Abstract

Organisation-based recommender interfaces (ORGs) have drawn attention from both the academia and the industry as they allow users to determine their preferences for product attributes. Considering that users’ personality traits may deeply influence their shopping behaviour, we performed an eye-tracking lab experiment to compare two types of recommender interfaces, namely the classified evaluation ORG and the non-classified evaluation list. The results showed that highly conscientious users paid significantly more attention to ORG, evaluated slightly more products, and placed more fixations on each product in the ORG. Whereas, low conscientiousness users exhibited more fixations on the LIST interface. Hence, the empirical findings suggest that users with different personalities adapted their visual searching behaviour to the change in the recommendation presentation.

You have full access to this open access chapter, Download conference paper PDF

Similar content being viewed by others

Keywords

1 Introduction

Organisation-based recommender interfaces (ORGs) have become increasingly popular in various web environments [7, 10, 11]. Previous studies have indicated that ORG can increase the users’ product knowledge and preference [8, 9]. Hence, users could be assisted in gaining a quicker overview and understanding of the recommended items. According to the related work, the level of users’ conscientiousness may influence their subjective perception of the recommender interfaces. People with high conscientiousness are often highly disciplined, organised, cautious, dutiful, and consistent in their behaviour and styles, whereas those low in this trait tend to be more impulsive, creative, easy-going, and flexible [25]. For instance, conscientiousness has been demonstrated to be related to the preference for different levels of recommendation diversity in the music and movie domains [4]. The findings show the necessity of considering individual traits while designing diversity-aware interfaces. In [1], researchers proposed a strategy that embeds personality to adjust the diversity degree of recommendations; the results showed that it significantly increased the users’ perceptions of system competence and the recommendation accuracy. A study of 1840 users of MovieLens showed that conscientiousness was associated with the preference for the diversity degree and that highly conscientious participants were more satisfied with diverse lists [21]. However, most of the studies conducted thus far have focused on recommendation algorithms, without considering the users’ personality traits. Therefore, it is meaningful to explore the relationship between these personality traits and an organisation-based recommender.

In our work, we built two distinct interfaces, namely an ORG interface (classified evaluation ORG) and a list interface (non-classified evaluation list). Then, we used the Five Factor Model (FFM) to classify the score of uses with high and low levels of conscientiousness. In an eye-tracking experiment, we compared the noteworthy differences between the interfaces of the uses with these two levels of conscientiousness and conducted a data analysis at the category level and the product level. We recorded and analysed the eye-movement behaviour of conscientious users, summarised the experimental findings, and provided valuable proposals for future work.

2 Related Work

2.1 Recommender Interfaces

With respect to the general e-commerce site design in usability studies, it has been suggested that users are likely to adapt their decision strategies to information representations. For instance, in [16], the researchers reported that a product list interface can induce a significant effect on the users’ decision strategy. From the structural viewpoint, previous studies such as the one reported in [17] claimed that a site’s navigational structure directly affects shopping behaviour. In [19], the researchers discussed the effectiveness of one-column and multi-column layouts for rendering large textual documents in a web browser. They indicated that users spent less time scrolling and performed fewer scrolling actions in the case of a multi-column layout. In addition, in [18], the researchers claimed that a well-organised interface, well-designed product lists, and sufficient product information, such as product descriptions and images, can improve the accessibility of product information to online shoppers. Most of the existing systems, e.g., case-based systems, CF-based systems, and commercial sites, typically use the ranked list structure, where all items are displayed one after the other. The ranking is primarily based on scores that the system computes to predict a user’s interest in the items [20]. For instance, MovieLens is a typical CF-based movie recommender system. By locating neighbours who have similar interests to the current user, the system recommends a set of movies that are preferred by these like-minded people [23]. Indeed, according to [24], in the list structure, researchers have found that people more frequently viewed and clicked the top results on the list.

