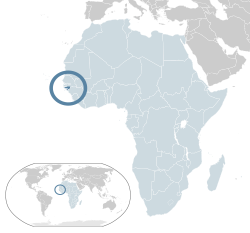

Guinea-Bissau,[a] officially the Republic of Guinea-Bissau,[b] is a country in West Africa that covers 36,125 square kilometres (13,948 sq mi) with an estimated population of 2,026,778. It borders Senegal to its north and Guinea to its southeast.[10]

Republic of Guinea-Bissau | |

|---|---|

| Motto: Unidade, Luta, Progresso "Unity, Struggle, Progress" | |

| Anthem: Esta É a Nossa Pátria Bem Amada "This is Our Beloved Homeland" | |

| Capital and largest city | Bissau 11°52′N 15°36′W / 11.867°N 15.600°W |

| Official languages | Portuguese |

| Spoken languages | |

| Ethnic groups (2019)[1] | |

| Religion |

|

| Demonym(s) | Bissau-Guinean[5] Guinean |

| Government | Unitary semi-presidential republic |

| Umaro Sissoco Embaló | |

| Rui Duarte de Barros | |

| Legislature | National People's Assembly |

| Independence from Portugal | |

• Declared | 24 September 1973 |

• Recognized | 10 September 1974 |

| Area | |

• Total | 36,125 km2 (13,948 sq mi) (134th) |

• Water (%) | 22.4 |

| Population | |

• 2023 estimate | 2,078,820[6] (150th) |

• Density | 46.9/km2 (121.5/sq mi) (154th) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2021) | medium inequality |

| HDI (2022) | low (179th) |

| Currency | West African CFA franc (XOF) |

| Time zone | UTC (GMT) |

| Drives on | Right |

| Calling code | +245 |

| ISO 3166 code | GW |

| Internet TLD | .gw |

Guinea-Bissau was once part of the kingdom of Kaabu,[11] as well as part of the Mali Empire.[11] Parts of this kingdom persisted until the 18th century, while a few others had been under some rule by the Portuguese Empire since the 16th century. In the 19th century, it was colonised as Portuguese Guinea.[11] Portuguese control was restricted and weak until the early 20th century, when its pacification campaigns solidified Portuguese sovereignty in the area. The final Portuguese victory over the last remaining bastion of mainland resistance came in 1915, with the conquest of the Papel-ruled Kingdom of Bissau by the Portuguese military officer Teixeira Pinto and the Wolof mercenary Abdul Injai.[12]

The Bissagos, islands off the coast of Guinea-Bissau, were officially conquered in 1936, ensuring Portuguese control of both the mainland and islands of the region.[13]

Upon independence, declared in 1973 and recognised in 1974, the name of its capital, Bissau, was added to the country's name to prevent confusion with Guinea (formerly French Guinea). Guinea-Bissau has had a history of political instability since independence. The current president is Umaro Sissoco Embaló, who was elected on 29 December 2019.[14]

About 2% of the population speaks Portuguese, the official language, as a first language, and 33% speak it as a second language. Guinea-Bissau Creole, a Portuguese-based creole, is the national language and also considered the language of unity. According to a 2012 study, 54% of the population speak Creole as a first language and about 40% speak it as a second language.[15] The remainder speak a variety of native African languages.

The nation is home to numerous followers of Islam, Christianity, and multiple traditional faiths.[16][17] The country's per capita gross domestic product is one of the lowest in the world.

Guinea-Bissau is a member of the United Nations, African Union, Economic Community of West African States, Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, Community of Portuguese Language Countries, Organisation internationale de la Francophonie, and the South Atlantic Peace and Cooperation Zone. It was also a member of the now-defunct Latin Union.

History

editPre-European contact

editThe deep history of what is now Guinea-Bissau is poorly understood by historians. The earliest inhabitants were the Jola, Papel, Manjak, Balanta, and Biafada peoples.[citation needed] Later the Mandinka and Fulani migrated into the region, in the 13th and 15th centuries, respectively. They pushed the earlier inhabitants towards the coast and onto the Bijagos islands.[18][19]: 20

The Balanta and Jola had weak or non-existent institutions of kingship but emphasised decentralization, with power invested in heads of villages and families.[19]: 64 The Mandinka, Fula, Papel, Manjak, and Biafada chiefs were vassals to kings. The customs, rites, and ceremonies varied, but nobles commanded all the major positions, including the judicial system.[19]: 66–67, 73, 227 Social stratification was seen in the clothing and accessories of the people, in housing materials, and in transportation options.[19]: 77–8 Trade was widespread between ethnic groups. Items traded included pepper and kola nuts from the southern forests; kola nuts, iron, and iron utensils from the savannah-forest zone; salt and dried fish from the coast; and Mandinka cotton cloth.[20]: 4

