Meatqualityinspection-Review

Uploaded by

hnaalmhmdyCopyright:

Available Formats

Meatqualityinspection-Review

Uploaded by

hnaalmhmdyCopyright

Available Formats

Share this document

Did you find this document useful?

Is this content inappropriate?

Copyright:

Available Formats

Meatqualityinspection-Review

Uploaded by

hnaalmhmdyCopyright:

Available Formats

See discussions, stats, and author profiles for this publication at: https://www.researchgate.

net/publication/286926399

Optical Methods and Techniques for Meat Quality Inspection

Article in Transactions of the ASABE (American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers) · July 2015

DOI: 10.13031/trans.58.11004

CITATIONS READS

29 4,721

2 authors, including:

Sagar Dhakal

United States Department of Agriculture

62 PUBLICATIONS 1,103 CITATIONS

SEE PROFILE

All content following this page was uploaded by Sagar Dhakal on 10 February 2016.

The user has requested enhancement of the downloaded file.

OPTICAL METHODS AND TECHNIQUES

FOR MEAT QUALITY INSPECTION

Y. Peng, S. Dhakal

ABSTRACT. Meat and meat products are closely associated with the daily eating habits of people around the world.

Quality monitoring of meat and meat products is essential to ensure public health. In recent years, the meat industry has

employed state-of-the art, high-speed processing technology, and meat processors need rapid, non-destructive, easy-to-

use technology to monitor the safety and quality of meats and meat products for economic benefit. Optical technology has

been gaining importance in research and industrial applications for real-time, non-destructive, accurate measurement of

the quality attributes of meat and meat products. Hyperspectral imaging, multispectral imaging, visible-near-infrared

(Vis/NIR) spectroscopy, and machine vision are used in research and industry for detection of the physical, chemical, sen-

sory, and microbiological attributes of meat and meat products. These optical technologies have shown potential for ac-

curate detection of individual attributes as well as multiple attributes simultaneously. This article reviews these optical

technologies for detecting the quality attributes of meat (especially beef, pork, lamb, and poultry). This article also dis-

cusses the prevailing challenges for practical application of optical technologies and future research prospects.

Keywords. Industrial application, Meat, Non-destructive, Optical technology, Rapid, Real-time.

E

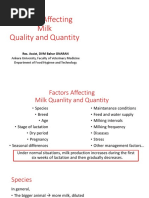

conomic development has lifted the living stand- Chemical attributes are responsible for the nutritional value

ards of people around the world. Along with im- of meat. Microbiological organisms, such as bacterial con-

proved living standards, the meat industry has tamination, present a safety hazard in meat and are respon-

seen a massively increased demand for meat and sible for spoilage. Sensory attributes, such as color, smell,

meat products. Meat and meat products have become an flavor, and tenderness, directly influence the purchasing

important part of the daily diet for people around the world. decisions of consumers, as they provide the first impression

It has been reported that, over the past 50 years, global of meat quality.

meat consumption has quadrupled from 70 million tons in The above-mentioned attributes determine the overall

1961 to 283 million tons in 2011 (Tao and Peng, 2014). quality of meat. However, these attributes are mainly ap-

With growing consumption of meat and meat products, the plied to red meat and represent the quality of poultry meat

public has become more conscious of meat quality attrib- to a lesser extent. In poultry, fecal matter and ingesta are

utes. Meat quality is thus one of the important factors that the primary sources of carcass contamination by microbial

contribute to meat prices and to the purchasing decisions of pathogens. Physicochemical, biochemical, and microbio-

consumers. logical properties, including moisture content, water activi-

Meat quality can be defined as a measurement of the pa- ty, pH, total volatile basic nitrogen (TVB-N), and bacterial

rameters, attributes, and characteristics that determine the contamination, determine the freshness of chicken meat.

suitability for consumption of fresh or stored meat without Hence, it can be concluded that the quality attributes of

any deterioration for a certain period of time (ElMasry et meat can be broadly classified into the four categories re-

al., 2012b). Meat quality includes physical qualities, chem- gardless of the type of meat (fig. 1).

ical composition and nutritional content, microbiological Meat quality is influenced by many factors, from animal

organisms in the meat, and sensory attributes, as shown in breeding, growth, and slaughter, to packaging, storage, and

figure 1. Physical qualities include factors such as marbling transportation, and finally to cooking. This means that meat

and water-holding capacity (WHC). Chemical composition

and nutritional content, such as protein, fat, calcium, and Meat Quality

moisture content, represent the chemical attributes of meat.

Submitted for review in October 2014 as manuscript number PRS

11004; approved for publication by the Processing Systems Community of Physical Chemical and Microbiological Sensory

ASABE in July 2015. Attributes Nutrition Organisms Attributes

The authors are Yankun Peng, ASABE Member, Professor, and

Sagar Dhakal, Doctoral Student, College of Engineering, National R&D marbling, protein, alcium, bacterial color,

Center for Agro-Processing Equipment, China Agricultural University, water holding fat, moisture, contamination, smell, flavor,

Beijing, China. Corresponding author: Yankun Peng, 17 Qinghua East capacity, etc pH, etc etc tenderness, etc

Road, Haidian, Beijing 100083, China; phone: 86-01-62737703; e-mail:

ypeng@cau.edu.cn. Figure 1. Quality attributes of meat in general.

Transactions of the ASABE

Vol. 58(5): 1371-1386 © 2015 American Society of Agricultural and Biological Engineers ISSN 2151-0032 DOI 10.13031/trans.58.11004 1371

has a high risk of deterioration through the entire produc- compared to manual inspection, they require long pro-

tion chain, from breeding to consumption. The meat indus- cessing times, complex sample preparation, and trained

try is currently facing the challenge of obtaining reliable technicians, and they are destructive. Instrument methods

information on meat quality throughout the production pro- and chemical analysis cannot satisfy the meat industry’s

cess, to ensure the quality of meat products provided to need for fast, reliable, accurate, and non-destructive detec-

consumers (Tao and Peng, 2014). tion of meat quality.

Meat is also highly perishable due to its high nutritional Recent years have seen rapid advances in meat quality

content. The chemical composition and sensory attributes detection methods. Various methods have been reported in

of meat are highly influenced by pre-slaughter factors the literature for detection of the quality attributes of meat

(breed, sex, age, weight, and environment) and post- and meat products. Among these methods, biosensors have

mortem factors (storage time, temperature, etc.) (Andres et gained importance for detection of meat quality attributes

al., 2007; Lawrie, 1985). Pre-slaughter and post-mortem (Balasubramanian et al., 2009; Damez et al., 2008; Haugen

changes cause quality deterioration in meat, thus requiring et al., 2006; Ohk and Bhunia, 2013; Panigrahi et al., 2006;

reliable technology for meat quality determination before Zor et al., 2011). Although biosensors can provide rapid

consumption. Traditionally, trained inspectors were em- detection with satisfactory accuracy, they cannot satisfy the

ployed to detect meat quality attributes manually (Xiong et meat industry’s need because of their destructive nature.

al., 2014). Sensory attributes, such as tenderness, were as- Meanwhile, optical technologies have received wide atten-

sessed by pressing the meat, flavor was assessed by smell- tion in the research community because of their rapid, non-

ing the meat, and color and marbling were evaluated by destructive, real-time, and precise detection ability (Gomez

comparing the color of the rib eye muscle (musculus et al., 2006; Jamshidi et al., 2012; Lu and Peng, 2006; Pan

longissimus dorsi) or the proportion of intramuscular fat et al., 2015; Peng and Lu, 2007; Qin et al., 2013; Xue et al.,

within the m. longissimus dorsi against reference standards 2012; Zhang et al., 2014). Consequently, optical technolo-

for each meat species. However, manual inspection cannot gies are gaining importance in industrial automation (Li et

evaluate the internal quality attributes of meat, such as nu- al., 2011a; Mehta and Burks, 2014; Tong et al., 2013).

tritional content, pH, moisture content, presence of micro- Much effort has been made in the research and devel-

organism, and so on. Manual inspection is also tedious and opment of optical technologies for detection of the internal

subjective and depends strongly on the inspector’s alertness and external quality attributes of meat. Rapid, non-

and fatigue. Poultry carcasses are inspected visually for destructive, real-time, and precise detection of the physical,

surface contaminants such as ingesta and feces. The typical chemical, sensory, and microbiological quality attributes of

U.S. poultry processor handles 140 to 180 birds per minute meat and meat products from the start of the process to

on each processing line (Yoon et al., 2011). Although ex- consumption will protect public health, promote meat con-

ternal and sensory quality attributes can be evaluated by sumption, and provide an economic benefit for the meat

human inspectors, internal quality attributes, such as nutri- industry. This article reviews the optical technologies used

tion content, micro-organisms, pH level, and TVB-N con- for rapid and non-destructive detection of internal and ex-

tent, are difficult or impossible to detect by human inspec- ternal quality attributes of meat.

tion.

