press.

Loughlin, J. 2011. “Ireland: Halting Steps to Local Democracy.” In The Oxford

Handbook of Local and Regional Democracy in Europe, edited by J. Loughlin,

F. Hendriks, and A. Lidström, 48–67. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Lowndes, V., and C. Skelcher. 1998. “The Dynamics of Multi-organizational

Partnerships: An Analysis of Changing Modes of Governance.” Public

Administration 76 (2): 313–33.

Macchiavelli, N. (1513) 1998. The Discourses. London: Penguin Classics.

Ministerie van BZK. 2009. Nederlandse Code voor Goed Openbaar Bestuur [Dutch

Code for Good Public Governance]. The Hague: Ministerie van BZK.

Mulgan, G. 2006. Good and Bad Power: The Ideals and Betrayals of Government.

London: Penguin.

Musso, J. A., C. Weare, N. Oztas, and W. Loges. 2006. “Neighborhood Governance

Reform and Networks of Community Power in Los Angeles.” The American

Review of Public Administration 36 (1): 79–97.

Noveck, B. S. 2009. Wiki Government: How Technology Can Make Government

Better, Democracy Stronger and Citizens More Powerful. Washington, DC:

Brookings Institution Press.

Ostrom, E. 2005. Understanding Institutional Diversity. Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.

Ostrom, V. 1973. The Intellectual Crisis in American Public Administration.

Birmingham: Univ. of Alabama Press.

Ostrom, V. 1982. “A Forgotten Tradition: The Constitutional Level of Analysis.” In

Missing Elements in Political Inquiry, edited by J. A. Gillespie and D. A. Zinnes,

237–52. London: Sage.

Ostrom, V., C. M. Tiebout, , and R. Warren. 1961. “The Organization of Government

in Metropolitan Areas: A Theoretical Inquiry.” American Political Science

Review 55 (4): 831–42.

Peters, B. G., and J. Pierre. 1998. “Governance without Government? Rethinking

Public Administration.” Journal of Public Administration Research and Theory

8 (2): 223–43.

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

Hendriks 575

Pierre, J., ed. 2000. Debating Governance: Authority, Steering and Democracy.

Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Pierre, J. 2005. “Comparative Urban Governance: Uncovering Complex Causalities.”

Urban Affairs Review 40 (4): 446–62.

Pierre, J. 2009. “Reinventing Governance, Reinventing Democracy?” Policy &

Politics 37 (4): 591–609.

Pierre, J., and B. G. Peters. 2000. Governance, Politics and the State. London:

Palgrave Macmillan.

Pietrancosta, A. 2009. Enforcement of Corporate Governance Code: A Legal

Perspective. Tilburg: Tilburg Univ. Press.

Putnam, R. D. 1993. Making Democracy Work: Civic Traditions in Modern Italy.

Princeton: Princeton Univ. Press.

Putnam, R. D. 2007. “E Pluribus Unum: Diversity and Community in the 21st

Century.” Scandinavian Political Studies 30 (2): 137–74.

Rhodes, R. A. W. 1996. “The New Governance: Governing without Government.”

Political Studies 44:652–67.

Rhodes, R. A. W. 1997. Understanding Governance: Policy Networks, Governance,

Reflexivity and Accountability. Buckingham: Open Univ. Press.

Rhodes, R. A. W. 2000. “Governance and Public Administration.” In Debating

Governance, edited by J. Pierre, 54–90. Oxford: Oxford Univ. Press.

Rhodes, R. A. W. 2007. “Understanding Governance: Ten Years On.” Organization

Studies 28 (8): 1243–64

Rosanvallon, P. 2008. Counter-Democracy: Politics in the Age of Distrust. Cambridge:

Cambridge Univ. Press.

Rothstein, B., and J. Teorell. 2008. “What Is Quality of Government? A Theory of

Impartial Government Institutions.” Governance 21 (2): 165–90.

Scharpf, F. W. 1997. Games Real Actors Play: Actor Centered Institutionalism in

Policy Research. Boulder: Westview.

