AI and the 2024 United States Election: It’s ‘We The People,’ Not AI We Need to Worry About

All images were generated by Open AI’s DALLE-2. AI was not used to create the analysis.

Just after I finished my talk on AI and the 2024 U.S. Elections at the TechTalk Summits Impact event in St. Petersburg, Florida, I walked back to my room and flipped on the television to CNN, where Jake Tapper was about to discuss AI and the 2024 election (transcript here). The recent President Biden robocall deep fake urging Democratic voters to sit out the New Hampshire primary brought the potential threats of widespread AI-generated misinformation to the forefront (see Fake Joe Biden robocall tells New Hampshire Democrats not to vote Tuesday from NBC News). AI has become its own topic in the 2024 election cycle.

The worry is that AI will sow doubt, misrepresent the truth, and tilt the election outcome. Consensus, however, suggests that misinformation will not significantly impact the presidential election. Most people have already decided who they plan to vote for—and most people click on legitimately reported sources that offer fact-checked sources. However, AI-generated misinformation from the 2024 election and other sources of fraudulent facts may change people’s perceptions and practices regarding information over time.

Well-crafted misinformation will make truth harder to identify, creating the need for increased diligence among the electorate to verify sources and fact-check assertions. It is unclear how Americans will react. A 2023 Pew study found that 65% of Americans often feel exhausted when thinking about politics. No AI productivity promise is likely to eliminate politics as a source of stress.

The CNN story covered two points I made in my TechTalk Summits closing keynote on AI and the 2024 Election:

- Misdirection on campaigns isn’t new; it’s just using new tools.

- News coverage will make AI a more important issue to election choices than it will actually turn out to be.

False information about elections is nothing new. Mailers that offer misleading candidate endorsements have existed for a long time. Misrepresentations of voting records and other information about candidates are also common.

But on the Internet, most people seek information from legitimate sources. A 2021 study from Brooking’s NYU Center on Social Media and Politics found that 89% of news URLs viewed on Facebook were from credible sources.

While AI will increase the scale of misrepresentation, it will not necessarily escalate the consumption of misinformation. More people, however, many of them with few of the resources associated with a traditional political campaign, will be able to generate misinformation and spread it quickly using AI and social media tools. Further, the rise of AI may improve the perceived “quality” of the misrepresentation, meaning that it may make it appear more authentic.

We will not know until after the election if emergent sources of misinformation drove engagement or changed people’s minds.

Who will AI-based misinformation target?

Three groups will prove the most likely to face onslaughts of AI-generated material:

Voters. Voters will likely face misinformation and disinformation on candidate positions, perhaps about their histories that range from birth to voting records as well as details about the election, such as voting locations or times.

Contributors. Phishing attacks will likely target people pretending to be campaigns to gather personal information and steal funds via fake donation transactions.

Campaign and election offices. Denial-of-service attacks may take on a new flavor as AI bombardments of requests for information flood campaigns and election offices, distracting volunteers and paid staff from doing their real work as they attempt to discern which requests are legitimate.

Authentic uses of AI in elections

AI is not without legitimate campaign use. While some areas listed below may remain controversial, leveraging AI can help candidates and issue-based campaigns share their beliefs, experiences, and positions more effectively with target audiences, just as it assists other marketing efforts.

