Intersectionality

Intersectionality

Uploaded by

Aklilu EndalamawCopyright:

Available Formats

Intersectionality

Intersectionality

Uploaded by

Aklilu EndalamawCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Intersectionality

Intersectionality

Uploaded by

Aklilu EndalamawCopyright:

Available Formats

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH

RESEARCH ARTICLE

Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude,

and testing related to HIV in Ethiopia: People

with multiple disadvantages are left behind

Aklilu Endalamaw ID1,2*, Charles F. Gilks ID1, Resham B. Khatri1, Yibeltal Assefa1

1 School of Public Health, The University of Queensland, Brisbane, Australia, 2 College of Medicine and

Health Sciences, Bahir Dar University, Bahir Dar, Ethiopia

* yaklilu12@gmail.com

a1111111111

a1111111111

a1111111111

a1111111111 Abstract

a1111111111

Intersectionality pinpoints intersecting factors that empower or oppress people with multiple

(dis)advantageous conditions. This study examined intersectional inequity in knowledge, atti-

tudes, and testing related to HIV among adults aged 15 to 49 years in Ethiopia. This study

used nationally representative 2016 Ethiopian Demographic Health Survey data. The sample

OPEN ACCESS

size was 27,261 for knowledge about HIV/AIDS and 25,542 for attitude towards people living

Citation: Endalamaw A, Gilks CF, Khatri RB, Assefa

with HIV and HIV testing. Triple (dis)advantage groups were based on wealth status, educa-

Y (2024) Intersectional inequity in knowledge,

attitude, and testing related to HIV in Ethiopia: tion status, and residence. The triple advantages variables specifically are urban residents,

People with multiple disadvantages are left behind. the educated, and those who belong to households of high wealth status, while the triple dis-

PLOS Glob Public Health 4(8): e0003628. https:// advantages are rural residents, the uneducated, and those who live in poor household wealth

doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628

rank. A multilevel logistic regression analysis was employed. Adjusted odds ratios (aOR) and

Editor: Julia Robinson, PLOS: Public Library of confidence intervals (CI) with a P-value � 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Science, UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

Based on descriptive analysis, 27.9% (95% CI: 26.5%, 29.3%) of adults had comprehensive

Received: April 15, 2024 knowledge about HIV/AIDS, 39.8% (95% CI: 37.6, 41.9%) exhibited accepting attitude

Accepted: July 30, 2024 towards people living with HIV, and 20.4% (95% CI: 19.1%, 21.8%) undergo HIV testing.

Published: August 22, 2024 Comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS, accepting attitude towards people living with

HIV, and HIV testing was 47.0%, 75.7%, and 36.1% among those with triple advantages,

Peer Review History: PLOS recognizes the

benefits of transparency in the peer review and 13.9%, 16.0% and 8.7% among those with triple non-advantages, respectively. The

process; therefore, we enable the publication of odds of having comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS, accepting attitude towards peo-

all of the content of peer review and author ple living with HIV, and HIV testing were about three (aOR = 3.4; 95% CI: 2.76 to 4.21),

responses alongside final, published articles. The

seven (aOR = 7.3; 95% CI = 5.79 to 9.24) and five (aOR = 4.7; 95% CI:3.60 to 6.10) times

editorial history of this article is available here:

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 higher for triple forms of advantage than triple disadvantages, respectively. The findings of

this study imply that Ethiopia will not achieve the proposed targets for HIV/AIDS services

Copyright: © 2024 Endalamaw et al. This is an

open access article distributed under the terms of unless it prioritises individuals who live under multiple disadvantaged conditions.

the Creative Commons Attribution License, which

permits unrestricted use, distribution, and

reproduction in any medium, provided the original

author and source are credited.

Data Availability Statement: All data underlying Introduction

the findings are provided in the submitted

manuscript. The Ethiopian demographic health Equity analysis using an intersectional lens plays a significant role in the understanding of

survey data that we obtained from DHS was complex and chronic health issues. For example, HIV/AIDS is a pandemic of intersectional

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 1 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

acquired through an official request made to DHS. inequity, fuelled by gender, income, and education status inequities at the individual, commu-

To access the DHS Program, please visit their nity, and programme levels [1]. Hence, HIV/AIDS prevention and control programmes

website at https://dhsprogram.com/.

require a complex start-up with an understanding of intersectionality in providing behavioural

Funding: The authors received no specific funding services to promote knowledge and attitude, as well as HIV testing [2]. HIV testing is one of

for this work. the global fast-track goals aimed at reaching 95% of people living with HIV expected to be

Competing interests: The authors have declared tested by 2025, which requires contemplating several obstacles [3]. For example, Ethiopia

that no competing interests exist. plans that 90% of key and priority populations will have comprehensive knowledge about

HIV/AIDS and an accepting attitude towards people living with HIV, as well as knowing their

HIV status by 2025 [4]. Ethiopia is among the top fifteen African countries based on the num-

ber of people living with HIV (0.62 million) [5], demanding continuous evidence of the com-

prehensive HIV prevention services.

There have been studies on the overall status and associated factors of knowledge about

HIV/AIDS among different population groups in Ethiopia. For instance, a study conducted in

2020 found that 51.4% of university students had knowledge about HIV/AIDS, and this was

positively associated with a better education status and a higher income level [6]. Additionally,

another study revealed that 72% of adolescent students had a positive attitude towards HIV/

AIDS [7]. Attitudes towards people living with HIV manifest as stigma and discrimination.

Previous studies investigated stigma and discrimination using similar questions related to atti-

tudes towards people living with HIV [8, 9]. This issue remains a continuous concern in imple-

menting prevention and control strategies for HIV/AIDS [10]. Similarly, a meta-analysis

finding based on published article from 2010 to 2019 revealed that the HIV status coverage

was about 78% among pregnant women in Ethiopia, as it was much higher among urban resi-

dents [11]. These and other available studies have emphasised only one dimension of social

categories, such as residence or education status [6, 7, 12–15], while researchers argue the

importance of investigating intersectional inequity. Researchers and stakeholders accept the

importance of the intersectional approach [16]. The challenge was the lack of evidence on

intersectionality in low-income countries, including Ethiopia [17]. This implies that studies on

intersectional inequity may contribute to equitable HIV/AIDS services provision.

Intersectionality is a public health concept that plays a critical role in service provision and

utilisation as well as disease prevention and control [18]. It is the sharing of characters in over-

lapping or interdependent social identities, social strata or divisions considered non-medical

factors of health [19], such as race, gender, economic power, and class [20]. It can also be seen

as an analytical framework for exploring inequity that evolves from intersecting disadvantages

[21], arguing that an individual with combined disadvantaged character has a lower probabil-

ity of accessing services than the single disadvantaged character. Crenshaw described intersec-

tionality as inequities due to individuals being in disadvantageous classes; for instance, black

in race and women in sexual orientation [22]. Hurtado also argued how the multiple sources

of inequity result in intersectional identities and unveiled an examination of intersectionality

inequity [23].

Intersectionality challenges progress towards national and global health targets. Inequity

arises from underprivileged social classes in dynamic cultural, economic, political, and health

care contexts [24]. For example, people in low socioeconomic conditions experienced lower

access to health services, revealing the presence of inequity in healthcare [25]. This inequity is

also discernible among individuals with multiple disadvantages [26], again linked to intersec-

tionality theory, involving social and community position, and programme practice [27–29].

Overall, the interaction of social identities is apparent in health services, including HIV/AIDS

services [30–32], which needs to be addressed for equality and inclusiveness [33–36] and

implies the need for assessing the extent of inequities at the intersection despite known indi-

vidual determinants [34].

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 2 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

As a result, there has been increasing global attention to intersectionality in research, poli-

cies, and programmes. The recent global health target under the Sustainable Development

Goals highlights the provision of health services to all people who need them, irrespective of

individual backgrounds [37]. The Joint United Nations Programme for HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS)

advised assessing intersecting inequities towards ending AIDS epidemics [38]. This under-

scores the programmatic and policy relevance of investigating intersectionality and inequity in

health services [30, 36, 39, 40].

Therefore, we argue individuals with multiple disadvantages will have lower knowledge

about HIV/AIDS, an unfavourable attitude towards people living with HIV, and a lower

chance of being tested for HIV. The findings will have clinical, programme and policy implica-

tions. This study investigated intersectional inequity in knowledge about HIV/AIDS, attitudes

towards people living with HIV, and HIV testing in Ethiopia.

Methods

Study design and setting

A population-based cross-sectional study design was conducted in Ethiopia (S1 Checklist).

Ethiopia is in eastern Africa. Ethiopia is Africa’s second-most populated country with a popu-

lation of nearly 126 million [41], ranked 153rd out of 167 countries in the overall Prosperity

Index [42], and ranked 97 out of 156 countries based on the gender gap index score [43].

