Commons:Lucrări derivate

Numeroase lucrări de creaţie sunt lucrări derivate, dar în majoritatea cazurilor, nu se pot revendica drepturi de autor asupra acestora din diverse cauze. De exemplu, pentru fotografii, printre excepţii se numără cele care nu reprezintă lucrări de creaţie, lucrări utilitare, excepţiile date de libertatea de panoramă, şi aşa mai departe. Totuşi, în toate celelalte cazuri, doar deţinătorul drepturilor de autor poate autoriza lucrări derivate. Aceste lucrări sunt fotografii ale unor sculpturi, păpuşi şi alte lucrări aflate sub incidenţa drepturilor de autor. Acelaşi principiu se aplică şi altor lucrări: nu puteţi face un film pe baza unei cărţi citite de dumneavoastră fără permisiunea autorului acesteia, deoarece aceasta constituie lucrare derivată.

In either case, unless the underlying work is in the public domain or there is evidence that the underlying work has been freely licensed for reuse (for example, under an appropriate Creative Commons license), the original creator of the work must explicitly authorize the copy/ derivative work before it can be uploaded to Commons.

In summary: you cannot trace someone else's copyrighted creative drawing and upload that tracing to Commons under a new, free license because a tracing is a copy without new creative content; likewise, you cannot make a movie version of a book you just read without the permission of the author, even if you added substantial creative new material to the storyline, because the movie requires the original book author's permission— if such permission were obtained, however, the movie would likely then be considered a derivative work entitled to its own novel copyright protection. "Derivative", in this sense, does not simply mean "derived from", it means, "derived from and including new creative content which is entitled to a new copyright."

Ce este o lucrare derivată?

Lucrările derivate, conform Legii Dreptului de Autor din SUA din 1976, secţiunea 101, sunt definite după cum urmează:[1]

- „O lucrare derivată este o lucrare realizată pe baza uneia sau mai multor lucrări existente anterior, cum ar fi o traducere, un aranjament muzical, o dramatizare, o versiune cinematografică, o ficţionalizare, o înregistrare audio, o reproducere de artă, o variantă rezumată, sau orice altă formă în care o lucrare poate fi reîncapsulată, transformată sau adaptată. O lucrare ce constă din reviziuni editoriale, adnotări, elaborări, sau alte modificări şi care, ca întreg, reprezintă o lucrare originală, constituie lucrare derivată”.

Pe scurt, orice transfer de lucrare de creaţie sub incidenţa drepturilor de autor într-o nouă formă este lucrare derivată, ca şi toate celelalte modificări al căror rezultat este o nouă lucrare originală. Cine poate crea o astfel de lucrare derivată? Vedeţi Legea Dreptului de Autor din SUA din 1976, secţiunea 106:

- „Deţinătorul dreptului de autor sub acest titlu are dreptul exclusiv de a face şi de a autoriza următoarele: (...) (2) pregătirea de lucrări derivate pe baza lucrării sale”.

Spre deosebire de o copie exactă sau de o mică variaţie a lucrării (de ex., aceeaşi carte cu un titlu diferit), care nu creează un nou drept de autor, o lucrare derivată creează un drept de autor asupra tuturor aspectelor originale din noua versiune. Astfel, de exemplu, creatorul cărţii The Annotated Hobbit deţine dreptul de autor asupra tuturor notelor şi comentariilor pe care le-a scris, dar nu şi asupra textului original al cărţii The Hobbit care este inclusă în aceasta. Dreptul de autor iniţial este încă în vigoare. Persoana care deţine dreptul de autor asupra a, să zicem, o păpuşă Darth Vader sau o statuie de Picasso, are dreptul exclusiv de a crea lucrări derivate. Aceasta include fotografii ale lucrării, deoarece (după cum au arătat deciziile instanţelor) acesta este un aspect al lucrării deţinătorului dreptului de autor pe care acesta ar putea dori să-l exploateze comercial.

