This article needs additional citations for verification. (October 2020) |

Cranhill is an inner city district and housing scheme in the north east of Glasgow, Scotland. Cranhill was developed from public funding in the early 1950s and was originally, chiefly composed of four-storey tenement blocks surrounding a patch of grassland, which became Cranhill Park. Later development saw the building of three tower blocks (locally, high-flats), surrounded by rows of terraced maisonettes. In more recent years, a number of semi-detached and detached homes have been built. The area also hosts some shops, two primary schools and nurseries, a community centre and the Cranhill water tower.

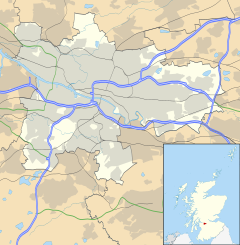

| Cranhill | |

|---|---|

Location within Glasgow | |

| Population | 4,600 (2019)[1] |

| OS grid reference | NS643656 |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area |

|

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | GLASGOW |

| Postcode district | G33 3 |

| Dialling code | 0141 |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

| UK Parliament | |

| Scottish Parliament | |

Infamous for its illegal drug trade and anti-social youth culture, Cranhill was often dubbed "Smack City" in the media. The community was redeveloped from the late 1990s, although unemployment stood at 50% as of 2009.[2][3]

History

editCranhill was built in the early 1950s on the eastern outskirts of the city to alleviate the post-war housing shortage,[4] like other similar publicly funded housing estates. Unlike the much larger housing schemes of Castlemilk, Drumchapel, Easterhouse and Pollok, Cranhill was relatively compact, yet still dense, due to the large number of tenements, maisonettes and tower blocks; the maisonettes were demolished in the late 1990s.

Location and surrounding areas

editCranhill is located in the north-east of the city with High Carntyne to the west (separated by Ruchazie Road), Springboig and Carntyne to the south (separated by the A8 Edinburgh Road), Queenslie to the east (separated by Stepps Road) and Ruchazie to the north (separated by the Monkland Canal, now the M8 motorway).[5] Most of the streets are named after Scottish lighthouses and include Crowlin Crescent, Gantock Crescent, Lamlash Crescent, Monach Road, Skerryvore Road, Startpoint Street, Strone Road and Toward Road. Longstone and Langness Roads and Fastnet are geographical exceptions (Longstone being located in the Farne Islands off the coast of England, Langness Lighthouse on the Isle of Man and Fastnet Rock off the southern coast of Ireland). The main street, running east–west through the entire estate, is Bellrock Street.

Housing

editThe housing stock consisted mostly of four-storey tenement blocks divided into common 'closes', each with eight flats with the end close in each street called a "T" close with 4 flats. The gap between two adjacent "T-closes" was known as a 'gable-end', which in essence was simply a gap between two buildings and normally led to a communal area to the back of the buildings and was the common location for storing rubbish bins. Other types included three tower blocks, locally known as 'the multis' or the 'high flats', a number of terraced maisonettes and a variety of pseudo sandstone (concrete blocks) four-in-a-block cottage flats.

Most of the flats were typical family accommodation of the time, containing a kitchen, bathroom/toilet, two or three bedrooms and a living room. Many of them had balconies or verandas overlooking the street and all were a vast improvement on living conditions in the old Glasgow slum tenements. For many of the families who moved in, this was their first access to green fields and nearby farms, and the playing areas were paradise compared to the rat-infested back-courts which the children had formerly suffered. Nevertheless, a favourite play area was the 'Sugarolly Mountains', substantial hills made from chemical tailings dumped by the side of the canal on the site now occupied by the high flats (and featured in the lyrics of Jim Diamond). No-one knew what they were made of, but the rainwater puddles were green. Even the canal itself was an attraction, given that the next-nearest 'recreational' water was either at Alexandra Park or Hogganfield Loch.

Amenities

editAs the city became established and the community grew, amenities were put in place. Bus routes were extended through the scheme to make it easier for people to travel for work or pleasure, to the City Centre or the nearby shopping areas of Shettleston and Dennistoun. Other basic needs were served with the establishment of three local shopping parades.

As well as the shops, local people were served by mobile street traders with vans and lorries selling foodstuffs, coal and paraffin oil, sweets and soft drinks, ice cream and even fish and chips. In the evenings one could hear the cry of Dalzeil's Bakeries van man shouting "roells!" (bread rolls). Candy apples and 'whelks' (actually periwinkles) could be obtained while rag-merchants would shout 'any old rags' or 'Delft (crockery) for rags' from horsedrawn or hand carts. Today, the only surviving mobile service is the 'ice cream van'.

The first primary schools to be erected were small metal constructions but, at its peak, Cranhill had five primary schools: Lamlash, St Giles RC (the tin part of which was originally used as an annexe of Cranhill Sec), St Elizabeth Seton RC (originally St Modans RC Annex), the larger brick-built Milncroft (including the Toward Rd annex) and St Modans RC. Milncroft was demolished in 2006 and St Modans RC in March 2007. All five original primary schools are now closed and demolished. The two original nursery schools, Bellrock Nursery and Lamlash Nursery, are now also closed. Two new primary schools, Cranhill Primary and St Maria Goretti's RC Primary, were built in 2005/2006, the former on the site of the demolished Milncroft. Lamlash nursery school is now located within St Maria Goretti's Primary school and Bellrock nursery school is located within Cranhill Primary School.