To the best of our knowledge, and according to [6], keyword-style explanations are significantly more effective than recommended-item lists. For example, one study showed that the ORG interface performed substantially better at improving the quality of user-perceived recommendations [7, 10]. There has been some research on increasing the users’ decision effectiveness. For instance, by using a case-based reasoning system in [15], the researchers highlighted the need to help users to effectively explore the product space by explaining the existence of the remaining products. Meanwhile, for interface design, in [11], the researchers explored all the design issues to derive effective principles, such as how to generate categories and whether to use short or long text for the category explanation. In [22], the researchers reported two experiments on recommender interfaces; the results showed that the ORG can significantly attract the users’ attention and allow users to view more recommended items. However, as mentioned earlier, few studies have been conducted on the effect of layout design on users’ behaviour in a recommender system. Given that the list interface is so far the most popular presentation style, it should be meaningful to compare the ORG interface with it, so as to identify the interface’s genuine benefits to users. We were hence motivated to conduct user evaluations to investigate the effect of the category structure particularly in recommender systems.

2.2 Conscientiousness of FFM with Recommender Interface

The most commonly used model personality is the FFM [13], and it is traditionally captured by questionnaires such as the Big Five Inventory [5, 12]. Personal characteristics influence the form of recommendation interface [11]. As our work focuses on the effects of personality traits on the users’ eye-movement behaviour with recommendation interfaces, we mainly introduce the related work on the relationship between conscientiousness and recommendation interfaces, and the empirical results. Prior work found that conscientiousness is negatively correlated with rating items and an ability to undertake difficult activities [2]. In [3], the researchers considered personality traits to be an indicator of satisfaction and attractiveness on differently diversified music recommendation lists. The results showed that conscientiousness is related to a preference for a higher degree of diversification and is increasingly more attracted to more diversified recommendation lists. In a recommendation system [1], the researchers reported that conscientiousness can affect user behaviour in a variety of ways, such as newcomer retention, intensity of engagement, activity types, and item categories. In [21], the researchers claimed that conscientiousness is associated with a greater degree of diversity in preference, and highly conscientious participants are more satisfied and attracted to diverse lists. In another work [4], the users’ personality traits influenced the design of a diversity-aware recommendation interface. The results showed that higher conscientiousness led to a higher preference for more meta information. Moreover, they indicated that users scoring high on conscientiousness showed a preference for browsing by activity. In [14], the researchers simulated an online music streaming service to identify the relationship between personality traits and the way users browse for music (Table 1).

3 Eye-Tracking Experiment

3.1 Materials

An experiment was conducted to measure users’ performances in ORG and list interfaces, which chose smartphone as the product domain. For the ORG interface, the top candidate was displayed on the top of the interface. 24 recommended products were divided into four groups, with a title at the top of every group explaining the pros and cons of the products. For the list interface, we only displayed one line of 24 products. The experiment allowed us to further identify and judge the effects of users’ conscientiousness level on their eye-movement behaviours in two different interfaces.

3.2 Materials Experimental Procedure and Participants

The user’s task was to identify a product that he/she would buy if he/she had an opportunity to do so. An administrator was present to help the participants complete the experiment. The experiment consisted of four parts:

-

The subjects were initially tested on the Big Five Inventory. The participants were asked to answer 44 questions.

-

According to their daily habits, the users assumed a shopping scenario and selected their preferred products.

-

The participants entered their choices to select a product in the ORG and the list interface.

-

In the experiment, we used the Tobii Pro TX300 eye tracker to record the fixation duration.

We launched an online user study through various channels. Finally, we recruited 136 participants to join the study. Each participant was rewarded with an incentive. Most of the participants had bachelor’s degrees or above and had some shopping experience. Meanwhile, the participants were averaged over each group. Through a median split, we classified the users into two types in each dimension, that is, high or low level of conscientiousness. Finally, we filtered out the data where the fixation time was less than 30 s and screened out 108 valid data items (Table 2).

3.3 AOI Definitions and Metrics

In our work, the AOI was determined at two levels: category level and product level. At the category level, there were five areas in each interface. In the ORG interface, each recommendation module as a group was an AOI area. In the list interface, the top of the interface was an AOI area, and six products as a group were an AOI area. At the product level, each recommended product was defined as an AOI, and each recommended title was regarded as another AOI. According to the experiments, we selected the following metrics:

-

Time to first fixation: time from the start of the stimulus display until the test participants fixate on the AOI for the first time

-

Fixation duration: duration of each individual fixation within an AOI

3.4 Hypotheses

Combined with the relevant literature, in total, we had three hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 1: Highly conscientious users spend more time browsing the ORG interface than the list. Users with a low level of conscientiousness are the opposite.