Scharpf, F. W. 1999. Governing in Europe: Effective and Democratic? Oxford:

Oxford Univ. Press.

Stassen, H. E. 1942. “E Pluribus Unum” [Out of Many, One]. Public Administration

Review 2 (3): 187–94.

Stoker, G. 1995. “Regime Theory and Urban Politics.” In Theories of Urban Politics,

edited by D. Judge, G. Stoker, and H. Wolman, 54-72. London: Sage.

Stoker, G. 1998. “Governance as Theory: Five Propositions.” International Social

Science Journal 155:17–28.

Stoker, G. 2000. “Urban Political Science and the Challenge of Urban Governance.”

In Perspectives on Governance, edited by J. Pierre, 91–109. Oxford: Oxford

Univ. Press.

Stoker, G. 2011. “Was Local Governance Such a Good Idea? A Global Comparative

Perspective.” Public Administration 89 (1): 15–31.

Stone, C. N. 1989. Regime Politics: Governing Atlanta 1946-1988. Lawrence:

University Press of Kansas.

Stone, C. N. 2006. “Power, Reform, and Urban Regime Analysis.” City & Community

5 (1): 23–38.

Downloaded from uar.sagepub.com by guest on June 24, 2014

576 Urban Affairs Review 50(4)

Sunstein, C. 2008. Infotopia: How Many Minds Produce Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford

Univ. Press.

Surowiecki, J. 2004. The Wisdom of Crowds: Why the Many Are Smarter than the

Few. London: Abacus.

Swyndegouw, E. 2005. “Governance Innovation and the Citizen: The Janus Face of

Governance-beyond-the-State.” Urban Studies 42 (11): 1991–2006.

Toonen, T. A. J. 2010. “Resilience in Public Administration: The Work of Elinor

and Vincent Ostrom from a Public Administration Perspective.” Public

Administration Review 70 (2): 193–202.

Tyler, T., and J. Darley. 2000. “Building a Law-abiding Society, Taking Public Views

about Morality and the Legitimacy of Legal Authorities into Account When

Formulating Substantive Law.” Hofstra Law Review 28:482–97.

Tyler, T., and Y. J. Huo. 2002. Trust in the Law: Encouraging Public Cooperation

with the Police and Courts. New York: Russell Sage.

Uitermark, J., and J. W. Duyvendak. 2008. “Citizen Participation in a Mediated Age:

Neighborhood Governance in the Netherlands.” International Journal of Urban

and Regional Research 32 (1): 114–31.

United Nations Development Programme. 1977. Governance for Sustainable Human

Development. New York: United Nations Development Programme.

Van Ostaaijen, J., and G. Drosterij. 2012. “Tussen woorden en daden: De Bredase

wijktafels en de vraag naar goed bestuur” [Between Words and Deeds:

Neighborhood Tables in Breda and the Demand for Good Governance]. In De

zucht naar goed bestuur in de stad: Lessen uit een weerbarstige werkelijkheid,

edited by F. Hendriks and G. Drosterij, 47–62. The Hague: Boom/Lemma.

Van Ostaaijen, J., and L. Schaap. 2012. “De legitimiteit van regionale samenwerking:

Het regime Brainport” [The Legitimacy of Regional Cooperation: The Brainport

Regime]. In De zucht naar goed bestuur in de stad: Lessen uit een weerbarst-

ige werkelijkheid, edited by F. Hendriks and G. Drosterij, 91–108. The Hague:

Boom/Lemma.

Wagenaar, C. 1992. Welvaartsstad in wording: De wederopbouw van Rotterdam

1940-1952 [Welfare State in the Making: The Reconstruction of Rotterdam

1940-1952]. Rotterdam: NAi Uitgevers.