Likewise, the corporation that holds the copyright to Darth Vader (i.e., Walt Disney) has the exclusive right to create or authorize any derivative works of that character, including photographs or drawings of him which portray him in novel and creative ways, since (as court decisions put it) that is one aspect of the copyright holder's work that they might want to exploit commercially. In the same manner, anyone can make a movie based on The Bible, and may make their own movie called "The Ten Commandments" based on the Biblical chapter Exodus, but may not make a new version of the 1956 film, "The Ten Commandments", even with substantial new creative input, without getting permission of Paramount Pictures (the copyright holder).

Dacă fac o poză a unui obiect cu aparatul meu, deţin dreptul de autor al imaginii rezultate. Nu pot să o eliberez eu sub orice licenţă vreau? De ce trebuie să-mi pun problema altor deţinători de drepturi de autor?

Când face o fotografie cu un personaj dintr-un desen animat aflat sub incidenţa drepturilor de autor de pe un tricou şi acesta este principalul subiect al pozei, de exemplu, fotograful creează o lucrare nouă, cu drepturi de autor, dar drepturile creatorului personajului afectează şi fotografia rezultată. O astfel de fotografie nu poate fi publicată fără consimţământul ambilor deţinători de drepturi de autor: fotograful şi desenatorul.

Nu contează nici măcar dacă un desen al unui personaj sub incidenţa drepturilor de autor este creat de la zero fără vreo altă referinţă decât memoria uploaderului. O lucrare aflată sub incidenţa drepturilor de autor nu poate deveni liberă fără consimţământul deţinătorul drepturilor de autor, nici prin fotografiere, nici prin desenare, nici prin sculptare.

It does not matter if a drawing of a copyrighted character's likeness is created entirely by the uploader without any other reference than the uploader's memory. A non-free copyrighted work simply cannot be rendered free without the consent of the copyright holder, not by photographing, nor drawing, nor sculpting (but see Commons:Freedom of panorama).

Locations such as theme parks usually allow photography and sometimes even encourage it even though items of copyrighted artwork will almost certainly be included in visitors' photos. Such policies, however, do not automatically mean that such photos can be distributed under a public domain dedication or a free content license; the intent of a venue allowing photography may be to facilitate photography for personal usage and/or non-commercial sharing on social networking sites, for example. (See this discussion.) Also, the legal concept of de minimis can apply in such a setting: if the subject of your theme park photograph is your daughter eating an ice cream but someone in a Mickey Mouse costume can be seen in the background, this is not considered infringement nor a derivative work so long as it is clear from the photograph that you are interested in the girl and the frozen treat rather than the oversized rodent, and you may even market that image commercially (though you must be sure that Mickey really is "de minimis" and his presence must not make that image more useful, more interesting, or more marketable than it would be without him).

Dacă pozez un copil cu o jucărie de pluş Winnie the Pooh, Disney deţine drepturile de autor ale imaginii doar pentru că deţin designul personajului Pooh?

Nu. Disney nu deţine dreptul de autor asupra fotografiei. Sunt două drepturi diferite de care trebuie ţinut cont, acelea ale fotografului (în ce priveşte fotografia) şi cele ale lui Disney (jucăria). Trebuie să faceţi distincţia. Puneţi-vă întrebarea: Poate această fotografie să ilustreze subiectul „Winnie the Pooh”? Încerc eu să ocolesc restricţiile pentru fotografii bidimensionale ale lui utilizând fotografia unei jucării? Dacă da, atunci nu este permisă.

Atenţie, însă, că strategia de protecţie a companiei Disney se bazează atât pe dreptul de autor (proprietatea artistică) cât şi pe mărcile comerciale (extinse pentru a proteja un design). Analiza legală ar fi în acest caz mai subtilă.

Nu deţine câte cineva drepturile de autor asupra oricărui produs? Cum rămâne cu maşinile? Sau scaunele de bucătărie? Carcasele de calculator?

Nu. Există prevederi speciale în legea dreptului de autor pentru a scuti o gamă largă de articole utilizare de protecţia legii:

A doua parte a amendamentului stipulează:

- „designul unui articol util [...] va fi considerat lucrare picturală, grafică, sau sculpturală doar dacă, şi doar atât cât, astfel de design include trăsături picturale, grafice, sau sculpturale ce pot fi identificate separat, şi pot exista independent de aspectele utilitare ale articolului.”

