Neuropalliative Care

Neuropalliative Care

Uploaded by

Thales Michel Santos PaixãoCopyright:

Available Formats

Neuropalliative Care

Neuropalliative Care

Uploaded by

Thales Michel Santos PaixãoOriginal Title

Copyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Neuropalliative Care

Neuropalliative Care

Uploaded by

Thales Michel Santos PaixãoCopyright:

Available Formats

VIEWS & REVIEWS

Neuropalliative care

Priorities to move the field forward

Claire J. Creutzfeldt, MD, Benzi Kluger, MD, Adam G. Kelly, MD, Monica Lemmon, MD, David Y. Hwang, MD, Correspondence

Nicholas B. Galifianakis, MD, Alan Carver, MD, Maya Katz, MD, J. Randall Curtis, MD, Dr. Creutzfeldt

and Robert G. Holloway, MD clairejc@uw.edu

®

Neurology 2018;91:217-226. doi:10.1212/WNL.0000000000005916

Abstract RELATED ARTICLE

Neuropalliative care is an emerging subspecialty in neurology and palliative care. On April 26, Editorial

2017, we convened a Neuropalliative Care Summit with national and international experts in Palliative care needs are

the field to develop a clinical, educational, and research agenda to move the field forward. everywhere: Where do we

begin?

Clinical priorities included the need to develop and implement effective models to integrate

palliative care into neurology and to develop and implement informative quality measures to Page 201

evaluate and compare palliative approaches. Educational priorities included the need to im-

prove the messaging of palliative care and to create standards for palliative care education for

neurologists and neurology education for palliative specialists. Research priorities included the

need to improve the evidence base across the entire research spectrum from early-stage

interventional research to implementation science. Highest priority areas include focusing on

outcomes important to patients and families, developing serious conversation triggers, and

developing novel approaches to patient and family engagement, including improvements to

decision quality. As we continue to make remarkable advances in the prevention, diagnosis, and

treatment of neurologic illness, neurologists will face an increasing need to guide and support

patients and families through complex choices involving immense uncertainty and intensely

important outcomes of mind and body. This article outlines opportunities to improve the

quality of care for all patients with neurologic illness and their families through a broad range of

clinical, educational, and investigative efforts that include complex symptom management,

communication skills, and models of care.

Introduction

The past few decades have seen remarkable progress in lessening the burden of neurologic disease,

for example by reducing the number of relapses and delaying disability in multiple sclerosis,1 by

reducing symptoms and prolonging independence in Parkinson disease,2 and by preventing and

even reversing certain types of stroke.3,4 Despite this progress, 1 billion people across the globe

have a neurologic illness, and more than 1 in 10 deaths are caused by neurologic disease.5

Moreover, most neurologic diseases remain incurable, shorten a person’s lifespan, reduce time to

dependence, diminish quality of life, and are associated with pain and other physical, psychological,

and spiritual sources of suffering that are often difficult to control.

Palliative care is an approach to medical care for patients with serious illness that focuses on

pain and symptom management, psychosocial and spiritual support, and effective communi-

cation to improve the quality of life of patients and their families and caregivers. Palliative care

has seen a remarkable growth in the past decade, and the majority of US hospitals now have

palliative care services.6 In addition, evidence continues to accumulate suggesting a benefit of

From the Department of Neurology (C.J.C.), University of Washington, Harborview Medical Center, Seattle; Department of Neurology (B.K.), University of Colorado Anschutz Medical

Center, Denver; Department of Neurology (A.G.K., R.G.H.), University of Rochester Medical Center, NY; Department of Pediatrics (M.L.), Division of Child Neurology, Duke University

Hospital, Durham, NC; Division of Neurocritical Care and Emergency Neurology (D.Y.H.) and Center for Neuroepidemiology and Clinical Neurological Research (D.Y.H.), Yale School

of Medicine, New Haven, CT; Department of Neurology (N.B.G., M.K.), University of California in San Francisco; Department of Neurology (A.C.), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer

Center, New York, NY; and Cambia Palliative Care Center of Excellence (J.R.C.), University of Washington, Seattle.

Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures. Funding information and disclosures deemed relevant by the authors, if any, are provided at the end of the article.

Copyright © 2018 American Academy of Neurology 217

Copyright ª 2018 American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Glossary

AAHPM = American Academy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine; AAN = American Academy of Neurology; ABPN =

American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology; ACGME = Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; EHR =

electronic health record; ICD-10 = International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Revision.

palliative care for various kinds of diseases including cancer meetings were followed by a plenary session during which

and heart disease,7 and several neurologic illnesses.8–10 a representative from each group presented the groups’

deliberations and incorporated feedback from all participants.

The “palliative care approach” describes the type of care the This report presents a summary of the strategic priorities

patient and family receive rather than the type of clinician developed for neuropalliative care organized into the 3 cate-

providing this care. Therefore, it encompasses both primary gories of (1) clinical practice, (2) education, and (3) research.

palliative care (provided by the patients’ primary medical team, An executive summary of these priorities is shown in table 2.

including neurologic care) and specialist palliative care (pro-

vided by clinicians with subspecialty training in palliative

care).11 Within this framework, we define a “neuropalliative Results

care approach” as care that focuses on the specific needs of

patients with neurologic illness and their families, including Clinical practice

both primary and specialist palliative care. Neuropalliative care The following priorities were identified in the clinical practice

thus encompasses both an emerging subspecialty within neu- breakout group: (1) develop and implement effective models to

rology and a holistic approach to people who have neurologic integrate palliative care into neurology in- and outpatient care;

illnesses that require a unique skill set, as suggested in table 1. (2) develop and implement informative quality measures to

evaluate and compare palliative approaches to each other and

The importance of palliative care for neurologic disease is in- to standard care; (3) better align financial and other incentives to

creasingly recognized, and we are seeing a growing number of promote patient-centered care; and (4) improve access to hos-

educational initiatives and practice guidelines12–15 that address pice care and update hospice criteria for neurologic disorders.

palliative care within different neurology specialties. However,

most such undertakings rely on a small evidence base. Now is Develop and implement effective models of

integrating palliative care into neurology

the time to ask the question: “What are the top priorities for

The Institute of Medicine recommends that all people with

improving the outcomes of patients with serious neurologic

serious illness have access to skilled palliative care,16 and this

illness and their families through a palliative care approach?”

recommendation is endorsed by the AAN,17 the American

Stroke Association,12 American Heart Association,18 and the

To address this question and to set an agenda to develop the

Neurocritical Care Society.13 Skilled palliative care includes

evidence needed to improve the quality of care that we pro-

both primary palliative care skills (including timely identifi-

vide these patients, we convened a group of neurology and

cation of palliative care needs and basic management of pain

palliative care experts during the 2017 American Academy of

and other symptoms, as well as discussions around prognosis,

Neurology (AAN) meeting. The goal of this meeting was to

goals of care, code status, and suffering) and specialist palli-

develop a focused set of clinical, research, and educational

ative care (including management of more complex physical,

priorities to move the field of neuropalliative care forward.

psychosocial, and spiritual suffering, conflict resolution re-

garding goals or treatment options, or assistance in addressing

cases of potentially inappropriate care).11,19

Methods

Participants were national and international experts in the Evidence on how best to integrate palliative care into neu-

fields of neurology and palliative care (listed in the acknowl- rology is limited. Several models exist, both in the inpatient

edgment section). Invitations were sent out to neurologists (and critical care)20,21 and in the outpatient setting,9,22–25 and

and trainees with known interest in the field, including those include:

who were on a neuropalliative care listserve. The meeting, the

“Neuropalliative Care Summit,” was held for one half day A. A consultative model where palliative care specialists are

during the AAN meeting on April 26, 2017. Given this venue, consulted—the traditional “neurologic” treatment stays

the majority of participants were physicians, with only a mi- within the neurologists’ practice and patients are referred

nority of representatives from other clinician groups such as to see a palliative care specialist separately.

social work, spiritual care, or nursing and no patient repre- B. An integrated model where a palliative care approach is

sentatives. Meeting participants formed breakout groups fo- shared simultaneously across primary providers and specialty

cused on developing a clinical, educational, and research teams. In the outpatient setting, this model may be realized

agenda for improving palliative care in neurology. Group through a multidisciplinary clinic where neurologists,

