JPEG XL Next-Generation Image Compression Architecture and Coding Tools

JPEG XL Next-Generation Image Compression Architecture and Coding Tools

Uploaded by

thanhmd020803Copyright:

Available Formats

JPEG XL Next-Generation Image Compression Architecture and Coding Tools

JPEG XL Next-Generation Image Compression Architecture and Coding Tools

Uploaded by

thanhmd020803Original Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

JPEG XL Next-Generation Image Compression Architecture and Coding Tools

JPEG XL Next-Generation Image Compression Architecture and Coding Tools

Uploaded by

thanhmd020803Copyright:

Available Formats

JPEG XL next-generation image compression architecture

and coding tools

Jyrki Alakuijalaa , Ruud van Asseldonk†,a , Sami Boukortta , Martin Brusea , Iulia-Maria

Coms, aa , Moritz Firschinga , Thomas Fischbachera , Evgenii Kliuchnikova , Sebastian Gomeza ,

Robert Obryka , Krzysztof Potempaa , Alexander Rhatushnyak†,a , Jon Sneyersb , Zoltan

Szabadka†,a , Lode Vandevennea , Luca Versari*,a , and Jan Wassenberga

a

Google Research Zürich, Switzerland

b

Cloudinary, Israel

ABSTRACT

An update on the JPEG XL standardization effort: JPEG XL is a practical approach focused on scalable

web distribution and efficient compression of high-quality images. It will provide various benefits compared to

existing image formats: significantly smaller size at equivalent subjective quality; fast, parallelizable decoding and

encoding configurations; features such as progressive, lossless, animation, and reversible transcoding of existing

JPEG; support for high-quality applications including wide gamut, higher resolution/bit depth/dynamic range,

and visually lossless coding. Additionally, a royalty-free baseline is an important goal. The JPEG XL architecture

is traditional block-transform coding with upgrades to each component. We describe these components and

analyze decoded image quality.

Keywords: JPEG XL, image compression, DCT, progressive

1. INTRODUCTION

JPEG1 has reigned over the field of practical lossy image compression ever since its introduction 27 years ago.

Other mainstream media encodings, especially for video and sound, have gone through several generations of

significant and well-rounded improvements during the same time period. One can ask what are the characteristics

of JPEG and the field of lossy image compression that let JPEG keep its position in spite of all the efforts so far.

We have identified two main repeating issues in previous efforts attempting to replace JPEG with more efficient

image encodings, namely, psychovisual performance in professional quality photography and the lack of gradual

migration features. We have addressed them thoroughly in our new proposal, JPEG XL, as well as generally

improved compression performance.

As an outcome of the 79th JPEG meeting in April 2018, the JPEG Committee announced the JPEG XL

activity,2 aiming to standardize a new generation of image coding that offers substantially better compression

efficiency than existing image formats (e.g. 50% size reduction over JPEG), along with features desirable for web

distribution and efficient compression of high-quality images. Proposals were due September 1, 2018, and based

on psychovisual experiments, Google’s PIK3 and Cloudinary’s FUIF4 codecs were chosen as the base framework

for JPEG XL and its further core experiments. As of July 2019, JPEG XL has advanced into the committee

draft phase, and is being prepared for circulation in ISO’s national bodies.

The authors believe that a key factor in the failure to deliver outstanding high quality psychovisual perfor-

mance in new lossy image codecs has been their tendency to target their best performance at too low bit rates,

and the coding methods not extending to higher bit rates without losing most of their efficiency along the way.

This can be most easily observed in image codecs that are derived from successful video encoding research. To

make sure that we get this right with JPEG XL, we have gathered real-world usage data on existing JPEG

utilization, and conducted independent experiments on how this could be mapped into bit rates and quality

settings in JPEG XL. We note that as a result of this focus we have aimed at higher image qualities and bit

rates than previous efforts.

† Work done while the author was at Google.

* veluca@google.com

Applications of Digital Image Processing XLII, edited by Andrew G. Tescher, Touradj Ebrahimi,

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137, 111370K © The Authors. Published under a Creative Commons

Attribution CC-BY 3.0 License · doi: 10.1117/12.2529237

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137 111370K-1

Migrating from the previous generation of media codecs to the next generation introduces a technology tran-

sition cost. Two or more incompatible encodings of the same original data need to be maintained and managed

for different clients, often increasing storage capacity cost. Occasionally some fragmentation happens already

within a single generation of codecs, contributing additionally to the transition cost. On-line transcoding, while

practical in avoiding storage costs, has disadvantages. It introduces computational cost and additional quality

and efficiency losses. These transcoding losses can be unpredictable and more dramatic if the original in previous

generation technology has been compressed lossily to the highest possible degree, because compression artefacts

of one technology are often expensive to represent by another technology. The on-line transcoding computation

time can introduce additional latency that consumes a significant fraction of the speed up that the new generation

of codecs could otherwise offer. Additional latency is unfortunate since the user experienced latency (without

compromising on the image quality) is the main driver for a new generation of lossy image compression. The

transition costs are not limited to image quality and interoperability, but organizations deploying the new coding

system may need to load test and measure backend and end-user-experienced latencies, perform security analysis,

redo capacity planning, possibly replace old equipment, and study the impact of the technology transition on

user behavior.

This paper is structured as follows. Section 2 explains the experiments that lead the authors to focus on high

quality compression. Section 3 summarizes the features that JPEG XL supports, and the motivations behind

them. Finally, Section 4 explains the general architecture of the codec, and gives details and motivations behind

some of its components.

In this paper we show that we have solved the high quality efficiency issues that previous formats, and

particularly video formats having a second life as photography formats, tend to have. We show that we have

taken several measures to reduce the migration and interoperability concerns, ranging from supporting JPEG’s

8 × 8 DCT to enabling lossless recompression of existing JPEG images — up to a point where a file that is

byte-wise identical to the original JPEG can be reconstructed from the new JPEG XL stream.

2. MOTIVATION

Historically, technological advances have not always been associated with a direct improvement in user experience.

For example, with the initial deployment of terrestrial digital television, broadcasting companies often chose

a distribution model that slightly degraded the perceived quality of the program in favor of being able to

distribute more channels. Block artefacts started to appear in fast-moving complex scenes where the previously

uncompressed signal had uncompromised good quality. The economic pressure of having more segmentation in

the market led to a slight reduction in quality.

We would like to prevent this from happening again. Our aim is to build solutions that allow us to deliver

images faster, more economically, robustly, without surprises and with a generally better perceived quality.