Instrument methods and chemical analysis have been

used for detection of internal quality attributes of meat for MAIN OPTICAL TECHNOLOGIES

decades. Such methods are effective and considered relia- Modern agricultural and food industries have seen rapid

ble for their consistent results. Instrument methods such as application of optical technologies for detection of the qual-

Warner-Bratzler shear force (WBSF) have been widely ity attributes of fruits, vegetables, meat and meat products,

used for evaluating meat tenderness, a pH meter inserted eggs and egg products, fish, processed products, etc. (Du

into a meat sample has long been used for pH measure- and Sun, 2008; Dowlati et al., 2012; ElMasry et al., 2012b;

ment, and meat color is evaluated using colorimeters. These Feng et al., 2008; Ji et al., 2012; Kimiya et al., 2013; Lee-

instruments are used to evaluate the texture or freshness of mans et al., 1998; Lin et al., 2011; Yao et al., 2014). Opti-

meat. Similarly, chemical methods, such as Kjeldahl, are cal technologies have proven their potential in a wide range

used for protein analysis (Xiong et al., 2014a), and other of applications in agriculture and food. The reflectance,

solvent methods are used for measuring fat content. The transmittance, and absorption of incident light on a sample

plate count method has long been used for detection of mi- depend on the sample’s chemical and physical properties,

cro-organisms in meat. Meat is prone to spoilage during and these relationships provide a detection mechanism for

storage due to microbial activity. Conventional laboratory optical technology. The interaction of light with the sample

analysis methods, such as high-performance liquid chroma- surface can be used to detect surface properties. Hence, by

tography (HPLC) and ultra-high performance liquid chro- illuminating the sample surface, we can capture a surface

matography tandem mass spectrometry, are used for detec- image with a camera. Scattering of light occurs due to in-

tion of meat quality based on spoilage status, chemical con- teraction of the incident light with the chemical and physi-

tent such as inulin, contaminant residue, foodborne patho- cal properties of the sample, causing changes in the direc-

gens, and other chemical constituents (Argyri et al., 2011; tion of light propagation. Scattering characteristics can be

Boselli et al., 2008; Clariana et al., 2010; Shalaby et al., quantified using mathematical models for nondestructive

2011; Vendrell-Pascuas et al., 2000; Xu et al., 2012). Alt- detection of different chemical and physical properties. The

hough these methods have proven consistent and reliable

1372 TRANSACTIONS OF THE ASABE

amount and pattern of light scattering depends on different

factors, such as the wavelength of the incident light, the Connection Cable

penetration of the incident light, the physical and chemical

CCD Camera

properties of the sample, and the sample’s refraction index,

to name a few.

Depending on the application, optical technologies can Imaging Spectrograph

be broadly classified as spectroscopy, machine vision, and

Computer

hyperspectral imaging. Spectroscopy is used to establish Light Source Lens Light Source

the relationship between the electromagnetic radiation and

the sample to develop a chemometrics model for detecting

different quality attributes of the sample. Spectral data col-

lected from a point or small area on the sample surface are

used to develop the chemometrics model. A spectroscopic Controller

system consists of a spectrometer, a light source, an optical Sample

x y

probe, a controller, and related software. Spectroscopy sys- Moving Platform

Speed

tems have been developed for different wavelength ranges,

such as Vis/NIR, infrared, UV, etc. Spectroscopy can be

used only for point scans, and it does not provide spatial Figure 2. Schematic of hyperspectral imaging system.

information. A spectroscopic system is generally used to

detect the chemical constituents of a sample for quality QUALITY INSPECTION BY HYPERSPECTRAL IMAGING

measurement, such as the freshness of meat (Prieto et al., Among the different types of meat, red meats such as

2009a, 2009b; Venel et al., 2001). beef, lamb, and pork are widely consumed due to their high

Machine vision (also called computer vision) is mostly nutritional value. With increasing consumption, technolo-

used for detecting external quality attributes of samples gies for quality detection of red meat are also advancing

through analysis of digital images. Machine vision analyzes rapidly. State-of-the-art hyperspectral imaging technology

the spatial information obtained from digital images of and the corresponding algorithms for non-destructive and

samples, such as color, size, and surface structure. As such, rapid detection of various quality attributes of red meat

the application of machine vision is mainly limited to sur- have been reported in the literature. Hyperspectral imaging

face detection. A machine vision system generally consists has been applied for detection of nutritional content, mois-

of a CCD camera, a light source, a computer, and related ture content, pH, tenderness, microbial spoilage, WHC,

software. Machine vision systems have been widely used in marbling, drip loss, and color.

agriculture and food for detection of surface quality charac-

Beef

teristics (i.e., color, size, shape, etc.) (Chmiel et al., 2011a,

Chemical and nutritional attributes are important factors

2011b; Penman, 2001; Zhang et al., 2015).

in determining the quality of red meat. The chemical con-

Hyperspectral imaging combines features of imaging

stituents in red meat, such as protein, fat, fatty acids, and

and spectroscopy, enabling it to detect the external charac-

moisture, affect the quality of red meat, and chemical reac-

teristics of a sample by imaging (such as shape, size, and

tions cause changes in the flavor, color, tenderness, and

color) as well as chemical constituents of the sample by

appearance of red meat (Xiong et al., 2014). As such, de-

spectral analysis (ElMasry et al., 2012a). Hyperspectral

tection of chemical attributes is important to ensure con-

imaging provides three-dimensional information on the

sumer health and satisfaction as well as reduce the meat

sample. Three-dimensional hyperspectral cubes, i.e., (x, y,

industry’s economic losses. Reflectance hyperspectral im-

λ), where λ is the wavelength, can be acquired using point- aging in the Vis/NIR range (900 to 1700 nm) has been used

scan, line-scan, and area-scan methods. A hyperspectral in conjunction with chemometrics models for determination

imaging system typically consists of a CCD camera (or an of different quality attributes, such as water, protein, and fat

InGaAs camera for the NIR region), an imaging spectro- content in beef of different breeds (ElMasry et al., 2013);

scope, a light source, a sample holding platform, a comput- color, pH, and tenderness of fresh beef (ElMasry et al.,

er, and related software (Leiva-Valenzuela et al., 2014; Qin 2012a); and tenderness of 14-day cooked beef (Naganathan

et al., 2013; Siedliska et al., 2014; Tao and Peng, 2014). et al., 2008b). These studies reported the use of partial least

Figure 2 is a schematic of a hyperspectral imaging system. squares regression (PLSR) to reduce the high dimensionali-

Hyperspectral imaging systems can be categorized into ty of the hyperspectral data. Naganathan et al. (2008a) re-

Vis/NIR imaging (He et al., 2014; Pierna et al., 2012; Yu et ported that a PLSR model could classify beef as tender,

al., 2014), fluorescence imaging (Cho et al., 2013; Davis et intermediate, and tough with classification accuracy of 78%

al., 2014; Noh et al., 2007), and Raman imaging (Qin et al., based on slice shearing force (SSF) analysis. The authors

2011). The light source in a hyperspectral system can be a

defined SSF ≤ 205.8 N as tender meat, SSF between 205.8

point source (Erkinbaev et al., 2014; Tao and Peng, 2014)

and 254.8 N as intermediate, and SSF > 254.8 N as tough

or a diffuse source (Dai et al., 2014; Everard et al., 2014;

meat. In a similar study, a hyperspectral imaging system

Lu and Ariana, 2013; Siedliska et al., 2014). The infor-

(496 to 1036 nm) was used to measure the tenderness of

mation obtained from hyperspectral image acquisition is

beef (Cluff et al., 2008). The authors reported fitting the

used for detecting internal as well as external qualities of

optical scattering profiles obtained from the hyperspectral

the sample.

58(5): 1371-1386 1373

images using a modified Lorentzian function. Stepwise nation (Tao and Peng, 2014). Similarly, a combination of

regression was used to identify the feature wavelengths to Lorentzian and Gompertz functions was used to extract

predict the tenderness of the samples in terms of WBSF useful information from hyperspectral imaging data to pre-

with a correlation coefficient (R) of 0.67. dict total viable count (TVC) in pork stored at 10°C for 1 to

Application of a time series hyperspectral imaging sys- 15 days after slaughter (Tao and Peng, 2015). PCA was

tem (380 to 1700 nm) was reported to determine the water reported to extract characteristic pictures from hyperspec-

distribution in beef during dehydration using principal tral images in the spectral range of 430 to 960 nm to evalu-

component analysis (PCA) (Wu et al., 2013). A successive ate TVC in pork meat 24 h postmortem (Huang et al.,

projections algorithm (SPA) was used to select the feature 2013b).

wavelengths, and a multi-linear regression (MLR) model Freshness is an essential index of meat quality and di-

was developed to predict the water content in beef slices rectly influences storage and logistics. TVB-N, pH, and

with a coefficient of determination of 0.95. color are the most important factors for meat freshness as-

sessment. Among the three parameters, TVB-N is the most

Lamb

important (Li et al., 2011c; Zhang et al., 2012). Hyperspec-

Potential application of near-infrared (NIR) hyperspec-

tral imaging has been used with different chemometrics

tral imaging has been reported for determination of the

modeling methods to predict TVB-N in pork as a measure

chemical composition (water, fat, and protein content) of

of its freshness (Chen et al., 2013; Li et al., 2015). Li et al.

lamb meat (Kamruzzaman et al., 2012a; Pu et al., 2014).