218 Neurology | Volume 91, Number 5 | July 31, 2018 Neurology.org/N

Copyright ª 2018 American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Table 1 Suggested core palliative care skills for neurologists

(a) Identify common palliative care needs associated with specific neurologic disorders

(b) Detect and manage whole body pain

(c) Provide basic psychosocial and spiritual support

(d) Acquire communication skills including empathetic listening

(e) Effectively estimate and communicate prognosis and uncertainty

(f) Master shared decision-making for common preference sensitive decisions

(g) Master shared decision-making and support for patients and families around tragic choices

(h) Be aware of palliative care options of last resort

(i) Recognize and manage caregiver distress and needs

palliative or neuropalliative care specialists, and an in- Some palliative care–oriented quality measures already exist in

terdisciplinary team cohabitate a clinic space.26,27 In the the neurology literature. These include screening measures

inpatient setting, palliative or neuropalliative care specialists around the domains of symptom management and advance

would join discussions on rounds and family meetings are care planning for certain diseases (for example, amyotrophic

held with both neurology and palliative care teams together. lateral sclerosis,33 dementia,34 Parkinson disease,35 and in-

C. A primary neuropalliative care model involving palliative patient and emergency neurology36). As we recognize the need

care education and training for neurologists to provide for a high-quality neuropalliative care approach to all patients

neuropalliative care themselves. In the outpatient setting, with serious neurologic illness, additional domains need to be

this might also include training nonneurologists (e.g., considered. For example, the recently published palliative and

primary care providers, geriatricians) who take care of end-of-life measure set by the National Quality Forum37

patients with neurologic disease. includes measures within the following domains: comfortable

dying, symptom screening, beliefs and documentation of val-

These models are not mutually exclusive, and optimal cov- ues, care preferences, and treatment preferences. Such meas-

erage of palliative care needs for neurology will involve ures can be incorporated into innovative quality-improvement

a combination of these approaches. Different models will also programs that can benchmark quality of care and build tools

be needed for different settings. For example, academic such as reminder alerts and care documentation requirements

institutions with around-the-clock availability of consultants within the electronic health record (EHR).38,39 As an example,

will need different models than community practices. Rural if the goal is to ensure that patients’ and families’ social and

and other relatively underserved areas may benefit from tel- spiritual support needs are met, a quality-improvement pro-

ehealth and tele-education models to increase access to pal- gram would involve developing a tool to help clinicians assess

liative care or neuropalliative care specialists.28 for relevant needs, educating clinicians in appropriate com-

munication skills and other skills to meet those needs (either

All of these approaches require that neurologists have basic themselves or through appropriate use of other resources,

palliative care skills, that palliative care specialists learn basic such as chaplaincy), developing policies to ensure these

tenets of neurology, and that we encourage the development conversations are taking place with the appropriate clinicians

of triage systems for specialist palliative care consultations, and within an appropriate time frame, and designing tools

both in the inpatient and outpatient setting.11,16,29 within the EHR to document and communicate that process.

When possible, these measures should also be compatible

Develop and implement quality measures to improve with other national efforts for data-tracking in palliative care,

practice such as Measuring What Matters from the American Acad-

Considerable variation exists in life-sustaining and end-of-life emy of Hospice and Palliative Medicine (AAHPM),40 the

care practices for patients with neurologic diseases. This Quality Data Collection Tool for Palliative Care,45 or Palli-

variation results from differences in patients and surrogate ative Care Quality Network.41

preferences, as well as differences in how well clinicians

practice shared decision-making, including communication Better align financial and other incentives to promote

about prognosis and eliciting preferences. Given recent data patient-centered care

showing dramatic variations in hospital-level rates of “comfort Palliative care is by nature interdisciplinary and includes social

measures only” (CMO) orders in patients with stroke, and work, spiritual care, nursing, and advanced nursing practice.

limited documentation of patient preferences for life-limiting The services provided by many of these clinicians are not

therapies in the medical record, considerable quality im- reimbursed by insurance and instead tend to be funded

provement opportunities exist.30–32 through other means and justified through (1) the

Neurology.org/N Neurology | Volume 91, Number 5 | July 31, 2018 219

Copyright ª 2018 American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

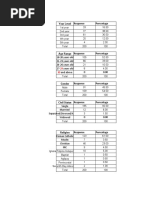

Table 2 Neuropalliative care: Executive summary of strategic priorities

Clinical

To develop effective models to integrate palliative care into neurology, including consultative models, primary palliative care models, and an integrated

comanagement approach to care. This will include the development of tele-medicine approaches to improve access to palliative care services for those

who have barriers to receiving such care based on geography or disability.

To develop and implement specific quality measures that can be tracked and quantified across providers and sites of care. These include domains such as

quality of dying, symptom screening, documentation values and goals of care, and care preferences.37 Combining patient-reported data with important

palliative care components such as periodic serious illness conversations will help evaluate these components and their effect on patient outcomes.

To better align incentives to promote patient-centered care by advocating for payment reform and use of appropriate evaluation and management codes

that recognize advance care planning, palliative care, and coordination of care.

To improve access to hospice care and update hospice criteria for neurologic disorders.

Education

To reduce the stigma of palliative care and to help clinicians, patients, families, and other stakeholders understand the advantages of timely palliative care

to promote informed choices and improve quality of life.

To improve palliative care education for neurologists, including standardizing a core palliative care skill set and palliative care experience that all neurology

trainees should master, as well as more specialized training specific to certain diseases and needs.

To improve access to neuropalliative care education for all providers. For neurologists and trainees, this includes (neuro-)palliative care fellowships,

graduate courses in palliative care, and specific (neuro-)palliative care and communication workshops. More neuro-specific educational tools need to be

available to palliative medicine specialists and other clinicians.

To incorporate education and testing within official training programs—including the ABPN, HPM, and ACGME—will be an important step in motivating

implementation of an educational standard in neuropalliative care.

Research

To better understand the natural history of neurologic disease, not only as it relates to mortality but also as it relates to outcomes considered most

important to patients and to their families. This goal includes investigating the processes leading to these outcomes, such as communication and

treatment decisions and the delivery of “goal-concordant care.”

To develop methods to help identify the needs of an individual patient, family, and situation and prompt certain conversations (including goals of care

discussions), specialist consultations, or hospice referral. This includes improving the tools to prognosticate neurologic illness and communicate the

information to loved ones and decision-makers.

To develop better interventions (e.g., drugs, devices, service delivery strategies, and behavioral interventions) to meet the needs of our patients and their

families, to manage distressing symptoms, and to improve care while reducing unwanted burden and costs.

To better understand how people make decisions—especially how they partner with clinicians in making those decisions (shared decision-making), what

decisional support they need, and how cognitive biases (e.g., the disability paradox, adaptation, framing), emotions, or prognostic uncertainty influence

decision-making—and to develop additional tools and decision aids to embed into the clinical work flows to facilitate decision-making.

To find optimal ways of integrating palliative care into the care of patients with neurologic illness and their families across academic and community

settings and to educate neurologists, trainees, and other clinicians about neuropalliative care.

Abbreviations: ABPN = American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology; ACGME = Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; HPM = Hospice and

Palliative Medicine.

importance of health care innovation and improved quality of insurance billing purposes is important. This includes using

care, and (2) the cost savings incurred by reducing the utili- Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) billing modifiers for

zation and intensity of health care. Managed care organ- prolonged service (e.g., 99354) or advance care planning

izations, such as Veterans Affairs Medical Centers, or (99497 or 99498).42 In addition to using the ICD-10 code for

government-run health systems, such as the UK National the primary neurologic disease that a patient has, adding an

Health Services have been early adopters of palliative ICD-10 code for palliative care encounter (Z51.5, was V66.7

care—in part because the cost savings to the system, in ad- in ICD-9) is important to better track these visits. More can

dition to improvement in quality of care, can justify the costs be done, however, by federal and state agencies, payers, and

of staffing. In fee-for-service models, financial support is more health systems to develop better reimbursement policies that

challenging and requires institutional support, research promote patient-centered care.

grants, and philanthropy. Without such support, it is difficult

for neurologists to meet their clinical billing requirements In addition to financial incentives, it is also important to align

through palliative care visits, given that insurance re- other types of incentives to facilitate integration of palliative

imbursement will not adequately cover the time spent with care into care for patients with neurologic disorders. For ex-

patients during these more time-intensive appointments. ample, having clinical leadership prioritize palliative care in

Understanding how to optimally code clinic visits for clinical services and education will advance the uptake of high-

220 Neurology | Volume 91, Number 5 | July 31, 2018 Neurology.org/N

Copyright ª 2018 American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

quality palliative care. Acknowledging success in meeting Step,” or “Complex Symptom Management” clinics in the hopes

palliative care needs for patients and families can highlight the that these terms may be culturally more acceptable.

importance of this care.