Kingdom of Bissau

editAccording to oral tradition, the Kingdom of Bissau was founded by the son of the king of Quinara (Guinala), who moved to the area with his pregnant sister, six wives, and subjects of his father's kingdom.[21] Relations between the kingdom and the Portuguese colonisers were initially warm, but deteriorated over time.[22]: 55 The kingdom strongly defended its sovereignty against the Portuguese 'Pacification Campaigns', defeating them in 1891, 1894, and 1904. However, in 1915 the Portuguese under the command of Officer Teixeira Pinto and warlord Abdul Injai fully absorbed the kingdom.[12]

Biafada kingdoms

editThe Biafada people inhabited the area around the Rio Grande de Buba in three kingdoms: Biguba, Guinala, and Bissege.[19]: 65 The former two were important ports with significant lançado communities.[22]: 63, 211 They were subjects of the Mandinka mansa of Kaabu.[22]: 211

The Bijagos

editIn the Bijagos Islands, people of different ethnic origins tended to settle in separate settlements. Great cultural diversity developed in the archipelago.[19]: 24 [22]: 52

Bijago society was warlike. Men were dedicated to boatbuilding and raiding the mainland, attacking the coastal peoples as well as other islands. They believed that at sea they had no king. Women cultivated the land, constructed houses, and gathered and prepared foods. They could choose their husbands, and warriors with the best reputations ranked at the top of respected status. Successful warriors could have many wives and boats, and were entitled to one third of the spoils gained by warriors who used their boats in any expedition.[19]: 204–205

Bijago night raids on coastal settlements had significant effects on the societies attacked. Portuguese traders on the mainland tried to stop the raids, as they hurt the local economy. But the islanders also sold considerable numbers of villagers captured in raids as slaves to the Europeans. With colonisation underway in other parts of Africa and the Americas, demand for workers was high and the Europeans sometimes pushed for more captives to be taken.[19]: 205

The Bijagos were mostly safe from enslavement, as they were out of reach of mainland slave raiders. Europeans avoided having them as slaves. Portuguese sources say the children made good slaves but not the adults, who were likely to commit suicide, lead rebellions aboard slave ships, or escape once reaching the New World.[19]: 218–219

Kaabu

editKaabu was established first as a province of Mali through the conquest in the 13th century of the Senegambia by Tiramakhan Traore, a general under Sundiata Keita. By the 14th century much of Guinea Bissau was under the administration of Mali. It was ruled by a farim kaabu (commander of Kaabu).[23]

Mali declined gradually, beginning in the 14th century. By the early 16th century, the expanding power of Koli Tenguella cut off formerly secure Mali.

Kaabu became an independent federation of kingdoms.[24]: 13 [25] The ruling classes were composed of elite warriors known as the Nyancho (Ñaanco) who traced their patrilineal lineage to Tiramakhan Traore.[26]: 2 The Nyancho were a warrior culture, reputed to be excellent cavalry men and raiders.[24]: 6 The Kaabu Mansaba was seated in Kansala, today known as Gabu, in the eastern Geba region.[20]: 4

The slave trade dominated the economy, and the warrior classes grew rich with imported cloth, beads, metalware, and firearms.[24]: 8 Trade networks with Arabs and others to North Africa were dominant up to the 14th century. In the 15th century, coastal trade with the Europeans began to increase.[20]: 3 In the 17th and 18th centuries an estimated 700 slaves were exported annually from the region, many of them from Kaabu.[20]: 5

In the late 18th century, the rise of the Imamate of Futa Jallon to the east posed a powerful challenge to the animist Kaabu. During the first half of the 19th century, civil war erupted as local Fula people sought independence.[20]: 5–6 This long-running conflict was marked by the 1867 Battle of Kansala; the Fuladu effectively defeated the Kaabu and dominated the area thereafter. But some smaller Mandinka kingdoms survived until their absorption into Portuguese colonies.

European contact

edit15th–16th centuries

editThe first Europeans to reach Guinea-Bissau were the Venetian explorer Alvise Cadamosto in 1455, Portuguese explorer Diogo Gomes in 1456, Portuguese explorer Duarte Pacheco Pareira in the 1480s, and Flemish explorer Eustache de la Fosse in 1479–1480.[27]: 7, 12–13, 16

Although the Portuguese authorities initially discouraged European settlement on the mainland, this prohibition was ignored by lançados and tangomãos, who largely assimilated into indigenous culture and customs.[19]: 140 They ignored Portuguese trade regulations that banned entering the region or trading without a royal licence, shipping out of unauthorised ports, or assimilating into the native community.[19]: 142

After 1520 trade and settlements increased on the mainland, populated by Portuguese and native traders, as well as some Spanish, Genoese, English, French, and Dutch.[19]: 145, 150 The main ports were Cacheu, Bissau, and Guinala. Each river also had such trading centers as Toubaboudougou at their fall lines, the furthest navigable point. These posts traded directly with the peoples of the interior for resources such as gum arabic, ivory, hides, civet, dyes, enslaved Africans, and gold.[19]: 153–160 Local African rulers generally refused to allow Europeans into the interior, to ensure their own control of trade routes and goods.[28]