Around 21.3% population lives in urban areas [44]. This country is geographically divided into

ten regions and two cities. These are Tigray, Amhara, Afar, Benshanigul Gumuz, Gambela,

Harar, Somali, Oromia, Southern Nations Nationalities and People Region (SNNPR), Sidama,

and two cities: Dire Dawa and Addis Ababa. Sidama is a new region that was in SNNPR before

2020. The last Ethiopian-based population-based survey with HIV/AIDS-related indicators

was conducted in 2016, in which nine geographic regions were included. The country’s HIV/

AIDS-related strategic plans and clinical mentoring guidelines are based on the 2016 popula-

tion-based survey [45].

Conceptual framework

Using the research questions with a focus on dependent and independent variables, the con-

ceptual framework for the current study was adapted from the social determinants of health

concepts. The WHO has developed the conceptual framework for social determinants of

health using socioeconomic and political context (governance, microeconomic, public and

social policies, cultural and societal values) and socioeconomic position (gender, ethnicity,

education, occupation, income) as structural determinants, and material circumstances (living

conditions), behavioural and biological factors, and psychosocial factors as intermediary social

determinants of health equity and wellbeing as the outcome [46]. Commission of the Pan

American Health Organisation has included intersectionality as a social determinant of health

equity [47].

The current study has three outcome variables related to inequities: knowledge about HIV/

AIDS, an accepting attitude towards people living with HIV, and recent HIV tests across

explanatory variables, which are social determinants of health. Fig 1 displays the social deter-

minants adapted from the social determinants of health framework (Fig 1).

Variables

Outcome variables. Comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS, attitude towards peo-

ple living with HIV, and HIV testing are the outcome variables based on Demographic Health

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 3 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

Fig 1. Conceptual framework adapted based on the social determinants of health framework.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628.g001

Survey (DHS) definition [48, 49]. A series of questions were used to generate the level of

knowledge. All adults who had ever heard of HIV/AIDS responded to five questions. These are

knowing about the two most common methods to prevent HIV/AIDS infection (‘consistent

condom use’ and ‘limiting the number of sexual partners to one HIV uninfected faithful part-

ner’), answering correctly to ‘a healthy-looking person can have HIV/AIDS’ and rejecting the

two misconceptions about HIV/AIDS, which are ‘a person can get HIV from a mosquito bite’,

and ‘a person can get HIV by sharing a meal with people living with HIV’. Regarding attitude

towards people living with HIV, respondents who have heard of HIV/AIDS were asked two

consecutive questions: 1) ‘would you buy fresh vegetables from a shopkeeper/vendor who had

HIV/AIDS?’ and 2) ‘should children with HIV not be allowed to attend school with children

without HIV?’ Those who answered two attitude questions positively were considered to have

accepting attitude, while those who responded negatively to either of the questions were

recorded as having no accepting attitude. The third outcome variable (recent HIV testing and

received test result) is whether respondents tested for HIV within 12 months preceding the

survey and received test results, represented by HIV testing status in the current manuscript.

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 4 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

Independent variables. The current study examined the intersection of education status,

household wealth status, and residence as well as employment status and gender towards HIV/

AIDS related knowledge, attitude, and testing. This study classified residence, socioeconomic

status, and education status as triple intersections while gender and employment status were

selected as intersection variables. Of the many distinctions in the social determinants of health,

gender and employment status have been historically integrated; women are usually house-

wives and men are employed [50]. Similarly, residence, education, and economic status are

interacting social determinants. These intersecting variables result in health service uptake or

coverage disparity between individuals [51]. Hence, looking for the difference between advan-

taged and disadvantaged groups based on the junction of gender and employment status, and

residence area, education, and income status could share several factors. The clustering effect

of these intersectional determinants was examined in relation to outcome variables. Before

intersection variables were generated, each variable had a dichotomous category. For example,

in EDHS, education status originally had four categories (no education, primary education,

secondary education, and tertiary education), dichotomised as non-educated and educated

(primary, secondary, and tertiary education) in this study. Similarly, wealth status originally

had five classes (poorest, poor, medium, rich, and richest), classified as poor (poorer and poor-

est) and rich (medium, richer, and richest) in the current study. The residence has urban and

rural categories. Thus, the categories of the triple intersectional variable are poor uneducated

rural (PUR), poor uneducated urban (PUU), poor uneducated rural (PER), poor educated

urban (PEU), rich uneducated rural (RUR), rich educated rural (RER), rich uneducated urban

(RUU), and rich educated urban (REU). Additionally, the categories of two intersectional vari-

ables are unemployed female, unemployed male, employed female, and employed male.

Other exploratory variables involved in the overall analysis of all outcome variables were

age category in years (15 to 19, 20 to 24, 25 to 29, 30 to 34, 35 to 39, 40 to 44, 45 to 49), marital

status (married, never married, widowed/divorced/no longer living together/separated), reli-

gion (orthodox, Catholic, Protestant, Muslim, others), sex of household head (male, female),

reading newspaper (no, yes), listening to the radio (no, yes), watching television (no, yes), and

region (Tigray, Afar, Amhara, Oromia, Somali, Benshangul-Gumuz, SNNPR, Gambela, Har-

ari, Addis Ababa, Dire Dawa). Region and variable due to the triple (dis)advantageous classes

were considered as community-level determinants. Other variables were considered as indi-

vidual-level determinants. Ever been tested for HIV (no, yes) was included in the analysis of

comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS and accepting attitude towards people living with

HIV. Comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS (no, yes) was included in the analysis of

accepting attitudes and HIV testing. Accepting attitudes towards people living with HIV (no,

yes) was included in the analysis of HIV testing.

Sampling technique and sample size

The 2016 Ethiopian Demographic and Health Survey (EDHS) followed the multistage sam-

pling method, which involves stratification, clustering, and sample selection over two stages

[45]. Urban and rural areas were grouped into nine regions and two city administrations as

the basis for stratification. Adults who gave consent and agreed to participate in the study

responded to the administered questionnaire. A total of 28,371 adults aged from 15 to 59 years

were interviewed in EDHS. However, 1,110 adults aged 50 years and above were excluded

because current study population was adults 15 to 49 years old. Therefore, the sample size was

27,261 for comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS. Regarding the sample size of accepting

attitudes towards people living with HIV, only those who aware of HIV/AIDS who were eligi-

ble for attitude-related questions. Based on this, 1,719 adults did not have awareness about

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 5 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

HIV/AIDS and were excluded from the attitudes-related questions. Therefore, 25,542 adults

participated to estimate intersectional inequity in accepting attitudes towards people living

with HIV. Similarly, the sample size for HIV testing was 25,542 because accepting attitude

towards people living with HIV was one of the independent variables in HIV testing. Thus,

participants eligible for attitude estimation were automatically eligible for intersectional ineq-

uity analysis in HIV testing. The recruitment period for study participants and data collection

period was from January to June 2016.

Data quality control

The EDHS data quality was assured with the provision of training for data collectors, supervi-

sors, and field editors, conducting ongoing supervision, using standardised and translated

questionnaires into national and local languages (e.g., Amharic, Oromiffa, Tigrigna) and data

processing specialists for data entry and management. A systematic bias was handled through-

out this phase [45]. After obtaining data from DHS, proper data management includes

appending women’s and men’s data, handling missed observations through missing

completely at random, recoding, and variable recategorisation was properly conducted.

Statistical analysis

Ethiopian demographic health survey has collected multilevel data at a hierarchical level. It is

important to note that we conducted the analysis after checking all the assumption. We

checked the Chi-square assumption test, including ‘expected value of cells should be 5 or

greater in at least 80% of cells’. Multilevel logistic regression is used to analyse multilevel data

with binary outcomes [52]. Thus, multilevel logistic regression analysis was run to estimate the

effect size of intersectional determinants (uneducated, poor and rural residents versus edu-

cated rich and urban resident) and unemployed women versus employed men. Residence,

education, wealth status, sex and employment status were excluded from multilevel analysis

because intersectional variables were established from these variables. The multicollinearity

test provided that the mean-variance inflation factor for variables fitted into the final model

was 1.26 (maximum 1.59 and minimum 1.07) for comprehensive knowledge about HIV/

AIDS, 1.25 (maximum 1.58 and minimum 1.08) for attitude towards people living with HIV,

and 1.25 (maximum 1.59 and minimum 1.08) for recent HIV testing and received test result.

Then, we compared intraclass correlation (ICC), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and

Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC) for the null-model, model-I (individual level determi-

nants), model-II (community-level determinants), and model-III (individual-and community-

level factors) (S1 Table). ‘The ICC quantifies the proportion of observed variation in the out-

comes that is attributable to the effect of clustering’ [52]. The current study denotes the varia-

tion in the knowledge, attitude, and HIV testing that is because of clustering. In the multilevel

logistic regression, region and triple intersectional variables were taken as community-level

variables. Finally, standard and multilevel logistic regression models were compared for AIC,

BIC and loglikelihood estimates. Generally, the lower AIC and BIC, and the higher loglikeli-

hood estimate was considered as best-fit model [53]. Adjusted odds ratio (aOR) and 95% con-

fidence interval (CI) with a P-value � 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

Ethics statement

Ethical approval was obtained from DHS (https://dhsprogram.com/). The University of

Queensland Institutional Ethical Review Board also exempted the ethical issue of this research

(approval project number: 2022/HE001760). Consent and confidentiality were responsibly

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 6 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

managed by the EDHS data collector team during data collection. To illustrate, informed con-

sent was obtained from parents to collect data from children [45].