Creating a primary palliative care education

Improve access to hospice care and update hospice curriculum for neurologists

criteria for neurologic disorders All neurologists, including residents and physicians in practice,

Summit participants raised several issues concerning hospice should be able to provide primary palliative care to patients

care for patients with neurologic illnesses. First, criteria for with serious neurologic illness48 (table 1). Specialized training

hospice eligibility are well developed for cancer patients but is needed for neurologists focusing on neuropalliative care to

tend to be less appropriate or absent for chronic neurode- gain command of more advanced palliative care skills and

generative diseases.43 Evidence-based hospice criteria for knowledge. Some neurologists may require training focused

neurologic illnesses are needed. Second, participants raised on the palliative care needs of their subspecialty populations

concerns that hospice systems and providers may be less (for example, movement disorders, neuro-oncology) or spe-

comfortable accepting patients with neurologic diagnoses and cialized settings (for example, intensive care units, outpatient

may benefit from neurology-specific training and materials, clinics, or hospice), whereas others may be broadly interested

such as education about storming after severe acute brain in neuropalliative care as its own specialty encompassing

injury or the inclusion of a Parkinson disease–specific hospice multiple diseases and settings. These approaches all have their

kit that does not include haloperidol. Finally, hospice stand- own merits and each suggest different needs in terms of ed-

ards vary regionally, and there may be a need for modifications ucational paths and materials.

based on local and regional regulations and resources.

Primary neuropalliative care education should parallel estab-

Education lished practices in palliative care education using examples

The priorities identified in the education breakout group were from neurologic illnesses and emphasizing unique aspects of

to (1) reduce the stigma of palliative care; (2) create standards neurologic disease. Educational efforts should be guided by

for primary palliative care education for neurologists; (3) empiric needs assessments of target audiences to determine

increase access to neuropalliative care education for all pro- current perceptions (and misperceptions), knowledge gaps,

viders; and (4) incorporate palliative care education and attitudes, and self-perceived needs. Other skills may be

testing within residency and fellowship training programs. needed by clinicians working in this field, which are not

specific to palliative care but are needed for effective care, such

Reducing the stigma of palliative care as working in teams and preventing burnout.49

Given the historical development of palliative care from end-

of-life care, summit participants raised concern that there may Access to neuropalliative care education

be a misconception among clinicians and patients that palli- Neurologists and neurology providers

ative care is equivalent to end-of-life care and that its in- The American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN)

troduction indicates imminent death. Clinicians may view recognized Hospice and Palliative Medicine as a subspecialty

death and decline as a medical failure instead of embracing the with a qualifying examination in 2006. Since 2012, a 12-month

inevitable as an expected and natural outcome. Similarly, Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education

clinicians and patients may perceive palliative care as an ap- (ACGME) fellowship is required to become board-eligible in

proach when there is “nothing left to do,” when in fact an Hospice and Palliative Medicine. In 2017, there were 130

aggressive palliative care approach requires expertise, crea- accredited fellowships available in the United States. In the same

tivity, and a commitment to reduce suffering and improve the year, the ABPN Credentials Department counted 53 “diplomates

quality of life and the quality of dying.44 in the subspecialty of Hospice and Palliative Medicine,” among

an overall 14,268 neurologists with active certificates (personal

Neurologists frequently shy away from discussing the “p” (for communication with ABPN and ABPN.com). This discrepancy

palliative) or “h” (for hospice) words with patients because they highlights the shortage of neuropalliative care specialists.

are afraid to diminish patients’ hopes. The literature suggests that

the contrary is true: that timely conversations about goals of care Midcareer neurology clinicians have a variety of options to

begun before the final weeks of life do not increase depression, build their palliative care skills. These include comprehensive

can improve quality of life, and are associated with a better palliative care courses (e.g., the University of Washington

alignment of care with patients’ preferences.7,45 The cultural Graduate Certificate Course in Palliative Care); master pro-

stigma surrounding palliative care limits its accessibility.46,47 grams in palliative care offered by some graduate schools (e.g.,

Some argue that continued palliative care education, mentor- University of Colorado); courses for building palliative care

ship, and leadership in medical school, residency, and fellowship leadership (e.g., the Harvard Medical School Palliative Care

settings will be the most effective way to shift the perception of Education and Practice course); online educational materials

palliative care among medical providers, while others recom- and training modules as offered by the Education in Palliative

mend “rebranding” a new term. Some neuropalliative care clinics and End-of-Life Care program (epec.net); and courses and

have chosen to name their clinics “Supportive Care,” “Next workshops that focus on specific skills, such as

Neurology.org/N Neurology | Volume 91, Number 5 | July 31, 2018 221

Copyright ª 2018 American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

communication (e.g., VitalTalk). Other opportunities for requirements (e.g., quality metrics) will be an important step in

palliative care education and certification for physicians and motivating implementation. Also discussed was whether a re-

other health care providers can be found through the Center quirement for direct palliative medicine exposure (e.g., a certain

to Advance Palliative Care.6 number of weeks on a palliative care service) should be re-

quired for all neurology residents. Lastly, our ongoing neuro-

The AAN and other neurology subspecialty societies are in- palliative care working group is open to interested members

creasingly offering palliative care courses during their annual and aims to coordinate efforts for the creation and dissemi-

meetings. Partnerships with other clinical organizations (e.g., nation of materials and to reduce redundant efforts.

National Association of Social Workers) and patient advocacy

groups (e.g., Alzheimer’s Association, ALS Association, etc.) To disseminate these efforts, buy-in will be required from

should be pursued to develop materials appropriate for other residency program directors and national boards (e.g., ABPN,

disease-specific populations. Hospice and Palliative Medicine, ACGME). Research is ur-

gently needed to define current training gaps and inform the

Finally, with a growing interest for more formal training in development of relevant competencies.

neuropalliative care, there is momentum for building dedi-

cated neuropalliative care fellowships or creating specialized Research agenda

neurology tracks within existing fellowships (e.g., University The research working group identified urgent priorities within

of Colorado starting in 2018). the following areas: (1) Epidemiology and Outcomes; (2)

Needs Assessments; (3) Interventions (pharmacologic,

Palliative medicine specialists technology, and behavioral); (4) Patient and Family En-

Palliative medicine specialists who interact with patients and gagement; and (5) Implementation and Dissemination. The

families affected by neurologic disease—be it in inpatient, agenda below focuses on what needs to be investigated

outpatient, or hospice settings—need to understand basic without prescribing how these investigations should be pur-

principles of care specific to neurologic disease, including the sued. Advancing this agenda will require the incorporation of

unique aspects around prognosis, prognostic uncertainty, and complementary research methodologies, including qualitative

the effect of cognitive biases.50 They, too, may benefit from research, mixed methods, health services research, and

additional training, as described above. FAST FACTS is an- implementation science. Unique data sources, inclusive of

other online resource that was founded and is edited by fac- both large datasets (e.g., registries or claims data) and quali-

ulty at the Medical College of Wisconsin and currently has tative sources (e.g., interviews or focus groups), will add rigor

more than 300 “facts” on palliative care issues relevant to and depth. Identifying training opportunities and facilitating

a variety of illnesses (pcnow.org). There are currently few pathways for those interested and motivated in learning var-

neurology entries and new submissions can be easily uploaded ious methodologic approaches should be priorities for our

and approved. Other potential avenues to increase reach neuropalliative care community.

within the palliative medicine community include creating

a special interest group for neurology at the AAHPM and Epidemiology and outcomes research

creation of neurology training modules for the National To ensure the delivery of high-quality neuropalliative care, we