Disputes became increasingly frequent and serious in the late 1500s as the foreign traders sought to influence the host societies to their benefit.[22]: 74 Meanwhile, the Portuguese monopoly, always leaky, was being increasingly challenged. In 1580 the Iberian Union unified the crowns of Portugal and Spain. Spain's enemies launched attacks on Portuguese possessions in Guinea Bissau and Cape Verde. French, Dutch, and English ships increasingly came to trade with the natives and the independent-minded lançados.[19]: 244–253

17th–18th centuries

editIn the early 17th century the government attempted to force all Guinean trade to go through Santiago, and to promote trade and settlement on the mainland, while restricting the sale of weapons to the locals. These efforts were largely unsuccessful.[19]: 243–4

With the end of the Iberian Union in 1640, King João IV attempted to restrict the Spanish trade in Guinea that had flourished for the previous 60 years. Afro-Portuguese traders and colonists, however, were not in a position to deny the free trade that the African kings demanded, as they had come to rely on European products and goods as necessities.[19]: 261–3

The Portuguese were never able to maintain the monopoly they wanted; the economic interests of the native leaders and Afro-European traders and merchants never aligned with theirs. During this period the power of the Mali Empire in the region was dissipating. The farim of Kaabu, the king of Kassa, and other local rulers began to assert their independence.[19]: 488

In the early 1700s the Portuguese abandoned Bissau and retreated to Cacheu after the captain-major was captured and killed by the local king. They did not return until the 1750s. Meanwhile, the Cacheu and Cape Verde Company shut down in 1706.[22]: xliii

For a brief period in the 1790s, the British tried to establish a foothold on Bolama Island.[29]

Slave trade

editGuinea-Bissau was among the first regions whose people engaged in the Atlantic slave trade. For centuries its warriors had sent captives as slaves to North Africa. While it did not produce the same number of enslaved people to export to the Americas as other regions, the effects were still significant.[30][28]

In Cape Verde, Guinean slaves were instrumental in developing the labor-intensive plantation economy: they cultivated and processed, growing indigo and cotton, and also wove the panos cloth that became a standard currency in West Africa.[18] During the 17th and 18th centuries, thousands of captive Africans were taken from the region every year by Portuguese, French, and British companies. An average of 3000 persons were shipped every year from Guinala alone.[19]: 278 Many of these captives were taken during the Fula jihads and, specifically, the wars between the Imamate of Futa Jallon and Kaabu.[22]: 377

Wars were increasingly waged for the sole purpose of capturing slaves to sell to the Europeans in exchange for imported goods. They resembled man-hunts more than conflicts over territory or political power.[19]: 204, 209 The nobles and kings benefited, while the common people bore the brunt of the raiding and insecurity. If a noble was captured, they were likely to be released, as the captors, whoever they were, would generally accept a ransom in exchange for freeing them.[19]: 229 The relationship between kings and European traders was a partnership, with the two regularly making deals on how the trade was to be conducted, defining who could be enslaved and who could not, and the prices of the slaves. Contemporary chroniclers questioned multiple kings on their part in the slave trade, and noted that they recognised the trade as evil but participated because otherwise the Europeans would not buy any other goods from them.[19]: 230–4

Beginning in the late 18th century, European countries gradually began slowing and/or abolishing the slave trade. Portugal abandoned slavery in 1869 and Brazil in 1888, but a system of contract labor replaced it that was only barely better for the workers.[22]: 377

Colonialism

editUp until the late 1800s, Portuguese control of their 'colony' outside of their forts and trading posts was a fiction. Guinea-Bissau became the scene of increased European colonial competition beginning in the 1860s. The dispute over the status of Bolama was resolved in Portugal's favor through the mediation of U.S. President Ulysses S. Grant in 1870, but French encroachment on Portuguese claims continued. In 1886 the Casamance region of what is now Senegal was ceded to them.[18]

Struggle for independence

editThe African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde (PAIGC) was founded in 1956 under the leadership of Amílcar Cabral. Initially committed to peaceful methods, the 1959 Pidjiguiti massacre pushed the party towards more militarized tactics, leaning heavily on the political mobilization of the peasantry in the countryside. After years of planning and preparing from their base in Conakry, the PAIGC launched the Guinea-Bissau War of Independence on 23 January 1963.[22]: 289

Unlike guerrilla movements in other Portuguese colonies, the PAIGC rapidly extended its control over large portions of the territory. Aided by the jungle-like terrain, it had easy access to borders with neighbouring allies and large quantities of arms from Cuba, China, the Soviet Union, and left-leaning African countries. The PAIGC even managed to acquire a significant anti-aircraft capability in order to defend itself against aerial attack.[22]: 289–90 By 1973, the PAIGC was in control of many parts of Guinea, although the movement suffered a setback in January 1973 when its founder and leader Amilcar Cabral was assassinated.[31] After Cabral's death, party leadership fell to Aristides Pereira, who would later become the first president of the Republic of Cape Verde.