(2013) developed a multispectral imaging system to collect

Kamruzzaman et al. (2013) reported a PLSR method to

scattering images of pork samples and selected the wave-

detect water, fat, and protein content in lamb with coeffi-

lengths of 517, 550, 560, 580, 600, 760, 810, and 910 nm

cients of determination of 0.88, 0.88, and 0.63, respective-

for TVB-N modeling.

ly. Feature wavelengths were extracted for the PLSR mod-

Salting is used to produce high-quality of meat and meat

eling to reduce the computational complexity, thus reduc-

products by avoiding (or delaying) microbial growth and

ing the time for detection of each sample. Pu et al. (2014)

thus increasing the product’s stability. Meat quality can

used a combination of uninformative variable elimination

deteriorate during salting, resulting in nutritional loss and

(UVA) and successive projections algorithm (SPA) to ex-

texture problems. Moisture content has been considered a

tract feature wavelengths (eight different feature wave-

major source of growth for microbial organisms in meat,

lengths for fat, protein, and water). From the feature wave-

and it is considered a key parameter affecting meat texture

lengths, seven wavelengths were selected to develop MLR

(Ruiz-Ramirez et al., 2005; Serra et al., 2005). Microbial

models. The MLR models were reported to have correla-

growth or texture loss influences the shelf life of salted

tion coefficients of calibration of 0.95, 0.80, and 0.91 for

meat and meat products. Hyperspectral reflectance spectra

fat, protein, and water content, respectively. The UVA and

(RS), absorbance spectra (AS), and Kubelka-Munk spectra

SPA method greatly reduced the high-dimension hyper-

(KMS) in the wavelength range of 1000 to 2500 nm were

spectral data, and the MLR model had superior results

reported for prediction of moisture content in pork slices

compared to PLSR. Similarly, hyperspectral imaging (900

during salting (Liu et al., 2014b). The same researchers

to 1700 nm) was applied for non-destructive determination

reported application of hyperspectral imaging in the spec-

of the tenderness of lamb meat (Kamruzzaman et al.,

tral range of 400 to 100 nm to predict color and pH in salt-

2012b). The same group of researchers also reported the

ed pork (Liu et al., 2014a).

potential use of NIR hyperspectral imaging (900 to

To reduce the hyperspectral data, hyperspectral imaging

1700 nm) for discrimination of three different lamb mus-

can be implemented in a multispectral imaging mode. Ma

cles, i.e., semitendinosus (ST), longissimus dorsi (LD), and

et al. (2014) used a multispectral imaging system in the

psoas major (PM), of Charollais breed (Kamruzzaman et

Vis/NIR region to determine the aerobic plate count (APC)

al., 2011).

in cooked pork sausages. A novel algorithm was reported

Pork for feature selection to develop linear and non-linear re-

Similar to beef and lamb, hyperspectral imaging has gression of L*, a*, and b* color from multispectral images

been extensively used for non-destructive determination of of pork samples (Sharifzadeh et al., 2014).

the quality attributes of pork. A hyperspectral imaging sys-

Other Meats

tem in the NIR region (900 to 1700 nm) was used to deter-

Measuring the quality attributes of poultry meat is im-

mine the protein, moisture, and fat content in intact and

portant to ensure public health and consumer satisfaction

minced pork (Barbin et al., 2013). A PLSR model was de-

and standardize the meat processing procedure for econom-

veloped to select a few feature wavelengths from the high-

ic benefit. As with red meats, hyperspectral imaging has

dimension hyperspectral data. The authors reported coeffi-

been reported for detection of different quality attributes of

cients of determination of 0.92, 0.88, and 0.94 for protein,

poultry meat.

fat, and moisture content, respectively, which are better

Hyperspectral imaging in the visible range of 400 to

than those for beef (ElMasry et al., 2013) and lamb

1000 nm was reported for measuring the springiness of

(Kamruzzaman et al., 2012a).

fresh chicken meat (Xiong et al., 2015). Hyperspectral im-

A novel method including the modified Gompertz func-

aging has also been reported to determine the quality of

tion was used to extract scattering characteristics of pork

chicken meat during processing. Fusion of hyperspectral

from spatially resolved hyperspectral images (400 to

transmittance and reflectance imaging was reported for

1100 nm) for evaluation of tenderness and E. coli contami-

1374 TRANSACTIONS OF THE ASABE

detection of embedded bone fragments in chicken fillets ment of protein content. That study also reported the poten-

(Yoon et al., 2008). In discussing the potential industrial tial of Vis/NIR spectroscopy with a first-derivative data

application of the imaging technology, the authors men- processing algorithm for simultaneous detection of various

tioned that variation in meat thickness influenced the imag- quality parameters. A Vis/NIR spectroscopy system with a

ing results, which can be overcome by better control of conveyor belt for on-line detection of meat quality showed

meat slicing thickness. encouraging results for application in industry (Prieto et al.,

Feng et al. (2013) applied a hyperspectral imaging sys- 2009a). Vis/NIR reflectance spectroscopy in the spectral

tem in reflectance mode for detection of Enterobacteri- range of 350 to 1800 nm was used to measure color, cook-

acease on chicken fillets. The authors reported the devel- ing loss, texture, and sensory characteristics of beef.

opment of a bacterial prediction model by PLSR using full Vis/NIR spectroscopy (350 to 2500 nm) was also used for

wavelengths in the spectral region of 430 to 1450 nm and on-line classification of beef carcasses (cows, bulls, steers,

achieved a correlation coefficient of determination (R2) and heifers) based on ultimate pH (measured 48 h postmor-

greater than 0.82. Similarly, Feng and Sun (2013a) used tem) (Reis and Rosenvold, 2014). The authors reported that

line scanning hyperspectral imaging (900 to 1700 nm) for optical spectroscopy with PLS can replace existing meth-

rapid and non-destructive determination of Pseudomonas ods of detection in on-line classification of beef carcasses.

counts in chicken breast fillets. The hyperspectral images In addition to measurement of quality attributes, studies

were correlated with the actual counts of Pseudomonas by have also been performed to classify meat based on fresh-

PLSR. The authors also reported determination of TVC in ness. Infrared spectroscopy has proven to be a potential tool

chicken breast fillets using NIR hyperspectral imaging in for detecting beef spoilage by micro-organisms (Argyri et

the spectral range of 910 to 1700 nm (Feng and Sun., al., 2010; Ellis et al., 2004; Kodogiannis et al., 2014). Fou-

2013b). In addition to detection of chicken quality attrib- rier transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy (4000 to

utes, research has been reported on prediction of moisture, 400 cm-1) and machine learning algorithms were used to

color, and pH in cooked turkey ham by NIR hyperspectral detect beef fillet spoilage in two different storage condi-

imaging in the spectral range of 900 to 1700 nm (Iqbal et tions (chill temperature and abuse temperature) (Argyri et

al., 2013). The research showed the ability of NIR hyper- al., 2010). The artificial neural network algorithm correctly

spectral imaging to detect different quality attributes simul- classified fresh samples with 91.7% accuracy, semi-fresh

taneously. samples with 81.2% accuracy, and spoiled samples with

94.1% accuracy. The detection accuracy for semi-fresh

QUALITY INSPECTION BY SPECTROSCOPIC METHODS samples was lower than that for the other two classes of

Spectroscopic methods such as visual and NIR, Raman samples. It was reasoned that the fresh samples and spoiled

spectroscopy, and x-ray are often reported for rapid and samples that were close to semi-fresh samples, and vice

non-destructive detection of different quality attributes of versa, reduced the accuracy of the algorithm.

meat. Spectroscopic methods generally use point scanning. Vis/NIR spectroscopy has also been used for measuring

Different from line scanning or area scanning, point scan- different indexes in cattle fed sunflower seed or flaxseed

ning can be used for more homogenous samples. Acquisi- (Prieto et al., 2014). The authors reported the application of

tion of spectral signals from a few representative points on NIR spectroscopy in the range of 400 to 2498 nm for ana-

the sample creates a greater chance for variance in the lyzing the meat’s chemical composition, quality attributes,

measurement accuracy and stability if the sample is are and fatty acid content. Infrared technology was also used to

chemically or physically uneven. However, for homoge- measure beef quality during processing (Perisic et al.,

nous samples, spectroscopic methods can be reliable, accu- 2013). Excessive intake of sodium has a negative influence

rate, rapid, and simpler compared to other methods. on human health, and attempts have been made to replace

NaCl (major source of sodium in meat) with other salts.

