Davis Station, commonly called Davis, is one of three permanent bases and research outposts in Antarctica managed by the Australian Antarctic Division (AAD). Davis is situated on the coast of Cooperation Sea in Princess Elizabeth Land, Ingrid Christensen Coast in the Australian Antarctic Territory, a territory claimed by Australia. Davis lies in an Antarctic oasis, a mostly ice-free area known as the Vestfold Hills.

Davis Station | |

|---|---|

Antarctic base | |

Davis Station, pictured in 2005. | |

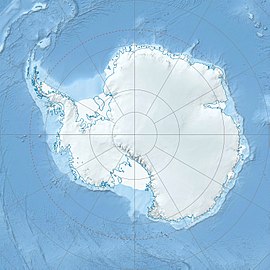

Location of Davis Station in Antarctica | |

| Coordinates: 68°34′36″S 77°58′03″E / 68.576667°S 77.9675°E | |

| Country | |

| Territory | Australian Antarctic Territory |

| Subdivision | Princess Elizabeth Land |

| Administered by | Australian Antarctic Division |

| Established | 13 January 1957 |

| Named for | Captain John King Davis |

| Elevation | 27 m (89 ft) |

| Population (2017)[1] | |

| • Summer | 91 |

| • Winter | 17 |

| Time zone | UTC+7 (DAVT) |

| UN/LOCODE | AQ DAV |

| Type | All year-round |

| Period | Annual |

| Status | Operational |

| Activities | List

|

| Facilities[2] | List

|

| Website | aad.gov.au |

Davis Plateau Ski Landing Area | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Summary | |||||||||||

| Airport type | Private | ||||||||||

| Operator | Australian Antarctic Division | ||||||||||

| Location | Davis Station - Whoop Whoop | ||||||||||

| Elevation AMSL | 1,528 ft / 466 m | ||||||||||

| Coordinates | 68°28′09″S 78°52′11″E / 68.4692°S 78.8696°E | ||||||||||

| Map | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Runways | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

Davis was named in honour of Captain John King Davis.[5][6]

Davis was listed on the Register of the National Estate on 26 October 1999 and has been included on the Commonwealth Heritage List as an indicative place, due to the condition of buildings and structures that varies from no longer exists/demolished due to poor condition, through to very good condition.[7]

Purpose

editDavis is a base for scientific research programs including the study of viruses and bacteria using molecular genetic techniques in glacial lakes, the impact of environmental change and pollution on Antarctic marine ecosystems, atmospheric research, measuring algae growth as an important food source for tiny marine herbivores such as zooplankton, the impact of climate change, including the increasing carbon dioxide concentrations on marine microbes and, together with researchers at Casey, the study of the Law Dome, the bedrock geology and structure of the East Antarctic ice sheet.[8][9]

History

editThe first recorded sighting of the coastline now occupied by Davis Station was on 9 February 1931, during the second British Australian and New Zealand Antarctic Research Expedition (BANZARE) voyage aboard Discovery. Sir Douglas Mawson and Flight Lieutenant Stuart Campbell sighted the Antarctic continent from a seaplane and named the high land to the southeast Princess Elizabeth Land.[5]

The first recorded landing in the region was made in 1935 by the Norwegian whaler Captain Klarius Mikkelsen in the vessel Thorshavn. Mikkelsen named the hills after the Vestfold province of Norway, on the western side of Oslo Fjord, which he considered it resembled, and where the Christensen company's headquarters was located, at the town of Sandefjord.[5]

On 20 February 1935, together with his wife and seven crew members (including the ship's dentist, Lief Sørsdal), Mikkelsen landed in a small bay on an unnamed island at the northern end of the Vestfold Hills. Mrs Caroline Mikkelsen was the first woman to set foot on the Antarctic continent and the party raised the Norwegian flag on an improvised flagpole and built a rock cairn to mark the site. This cairn was found by members of the Australian National Antarctic Research Expeditions (ANARE) in 1960 but was lost for many years until its rediscovery in 1995. (As an interesting aside, Caroline Mikkelsen was still living and received word of the rediscovery of the original flagpole.) Captain Mikkelsen named the area "Ingrid Christensen Land" after the wife of the ship's owner, Lars Christensen. Mrs Christensen was later to land in Antarctica herself - on 30 January 1937, at Scullin Monolith (which the Norwegians called Klarius Mikkelsen Mountain).