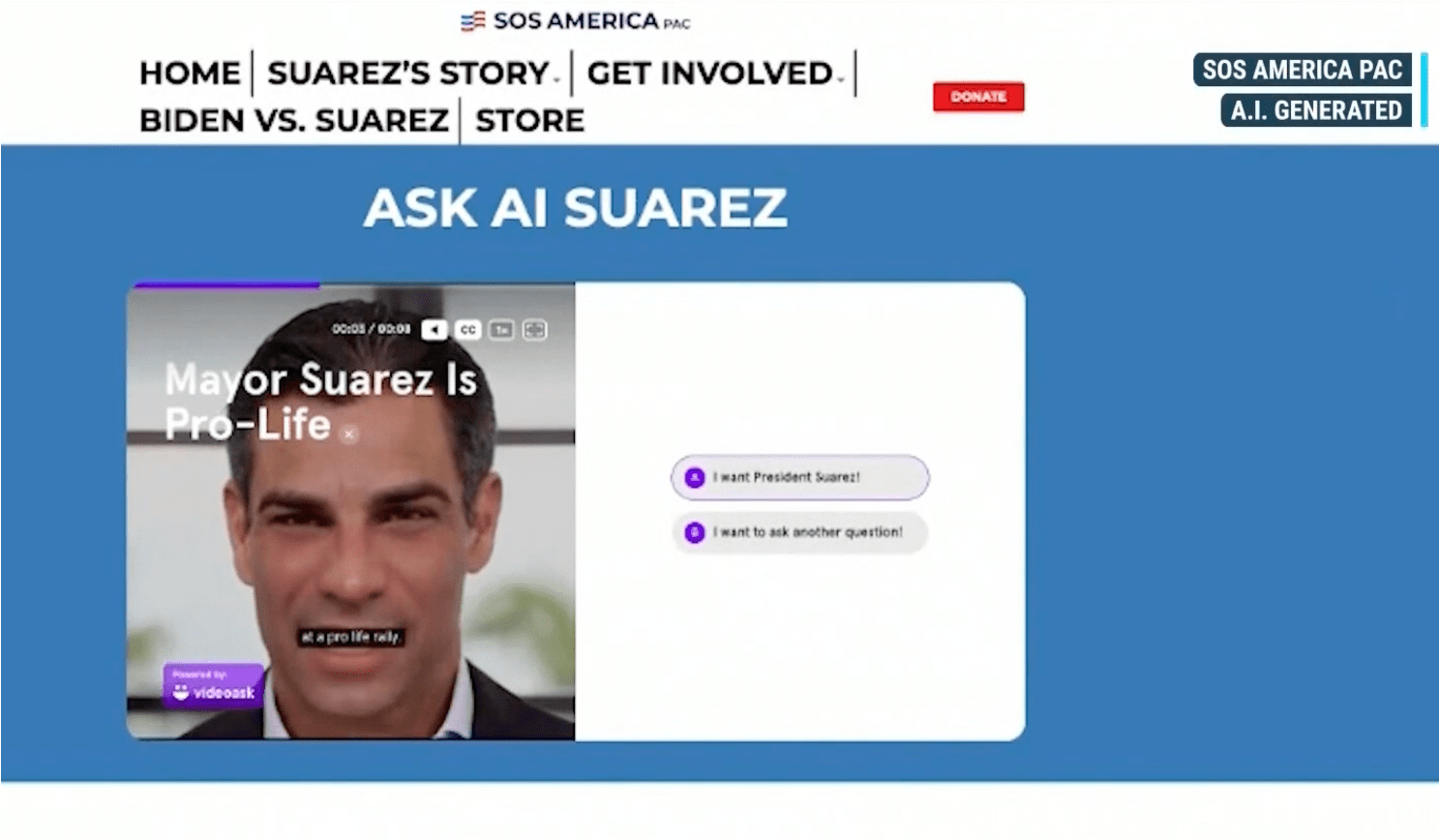

Virtual candidate. The SOS America PAC already floated a virtual candidate with “Ask AI Suarez,” an attempt to expand awareness of Miami’s Mayor Francis Suarez’s positions. The virtual candidate was not officially part of the campaign and has since ceased to interact with would-be voters, but it is likely an experiment that will be repeated multiple times, if not in this election, then in future contests.

Virtual positioning via chatbots. Large Language Models will transform how people explore candidate position papers and other content. There will likely be chatbots on positions that serve up the answers rather than trying to be too cute with personas or avatars. However, some well-financed campaigns may take constituency interaction to higher levels.