Independence (1973–2000)

editIndependence was unilaterally declared on 24 September 1973, which is now celebrated as the country's Independence Day, a public holiday.[32] The country was formally recognized as independent on 10 September 1974.[33] Nicolae Ceaușescu's Romania was the first country to formally recognise Guinea-Bissau and the first to sign agreements with the African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde.[34][35]

Upon the nation's independence, it declared Esta É a Nossa Pátria Bem Amada as its national anthem. Until 1996, this was shared with Cape Verde, which later adopted its own official national anthem Cântico da Liberdade.[36][37][38][39]

Luís Cabral, brother of Amílcar and co-founder of PAIGC, was appointed the first president of Guinea-Bissau.[28] Independence had begun under the best of auspices. The Bissau-Guinean diaspora had returned to the country en masse. A system of access to school for all had been created. Books were free and schools seemed to have a sufficient number of teachers. The education of girls, previously neglected, was encouraged and a new school calendar, more adapted to the rural world, was adopted.

In 1980, economic conditions deteriorated significantly, leading to general discontent with the government in power. On 14 November 1980, João Bernardo Vieira, known as "Nino Vieira", overthrew President Luís Cabral. The constitution was suspended and a nine-member Military Council of the Revolution, chaired by Vieira, was established. Since then, the country has moved toward a liberal economy. Budget cuts have been made at the expense of the social sector and education.[40]

The country was controlled by the military council until 1984. The first multi-party elections were held in 1994. An army uprising in May 1998 led to the Guinea-Bissau Civil War and the president's ousting in June 1999.[41] Elections were held again in 2000, and Kumba Ialá was elected president.[42]

21st century

editIn September 2003, a military coup was conducted. The military arrested Ialá on the charge of being "unable to solve the problems".[43] After being delayed several times, legislative elections were held in March 2004. A mutiny in October 2004 over pay arrears resulted in the death of the head of the armed forces.[44]

In June 2005, presidential elections were held for the first time since the coup that deposed Ialá. Ialá returned as the candidate for the PRS, claiming to be the legitimate president of the country, but the election was won by former president João Bernardo Vieira, deposed in the 1999 coup. Vieira beat Malam Bacai Sanhá in a run-off election. Sanhá initially refused to concede, claiming that tampering and electoral fraud occurred in two constituencies including the capital, Bissau.[45] Foreign monitors described the elections as "calm and organized", despite some reports of arms entering the country prior to the election and few "disturbances during campaigning", including attacks on government offices by unidentified gunmen.[46]

Three years later, Sanhá's PAIGC won a strong parliamentary majority, with 67 of 100 seats, in the parliamentary election held in November 2008.[47] In November 2008, President Vieira's official residence was attacked by members of the armed forces, killing a guard but leaving the president unharmed.[48]

On 2 March 2009, however, Vieira was assassinated by what preliminary reports indicated to be a group of soldiers avenging the death of the head of joint chiefs of staff, General Batista Tagme Na Wai, who had been killed in an explosion the day before.[49] Vieira's death did not trigger widespread violence, but there were signs of turmoil in the country, according to the advocacy group Swisspeace.[50] Military leaders in the country pledged to respect the constitutional order of succession. National Assembly Speaker Raimundo Pereira was appointed as an interim president until a nationwide election on 28 June 2009.[51] It was won by Malam Bacai Sanhá, against Kumba Ialá as the presidential candidate of the PRS.[52]

On 9 January 2012, President Sanhá died of complications from diabetes, and Pereira was again appointed as an interim president. On the evening of 12 April 2012, members of the country's military staged a coup d'état and arrested the interim president and a leading presidential candidate.[53] Former vice chief of staff, General Mamadu Ture Kuruma, assumed control of the country in the transitional period and started negotiations with opposition parties.[54][55]

The 2014 general election saw José Mário Vaz elected President of Guinea-Bissau. Vaz became the first elected president to complete his five-year mandate. At the same time, he was eliminated in the first round of the 2019 presidential elections, ultimately seeing Umaro Sissoco Embaló emerge as the victor. Embaló, the first president to be elected without the backing of the PAIGC, took office in February 2020.[56][57]

On 1 February 2022, there was an attempted coup d'état to overthrow President Umaro Sissoco Embaló.[58][59][60] On 2 February 2022, state radio announced that four assailants and two members of the presidential guard had been killed in the incident.[61] The African Union and ECOWAS both condemned the coup.[62] Six days after the attempted coup d'état, on 7 February 2022, there was an attack on the building of Rádio Capital FM,[63] a radio station critical of the Bissau-Guinean government;[64] this was the second time the radio station suffered an attack of this nature in less than two years.[63] A journalist working for the station recalled, while wishing to stay anonymous, that one of their colleagues had recognized one of the cars carrying the attackers as belonging to the presidency.[64]