The Thorshavn and Klarius Mikkelsen, along with Lars Christensen, were back in the Vestfold Hills area in the 1936–37 summer. An area to the immediate north of the Vestfold Hills was used as a take-off and landing area for a seaplane, from which oblique aerial photos were taken for mapping purposes. The first map of the Vestfold Hills, derived from this imagery, was published after World War II.[5]

The next recorded visitors to the area were the American explorer Lincoln Ellsworth and his Australian aircraft pilot and observer Sir Hubert Wilkins, in Ellsworth's ship Wyatt Earp. Despite Wilkins' protestations that Mawson had already claimed the area for Australia, Ellsworth planned to lodge a counter claim for America. In response to this, Wilkins took pre-emptive action and made two landings. The first was on one of the Rauer Islands, at 68° 46' South, 77° 50' East on 8 January 1939, and the second on a rocky outcrop at 68° 22' South 70° 33' East on 11 January 1939. At both of these locations he deposited decrees recognising Australia's right to ". . . administrate . . . those parts of His Majesty's dominions in the Antarctic Seas". Along with the decree he left a copy of the famous Australian geographical magazine 'Walkabout". Of three such sites, only the northern cairn has been located and hence the name "Walkabout Rocks".[5]

During the U.S. Antarctic explorations that formed a part of "Operation Highjump" in 1947, USS Currituck visited the area, but no landing took place. As part of Operation Highjump, the Vestfolds and surrounding area were extensively photographed from the air.[5]

The first ANARE landing in the Vestfold Hills was made on 3 March 1954 by Phillip Law, Peter Shaw, John Hansen, Arthur Gwynn and R. Thompson. They raised the Australian flag at Law Cairn, to the north of Davis Station, but had to return to their ship soon after due to deteriorating weather.[5]

On 12 January 1956, members of the Soviet Antarctic Expedition landed on the Ingrid Christensen Coast, in preparation for the International Geophysical Year (1957–58). The Soviets did not stay for long but even today the Russian presence is betrayed by some distinctively Russian names on the map (Lakes Lebed, Zvezda and Druzhby among them) They later established their base at Mirny Station, some 350 kilometres (220 mi) to the east of Davis.[5]

As Phillip Law recalled during a short visit to Davis on 11 January 1998, it was felt that if Australia did not establish a base in the Vestfold Hills the Russians would, and so in 1955 the Australian Government announced that a new station would be established in the Vestfold Hills.[5]

A further exploratory visit was made by ANARE in January 1955 that involved two teams traversing much of the Vestfold Hills. During January 1957, an ANARE party led by Dr Phillip Law sailing on the Kista Dan attempted to locate a suitable site for the station. This proved difficult due to a lack of good ship anchorages and a scarcity of fresh water sources. On 12 January, after two days of attempting to find a suitable site, a last-minute decision was made to locate the station on a small rocky plateau located above a black sandy beach. Unloading began immediately and, on 13 January 1957, a small ceremony was held to officially open the new station. It was named Davis "to honour Captain John King Davis, a famous Antarctic navigator and captain . . . at present . . . living in Melbourne, a member of the ANARE Planning Committee". (Law's address on the day). After the ceremony, unloading recommenced and continued until 20 January when Kista Dan sailed. Kista Dan made a return visit to Davis later dropping off dogs and one more expeditioner.[5]

Bob Dingle, Alan Hawker, Nils Lied, Bill Lucas and Bruce Stinear made up the first party to winter in the Vestfold Hills. The party was not completely isolated however as Auster aircraft flew between Mawson Station and Davis several times that year exchanging personnel and supplies.[5]

Davis was temporarily closed on 25 January 1965 to make resources available for the rebuilding of Casey Station. It was reopened on 15 February 1969 and has been continuously occupied since that time. The original small huts ("dongas") fell into disuse and disrepair from the late 1970s / early 1980s, with a major rebuilding program.[5]

Davis has become the busiest of Australia's Antarctic stations supporting a wide variety of scientific research in both the local and surrounding areas during the summertime. During the wintertime, the principal research activity is Upper Atmospheric Physics.

Logistics

editDavis is 4,838 km (3,006 mi) from Hobart, the AAD's main supply hub for Antarctic operations, and 4,716 km (2,930 mi) from Fremantle.[10]

Air transport

editIn early summer when sea ice conditions are most favourable, a ski landing area (SLA) is constructed adjacent to Davis. As sea ice conditions progressively worsen over summer, operations are moved first to the Plough Island SLA, 6 km north of Davis,[11] and in late summer to Whoop Whoop,[12] a field camp 40 km east of Davis on the inland ice plateau, called the Davis Plateau ice SLA.[13] The SLA requires frequent maintenance by snow grooming, and as it is not accessible by ground vehicles, passengers and cargo are transported on to Davis by helicopter.[3]

Earth station

editDavis is the first Antarctic Earth stations in Australia, with the first satellite tracking antenna ANARESAT for communications installed in March 1987.[14] There is also a Bureau of Meteorology satellite tracking station for a weather satellite, Himawari-8 located there.[15]

After numerous upgrades since installation, the ANARESAT facility is able to provide the station with a 9 Mbps link back to the mainland. This allows for the real time transfer of scientific data as well as support for telemedicine and video calls for expeditioners.