Hospice and Palliative Care Organization. need to better understand the natural history of neurologic

disease, not only as it relates to mortality but also as it relates

Other professionals to outcomes considered most important to patients and to

Those who interact with patients with neurologic illnesses their families, including quality of life, spiritual and psycho-

and/or their families include geriatricians, social workers, logical well-being, social reintegration, and quality of death. In

chaplains, physical therapists, speech language pathologists, addition, we must understand the processes leading to these

pharmacists, and nurses. Resources for Palliative Care Edu- outcomes, including communication and treatment decisions

cation can be found through the Center to Advance Palliative and the delivery of “goal-concordant care”—a term in-

Care (capc.org). Palliative care certification and credentialing creasingly used to express the aim of ensuring “that care

are found through professional websites (for example, the provided matches closely with each individual’s goals.”51–53

North American Social Work Credentialing Center and the This aspect is of particular importance in neurologic disease

Hospice and Palliative Credentialing Center for nurses). where (1) patients are often unable to express their goals

themselves once they are sick, and (2) where a future health

Incorporate education and testing within official state, including the ability to adapt to it, can be extremely hard

training programs to predict or imagine (“affective forecasting”). Domains im-

Minimal competencies should be set for each clinician group to portant for public health include measures of costs or burden

standardize education across settings and to guide the creation of treatment, health care utilization, and access to care.

of test questions for boards and in-service training examina-

tions; for example, for neurologists to know hospice guidelines Of the variety of different outcomes important in neuropalliative

and how to refer patients to hospice. Adding palliative care care, some may require novel measures to be developed while

material to neurology board examinations and other others may be assessed with existing validated tools.

222 Neurology | Volume 91, Number 5 | July 31, 2018 Neurology.org/N

Copyright ª 2018 American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

1. Patient outcomes: For patients with certain neurologic or other symptoms, concerns about prognosis or

disorders, assessments of cognitive and psychological treatment, and clarity of goals of care. Studying this

outcomes are of particular importance, as opposed to and/or related instruments may help identify the optimal

a traditional focus on purely functional outcomes.54 settings for implementation.

Because many patients with severe neurologic disease 2. Serious illness conversation triggers are objective signs

may be nonverbal, or unable to understand the and symptoms that can prompt providers to initiate or

measurement tool, assessments of patient outcomes readdress conversations about goals of care, patient

may require or rely on the input from proxies (family values, or end of life. More research is needed regarding

members or caretakers) and therefore need to be how best to identify the appropriate time to approach

validated for proxy assessment. In addition, visual scales goals-of-care situations for patients with diseases that

and other nonverbal alternatives should be further have unpredictable natural histories.

evaluated. 3. Estimating prognosis: A patient’s prognosis guides

2. Family and caregiver outcomes: Family and surrogates of communication and decision-making. Discussion re-

patients with neurologic illness are at high risk of poor garding the need for research in neuroprognostication

health outcomes of their own, such as poorer overall self- centered on understanding the proper role of using

rated health and increased rates of depression.55 The population-based outcomes data and clinical scales in

difficulty caregivers face when their loved one is affected determining prognosis for individual patients. Many of

by a neurologic disease, especially those that affect the existing scales predict relatively crude measures of

cognition, presents unique challenges. functional outcome, without an emphasis on outcomes

3. Decision outcomes: One main focus of palliative care is that may be relevant to individual patient or family

to improve patient-centered treatment decisions through quality of life. Clinical scales and outcome prognostica-

improved communication and patient engagement. tion tools that specifically address cognitive outcomes

Better tools are needed to rate the process of decision- and other outcomes relevant to patient and family/

making and the quality and aspects of a decision, to better caregiver quality of life are needed.

attain goal-concordant care (also see the patient 4. Hospice eligibility criteria: As discussed above (in the

engagement innovations section below). section “improve access to hospice care and update

4. Public health outcomes: Measuring health care costs and hospice criteria for neurologic disorders”), criteria for

health care utilization can assist us in uncovering factors hospice eligibility are well developed for patients with

that contribute to disproportionate costs and potentially cancer but tend to be less applicable for severe acute brain

unwanted treatments, especially at the end of life. In diseases or for chronic neurodegenerative disease.43

addition, we need to better understand the variability in Logical hospice criteria need to be developed that focus

treatment decisions across hospitals, geographic regions, not only on the amount of time left for the patient but on

or racial groups, and consider interventions to reduce their specific needs.

unexplained variance.56 Research on health care dispar-

ities is needed as it relates to detecting disparities in Intervention research

access to and delivery of neuropalliative care, under- To better meet the needs of our patients and their families, we

standing the factors that underlie them, and intervening need to investigate the use of drugs, devices, and behavioral

to eliminate them.57 interventions. One particularly challenging area of research is

end-of-life care, where evidence-based medicine is almost

Needs assessments entirely absent.

Palliative care needs range from pain and physical distress to

psychological and existential suffering. Patients and families 1. Drugs: Heightened awareness of the excessive use of

with palliative care needs are more likely to have poor out- opioids in this country emphasizes the importance of

comes and may benefit from certain neuropalliative care therapeutic trials for improved pain and symptom

interventions. A variety of proposed methods to identify control, including in advanced or terminal illness. At

patients or needs were reviewed, which can facilitate primary the same time, efforts to address the opioid epidemic

or specialist palliative care in a timely manner. should not interfere with appropriate use of opioids,

especially for patients with terminal illness and pain

1. Palliative care needs checklists can help target care to the requiring opioids.59 Medications for other disabling

needs of an individual patient, family, and situation and symptoms, ranging from agitation to fatigue, are also

prompt certain conversations or specialist consultations. needed.

They can help identify patients or families at high risk of 2. Devices and technology: The role of information

psychological morbidity or those receiving care discor- technology in hospice and palliative care is gaining

dant to their values. One example from the neuro-ICU is enthusiasm and includes projects such as telecommuni-

the SuPPOrTT checklist,58 in which clinicians screen for cation for home hospice patients and caregivers, such as

unmet needs during daily rounds by asking several simple “virtual visits,” web-based conferences, worksheets and

questions regarding the presence of support needs, pain expert feedback, or specific use of the EHR, including

Neurology.org/N Neurology | Volume 91, Number 5 | July 31, 2018 223

Copyright ª 2018 American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

triggers to consult a specialist or prompts for a serious routine health care.61 Improving palliative care for patients with

illness conversation. The use of mobile technology to serious neurologic illness will require research not just to dem-

better collect real-time patient-level information is being onstrate efficacy and effectiveness of interventions but also to

tested in a variety of other clinical and research settings; efficiently implement and disseminate interventions that pro-

translation of this approach to the neuropalliative care mote effective, high-quality palliative care across evolving health

field should be investigated. systems. This will require in-depth knowledge of best practice

3. Behavioral interventions need to be explored across and the science of implementation and organizational change,

a broad range of disorders and settings, evaluating the including input from diverse stakeholders. Evaluation of clinical

effect of communication interventions (e.g., teaching and educational efforts and models of palliative care delivery is

communication skills to clinicians, promoting advance needed as outlined above. As in all other areas of medicine, tele-

care planning); support interventions (e.g., pairing patients health (tele-consultations, videoconferences, e-learning ini-

or families with a specially trained support nurse, bringing tiatives, and remote monitoring) is a promising way of getting

a chaplain to a clinic visit); or psychological interventions high-quality subspecialty care to smaller, remote hospitals and

(e.g., providing patients or families with coping skills, clinics and even to patients’ homes. Research is needed to

teaching emotional resilience to clinicians). identify ways to integrate these technological advances into

medical care including how to reimburse for them.

Patient/family engagement

Patients with neurologic illness, their families, and their clini-

cians face multiple complex decisions over the course of the Conclusion

illness and at the end of life. Many patients lose decision- Neuropalliative care is an emerging field with a bright future.

making capacity and their family members become their sur- As we continue to make remarkable advances in diagnosis and

rogate decision-makers. There was consensus that research is treatment, there will be an increasing need to guide patients

needed to better understand how people make decisions— and families with neurologic disease through complex choices

especially how they partner with clinicians in making those involving immense uncertainty and intensely important out-

decisions (shared decision-making), what decisional support comes of mind and body. We need to confront these chal-

they need, and how cognitive biases (e.g., the disability para- lenges head-on and develop and execute plans to address the

dox, adaptation, framing), emotions, or prognostic uncertainty priorities within this nascent field. Only then will we deliver

influence decision-making.50 Aspects of decision-making that on our promise to patients and families to provide optimal

were discussed included the following: care, a palliative care approach to care, from diagnosis to those

final moments of lives well lived.