Results

Participants characteristics

Comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS among adults, accepting attitude towards people

living with HIV, and HIV testing was 27.9% (95% CI: 26.5%, 29.3%), 39.8% (37.6, 41.9%), and

20.4% (95% CI: 19.1%, 21.8%), respectively. Comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS

among unemployed females was 17.6% and 38.9% among employed males. Accepting attitudes

among unemployed females was 32.1% and 44.1% among employed males. Recent HIV test

among unemployed females was 16.9% and 19.1% among employed males (Table 1).

Comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS among triple disadvantaged adults 15 to 49

years was 13.9% and 47.0% among triple advantaged. Accepting attitudes towards people living

with HIV was 16.0% among triple disadvantaged and 75.7% among triple advantaged. HIV

testing among triple disadvantaged adults was 7.7% and 35.9% among triple advantaged (Fig

2).

Intersectional determinants

The ICC in the null model implied that 13.7%, 29.1%, and 21.4% of the total variance in com-

prehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS, accepting attitudes towards people living with HIV,

and HIV testing, respectively, was credited to community-level determinants. In Model_I only

individual-related variables were included. The ICC in Model_I indicated that 9.7%, 17.9%,

and 14.0% of the variations of comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS, accepting attitudes

towards people living with HIV, and HIV testing, respectively, were accountable to differences

across community-level factors. In Model_II, only community-level factors were added. The

ICC showed that differences between community-level determinants account 6.1%, 11.0%,

and 7.7% of the variation for comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS, accepting attitude

towards people living with HIV, and HIV testing, respectively. In Model_III, both individual-

and community-level factors were included simultaneously. The ICC values of 6.3%, 10.9%,

and 9.2% of the variability in comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS, accepting attitudes

towards people living with HIV, and HIV testing, respectively, were accountable to differences

between community level factors (S1 Table).

Table 2 shows the multilevel logistic regression results of an association between indepen-

dents and outcome variables. Relative to adults with triple disadvantage (PUR), the odds of

comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS among adults with triple advantage (RUE) were

more than four-fold higher (aOR = 3.4; 95% CI: 2.76, 4.21) than their counterparts. Poor, edu-

cated, urban resident (PEU) adults had higher odds (aOR = 3.2; 95%CI = 1.39, 7.18) of com-

prehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS compared to adults with triple disadvantage. The

odds of comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS among rich, educated, rural resident

adults (RER) were two-fold higher (aOR = 2.0; 95% CI: 1.74, 2.40) than triple disadvantaged

groups. The odds of comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS among poor, educated and

rural residents (PER) were about two-fold higher (aOR = 1.8; 95% CI: 1.50, 2.05) than triple

disadvantage (PUR).

The odds of accepting attitudes towards people living with HIV among adults with triple

advantages REU were about seven-fold higher (aOR = 7.3; 95% CI: 5.79 to 9.24) than those

with triple disadvantages (poor, uneducated and rural). Similarly, poor adults with education

and residence advantage (PEU) had higher odds (aOR = 2.5; 95% CI = 1.23 to 5.12) of accept-

ing attitude towards people living with HIV compared to adults with triple disadvantage. The

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 7 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

Table 1. Characteristics of study participants and distribution of outcome variables across them in Ethiopia.

Variables Comprehensive knowledge Attitude towards People living HIV testing (n = 25,542)

about HIV/AIDS (n = 27,261) with HIV (n = 25,542)

Participant Yes (%) Participant Yes (%) Participant Yes (%)

Age in year

15–19 5,947 29.9 5,481 45.0 5,481 11.6

20–24 4,640 31.3 4,414 44.8 4,414 24.9

25–29 4,929 28.2 4,630 41.4 4,630 27.0

30–34 3,976 26.5 3,742 36.4 3,742 23.0

35–39 3,314 25.9 3,095 34.5 3,095 19.4

40–44 2,493 23.2 23,50 34.0 2,350 19.8

45–49 1,962 24.8 1,830 30.8 1,830 15.9

Sex

Men 11,594 38.3 11,160 45.2 11,160 19.4

Women 15,667 20.2 14,382 35.5 14,382 21.1

Residence

Urban 5,774 43.08 5,624 71.0 5,624 35.4

Rural 21,487 23.79 19,918 30.9 19,918 16.1

Marital status

Never married 8,909 35.6 8,384 52.0 8,384 16.3

Married and living together 16,648 24.1 15,593 32.9 15,592 22.0

Widowed/divorced/no longer living together/separated 1,704 24.1 1,566 42.7 1,566 25.7

Religion

Orthodox 11,934 33.2 11,442 48.8 11,442 25.1

Catholic 197 21.3 184 31.5 184 16.3

Protestant 6,228 25.8 5,898 32.2 5,898 15.9

Muslim 8,534 22.7 7,686 33.4 7,686 17.2

Others 368 15.2 332 13.0 332 13.3

Education status

Non-educated 10,690 15.2 9,560 22.0 9,560 14.6

Educated 16,571 36.0 15,982 50.4 15,982 23.8

Household wealth status

Poor 9,390 20.0 8,444 23.9 8,444 10.9

Rich 17,871 32.0 17,098 47.6 17,098 25.0

Employment status

Not employed 8,737 19.0 7,908 35.0 7,908 17.9

Employed 18,524 32.1 17, 634 41.9 17,634 21.5

Sex of household head

Male 22,009 27.2 20,630 37.4 20,630 19.8

Female 5,252 19.3 4,912 49.5 4,912 22.9

Reading newspaper

No 21,909 23.7 20,309 33.6 20,309 17.8

Yes 5,352 45.1 5,233 63.8 5,233 30.5

Listening to the radio

No 16,065 22.1 14,719 32.3 14,719 15.7

Yes 11,196 36.1 10, 823 49.8 10,823 26.8

Watching television

No 17,262 19.7 15,791 28.7 15,791 15.2

Yes 9,999 42.0 9,751 57.7 9,751 28.8

(Continued )

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 8 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

Table 1. (Continued)

Variables Comprehensive knowledge Attitude towards People living HIV testing (n = 25,542)

about HIV/AIDS (n = 27,261) with HIV (n = 25,542)

Participant Yes (%) Participant Yes (%) Participant Yes (%)

Region

Tigray 1,836 32.0 1,789 45.0 1,789 29.6

Afar 210 20.1 194 42.1 194 27.4

Amhara 6,622 31.7 6,369 46.3 6,369 22.5

Oromia 10,099 25.1 9,227 34.1 9,227 16.3

Somali 759 6.9 567 17.8 567 10.8

Benshangul-Gumuz 278 21.2 253 42.7 253 25.4

SNNPR 5,653 25.2 5,387 29.9 5,387 16.9

Gambela 78 31.2 73 56.9 73 37.1

Harari 67 26.4 63 58.7 63 23.6

Addis Ababa 1,502 31.3 1,474 64.4 1,474 37.1

Dire Dawa 157 46.9 146 80.4 146 39.8

Employment and Gender intersection

Unemployed female 7,812 17.6 7,057 32.1 7,057 18.5

Unemployed male 925 30.9 851 58.6 851 12.8

Employed female 7,856 22.7 7,325 38.8 7,325 23.7

Employed male 10,668 38.9 10,309 44.1 10,309 20.0

Triple intersection

Poor uneducated rural 5,277 13.9 4,573 16.0 4,573 7.7

Poor uneducated urban 98 19.4 88 33.3 88 19.4

Poor educated rural 3,892 27.9 3,663 33.5 3,663 12.8

Poor educated urban 123 32.5 120 34.2 120 11.4

Rich uneducated rural 4,662 16.0 4,277 24.5 4,277 16.5

Rich educated rural 7,657 33.2 7,405 42.6 7,405 20.7

Rich uneducated urban 653 19.1 622 48.6 622 34.8

Rich educated urban 4,899 47.0 4,794 75.7 4,794 35.9

Ever been tested for HIV

No 15,058 22.1 13,509 52.89 NA NA

Yes 12,202 35.0 12,033 47.11 NA NA

Comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS

No NA NA 18,049 31.6 18,049 18.1

Yes NA NA 7,493 59.4 7,493 25.8

Accepting attitude towards people living with HIV

No NA NA NA NA 15,389 15.9

Yes NA NA NA NA 10,153 27.2

NA: not applicable

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628.t001

odds of accepting attitudes among adults with wealth and education advantaged but rural resi-

dence (RER) were three- fold higher (aOR = 2.6; 95% CI: 2.11 to 3.11) than triple disadvantage

groups.

Discussion

The findings of this study suggest the presence of intersectional inequity, with significant dif-

ferences in knowledge about HIV/AIDS, attitude towards people living with HIV, and HIV

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 9 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

Fig 2. Comprehensive knowledge, accepting attitude, and HIV testing among adults 15 to 49 years with overlapping (dis)advantages in Ethiopia, 2016.