Climate

editDavis Station experiences an tundra climate (Köppen ET); the temperature is moderated by its proximity to the Southern Ocean.

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °C (°F) | 13.0 (55.4) |

10.0 (50.0) |

4.3 (39.7) |

4.2 (39.6) |

2.0 (35.6) |

2.0 (35.6) |

0.8 (33.4) |

1.0 (33.8) |

0.3 (32.5) |

1.9 (35.4) |

8.0 (46.4) |

11.0 (51.8) |

13.0 (55.4) |

| Mean daily maximum °C (°F) | 3.2 (37.8) |

−0.2 (31.6) |

−5.6 (21.9) |

−10.3 (13.5) |

−12.5 (9.5) |

−12.5 (9.5) |

−14.3 (6.3) |

−14.2 (6.4) |

−12.8 (9.0) |

−9.0 (15.8) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

2.4 (36.3) |

−7.3 (18.9) |

| Mean daily minimum °C (°F) | −1.2 (29.8) |

−4.6 (23.7) |

−10.9 (12.4) |

−16.1 (3.0) |

−18.8 (−1.8) |

−18.7 (−1.7) |

−20.6 (−5.1) |

−20.8 (−5.4) |

−19.7 (−3.5) |

−15.3 (4.5) |

−7.5 (18.5) |

−2.2 (28.0) |

−13.0 (8.6) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −14.0 (6.8) |

−15.0 (5.0) |

−27.6 (−17.7) |

−41.8 (−43.2) |

−39.0 (−38.2) |

−40.1 (−40.2) |

−39.0 (−38.2) |

−41.3 (−42.3) |

−38.3 (−36.9) |

−31.0 (−23.8) |

−22.4 (−8.3) |

−10.7 (12.7) |

−41.8 (−43.2) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 1.8 (0.07) |

3.8 (0.15) |

9.1 (0.36) |

10.1 (0.40) |

9.9 (0.39) |

9.1 (0.36) |

8.2 (0.32) |

6.8 (0.27) |

5.4 (0.21) |

4.5 (0.18) |

2.2 (0.09) |

1.9 (0.07) |

72.8 (2.87) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 0.2 mm) | 2.2 | 3.2 | 6.5 | 6.5 | 6.3 | 5.4 | 4.9 | 4.9 | 4.6 | 4.2 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 53 |

| Mean monthly sunshine hours | 285.2 | 166.7 | 99.2 | 69.0 | 21.7 | 0.0 | 9.3 | 58.9 | 123.0 | 170.5 | 234.0 | 303.8 | 1,541.3 |

| Source: Bureau of Meteorology[16] | |||||||||||||

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b Antarctic Station Catalogue (PDF) (catalogue). Council of Managers of National Antarctic Programs. August 2017. p. 31. ISBN 978-0-473-40409-3. Archived (PDF) from the original on 22 October 2022. Retrieved 16 January 2023.

- ^ "Living at Davis". Australian Antarctic Division. Department of the Environment, Australian Government. 6 November 2002. Retrieved 11 July 2016.

- ^ a b This week at Davis: 18 January 2019 Australian Antarctic Division. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "Davis Plateau Skiway". Airport Nav Finder. Retrieved 16 October 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l "Davis station: a brief history". History of Australian Antarctic stations. Australian Antarctic Division. 17 June 2002. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ Australian Philatelic Bulletin, Vol. 16, p. 28

- ^ "Indicator: AATH-07 Condition of scientific research stations - survey of Davis Station". Department of the Environment. Australian Government. 2006. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Davis science". Australian Antarctic Division. 17 August 2006. Retrieved 8 July 2016.

- ^ "Industrial Buildings". 16 January 2017. Thursday, 27 September 2018

- ^ Stations, Australian Antarctic Division. Retrieved 28 January 2023.

- ^ "Intracontinental ski landing area locations". Australian Antarctic Program. 26 May 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ Latest Weather Observations for Whoop Whoop Australian Government, Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Intracontinental ski landing area locations Australian Antarctic Division. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "Australian Antarctic Magazine Issue - 2" (PDF). www.antartica.gov.au. Australian Antarctic Division. 1 September 2001. Archived from the original (PDF) on 10 August 2019. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

A team of eight OTC engineers, technicians and riggers installed and commissioned the first satellite earth station at Davis in March 1987.

- ^ "About environmental satellites". www.bom.gov.au. Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 26 April 2017.

In order to access this meteorological data the Bureau of Meteorology has high bandwidth internet, as well as satellite data reception sites at Melbourne, Darwin and Perth, as well as Casey and Davis stations in Antarctica.

- ^ "Climate Statistics for Davis". Climate statistics for Australian locations. Bureau of Meteorology. Retrieved 23 October 2012.