1. Communicating prognosis: Research on the best

practices for disclosing uncertain or poor neurologic

prognosis to patients and families is a clear area of need. Author contributions

Given the prevalence of prognostic uncertainty in Dr. Creutzfeldt: study concept and design, acquisition of

neurology, frameworks to discuss uncertainty are high data, analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the

priority. Of particular relevance to neuropalliative care is manuscript for important intellectual content, study super-

understanding best approaches to communicating with vision. Dr. Kluger: study concept and design, acquisition of

surrogate decision-makers. Prior research has shown that data, analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the

patient-surrogate agreement is lower for neurologic manuscript for important intellectual content, study super-

disorders than for medical conditions.60 vision. Dr. Kelly: acquisition of data, analysis and in-

2. Advance care planning and serious illness communica- terpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important

tion: Research is needed to better evaluate the advance intellectual content. Dr. Lemmon: acquisition of data,

care planning process in patients with neurologic analysis and interpretation, critical revision of the manu-

disorders. Specific goals may include assessing the rate script for important intellectual content. Dr. Hwang:

that neurology patients participate in advance care acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, critical re-

planning, how and when planning should be updated as vision of the manuscript for important intellectual content.

disorders evolve, and whether advance planning is Dr. Galifianakis: acquisition of data, analysis and in-

associated with more goal-concordant care. terpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important

3. Decision aids: Novel decision aids need to be developed intellectual content. Dr. Carver: acquisition of data, analysis

for common goals-of-care situations in clinical neurosci- and interpretation. Dr. Katz: acquisition of data, analysis and

ence to better elicit preferences and more informed interpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for im-

choices. These tools will need to be developed with clear portant intellectual content. Dr. Curtis: analysis and in-

triggers for use and applicability across different cultures. terpretation, critical revision of the manuscript for important

intellectual content. Dr. Holloway: study concept and de-

Implementation and dissemination research sign, acquisition of data, analysis and interpretation, critical

Implementation science is the systematic study of methods to revision of the manuscript for important intellectual content,

promote the uptake and integration of research findings into study supervision.

224 Neurology | Volume 91, Number 5 | July 31, 2018 Neurology.org/N

Copyright ª 2018 American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Acknowledgment Received February 2, 2018. Accepted in final form April 6, 2018.

The authors thank the Neuropalliative Care Summit 2017

Participants Jessica Baker (Partners HealthCare, Boston, References

1. Freedman MS. Present and emerging therapies for multiple sclerosis. Continuum

MA); Kate Brizzi (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston); 2013;19:968–991.

Claudia Chou (Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN); Tara Cook 2. Morgan JC, Fox SH. Treating the motor symptoms of Parkinson disease. Continuum

2016;22:1064–1085.

(University of Pittsburgh, PA); Farrah Daly (Goodwin 3. Guzik A, Bushnell C. Stroke epidemiology and risk factor management. Continuum

House Palliative Care and Hospice, Alexandria, VA); Danny 2017;23:15–39.

4. Rabinstein AA. Treatment of acute ischemic stroke. Continuum 2017;23:62–81.

Estupinan (Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL); Corey Fehnel 5. World Health Organization. Neurological disorders: public health challenges [online]. 2006.

(Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA); Laura Available at: who.int/mental_health/neurology/neurodiso/en/. Accessed January 9, 2018.

6. Center to Advance Palliative Care. America’s Care of Serious Illness [online]. 2015.

Foster (Partners HealthCare, Boston, MA); James Grogan Available at: reportcard.capc.org/. Accessed January 1, 2018.

(Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis); Ralf 7. Kavalieratos D, Corbelli J, Zhang D, et al. Association between palliative care and

patient and caregiver outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA 2016;

Jox (Ludwig-Maximilian University, Munich, Germany, and 316:2104–2114.

Lausanne University, Switzerland); Neha Kramer (Rush 8. Higginson IJ, McCrone P, Hart SR, Burman R, Silber E, Edmonds PM. Is short-term

palliative care cost-effective in multiple sclerosis? A randomized phase II trial. J Pain

University Medical Center, Chicago, IL); Jerome Kurent Symptom Manage 2009;38:816–826.

(Medical University of South Carolina, Charleston); Judy 9. Miyasaki JM, Long J, Mancini D, et al. Palliative care for advanced Parkinson disease:

an interdisciplinary clinic and new scale, the ESAS-PD. Parkinsonism Relat Disord

Long (University of California in San Francisco); Mara 2012;18(suppl 3):S6–S9.

Lugassy (MJHS, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, New 10. Veronese S, Gallo G, Valle A, et al. Specialist palliative care improves the quality of life

in advanced neurodegenerative disorders: NE-PAL, a pilot randomised controlled

York, NY); Jerome Phillips (Mercy Health, St. Mary’s study. BMJ Support Palliat Care 2017;7:164–172.

Hospital, Michigan State University); Jorge Risco (Univer- 11. Quill TE, Abernethy AP. Generalist plus specialist palliative care: creating a more

sustainable model. N Engl J Med 2013;368:1173–1175.

sity of Rochester Medical Center, NY); Maisha Robinson 12. Holloway RG, Arnold RM, Creutzfeldt CJ, et al. Palliative and end-of-life care in

(Mayo Clinic, Jacksonville, FL); Aimee Sato (Children’s stroke: a statement for healthcare professionals from the American Heart Association/

National Health System, Washington, DC); Akanksha American Stroke Association. Stroke 2014;45:1887–1916.

13. Frontera JA, Curtis JR, Nelson JE, et al. Integrating palliative care into the care of

Sharma (University of Washington, Seattle); Christopher neurocritically ill patients: a report from the Improving Palliative Care in the ICU

Tarolli (University of Rochester Medical Center, NY); Lynne Project Advisory Board and the Center to Advance Palliative Care. Crit Care Med

2015;43:1964–1977.

Taylor (University of Washington, Seattle); Lauren Treat 14. Mitchell SL. Clinical practice: advanced dementia. N Engl J Med 2015;372:

(Children’s Hospital Colorado, Denver); Ludo Vanopden- 2533–2540.

15. Miller RG, Jackson CE, Kasarskis EJ, et al. Practice parameter update: the care of the

bosch (AZ Sint Jan Hospital, Brugge, Belgium); Anastasia patient with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: multidisciplinary care, symptom manage-

Vishnevetsky (Partners Health System, Boston, MA); Neal ment, and cognitive/behavioral impairment (an evidence-based review): report of the

Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology

Weisbrod (University of Rochester Medical Center, NY). 2009;73:1227–1233.

16. Institute of Medicine of the National Academies. Dying in America: Improving

Quality and Honoring Individual Preferences Near the End of Life. 1st ed. Wash-

Study funding ington, DC: National Academies Press; 2015.

No targeted funding reported. 17. Palliative care in neurology. The American Academy of Neurology Ethics and Hu-

manities Subcommittee. Neurology 1996;46:870–872.

18. Braun LT, Grady KL, Kutner JS, et al. Palliative care and cardiovascular disease and

stroke: a policy statement from the American Heart Association/American Stroke

Disclosure Association. Circulation 2016;134:e198–e225.

C. Creutzfeldt receives funding from the NIH–National Insti- 19. Bosslet GT, Pope TM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. An official ATS/AACN/ACCP/ESICM/

SCCM policy statement: responding to requests for potentially inappropriate treat-

tutes of Neurological Disease and Stroke (NINDS) (K23 ments in intensive care units. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2015;191:1318–1330.

NS099421). B. Kluger receives funding from the National 20. Nelson JE, Bassett R, Boss RD, et al. Models for structuring a clinical initiative to

enhance palliative care in the intensive care unit: a report from the IPAL-ICU

Institutes of Nursing Research (NINR), NINDS, Patient Cen- project (improving palliative care in the ICU). Crit Care Med 2010;38:

tered Outcome Research Institute (PCORI): Improving 1765–1772.