Beef

However, this might influence the quality attributes of

Vis/NIR spectroscopy has been applied for detection of

meat. FTIR and Vis/NIR measurements were made of the

multiple quality attributes of beef, such as chemical com-

effects of KCl and MgSo4, as substitutes for NaCl, on the

position (Prieto et al., 2006), characterization of beef mus-

quality of beef samples. MgSo4 was acceptable when it was

cle on the basis of cooked WBSF (Xia et al., 2007), and

applied at a mixture ratio of 1:3. Morsy and Sun (2013)

measurement of quality attributes of ground and intact beef

reported on the application of NIR spectroscopy with PLSR

in terms of pH, color (L*, a*, b*), aging loss, cooking loss,

to detect fresh and frozen-thawed minced beef adulterated

and WBSF (Marchi et al., 2013). While these studies re-

with pork, fat trimmings, and offal. The authors reported

ported the potential of Vis/NIR for measurement of beef

high accuracy (coefficients of determination >0.9 for all

quality attributes, the measurement accuracy was generally

three adulterations) for minced beef samples; however, the

not satisfactory because scanning a single point at a time on

detection accuracy was considerably lower for frozen-

each sample can cause poor performance of the model.

thawed samples.

Sample homogeneity is a crucial factor for development of

efficient chemometrics models using spectroscopic meth- Lamb

ods. Ripoll et al. (2008) reported good measurement results A hand-held Raman-based optical instrument was used

with NIR reflectance spectroscopy for tenderness (R2 = for measurement of shear force in lamb m. longissimus

0.98), myoglobin (R2 = 91), WHC (R2 = 0.82), and WBSF lumborum (Fowler et al., 2014a). A 671 nm laser source

(R2 = 0.7). However, the correlation was low for measure- was used in the optical device to measure the shear force by

58(5): 1371-1386 1375

correlating the Raman spectral signal with the value meas- cal changes in fresh minced pork meat (Papadopoulou et

ured by traditional methods. Poor correlation was reported al., 2011). A handheld Raman prototype with a 671 nm

for predicting the shear force in lamb muscle. The same microsystem diode laser was reported for in situ detection

researchers reported using Raman spectroscopy for predict- of microbial spoilage in pork meat (Sowoidnich et al.,

ing the tenderness of fresh lamb meat samples, but the re- 2010). A novel technology based on mid-Fourier transform

sult was not promising (Fowler et al., 2014b). NIR reflec- infrared spectroscopy (MID-FTIR) was reported for detec-

tance spectroscopy was used in a correlation between the tion of Trichinellaspiralis infection in pig muscles (Gomez-

spectral signal and sensory parameters that are directly re- De-Anda et al., 2012). Spectroscopy in the spectral range of

lated to the eating quality of lamb meat (Andres et al., 4000 to 650 cm-1 with attenuated total reflectance and soft

2007). The authors reported R2 values of less than 0.40 for independent modeling of class analogy was used to classify

predicting the texture, juiciness, flavor, abnormal flavor, the samples with 100% accuracy for both recognition and

and overall quality when correlating the spectral signal with rejection based on sample infection.

the scores from a tasting panel. However, the authors re- NIR spectroscopy in the spectral range of 1150 to

ported significant increases in the prediction accuracy for 2250 nm was used to characterize absorption, scattering,

the best and worst samples. This shows that the NIR spec- and angular scattering distribution of pig adipose tissues for

tral signal is informative for detecting quality attributes of non-destructive analysis of intact adipose tissue for indus-

lamb meat. The same study reported R2 values of 0.84 and trial application (Zamora-Rojas et al., 2013). In the late

0.67 for predicting intramuscular fat and water content, 1990s, NIR reflectance (900 to 1800 nm) was used for

respectively, in lamb meat. measurement of WHC and drip loss in fresh pork with cor-

NIR spectroscopy has been used extensively for meas- relations greater than 80% (Forrest et al., 2000). Three

urement of chemical constituents in lamb meat, and prom- years later, Pedersen et al. (2003) reported that the infrared

ising results have been reported. NIR reflectance spectros- region from 1800 to 900 cm-1 contained the best predictive

copy was used to measure chemical constituents such as information for measuring WHC of pork meat. The authors

ash, dry matter, crude protein, and fat in mutton (Viljoen et used infrared spectroscopy with PLSR to measure WHC in

al., 2007) with correlation coefficients of 0.97, 0.96, 1.00, pork with a correlation coefficient of 0.89. The results were

and 1.00, respectively. The same method was used to de- confirmed in on-line measurement of pork WHC using FT-

termine mineral contents in lamb meat samples, with corre- IR spectroscopy.

lation coefficients ranging from 0.86 (for Zn and K) to 0.92 An effort was made to develop an on-line optical spec-

for Mg, but low accuracies were found for Cu, B, Mn, Ca, troscopy system to measure quality attributes of fresh pork

and Al. Guy et al. (2011) applied NIR reflectance spectros- (Liao et al., 2010). A conveyor belt combined with Vis/NIR

copy for detection of fatty acids in ground lamb meat sam- spectroscopy (350 to 1100 nm) was designed to acquire

ples and intact unground samples. The results showed that spectral signals from fresh pork to measure the intramuscu-

NIR reflectance spectroscopy predicted the fatty acid con- lar fat, protein, water, pH, and shear force rapidly and non-

tent in ground meat more accurately than in unground meat. destructively. Later, Liao et al. (2012) developed another

The differences in the degree of homogeneity of the ground on-line system for non-destructive measurement of pH val-

and unground meat samples could be one reason for the ues in fresh pork using Vis/NIR spectroscopy.

difference in accuracy.

Other Meats

Sun et al. (2012) reported a novel method for detecting

Extensive studies have been reported on applications of

the quality of lamb meat. The authors used NIR reflectance

optical spectroscopic methods for detection of different

spectroscopy in the spectral range of 950 to 1650 nm to

quality and safety attributes of poultry. NIR spectroscopy

classify lamb meat according to geographic origin and also

has been used extensively for detection of fatty acid content

predicted δ13C and δ15N with high accuracy. Dian et al.

in different parts of chicken meat with encouraging results;

(2008) classified lamb carcasses based on feeding method

however, the method did not perform well when measure-

for quality detection using Vis/NIR spectroscopy in the

ments were carried out in real-time (Marchi et al., 2012;

spectral range of 400 to 2500 nm.

Riovanto et al., 2012; Zhou et al., 2012). Short-wavelength

Pork NIR spectroscopy (400 to 1000 nm) was reported for detec-

NIR spectroscopy has shown promising results for de- tion of moisture content, water activity, pH, TVB-N, ATP

tection of chemical constituents such as fat, moisture, and breakdown compounds, and mesophilic bacteria, which

protein in pork (Perez-Marin et al., 2009; Zamora-Rojas et were regarded as the useful parameters for prediction of

al., 2013). A study of non-destructive measurement of pork chicken freshness (Grau et al., 2011). Like red meats, poul-

freshness with storage time was reported using FT-NIR try is also susceptible to bacterial spoilage. Studies have

spectroscopy in the spectral range of 10,000 to 4000 cm-1 been reported on determining the spoilage of chicken meat

(Chen et al., 2011). Different mathematical models, such as during aerobic storage using NIR and fluorescence spec-

linear discriminant analysis (LDA), back-propagation arti- troscopy (Sahar and Dufour, 2014; Sahar et al., 2011). A

ficial neural network (BP-ANN), and k-nearest neighbor recent study showed the potential of NIR spectroscopy (400

(kNN), were used to develop prediction models, among to 2500 nm) for quality assessment of chicken meat based

which BP-ANN was reported to have superior results over on pale, soft, and exudative (PSE), L*, pH, and WHC

the other models. FTIR spectroscopy in the spectral range (Barbin et al., 2015). Other spectroscopic methods such as

of 4000 to 650 cm-1 was reported for monitoring biochemi- Raman (excitation by 785 nm) also showed promising re-

1376 TRANSACTIONS OF THE ASABE

sults for establishing spectral fingerprints to monitor the vision and image processing have been reported in the lit-

WHC of broilers based on growth rate (Phongpa-Ngain et erature for detection of different quality attributes of beef.

al., 2014). Examples include prediction of shrinkage of ellipsoid beef

joints (Zheng et al., 2007); prediction of color, marbling,

QUALITY INSPECTION BY MACHINE VISION and surface texture (Jackman et al., 2008); measurement of

AND IMAGE PROCESSING texture features to classify beef as tough or tender (Li et al.,

Machine vision has proven to be effective for quality de- 2001); prediction of skeletal maturity based on cartilage

tection of agricultural products (Dowlati et al., 2012; ossification in the thoracic vertebrae (Hatem et al., 2003);

ElMasry et al., 2012c; Khazaei et al., 2013; Kurtulmus and measurement of CIE L*, a*, b*, hue angle, and chroma

Kavdir, 2014; Wang et al., 2011). Machine vision methods (Larrain et al., 2008); automatic segmentation of the longis-

have been widely used for surface quality detection of dif- simus dorsi muscle and marbling (Jackman et al., 2009);

ferent meats and meat products. However, due to the lim- prediction of percentage surface metmyoglobin on fresh

ited information in the digital images provided by machine beef, which causes wide variation in surface color (Demos

vision, this method cannot be used in chemometrics model- et al., 1996); and classification of fresh and stained meat

ing to predict the chemical composition and internal quality samples based on marbling in the longissimus thoracis

attributes of meat. muscle (Pena et al., 2013).