Wagenaar, H., and R. Duiveman. 2012. “De kwaliteit van een stadswijk: Good gover-

nance door stedelijke daadkracht in Den Haag” [The Quality of an Urban Quarter:

Good Governance through Vigor in The Hague]. In De zucht naar goed bestuur

in de stad: Lessen uit een weerbarstige werkelijkheid, edited by F. Hendriks and

G. Drosterij, 63–78. The Hague: Boom/Lemma.

Author Biography

Frank Hendriks is a professor of comparative governance at Tilburg University. His

research focuses on the analysis, assessment, and comparison of democratic gover-

nance at the national, subnational, and urban-regional level. He is the author of Vital

Democracy: A Theory of Democracy in Action, Oxford University Press, 2010, and

coeditor of the Oxford Handbook of Local and Regional Democracy in Europe,

Oxford University Press, 2011 (with John Loughlin and Anders Lidström) and City in

Sight: Dutch Dealings with Urban Change, Amsterdam University Press, 2009 (with

Jan Willem Duyvendak and Mies van Niekerk).

View publication stats

You might also like

- Stuvia 3203824 Strategic Compensation in Canada 7e Parbudyal Singh Richard Long Test BankDocument130 pagesStuvia 3203824 Strategic Compensation in Canada 7e Parbudyal Singh Richard Long Test BankDuc Gia Nghi NguyenNo ratings yet

- Understanding Smart Cities An Integrative FrameworDocument10 pagesUnderstanding Smart Cities An Integrative FrameworCarina AraujoNo ratings yet

- CITIES AND THEIR GURUS The Role of Superstar Consultants in Post - Political Urban GovernanceDocument20 pagesCITIES AND THEIR GURUS The Role of Superstar Consultants in Post - Political Urban GovernanceFala RafaNo ratings yet

- FOUR MODES OF NEIGHBOURHOOD GOVERNANCE - The View From Nanjing, China - Wang - 20Document53 pagesFOUR MODES OF NEIGHBOURHOOD GOVERNANCE - The View From Nanjing, China - Wang - 20suvanshNo ratings yet

- The Smart City How to Evaluate Performance 1Document17 pagesThe Smart City How to Evaluate Performance 1Abdurahman AL FurjaniNo ratings yet

- Status PaperDocument29 pagesStatus PaperSreekanth SatheeshNo ratings yet

- Vertigo: Madjid ChachourDocument37 pagesVertigo: Madjid ChachourWalid BeddiafNo ratings yet

- What People Say Re I C Inquiry ActionDocument7 pagesWhat People Say Re I C Inquiry ActionMariaNo ratings yet

- Cho Et Al 2015 Urban Space FrameworkDocument23 pagesCho Et Al 2015 Urban Space FrameworkAlexander TeohNo ratings yet

- Integral City Inquiry and Action: Designing Impact for the Human HiveFrom EverandIntegral City Inquiry and Action: Designing Impact for the Human HiveNo ratings yet

- Grin Et Al (2017) Sustainability Transitions and the CityDocument9 pagesGrin Et Al (2017) Sustainability Transitions and the Citymirta.dia.sokhnaNo ratings yet

- Professional PracticeDocument7 pagesProfessional Practiceangel hofilenaNo ratings yet

- 1 s20 S2664328623000670 Main - 230818 - 185322Document17 pages1 s20 S2664328623000670 Main - 230818 - 185322fabioesaputNo ratings yet

- Foundations For Smarter CitiesDocument11 pagesFoundations For Smarter CitiesalmaniusNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument8 pagesAnnotated BibliographyANGELICA MAE HOFILEÑANo ratings yet

- SmartGovernanceintheContextofSmartCities_ALiteratureReviewVialePereireetal.2018Document40 pagesSmartGovernanceintheContextofSmartCities_ALiteratureReviewVialePereireetal.2018kovacsipeksegNo ratings yet

- Tactical Urbanism Short Term Action For Long Term ChangeDocument3 pagesTactical Urbanism Short Term Action For Long Term ChangeÖmer SuvariNo ratings yet

- Gentrification and Everyday DemocracyDocument22 pagesGentrification and Everyday DemocracyNikos KarfakisNo ratings yet

- Burns and Welker - 2022 Urban StudiesDocument17 pagesBurns and Welker - 2022 Urban StudiesMarina WertheimerNo ratings yet