As the children grew older, local secondary schools were needed, the first being Lightburn Secondary across the Edinburgh Rd in Torphin Crescent, Greenfield. With the construction of Cranhill Secondary in Startpoint St, the Torphin Crescent building became St Gregory's RC Secondary to meet the needs of the Roman Catholic population. Some time later, a new St Gregory's was built on waste land at Crowlin Cres in Cranhill and the Torphin Crescent was renamed again, as St Andrews RC Secondary. At its peak, Cranhill Secondary had a roll of some 1300, but both secondaries in Cranhill were razed in the early 1990s and replaced by private housing estates.

Two churches were built: Cranhill (Church of Scotland) Parish Church and St Maria Goretti's RC Church. There were two Boy Scout troops, the 68th Glasgow and the 158th Glasgow, a Boys' Brigade troop, the 150th, and a Girls' Brigade company, the 63rd. The Tenants' Association hall provided an early focus for social events and a Community Centre was opened around 1980.

Cranhill Park was built in the centre of the scheme and became the heart (and lungs) of the community. It featured an 18-hole pitch-and-putt course (famous for its sloping terrain), tennis courts and a bowling green. An annual carnival was held, with a visiting fairground and food outlets. A favourite amongst local children was free miniature loaves of bread distributed by a local bakery. The carnival, however, was stopped in the mid-1980s due to ignored safety regulations which led to some serious accidents, including a near fatal head injury of a 3-year-old child.

The Cranhill Credit Union was set up by John Kerr, Ellen Kerr, Helen Kane MBE and other committed members of the community in the late 1970s. This was modelled on Scotland's first credit union, the Western Credit Union (now Drumchapel Credit Union) established by Bert Mullen in 1970.

The Cranhill Arts Project, possibly better known to more non-residents than to locals, goes from strength to strength, but the most famous local landmark is the Cranhill Water Tower, at the corner of Stepps Rd and Bellrock St. One of several huge elevated storage tanks built to provide high-volume, high-pressure storage, Cranhill Water Tower is unique in having a square concrete tank, in contrast to its cylindrical neighbours in Garthamlock and elsewhere. At night, the structure was illuminated a vibrant green with white spotlights shining from the base of the tank down to the ground. Several wire sculptures of sirens by Andy Scott have been placed around the base of the tower.

Notable residents

editNotable current and former residents include actor Billy Boyd of The Lord of the Rings, footballers Jim and Joe Smith of Newcastle, Aberdeen and Scotland, Kenny Aird of St Johnstone and comedy actor Gerard Kelly. Brothers Angus Young and Malcolm Young lived in Cranhill before they moved to Australia, where they formed AC/DC. George Young, Angus and Malcolm's older brother, also found fame with the 60s group Easybeats. Pat Nevin, soccer pundit and former Scotland player, attended Saint Gregory's Secondary School which later became Saint Andrew's Secondary school. Politician Adam Ingram lived in Skerryvore Road at the bottom of the lane and Glasgow Boy artist Adrian Wiszniewski was also a Cranhill resident. Junior Campbell from the sixties band The Marmalade and who also wrote the music for Thomas the Tank Engine lived in nearby Springboig, but ran his schoolboy "paper round" from the Glasgow Evening Times/Citizen van drop at the infamous Cranhill Water Tower. Archy Kirkwood (Sir Archibald Johnstone Kirkwood, Baron Kirkwood of Kirkhope) long-standing Liberal Democrat MP, then knighted, then elevated to the House of Lords lived and was educated in Cranhill. He played in a pop group (The Aztecs) in the same locations and at the same time as The Gaylords (early Marmalade) at two nearby Springboig venues; both groups could hear each other playing next door, alternating Saturdays at the YMCA and the "Shack". Kirkwood lived in Crowlin Crescent.

Cranhill today

editMost of the original housing stock has been demolished to make way for 'back-and-front-door' houses and a private housing scheme and supermarket now occupy the site of the former Cranhill Secondary School. However, the original flats are retained in some of the streets around the Park, as are the shops at Lamlash Cres. Two new schools and two new nurseries have been built on Newhaven Road. The local Park is now a protected habit for water voles, and is the only known location for these voles in mainland Scotland. The Community Centre has been replaced by a children's centre called 'The Beacon' which is within Cranhill Park.

The 'backfields' is now a construction site for semi-detached homes.

There is also an active Community Council consisting of several committed residents who aim to deal with issues affecting the Cranhill neighbourhood, and it holds regular monthly meetings open to all interested residents with these normally taking place every fourth Wednesday of the month at 7pm in the Community Centre.

In 2016, Glasgow City Council outlined masterplans for the development of the Greater Easterhouse area (including Cranhill) over the next 20 years.[6][7]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ Glasgow City, Scottish Government Statistics [seven 2011 data zones: Craigend and Ruchazie - 01, Cranhill, Lightburn and Queenslie South - 01, 02, 05, 06, 07, 08]

- ^ "Community appalled by elderly woman's murder". The Herald. 31 December 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ "Cranhill has a new lease of life after cleaning up its act". Evening Times. 30 April 2009. Retrieved 22 October 2020.

- ^ "Buildings and Cityscape; Council Housing". The Glasgow Story. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "M8 Motorway". The Glasgow Story. Retrieved 2 October 2017.

- ^ "Easterhouse the latest Glasgow district to be transformed". The Scotsman. 28 September 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2018.

- ^ "Council report outlines exciting vision of the future transformation of Easterhouse". Glasgow City Council. 27 September 2016. Retrieved 23 July 2018.