Content and communications. Campaigns will employ AI throughout the content creation process, from drafting e-mails to AI-composed campaign videos. As long as the content is authentic (or at least not inauthentic), states truthful positions, communicates actual beliefs, and uses verifiable facts, campaign workers will legitimately use AI to edit, hone, compile, draft, or offer feedback on campaign content.

Voter data analysis and targeting. Using AI for classifying voter data adds a layer to already sophisticated business intelligence employed by campaigns for better understanding voter propensities toward issues, willingness to donate, and their ability to get to the polls.

Robo-Calling. While the FCC has banned AI-originated calls that impersonate celebrities or politicians (see the FCC Makes AI-Generated Voices in Robocalls Illegal page here) as illegal, other calls that clearly state their artificial origins upfront and avoid any pretense of deception will be used for legitimate purposes such as polling, fund-raising, voluntary information gathering, or get-out-the-vote efforts, should all be considered legitimate use.

Translation. New York City Mayor Eric Adams cannot speak Mandarin, as this AP story states in analyzing the reaction to his team’s recent outreach using computer-generated translation. Although rules may develop early to discourage this practice, automated translation should be considered a legitimate use of AI over the long term. People would have little issue with a Mandarin-speaking city worker or campaign volunteer reaching out to the community for input or information dissemination.

In the case of constituency communications, there is little difference between human translation and AI translation when it comes to the intent to communicate information within a diverse population, with the caveat that the message clearly states that it is artificial. It would also behoove those disseminating AI-generated translations to add, at least for now, that some of the translations may be overly formal or inaccurate.

Elected officials who personally speak only one language should be able to explore technology that encourages dialog with their constituencies. Some “watchdogs,” like the Surveillance Technology Oversight Project, would serve their cause better if they focused on making such calls useful and productive rather than deriding the experimentation.

Translation may eventually prove a legitimate use of AI as a concept, but that does not mean individuals will find it an acceptable practice at the interpersonal level. How campaigns position and execute AI translation will prove essential in determining its acceptance by those receiving such outreach.

Translations may move from push (calls) to pull (on-demand translation of audio, video, or text), and that choice will further define the role AI translation plays in elections.

What should people expect?

No new misinformation or disinformation approaches will likely appear during the 2024 cycle. Doctored photos, falsified quotes, statements out of context, donation scams, and misrepresenting voting information are not new. Deep fakes aren’t new either; AI offers new tools to those practicing deception.

AI also makes creating the artifacts of deception easier and enables the practice at a broader scale. For the 2024 election, misinformation stories should focus on scale rather than the nuance of AI-generated falsities.

For the 2024 elections, areas to watch include:

- False claims that call election results into question.

- Attacks that descend at the last minute may not give journalists or others time to contest and verify the veracity of claims.

- AI’s impact on the election as news will simultaneously distract from more pertinent stories, inform those seeking to identify false information, and perhaps even embolden those inspired by the successes of other bad actors.

- The nation-state, state-sponsored, or extra-national criminals injecting false information into the U.S. election dialog.

While misinformation can appear through any channel, citizens should be particularly wary of content on TikTok, as its algorithm is more likely to surface material from outside of trusted networks than other social media platforms.

AI and the 2024 United States Election

Areas Where AI Might be Used to Create Misinformation

Misinformation

- Misrepresentation of other candidates

- False images

- False content

- Content that looks like it comes from the election office

- Chatbots and robo-calling

- AI-generated attack ads

- Voter suppression: Tangential misinformation to keep people away from the polls such as false calendar entries and dates and incorrect location information.

- Misinformation from nation-states and other external sources

- Imitation candidates

- Spoofing official election information channels

Harassment

Open Records Requests to campaigns and election offices aimed at driving busy work rather than campaigning or governing.

Phishing

People pretending to be an official and asking for private information from individuals or from an election office or campaign.

People pretending to be with a campaign and soliciting donations.