-

Hypothesis 2: A high level of conscientiousness correlates with the ORG interface, and conscientious users prefer to browse ORG.

-

Hypothesis 3: Highly conscientious users are more significant in terms of the numbers of products and the degree of attention.

4 Eye-Tracking Experiment

According to the valid data, we quantified the effects of individual traits on the user experience with the recommender interfaces. In the following paragraphs, we present the results in two forms, namely the heat map, and the AOI analysis result.

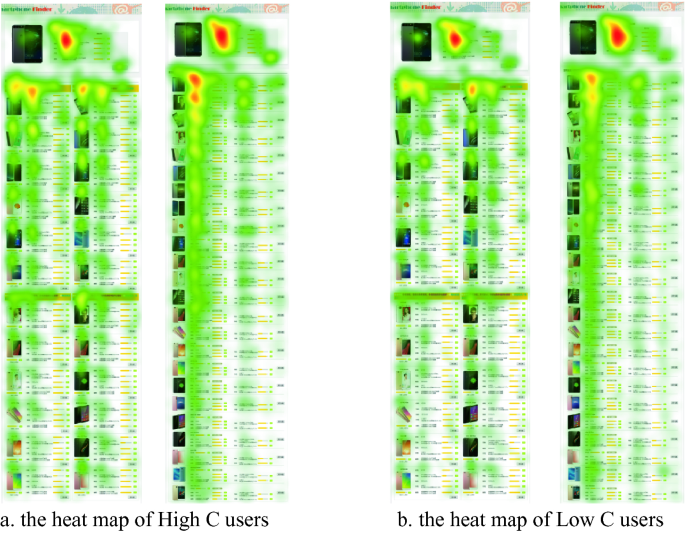

4.1 Result 1: Heat Map

We will first present the heat map because it is a powerful way of visualising the users’ fixation distribution. We summed all of the participants’ fixations on an interface to produce the heat map (see Fig. 1). The red/orange colour indicates that almost all of the users halted their gaze at a specific part of the interface, and the green colour shows that few users halted in the area. High C stands for a high level of conscientiousness, and Low C stands for a low level of conscientiousness.

The heat map shows that High C users paid greater attention to category titles and read more product details in the ORG interface. This indicated that users with a high level of conscientiousness preferred to browse product information and compare products comprehensively and preferred a more comprehensive and organised product recommendation interface.

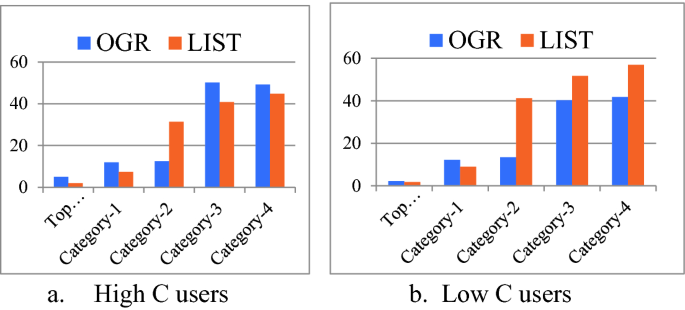

4.2 Result 3: AOI Analyses

In the following text, we present an in-depth AOI analysis for identifying whether the differences between ORG and LIST were significant.

Category Level.

According to the time to first fixation in AOI, both the High C and the Low C users scanned products by basically following the same path on the two interfaces: Top Candidate → Category-1 → Category-2 → Category-3 → Category-4. The difference between the two user groups was that the High C users took longer to fixate on Category-3 and Category-4 in ORG. In contrast, the Low C users took longer to notice the two bottom categories in LIST (see Fig. 2)

With respect to the fixation duration, users with high C paid significantly more attention to ORG (54.09 s vs. 43.79 s in LIST, p = .035). Concretely, the comparison of fixations at each category level of AOI between the two interfaces showed that all the five category-level AOIs received more fixations in ORG. In particular, the differences for Category-2 and Category-4 were significant (Category-2: 13.37 s vs. 10.08 s in LIST, p < .01; Category-4: 7.69 s vs. 3.86 s in LIST, p < .01, see Table 3).