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628.g002

testing. Triple-disadvantaged groups have a lower accepting attitudes towards people living

with HIV, knowledge about HIV/AIDS, and HIV testing compared to other groups. Economic

and demographic determinants cannot solely explain inequity; comprehensive knowledge

about HIV/AIDS and having ever been tested for HIV significantly affect attitude towards peo-

ple living with HIV. Similarly, knowledge and attitude were precursors of recent HIV testing

and received test results.

The odds of comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS among unemployed females

(double disadvantages) were lower than among employed males (double advantages). In most

studies, gender was researched in intersectional inequity with other variables (e.g., race) [54].

Others added that gender influences health and behavioural characteristics [54–56]. It may

bring the research and programmes closer to gender-based intersectionality because historical

health disparities are recorded in these social categories. In all these cases, individuals with

multiple disadvantages lack services and suffer behavioural problems. Although employed

males had better knowledge about HIV/AIDS, they had a lower probability of receiving HIV

testing than unemployed females. This indicates the flexibility of intersectionality due to

males’ masculine behaviour. Despite controversial findings in the literature, males might have

lower health-seeking behaviour than females. For example, a study in Kenya concluded

women had lower health-seeking behaviour than men [57]. The UNAIDS also agreed that

HIV/AIDS inequities are attributed to the masculine behaviour of males, who thereby do not

use the expected extent of services [58].

Individuals with three non-advantageous social classes (uneducated, poor, and rural resi-

dents) also had a lower HIV/AIDS knowledge level and an accepting attitude towards people

living with HIV, as well as being less likely to undertake HIV testing. The current study also

found that poor rural residents who were educated, rich educated rural residents, and rich

uneducated urban residents had better knowledge, attitude, and HIV testing than people with

triple disadvantages. This study aligns with another study conducted in maternal care [26].

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 10 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

Table 2. Multilevel logistic regression analysis of variables to comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS, accepting attitude towards people living with HIV, and

HIV testing among adults 15 to 49 years in Ethiopia, 2016.

Variables Comprehensive knowledge about HIV/ Attitude towards people living HIV testing aOR

AIDS aOR (95% CI) with HIV aOR (95% CI) (95% CI)

Age (reference: 15–19 years)

20–24 1.10 (0.94, 1.28) 1.27 (1.10, 1.48)** 2.19 (1.81, 2.64)

***

25–29 1.03 (0.88, 1.21) 1.27 (1.06, 1.52)* 2.20 (1.76, 2.74)

***

30–34 1.15 (0.97, 1.37) 1.29 (1.07, 1.56)** 1.84 (1.45, 2.35)

***

35–39 1.19 (0.99, 1.44) 1.26 (1.03, 1.54)* 1.41 (1.11, 1.79)**

40–44 0.91 (0.74, 1.12) 1.17 (0.95, 1.45) 1.43 (1.09, 1.88)**

45–49 1.10 (0.88, 1.37) 1.04 (0.82, 1.33) 1.05 (0.77, 1.43)

Marital status (reference: married)

Never married 1.21 (1.07, 1.38)** 1.44 (1.25, 1.66)*** 0.48 (0.41, 0.56)

***

Widowed/divorced/no longer living together/separated 0.94 (0.79, 1.12) 1.10 (0.91, 1.34) 0.86 (0.69, 1.06)

Religion (reference: Orthodox)

Catholic 0.74 (0.44, 1.25) 1.08 (0.59, 1.96) 0.62 (0.34, 1.14)

Protestant 0.91 (0.73, 1.15) 0.91 (0.74, 1.11) 0.90 (0.71, 1.13)

Muslim 1.04 (0.91, 1.19) 0.91 (0.76, 1.09) 1.11 (0.90, 1.38)

Others 0.74 (0.41, 1.33) 0.39 (0.17, 0.88)* 1.12 (0.66, 1.92)

Sex of household head (reference: male)

Female 1.13 (1.003, 1.27)* 1.16 (1.03, 1.31)* 1.07 (0.94, 1.22)

Reading newspapers (reference: No)

Yes 1.23 (1.10, 1.34)*** 1.62 (1.41, 1.85)*** 1.26 (1.11, 1.43)

***

Listening to the radio (reference: No)

Yes 1.03 (0.92, 1.15) 1.06 (0.89, 1.14) 1.34 (1.19, 1.51)

***

Watching television (reference: No)

Yes 1.45 (1.27, 1.67)*** 1.26 (1.11, 1.44)*** 1.10, 0.96, 1.27)

Gender & employment intersection (Reference: unemployed

female)

Unemployed male 1.39 (1.08, 1.78)* 1.72 (1.34, 2.22)*** 0.64 (0.45, 0.91)*

Employed female 1.12 (0.98, 1.28) 1.01 (0.86, 1.19) 0.97 (0.85, 1.11)

Employed male 2.43 (2.07, 2.85)*** 1.25 (0.99, 1.58) 0.85 (0.73, 0.98)*

Region (reference: Addis Ababa)

Tigray 1.25 (1.01, 1.55)* 0.76 (0.57, 1.04) 1.68 (1.34, 2.12)

***

Afar 0.75 (0.55, 1.03) 0.99 (0.71, 1.39) 1.52 (1.13, 2.04)**

Amhara 1.35 (1.10, 1.65)** 1.00 (0.77, 1.31) 1.16 (0.94, 1.44)

Oromia 0.99 (0.80, 1.23) 0.55 (0.40, 0.76)*** 0.59 (0.45, 0.78)

***

Somali 0.28 (0.20, 0.37)*** 0.29 (0.21, 0.40)*** 0.52 (0.37, 0.74)

***

Benshangul-Gumuz 0.76 (0.60, 0.97)* 0.92 (0.68, 1.24) 1.32 (1.004, 1.76)

*

SNNPR 1.08 (0.84, 1.38) 0.50 (0.38, 0.68)*** 0.88 (0.67, 1.14)

Gambela 0.92 (0.73, 1.16) 0.96 (0.69, 1.32) 1.87 (1.45, 2.41)

***

Harari 0.66 (0.49, 0.89)** 0.97 (0.74, 1.27) 0.68 (0.53, 0.87)**

(Continued )

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 11 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

Table 2. (Continued)

Variables Comprehensive knowledge about HIV/ Attitude towards people living HIV testing aOR

AIDS aOR (95% CI) with HIV aOR (95% CI) (95% CI)

Dire Dawa 0.66 (0.49, 0.90)* 0.96 (0.74, 1.23) 1.58 (1.27, 1.96)

***

Triple intersection based on wealth index, education, residence

status (reference: Poor uneducated rural (PUR))

Poor uneducated urban (PUU) 1.64 (0.83, 3.27) 1.65 (0.70, 3.87) 3.34 (1.01, 11.12)

*

Poor educated rural (PER) 1.75 (1.50, 2.05)*** 2.07 (1.68, 2.54)*** 1.80 (1.45, 2.22)

***

Poor educated urban (PEU) 3.16 (1.39, 7.18)** 2.51 (1.23, 5.12)*** 2.22 (0.86, 5.78)

Rich uneducated rural (RUR) 1.00 (0.83, 1.21) 1.35 (1.12, 1.64)** 1.86 (1.51, 2.30)

***

Rich educated rural (RER) 2.04 (1.74, 2.40)*** 2.56 (2.11, 3.11)*** 2.67 (2.15, 3.31)

***

Rich uneducated urban (RUU) 1.27 (0.90, 1.79) 3.60 (2.66, 4.88)*** 4.84 (3.59, 6.54)

***

Rich educated urban (REU) 3.41 (2.76, 4.21)*** 7.3 (5.79, 9.24)*** 4.69 (3.60, 6.10)

***

Ever been tested for HIV (reference: No)

Yes 1.38 (1.25, 1.55)*** 1.34 (1.21, 1.49)*** _

Comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS (Reference: No)

Yes _ 2.06 (1.85, 2.31)*** 1.17 (1.04, 1.30)**

Accepting attitude towards people living with HIV (reference:

No)

Yes _ _ 1.18 (1.05, 1.31)**

* p-value�0.05;

** p-value�0.01;

*** p-value�0.00;

SNNPR: Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628.t002

Maternal care and HIV/AIDS services are indeed distinct arenas. Still, the social categories for

the intersectionality approach have followed similar methods and analyses. Women with triple

disadvantages were less likely to attend antenatal and postnatal care [26], similar to the current

study. There could be a higher probability that an individual with triple better living conditions

(urban resident, educated and rich) has higher intersecting opportunities in living conditions,

accessing health information, behavioural change services, and clinical interventions. This is

because each advantageous living character’s combined opportunities, resources, and power

greatly improved behaviour, service coverage, and health outcomes. Urban, better-educated,

and individuals in the higher economic class are usually near healthcare because they reside

around healthcare settings, have better knowledge about health problems, and can cover direct

and indirect healthcare expenditures [59]. In the Ethiopian context, the more educated reside

in urban areas and have a higher income, which reflects the interrelationship between each cat-

egory [60, 61].