The 2024 U.S. election will be a test bed for AI’s role in this content-heavy human activity. It will test how people and organizations react to the speed of content creation, the information it carries, and its ability to engage already attention-challenged citizens.

This election cycle will also challenge information organization business models. The false equity of accessible, crowd-sourced information will come up against traditional news services with reduced staffs of journalists and fact-checkers. The failure of traditional subscription models has gutted newspaper and magazine staff nationwide. Will the citizenry of the United States reconsider its relationship to a free press?

Remember that many of those creating false information do so purposefully. The deceivers, too, will be gauging the impact of their efforts against other investments. They will want to see if AI delivers the impacts they seek. Whether chaos or a particular result, if AI fails to deliver results to information manipulators in 2024, those insights may have much to say about AI’s future in more legitimate contexts.

Wagging the Dog’s Long Tail

The long-term impact of AI on U.S. elections will not be the increasingly hard-to-discern AI-generated images and content; it will be the scale at which such content becomes available. AI models may be influenced by massive amounts of false information, skewing their weights and making them more likely to provide false information to users.

AI and the 2024 United States Election: The Problems with Regulating AI

There are two primary issues with AI regulation. First, regulation will likely lag or misalign with current technology. AI’s rampant rise and continued evolution make it hard for regulators to enact laws or rules that are more than generalizations. Without specifics, bad actors can always claim exceptions from laws with exploits specifically designed to avoid the stated legal provisions.

Second, laws are local. Bad nation-state actors, or those otherwise operating outside national boundaries, are often not subject to the local laws and will most certainly not recognize their jurisdiction. In the case of totalitarian governments, U.S. laws may directly conflict with their local policy, implicitly or explicitly, as they seek any means to disrupt orderly life and governance in the United States.

The more serious threat is the loss of trust in accurate information, leading to the liar’s dividend, where the sowing of distrust can call out truth, facts, and evidence, claiming falseness and having others, at minimum, doubt its legitimacy and, at worst, believing the truth to be a lie.

The AI-based tools or approaches that arise during the 2024 election will likely result in an AI arms race against misinformation that will not be limited to politics. Companies and their products, non-profit institutions, causes, and other entities will also be the victims of misinformation. The AI arms race will pit those creating various forms of attack against those attempting to thwart them. Tools will seek to identify AI-generated falsities, while others will discover ways to skirt discovery.

Recommendations for Reducing AI’s Impact on U.S. Elections

Pre-bunking. As discussed on NPR’s All Things Considered in October of 2022, pre-bunking seeks out those areas where misinformation could cause harm—harm to individuals, institutions, or organizations—and attempts to build resilience in the truth before false information spreads. Pre-bunking attempts to inoculate listeners or viewers from false information. Google tried it during the 2020 election with near-term resulting in short-term improved awareness of misinformation tactics like scapegoating or false choice presentation (see more on the Cambridge University/Google study here: Psychological inoculation improves resilience against misinformation on social media.)

Those attempting pre-bunking should look for the opposite impact, as those pushing false information might label it indoctrination rather than inoculation.

Content marking. Other forms of misinformation remediation rely on content suppliers to label sources, offer disclosures, or watermark content. AI-generated material would also be labeled. Those approaches, however, often fail because false information producers counterfeit legitimizing markings or will leverage AI tools without marking technology, such as standalone, open-source language models that don’t incorporate AI identification technology.

Search providers focus on verified information. Google, Meta, Microsoft and others will continue to attempt to focus on legitimate sources of information. Big tech will pit their technological prowess and content curation capabilities against those injecting false information as indexable content. The results will likely be mixed, leaving consumers to choose what they click on and what they believe.

Accountability. Not all responsible AI or AI ethics policies include accountability. The FCC’s recent robocall ruling includes provisions for fines and number blocking. The Telephone Consumer Protection Act already provides consequences for unauthorized telemarketing calls. My phone still rings, often from a number with a name that has nothing to do with the call on the other end.