Un „articol util” este definit ca „un articol cu funcţie utilitară intrinsecă ce nu foloseşte doar pentru a reprezenta apariţia articolului sau pentru a transmite informaţie”. Această parte a amendamentului este o adaptare de limbaj adăugată la Regulamentele Copyright Office în anii 1950 ca efort de a implementa decizia Curţii Supreme americane în cazul Mazer.

Adoptând acest limbaj modificator, Commisia caută să traseze o linie cât de clar posibilă între lucrările ce intră sub incidenţa drepturilor de autor şi lucrările care nu intră sub incidenţa drepturilor de design industrial. O pictură, un desen sau o lucrare grafică bidimensională tot poate să fie identificată ca atare când este tipărită sau se aplică pe articole utilitare cum ar fi materiale textile, tapet, ambalaje şi altele asemenea. Aceasta este valabilă şi în cazul unei statui sau gravuri ce înfrumuseţează un produs industrial sau, ca în cazul Mazer, este inclus într-un produs fără pierderea abilităţii de a exista independent ca lucrare artistică. Pe de altă parte, deşi forma unui produs industrial poate fi estetică şi valoroasă, intenţia Comisiei este de a nu-i oferi acesteia protecţie conform legii. Dacă forma unui automobil, avion, rochie, televizor sau alt produs industrial nu conţine niciun element care, fizic sau conceptual, poate fi identificat ca separabil de aspectele utilitare ale articolului, designul nu intră sub incidenţa dreptului de autor. Testul de separabilitate şi independenţă de „aspectele utilitare ale articolului” nu depind de natura designului—adică, chiar dacă felul cum arată un articol este determinat de consideraţii estetice (spre deosebire de cele funcţionale), doar elementele care pot fi identificate separat de articolul util ca atare pot intra sub incidenţa dreptului de autor. Şi, chiar dacă designul tridimensional conţine un astfel de element, protecţia dreptului de autor se extinde doar asupra acelui element, şi nu acoperă întreaga configuraţie a articolului utilitar.

The test of separability and independence from "the utilitarian aspects of the article" does not depend upon the nature of the design—that is, even if the appearance of an article is determined by aesthetic (as opposed to functional) considerations, only elements, if any, which can be identified separately from the useful article as such are copyrightable. And, even if the three-dimensional design contains some such element (for example, a carving on the back of a chair or a floral relief design on silver flatware), copyright protection would extend only to that element, and would not cover the overall configuration of the utilitarian article as such.

- De la Facultatea de Drept a Universităţii Cornell note asupra Codului SUA 17 § 102

- Note that while the commentary above was apparently written while some language was an amendment which had not then been enacted, it was subsequently enacted and can be found in 17 USC 101.

Sculptures, paintings, action figures, and (in many cases) toys and models do not have utilitarian aspects and therefore in the United States (where Commons is hosted) such objects are generally considered protected as copyrighted works of art. A toy airplane, for example, is mainly intended to portray the appearance of an airplane in a manner similar to that of a painting of an airplane.[2] On the other hand, ordinary alarm clocks, dinner plates, gaming consoles— as well as actual, full-scale planes— are not generally copyrightable... though any design painted on the dinner plate would likely be subject to copyright protection, as would an alarm clock in the shape of Snoopy the dog.

Obiectele utilitare pot intra totuşi sub incidenţa drepturilor de autor (de exemplu, un ceas deşteptător de forma unui personaj din desene animate), dar nu există o demarcaţie clară universală, şi diferite jurisdicţii utilizează criterii diferite.[3][4]

De exemplu, legea germană are un termen denumit Schöpfungshöhe, adică pragul de originalitate necesar pentru protecţie legală.[5][6] Ca şi în majoritatea jurisdicţiilor, gradul de originalitate necesar pentru protecţia unor lucrări de artă aplicată sunt mai ridicate. Nu există nicio definiţie legală a acestui prag, deci se foloseşte bunul simţ şi precedentele legale.[7]

În loc de protecţia drepturilor de autor, obiectele utilitare sunt în general protejate de patente, care, în funcţie de jurisdicţie, pot limita utilizarea comercială a reproducerilor. Totuşi, patentele şi dreptul de autor sunt zone separate ale legislaţiei, şi lucrările încărcate la Commons trebuie să fie libere doar în raport cu dreptul de autor. Patentele sunt publice, deci publicarea unei reproduceri a unui obiect patentat la Commons nu poate constiti singură încălcare de patent. De aceea, patentele de acest fel nu reprezintă o problemă la Commons.