In contrast, for users with low C, significantly more fixations were placed on LIST (53.84 s vs. 39.20 s in ORG, p = .028). To be specific, all the five category-level AOIs received more fixations in LIST, with a significant difference for Category-1 (18.51 s vs. 10.88 s in ORG, p < .01, see Table 3).

Therefore, the interaction effect between the interface and the conscientiousness level was significant with respect to Top Candidate (F (1,106) = 12.181, p = .001), Category-1 (F (1,106) = 8.195, p = .005), and Category-4 (F (1,106) = 10.488, p = .002, see Table 3).

Product Level.

We further conducted a product-level AOI analysis for both units of individual product and category explanation (in ORG). The results showed that users with High C evaluated slightly more products in ORG (19.46 vs. 19.26 in LIST) and placed more fixations on each product (2.34 s vs. 2.12 s in LIST). Among the Low C users, both the number of evaluated products and the fixation duration for each product in the case of ORG were significantly lower than those in LIST (6.63 vs. 18.71, p = .076; 1.98 s vs. 2.60 s, p = .031, see Table 4).

With respect to the fixations on the category explanations in ORG, both the High C and the Low C users did not show a significant difference (the number of viewed explanations: 2.84 vs. 2.61; fixation duration per explanation: 1.44 s vs. 1.12 s, see Table 5).

5 Conclusions

Traditional product recommender interfaces normally present multiple recommended items in a ranked list, which we call the LIST interface. Recently, ORG has been developed to well combine the ideas of presenting diversity, and trade-off reasoning. According to the related work, there is a relationship between personality traits and shopping behaviour. Hence, in the work reported in this article, we studied the eye movements of users with different personalities through an eye-tracking experiment. We reported the results from a high or low level of conscientious user study performed by comparing an ORG interface to LIST. Specifically, we observed the user’s objective behaviour, including the fixation count, fixation duration, and the user’s final decision. The study revealed that users with different personalities adapted their visual searching behaviour to the change in the recommendation presentation. The results interestingly showed that highly conscientious users were significantly attracted by the ORG interface, while low conscientiousness users exhibited more fixations on the LIST interface. Therefore, for the highly conscientious users, we suggested that the ORG would more likely encourage a rigorous choice-making process and enable more users to reach an informed decision at the end. In the future, we intend to analyse other personality traits so as to further enhance our ORG.

References

Wu, W., Chen, L., He, L.: Proceedings of the 24th ACM Conference on Hypertext and Social Media - HT. Using Personality to Adjust Diversity in Recommender Systems, pp. 225–229 (2013)

Hu, R., Pu, P.: Exploring relations between personality and user rating behaviors. In: UMAP Workshops, Rome, Italy (2013)

Ferwerda, B., Graus, M., Vall, A., Tkalčič, M., Schedl, M.: The influence of users’ personality traits on satisfaction and attractiveness of diversified recommendation lists. In: Proceedings of the 4th Workshop on Emotions and Personality in Personalized Systems (2016)

Jin, Y., Tintarev, N., Verbert, K.: Effects of individual traits on diversity-aware music recommender user interfaces. In: Proceedings of the 26th Conference on User Modeling, Adaptation and Personalization, pp. 291–299 (2018)

Costa Jr., P.T., McCrae, R.R.: Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI). Psychological Assessment Resources, Odessa (1992)

Herlocker, J.L., Konstan, J.A., Riedl, J.: Explaining collaborative filtering recommendations. In: ACM Conference on Computer Supported Cooperative Work, vol. 22, pp. 241–250 (2000)

Chen, L., Pu, P.: Interaction design guidelines on critiquing-based recommender systems. User Model. User-Adap. Inter. 19(3), 167 (2009)

Xie, H., Wang, D.D., Rao, Y., Wong, T.L., Raymond, L.Y.K., Chen, L., et al.: Incorporating user experience into critiquing-based recommender systems: a collaborative approach based on compound critiquing. Int. J. Mach. Learn. Cybern. 9(6), 1–16 (2016)