Average robocall scams are hard to police, and even with the profile of the recent fake President Biden robocall in New Hampshire, finding the perpetrators proves difficult, as will prosecuting them. Adam Schiff proposes cracking down on social media companies (see Rollcall’s ‘Social media should be accountable for ‘deepfake content,’ intelligence experts say’). This approach places accountability on the publisher rather than the perpetrator. While companies should avoid knowingly publishing harmful or misleading content, they will likely not be up to the task of policing all content on their platforms, any more than telecommunications or cities can police telephone poles and light standards plastered and stapled with posters, flyers with tear-offs tabs, and advertisements.

Rules or regulations must include clear consequences that make responsibility more enticing than choosing an illegal action.

Reconsider Super PACs. The advent of the Super PAC following the Citizens United ruling by the U.S. Supreme Court opened the door to many well-funded organizations and individuals contributing large sums of money to elections.

Super-PACs don’t fall under the same restrictions as political campaigns, but their often parallel or adjacent investments become part of the narrative, influencing votes through content and activities that many traditional campaigns cannot afford. The SOS investment in AI Saurez is an example of an AI experiment, supporting a candidate’s ambitions without a direct tie to the candidate or their campaign.

If scale is the concern, regulations that curtail misleading narratives from super-PACs, regardless of the underlying technology, may prove more effective at reducing misinformation than regulatory efforts targeting AI.

AI and the 2024 United States Election: Uncertainty

Much of the impact of AI, misinformation, and disinformation remains unknown and, therefore, uncertain. Citizens will likely seek remediation for misinformation and its effects through the courts and perhaps via more surreptitious means. Forecasts can speculate, but U.S. citizens will not know the volume, scale, or impact of misinformation until after the election, perhaps long after. The dialog around AI and the election will likely encourage more experimentation than discourage it.

As AI-generated content becomes commonplace, it will cease to be a story and will perhaps, over time, become just another attribute of campaigns, talked about with little more fanfare or trepidation than well-funded get-out-the-vote efforts.

Scenario planners must pay vigilant attention to the impact of AI and the elections themselves. The shift of some uncertainties toward certainty will trigger the necessity to reimagine what might be in light of emerging realities.

Ethics, AI and the 2024 United States election

AI will not compose false information about candidates. It will not prompt itself to generate images of candidates in compromising positions. It will not envision deep fake audio that guides citizens to act contrary to the real candidate’s—and perhaps their own—beliefs.

People will choose to employ AI to create misleading content and false images, audio, and video. In many cases, the laws and practices around campaigns already forbid such deception—but the tools have changed. And the new tools place these capabilities into more hands, increasing the chances of misinformation arising from almost anywhere.

This post does not describe misinformation that honest Americans would not already find morally reprehensible, regardless of regulatory frameworks or new laws. The FCC need not have published its ruling on falsifying the image or voice of politicians or celebrities in service to deception. Everyone, even the deceivers, knows such an activity is wrong.

Using powerful tools, whether computer algorithms or weapons, is also a choice. The AI community decided to offer all of their tools with little consideration for implication, save for those features restricted by paywalls that filter not on intent but on the ability to buy the services.

The 2024 U.S. election will be a referendum on the citizens of the United States, much more so than on generative AI. People’s choices will have a longer tail than any ephemeral content generated by an AI.

On Wednesday, November 6, 2024, the citizens of the United States can start reflecting on the ramifications of AI—how it was wielded, how well they weathered the onslaught of information, true and false, and if they think the country made the best moral choices for its future, the most expedient ones, or if they were manipulated into some other set of choices that will create new challenges for our democracy.

The United States Constitution begins with We the People of the United States. We may not be responsible for the actions of those who use AI, disingenuous politicians, or criminals, but the Constitution holds us accountable for Justice in the continued pursuit of our more perfect Union.

For more serious insights on AI, click here.

Do you have thoughts or comments on AI and the 2024 United States Election? If so, please like this post, ask a question or leave a comment.

Leave a Reply