There was a time in the history of the internet when downgrading the quality of media was the only option

for internet transfers to happen at bearable latencies. In those times, recording devices also used to produce

images of much lower quality than they do today. However, we no longer live in that era. The average internet

connection speed around the world is steadily increasing; it was reported at 11.03Mbps in May 2019, a 20.65%

increase compared to one year before.5 Alongside, the recording and display capabilities of current phones,

cameras and monitors often have higher resolutions than an average end user can perceive. The current digital

world is evolving towards richer and highly immersive user experiences, where images are expected to look

natural. It is safe to say that optimizing for the quality of images should be regarded as a higher priority than

optimizing for the transfer speed of lower-size images.

To find out the quality of images currently used on the web, we examined the distribution of bits per pixel

(BPP) of small, medium and large JPEG images loaded by users in Google Chrome (Figure 1). The data

was recorded by telemetry; it is pseudonymous and aggregated across users. Telemetry in Chrome is opt-out

by default and can be disabled from the browser’s “Settings” menu. We approximated the number of bytes

transferred at each BPP value by multiplying the image count for a particular BPP value with the BPP value

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137 111370K-2

itself. The number of transferred bytes is important because it affects the latency and hence the user experience.

Using this estimate, we calculated that between June 1st and 28th, 2019, the average BPP (weighted by the

number of bytes transmitted with that BPP) was 2.97, 2.24 and 2.03 for small, medium and large images,

respectively. We confirmed that there was no considerable difference between mobile and desktop platforms.

This data indicates that image compression algorithms should target rich images with a relatively high BPP

values, aiming to produce 1 BPP images almost free of artefacts instead of 0.5 BPP images with artefacts that

are not too intrusive.

JPEG images loaded in Chrome (1-28 June 2019)

Image size

large

Estimated transferred bytes

medium

small

(normalized)

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Bits per pixel

Figure 1. Estimation of bytes transferred at each BPP value. BPP values are aggregated from pseudonymous data

collected by telemetry in Google Chrome. The images are classified by their smallest dimension (width or height) into

small (100–400 pixels), medium (400–1000 pixels) and large (1000+ pixels). The BPP distributions are aggregated across

all images loaded in Chrome across all platform from June 1st to 28th, 2019. The estimated counts are normalized for

each image size category. The mean for each image size is shown with dashed vertical lines. The BPP counts are obtained

from an order of billions of samples.

With these considerations in mind, JPEG XL is designed to handle high-quality images particularly well. Its

aim is serving the current and future needs of an increasingly rich media experience. Ideally, an image should

be compressed up to a point where there is no perceptible loss of quality from the original.

To assess the efficiency of JPEG XL over that of legacy JPEG in the task of encoding images with no

perceptible loss of quality, we performed the following experiment. We selected a corpus of 43 images consisting

of 12 images from imagecompression.info6 (IC dataset) and 31 images from a corpus provided by Jyrki

Alakuijala7 (J31 dataset). We chose the IC dataset because it is a standard benchmark for image compression,

and the J31 dataset because it is designed to capture semantically important low intensity features on a variety

of background colors, such as the fine structure of flower petals; our experience with image compression showed

that red, purple, and magenta backgrounds often cause high frequency features to be lost and that image quality

metrics have difficulty normalizing the differences across different background colors. We used all images from

each dataset, except for leaves iso 1600 and nightshot iso 100 from IC, which had duplicates at a different

ISO level. As the IC images are very large, we rescaled them so that the maximum dimension would be 1024

pixels. All IC images and 6 J31 hence corresponded to the large size category described above, while the other

25 J31 images corresponded to the medium size category.

We compressed each of the 43 images with legacy JPEG and JPEG XL at 24 different quality levels. For

images compressed with JPEG, we used libjpeg1.5.28 with a quality parameter of 40, 44, 48, 52, 56, 60, 64,

68, 72, 76, 80, 82, 84, 86, 88, 90, 92, 94, 95, 96, 97, 98, 99 and 100 for each of the 24 images respectively. For

images compressed with JPEG XL, we used default settings on the latest development version of the codec, and

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137 111370K-3

a distance value∗ of 8.0, 6.0, 4.0, 3.0, 2.8, 2.6, 2.4, 2.2, 2.0, 1.8, 1.6, 1.5, 1.4, 1.3, 1.2, 1.1, 1.0, 0.9, 0.8, 0.7, 0.6,

0.5, 0.4 and 0.3 for each of the 24 images respectively. For each image and compression method, we recorded

the corresponding number of bytes b and computed the bits per pixel (BPP) for that image (as 8b/(x · y) for

an image of width x and height y pixels). Finally, we decompressed the images to PNG to allow the browser to

display them without further loss.

We asked 36 healthy adult participants to indicate the lowest quality that they would find acceptable to

compress pictures with no perceptible loss of quality. All participants had normal or corrected vision and were

instructed to adjust their monitor position and chair height in order to look at the images in a comfortable and

natural position. The images were displayed on a 27” QHD monitor with a resolution of 2560 × 1440 on the

default brightness setting. All assessments were performed during daylight in a room lit by indirect sunlight.

The order of the four sets and conditions (IC JPEG, IC JXL, J31 JPEG, J31 JXL) was randomised, but always

so that the two IC sets and the two J31 sets were presented in consecutive order. For each image, the assessment

was performed by moving a slider with 25 positions to the left or to the right to adjust the compression level

of the image. The rightmost position was the starting position and it displayed the uncompressed image. The

leftmost position corresponded to the lowest compression quality and the following 23 positions corresponded to

gradually increasing compression quality levels specified above.

Out of the 3096 datapoints collected in total, we discarded 13 datapoints that were invalid due to a problem

in recording the responses that we only found after performing the experiment. As this involved a very small

number of points, we treated these as missing and discarded them.

We found that a lower BPP value was consistently selected for JPEG XL compared to legacy JPEG (Figure 2).

Pooling the results from both datasets together, the mean selected BPP was 2.09 for legacy JPEG, which is in

agreement with the Chrome statistics above. The JPEG XL distribution mode (computed using bins of size 0.1),

mean, median and skewness were 48%, 46.27%, 41.33%, and 54.7% lower than those of legacy JPEG. This effect

was preserved when splitting across sets (Figure 3) and participants (Figure 4).

350 Participant responses

JPEG

300 JXL

mode

250 mean

median

200 skewness

Count

150

100

50

0

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Bits per pixel

Figure 2. All participant responses groups by condition (JPEG and JPEG XL). The mode was obtained by grouping the

data into bins of size 0.1. The histogram bin size is 0.25. For JPEG, an additional 28 responses larger than 7, with a

maximum of 13.08, are not shown here.