Beef Pork

Machine vision has been used extensively for measuring Machine vision and image processing have been exten-

color, fat, and other physical parameters of meat. Studies sively reported for detecting different physical quality at-

have reported developments of novel hardware for machine tributes, such as marbling, back fat thickness, color, texture

vision systems and software algorithms for image pro- features, and intramuscular fat content. Digital image anal-

cessing to extract useful information for non-destructive ysis was used for quantitative description of marbling fat

and rapid detection of physical quality attributes of meat. A and its relationship with intramuscular fat content and shear

machine vision system was developed using a color digital force variation in pork (Faucitano et al., 2005). RGB-based

camera to measure the fat color of beef for quality grading digital color analysis was applied for prediction of marbling

(Chen et al., 2010). An image processing algorithm was in pork (Huang et al., 2013a). The region of interest ac-

reported for prediction of intramuscular fat content in beef quired from the sample image was used for extraction of

m. longissimus dorsi (Du et al., 2008). The image pro- marbling using a wide line detector and gray-level co-

cessing algorithm initially removed noise in the original occurrence matrix. Prediction models were developed indi-

image, followed by automatic segmentation of the image vidually using red, green, and blue channels as well as us-

into regions of interest using kernel fuzzy c-means cluster- ing the RGB three-channel with a color wheel (or an RGB

ing. Finally, intramuscular fat content was extracted from LED array). The prediction model developed based on the

the image for development of a prediction model. Similar- green channel had high correlation coefficients (Rc and Rv

ly, Chen and Qin (2008) reported a machine vision and of 0.94) for predicting pork marbling. Machine vision and

image processing method for segmentation of marbling. digital image processing have also been used for measure-

Because simple RGB digital images do not contain spec- ment of other physical attributes, such as lean and fat com-

tral information for chemometrics modeling, a different position based on video images (Jia et al., 2010).

approach to digital image analysis was reported to deter- Jackman et al. (2010) reported the use of color and

mine moisture content in cooked beef by machine vision wavelet texture features for classification of pork and tur-

(Zheng et al., 2006). The authors reported extraction of key ham based on quality grades. Du and Sun (2006) re-

color features (means and standard deviations) in terms of ported a computer vision method to detect pores and poros-

RGB and HSI (hue, saturation, and intensity). The color in ity in pork ham in an area between 6.73 × 10-3 and 2.02 ×

the sample images was correlated to the moisture content 10-1 mm2. Chmiel et al. (2011b) reported on distinguishing

obtained by chemical analysis, which showed encouraging PSE (pale, soft, exudative) and RFN (reddish pink, firm,

correlation coefficients of 0.56 (for models built by PLSR) normal) in m. longissimus dorsi using color components

and 0.45 (for models built by a neural network algorithm). (lightness parameters L*). Similar studies have been report-

The study showed a potential for machine vision and image ed on classification of pre-sliced ham (based on color) and

processing for detection of chemical contents in meat. its relationship with consumer responses (Iqbal et al.,

Research on the relationship of color to chemical, physi- 2010); classification of pre-sliced pork ham using neural

cal, and biological changes can enhance the accuracy of networks (Valous et al., 2010); changes in the color, chem-

image processing for rapid and non-destructive detection of ical composition, and texture of m. longissimus dorsi in

meat quality attributes. Application of a digital camera with pigs due to management system (Zapotoczny et al., 2014);

an auxiliary lighting system was reported for prediction of evaluation of pork carcass color (Lu et al., 2000); and

troponin-T degradation in beef longissimus using texture measurement of pork belly fat (Uttaro and Zawadski,

features from color images (Sun et al., 2014). The authors 2010). To reduce the difficulty of meat quality classifica-

reported the use of stepwise and support vector machine tion due to high variability and complex color distribution,

(SVM) methods to classify the samples based on degrada- Valous et al. (2009) calibrated the color obtained by a

tion, with satisfactory accuracy. computer vision system using a polynomial transform pro-

A wide range of methods and applications in machine cedure and the transform proposed by the sRGB standard.

58(5): 1371-1386 1377

The authors applied the algorithm to evaluate the color and spectroscopic and machine vision methods. Hyperspectral

presence of pores and fat-connective tissue in pre-sliced imaging has the flexibility of functioning as a spectroscopic

pork, turkey, and chicken ham with encouraging accuracy. method, a machine vision method, or a combination of

both. However, hyperspectral imaging has so far had lim-

Lamb

ited applications in industrial processing because hyper-

Although machine vision and image analysis have prov-

spectral images contain huge quantities of data, which re-

en useful for quantifying the quality of different meat and

duces the detection speed (Cho et al., 2007). Cho et al.

meat products, little research has been reported on meas-

(2007) proposed an innovative method of implementing a

urement of lamb quality attributes. Geometric and texture

hyperspectral imaging system in multispectral imaging

analyses of images obtained from a color digital camera

mode, which enabled fast, online detection without sacrific-

were used to predict cooked lamb tenderness (Chandraratne

ing accuracy. A number of studies have reported on the use

et al., 2006a). Similarly, a machine vision system consist-

of multispectral methods for detection of meat quality at-

ing of three CCD digital color cameras was reported for

tributes. Studies have also been reported on applications of

grading lamb carcasses (Chandraratne et al., 2006b). The

multispectral methods independently.

acquired images included lean area, marbling, subcutane-

Variation in light intensity in the sample is another

ous fat, intramuscular fat, bone, and background. The au-

shortcoming that influences the stability of optical methods

thors reported that image analysis using geometric and tex-

in practical applications. The light intensity is reduced at

ture features is a useful tool for lamb classification. The

the edges of samples, and in the hidden areas of carcasses,

same researchers also reported on statistical and neural

which influences optical signal acquisition. When uneven

network analyses of the extracted image features for classi-

samples are illuminated, large differences in light intensity

fication of lamb carcasses (Chandraratne et al., 2007).

occur at different surface locations of the same sample,

Other Meats which influence the measurement accuracy by the system.

Machine vision and image analysis have been used for A band ratio algorithm can reduce the variation in light

detection of fat content in chicken and turkey (Chmiel et intensity (Park et al., 2006).

al., 2011a), to estimate live weight of broilers for monitor- For rapid, non-destructive, real-time application in in-

ing growth (Mollah et al., 2010), and for inspection of dustrial processing, research must focus on simultaneous

poultry carcasses for wholesomeness (Chao et al., 2000, detection of different quality attributes by the same system.

2007). Implementing multiples systems, each dedicated to detec-

tion of a particular quality attribute, is expensive and tech-

nically challenging. However, only a few studies have re-

CHALLENGES AND FUTURE WORK ported simultaneous detection of multiple quality attributes

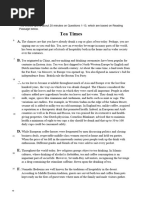

Table 1 summarizes research studies that have been re- by the same system (Tao et al., 2012). Studies are thus

ported since 2003 on hyperspectral imaging, Vis/NIR spec- needed on the relationships between optical measurements

troscopy, and machine vision methods for quality detection and the different physical and chemical properties of meat

of meat and meat products. Vis/NIR has proven to be a to help develop algorithms for rapid prediction of multiple

potential tool for non-destructive quality detection of meat quality attributes by the same system.

and meat products. Although a number of studies have Although many studies have reported using different op-

shown that Vis/NIR is useful for assessing physical, chemi- tical instruments and statistical analysis methods, the num-

cal, biological, and sensory quality attributes of meat and ber of samples used in many reported studies is often quite

meat products, few studies on industrial applications have small, which creates a higher probability of overfitting for

been reported. The accuracy, repeatability, and stability of the calibration model. Future studies should thus use larger

optical methods are highly dependent on the surrounding numbers of samples to develop and test calibration models

environment. For example, lighting can be a limiting factor for improved model performance.

for optical methods because the environmental conditions Practical applications of optical technology are needed

in the laboratory are highly controlled, which may not be for quality detection of processed meat and for detection of

the case in industrial settings. The meat samples in a pro- adulterants in raw and processed meat. Except for a few

cessing line often vary greatly in size and quality, which studies, most reported studies have focused on fresh meat.

can affect online measurement accuracy. The distance be- Quality detection of processed meat in packaging and dur-

tween the sample and the optical sensor must also be con- ing storage and transport is important for quality control.