In 2022, Embaló became the first African ruler to visit Ukraine since the Russian invasion of the country in February, meeting with President of Ukraine Volodymyr Zelenskyy.[65]

In 2023, an attempted coup reportedly occurred in the capital, Bissau, leading Embaló to order the dissolution of the opposition-controlled parliament.[66][67] On 11 September 2024, President Umaro Sissoco Embaló announced that he would not seek a second term in the upcoming presidential elections scheduled for November 2025.[68]

Politics

editGuinea-Bissau is a republic.[69] In the past, the government had been highly centralized. Multi-party governance was not established until mid-1991.[69] The president is the head of state and the prime minister is the head of government. From independence in 1974, until Jose Mario Vaz ended his five-year term as president on 24 June 2019, no president successfully served a full five-year term.[56]

At the legislative level, a unicameral Assembleia Nacional Popular (National People's Assembly) is made up of 100 members. They are popularly elected from multi-member constituencies to serve a four-year term. The judicial system is headed by a Tribunal Supremo da Justiça (Supreme Court), made up of nine justices appointed by the president; they serve at the pleasure of the president.[70]

The two main political parties are the PAIGC (African Party for the Independence of Guinea and Cape Verde) and the PRS (Party for Social Renewal). There are more than 20 minor parties.[71]

Foreign relations

editGuinea-Bissau is a founding member state of the Community of Portuguese Language Countries (CPLP), also known as the Lusophone Commonwealth, an international organisation and political association of Lusophone nations where Portuguese is an official language.[72]

Military

editA 2019 estimate put the size of the Guinea-Bissau Armed Forces at around 4,400 personnel and military spending is less than 2% of GDP.[1] In 2018, Guinea-Bissau signed the UN treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons.[73]

Administrative divisions

editGuinea-Bissau is divided into eight regions (regiões) and one autonomous sector (sector autónomo).[74] These, in turn, are subdivided into 37 Sectors.[75] The regions are:[75]

- ^ /ˌɡɪni bɪˈsaʊ/ ⓘ; Portuguese: Guiné-Bissau; Fula: 𞤘𞤭𞤲𞤫 𞤄𞤭𞤧𞤢𞥄𞤱𞤮, romanized: Gine-Bisaawo; Mandinka: ߖߌ߬ߣߍ߫ ߓߌߛߊߥߏ߫ Gine-Bisawo

- ^ Portuguese: República da Guiné-Bissau [ʁɛˈpuβlikɐ ðɐ ɣiˈnɛ βiˈsaw]

- ^ Autonomous sector.

Geography

editGuinea-Bissau is bordered by Senegal to the north and Guinea to the south and east,[75] with the Atlantic Ocean to its west.[75] It lies mostly between latitudes 11° and 13°N (a small area is south of 11°), and longitudes 11° and 15°W.[76]

At 36,125 square kilometres (13,948 sq mi),[75] the country is larger in size than Taiwan or Belgium. The highest point is Monte Torin with an elevation of 262 metres (860 ft). Its terrain is mostly low coastal plains with swamps of the Guinean mangroves rising to the Guinean forest–savanna mosaic in the east.[77] Its monsoon-like rainy season alternates with periods of hot, dry harmattan winds blowing from the Sahara. The Bijagos Archipelago lies off of the mainland.[78] The country is home to two ecoregions: Guinean forest–savanna mosaic and Guinean mangroves.[79]

Climate

editGuinea-Bissau is warm all year round with mild temperature fluctuations; it averages 26.3 °C (79.3 °F). The average rainfall for Bissau is 2,024 millimetres (79.7 in), although this is almost entirely accounted for during the rainy season which falls between June and September/October. From December through April, the country experiences drought.[80]

Economy

editGuinea-Bissau's GDP per capita and Human Development Index are among the lowest in the world. More than two-thirds of the population lives below the poverty line.[81] The economy depends mainly on agriculture; fish, cashew nuts, and ground nuts are its major exports.[82]

A long period of political instability has resulted in depressed economic activity, deteriorating social conditions, and increased macroeconomic imbalances. It takes longer on average to register a new business in Guinea-Bissau (233 days or about 33 weeks) than in any other country in the world except Suriname.[83]

Guinea-Bissau has started to show some economic advances after a pact of stability was signed by the main political parties of the country, leading to an IMF-backed structural reform program.[84]