Photos of people in costumes of copyrighted characters may or may not be copyrighted.[8] See Commons:Copyright rules by subject matter#Costumes and cosplay for more information. These should be decided on a case-by-case basis using the separability test.[2]

Text

It is prohibited to copy text from non-free media like copyrighted books, articles or similar works. Information itself, however, is not copyrightable, and you are free to rewrite it in your own words. Quotations are allowed if they are limited in size and mention the source.

Ştiu că nu pot încărca fotografii ale unor lucrări de artă sub incidenţa drepturilor de autor (picturi şi statui), dar cum rămâne cu jucăriile? Jucăriile nu sunt lucrări artistice!

Vezi și: Category:Toys related deletion requests

Legal, majoritatea jucăriilor sunt lucrări artistice.[9] Dacă faceţi o fotografie a unei sculpturi, sau unei jucării Darth Vader este acelaşi lucru. Ambele intră sub protecţia dreptului de autor, în ambele cazuri copyrightul fotografiei nu înlocuieşte copyrightul original şi în ambele cazuri aveţi nevoie de permisiunea creatorului original. Nu puteţi încărca fotografii ale unei sculpturi de Picasso, nu puteţi încărca fotografii cu Mickey Mouse sau cu figurinele Pokémon.

Numeroase procese au arătat că Mickey Mouse sau Asterix trebuie trataţi ca lucrări artistice, adică ele se supun dreptului de autor, pe când o lingură sau o masă nu sunt artistice. Ele pot intra sub protecţia dreptului de autor dacă li se dă o formă foarte specială de către un designer şi sunt prezentate ca lucrări artistice (şi nu ca simple obiecte), dar cele folosite de dumneavoastră acasă cel mai probabil nu sunt aşa.

The question, then, is whether toys are to be treated as vehicles and furniture: exempt from copyright protection on the basis of being utilitarian objects. Indeed, some countries, such as Japan,[10] generally consider toys to be utilitarian objects and therefore ineligible for copyright. Other countries, such as the United States, however, do not consider toys to be utilitarian objects. Accordingly, paintings, statues and toys are all works subject to copyright whose photographs would require permission of the original creator to be hosted on the Commons. Just as you cannot upload pictures of a sculpture by Picasso, you cannot upload photographs of post-1928 Mickey Mouse or Pokémon figures.

The legal rationale in the United States has been established in numerous cases. "Gay Toys, Inc. versus Buddy L Corporation", for example, found "a toy airplane is to be played with and enjoyed, but a painting of an airplane, which is copyrightable, is to be looked at and enjoyed. Other than the portrayal of a real airplane, a toy airplane, like a painting, has no intrinsic utilitarian function."[11] Additional rulings have found, for example, "it is no longer subject to dispute that statues or models of animals or dolls are entitled to copyright protection"[12] and "There is no question but that stuffed toy animals are entitled to copyright protection."[13]

Similarly, dolls' clothing has been found to be copyrightable in the US on the grounds that it does not have a utilitarian function of providing protection from the elements or preserving modesty in the manner that clothing for humans does (the latter is a "useful article.")[2] Numerous lawsuits have shown that Mickey Mouse or Asterix have to be treated as works of art, which means they are subject to copyright, while a common spoon or a table are not works of art. Artistic elements of these items could be copyrighted, but only if it's separable from the utilitarian elements.[14] Some toys are also too simple to meet the threshold of originality, for example, the Kong dog toy.[15] "A toy model that is an exact replica of an automobile, airplane, train, or other useful article where no creative expression has been added to the existing design" is not eligible for copyright protection in the United States.[16]

In other cases, the "separability" test may be needed (see Star Athletica, LLC v. Varsity Brands, Inc.). Consensus on Commons has found that sex dolls are copyrightable, as their design elements are separable from their utilitarian function.