sidered for ensuring precise measurements. An uneven Several studies have reported that packaging conditions

sample surface is another major source of optical measure- have a direct influence on meat quality and shelf life. High-

ment error. Development of conveyor systems equipped pressure processing and modified-atmosphere packaging

with distance sensors to maintain a constant distance be- were reported to influence microorganism activity and pH

tween the sample and the optical sensor can help reduce in pork products, which in turn influenced the flavor of the

measurement error, thus enabling optical system applica- meat (Olmo et al., 2014). Precise packaging conditions are

tions in industry. required to maintain the shelf life and quality of meat and

Hyperspectral imaging has proven to be superior to meat products. Sade et al. (2013) found different types of

spectroscopy and machine vision because it acquires in- enterobacteria in meat and poultry samples packaged in

formation that is far beyond what can be obtained by both modified-atmosphere packaging. Lee (2010) reported seri-

ous effects on the quality and safety of meat products due

1378 TRANSACTIONS OF THE ASABE

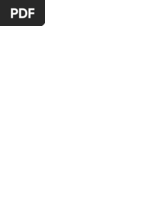

Table 1. Application of optical technologies for meat quality detection.[a]

Quality Optical Wavelength Analysis Correlation

Meat Attribute Technology Range Method Coefficient Reference

Beef Protein content HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.86 ElMasry et al. (2013)

Spectroscopy 1000-1800 nm PLSR 0.98 Su et al. (2014)

Moisture content HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.89 ElMasry et al. (2013)

HSI 1000-2500 nm MLR 0.92 Liu et al. (2014b)

Spectroscopy 1000-1800 nm PLSR 0.99 Su et al. (2014)

Marbling HSI 400-1100 nm - 0.92 Li et al. (2011b)

MV - - Satisfactory Chen and Qin (2008)

MV - - R = 1 and R = 0.96 Jackman et al. (2009)

Fat content HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.84 ElMasry et al. (2013)

HSI 1000-2300 nm PLSR 0.90 Kobayashi et al. (2010)

Spectroscopy 1000-1800 nm PLSR 0.99 Su et al. (2014)

Scanner 760-1040 nm - - Wold et al. (2011)

Micro-organisms HSI 400-1100 nm MLR 0.96 for TVC Peng et al. (2009)

MSI 405-970 nm PLS-DA, >80%, Panagou et al. (2014)

PLSR 0.78-0.86

Tenderness HSI 400-1100 nm MLR 0.91 Wu et al. (2012)

HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.83 ElMasry et al. (2012a)

HSI 400-1000 nm PCA 96.4% Naganathan et al. (2008a)

HSI 922-1739 nm LDA 83.3% (tough), 75% (tender) Cluff et al. (2013)

Color HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.88 (L*), 0.81 (b*) ElMasry et al. (2012a)

pH HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.73 ElMasry et al. (2012a)

Spectroscopy 350-2500 nm PLSR 90% Reis and Rosenvold (2014)

WHC HSI 910-1700 nm PLSR 0.89 (full spectrum), ElMasry et al. (2011)

0.87 (selected wavelengths)

Pork Protein content Spectroscopy 350-1100 nm PLSR 0.75 Liao et al. (2010)

HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.92 Barbin et al. (2013)

Moisture content Spectroscopy 350-1100 nm PLSR 0.79 Liao et al. (2010)

HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.87 Barbin et al. (2013)

Marbling Computer image analysis - - - Faucitano et al. (2005)

Fat content Spectroscopy 350-1100 nm PLSR 0.76 Liao et al. (2010)

HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.95 Barbin et al. (2013)

Micro-organisms Fluorescence 200-900 nm PLSR >0.90 (plate count) Oto et al. (2013)

FT-NIR spectroscopy 10,000-4000 cm-1 SI-PLSR 0.80 (for TVB-N) Cai et al. (2011)

Vis/NIR camera 550-1000 nm PLSR 0.89 (for TVB-N using Wang et al. (2013)

selected wavelengths)

Tenderness FT-NIR spectroscopy 10,000-4000 cm-1 SI-PLSR 0.70 Cai et al. (2011)

HSI and MV - PLSR 0.75 Barbin et al. (2013)

Color Spectroscopy 400-2500 nm M-PLRS Poor Cozzolino et al. (2003)

HSI 400-1000 nm ANN 0.86 Qiao et al. (2007)

pH Spectroscopy 350-1100 nm PLSR 0.82 Liao et al. (2010)

HSI 400-1000 nm ANN 0.55 Qiao et al. (2007)

WHC Spectroscopy 400-2500 nm PLSR <0.62 Maja et al. (2010)

Lamb Protein content HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.63 Kamruzzaman et al. (2012a)

Fat content HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.88 Kamruzzaman et al. (2012a)

Spectroscopy 400-2498 nm - 0.84 Andres et al. (2007)

Moisture content HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.88 Kamruzzaman et al. (2012a)

Spectroscopy 400-2498 nm - 0.67 Andres et al. (2007)

pH HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.65 Andres et al. (2007)

HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.65 Kamruzzaman et al. (2012b)

Color HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.91 Kamruzzaman et al. (2012b)

Tenderness HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.84 (WBSF), Kamruzzaman et al. (2013)

0.69 (sensory tenderness)

Drip loss HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.77 Kamruzzaman et al. (2012b)

Poultry Micro-organisms HSI 930-450 nm PLSR >0.89 Feng et al. (2013)

in chicken HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.97 (for TVC) Feng and Sun (2013b)

Ingesta HSI 400-1000 nm Image 89% (ingesta), Yoon et al. (2011)

processing 98% (fecal material)

Moisture in turkey ham HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.88 Iqbal et al. (2013)

Color in turkey ham HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.74 Iqbal et al. (2013)

pH in turkey ham HSI 900-1700 nm PLSR 0.81 Iqbal et al. (2013)

Adulterants In minced beef FTIR spectroscopy 4000-650 cm-1 PLSR 0.99 Meza-Marquez et al. (2010)

In fresh and frozen- Spectroscopy 400-2500 nm PLS-DA 100% Morsy and Sun (2013)

thawed minced beef

[a]

HSI = hyperspectral imaging, MV = machine vision, MSI = multispectral imaging, PLSR = partial least squares regression, and M-PLSR = modified PLSR.

to manipulation of the packaging material. Packaged meat spoilage during storage and transport. Hence, there is an

products are susceptible to contamination before packaging urgent need for technology that can monitor the quality

and due to the packaging material, and are thus prone to attributes of packaged meat products.

58(5): 1371-1386 1379

Meat adulteration not only causes serious damage to the Argyri, A. A., Panagou, E. Z., Tarantilis, P. A., Polysiou, M., &

reputation of the meat industry but also influences consum- Nychas, G.-J. E. (2010). Rapid qualitative and quantitative

er health and perceptions. Certain meats and meat products detection of beef fillets spoilage based on Fourier transform

that are accepted by consumers of a certain community infrared spectroscopy data and artificial neural networks.

Sensors Actuators B, 145(1), 146-154.

may not be acceptable to another community. Current http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2009.11.052.

methods for detecting meat adulterants rely on HPLC, gas Argyri, A. A., Doulgeraki, A. I., Blana, V. A., Pangou, E. Z., &

chromatography, and liquid chromatography for measuring Nychas, G.-J. E. (2011). Potential of a simple HPLC-based

fatty acid composition, histidine dipeptides, and proteins approach for the identification of the spoilage status of minced

(Ashoor et al., 1988; Carnegie et al., 1983; Verbeke and beef stored at various temperatures and packaging systems. Intl.

Brabander, 1995). These measurement methods are com- J. Food Microbiol., 150(1), 25-33.

plex and cannot be used for routine inspection. It is thus http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ijfoodmicro.2011.07.010.

important to develop non-destructive technology to monitor Ashoor, S. H., Monte, W. G., & Stiles, P. G. (1988). Liquid

meat adulterants, in addition to meat quality detection. Re- chromatographic identification of meats. J. Assoc. Official Anal.

Chem., 71(2), 397-403.

search has been reported on detection of pork, fat trimming, Balasubramanian, S., Panigrahi, S., Logue, C. M., Gu, H., &

and offal adulterants in fresh and frozen-thawed minced Marchello, M. (2009). Neural networks-integrated metal oxide-

beef using NIR spectroscopy (Morsy and Sun, 2013); on based artificial olfactory system for meat spoilage identification.

turkey adulterants in minced beef using UV-VIS, NIR, and J. Food Eng., 91(1), 91-98.

