Abbotsford is a historic country house in the Scottish Borders, near Galashiels, on the south bank of the River Tweed. Now open to the public, it was built as the residence of historical novelist and poet Sir Walter Scott between 1817 and 1825.[1] It is a Category A Listed Building[2] and the estate is listed in the Inventory of Gardens and Designed Landscapes in Scotland.[3]

| Abbotsford | |

|---|---|

Abbotsford in 1880 | |

| Former names | Cartleyhole, Clarty Hole |

| General information | |

| Type | Baronial Mansion |

| Architectural style | Gothic Revival |

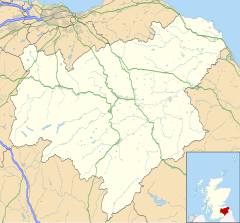

| Location | Scottish Borders |

| Address | Galashiels |

| Town or city | Near Galashiels |

| Country | Scotland |

| Coordinates | 55°35′59″N 2°46′55″W / 55.59972°N 2.78194°W |

| Renovated | 1817–1825 |

| Owner | Scott Family |

| Designations | Category A Listed Building |

Description

editThe nucleus of the estate was a farm of 100 acres (0.40 km2), called Cartleyhole, nicknamed Clarty (i.e., muddy) Hole, and was bought by Scott on the lapse of his lease (1811) of the neighbouring house of Ashestiel.[4] Scott renamed it "Abbotsford" after a neighbouring ford used by the monks of Melrose Abbey.[5]

Following a modest enlargement of the original farmhouse in 1811–1812, massive expansions took place in 1816–1819 and 1822–1824. In this mansion Scott gathered a large library, a collection of ancient furniture, arms and armour, and other relics and curiosities especially connected with Scottish history, notably the Celtic Torrs Pony-cap and Horns and the Woodwrae Stone, all now in the Museum of Scotland.[6][7] Scott described the resulting building as "a sort of romance in Architecture"[8] and "a kind of Conundrum Castle to be sure".[9]

The last and principal acquisition was that of Toftfield (afterwards named Huntlyburn), purchased in 1817. The new house was then begun and completed in 1824.[4]

The general ground-plan is a parallelogram, with irregular outlines, one side overlooking the Tweed; and the style is mainly the Scottish Baronial. With his architects William Atkinson and Edward Blore Scott was a pioneer of the Scottish Baronial style of architecture: the house is recognized as a highly influential creation with themes from Abbotsford being reflected across many buildings in the Scottish Borders and beyond.[10]

The manor as a whole appears as a "castle-in-miniature", with small towers and imitation battlements decorating the house and garden walls.[11] Into various parts of the fabric were built relics and curiosities from historical structures, such as the doorway of the old Tolbooth in Edinburgh.[4]

Scott collected many of these curiosities to be built into the walls of the South Garden, which previously hosted a colonnade of gothic arches along the garden walls. Along the path of the former colonnade sits the remains of Edinburgh's 15th century Mercat Cross and several examples of classical sculpture.[12]

The estate and its neo-Medieval features nod towards Scott's desire for a historical feel, but the writer ensured that the house would provide all the comforts of modern living. As a result, Scott used the space as a proving-ground for new technologies. The house was outfitted with early gas lighting and pneumatic bells connecting residents with servants elsewhere in the house.[13]

Scott had only enjoyed his residence one year when (1825) he met with that reverse of fortune which involved the estate in debt. In 1830, the library and museum were presented to him as a free gift by the creditors. The property was wholly disencumbered in 1847 by Robert Cadell, the publisher, who cancelled the bond upon it in exchange for the family's share in the copyright of Sir Walter's works.[4]

Scott's only son Walter did not live to enjoy the property, having died on his way from India in 1847. Among subsequent possessors were Scott's grandson Walter Scott Lockhart (later Walter Lockhart Scott, 1826–1853), his younger sister Charlotte Harriet Jane Hope-Scott (née Lockhart) 1828–1858, J. R. Hope Scott, QC, and his daughter (Scott's great-granddaughter), the Hon. Mrs Maxwell Scott.[4]

The house was opened to the public in 1833, but continued to be occupied by Scott's descendants until 2004. The last of his direct descendants to hold the Lairdship of Abbotsford was his great-great-great-granddaughter Dame Jean Maxwell-Scott (8 June 1923 – 5 May 2004). She inherited it from her elder sister Patricia Maxwell-Scott in 1998. The sisters turned the house into one of Scotland's premier tourist attractions, after they had to rely on paying visitors to afford the upkeep of the house. It had electricity installed only in 1962.

Dame Jean was at one time a lady-in-waiting to Princess Alice, Duchess of Gloucester, patron of the Dandie Dinmont Club, a breed of dog named after one of Sir Walter Scott's characters; and a horse trainer, one of whose horses, Sir Wattie, ridden by Ian Stark, won two silver medals at the 1988 Summer Olympics.[14]

On Dame Jean's death the Abbotsford Trust was established to safeguard the estate.[5]

In 2005, Scottish Borders Council considered an application by a property developer to build a housing estate on the opposite bank of the River Tweed from Abbotsford, to which Historic Scotland and the National Trust for Scotland objected.[15][16] There have been modifications to the proposed development, but it is still being opposed in 2020.[17]

Sir Walter Scott rescued the "jougs" from Threave Castle in Dumfries and Galloway and attached them to the castellated gateway he built at Abbotsford.[18]

Tweedbank railway station is located near to Abbotsford.