∗

approximately proportional to the inverse of the quality parameter of legacy JPEG, calibrated so that a distance of

1.0 corresponds to barely perceptible artefacts under normal viewing conditions

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137 111370K-4

0.8 Participant responses

J31 JPEG

0.7 J31 JXL

0.6 IC JPEG

IC JXL

Count (normed) 0.5

0.4

0.3

0.2

0.1

0.0

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Bits per pixel

Figure 3. All participant responses grouped by condition (JPEG and JPEG XL). The histogram bin size is 0.5. The values

are normalized so that their sum per condition is 1.0/bin size = 2.0. For JPEG, the additional responses larger than 7

and not shown here sum to 0.07.

12 Mean responses per participant

JPEG

10 JXL

Number of participants

0

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7

Bits per pixel

Figure 4. Mean responses by participant and condition (JPEG and JPEG XL). For each participant, each value was

obtained by averaging over individual dataset (IC and J31), then averaging the two values. The histogram bin size is

0.25.

These results indicate that JPEG XL yields a large improvement in the representation efficiency of high-

quality images, where no perceptible loss of quality is desired. By replacing legacy JPEG with JPEG XL, it is

possible to represent such images while almost halving the required number of bits.

3. CODEC FEATURES

JPEG XL aims to be a full-featured image codec, with support for all the features that are expected by modern

image formats. Thus, JPEG XL supports an arbitrary number of channels, including alpha and depth channels;

it also allows parallel, progressive, and partial decoding. Moreover, JPEG XL supports encoding of multiple

animation frames, with different behaviours for how each frame should be blended with the previous ones: they

can be summed, replace the full frame or a sub-rectangle, or alpha-blended. JPEG XL also supports a fully

lossless mode and a responsive-by-design mode.

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137 111370K-5

Websites are viewed on a large variety of devices. The concept of responsive images addresses the different

needs of phones, tablets, computers, smart watches etc. that was traditionally addressed by having separate

website versions for different devices. The responsive image feature is however an additional requirement and

it limits the format designers’ ability to make other compromises related to image quality and decoding speed.

In JPEG XL we have overcome these limitations by having a dedicated mode, modular mode, for the most

responsive use. The modular mode uses a Haar-like integral transform that can exactly recover all subresolution

images, various color space transforms to be able to better represent existing images and achieve otherwise better

compression ratios through decorrelation, and an adaptive context model to improve the efficiency of the entropy

coding step.

The two common ways to model color vision are trichromatic theory and the opponent-process theory. The

LMS colorspace represents the response of three types of cones in the human retina that are named for their

sensitivity at long (L), medium (M), and short (S) wavelengths. In JPEG XL we base color modeling on a

possibly new hybrid color theory, where we use the opponent-process theory for L and M receptors, and the

trichromatic theory for S receptors. This allows us to control quantization and decorrelation of S receptors

separately from the L and M receptors. There is lesser spatial density of the S receptors than of the L and M

receptors, leading to a lesser information density of respective perceptual fields, and the separation allows us

to accomodate for that in how we store colors. We call this colorspace XYB, where Y is the sum of L and M

signaling after reception and X is the difference. B represents the signaling of the S receptors. In JPEG XL

we model the compression through storing the cubic root of the value over the receptor’s spectral efficiency.

While this does not exactly match receptors’ compression properties — which are modeled as hybrid-log-gamma

in some other modern efforts — it is practical since it is fast to decode and the error of the receptor response

and cubic root can be stored in the adaptive quantization field, giving roughly equally efficient quantization

performance at a higher decoding speed.

4. CODEC ARCHITECTURE

This section describes the architecture of the JPEG XL image codec, as per the committee draft of the specifi-

cation.9 An overview is given in Figure 5; the rest of the section gives more details about each component.

4.1 Integral transforms

JPEG1 is fundamentally based on the 8 × 8 DCT-II algorithm by Arai, Agui and Nakajima.10 Variable-DCT

mode of JPEG XL is still based on fundamental 8 × 8 block units, but extends this approach, and allows the use

of any bidimensional DCT-II transform whose sides are one of 8, 16, or 32† . Doing so allows further reductions

in the entropy of the image for homogeneous areas; on the other hand, it creates artefacts with longer reach, and

thus the use of these transforms requires careful selection on the encoder side.

JPEG XL also supports the use of “special” transforms that cover specific use cases:

• small DCTs of sizes 8 × 4, 4 × 8, 4 × 4, and 2 × 2 cover the opposite use case of larger transforms, such as

very heterogeneous areas, for which it is important to reduce the propagation distance of artefacts. Note

that these small DCTs are still applied on 8 × 8 blocks: as an example, for the 4 × 4 DCT, the transform

is applied on each of the four 4 × 4 areas in the 8 × 8 block; coefficients are then mixed in such a way that

DC ends up in the top-left 2 × 2 corner of the block, and a 2 × 2 DCT is applied on the DC coefficients to

obtain a single DC value. Similar techniques are used to obtain a DC value for other DCTs.

• the IDENTITY transform covers the case of some pixels in the block having very different values from

nearby pixels. As for the 4 × 4 DCT, it applies a transform to each of the four 4 × 4 areas in the 8 × 8 block,

and then proceeds with shuffling the resulting coefficients and doing a 2 × 2 DCT on the DC coefficients.

†

DCT sizes other than 8 use a different DCT algorithm, described by Vashkevich and Petrovsky11

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137 111370K-6

Figure 5. Block diagram architecture of JPEG XL.

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137 111370K-7

However, the 4 × 4 transform that is used is not a DCT. Instead, the transform computes the average of

the 4 × 4 block and, for all other values of the block except the one in position (1, 1), the difference between

the value and the one in position (1, 1). Storing deltas compared to one pixel instead of deltas from the

average avoids accumulating quantization error on the missing pixel, while choosing pixel (1, 1) instead of

(0, 0) provides slightly better compression because it is more correlated with the values in the 4 × 4 block,

on average.

• the AFV transform is also similar to 4 × 4 DCT and IDENTITY, but with a different transform for each

4 × 4 area. In particular, AFV computes a basis change similar to what a DCT does, but with specialized

basis functions that allow the 3 corner pixels to be stored separately. This allows to easily encode blocks

that have an edge barely cutting through them, which gives a very different value to a few pixels in one of

the corners.

As with JPEG, JPEG XL also has special handling of DC coefficients. For transforms that are bigger than

8 × 8, this creates a problem: there is now only one DC coefficient that spans more than one 8 × 8 block.