When uploading a picture of a toy, you must show that the toy is in the public domain in both the United States and in the source country of the toy. In the United States, copyright is granted for toys even if the toy is ineligible for copyright in the source country.[17]

Dar Wikimedia Commons nu este un site comercial! Cum rămâne cu utilizarea cinstită?

Wikimedia Commons nu este un proiect comercial, dar sfera de interes impune ca orice imagine să poată fi utilizată comercial sub licenţe libere. Fiecare imagine sau fişier media trebuie să fie liber de orice copyright al vreunui terţ.

Utilizarea cinstită nu este permisă la Commons. „Utilizarea cinstită” este o excepţie legală dificilă pentru imagini utilizate într-un anume context limitat; nu se aplică la întregi baze de date de material sub incidenţa drepturilor de autor.

Dar cum putem ilustra subiecte ca Războiul Stelelor sau Pokémon fără poze?

Este adevărat, poate fi dificil sau chiar imposibil de ilustrat astfel de articole. Articolele pot fi însă scrise. Lipsa de ilustraţii nu afectează funcţionarea proiectelor Wikimedia, şi sunt numeroase domenii în care se pot realiza ilustraţii ce nu încalcă drepturile de autor.

Unele proiecte Wikimedia permit încărcarea de lucrări non-libere (inclusiv lucrări derivate ale unor lucrări non-libere) în conformitate cu utilizarea cinstită. Situaţiile în care aceasta este permisă sunt limitate strict. Este vital să consultaţi politicile şi îndrumarele proiectului în chestiune înainte de a recurge la utilizarea cinstită.

What about images of copyrighted characters in public domain works?

Sometimes individual works featuring copyrighted characters (such as Winnie the Pooh or Mickey Mouse or Sherlock Holmes) enter the public domain. Only aspects of the character that appear in the public domain work may be used to create a new derivative work. Aspects of the character that appear in works under an active copyright are still protected. For instance in Warner Bros. v. AVELA a promotional poster for the movie The Wizard of Oz was never copyrighted. A t-shirt company combined the public domain images from the poster with catchphrases from the 1939 film that was still under an active copyright. The court ruled that only the images were public domain and that combining them with the copyrighted catchphrases created a new work that infringed Warner Bros. active copyright for the film.

[18] See also: Commons:Deletion requests/File:"Appreciate America. Come On Gang. All Out for Uncle Sam" (Mickey Mouse)" - NARA - 513869.tif for additional court rulings.

Derivative representations of characters are protected by copyright law in the United States until the original work that created the character is no longer copyrighted.[18] This protection is separate from trademark protection. See Commons:Character copyrights for information on the copyright status of specific characters.

N-am mai auzit de aşa ceva până acum! Asta nu e cumva o interpretare originală?

Să ştiţi că nu. Fotografiile, să zicem, ale statuilor sau picturilor moderne nu pot fi încărcate nici ele, şi acest lucru este acceptat. Dacă noi acceptăm standardul legal conform căruia figurinele de benzi desenate şi jucăriile pot fi considerate lucrări artistice protejate de drepturile de autor, noi doar aplicăm legile în vigoare.

Cazuri particulare

Vezi și: Commons:Copyright rules by subject matter.

Cum afectează această politică selecţia imaginilor permise la Wikimedia Commons?

- Personajele de desene animate, benzi desenate şi jucăriile realizate pe baza lor: Nu se permit fotografii, desene, picturi sau alte copii/lucrări derivate ale acestora (atâta vreme cât originalul nu este în domeniul public). Nu se permit imagini ale elementelor derivate din figurile protejate, cum ar fi păpuşi, jucării, tricouri, sacoşe tipărite, scrumiere etc.