Congruent with existing research, the current findings are also in agreement with how

HIV/AIDS was assessed at the intersection of race or ethnicity (Latina) and culture or language

(monolingual) [12]. In both studies, those with the intersection of disadvantageous identities

had a lower level of HIV/AIDS knowledge as compared to their counterparts. Additionally,

Ghasemi et al. found that those with triple disadvantages were more likely to experience HIV-

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 12 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

related stigma in Iran [31]. In the current and previous studies, intersectional inequity was

profound despite different intersectional determinants. This implies that intersectionality

works in different healthcare contexts, revealing that the more disadvantaged social identity

has the least service accessibility.

Improving the living conditions of communities is essential, especially by addressing multi-

dimensional poverty, enhancing education, and tackling inequalities. Low-income adults face

various disadvantages across multiple dimensions, with poverty significantly intersecting with

health, education, and overall living conditions. The United Nations Development Programme

(UNDP) emphasizes the need for countries to prioritize improving living conditions to pro-

mote a healthier population. Notably, a report covering 110 countries reveals that 25 of them

successfully halved multidimensional poverty within 15 years. Despite this progress, 17.0%

(1.1 billion out of 6.1 billion people) still live in poverty. Of these 1.1 billion individuals, 534

million reside in sub-Saharan Africa [62]. The UNDP further underscores the importance of

examining why people are left behind, empowering them, and implementing policies and

reforms to address the drivers of poverty [63].

The current finding marks a turning point in embracing intersectionality in policy and clin-

ical services. Therefore, the recent evidence suggests a need for a more nuanced emphasis on

people with multiple disadvantages. Intersectional inequity should be emphasised in policy

formulation and implementation, the health service system, the research environment, and

health academics towards knowledge, attitude, and testing in the HIV/AIDS continuum. To

integrate this finding into programmes and practises, emphasis should be given first to triple-

disadvantaged groups, followed by double- and single-disadvantaged groups. This means

interventions to narrow disparities may not be uniform for urban and rural populations,

which is important for international and national initiatives. For example, UNAIDS intro-

duced ‘education plus’ initiatives to be implemented from 2021 to 2025, which focus on ado-

lescent girls and young women to achieve gender equality in preventing HIV [64]. Thus,

implementing this initiative can consider girls who live in lower-income households, lower

grade levels, and rural areas (one girl has these three conditions at a time) in the first round of

services. The interventions aimed at enhancing knowledge about HIV/AIDS, ending stigma

and discrimination, and expanding HIV testing coverage are also essential in addressing inter-

sectional inequity. It is essential to adopt culturally sensitive and contextually relevant inter-

ventions. These might involve training initiatives and research activities, especially in low- and

middle-income countries [10]. The UNDP highlights intersectional determinants, including

geography, discrimination, poverty, race, and socioeconomic status. However, some of these

factors were not addressed in the current study. Therefore, it is crucial for future researchers to

explore intersectionality from multiple dimensions. For instance, examining the intersection

of female widows, sex workers, daily labourers, factory workers, long-distance travellers, and

other vulnerable groups in the context of fighting HIV/AIDS is essential, as these individuals

face a high risk of HIV infection [65].

Strengths and limitations

The current study is the first of its kind in HIV/AIDS services, and the intersectional subgroup

variables had a sufficient sample size, which is likely to minimise random error. Hence, it

solved the literature gap in low-income countries, particularly in Ethiopia, because the scarcity

of intersectionality evidence challenged its implementation in low-income countries [66].

As to the limitations, knowledge, attitude, and HIV testing were measured based on respon-

dents’ self-report, which is prone to recall bias. Second, a cross-sectional study design has a

‘chicken-egg’ dilemma scenario; thus, the current findings cannot represent a cause-and-effect

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 13 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

relationship [67]. Third, some structural and health system determinants were not considered

in the analysis because EDHS has not included governance and leadership, policies, and health

systems’ variables about HIV/AIDS indicators. Fourth, the UNAIDS has implemented a com-

bination HIV prevention program, which encompasses behavioural interventions (e.g., coun-

selling and education program), biomedical services (e.g., HIV testing), and structural

interventions (e.g., initiatives to reduce stigma and discrimination) [2]. We have tried to incor-

porate these three programmes in a manner that allows for measurable evaluation. Inequities

in health services may reflects an unfair distribution of resources. Hence, in our study, careful

consideration may be required to understand the inequity in accepting attitudes towards peo-

ple living with HIV and knowledge about HIV/AIDS because these are not services but rather

outcomes of certain interventions. An intervention aimed at addressing stigma and discrimi-

nation entails fostering accepting attitudes towards people living with HIV. This implies that

an individual with lower accepting attitudes may require structural intervention to reduce

stigma and discrimination. Similarly, a lower knowledge about HIV/AIDS may reflect a gap in

the counselling and education interventions.

Conclusions

Triple-disadvantaged groups have a lower accepting attitude towards people living with HIV,

comprehensive knowledge about HIV/AIDS, and recent HIV testing. Using intersectionality

as an equity lens will allow reaching populations belonging to multiple disadvantages. If the

intersectional inequity concept is included in the health policy statement, the triple disadvan-

taged (rural and uneducated and poor) will receive equity-based health care intervention first,

followed by the double disadvantaged (e.g., rural and poor and educated), and finally the single

disadvantaged (as usual).

It is necessary to design a strategy for achieving equity among people with multiple disad-

vantages. A combination of individual and public health measures should be delivered with

wider attempts to address multiple forms of inequity. Additionally, prioritise intersectionality

and inequity as a new agenda to consider at clinical, research, and policy levels sustainably. To

understand intersectionality at the macro- and policy-level, a critical HIV/AIDS policy evalua-

tion is required.

Supporting information

S1 Table. Intraclass correlation (ICC), Akaike Information Criterion (AIC) and Bayesian

Information Criterion (BIC) for the null-model, model-I (individual level determinants),

model-II (community-level determinants), and model-III (individual-and community-

level factors).

(PDF)

S1 Checklist. STROBE checklist: Research reporting checklist for cross-sectional studies.

(DOCX)

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Aklilu Endalamaw.

Data curation: Aklilu Endalamaw.

Formal analysis: Aklilu Endalamaw.

Investigation: Aklilu Endalamaw.

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 14 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

Methodology: Aklilu Endalamaw.

Project administration: Aklilu Endalamaw.

Software: Aklilu Endalamaw.

Supervision: Charles F. Gilks, Yibeltal Assefa.

Validation: Aklilu Endalamaw, Resham B. Khatri, Yibeltal Assefa.

Visualization: Aklilu Endalamaw, Charles F. Gilks, Yibeltal Assefa.

Writing – original draft: Aklilu Endalamaw.

Writing – review & editing: Aklilu Endalamaw, Charles F. Gilks, Resham B. Khatri, Yibeltal

Assefa.

References

1. Watkins-Hayes C. Intersectionality and the sociology of HIV/AIDS: Past, present, and future research

directions. Annual Review of Sociology. 2014; 40:431–57.

2. UNAIDS. Combination HIV Prevention: Tailoring and Coordinating Biomedical, Behavioural and Struct

ural Strategies to Reduce New HIV Infections. UNAIDS. Geneva, Switzerland: UNAIDS; 2010.

3. UNAIDS. Understanding Fast-Track: Accelerating action to end the AIDS epidemic by 2030 Geneva,

Switzerland: Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2015 [https://www.unaids.org/sites/

default/files/media_asset/201506_JC2743_Understanding_FastTrack_en.pdf.

4. Federal HIV/AIDS Prevention and Control Office. HIV/AIDS National Strategic Plan for Ethiopia 2021 to

2025. Addis Ababa, Ethiopia.

5. UNAIDS. GLOBAL AND REGIONAL DATA: Building on two decades of progress against AIDS.

Geneva, Switzerland; 2021.

6. Kene C, Deribe L, Adugna H, Tekalegn Y, Seyoum K, Geta G. HIV/AIDS related knowledge of univer-

sity students in Southeast Ethiopia: a cross-sectional survey. HIV/AIDS-Research and Palliative Care.

2021:681–90. https://doi.org/10.2147/HIV.S300859 PMID: 34168506

7. Gebremedhin H, Gebremedhin H, Desse A, Alemayehu M, Abreha H, Berhane Y, et al. Attitude and

Misconception towards HIV/AIDS and Associated Factors among early adolescent students in North

Ethiopia. European journal of pharmaceutical and medical research, Ejpmr. 2016; 3(4):1–8.

8. Diress GA, Ahmed M, Linger M. Factors associated with discriminatory attitudes towards people living

with HIV among adult population in Ethiopia: analysis on Ethiopian demographic and health survey.

SAHARA-J: Journal of Social Aspects of HIV/AIDS. 2020; 17(1):38–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/

17290376.2020.1857300 PMID: 33357027

9. Antabe R, Sano Y, Atuoye KN, Baada JN. Determinants of HIV-related stigma and discrimination in

Malawi: evidence from the demographic and health survey. African Geographical Review. 2023; 42

(5):594–606.