JPEG XL handles this situation by computing X Y

8 × 8 pseudo-DC coefficients for each X × Y transform, roughly

corresponding to the average value in each 8 × 8 block, in a reversible way. This can be done thanks to the

following key observation:

Lemma 4.1. Given N and K ≤ N , there exist non-zero constants c0 , . . . , c2N −K −1 such that the following two

procedures are equivalent for any sequence of numbers a0 , . . . , a2N −K −1 :

1. Compute an inverse DCT of size 2N −K on the array c0 a0 , . . . , c2N −K −1 a2N −K −1

2. Append 2N −K · (2K − 1) elements with a value of 0 to the a0 , . . . , a2N −K −1 array, compute an inverse DCT

of size 2N on the resulting array, and replace each of the 2N −K consecutive groups of 2K values with their

average.

For example, with N = 4 and K = 3, both procedures compute the same two values, the average of each of the

two halves of a IDCT of size 16 computed on an array with 2 nonzero entries followed by 14 zero entries.

This claim can easily proven by induction on K. By choosing K = 3, and applying the lemma along both

dimensions, this allows us to compute a value that is approximately the average of each 8 × 8 block covered by

a large DCT (computed on pixel values after ignoring some higher frequencies) that also allows to completely

recover an equivalent number of low-frequency DCT coefficients, as the first of the two equivalent procedures in

Lemma 4.1 is clearly reversible.

4.2 Entropy coding

The legacy JPEG format offers the choice of using Huffman coding12 or Arithmetic Coding13 as an entropy coder.

Both of these options come with disadvantages: Huffman coding is sub-optimal when symbol probabilities are

not exact powers of two, and Arithmetic Coding implementations typically have fairly slow decoding speed.

JPEG XL uses Asymmetric Numeral Systems14 (also known as ANS), a recently-introduced entropy coder

that achieves compression ratios similar to Arithmetic Coding, while being significantly faster during decoding.

JPEG XL encodes in a single ANS stream symbols drawn from multiple different probability distributions.

Two techniques are used to give more flexibility to encoders: distribution clustering and variable-precision

distribution encoding.

A single ANS stream may contain symbols from thousands of different distributions. Encoding all of these

distributions would use a significant amount of bits, making this choice sub-optimal for all but the longest of

streams. Thus, JPEG XL allows defining clusters of similar distributions, with a single histogram being encoded

for the whole cluster. This allows more flexibility than simply using fewer distributions, as the clustering can be

defined per-file instead of being fixed. The encoding of the clusters uses a move-to-front transform and run-length

encoding to minimize the bitstream overhead.

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137 111370K-8

To further reduce the overhead for relatively small clusters, the encoder can choose between multiple different

representations for the distributions themselves: a simple “flat” representation (that produces histograms with

roughly uniform probabilities), useful for short streams, and a representation that stores, for each probability

value, its magnitude and a variable number of less-significant bits, controllable on a per-histogram basis, that

allows to further control the tradeoff between histogram and stream size.

Finally, to reduce the number of distinct symbols that get encoded in an ANS stream, which has beneficial

effects on both histogram size and decoding speed of the entropy coder, many parts of JPEG XL use a hybrid

unsigned integer encoding scheme: values below 16 are encoded as symbols directly, while any other value is

encoded with a symbol that allows to recover the highest 2 bits set; other bits are stored uncompressed.

4.3 Color correlation

From the definition of the XYB colorspace, it follows that a fully gray pixel will be represented as a multiple

of (0, 1, 0.935669). Keeping this representation as-is is undesirable, as it transmits the luma information on two

channels at the same time. Thus, JPEG XL applies a linear transformation to pixel values immediately after

dequantization, adding a multiple of the Y channel to the X and B channels.

In particular, the default correlation factor is 0 for the X channel and 0.935669 for the B channel: this allows

to transmit luma information using the Y channel only.

However, these factors are not necessarily optimal on areas of the image with a strong chroma component

(such as, for example, fully red regions). Therefore, JPEG XL allows altering the correlation factors locally, for

tiles of 64 × 64 pixels, with a dedicated control field.

4.4 Adaptive quantization

JPEG only allows the choice of a single quantization matrix (per channel) for the whole image. This leads to

the same amount of quantization everywhere, even if some areas have more detail and may thus benefit from

increased quantization.

In JPEG XL, the choice of quantization matrix is still global (for each given integral transform); however,

this quantization matrix can be scaled locally, to decrease artefacts in more “complex” areas without increasing

the amount of bits used in other parts of the image.

Combined with a measure of loss, this allows encoders to target a roughly uniform amount of loss across the

image, avoiding large variations.

4.5 Adaptive predictor

To improve compression ratio, legacy JPEG subtracts the value of the DC coefficient for the previously encoded

block from the DC coefficient of the current block. Because of local similarities displayed by typical images, this

results in significant savings.

However, this prediction mode is fairly primitive, and does not take into account the bidimensional nature of

images. To address this concern, JPEG XL uses a bidimensional “adaptive” predictor, that chooses between eight

different prediction modes, based on their behaviour on nearby pixels. This predictor is used for DC encoding,

but also for the encoding of various control fields.

More specifically, when predicting a value in position (x, y), the adaptive predictor looks at the maximum

error that each prediction mode would have produced on pixels (x − 1, y), (x, y − 1) and (x − 1, y − 1), and chooses

the prediction mode that is expected to produce the least amount of error. If the expected error computed this

way is 0, the adaptive predictor also keeps track of the number of prediction modes that are expected to reach

this accuracy level. The expected error and the number of “correct” prediction modes is used to split the encoded

residuals into multiple distributions. This allows significant size savings, since this procedure detects flat areas

in the image and uses specific distributions for them.

A variation of this predictor is used for lossless mode. The lossless predictor uses fewer prediction modes

(four instead of eight), but computes a weighted average of the predictions instead of choosing one of them.

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137 111370K-9

Figure 6. Example of banding on low quality images: left original, right compressed image.

4.6 DC handling

One of the most noticeable artefacts produced by JPEG compression at lower quality is banding, the transforma-

tion of an area of the image containing a slowly varying color (such as the sky at sunset) into one that contains

a few bands of the same color (see Figure 6). This creates very noticeable artefacts at the boundaries between

two different bands.

Banding in JPEG is typically caused by DC quantization. To avoid this effect, JPEG XL allows using finer

quantization steps for encoding residuals that are close to 0 in the original image. This is in practice equivalent

to using finer quantization steps in areas that are slowly varying, but without sacrificing compression ratio as

much as using finer quantization on the whole image would do.

To further reduce banding in areas with steeper gradients, JPEG XL applies a selective smoothing algorithm

to the DC image, that is only allowed to move values inside their quantization boundaries. If the smoothed value

would be outside of the quantization boundaries, it is discarded, and the original is used.