MIR spectroscopy (Alamprese et al., 2013); and on horse http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2008.08.008.

meat in mixtures with other meats by protein content using Barbin, D. F., ElMasry, G., Sun, D.-W., & Allen, P. (2013). Non-

Raman spectroscopy (Zajac et al., 2014). However, none of destructive determination of chemical composition in intact and

these methods has been reported for practical use, and chal- minced pork using near-infrared hyperspectral imaging. Food

lenges remain in the development of reliable methods for Chem., 138(2-3), 1162-1171.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.11.120.

industrial application. Databases of the chemical properties Barbin, D. F., Kaminishikawahara, C. M., Soares, A. L., Mizubuti,

of adulterants that are suitable for use by optical systems I. Y., Grespan, M., Shimokomaki, M., & Hirooka, E. Y. (2015).

can be useful for industrial applications, as meat adulterants Prediction of chicken quality attributes by near-infrared

are often identified by their chemical properties. spectroscopy. Food Chem., 168, 554-560.

Finally, challenges remain in reducing the size of optical http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.07.101.

systems, developing hardware suitable for use in industrial Boselli, E., Pacetti, D., Curzi, F., & Frega, N. G. (2008).

environments, and designing control software with an easy- Determination of phospholipid molecular species in pork meat

to-use graphical user interface (GUI). Most hyperspectral by high-performance liquid chromatography tandem mass

imaging, multispectral imaging, and Raman spectroscopic spectrometry and evaporative light scattering detection. Meat

Sci., 78(3), 305-313.

systems are bulky and are limited to laboratory use. Com- http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.06.017.

pact hardware that is suitable for industrial use will be at- Cai, J., Chen, Q., Wan, X., & Zhao, J. (2011). Determination of

tractive to the meat industry. Studies have reported on the total volatile basic nitrogen (TVB-N) content and Warner-

detection of meat quality attributes using hand-held optical Bratzler shear force (WBSF) in pork using Fourier transform

devices and conveyor belt optical systems (Guo et al., near-infrared (FT-NIR) spectroscopy. Food Chem., 126(1),

2012a, 2012b; Wan et al., 2014; Wang et al., 2012; Yang et 1354-1360. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2010.11.098.

al., 2012; Zhao et al., 2012). More studies on such Carnegie, P. R., Illic, M. Z., Etheridge, M. O., & Collins, M. G.

handheld devices are needed under different experimental (1983). Improved high-performance liquid chromatography

conditions for different types of samples (i.e., different method for analysis of histidine dipeptides anserine, carnosine,

and balenine present in fresh meat. J. Chromatog., 26(1), 153-

sample sizes, breeds, and slaughterhouses) to evaluate their 157. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0021-9673(01)87933-4.

potential for industrial application. Chandraratne, M. R., Samarasinghe, S., Kulasiri, D., &

Bickerstaffe, R. (2006a). Prediction of lamb tenderness using

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS image surface texture features. J. Food Eng., 77(3), 492-499.

The authors wish to thank the Special Fund for Agro- http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.06.063.

Scientific Research in the Public Interest (Project No. Chandraratne, M. R., Kulasiri, D., Frampton, C., Samarasinghe, S.,

201003008) of China for providing funding support for this & Bickerstaffe, R. (2006b). Prediction of lamb carcass grades

research. using features extracted from lamb chop images. J. Food Eng.,

74(1), 116-124.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.02.012.

Chandraratne, M. R., Kulasiri, D., & Samarasinghe, S. (2007).

REFERENCES Classification of lamb carcass using machine vision:

Alamprese, C., Casale, M., Sinelli, N., Lanteri, S., & Casiraghi, E. Comparison of statistical and neural network analyses. J. Food

(2013). Detection of minced beef adulteration with turkey meat Eng., 82(1), 26-34.

by UV-vis, NIR, and MIR spectroscopy. LWT Food Sci. Tech., http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2007.01.003.

53(1), 225-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.lwt.2013.01.027. Chao, K., Park, B., Chen, Y. R., Hruschka, W. R., & Wheaton, F.

Andres, S., Murray, I., Navajas, E. A., Fisher, A. V., Lambe, N. R., W. (2000). Design of a dual-camera system for poultry carcasses

& Bunger, L. (2007). Prediction of sensory characteristics of inspection. Appl. Eng. Agric., 16(5), 581-587.

lamb meat samples by near-infrared reflectance spectroscopy. http://dx.doi.org/10.13031/2013.5291.

Meat Sci., 76(3), 509-516. Chao, K., Yang, C.-C., Chen, Y.-R., Kim, M. S., & Chan, D. E.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2007.01.011. (2007). Fast line-scan imaging system for broiler carcass

1380 TRANSACTIONS OF THE ASABE

inspection. Sensory Instrum. Food Qual., 1, 62-71. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2007.07.026.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11694-007-9008-y. Davis, R. W., Jones, H. D. T., Collins, A. M., Ricken, J. B.,

Chen, K., & Qin, C. (2008). Segmentation of beef marbling based Sinclair, M. B., Timlin, J. A., & Singh, S. (2014). Label-free

vision threshold. Comput. Elec. Agric., 62(2), 223-230. measurement of algal triacylglyceride production using

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2008.01.002. fluorescence hyperspectral imaging. Algal Res., 5, 181-189.

Chen, K., Sun, X., Qin, C., & Tang, X. (2010). Color grading of http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.algal.2013.11.010.

beef fat by using computer vision and support vector machine. Demos, B. P., Gerrard, D. E., Gao, X., Tan, J., & Mandigo, R. W.

Comput. Elec. Agric., 70(1), 27-32. (1996). Utilization of image processing to quantitate surface

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2009.08.006. metmyglobin on fresh beef. Meat Sci., 43(3-4), 265-274.

Chen, Q., Cai, J., Wan, X., & Zhao, J. (2011). Application of http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/0309-1740(95)00061-5.

linear/non-linear classification algorithms in discrimination of Dian, P. H. M., Andueza, D., Jestin, M., Prado, I. N., & Prache, S.

pork storage time using Fourier transform near-infrared (FT- (2008). Comparision of visible and near-infrared reflectance

NIR) spectroscopy. LWT Food Sci. Tech., 44(10), 2053-2058. spectroscopy to discriminate between pasture-fed and

Chen, Q., Zhang, Y., Zhao, J., & Hui, Z. (2013). Non-destructive concentrate-fed lamb carcasses. Meat Sci., 80(4), 1157-1164.

measurement of total viable basic nitrogen (TVB-N) content in http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.05.009.

salted pork in jelly using a hyperspectral imaging technique Dowlati, M., Mohtasebi, S. S., & Guardia, M. D. L. (2012).

combined with efficient hypercube processing algorithms. Anal. Application of machine-vision technique to fish-quality

Methods, 5(22), 6382-6388. assessment. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem., 40, 168-179.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1039/c3ay40436f. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.trac.2012.07.011.

Chmiel, M., Slowinski, M., & Dasiewicz, K. (2011a). Application Du, C.-J., & Sun, D.-W. (2006). Automatic measurement of pores

of computer vision system for estimation of fat content in and porosity in pork ham and their correlation with processing

poultry meat. Food Control, 22(8), 1424-1427. time, water content, and texture. Meat Sci., 72(2), 294-302.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2011.03.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2005.07.016.

Chmiel, M., Slowinski, M., & Dasiewicz, K. (2011b). Lightness of Du, C.-J., & Sun, D.-W. (2008). Multi-classification of pizza using

the color measured by computer image analysis as a factor for computer vision and support vector machine. J. Food Eng.,

assessing the quality of pork meat. Meat Sci., 88(3), 566-570. 86(2), 234-242.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2011.02.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2007.10.001.

Cho, B.-K., Chen, Y.-R., & Kim, M. S. (2007). Multispectral Du, C.-J., Sun, D.-W., Jackman, P., & Allen, P. (2008).

detection of organic residue on poultry processing plant Development of hybrid image processing algorithm for

equipment based on hyperspectral reflectance imaging automatic evaluation of intramuscular fat content in beef m.

technique. Comput. Elec. Agric., 57(2), 177-189. longissimus dorsi. Meat Sci., 80(4), 1231-1237.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2007.03.008. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.05.036.

Cho, B.-K., Kim, M. S., Baek, I.-S., Kim, D.-Y., Lee, W.-H., Kim, Ellis, D. I., Broadhurst, D., & Goodacre, R. (2004). Rapid and

J., Bae. H., & Kim, Y.-S. (2013). Detection of cuticle defects on qualitative detection of the microbial spoilage of beef by Fourier

cherry tomatoes using hyperspectral fluorescence imagery. transform infrared spectroscopy and machine learning. Anal.

Postharvest Biol. Tech., 76, 40-49. Chim. Acta, 514(2), 193-201.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.postharvbio.2012.09.002. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.aca.2004.03.060.

Clariana, M., Gratacos-Cubarsi, M., Hortos, M., Garcia-Regueiro, J. ElMasry, G., Sun, D.-W., & Allen, P. (2011). Non-destructive

A., & Castellari, M. (2010). Analysis of seven purines and determination of water-holding capacity in fresh beef by using

pyrimidines in pork meat products by ultra-high performance NIR hyperspectral imaging. Food Res. Intl., 44(9), 2624-2633.

liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry. J. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2011.05.001.