Chen, G., Chen, L.: Augmenting Service Recommender Systems by Incorporating Contextual Opinions from User Reviews. Kluwer Academic Publishers, Hingham (2015)

Chen, L., Chen, G., Wang, F.: Recommender systems based on user reviews: the state of the art. User Model. User-Adap. Inter. 25(2), 99–154 (2015)

Bollen, D., Knijnenburg, B.P., Willemsen, M.C., Graus, M.: Understanding choice overload in recommender systems. In: Proceedings of the fourth ACM conference on RecSys, pp. 63–70. ACM (2010)

Tkalčič, M., Chen, L.: Personality and recommender systems. In: Ricci, F., Rokach, L., Shapira, B. (eds.), Recommender Systems Handbook, pp. 715–739 (2015)

Goldberg, L.R.: An alternative description of personality: the big-five factor structure. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 59(6), 1216–1229 (1990)

Ferwerda, B., Schedl, M.: Personality-based user modeling for music recommender systems. In: Berendt, B., Bringmann, B., Fromont, É., Garriga, G., Miettinen, P., Tatti, N., Tresp, V. (eds.) ECML PKDD 2016. LNCS (LNAI), vol. 9853, pp. 254–257. Springer, Cham (2016). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-46131-1_29

Yan, H., Wang, Z., Lin, T.H., Li, Y., Jin, D.: Profiling users by online shopping behaviors. Multimedia Tools Appl. 5, 1–11 (2017)

Jedetski, J., Adelman, L., Yeo, C.: How web site decision technology affects consumers. IEEE Internet Comput. 6(2), 72–79 (2002)

Markus, M., Soh, C.: Structural influences on global e-commerce activity. J. Global Inf. Manag. 10(1), 5–12 (2002)

Callahan, E., Koenemann, J.: A comparative usability evaluation of user interfaces for online product catalog. In: Proceedings of the 2nd ACM Conference on Electronic Commerce, pp. 197–206. ACM, NY (2000)

Braganza, C., et al.: Scrolling behaviour with single- and multi-column layout. In: Proceedings of the 18th International Conference on World Wide Web (WWW), pp. 831–840. ACM, NY (2009)

Adomavicius, G., Tuzhilin, A.: Toward the next generation of recommender systems: a survey of the state-of-the-art and possible extensions. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 17(6), 734–749 (2005)

Karumur, R.P., Nguyen, T.T., Konstan, J.A.: Personality, user preferences and behavior in recommender systems. Inf. Syst. Front. 6, 1–25 (2017)

Chen, L., Pu, P.: Experiments on user experiences with recommender interfaces. Behav. Inf. Technol. 33(4), 372–394 (2014)

Konstan, J.A., et al.: GroupLens: applying collaborative filtering to usenet news. Commun. ACM 40(3), 77–87 (1997)

Dumais, S., Cutrell, E., Chen, H.: Optimizing search by showing results in context. In: Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, pp. 277–284. ACM, NY (2001)

Hogan, J., Ones, D.S.: Conscientiousness and integrity at work. In: Hogan, R., Johnson, J.A., Briggs, S.R. (eds.) Handbook of Personality Psychology, pp. 849–870 (1997)

Acknowledgement

This research work was supported by the Fundamental Research Funds of Shandong University, China. We thank all participants who took part in our experiments and teachers and friends who support us.

Author information

Authors and Affiliations

Corresponding author

Editor information

Editors and Affiliations

Rights and permissions

Copyright information

© 2019 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this paper

Cite this paper

Zhang, L., Liu, H. (2019). Effects of Conscientiousness on Users’ Eye-Movement Behaviour with Recommender Interfaces. In: Nah, F.FH., Siau, K. (eds) HCI in Business, Government and Organizations. eCommerce and Consumer Behavior. HCII 2019. Lecture Notes in Computer Science(), vol 11588. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22335-9_25

Download citation

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-22335-9_25

Published:

Publisher Name: Springer, Cham

Print ISBN: 978-3-030-22334-2

Online ISBN: 978-3-030-22335-9

eBook Packages: Computer ScienceComputer Science (R0)