Miscellaneous

editAbbotsford gave its name to the Abbotsford Club, founded by William Barclay Turnbull in 1833 or 1834 in Scott's honour, and a successor to the Bannatyne and Maitland Clubs. It was a text publication society, which existed to print and publish historical works connected with Scott's writings. Its publications extended from 1835 to 1864.[4]

In August 2012, a new Visitor Centre opened at Abbotsford which houses a small exhibition, gift shop and Ochiltree's café with views over the house and grounds. The house re-opened to the public after extensive renovations in July 2013.

In 2014 it won the European Union Prize for Cultural Heritage / Europa Nostra Award for its then recent conservation project.[19][20]

-

Abbotsford as seen from the gardens

-

The walled garden

-

The orangerie

-

Statue of Morris: a character from Scott's novel Rob Roy-

See also

editNotes

edit- ^ James C. Corson, Notes and Index to Sir Herbert Grierson's Edition of the Letters of Sir Walter Scott (Oxford, 1979), pp. 343–344.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland LB15104.

- ^ Historic Environment Scotland GDL00001.

- ^ a b c d e f Chisholm 1911.

- ^ a b "Abbotsford – The Home of Sir Walter Scott". Abbotsford – The Home of Sir Walter Scott. Retrieved 16 October 2020.

- ^ "Torrs pony cap". Museum of Scotland. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ "Woodrae Castle: Cross Slab(S) (Pictish), Pictish Symbol Stone(S) (Pictish)". Canmore. Retrieved 25 July 2018.

- ^ Grierson, op. cit., 8.129: Scott to John Richardson, [November–December 1823].

- ^ The Journal of Sir Walter Scott, ed. W. E. K. Anderson (Oxford, 1972), 11: 7 January 1828.

- ^ Buck, Michael (1 November 2013). "Early Planning at Abbotsford, 1811–12: Walter Scott, William Stark and the Cottage that Never Was". Architectural Heritage. 24: 41–65. doi:10.3366/arch.2013.0045.

- ^ Irving, Gordon (July 1971). "Sir Walter Scott's Abbotsford". The Christian Science Monitor: 13 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Russell, Vivian (10 October 2003). "The ugliest place on Tweedside". The Daily Telegraph. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 20 November 2018.

- ^ Rigney, Ann (2007). "Abbotsford: Dislocation and Cultural Remembrance". Writers' Houses and the Making of Memory. 1: 76–77 – via ProQuest.

- ^ Sydney Morning Herald 2004, p. 32.

- ^ English, Shirley (19 May 2005). "After 200 years Scott house leaves family". The Times. London. Retrieved 22 September 2017.

- ^ Fairburn, Robert (6 December 2005), "Housing plan put on hold", The Scotsman, archived from the original on 16 May 2007

- ^ "Campaigners keep up opposition". The Southern Reporter. 30 March 2020. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- ^ Napier 1897, p. 153.

- ^ "Europa Nostra". Europa Nostra. Retrieved 3 February 2016.

- ^ "European Commission – PRESS RELEASES – Press release – Winners of 2014 EU Prize for Cultural Heritage / Europa Nostra Awards announced". Europa (web portal). Retrieved 3 February 2016.

References

edit- Historic Environment Scotland. "ABBOTSFORD INCLUDING HOUSE, WALLED GARDENS AND COURTYARDS, CONSERVATORY, BOTHIES, GAME LARDER, ICE HOUSE, TERRACES, GATE LODGE, BOUNDARY WALLS, GARDENER'S COTTAGE, STABLE BLOCK, GARDEN STATUARY AND ALL OTHER ANCILLARY STRUCTURES (Category A Listed Building) (LB15104)". Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- Historic Environment Scotland. "ABBOTSFORD (GDL00001)". Retrieved 26 February 2019.

- Napier, George G. (1897), The Home and Haunts of Sir Walter Scott, Bart, Glasgow: James Maclehose, p. 153

- "Obituary of Dame Jean Maxwell-Scott", The Sydney Morning Herald, p. 32, 13 July 2004

Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Abbotsford". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 1 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press.

External links

editMedia related to Abbotsford House at Wikimedia Commons

- Abbotsford – The Home of Sir Walter Scott – official site

- RCAHMS / CANMORE site record for Abbotsford

- Edinburgh University Library

- Abbotsford (by W S Crockett – 1904 illustrated book pub. A & C Black)

- Abbotsford and Newstead Abbey by Washington Irving, from Project Gutenberg

- Texts on Wikisource:

- Washington Irving, "Abbotsford", in Abbotsford and Newstead Abbey

- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I (9th ed.). 1878. p. 26.

- "Abbotsford". The Nuttall Encyclopædia. 1907.

- "Abbotsford". The New Student's Reference Work. 1914.

- "Abbotsford". Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.