4.7 LF predictions

To reduce banding further, and to make block artefacts less noticeable in the resulting image, JPEG XL estimates

the low-frequency coefficients of each X × Y transform (the top-left corner of size X Y X Y

4 × 4 , excluding the 8 × 8

X Y X Y

corner) from the DC image. This procedure starts by extending the known 8 × 8 coefficients to have size 4 × 4 ,

by filling missing coefficients with zeros. It then uses the inverse of the first procedure described in Lemma 4.1

on each block to produce a 2× upsampled version of the DC image.

After applying the a smoothing algorithm similar to the one used on the DC image, the upsampled DC is

converted back to DCT coefficients; the low-frequency values that are produced this way are then added to the

encoded low-frequency coefficients.

4.8 AC encoding

JPEG always encodes AC coefficients using the so-called zig-zag order, which proceeds in order of increasing

sum of coordinates in the block.

As JPEG XL uses different transform sizes, it generalizes the zig-zag order to those cases. Moreover, since

this order is not necessarily optimal for a given image, it allows to encode a custom order. This custom order

is encoded as a permutation of the zig-zag order, using a Lehmer15 -like code to achieve efficient encoding of the

identity permutation.

The encoding of AC coefficients proceeds in the order specified above; it keeps track of the number of remaining

non-zeros in the current block, using that value, combined with the current position, to split coefficients into

multiple distributions. No further values are present in the bitstream when it is known that no non-zero coefficient

is left.

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137 111370K-10

Figure 7. Example of ringing on low quality images: left original, right compressed image. Because of ringing, the sky is

not flat in the regions close to the tree branches.

4.9 Loop filters

Despite the significant improvements that JPEG XL delivers to reduce artefacts, block boundaries and ringing

can still be noticed, especially at somewhat lower qualities. Ringing artefacts are spurious signals near sharp

edges, caused by quantizing or truncating high-frequency components (see Figure 7). To mitigate their impact,

JPEG XL employs two different loop filters that are applied to the image after the decompression process.

The first loop filter is a smoothing convolution. As smoothing the image inherently introduces a sharpness

loss, this effect is compensated by the encoder by means of a sharpening filter that is applied before the DCT

step. The overall effect of this procedure is that the visual impact of block boundaries gets reduced, while still

preserving sharp details present in the original image.

The second loop filter is intended to reduce ringing, while still preserving texture that is transmitted in the

image. To achieve this effect, it applies an adaptive smoothing algorithm related to Non-Local Means,16 with

some modifications to improve processing speed. To further improve the detail preservation of this filter, the

JPEG XL format can require the decoder to apply a quantization constraint to the output of the filter: the DCT

step is applied again, and the decoder ensures that the resulting coefficients are inside the range of values that

would have been quantized to the coefficient read from the bitstream by clamping. The decoder then applies an

IDCT step again to produce the final output of the filter.

4.10 Image features

Certain image features can pose challenges to the DCT and are sometimes best handled by dedicated tools. This

section presents a few such encoding tools that are specified by JPEG XL.

One such technique that JPEG XL allows is to draw splines on top of the decoded image by means of addition

in XYB space. More specifically, they consist in an approximation of centripetal Catmull-Rom splines, along

which evenly-spaced (1 pixel apart) strokes of a Gaussian brush are applied. The color of the brush and the

variance of the Gaussian kernel can vary along the spline and are each encoded using the DCT32 transform.

Another technique concerns dots, by which we mean one or very few pixels that are visibly very different

from their neighboring pixels. At lower quality, due to the nature of DCT transforms used by JPEG XL, the

disappearance of dots might be a noticeable artefact. To mitigate this effect, JPEG XL allows to draw dots that

get summed to the decoded images. Those dots are modeled as bidimensional Gaussians, which may have an

elliptical shape, with various rotations of the axes and intensities.

JPEG XL allows to add patches to an image. Patches are small pixel patterns. When those patches appear

multiple times in an image, it might be beneficial to store them only once, together with the positions where

they appear. This can be used for example to improve the appearance of compressed printed text in an image,

which is also problematic to represent in a DCT-based codec.

There is tendency that noise, when present in the original image, is lost when compressed. To recover more

realistic looking images, JPEG XL allows to add noise to the image. We employ an intensity dependent noise

model.17 A pseudorandom procedure generates the noise that is added to the image.

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137 111370K-11

4.11 Group splitting

If the image to be encoded is large enough (more than 256 pixels along any axis), it is split into sub-rectangles of

size at most 256 × 256, which are encoded independently. The bitstream also contains an index of the bitstream

positions of those rectangles that allows decoders to seek to the start of each.

This gives four benefits: it allows decoders to process each rectangle independently in parallel, to decode only

selected regions of large images, to rearrange rectangles (e.g. in saliency order) and to restart decoding if a prior

rectangle is corrupted.

4.12 DCT-based progressive image

The JPEG XL bitstream can contain AC coefficients in multiple passes that are summed together. This allows to

progressively encode images, by sending low-frequency coefficients first, and higher frequency coefficients later.

It is also possible to refine quality in selected regions of the image in a given pass, allowing area-of-interest

progressive decoding.

DC coefficients are always sent first, so it is always possible to obtain an 8× downsampled image from the

JPEG XL bitstream without reading the full file.

4.13 JPEG recompression

JPEG recompression allows smooth migration from legacy JPEG to JPEG XL: existing JPEG files can be

losslessly transformed to the newer and more compact format.

The legacy JPEG format has been thoroughly explored18, 19 over the years and most of its inefficiencies are

addressed in the JPEG XL recompression format:

• more robust DC coefficient prediction is used

• AC0x and ACx0 coefficients are predicted on the base of neighboring blocks

• Huffman entropy encoding is replaced with ANS and Binary Arithmetic coding

• frequently used ICC profiles, Huffman code tables, and quantization tables are encoded as template pa-

rameters

• context modeling is used to separate entropy sources

• similar to the approach described in Section 4.8, DCT coefficients are reordered in a such way that more

blocks have longer series of zeros at the end. The index of last non-zero coefficient is encoded explicitly,

which is more efficient than limited RLE.

Those improvements enable 16% size savings on average in a corpus of 100 000 random images from the

Internet. For larger photographic images, the savings are in the range 13%–22%, depending on the JPEG

encoder and quality settings.

5. CONCLUSIONS

This paper introduces the coding tools used in JPEG XL: a new approach for responsive images, and a variable-

size DCT designed from the ground up for economical storage of high-quality images.