- Visualising The Design of ConditionsDocument16 pagesVisualising The Design of ConditionsZahraNo ratings yet

- Periurbanization in IndiaDocument2 pagesPeriurbanization in IndiaAksa RajanNo ratings yet

- Regenerative Mobility: Disruption and Urban EvolutionDocument15 pagesRegenerative Mobility: Disruption and Urban EvolutionIEREKPRESSNo ratings yet

- Urban Form Sustainability & Urban Design Dimensions: Report TitleDocument19 pagesUrban Form Sustainability & Urban Design Dimensions: Report TitleRawand AkreyiNo ratings yet

- Integrating Slums in CitiesDocument59 pagesIntegrating Slums in CitiesDhruv MudgalNo ratings yet

- Research Proposal (Behroz)-3Document25 pagesResearch Proposal (Behroz)-3Nabeeha TariqNo ratings yet

- Representations Of, The "Poor" and "Pro-Poor" Concerns That Happen Within TheDocument3 pagesRepresentations Of, The "Poor" and "Pro-Poor" Concerns That Happen Within TheThomas OommenNo ratings yet

- Governing The Smart CityDocument17 pagesGoverning The Smart Cityaprendiz777No ratings yet

- Knappe (2020)Document25 pagesKnappe (2020)fetta.leilaNo ratings yet

- Article 1Document10 pagesArticle 1RiiNo ratings yet

- Thinking About Cities Relationally 1Document8 pagesThinking About Cities Relationally 1dabsyellNo ratings yet

- Urban Des. Methods & ELEMENTS OF URBAN DESIGN (Autosaved)Document52 pagesUrban Des. Methods & ELEMENTS OF URBAN DESIGN (Autosaved)NeanderthalNo ratings yet

- Annotated BibliographyDocument3 pagesAnnotated Bibliographyangel hofilena100% (1)

- Urban Sustainability Course Reflection PDFDocument5 pagesUrban Sustainability Course Reflection PDFniknaz alemiNo ratings yet

- Leadership For Public Value Political AsDocument20 pagesLeadership For Public Value Political AsfaztipasNo ratings yet

- Walkable City Hyderabad FinalDocument12 pagesWalkable City Hyderabad FinalPradeep RaoNo ratings yet

- An Investigation of Stakeholder Analysis in Urban DevelopmentDocument12 pagesAn Investigation of Stakeholder Analysis in Urban DevelopmentShadeedha SaradaraNo ratings yet

- Graduate Student Work: A Model For Direct and Mutually Beneficial Community-University PartnershipsDocument1 pageGraduate Student Work: A Model For Direct and Mutually Beneficial Community-University Partnershipsapi-253296477No ratings yet

- Carmona2013 PDFDocument37 pagesCarmona2013 PDFArkadipta BanerjeeNo ratings yet

- LEC6 Lopez Morales 2015 - Gentrification in The Global SouthDocument11 pagesLEC6 Lopez Morales 2015 - Gentrification in The Global Southvnchr.kNo ratings yet

- Httpsdigitalcommons Bau Edu Lbcgiviewcontent Cgiarticle 1069&context HwbjournalDocument12 pagesHttpsdigitalcommons Bau Edu Lbcgiviewcontent Cgiarticle 1069&context HwbjournalnoorNo ratings yet

- Artigo Manuel Bolivar & Albert MeijerDocument20 pagesArtigo Manuel Bolivar & Albert Meijerrosianita13No ratings yet

- Understanding Agency in Collective Action PDFDocument23 pagesUnderstanding Agency in Collective Action PDFgemma.arguellomNo ratings yet

- Cities_and_the_political_imaginationDocument14 pagesCities_and_the_political_imaginationNguyễn Vân QuỳnhhNo ratings yet

- Social UrbanismDocument5 pagesSocial UrbanismlaputaboaNo ratings yet

- Ecology of VulnerabilityDocument54 pagesEcology of VulnerabilityjadedoctopusNo ratings yet

- Design of CitiesDocument23 pagesDesign of CitiesMarilena Brastaviceanu100% (1)