- Picturi înrămate: Picturile aflate în domeniul public sunt în general permise (vezi Commons:Licenţiere). Ramele sunt obiecte tridimensionale, deci fotografia poate fi sub incidenţa drepturilor de autor. Ţineţi minte: Pe cât posibil, furnizaţi numele şi datele naşterii şi decesului creatorului şi momentul creării! Dacă nu le ştiţi, daţi cât mai multe informaţii despre sursă (legătură către site, locul publicării etc.). Alţi voluntari trebuie să poată verifica statutul drepturilor de autor. Mai mult, dreptul moral al creatorului original—care include dreptul de a fi recunoscut ca autor—este nelimitat în unele ţări. În orice caz, aveţi nevoie de permisiunea autorului pentru a crea o lucrare derivată. Fără această permisiune, orice obiect artistic creat de dumneavoastră pe baza lucrării lor este considerată, din punct de vedere legal, copie nelicenţiată proprietate a autorului original (preluarea de pe un alt site web nu este permisă fără permisiunea lor).

- Cave paintings: Cave walls are usually not flat, but three-dimensional. The same goes for antique vases and other uneven or rough surfaces. This could mean that photographs of such media can be copyrighted, even if the cave painting is in the public domain. (We are looking for case studies here!) Old frescoes and other paintings on flat surfaces in the public domain should be fine, as long as they are reproduced as two-dimensional artworks.

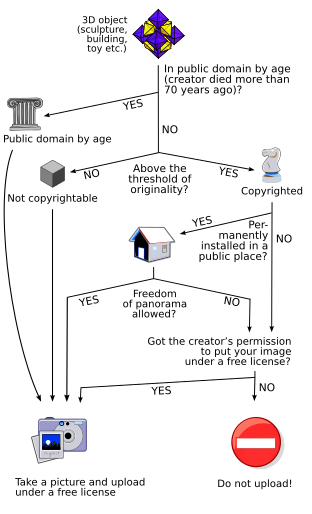

- Fotografii ale clădirilor şi lucrărilor artistice amplasate permanent în locuri publice: Acestea sunt şi ele lucrări derivate, dar pot fi OK, dacă lucrarea este instalată permanent (adică, acolo rămâne, nu este înlăturată după o vreme) în unele ţări dacă vă aflaţi într-un loc public când faceţi fotografia. Verificaţi Commons:Freedom of panorama pentru a vedea dacă ţara în care vă aflaţi are o politică liberală în ce priveşte această excepţie şi pentru a afla mai multe despre libertatea de panoramă. (În majoritatea ţărilor, libertatea de panoramă nu acoperă lucrările bidimensionale, cum ar fi picturile murale.)

- Replici ale lucrărilor de artă: Replicile exacte ale lucrărilor în domeniul public, cum ar fi suvenirurile cu Venus din Milo, nu pot atrage un nou drept de autor, întrucât nu conţin nimic original. Astfel, fotografiile unor astfel de obiecte pot fi tratate ca şi fotografii ale lucrării de artă.

- Fotografiile obiectelor tridimensionale sunt întotdeauna sub incidenţa dreptului de autor, chiar dacă obiectul însuşi este în domeniul public. Dacă nu aţi făcut dumneavoastră fotografia, aveţi nevoie de permisiunea deţinătorului dreptului de autor al fotografiei (desigur, dacă fotografia nu este ea însăşi în domeniul public).

- Imagini ale personajelor/obiectelor/scenelor din cărţi se supun aceluiaşi drept de autor ca şi cartea însăşi. Nu puteţi crea şi distribui liber un desen cu Albus Dumbledore cum nu puteţi distribui nici un film Harry Potter făcut de dumneavoastră. În orice caz, vă trebuie permisiunea autoruluide a crea o lucrare derivată. Fără această permisiune, orice lucrare artistică creată de dumneavoastră pe baza lucrării lor este considerată copie nelicenţiată proprietate intelectuală a autorului original.

- Fan art : Vedeţi Commons:Fan art

Tagging non-free derivative works

If you come across derivative works of non-free works on Commons, tag them with {{SD|F3}} for speedy deletion.

Derivatives of Free works

In general, derivatives of free works (such as described in Commons:Collages, but also any related work that modifies it) are usually allowed. However, there must be compatible licensing used. For Creative Commons licenses, see Compatible Licenses:

- Adapting works licensed under CC BY-SA version 2 or higher can be re-licensed under the same or higher version of CC BY-SA (e.g. a derivative of a CC BY-SA 3 work could be either 3, 4, or both).