Large-scale user metrics indicate that most use cases on the internet target higher quality levels than previ-

ously assumed in codec design. This helps explain why codecs optimized for lower bitrates have not supplanted

the 27-year-old JPEG standard. We present new quality-of-experience data indicating JPEG XL requires less

than half the bitrate of JPEG to achieve perceptually lossless storage, with fewer outliers. In other experiments,

we have found JPEG XL encodings to be 33–40% of the size of libjpeg output at similar psychovisual quality.

We acknowledge that JPEG and JPEG XL will co-exist. Rather than reduce the quality of existing images

by transcoding, or increase hosting costs by storing both formats, we propose to build a bridge between JPEG

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137 111370K-12

and JPEG XL. The coding tools are carefully designed to interoperate with JPEG, allowing us to shrink existing

images without quality loss and create new images that can be transcoded back to JPEG. This creates a gradual

update path which benefits both hosts and users at each step.

We believe this fresh approach will overcome previous difficulties in replacing the highly successful JPEG,

GIF, and PNG formats, and help establish a modern format that simplifies image serving, improves quality and

reduces user-experienced latency.

REFERENCES

[1] Wallace, G. K., “The JPEG still picture compression standard,” IEEE transactions on consumer electron-

ics 38(1), xviii–xxxiv (1992).

[2] “Final call for proposals for a next-generation image coding standard (JPEG XL).” https://jpeg.org/

downloads/jpegxl/jpegxl-cfp.pdf. Accessed 2019-07-26.

[3] “Github - google/pik: A new lossy/lossless image format for photos and the internet.” https://github.

com/google/pik. Accessed 2019-07-26.

[4] “Github - cloudinary/fuif: Free universal image format.” https://github.com/cloudinary/fuif. Accessed

2019-07-26.

[5] “Worldwide broadband speed league 2019.” https://www.cable.co.uk/broadband/speed/

worldwide-speed-league/. Accessed: 2019-07-25.

[6] “Image compression benchmark.” http://imagecompression.info/. Accessed: 2019-07-25.

[7] Alakuijala, J., “Image compression benchmark.” https://drive.google.com/corp/drive/folders/0B0w_

eoSgaBLXY1JlYUVOMzM5VFk. Accessed: 2019-07-25.

[8] “libjpeg 1.5.2 release.” https://github.com/libjpeg-turbo/libjpeg-turbo/releases/tag/1.5.2. Re-

leased 2017-08-09.

[9] Rhatushnyak, A., Wassenberg, J., Sneyers, J., Alakuijala, J., Vandevenne, L., Versari, L., Obryk, R.,

Szabadka, Z., Kliuchnikov, E., Comsa, I.-M., Potempa, K., Bruse, M., Firsching, M., Khasanova, R., van

Asseldonk, R., Boukortt, S., Gomez, S., and Fischbacher, T., “Committee draft of JPEG XL image coding

system,” (2019).

[10] Arai, Y., Agui, T., and Nakajima, M., “A fast DCT-SQ scheme for images,” IEICE TRANSACTIONS

(1976-1990) 71(11), 1095–1097 (1988).

[11] Vashkevich, M. and Petrovsky, A., “A low multiplicative complexity fast recursive DCT-2 algorithm,” arXiv

preprint arXiv:1203.3442 (2012).

[12] Huffman, D. A., “A method for the construction of minimum-redundancy codes,” Proceedings of the

IRE 40(9), 1098–1101 (1952).

[13] Rissanen, J. and Langdon, G. G., “Arithmetic coding,” IBM Journal of research and development 23(2),

149–162 (1979).

[14] Duda, J., Tahboub, K., Gadgil, N. J., and Delp, E. J., “The use of asymmetric numeral systems as an

accurate replacement for Huffman coding,” in [2015 Picture Coding Symposium (PCS)], 65–69, IEEE (2015).

[15] Laisant, C.-A., “Sur la numération factorielle, application aux permutations,” Bulletin de la Société

Mathématique de France 16, 176–183 (1888).

[16] Buades, A., Coll, B., and Morel, J.-M., “A non-local algorithm for image denoising,” in [2005 IEEE Com-

puter Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR’05)], 2, 60–65, IEEE (2005).

[17] Khasanova, R., Wassenberg, J., and Alakuijala, J., “Noise generation for compression algorithms,”

CoRR abs/1803.09165 (2018).

[18] Lakhani, G., “DCT coefficient prediction for JPEG image coding,” in [2007 IEEE International Conference

on Image Processing], 4, IV – 189–IV – 192 (Sep. 2007).

[19] Richter, T., “JPEG on STEROIDS: Common optimization techniques for JPEG image compression,” in

[2016 IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP)], 61–65 (Sep. 2016).

Proc. of SPIE Vol. 11137 111370K-13

You might also like

- 01 Operating Manual CheckweigherDocument114 pages01 Operating Manual CheckweigherSOHAIL WAHAB0% (1)

- Jpeg Image Compression Using DCTDocument56 pagesJpeg Image Compression Using DCTRaghavendra Kulal100% (2)

- Jurisdiction in Cyber SpaceDocument23 pagesJurisdiction in Cyber SpaceNancy RohillaNo ratings yet

- Decompression of JPEG Document Images: A Survey Paper: Miss. Punam N. Kamble Mr.C. J. AwatiDocument3 pagesDecompression of JPEG Document Images: A Survey Paper: Miss. Punam N. Kamble Mr.C. J. AwatiEditor IJRITCCNo ratings yet

- Wallace - JPEG - 1992Document17 pagesWallace - JPEG - 1992floriniiiNo ratings yet

- An Algorithm For Image Compression Using 2D Wavelet TransformDocument5 pagesAn Algorithm For Image Compression Using 2D Wavelet TransformIJMERNo ratings yet

- Image Compression System Using H.264 EncodingDocument6 pagesImage Compression System Using H.264 EncodingIJSTENo ratings yet

- Thesis On Image Compression PDFDocument5 pagesThesis On Image Compression PDFlorigilbertgilbert100% (2)

- Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation Volume 59 Issue 2019 (Doi 10.1016 - J.jvcir.2018.12.043) Yuan, Shuyun Hu, Jianbo - Research On Image Compression Technology Based On HuffmanDocument6 pagesJournal of Visual Communication and Image Representation Volume 59 Issue 2019 (Doi 10.1016 - J.jvcir.2018.12.043) Yuan, Shuyun Hu, Jianbo - Research On Image Compression Technology Based On HuffmanpusherNo ratings yet

- New Trends in Image and Video CompressionDocument7 pagesNew Trends in Image and Video CompressionSrinivasan JeganNo ratings yet