After several years of economic downturn and political instability, in 1997, Guinea-Bissau entered the CFA franc monetary system, bringing about some internal monetary stability.[85] The civil war from 1998 to 1999, and a military coup in September 2003, again disrupted economic activity, leaving a substantial part of the economic and social infrastructure in ruins and intensifying the already widespread poverty. Following the parliamentary elections in March 2004 and presidential elections in July 2005, the country is trying to recover from the long period of instability, despite a still-fragile political situation.[86]

Beginning around 2005, drug traffickers based in Latin America began to use Guinea-Bissau, along with several neighbouring West African nations, as a transshipment point to Europe for cocaine.[87] The nation was described by a United Nations official as being at risk for becoming a "narco-state".[88] The government and the military have done little to stop drug trafficking, which increased after the 2012 coup d'état.[89] The government of Guinea-Bissau continues to be ravaged by illegal drug distribution, according to The Economist.[90] Guinea-Bissau is a member of the Organization for the Harmonisation of Business Law in Africa (OHADA).[91]

Society

editDemographics

editAccording to the 2022 revision of the World Population Prospects[93][94], Guinea-Bissau's population was 2,060,721 in 2021, compared to 518,000 in 1950. The proportion of the population below the age of 15 in 2010 was 41.3%, 55.4% were aged between 15 and 65 years of age, while 3.3% were aged 65 years or older.[92]

Ethnic groups

editThe population of Guinea-Bissau is ethnically diverse and has many distinct languages, customs, and social structures.[69]

Bissau-Guineans can be divided into the following ethnic groups:[69]

- Fula and the Mandinka-speaking people, who constitute the largest portion of the population and are concentrated in the north and northeast;[69]

- Balanta and Papel people, who live in the southern coastal regions;[69] and

- Manjaco and Mancanha, who occupy the central and northern coastal areas.[69]

Most of the remainder are mestiços of mixed Portuguese and African descent.[96][97]

Portuguese natives are a very small percentage of Bissau-Guineans.[96] After Guinea-Bissau gained independence, most of the Portuguese nationals left the country. The country has a tiny Chinese population.[98] These include traders and merchants of mixed Portuguese and Cantonese ancestry from the former Asian Portuguese colony of Macau.[96]

Major cities

editMain cities in Guinea-Bissau include:[99]

| Rank | City | Population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2015 estimate | Region | ||

| 1 | Bissau | 492,004 | Bissau |

| 2 | Gabú | 48,670 | Gabú |

| 3 | Bafatá | 37,985 | Bafatá |

| 4 | Bissorã | 29,468 | Oio |

| 5 | Bolama | 16,216 | Bolama |

| 6 | Cacheu | 14,320 | Cacheu |

| 7 | Bubaque | 12,922 | Bolama |

| 8 | Catió | 11,498 | Tombali |

| 9 | Mansôa | 9,198 | Oio |

| 10 | Buba | 8,993 | Quinara |

Languages

editThough a small country, Guinea-Bissau has several ethnic groups which are very distinct from each other, with their own cultures and languages. This is due to Guinea-Bissau being a refugee and migration territory within Africa. Colonisation and racial intermixing brought Portuguese and the Portuguese creole known as Kriol or crioulo.[100]

The sole official language of Guinea-Bissau since independence, Standard Portuguese is spoken mostly as a second language, with few native speakers and its use is often confined to the intellectual and political elites. It is the language of government and national communication as a legacy of colonial rule. Schooling from the primary to tertiary levels is conducted in Portuguese, although only 67% of children have access to any formal education. Data suggests that the number of Portuguese speakers ranges from 11 to 15%.[96] In the latest census (2009) 27.1% of the population claimed to speak non-creole Portuguese (46.3% of city dwellers and 14.7% of the rural population, respectively).[101] Portuguese creole is spoken by 44% of the population and is effectively the lingua franca among distinct groups for most of the population.[96] Creole's usage is still expanding, and it is understood by the vast majority of the population. However, decreolisation processes are occurring, due to undergoing interference from Standard Portuguese and the creole forms a continuum of varieties with the standard language, the most distant are basilects and the closer ones, acrolects. A post-creole continuum exists in Guinea-Bissau and crioulo 'leve' ('soft' creole) variety being closer to the Portuguese-language norm.[100]

The remaining rural population speaks a variety of native African languages unique to each ethnicity: Fula (16%), Balanta (14%), Mandinka (7%), Manjak (5%), Papel (3%), Felupe (1%), Beafada (0.7%), Bijagó (0.3%), and Nalu (0.1%), which form the ethnic African languages spoken by the population.[100][102] Most Portuguese and Mestiços speakers also have one of the African languages and Kriol as additional languages. Ethnic African languages are not discouraged, in any situation, despite their lower prestige. These languages are the link between individuals of the same ethnic background and daily used in villages, between neighbours or friends, traditional and religious ceremonies, and also used in contact between the urban and rural populations. However, none of these languages are dominant in Guinea-Bissau.[100]