Chromatog. A, 1217(6), 4294-4299. ElMasry, G., Sun, D.-W., & Allen, P. (2012a). Near-infrared

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.chroma.2010.04.033. hyperspectral imaging for predicting color, pH, and tenderness

Cluff, K., Naganathan, G., Subbiah, J., Lu, R., Calkins, C. R., & of fresh beef. J. Food Eng., 110(1), 127-140.

Samal, A. (2008). Optical scattering in beef steak to predict http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2011.11.028.

tenderness using hyperspectral imaging in the vis-NIR region. ElMasry, G., Barbin, D. F., Sun, D.-W., & Allen, P. (2012b). Meat

Sensory Instrum. Food Qual., 2(3), 189-196. quality evaluation by hyperspectral imaging technique: An

http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11694-008-9052-2. overview. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr., 52(8), 689-711.

Cluff, K., Naganathan, G. K., Subbiah, J., Samal, A., & Calkins, C. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/10408398.2010.507908.

R. (2013). Optical scattering with hyperspectral imaging to ElMasry, G., Cubero, S., Molto, E., & Blasco, J. (2012c). In-line

classify longissimus dorsi muscle based on beef tenderness sorting of irregular potatoes by using automated computer-based

using multivariate modeling. Meat Sci., 95(1), 42-50. machine vision system. J. Food Eng., 112(1-2), 60-68.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2013.04.014. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2012.03.027.

Cozzolino, D., Barlocco, N., Vadell, A., Ballesteros, F., & Gallieta, ElMasry, G., Sun, D.-W., & Allen, P. (2013). Chemical-free

G. (2003). The use of visible and near-infrared reflectance assessment and mapping of major constituents in beef using

spectroscopy to predict colour on both intact and homogenised hyperspectral imaging. J. Food Eng., 117(2), 235-245.

pork muscle. LWT Food Sci.Tech., 36(2), 195-202. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2013.02.016.

Dai, Q., Cheng, J.-H., Sun, D.-W., & Zeng, X.-A. (2014). Potential Erkinbaev, C., Herremans, E., Trong, N. N. D., Jakubczyk, E.,

of hyperspectral imaging for non-invasive determination of Verbpven, P., Nocolai, B., & Saeys, W. (2014). Contactless and

mechanical properties of prawn (Metapenaeus ensis). J. Food non-destructive differentiation of microstructures of sugar foams

Eng., 136, 64-72. by hyperspectral scatter imaging. Innov. Food Sci. Emerg. Tech.,

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.03.013. 24, 131-137. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.ifset.2013.08.007.

Damez, J.-L., Clerjon, S., Abouelkaram, S., & Lepetit, J. (2008). Everard, C. D., Kim, M. S., & Lee, H. (2014). A comparison of

Beef meat electrical impedance spectroscopy and anisotropy hyperspectral reflectance and fluorescence imaging techniques

sensing for non-invasive early assessment of meat spoilage. J. for detection of contaminants on spinach leaves. J. Food Eng.,

Food Eng., 85(1), 116-122. 143, 139-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2014.06.042.

58(5): 1371-1386 1381

Faucitano, L., Huff, P., Teuscher, F., Gariepy, C., & Wegner, J. Hatem, I., Tan, J., & Gerrard, D. E. (2003). Determination of animal

(2005). Application of computer image analysis to measure pork skeletal maturity by image processing. Meat Sci., 65(3), 999-

marbling characteristics. Meat Sci., 69(3), 537-543. 1004. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0309-1740(02)00318-2.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2004.09.010. Haugen, J.-E., Lundby, F., Wold, J. P., & Veberg, A. (2006).

Feng, W., Yao, X., Zhu, Y., Tian, Y. C., & Cao, W. X. (2008). Detection of rancidity in freeze-stored turkey meat using a

Monitoring leaf nitrogen status with hyperspectral reflectance in commercial gas-sensor array system. Sensors Actuators B,

wheat. European J. Agron., 28(3), 394-404. 116(1-2), 78-84. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.snb.2005.12.060.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.eja.2007.11.005. He, H.-J., Wu, D., & Sun, D.-W. (2014). Rapid and non-destructive

Feng, Y.-Z., & Sun, D.-W. (2013a). Near-infrared hyperspectral determination of drip loss and pH distribution in farmed Atlantic

imaging in tandem with partial least squares regression and salmon (Salmo salar) fillets using visible and near-infrared (vis-

genetics algorithm for non-destructive determination and NIR) hyperspectral imaging. Food Chem., 156(1), 394-401.

visualization of Pseudomonas loads in chicken fillets. Talanta, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2014.01.118.

109, 74-83. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2013.01.057. Huang, H., Liu, L., Ngadi, M. O., & Gariepy, C. (2013a). Prediction

Feng, Y.-Z., & Sun, D.-W. (2013b). Determination of total visible of pork marbling scores using pattern analysis techniques. Food

count (TVC) in chicken breast fillets by near-infrared Control, 31(1), 224-229.

hyperspectral imaging and spectroscopic transforms. Talanta, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodcont.2012.09.034.

105, 244-249. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.talanta.2012.11.042. Huang, L., Zhao, J., Chen, Q., & Zhang, Y. (2013b). Rapid

Feng, Y.-Z., ElMasry, G., Sun, D.-W., Scannell, A. G. M., Walsh, detection of total viable count (TVC) in pork meat by

D., & Morcy, N. (2013). Near-infrared hyperspectral imaging hyperspectral imaging. Food Res. Intl., 54(1), 821-828.

and partial least squares regression for rapid and reagentless http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodres.2013.08.011.

determination of Enterobacteriaceae on chicken fillet. Food Iqbal, A., Valous, N. A., Mendoza, F., Sun, D.-W., & Allen, P.

Chem., 138(2-3), 1829-1836. (2010). Classification of pre-sliced pork and turkey ham

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.foodchem.2012.11.040. qualities based on image colour and textural features and their

Forrest, J. C., Morgan, M. T., Borggaard, C., Rasmussen, A. J., relationships with consumer responses. Meat Sci., 84(3), 455-

Jespersen, B. L., & Andersen, J. R. (2000). Development of 465. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.09.016.

technology for the early post-mortem prediction of water- Iqbal, A., Sun, D.-W., & Allen, P. (2013). Prediction of moisture,

holding capacity and drip loss in fresh pork. Meat Sci., 55(1), color, and pH in cooked, pre-sliced turkey hams by NIR

115-122. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0309-1740(99)00133-3. hyperspectral imaging system. J. Food Eng., 117(1), 42-51.

Fowler, S. M., Schmidt, H., Ven, R. V. D., Wynn, P., & Hopkins, http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2013.02.001.

D. L. (2014a). Raman spectroscopy compared against traditional Jackman, P., Sun, D.-W., Du, C.-J., Allen, P., & Downey, G.

predictors of shear force in lamb m. longissimus lumborum. (2008). Prediction of beef eating quality from color, marbling,

Meat Sci., 98(4), 652-656. and wavelet texture features. Meat Sci., 80(4), 1273-1281.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2014.06.042. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2008.06.001.

Fowler, S. M., Schmidt, H., Ven, R. V. D., Wynn, P., & Hopkins, Jackman, P., Sun, D.-W., & Allen, P. (2009). Automatic selection

D. L. (2014b). Predicting tenderness of fresh ovine of beef longissimus dorsi muscle and marbling by an adaptable

semimembranosus using Raman spectroscopy. Meat Sci., 97(4), algorithm. Meat Sci., 83(2), 187-194.

597-601. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2014.02.018. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.03.010.

Gomez, A. H., He, Y., & Pereira, A. G. (2006). Non-destructive Jackman, P., Sun, D.-W., Allen, P., Valous, N. A., Mendoza, F., &

measurement of acidity, soluble solids, and firmness of Satsuma Ward, P. (2010). Identification of important image features for

mandarin using vis/NIR spectroscopy technique. J. Food Eng., pork and turkey ham classification using color and wavelet

77(2), 313-319. texture features and genetic selection. Meat Sci., 84(4), 711-717.

http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jfoodeng.2005.06.036. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.meatsci.2009.10.030.

Gomez-De-Anda, F., Dorantes-Alvarez, L., Gallardo-Velazquez, T., Jamshidi, B., Minaei, S., Mohajerani, E., & Ghassemian, H. (2012).

Osorio-Revilla, G., Calderon-Dominguez, G., Labat, P. M., & Reflectance vis/NIR spectroscopy for nondestructive taste

de-la-Rosa-Arana, J.-L. (2012). Determination of Trichinella characterization of valencia oranges. Comput. Elec. Agric., 85,

spiralis in pig muscles using mid-Fourier transform infrared 64-69. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.compag.2012.03.008.

spectroscopy (mid-FTIR) with attenuated total reflectance Ji, W., Zhao, D., Cheng, G., Xu, B., Zhang, Y., & Wang, J. (2012).