21. Cox CE, Curtis JR. Using technology to create a more humanistic approach to

Healthcare Systems, NIH, and the Davis Phinney Foundation; integrating palliative care into the intensive care unit. Am J Respir Crit Care Med

he has served as an expert witness for Elite Medical Experts, 2016;193:242–250.

Carlson & Carlson, Chayet & Danzo, and Elizabeth A. Kleger & 22. Melvin TA. The primary care physician and palliative care. Prim Care 2001;28:

239–249.

Associates; and he receives honorarium for speaking for the 23. Hui D, Bruera E. Models of integration of oncology and palliative care. Ann Palliat

Davis Phinney Foundation. A. Kelly reports no disclosures rel- Med 2015;4:89–98.

24. Gandesbery B, Dobbie K, Gorodeski EZ. Outpatient palliative cardiology service

evant to the manuscript. M. Lemmon receives funding from the embedded within a heart failure clinic: experiences with an emerging model of care.

National Palliative Care Research Center Career Development Am J Hosp Palliat Care 2018;35:635–639.

25. Blackhall LJ. Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis and palliative care: where we are, and the

Award. D. Hwang reports no disclosures relevant to the man- road ahead. Muscle Nerve 2012;45:311–318.

uscript. N. Galifianakis received a philanthropic gift from Dor- 26. Su KG, Carter JH, Tuck KK, et al. Palliative care for patients with Parkinson’s disease:

an interdisciplinary review and next step model. J Parkinsonism Restless Legs Syndr

skind Family Foundation and receives research support from 2016;7:1–12.

Boston Scientific Corporation, NIH, and PCORI. A. Carver 27. Kluger BM, Fox S, Timmons S, et al. Palliative care and Parkinson’s disease: meeting

summary and recommendations for clinical research. Parkinsonism Relat Disord

reports no disclosures relevant to the manuscript. M. Katz 2017;37:19–26.

receives funding from the Patient Centered Outcomes Research 28. Worster B, Swartz K. Telemedicine and palliative care: an increasing role in supportive

oncology. Curr Oncol Rep 2017;19:37.

Institute and NIH-NINR (R01 NR016037). J. Curtis receives 29. Creutzfeldt CJ, Holloway RG, Curtis JR. Palliative care: a core competency for stroke

funding from the Cambia Health Foundation. R. Holloway neurologists. Stroke 2015;46:2714–2719.

30. Prabhakaran S, Cox M, Lytle B, et al. Early transition to comfort measures only in

receives funding from the NIH and NY State Department of acute stroke patients: analysis from the Get With The Guidelines-Stroke registry.

Health. Go to Neurology.org/N for full disclosures. Neurol Clin Pract 2017;7:194–204.

Neurology.org/N Neurology | Volume 91, Number 5 | July 31, 2018 225

Copyright ª 2018 American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

31. Robinson MT, Vickrey BG, Holloway RG, et al. The lack of documentation of 45. Mack JW, Weeks JC, Wright AA, Block SD, Prigerson HG. End-of-life discussions,

preferences in a cohort of adults who died after ischemic stroke. Neurology 2016;86: goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of

2056–2062. care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol 2010;28:1203–1208.

32. Singh T, Peters SR, Tirschwell DL, Creutzfeldt CJ. Palliative care for hospitalized 46. Fadul N, Elsayem A, Palmer JL, et al. Supportive versus palliative care: what’s in

patients with stroke: results from the 2010 to 2012 national inpatient sample. Stroke a name? A survey of medical oncologists and midlevel providers at a comprehensive

2017;48:2534–2540. cancer center. Cancer 2009;115:2013–2021.

33. Miller RG, Brooks BR, Swain-Eng RJ, et al. Quality improvement in neurology: 47. Rhondali W, Burt S, Wittenberg-Lyles E, Bruera E, Dalal S. Medical oncologists’

amyotrophic lateral sclerosis quality measures: report of the Quality Measurement perception of palliative care programs and the impact of name change to supportive

and Reporting Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology. Neurology care on communication with patients during the referral process: a qualitative study.

2013;81:2136–2140. Palliat Support Care 2013;11:397–404.

34. Sanders AE, Nininger J, Absher J, Bennett A, Shugarman S, Roca R. Quality im- 48. Creutzfeldt CJ, Robinson MT, Holloway RG. Neurologists as primary palliative care

provement in neurology: dementia management quality measurement set update. providers: communication and practice approaches. Neurol Clin Pract 2016;6:40–48.

Neurology 2017;88:1951–1957. 49. Sigsbee B, Bernat JL. Physician burnout: a neurologic crisis. Neurology 2014;83:

35. Factor SA, Bennett A, Hohler AD, Wang D, Miyasaki JM. Quality improvement in 2302–2306.

neurology: Parkinson disease update quality measurement set: executive summary. 50. Creutzfeldt CJ, Holloway RG. Treatment decisions after severe stroke: uncertainty

Neurology 2016;86:2278–2283. and biases. Stroke 2012;43:3405–3408.

36. Josephson SA, Ferro J, Cohen A, Webb A, Lee E, Vespa PM. Quality improvement in 51. Sanders JJ, Curtis JR, Tulsky JA. Achieving goal-concordant care: a conceptual model

neurology: inpatient and emergency care quality measure set: executive summary. and approach to measuring serious illness communication and its impact. J Palliat

Neurology 2017;89:730–735. Med 2018;21:S17–S27.

37. National Quality Forum. Palliative and End-of-Life Care 2015–2016 [online]. 2017. 52. Dzau VJ, McClellan MB, McGinnis JM, et al. Vital directions for health and health care:

Available at: qualityforum.org/Palliative_and_End-of-Life_Care_Project_2015-2016. priorities from a National Academy of Medicine Initiative. JAMA 2017;317:1461–1470.

aspx. Accessed January 8, 2018. 53. Turnbull AE, Hartog CS. Goal-concordant care in the ICU: a conceptual framework

38. Curtis JR, Sathitratanacheewin S, Starks H, et al. Using electronic health records for for future research. Intensive Care Med 2017;43:1847–1849.

quality measurement and accountability in care of the seriously ill: opportunities and 54. Kapoor A, Lanctot KL, Bayley M, et al. “Good outcome" isn’t good enough: cognitive

challenges. J Palliat Med 2018;21:S52–S60. impairment, depressive symptoms, and social restrictions in physically recovered

39. Schenker Y, Arnold R. The next era of palliative care. JAMA 2015;314:1565–1566. stroke patients. Stroke 2017;48:1688–1690.

40. Dy SM, Kiley KB, Ast K, et al. Measuring what matters: top-ranked quality indicators 55. Harding R, Gao W, Jackson D, Pearson C, Murray J, Higginson IJ. Comparative

for hospice and palliative care from the American Academy of Hospice and Palliative analysis of informal caregiver burden in advanced cancer, dementia, and acquired

Medicine and Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association. J Pain Symptom Manage brain injury. J Pain Symptom Manage 2015;50:445–452.

2015;49:773–781. 56. George BP, Kelly AG, Schneider EB, Holloway RG. Current practices in feeding tube

41. Pantilat SZ, Marks AK, Bischoff KE, Bragg AR, O’Riordan DL. The palliative care placement for US acute ischemic stroke inpatients. Neurology 2014;83:874–882.

quality network: improving the quality of caring. J Palliat Med 2017;20:862–868. 57. Kilbourne AM, Switzer G, Hyman K, Crowley-Matoka M, Fine MJ. Advancing health

42. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Frequently asked questions about billing the disparities research within the health care system: a conceptual framework. Am J

Physician Fee Schedule for advance care planning services [online]. 2016. Available at: Public Health 2006;96:2113–2121.

cms.gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/PhysicianFeeSched/Downloads/ 58. Creutzfeldt CJ, Engelberg RA, Healey L, et al. Palliative care needs in the neuro-ICU.

FAQ-Advance-Care-Planning.pdf. Accessed July 17, 2017. Crit Care Med 2015;43:1677–1684.

43. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Hospice [online]. 2017. Available at: cms. 59. Glod SA. The other victims of the opioid epidemic. N Engl J Med 2017;376:2101–2102.

gov/Medicare/Medicare-Fee-for-Service-Payment/Hospice/index.html. Accessed 60. Shalowitz DI, Garrett-Mayer E, Wendler D. The accuracy of surrogate decision

September 25, 2017. makers: a systematic review. Arch Intern Med 2006;166:493–497.

44. Drury L, Baccari K, Fang A, Moller C, Nagus I. Providing intensive palliative care on 61. Peters DH, Adam T, Alonge O, Agyepong IA, Tran N. Implementation research: what

an inpatient unit: a full-time job. J Adv Pract Oncol 2016;7:60–64. it is and how to do it. BMJ 2013;347:f6753.

Did You Know…

…you can browse by subspecialty topics on Neurology.org?

Go to: Neurology.org and click on “Topics” in the top navigation bar.

Committed to Making a Difference: 2019 American Academy of Neurology

Research Program

The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) is committed to making a profound difference in the lives of researchers, in turn

making a difference in the lives of patients with brain disease. The ambitious 2019 AAN Research Program offers opportunities

ranging from $130,000 to $450,000 and designed for all types of research across all career levels and discovery stages. Pave your

own pathway to patient care by applying for one of the opportunities by the October 1, 2018, deadline.

Visit AAN.com/view/ResearchProgram today.

226 Neurology | Volume 91, Number 5 | July 31, 2018 Neurology.org/N

Copyright ª 2018 American Academy of Neurology. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

You might also like

- Nikki Blackketter - 6 Week Booty Building ProgrampdfDocument16 pagesNikki Blackketter - 6 Week Booty Building ProgrampdfkulsoomNo ratings yet

- Thesis Topics On Business EducationDocument5 pagesThesis Topics On Business Educationjennyhillminneapolis100% (1)

- John D. Huber - Charles R. Shipan - Deliberate Discretion - The Institutional Foundations of Bureaucratic Autonomy-Cambridge University Press (2002)Document303 pagesJohn D. Huber - Charles R. Shipan - Deliberate Discretion - The Institutional Foundations of Bureaucratic Autonomy-Cambridge University Press (2002)Caio RamosNo ratings yet

- Neuroscience Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeFrom EverandNeuroscience Nursing: Scope and Standards of PracticeRating: 5 out of 5 stars5/5 (2)

- Juan Carlos Vsim Prep 3Document5 pagesJuan Carlos Vsim Prep 3Michelle Pinkhasova100% (3)

- 409 FullDocument9 pages409 FullSimone GavelliNo ratings yet

- Palliative Care in Nephrology: The Work and The Workforce: Table 1Document7 pagesPalliative Care in Nephrology: The Work and The Workforce: Table 1Kev Jose Ruiz RojasNo ratings yet

- JOURNAL 4_RICHARDDocument4 pagesJOURNAL 4_RICHARDEure AlejandrinoNo ratings yet

- Supporting and Empowering People With Epilepsy Contribution of The Epilepsy Specialist NursesDocument8 pagesSupporting and Empowering People With Epilepsy Contribution of The Epilepsy Specialist Nursescelia.longuetNo ratings yet

- J J. C C - Pitman: Nov/DecDocument13 pagesJ J. C C - Pitman: Nov/DecDianne Ingusan-TangNo ratings yet

- PSY-Mood DisordersDocument185 pagesPSY-Mood DisordersDelaNo ratings yet

- Deliberate Self Harm CPGDocument109 pagesDeliberate Self Harm CPGyhhyhhNo ratings yet

- Palliative Care and End-Of-Life Care in Adults With Malignant Brain TumorsDocument10 pagesPalliative Care and End-Of-Life Care in Adults With Malignant Brain TumorsLaras Adythia PratiwiNo ratings yet

- Nihms 1598170Document3 pagesNihms 1598170Mario SerranoNo ratings yet

- A Clinical Pathway To Standardize Care of Children With Delirium in Pediatric Inpatient Settings-2019Document10 pagesA Clinical Pathway To Standardize Care of Children With Delirium in Pediatric Inpatient Settings-2019Juan ParedesNo ratings yet

- Neurosurg Focus Article Pe14Document7 pagesNeurosurg Focus Article Pe14jojost14No ratings yet

- Neuropsicología GeriátricaDocument3 pagesNeuropsicología GeriátricaFrancisco LopezNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Management of Acute Cervical Spinal InjuriesDocument202 pagesGuidelines For Management of Acute Cervical Spinal InjuriesMuhammad IrfanNo ratings yet

- Neuro-Oncology Practice: Integration of Palliative Care Into The Neuro-Oncology Practice: Patterns in The United StatesDocument5 pagesNeuro-Oncology Practice: Integration of Palliative Care Into The Neuro-Oncology Practice: Patterns in The United StatessiscaNo ratings yet

- Pengkajian Riwayat Dan Pemeriksaan Fisik Pasian PaliatifDocument7 pagesPengkajian Riwayat Dan Pemeriksaan Fisik Pasian PaliatifnrjNo ratings yet

- Emergency Neurologic Life Support (ENLS) - Evolution of Management in The First Hour of A Neurological EmergencyDocument4 pagesEmergency Neurologic Life Support (ENLS) - Evolution of Management in The First Hour of A Neurological Emergencyandrés Felipe CepedaNo ratings yet

- Analysis: Palliative Care From Diagnosis To DeathDocument5 pagesAnalysis: Palliative Care From Diagnosis To DeathFernanda FerreiraNo ratings yet

- Pediatric Hydrocephalus: Systematic Literature Review and Evidence-Based Guidelines. Part 1: Introduction and MethodologyDocument5 pagesPediatric Hydrocephalus: Systematic Literature Review and Evidence-Based Guidelines. Part 1: Introduction and MethodologyagusNo ratings yet

- Improving Long-Term Outcomes After Discharge From Intensive Care Unit: Report From A Stakeholders' ConferenceDocument8 pagesImproving Long-Term Outcomes After Discharge From Intensive Care Unit: Report From A Stakeholders' ConferenceRodrigoSachiFreitasNo ratings yet

- Critical Care Management of Patients After Cardiac Arrest: A Scientific Statement From The American Heart Association and Neurocritical Care SocietyDocument37 pagesCritical Care Management of Patients After Cardiac Arrest: A Scientific Statement From The American Heart Association and Neurocritical Care SocietyndfelicianoNo ratings yet

- A Community Based Program For PDFDocument9 pagesA Community Based Program For PDFana irianiNo ratings yet

- Neuro-Oncology Training For The Child Neurology ResidentDocument7 pagesNeuro-Oncology Training For The Child Neurology ResidentMaurycy RakowskiNo ratings yet

- Historia de La PsicooncologiaDocument54 pagesHistoria de La PsicooncologiaLiana Pérez RodríguezNo ratings yet

- JHPN 24 E151Document8 pagesJHPN 24 E151MentiEndah dwi SeptianiNo ratings yet

- Management of DementiaDocument16 pagesManagement of DementiaAndris C BeatriceNo ratings yet

- Core Components of Palliative CareDocument6 pagesCore Components of Palliative CareDianitha Loarca RodríguezNo ratings yet

- Guidelines For Neuroprognostication in Adults With Traumatic Spinal Cord InjuryDocument23 pagesGuidelines For Neuroprognostication in Adults With Traumatic Spinal Cord Injurymarius vaidaNo ratings yet

- Emergency Neurological Life Support: Fourth Edition, Updates in The Approach To Early Management of A Neurological EmergencyDocument5 pagesEmergency Neurological Life Support: Fourth Edition, Updates in The Approach To Early Management of A Neurological Emergencyalejandro montesNo ratings yet

- NandaDocument28 pagesNandaसपना दाहालNo ratings yet

- Patient-Clinician CommunicationDocument17 pagesPatient-Clinician CommunicationFreakyRustlee LeoragNo ratings yet

- 1 s2.0 S1755599X20301014 MainDocument11 pages1 s2.0 S1755599X20301014 MainNers EducationNo ratings yet