French is taught as a foreign language in schools, because Guinea-Bissau is surrounded by French-speaking nations.[96] Guinea-Bissau is a full member of the Francophonie.[103]

Religion

editVarious studies suggest that slightly less than half of the population of Guinea-Bissau is Muslim, while substantial minorities follow folk religions or Christianity. The CIA World Factbook's 2020 estimate stated that the population was 46.1% Muslim, 30.6% following folk religions, 18.9% Christian, 4.4% other or unaffiliated.[1] In 2010, a Pew Research survey determined that the population was 45.1% Muslim and 19.7% Christian, with 30.9% practicing folk religion and 4.3 other faiths.[17][104] A 2015 Pew-Templeton study found that the population was 45.1% Muslim, 30.9% practicing folk religions, 19.7% Christian, and 4.3% unaffiliated.[105] The ARDA projected in 2020 the share of the Muslim population to be 44.7%. It also estimated 41.2% of the population to be practitioners of ethnic religions and 13% to be Christians.[106]

Concerning religious identity among Muslims, a Pew report determined that in Guinea-Bissau there is no prevailing sectarian identity. Guinea-Bissau shared this distinction with other Sub-Saharan countries like Tanzania, Uganda, Liberia, Nigeria and Cameroon. [107]This Pew research also stated that countries in this specific study that declared to not have any clear dominant sectarian identity were mostly concentrated in Sub-Saharan Africa.[107] Another Pew report, The Future of World Religions, predicts that from 2010 to 2050, practitioners of Islam will increase their share of the population in Guinea-Bissau.[105]

Many residents practice syncretic forms of Islamic and Christian faiths, combining their practices with traditional African beliefs.[77][108] Muslims dominate the north and east, while Christians dominate the south and coastal regions. The Roman Catholic Church claims most of the Christian community.[109]

The 2021 US Department of State Report on International Religious Freedom[110] mentions the fact that leaders of different religious communities believe that the existing communities are essentially tolerant, but express some concerns about rising religious fundamentalism in the country. An incident in July 2022, when a Catholic church in the overwhelmingly Muslim region of Gabú was vandalised, raised concern amongst the Christian community that Islamic extremism might be infiltrating the country. However, there have been no further similar incidents, and no direct links to Islamic extremists have surfaced.[111]

Education

editEducation is compulsory from the age of 7 to 13.[112] Pre-school education for children between three and six years of age is optional and in its early stages. There are five levels of education: pre-school, elemental and complementary basic education, general and complementary secondary education, general secondary education, technical and professional teaching, and higher education (university and non-universities). Basic education is under reform, and now forms a single cycle, comprising six years of education. Secondary education is widely available and there are two cycles (7th to 9th classe and 10th to 11th classe). Professional education in public institutions is nonoperational, however private school offerings opened, including the Centro de Formação São João Bosco (since 2004) and the Centro de Formação Luís Inácio Lula da Silva (since 2011).[100]

Higher education is limited and most prefer to be educated abroad, with students preferring to enroll in Portugal.[100] A number of universities, to which an institutionally autonomous Faculty of Law as well as a Faculty of Medicine that is maintained by Cuba and functions in different cities.

Child labor is very common.[113] The enrollment of boys is higher than that of girls. In 1998, the gross primary enrollment rate was 53.5%, with higher enrollment ratio for males (67.7%) compared to females (40%).[113]

Non-formal education is centered on community schools and the teaching of adults.[100] In 2011, the literacy rate was estimated at 55.3% (68.9% male, and 42.1% female).[114]

Conflicts

editUsually, the many different ethnic groups in Guinea-Bissau coexist peacefully, but when conflicts do erupt, they tend to revolve around access to land.[115]

Culture

editMedia

editMusic

editThe music of Guinea-Bissau is usually associated with the polyrhythmic gumbe genre, the country's primary musical export. However, civil unrest and other factors have combined over the years to keep gumbe, and other genres, out of mainstream audiences, even in generally syncretist African countries.[116]

The cabasa is the primary musical instrument of Guinea-Bissau,[117] and is used in extremely swift and rhythmically complex dance music. Lyrics are almost always in Guinea-Bissau Creole, a Portuguese-based creole language, and are often humorous and topical, revolving around current events and controversies.[118]

The word gumbe is sometimes used generically, to refer to any music of the country, although it most specifically refers to a unique style that fuses about ten of the country's folk music traditions.[119] Tina and tinga are other popular genres, while extent folk traditions include ceremonial music used in funerals, initiations, and other rituals, as well as Balanta brosca and kussundé, Mandinga djambadon, and the kundere sound of the Bissagos Islands.[120]

Cuisine

editCommon dishes include soups and stews. Common ingredients include yams, sweet potato, cassava, onion, tomato, and plantain. Spices, peppers, and chilis are used in cooking, including Aframomum melegueta seeds (Guinea pepper).[121]