- Novel Technique For Improving The Metrics of Jpeg Compression SystemDocument8 pagesNovel Technique For Improving The Metrics of Jpeg Compression SystemInternational Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementNo ratings yet

- SCAN Chain Based Clock Gating For Low Power Video Codec DesignDocument7 pagesSCAN Chain Based Clock Gating For Low Power Video Codec DesignSaravanan NsNo ratings yet

- Jpeg Compression Metric As Aquality Aware Image TranscodingDocument13 pagesJpeg Compression Metric As Aquality Aware Image TranscodingcthjgfytvfnoNo ratings yet

- Lossless Recompression of JPEG Images Using Transform Domain Intra PredictionDocument12 pagesLossless Recompression of JPEG Images Using Transform Domain Intra Predictionbvkarthik2711No ratings yet

- Anjay PDFDocument17 pagesAnjay PDFAndro Elnatan HarianjaNo ratings yet

- Makalah - TA Thazin AungsoeDocument6 pagesMakalah - TA Thazin AungsoesenopatirawuhNo ratings yet

- Image Compression: by Artificial Neural NetworksDocument14 pagesImage Compression: by Artificial Neural NetworksvasuvlsiNo ratings yet

- Jpeg OptDocument141 pagesJpeg OptjatputtarNo ratings yet

- JpegDocument2 pagesJpegCoz AnimationNo ratings yet

- Design of JPEG Compression StandardDocument2 pagesDesign of JPEG Compression StandardSarah SolisNo ratings yet

- Patch-Based Image Learned Codec Using OverlappingDocument21 pagesPatch-Based Image Learned Codec Using OverlappingsipijNo ratings yet

- International Journal of Engineering Research and Development (IJERD)Document7 pagesInternational Journal of Engineering Research and Development (IJERD)IJERDNo ratings yet

- An Analysis in Various Compression AlgorithmsDocument5 pagesAn Analysis in Various Compression Algorithmssurendiran123No ratings yet

- Digital Image Forensic Approach To Counter The JPEG Anti-Forensic AttacksDocument12 pagesDigital Image Forensic Approach To Counter The JPEG Anti-Forensic Attacksasriza yolandaNo ratings yet

- Wavelet-Based Image Compression: By: Heriniaina Andrianirina #1817662 Akakpo Agbago #1817699Document19 pagesWavelet-Based Image Compression: By: Heriniaina Andrianirina #1817662 Akakpo Agbago #1817699Raja DineshNo ratings yet

- Compression TechniquesDocument7 pagesCompression TechniquesMatthew ElokunNo ratings yet

- Deep Learning-Based Video Coding - A Review and A Case StudyDocument35 pagesDeep Learning-Based Video Coding - A Review and A Case Studyqi848475885No ratings yet

- Data Communication: Assignment No: 2bDocument14 pagesData Communication: Assignment No: 2bManjesh KumarNo ratings yet

- Delivery of High Quality Uncompressed Video Over ATM To Windows NT DesktopDocument14 pagesDelivery of High Quality Uncompressed Video Over ATM To Windows NT DesktopAdy AndyyNo ratings yet

- Image CompressionDocument26 pagesImage Compressiond56468901No ratings yet

- My ProjectDocument89 pagesMy ProjectumamaheshbattaNo ratings yet

- Subjective Image Quality Tradeoff Between Spatial Resolution and Quantization NoiseDocument23 pagesSubjective Image Quality Tradeoff Between Spatial Resolution and Quantization NoiseHcv Prasad KacharlaNo ratings yet

- Computer Networks Introduction Computer NetworkingDocument21 pagesComputer Networks Introduction Computer Networkingsuraj18in4u100% (1)

- BayersDocument4 pagesBayersprojectinbangalore279No ratings yet

- Error Detection and Data Recovery Architecture For Motion EstimationDocument63 pagesError Detection and Data Recovery Architecture For Motion Estimationkasaragadda100% (1)

- Digital Video Concepts Methods and Metrics Quality Compression Performance and Power Trade Off Analysis 1st Edition Shahriar Akramullah (Auth.)Document84 pagesDigital Video Concepts Methods and Metrics Quality Compression Performance and Power Trade Off Analysis 1st Edition Shahriar Akramullah (Auth.)zhanareege100% (2)

- The Jpeg2000 Still Image Coding System: An Overview: Senior Member, IEEE Senior Member, IEEE Member, IEEEDocument25 pagesThe Jpeg2000 Still Image Coding System: An Overview: Senior Member, IEEE Senior Member, IEEE Member, IEEEVignesh sankar uNo ratings yet

- Image Compression Using Huffman CodingDocument25 pagesImage Compression Using Huffman CodingAayush GuptaNo ratings yet

- Literature Review On Different Compression TechniquesDocument5 pagesLiterature Review On Different Compression TechniquesInternational Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementNo ratings yet

- Joint Photographic Experts Group: Unlocking the Power of Visual Data with the JPEG StandardFrom EverandJoint Photographic Experts Group: Unlocking the Power of Visual Data with the JPEG StandardNo ratings yet

- T E V V: A S S T C A: HE Volution of Olumetric Ideo Urvey of Mart Ranscoding and Ompression PproachesDocument11 pagesT E V V: A S S T C A: HE Volution of Olumetric Ideo Urvey of Mart Ranscoding and Ompression Pproachesgeek.bill.0No ratings yet

- Applying and Extending ISOTC42 Digital Camera ResoDocument10 pagesApplying and Extending ISOTC42 Digital Camera ResoChiNo ratings yet

- 5615 Ijcsa 06Document11 pages5615 Ijcsa 06Anonymous lVQ83F8mCNo ratings yet

- Haar Wavelet Based Approach For Image Compression and Quality Assessment of Compressed ImageDocument8 pagesHaar Wavelet Based Approach For Image Compression and Quality Assessment of Compressed ImageLavanya NallamNo ratings yet

- Jpeg Image Compression Using FpgaDocument2 pagesJpeg Image Compression Using FpgaInternational Journal of Application or Innovation in Engineering & ManagementNo ratings yet

- MPEG-2 Long GoP Vs AVC Comp-StrategiesDocument22 pagesMPEG-2 Long GoP Vs AVC Comp-Strategiessathis_nskNo ratings yet

- JPEG Image Compression and Decompression by Huffman CodingDocument7 pagesJPEG Image Compression and Decompression by Huffman CodingInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Video Saliency Detection Using Modified High Efficiency Video Coding and Background ModellingDocument10 pagesVideo Saliency Detection Using Modified High Efficiency Video Coding and Background ModellingIJRES teamNo ratings yet