10. Majeed T, Hopkin G, Wang K, Nepal S, Votruba N, Gronholm P, et al. Anti-stigma interventions in low-

income and middle-income countries: a systematic review. EClinicalMedicine. 2024; 72. https://doi.org/

10.1016/j.eclinm.2024.102612 PMID: 38707913

11. Endalamaw A, Geremew D, Alemu SM, Ambachew S, Tesera H, Habtewold TD. HIV test coverage

among pregnant women in Ethiopia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. African Journal of AIDS

Research. 2021; 20(4):259–69. https://doi.org/10.2989/16085906.2021.1980066 PMID: 34905450

12. Rountree MA, Granillo T, Bagwell-Gray M. Promotion of Latina health: Intersectionality of IPV and risk

for HIV/AIDS. Violence against women. 2016; 22(5):545–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/

1077801215607358 PMID: 26472666

13. Dadi TK, Feyasa MB, Gebre MN. HIV knowledge and associated factors among young Ethiopians:

application of multilevel order logistic regression using the 2016 EDHS. BMC Infectious Diseases.

2020; 20(1):1–11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-020-05436-2 PMID: 32993536

14. Endalamaw A, Gilks CF, Ambaw F, Khatri RB, Assefa Y. Socioeconomic inequality in knowledge about

HIV/AIDS over time in Ethiopia: A population-based study. PLOS Global Public Health. 2023; 3(10):

e0002484. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0002484 PMID: 37906534

15. Ante-Testard PA, Benmarhnia T, Bekelynck A, Baggaley R, Ouattara E, Temime L, et al. Temporal

trends in socioeconomic inequalities in HIV testing: an analysis of cross-sectional surveys from 16 sub-

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 15 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

Saharan African countries. The Lancet global health. 2020; 8(6):e808–e18. https://doi.org/10.1016/

S2214-109X(20)30108-X PMID: 32446346

16. Holman D, Salway S, Bell A, Beach B, Adebajo A, Ali N, et al. Can intersectionality help with under-

standing and tackling health inequalities? Perspectives of professional stakeholders. Health Research

Policy and Systems. 2021; 19(1):97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12961-021-00742-w PMID: 34172066

17. Bauer GR, Churchill SM, Mahendran M, Walwyn C, Lizotte D, Villa-Rueda AA. Intersectionality in quan-

titative research: A systematic review of its emergence and applications of theory and methods. SSM-

population health. 2021; 14:100798. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ssmph.2021.100798 PMID: 33997247

18. Caiola C, Docherty S, Relf M, Barroso J. Using an intersectional approach to study the impact of social

determinants of health for African-American mothers living with HIV. ANS Advances in nursing science.

2014; 37(4):287. https://doi.org/10.1097/ANS.0000000000000046 PMID: 25365282

19. Hu X, Wang T, Huang D, Wang Y, Li Q. Impact of social class on health: The mediating role of health

self-management. Plos one. 2021; 16(7):e0254692. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0254692

PMID: 34270623

20. Pfautz HW. The current literature on social stratification: critique and bibliography. University of Chi-

cago Press; 1953.

21. Morrow M, Bryson S, Lal R, Hoong P, Jiang C, Jordan S, et al. Intersectionality as an analytic framework

for understanding the experiences of mental health stigma among racialized men. International Journal

of Mental Health and Addiction. 2020; 18:1304–17.

22. Crenshaw K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A Black feminist critique of antidiscrimi-

nation doctrine, feminist theory, and antiracist politics Feminist legal theory: Routledge; 1989. p. 57–80.

23. Hurtado A. Intersectional understandings of inequality. The Oxford handbook of social psychology and

social justice. 2018:157–87.

24. Hogan JW, Galai N, Davis WW. Modeling the impact of social determinants of health on HIV. AIDS and

Behavior. 2021; 25(2):215–24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-021-03399-2 PMID: 34478016

25. Braveman P, Gottlieb L. The social determinants of health: it’s time to consider the causes of the

causes. Public health reports. 2014; 129(1_suppl2):19–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/

00333549141291S206 PMID: 24385661

26. Khatri RB, Alemu Y, Protani MM, Karkee R, Durham J. Intersectional (in) equities in contact coverage of

maternal and newborn health services in Nepal: insights from a nationwide cross-sectional household

survey. BMC public health. 2021; 21(1):1098. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11142-8 PMID:

34107922

27. Bauer GR. Incorporating intersectionality theory into population health research methodology: chal-

lenges and the potential to advance health equity. Social science & medicine. 2014; 110:10–7. https://

doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.022 PMID: 24704889

28. Bowleg L. The problem with the phrase women and minorities: intersectionality—an important theoreti-

cal framework for public health. American journal of public health. 2012; 102(7):1267–73. https://doi.

org/10.2105/AJPH.2012.300750 PMID: 22594719

29. Collins PH. Black feminist thought: Knowledge, consciousness, and the politics of empowerment: rout-

ledge; 2002.

30. Woodgate RL, Zurba M, Tennent P, Cochrane C, Payne M, Mignone J. A qualitative study on the inter-

sectional social determinants for indigenous people who become infected with HIV in their youth. Inter-

national journal for equity in health. 2017; 16(1):1–12.

31. Ghasemi E, Rajabi F, Negarandeh R, Vedadhir A, Majdzadeh R. HIV, migration, gender, and drug

addiction: A qualitative study of intersectional stigma towards Afghan immigrants in Iran. Health & social

care in the community. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1111/hsc.13622 PMID: 34725886

32. Mburu G, Ram M, Siu G, Bitira D, Skovdal M, Holland P. Intersectionality of HIV stigma and masculinity

in eastern Uganda: implications for involving men in HIV programmes. BMC public health. 2014; 14

(1):1–9. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-14-1061 PMID: 25304035

33. Hankivsky O. Intersectionality 101. The Institute for Intersectionality Research & Policy, SFU; 2014.

34. Hancock A-M. When multiplication doesn’t equal quick addition: Examining intersectionality as a

research paradigm. Perspectives on politics. 2007; 5(1):63–79.

35. Lacombe-Duncan A. An Intersectional Perspective on Access to HIV-Related Healthcare for Transgen-

der Women. Transgender health. 2016; 1(1):137–41. https://doi.org/10.1089/trgh.2016.0018 PMID:

29159304

36. Yoshida K, Hanass-Hancock J, Nixon S, Bond V. Using intersectionality to explore experiences of dis-

ability and HIV among women and men in Zambia. Disability and rehabilitation. 2014; 36(25):2161–8.

https://doi.org/10.3109/09638288.2014.894144 PMID: 24597938

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 16 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

37. World Health Organization. Tracking universal health coverage: first global monitoring report: World

Health Organization; 2015.

38. UNAIDS. Global AIDS strategy 2021–2026: end inequalities. Geneva, Switzerland; 2021.

39. Lokot M, Avakyan Y. Intersectionality as a lens to the COVID-19 pandemic: implications for sexual and

reproductive health in development and humanitarian contexts. Sexual and Reproductive Health Mat-

ters. 2020; 28(1):1764748. https://doi.org/10.1080/26410397.2020.1764748 PMID: 32366190

40. Harari L, Lee C. Intersectionality in quantitative health disparities research: a systematic review of chal-

lenges and limitations in empirical studies. Social Science & Medicine. 2021; 277:113876. https://doi.

org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2021.113876 PMID: 33866085

41. World Population Prospects (2022 revision) - United Nations Population estimatos and projections.

Accessed 24 April 2023 https://worldpopulationreview.com/countries/ethiopia-population

42. Foundation LI. The Legatum Prosperity Index: Creating the Pathways from Poverty to Prosperity

[https://www.prosperity.com/globe/ethiopia.

43. Saifaddin Galal. Gender gap index in Ethiopia in 2021 2021 [https://www.statista.com/statistics/

1253877/gender-gap-index-in-ethiopia-by-sector/#:~:text=In%202021%2C%20Ethiopia%20had%

20an,of%20females%20in%20the%20country.

44. Worldometer. Ethiopia Population [cited 2023 15 June]. https://www.worldometers.info/world-

population/ethiopia-population/.

45. Central Statistical Agency and ICF. EThiopia Demographic and Health Survey 2016. Addis Ababa Ethi-

opia and Rockville, Maryland, USA; 2017.

46. World Health Organization. A conceptual framework for action on the social determinants of health

Geneva: World Health Organization; 2010 [https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/44489/

9789241500852_eng.pdf.

47. Commission of the Pan American Health Organization on Equity and Health Inequalities in the Ameri-

cas. Just Societies: Health Equity and Dignified Lives. Report of the Commission of the Pan American

Health Organization on Equity and Health Inequalities in the Americas. Washington, D.C.: PAHO; 2019.

48. USAID from the American People. Guide to DHS Statictics: DHS-7 (version 2)-The Demographic

Health survey Program [cited 2023 15 June]. https://dhsprogram.com/Data/Guide-to-DHS-Statistics/

index.cfm.