- Adapting works licensed under CC BY-SA version 1 must be re-licensed as CC BY-SA 1.

- Adapting works licensed under CC BY licenses can either use the original version or later versions of CC BY, or included in CC BY-SA (see "Can I include a work licensed with CC BY in a Wikipedia article even though they use a CC BY-SA license?")

- If you're making a derivative of something else you yourself made, you can simplify this by Multi-licensing your earlier upload under more licenses. (So if you had a version 1 CC license, you can just go back and add a version 4 license, which simplifies things greatly.)

- Adapting public domain or CC0 material means you have full freedom in picking a license for a derivative work.

Vezi şi

- Collages are combinations of multiple images arranged into a single image

- Screenshots are a type of derivative work

Referințe

- ↑ U.S. Copyright Act of 1976, Section 101. Retrieved on 2019-04-17.

- ↑ a b Pearlman, Rachel (2012-09-17). IP Frontiers: From planes to dolls: Copyright challenges in the toy industry. NY Daily Record. Retrieved on 2014-06-21.

- ↑ Weinberg, Michael (January 2013). What's the Deal with Copyright and 3D Printing? 9. Public Knowledge. Retrieved on 2016-09-22.

- ↑ Weinberg, Michael (January 2013). What's the Deal with Copyright and 3D Printing? 13. Public Knowledge. Retrieved on 2016-09-22.

- ↑ Summary Report: The Interplay Between Design and Copyright Protection for Industrial Products 4–5. AIPPI.

- ↑ VSL0069492. Retrieved on 29 October 2013.

- ↑ Compendium II: Copyright Office Practices - Chapter 500. University of New Hampshire School of Law.

- ↑ Commons:Deletion requests/Images of costumes tagged as copyvios by AnimeFan#Comment by Mike Godwin

- ↑ 17 U.S. Code § 102. Subject matter of copyright: In general. Retrieved on 2019-04-17.

- ↑ "Farby" doll is judged not to be a work of art. Sendai High Court (9 July 2002). Retrieved on 2019-04-17.

- ↑ (Gay Toys, Inc. v. Buddy L Corporation, 703 F.2d 970 (6th Cir. 1983)

- ↑ Blazon, Inc. v. DeLuxe Game Corp., 268 F. Supp. 416 (S.D.N.Y. 1965)

- ↑ R. Dakin & Co. v. A & L Novelty Co., Inc., 444 F. Supp. 1080, 1083-84 (E.D.N.Y. 1978)

- ↑ [1] Public domain maps]. Public Domain Sherpa. Retrieved on 2019-04-17.

- ↑ Kong Design (20 September 213). Retrieved on 2019-04-17.

- ↑ Compendium III § 313.4(A)

- ↑ HASBRO BRADLEY, INC. v. SPARKLE TOYS, INC., 780 F.2d 189 (2nd Cir. 1985).

- ↑ a b Warner Bros. v. AVELA (2011).

Legături externe

- Studii de caz

- http://www.ivanhoffman.com/beanie.html (Un caz legal în care fotografiile păpuşilor Beanie Baby sunt tratate ca lucrări derivate)

- http://www.benedict.com/visual/batman/batman (Un caz legal în care Warner Bros a fost acuzată de încălcarea drepturilor de autor pentru filmarea unei statui dintr-o clădire)

- http://www.stmaryslawjournal.org/pdfs/gorman.pdf (Eric D. Gorman: How to determine whether appropriation art is transformative “fair use” or morely an unauthorized derivative?)

- Alte site-uri utile

- Derivative Works :: Topics :: Lumen (formerly Chilling Effects)

- L.H.O.O.Q.--Internet-Related Derivative Works

- US Copyright Office Circular 14 - Copyright in Derivative Works and Compilations

- Compendium II: Copyright Office Practices - Chapter 500 (Ce intră sub incidenţa drepturilor de autor şi ce nu?)

- Australian Copyright Council's Online Information Centre cu multe îndrumare privind diverse aspecte ale drepturilor de autor.