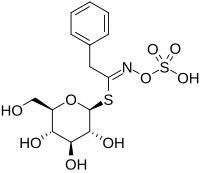

Glucotropaeolin

| Strukturformel | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||

| Allgemeines | |||||||||||||

| Name | Glucotropaeolin | ||||||||||||

| Andere Namen |

1-S-[(1Z)-2-Phenyl-N-(sulfooxy)ethanimidoyl]-1-thio-β-D-glucopyranose | ||||||||||||

| Summenformel | C14H19NO9S2 | ||||||||||||

| Externe Identifikatoren/Datenbanken | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Eigenschaften | |||||||||||||

| Molare Masse | 409,4 g·mol−1 | ||||||||||||

| Sicherheitshinweise | |||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||

| Soweit möglich und gebräuchlich, werden SI-Einheiten verwendet. Wenn nicht anders vermerkt, gelten die angegebenen Daten bei Standardbedingungen (0 °C, 1000 hPa). | |||||||||||||

Glucotropaeolin (auch Benzylglucosinolat) ist eine chemische Verbindung aus der Gruppe der Glucosinolate.

Vorkommen

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Zuerst nachgewiesen wurde Glucotropaeolin 1899 in der Großen Kapuzinerkresse.[2] Es kommt auch in Papaya-Kernen vor.[3][4] In Garten-Kresse kommt es zusammen mit Gluconasturtiin vor.[5] In Acker-Rettich kommt es neben Glucoraphanin und Glucoerucin vor.[6]

Biosynthese

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Die Biosynthese des Glucotropaeolins geht von Phenylalanin aus und verläuft über Phenylacetaldoxim als Intermediat.[7]

Herstellung

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Glucotropaeolin kann hergestellt werden, indem N-hydroxyphenylacetimidoylchlorid (aus Phenylacetaldoxim und Chlorgas in Chloroform) mit Tetraacetylglucopyranosylthiol in Gegenwart von Triethylamin umgesetzt wird. Durch Umsetzung mit Schwefeltrioxid-Pyridinkomplex kann diese Verbindung sulfatiert werden und anschließend durch Umsetzung mit Ammoniak in Methanol deacetyliert werden, wodurch Glucotropaeolin erhalten wird.[8] Die biotechnologische Herstellung mittels einem modifizierten Stamm von E. Coli ist ebenfalls möglich.[9]

Eigenschaften

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]Bei der Hydrolyse von Glucotropaeolin durch die Myrosinase entsteht Benzylisothiocyanat.[10]

Einzelnachweise

[Bearbeiten | Quelltext bearbeiten]- ↑ Dieser Stoff wurde in Bezug auf seine Gefährlichkeit entweder noch nicht eingestuft oder eine verlässliche und zitierfähige Quelle hierzu wurde noch nicht gefunden.

- ↑ Ivica Blažević, Sabine Montaut, Franko Burčul, Carl Erik Olsen, Meike Burow, Patrick Rollin, Niels Agerbirk: Glucosinolate structural diversity, identification, chemical synthesis and metabolism in plants. In: Phytochemistry. Band 169, Januar 2020, S. 112100, doi:10.1016/j.phytochem.2019.112100.

- ↑ Rohan Kermanshai, Brian E McCarry, Jack Rosenfeld, Peter S Summers, Elizabeth A Weretilnyk, George J Sorger: Benzyl isothiocyanate is the chief or sole anthelmintic in papaya seed extracts. In: Phytochemistry. Band 57, Nr. 3, Juni 2001, S. 427–435, doi:10.1016/S0031-9422(01)00077-2.

- ↑ Ze-You Li, Yong Wang, Wen-Tao Shen, Peng Zhou: Content determination of benzyl glucosinolate and anti–cancer activity of its hydrolysis product in Carica papaya L. In: Asian Pacific Journal of Tropical Medicine. Band 5, Nr. 3, März 2012, S. 231–233, doi:10.1016/S1995-7645(12)60030-3.

- ↑ Fekadu Kassie, Brenda Laky, Richard Gminski, Volker Mersch-Sundermann, Gerlinde Scharf, Evelyn Lhoste, Siegfried Kansmüller: Effects of garden and water cress juices and their constituents, benzyl and phenethyl isothiocyanates, towards benzo(a)pyrene-induced DNA damage: a model study with the single cell gel electrophoresis/Hep G2 assay. In: Chemico-Biological Interactions. Band 142, Nr. 3, Januar 2003, S. 285–296, doi:10.1016/S0009-2797(02)00123-0.

- ↑ Mayank S. Malik, Melissa B. Riley, Jason K. Norsworthy, William Bridges: Glucosinolate Profile Variation of Growth Stages of Wild Radish (Raphanus raphanistrum). In: Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. Band 58, Nr. 6, 24. März 2010, S. 3309–3315, doi:10.1021/jf100258c.

- ↑ E. W. Underhill: Biosynthesis of Mustard Oil Glucosides:: Conversion of P)henylacetaldehyde Oxime and 3‐Phenylpropionaldehyde Oxime to Glucotropaeolin and Gluconasturtiin. In: European Journal of Biochemistry. Band 2, Nr. 1, Juli 1967, S. 61–63, doi:10.1111/j.1432-1033.1967.tb00106.x.

- ↑ M. H. Benn: A NEW MUSTARD OIL GLUCOSIDE SYNTHESIS: THE SYNTHESIS OF GLUCOTROPAEOLIN. In: Canadian Journal of Chemistry. Band 41, Nr. 11, 1. November 1963, S. 2836–2838, doi:10.1139/v63-415.

- ↑ Annette Petersen, Christoph Crocoll, Barbara Ann Halkier: De novo production of benzyl glucosinolate in Escherichia coli. In: Metabolic Engineering. Band 54, Juli 2019, S. 24–34, doi:10.1016/j.ymben.2019.02.004.

- ↑ John Jensen, Bjarne Styrishave, Anne Louise Gimsing, Hans Christian Bruun Hansen: The toxic effects of benzyl glucosinolate and its hydrolysis product, the biofumigant benzyl isothiocyanate, to Folsomia fimetaria. In: Environmental Toxicology and Chemistry. Band 29, Nr. 2, Februar 2010, S. 359–364, doi:10.1002/etc.33.