- Surviving Sepsis Campaign International Guidelines For The Management of Septic Shock and Sepsis Associated Organ Dysfunction in ChildrenDocument58 pagesSurviving Sepsis Campaign International Guidelines For The Management of Septic Shock and Sepsis Associated Organ Dysfunction in ChildrenmarianaglteNo ratings yet

- Palliative Care For Adults.Document28 pagesPalliative Care For Adults.Madalina TalpauNo ratings yet

- Agitation Clinical Guidelines APPMDocument10 pagesAgitation Clinical Guidelines APPMJulio César Sánchez MarínNo ratings yet

- The Neuroethics of Disorders of ConsciousnessDocument20 pagesThe Neuroethics of Disorders of ConsciousnessNora Solana LlorenteNo ratings yet

- PIIS0140673621015968Document11 pagesPIIS0140673621015968James AmaroNo ratings yet

- Kluger 2019Document3 pagesKluger 2019Ana LopezNo ratings yet

- Educational Strategies To Promote Clinical Diagnostic Reasoning. N Engl J Med. 2006Document13 pagesEducational Strategies To Promote Clinical Diagnostic Reasoning. N Engl J Med. 2006Julio CidNo ratings yet

- RetrieveDocument26 pagesRetrievemarta_gasparNo ratings yet

- 1 SPDocument14 pages1 SPharveymethinksNo ratings yet

- 2020 SSC Guidelines For Septic Shock in Children PDFDocument58 pages2020 SSC Guidelines For Septic Shock in Children PDFAtmaSearch Atma JayaNo ratings yet

- Contents CCCDocument4 pagesContents CCCSAMUEL SANCHEZNo ratings yet

- Hawk Et Al 2020 Best Practices For Chiropractic Management of Patients With Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain A ClinicalDocument18 pagesHawk Et Al 2020 Best Practices For Chiropractic Management of Patients With Chronic Musculoskeletal Pain A ClinicalFRANCISCO JAVIER HOYOS QUINTERONo ratings yet

- Neurogenic Bowel ManagementDocument51 pagesNeurogenic Bowel ManagementAndrei TarusNo ratings yet

- Engaging People With Chronic Kidney Disease in Their Own Care An Integrative ReviewDocument10 pagesEngaging People With Chronic Kidney Disease in Their Own Care An Integrative ReviewyutefupNo ratings yet

- Improvement in Quality MetricsDocument10 pagesImprovement in Quality MetricsGodFather xNo ratings yet

- Psychology Guideline - Long Version With Supp DataDocument13 pagesPsychology Guideline - Long Version With Supp DataShobhitNo ratings yet

- NURS FPX4900 Roxy ObiesieElizabeth Assessment4PartB 1Document11 pagesNURS FPX4900 Roxy ObiesieElizabeth Assessment4PartB 1Jeffrey MwendwaNo ratings yet

- 2 El Cuidado Del Paciente HollandDocument3 pages2 El Cuidado Del Paciente HollandMechi FariasNo ratings yet

- Patient Centerdness in Physiotherapy WhaDocument2 pagesPatient Centerdness in Physiotherapy Whapedroperestrelo96No ratings yet

- Neuropathic Pain: Principles of Diagnosis and Treatment: Symposium On Pain MedicineDocument14 pagesNeuropathic Pain: Principles of Diagnosis and Treatment: Symposium On Pain MedicineWahyu AlfianNo ratings yet

- CP Cholecystitis With Cholethiasis, Mild Dehydration CAPDocument181 pagesCP Cholecystitis With Cholethiasis, Mild Dehydration CAPArianna Jasmine MabungaNo ratings yet

- Mathew 2017Document6 pagesMathew 2017GodlipNo ratings yet

- Niemann 37Document19 pagesNiemann 37banitavlad5No ratings yet

- Assignment No. 1Document1 pageAssignment No. 1Clau MagahisNo ratings yet

- ImportantDocument15 pagesImportantanimut alebelNo ratings yet

- Definitions and Drivers of Relapse in Patients With Skizofrenia Sistematic ReviewDocument11 pagesDefinitions and Drivers of Relapse in Patients With Skizofrenia Sistematic ReviewMiftakhul UlfahNo ratings yet

- Care Givers Burden Neck and Reast CancerDocument21 pagesCare Givers Burden Neck and Reast Cancerseyfedin BarkedaNo ratings yet

- Focus: NeurosurgicalDocument12 pagesFocus: NeurosurgicalMohammed Ali AlviNo ratings yet

- Records and ReportsDocument23 pagesRecords and ReportsKhusbu MalequeNo ratings yet

- Aia All in One BrochureDocument4 pagesAia All in One BrochureGenelyn LangoteNo ratings yet

- Test For Unit 2Document4 pagesTest For Unit 2Cơm CụcNo ratings yet

- TCF - Contractor's Site Safety ProgrameditedDocument148 pagesTCF - Contractor's Site Safety ProgrameditedSabre Alam0% (1)

- Mindful Hypnotherapy To Reduce Stress and Increase Mindfulness A Randomized Controlled Pilot StudyDocument17 pagesMindful Hypnotherapy To Reduce Stress and Increase Mindfulness A Randomized Controlled Pilot StudyHendro SantosoNo ratings yet

- Top Ten Acute Ultrasound Emergencies On-Call Key Learning Points For The Radiology Registrar.Document1 pageTop Ten Acute Ultrasound Emergencies On-Call Key Learning Points For The Radiology Registrar.KimberlyNo ratings yet

- Malpractice Negligence 1Document22 pagesMalpractice Negligence 1yen.pelaezNo ratings yet

- DNV GL TecRegNews No 13 2020Document2 pagesDNV GL TecRegNews No 13 2020Achraf Ben DhifallahNo ratings yet

- Mental Health Act 1987Document35 pagesMental Health Act 1987P Vinod Kumar100% (1)

- How Old Is The Youngest Mother in The World - Google SearchDocument1 pageHow Old Is The Youngest Mother in The World - Google SearchОюу-Эрдэнэ Э.No ratings yet

- Fall Protection - Toolbox Talk - EnglishDocument1 pageFall Protection - Toolbox Talk - EnglishJomy JohnyNo ratings yet

- History of The Nursing ProfessionDocument3 pagesHistory of The Nursing Professionedwin GikundaNo ratings yet

- Children Trafficking ScriptDocument2 pagesChildren Trafficking ScriptArabel O'CallaghanNo ratings yet

- HEALTH REAC 4 Physicians by CategoriesDocument43 pagesHEALTH REAC 4 Physicians by CategoriesMahmoudNo ratings yet

- 2024 UNSW Gateway Admission Pathway Adjusted ATARs 300623Document5 pages2024 UNSW Gateway Admission Pathway Adjusted ATARs 300623kushinauzamaki101No ratings yet

- Sepsis Infographic A3Document2 pagesSepsis Infographic A3enricoNo ratings yet

- Results of The DataDocument7 pagesResults of The DataaninNo ratings yet

- Dissertation Medical TourismDocument7 pagesDissertation Medical TourismBuyingCollegePapersPittsburgh100% (1)

- Emotify: Predict Interpersonal, Team and Leadership EffectivenessDocument2 pagesEmotify: Predict Interpersonal, Team and Leadership EffectivenessNisharNo ratings yet

- Project 2023 1 LT02 KA152 YOU 000141409Document4 pagesProject 2023 1 LT02 KA152 YOU 000141409ognjennNo ratings yet

- The Tree of LightDocument25 pagesThe Tree of LightLeonel KongaNo ratings yet

- Health Declaration FormDocument2 pagesHealth Declaration FormCATHERINE FAJARDONo ratings yet

- Chap 07Document8 pagesChap 07rumel khaledNo ratings yet

- VSTEP Writing 1,2,3 2024 2025 p.240 and More TopicsDocument20 pagesVSTEP Writing 1,2,3 2024 2025 p.240 and More TopicsPhong ViNo ratings yet

- The Impact of Social Media On SocietyDocument2 pagesThe Impact of Social Media On Societya40198617No ratings yet

- Free Thyroxine (FT4) Test Kit (Homogeneous Chemiluminescence Immunoassay) Instruction For Use A0Document2 pagesFree Thyroxine (FT4) Test Kit (Homogeneous Chemiluminescence Immunoassay) Instruction For Use A0Asesoria TecnicaNo ratings yet