49. Croft T N, Aileen M. Marshall J., Courtney K. Allen, et al. 2018. Guide to DHS Statistics. Rockville,

Maryland, USA: ICF. Guide to DHS Statistics [https://dhsprogram.com/data/Guide-to-DHS-Statistics/

index.cfm.

50. International Labour Organization. The gender gap in employment: What’s holding women back? Uni-

tes States2017 [updated February 2022; cited 2023 31 May]. https://www.ilo.org/infostories/en-GB/

Stories/Employment/barriers-women#intro.

51. Maulsby CH, Ratnayake A, Hesson D, Mugavero MJ, Latkin CA. A scoping review of employment and

HIV. AIDS and Behavior. 2020; 24:2942–55. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10461-020-02845-x PMID:

32246357

52. Austin PC, Merlo J. Intermediate and advanced topics in multilevel logistic regression analysis. Statis-

tics in medicine. 2017; 36(20):3257–77. https://doi.org/10.1002/sim.7336 PMID: 28543517

53. Chakrabarti A, Ghosh JK. AIC, BIC and recent advances in model selection. Philosophy of statistics.

2011:583–605.

54. Rao D, Andrasik MP, Lipira L. HIV stigma among black women in the United States: intersectionality,

support, resilience. American Public Health Association; 2018. p. 446–8.

55. Kim SS, DeMarco RF. The Intersectionality of HIV-Related Stigma and Tobacco Smoking Stigma With

Depressive and Anxiety Symptoms Among Women Living With HIV in the United States: A Cross-sec-

tional Study. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care. 2022; 33(5):523–33. https://doi.org/10.

1097/JNC.0000000000000323 PMID: 34999667

56. Konkor I, Lawson ES, Antabe R, McIntosh MD, Husbands W, Wong J, et al. An intersectional approach

to HIV vulnerabilities and testing among heterosexual african caribbean and Black men in London,

Ontario: results from the weSpeak study. Journal of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2020; 7:1140–

9. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40615-020-00737-3 PMID: 32212106

57. Voeten HA, O’hara HB, Kusimba J, Otido JM, Ndinya-Achola JO, Bwayo JJ, et al. Gender differences in

health care-seeking behavior for sexually transmitted diseases: a population-based study in Nairobi,

Kenya. Sexually transmitted diseases. 2004:265–72. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.olq.0000124610.

65396.52 PMID: 15107627

58. UNAIDS. Dangerous inequalities: World AIDS Day report Geneva, Switzerland: Joint United Nations

Programme on HIV/AIDS; 2022 [https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/dangerous-

inequalities_en.pdf.

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 17 / 18

PLOS GLOBAL PUBLIC HEALTH Intersectional inequity in knowledge, attitude, and testing related to HIV

59. Poudel AN, Newlands D, Simkhada P. The economic burden of HIV/AIDS on individuals and house-

holds in Nepal: a quantitative study. BMC health services research. 2017; 17(1):1–13.

60. Hussen NM, Workie DL. Multilevel analysis of women’s education in Ethiopia. BMC Women’s Health.

2023; 23(1):197. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12905-023-02380-6 PMID: 37106332

61. Teshome G, Sera L, Dachito A. Determinants of income inequality among urban households in Ethio-

pia: a case of Nekemte Town. SN Business & Economics. 2021; 1:1–21.

62. United Nations Development Programme. 2023 Global Multidimensional Poverty Index (MPI) 2023

[updated July 11, 2023. https://hdr.undp.org/content/2023-global-multidimensional-poverty-index-mpi#/

indicies/MPI.

63. United Nations Development Programme. What does it mean to leave no one behind? A UNDP discus-

sion paper and framework for implementation July 2018.

64. UNAIDS. The ‘Education plus’ initiative (2021–2025) - empowerment of adolescent girls and young

women in sub-Saharan Africa: UNAIDS; [https://www.unaids.org/en/topics/education-plus.

65. UNAIDS. IN DANGER: UNAIDS Global AIDS Update 2022. Geneva: Joint United Nations Programme

on HIV/AIDS; 2022. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO.

66. Rojas-Garcı́a A, Holman D, Tinner L, Ejegi-Memeh S, Ben-Shlomo Y, Laverty AA. Use of intersectional-

ity theories in interventional health research in high-income countries: a systematic scoping review. The

Lancet. 2022; 400:S58.

67. Di Girolamo N, Mans C. Research study design. Fowler’s Zoo and Wild Animal Medicine Current Ther-

apy, Volume 9: Elsevier; 2019. p. 59–62.

PLOS Global Public Health | https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0003628 August 22, 2024 18 / 18

You might also like

- Letter of Request For Fogging and MistingDocument2 pagesLetter of Request For Fogging and MistingDoc Marshall90% (10)

- HIv FertilityDocument10 pagesHIv FertilityAmalia RiaNo ratings yet

- Lived Experiences of Adolescents Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus in NamibiaDocument10 pagesLived Experiences of Adolescents Living With Human Immunodeficiency Virus in NamibiaIJPHS100% (1)

- ajol-file-journals_56_articles_115334_submission_proof_115334-661-321188-1-10-20150408Document10 pagesajol-file-journals_56_articles_115334_submission_proof_115334-661-321188-1-10-20150408GAD PATRICK IRADUKUNDANo ratings yet

- Navigating Disclosure Obstacles Encountered by Individuals With HIV at Kakomo Healing Centre IV in Kabale DistrictDocument15 pagesNavigating Disclosure Obstacles Encountered by Individuals With HIV at Kakomo Healing Centre IV in Kabale DistrictKIU PUBLICATION AND EXTENSIONNo ratings yet

- Artikel-Hiv-Ayu NingrumDocument7 pagesArtikel-Hiv-Ayu NingrumAyu NingrumNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS Among Adolescents 169 PDFDocument10 pagesEpidemiology of HIV and AIDS Among Adolescents 169 PDFPAUL AYAMAHNo ratings yet

- Determinantes VG EtiopiaDocument18 pagesDeterminantes VG EtiopiaTatiana SandovalNo ratings yet

- Pone 0277178Document18 pagesPone 0277178Beshir IdaoNo ratings yet

- Awareness of HIV/AIDS Among Grade 10 Students in Teofilo V. Fernandez National High SchoolDocument18 pagesAwareness of HIV/AIDS Among Grade 10 Students in Teofilo V. Fernandez National High SchoolChristine Jean CeredonNo ratings yet

- Hiv Pinakafinal Na February EditingDocument58 pagesHiv Pinakafinal Na February EditingKaren Mae Santiago AlcantaraNo ratings yet

- VIH/SIDA - RevelacaoDocument7 pagesVIH/SIDA - Revelacaovanessa waltersNo ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitude, and Practice Towards Ethiopia 2020Document15 pagesKnowledge, Attitude, and Practice Towards Ethiopia 2020adhiniNo ratings yet

- Ambo UniversityDocument12 pagesAmbo UniversityArarsa TolasaNo ratings yet

- 1-HIV AIDS Knowledge Behaviour and BeliefsDocument6 pages1-HIV AIDS Knowledge Behaviour and BeliefsNhat Khanh TranNo ratings yet

- Tropical Med Int Health - 2019 - Finlay - Sexual and Reproductive Health Knowledge Among Adolescents in Eight Sites AcrossDocument10 pagesTropical Med Int Health - 2019 - Finlay - Sexual and Reproductive Health Knowledge Among Adolescents in Eight Sites AcrossAhmed AbbasNo ratings yet

- Reach People With AidsDocument6 pagesReach People With AidsLito GallegoNo ratings yet

- Association of Hiv Knowledge Testing Attitudes and Risk AssessmentDocument8 pagesAssociation of Hiv Knowledge Testing Attitudes and Risk AssessmentALEXANDRANICOLE OCTAVIANONo ratings yet

- Rowena Anchor PaperDocument10 pagesRowena Anchor PaperjoluksNo ratings yet

- Epidemiology of HIV and AIDS Among Adolescents 169Document10 pagesEpidemiology of HIV and AIDS Among Adolescents 169Genevieve Caecilia Linda KNo ratings yet

- Influence of HIV Testing On Knowledge of HIV AIDS Prevention Practices and Transmission Among Undergraduate Youths in North West UniDocument16 pagesInfluence of HIV Testing On Knowledge of HIV AIDS Prevention Practices and Transmission Among Undergraduate Youths in North West UniGabz GabbyNo ratings yet

- 10 - Dwiti Hikmah Sari - 16ik466Document11 pages10 - Dwiti Hikmah Sari - 16ik466titi hikmahsariNo ratings yet

- Journal of The International AIDS Society - 2023 - Bernays - They Test My Blood To Know How Much Blood Is in My Body TheDocument9 pagesJournal of The International AIDS Society - 2023 - Bernays - They Test My Blood To Know How Much Blood Is in My Body TheFiraol MesfinNo ratings yet