- MpegDocument2 pagesMpegumar khanNo ratings yet

- Design and Implementation of An Optimized Video Compression Technique Used in Surveillance System For Person Detection With Night Image EstimationDocument13 pagesDesign and Implementation of An Optimized Video Compression Technique Used in Surveillance System For Person Detection With Night Image EstimationChetan GowdaNo ratings yet

- Lossless Video Compression For Archives: Motion JPEG2k and Other OptionsDocument8 pagesLossless Video Compression For Archives: Motion JPEG2k and Other Optionsmbush6000No ratings yet

- Video Database: Role of Video Feature ExtractionDocument5 pagesVideo Database: Role of Video Feature Extractionmulayam singh yadavNo ratings yet

- Discovering Robustness Amongst CBIR FeaturesDocument13 pagesDiscovering Robustness Amongst CBIR FeaturesijwestNo ratings yet

- Fractal Image Compression-A ReviewDocument4 pagesFractal Image Compression-A Revieweditor_ijarcsseNo ratings yet

- FPGA Based Implementation of Baseline JPEG DecoderDocument7 pagesFPGA Based Implementation of Baseline JPEG DecoderUmar AnjumNo ratings yet

- Efficient Algorithm For Digital Image SteganographyDocument6 pagesEfficient Algorithm For Digital Image SteganographySuraj VernekarNo ratings yet

- Compression of Hyperspectral Image Using JPEG Compression AlgorithmDocument9 pagesCompression of Hyperspectral Image Using JPEG Compression AlgorithmInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Oblivious Image Watermarking Combined With JPEG CompressionDocument9 pagesOblivious Image Watermarking Combined With JPEG Compressionray11145No ratings yet

- Jpeg Image Compression ThesisDocument6 pagesJpeg Image Compression Thesisgjga9bey100% (1)

- Image Compression Using VerilogDocument5 pagesImage Compression Using VerilogvisuNo ratings yet

- Image, Video Compression Techniques: JPEG, MPEG: Seminar Report OnDocument55 pagesImage, Video Compression Techniques: JPEG, MPEG: Seminar Report Onpriyanka07422No ratings yet

- Image Compression: Efficient Techniques for Visual Data OptimizationFrom EverandImage Compression: Efficient Techniques for Visual Data OptimizationNo ratings yet

- LM 7131Document28 pagesLM 7131NathanNo ratings yet

- CS201 MIDTERM SOLVED MCQS by JUNAIDDocument47 pagesCS201 MIDTERM SOLVED MCQS by JUNAIDAzhar Dogar100% (3)

- Baggage Handling: by Sharmin Naz 1 Year Mba in Aviation ManagementDocument19 pagesBaggage Handling: by Sharmin Naz 1 Year Mba in Aviation ManagementSharminNo ratings yet

- EZVIZ Camera - Guide Démarrage RapideDocument34 pagesEZVIZ Camera - Guide Démarrage Rapiderom1486No ratings yet

- MSSIAH WavePlayerDocument21 pagesMSSIAH WavePlayerReno Wrestlehoff2No ratings yet

- DX DiagDocument42 pagesDX DiagCao Cường ĐỗNo ratings yet

- Ai Unit2 RejinpaulDocument81 pagesAi Unit2 RejinpaulJohnwilliam PNo ratings yet

- 2020 Cohort Handout On Chapter 17.2-17.3 - Further Differentiation - Teacher'sDocument18 pages2020 Cohort Handout On Chapter 17.2-17.3 - Further Differentiation - Teacher'sSharia NehaNo ratings yet

- Have Get Something Done British English Student PDFDocument3 pagesHave Get Something Done British English Student PDFAlejandro GarcíaNo ratings yet

- Multimedia System - Quiz 2Document22 pagesMultimedia System - Quiz 2Alesa DaffonNo ratings yet

- Your Electronic Ticket Receipt (1) GarudaDocument2 pagesYour Electronic Ticket Receipt (1) GarudaindahNo ratings yet

- Asc Installation Instructions 4189341076 UkDocument29 pagesAsc Installation Instructions 4189341076 UkEmmanuel ValiaoNo ratings yet

- A Landscape Orientation Resume TemplateDocument1 pageA Landscape Orientation Resume TemplatePadmanabha HollaNo ratings yet

- Installation: Base Transceiver Station Equipment Imn:Btse Bs40Document62 pagesInstallation: Base Transceiver Station Equipment Imn:Btse Bs40AlexandarNo ratings yet

- Labour Relations Practice QuizDocument8 pagesLabour Relations Practice QuizGavin WallNo ratings yet

- User Manual: WWW - Tcl.euDocument20 pagesUser Manual: WWW - Tcl.euFilipe ConceiçãoNo ratings yet

- Lesson 7 GEE 5 IT EraDocument3 pagesLesson 7 GEE 5 IT Erastephaniejeancortez522No ratings yet

- Geospatial Analytics For IoTDocument4 pagesGeospatial Analytics For IoTDyutish BandyopadhyayNo ratings yet

- "Atm Management System": VENKATESHA GS. (2GO19CS038) NAWAZ ALI. (2GO19CS046)Document9 pages"Atm Management System": VENKATESHA GS. (2GO19CS038) NAWAZ ALI. (2GO19CS046)Barath KtNo ratings yet

- State Wise Aadhaar SaturationDocument3 pagesState Wise Aadhaar SaturationRaghavendranNo ratings yet

- Sudheer ResumeDocument3 pagesSudheer Resumesudheer munagalaNo ratings yet

- Artificial IntelligenceDocument16 pagesArtificial Intelligencenegari1174No ratings yet

- Curriculum of Certificate Course in Medical Transcription: Syllabus andDocument8 pagesCurriculum of Certificate Course in Medical Transcription: Syllabus andJustin JaspherNo ratings yet

- WC LAB Manual FinalDocument73 pagesWC LAB Manual FinalhtasarpnuraNo ratings yet

- инструкция Yamaha BRX-750Document169 pagesинструкция Yamaha BRX-750евгенийNo ratings yet

- Cs3451-Ios Revision 2 Q&aDocument7 pagesCs3451-Ios Revision 2 Q&ajeevankumar2708No ratings yet

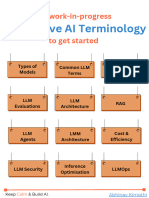

- Generative Ai TerminologyDocument26 pagesGenerative Ai TerminologyDiksha AggrawalNo ratings yet

- Book Report - 1177 - AIDocument9 pagesBook Report - 1177 - AIsairamteja nekkantiNo ratings yet