- Dual Contraceptives and Associated Predictors in HIV Positive WomenDocument13 pagesDual Contraceptives and Associated Predictors in HIV Positive WomenTopaz Mulia abadiNo ratings yet

- Chapter One 1.1 Background To The StudyDocument30 pagesChapter One 1.1 Background To The StudyJafar Abdullahi SufiNo ratings yet

- Researcharticle Open AccessDocument13 pagesResearcharticle Open AccessChristian MolimaNo ratings yet

- 3574-Article Text-80905-1-10-20220927Document8 pages3574-Article Text-80905-1-10-20220927Assuming AssumingxdNo ratings yet

- 7.env Eco - IJEEFUS - HIV - Ghasem GhojavandDocument8 pages7.env Eco - IJEEFUS - HIV - Ghasem GhojavandTJPRC PublicationsNo ratings yet

- Christine Jean Ceridon-1 FINAL (Autosaved) - 1Document40 pagesChristine Jean Ceridon-1 FINAL (Autosaved) - 1Christine Jean CeredonNo ratings yet

- ProposalDocument22 pagesProposalbegosewNo ratings yet

- CYNTHIADocument44 pagesCYNTHIAedmondNo ratings yet

- Among Youth: Hiv/AidsDocument5 pagesAmong Youth: Hiv/AidsShahnaz RizkaNo ratings yet

- 4_5828172961705625404Document30 pages4_5828172961705625404Semon YohannesNo ratings yet

- AFHS2004-1582Document9 pagesAFHS2004-1582sylvanuskennedy007No ratings yet

- HIVAR Art 39965-10Document6 pagesHIVAR Art 39965-10landoo oooNo ratings yet

- Exploring Barriers and Facilitators of Adherence to AntiretroviralDocument40 pagesExploring Barriers and Facilitators of Adherence to Antiretroviralmmbc2788No ratings yet

- Knowledge, Attitude, and Willingness of Nursing Students Towards HIV/AIDS Patient Care: A Descriptive StudyDocument9 pagesKnowledge, Attitude, and Willingness of Nursing Students Towards HIV/AIDS Patient Care: A Descriptive StudyEndy SitumbekoNo ratings yet

- Adolesecents Perspective: Hiv/Aids Infection and Prevention in The PhilippinesDocument11 pagesAdolesecents Perspective: Hiv/Aids Infection and Prevention in The Philippinesjoanne riveraNo ratings yet

- Final Papers QuantitativeDocument95 pagesFinal Papers QuantitativeDahl xxNo ratings yet

- Journal Pone 0257906Document18 pagesJournal Pone 02579062359603No ratings yet

- HIV/AIDS Awareness Evaluation in The Junior and Senior High School Students of University of The East Caloocan (UEC)Document11 pagesHIV/AIDS Awareness Evaluation in The Junior and Senior High School Students of University of The East Caloocan (UEC)Sebastian Miguel CarlosNo ratings yet

- 2013 Article 326Document8 pages2013 Article 326Ariyati MandiriNo ratings yet

- International Archives of Nursing and Health Care Ianhc 10 195Document12 pagesInternational Archives of Nursing and Health Care Ianhc 10 195Rose Mmusi-PhetoeNo ratings yet

- Knowledge of HIV/AIDS and The Use of Contraceptives (Condom) As Prevention Among Students of Federal College of Education, Kontagora, Niger StateDocument5 pagesKnowledge of HIV/AIDS and The Use of Contraceptives (Condom) As Prevention Among Students of Federal College of Education, Kontagora, Niger StateIka Yuni WulandariNo ratings yet

- Uh 0117446Document8 pagesUh 0117446Demna BenusaNo ratings yet

- 5.0 Summary, co-WPS OfficeDocument5 pages5.0 Summary, co-WPS OfficeJames olaoluwa100% (1)

- Evaluating HIV/AIDS Knowledge and Awareness Dynamics: Insights From Adult Populations in IndiaDocument5 pagesEvaluating HIV/AIDS Knowledge and Awareness Dynamics: Insights From Adult Populations in IndiaInternational Journal of Innovative Science and Research TechnologyNo ratings yet

- Melinda PechaycoDocument30 pagesMelinda PechaycoChristian Paul ChuaNo ratings yet

- Public Health - Vol 2 - Issue 4 - Article 5Document44 pagesPublic Health - Vol 2 - Issue 4 - Article 5kaisamerno2003No ratings yet

- Review Socio Economical 1475-9276!13!18Document22 pagesReview Socio Economical 1475-9276!13!18saadNo ratings yet

- Hssp-Iii PlanDocument15 pagesHssp-Iii PlanVishesh JainNo ratings yet

- Chapter 2Document6 pagesChapter 2Nica Jane MacapinigNo ratings yet

- Morales ResearchDocument17 pagesMorales ResearchLanelyn TabigueNo ratings yet

- ProjectDocument20 pagesProjectakinmusiregNo ratings yet

- I Am (Un) Safe: Implementation of Educational Pamphlet and Online Campaign (EPOC) To Increase The Level of Awareness On Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) of Grade 11 StudentsDocument6 pagesI Am (Un) Safe: Implementation of Educational Pamphlet and Online Campaign (EPOC) To Increase The Level of Awareness On Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) of Grade 11 StudentsPsychology and Education: A Multidisciplinary JournalNo ratings yet

- Ni JGDocument7 pagesNi JGTessa Audy JaniarNo ratings yet

- Evaluate The Existing Integration of Sexual Reproductive Health Services With 9055Document11 pagesEvaluate The Existing Integration of Sexual Reproductive Health Services With 9055Rose Mmusi-PhetoeNo ratings yet

- Penggunaan Kondom ThailandDocument12 pagesPenggunaan Kondom ThailandIrma PayukNo ratings yet

- Overview of HIV Interventions For Young PeopleDocument8 pagesOverview of HIV Interventions For Young PeopleCrowdOutAIDSNo ratings yet

- AIDS & Clinical Research: Journal ofDocument7 pagesAIDS & Clinical Research: Journal ofzakiNo ratings yet

- Name: Ayanna Spence Grade: 11U Teacher: MR Haughton Subject: Biology Date: September 13, 2019Document18 pagesName: Ayanna Spence Grade: 11U Teacher: MR Haughton Subject: Biology Date: September 13, 2019skeetsamNo ratings yet

- IDSA and CPE CertificateDocument3 pagesIDSA and CPE CertificateMuniba NasimNo ratings yet

- Balochistan WorldBankDocument223 pagesBalochistan WorldBanknageshbhushan9773No ratings yet

- EE - UNCOMPRESSED PDF - Part 3 NotesDocument127 pagesEE - UNCOMPRESSED PDF - Part 3 NotesAbhinav TripathiNo ratings yet

- Obs and Gynae PassmedDocument7 pagesObs and Gynae PassmedrahulNo ratings yet

- Topic - Version Subject - ObgDocument23 pagesTopic - Version Subject - ObgMandeep Kaur100% (1)

- Acute Myocardial Infarctation-7Document249 pagesAcute Myocardial Infarctation-7Sonia Carolina Camacho SandovalNo ratings yet

- Quality Mental Health Research in The PhilippinesDocument102 pagesQuality Mental Health Research in The PhilippinesclintonducayNo ratings yet

- Madeline Maddy Meiser Updated ResumeDocument2 pagesMadeline Maddy Meiser Updated Resumeapi-741387543No ratings yet

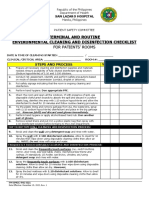

- Fm-Omcc-Psc-021 Terminal and Routine Environmental Cleaning and Disinfection Checklist.Document2 pagesFm-Omcc-Psc-021 Terminal and Routine Environmental Cleaning and Disinfection Checklist.Sheick MunkNo ratings yet

- SEXH - Infertility (2p)Document2 pagesSEXH - Infertility (2p)Omar HamwiNo ratings yet

- NYS Gov. Andrew Cuomo May 15 Coronavirus PresentationDocument48 pagesNYS Gov. Andrew Cuomo May 15 Coronavirus PresentationZachary WilliamsNo ratings yet

- Gastroenteritis in AdultsDocument6 pagesGastroenteritis in Adultsaufa ahdiNo ratings yet

- GFPI-F-019 - Guia - de - Aprendizaje Ingles 10Document7 pagesGFPI-F-019 - Guia - de - Aprendizaje Ingles 10ELIANA ALEJANDRA MORENO CARDOZONo ratings yet

- Khetri-Mandawa Town Notes JhunjhunuDocument2 pagesKhetri-Mandawa Town Notes JhunjhunuNarendra AjmeraNo ratings yet

- CD QuizDocument8 pagesCD QuizfilescrocsNo ratings yet

- NR 602 Week 8 Final Exam Completed Study GuideDocument20 pagesNR 602 Week 8 Final Exam Completed Study GuideTyler HemsworthNo ratings yet

- Reproductive and Child Health ProgrammeDocument37 pagesReproductive and Child Health ProgrammeVeena JV100% (3)

- Breast Feeding LogDocument2 pagesBreast Feeding Logaihpark100% (1)