Film

editFlora Gomes is an internationally renowned film director; his most famous film is Nha Fala (English: My Voice).[122] Gomes's Mortu Nega (Death Denied) (1988)[123] was the first fiction film and the second feature film ever made in Guinea-Bissau. (The first feature film was N'tturudu, by director Umban u'Kest in 1987.) At FESPACO 1989, Mortu Nega won the prestigious Oumarou Ganda Prize. In 1992, Gomes directed Udju Azul di Yonta,[124] which was screened in the Un Certain Regard section at the 1992 Cannes Film Festival.[125] Gomes has also served on the boards of many Africa-centric film festivals.[126] The actress Babetida Sadjo was born in Bafatá, Guinea-Bissau.[127]

Sports

editFootball is the most popular sport in Guinea-Bissau. The Guinea-Bissau national football team is under the authority of the Federação de Futebol da Guiné-Bissau. They are a member of the Confederation of African Football (CAF) and FIFA.[citation needed][128]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ a b c d "Guinea Bissau". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau". United States Department of State. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "Religions in Guinea Bissau | PEW-GRF". globalreligiousfutures.org. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau", The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 22 September 2022, retrieved 8 October 2022

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau" – Field Listing: Nationality. Archived 26 June 2015 at the Wayback Machine The World Factbook 2013–14. Washington, DC: Central Intelligence Agency, 2013. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau". The World Factbook (2025 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 22 June 2023. (Archived 2023 edition.)

- ^ a b c d "World Economic Outlook Database, October 2023 Edition (Guinea-Bissau)". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved 10 December 2023.

- ^ "Gini Index coefficient". The World Factbook. Retrieved 25 September 2024.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/2024" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. Archived (PDF) from the original on 13 March 2024. Retrieved 13 March 2024.

- ^ "Overview". The World Bank. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ a b c "Guinea-Bissau – Country Profile – Nations Online Project". nationsonline.org. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ a b Bowman, Joye L. (22 January 2009). "Abdul Njai: Ally and Enemy of the Portuguese in Guinea-Bissau, 1895–1919". The Journal of African History. 27 (3): 463–479. doi:10.1017/S0021853700023276. S2CID 162344466.

- ^ Corbin, Amy; Tindall, Ashley. "Bijagós Archipelago". Sacred Land Film Project. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau: Swearing-in of new President unlikely to bring stability, says UN representative". UN News. 14 February 2020. Retrieved 23 September 2020.

- ^ Handem, Myrna (2015). Portuguese, Creole, or Both: The Problematic of Language Choice in the Republic of Guinea-Bissau. The Social, Political and Economic Implications of Language Choice (Ph. D. thesis). Howard University.

- ^ "Africa: Guinea-Bissau". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. Archived from the original on 22 October 2020. Retrieved 1 January 2020.

- ^ a b "Chapter 1: Religious Affiliation". Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa (Report). Pew Research Center. 15 April 2010.

- ^ a b c "Early history". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 20 August 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u Rodney, Walter Anthony (May 1966). "A History of the Upper Guinea Coast, 1545–1800" (PDF). Eprints. Archived (PDF) from the original on 7 March 2020. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e Schoenmakers, Hans (1987). "Old Men and New State Structures in Guinea-Bissau". The Journal of Legal Pluralism and Unofficial Law. 19 (25–26): 99–138. doi:10.1080/07329113.1987.10756396.

- ^ Nanque, Neemias Antonio (2016). Revoltas e resistências dos Papéis da Guiné-Bissau contra o Colonialismo Português – 1886–1915 (PDF) (Trabalho de conclusão de curso). Universidade da Integração Internacional da Lusofonia Afro-Brasileira. Archived (PDF) from the original on 20 September 2022. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Lobban, Richard Andrew Jr.; Mendy, Peter Karibe (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Guinea-Bissau (4th ed.). Lanham: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-5310-2.

- ^ Mendy, Peter Karibe; Jr, Richard A. Lobban (2013). Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Guinea-Bissau. Scarecrow Press. p. 160. ISBN 978-0-8108-8027-6.

- ^ a b c Wright, Donald R (1987). "The Epic of Kalefa Saane as a guide to the Nature of Precolonial Senegambian Society-and Vice Versa". History in Africa. 14: 287–309. doi:10.2307/3171842. JSTOR 3171842. S2CID 162851641.

- ^ Page, Willie F. (2005). Davis, R. Hunt (ed.). Encyclopedia of African History and Culture. Vol. III (Illustrated, revised ed.). Facts On File. p. 92.

- ^ "Kaabu Oral History Project Proposal" (PDF). African Union Common Repository. 20 June 1980. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ^ Hair, P. E. H. (1994). "The Early Sources on Guinea" (PDF). History in Africa. 21: 87–126. doi:10.2307/3171882. JSTOR 3171882. S2CID 161811816 – via Cambridge University Press.

- ^ a b c "HISTORY OF GUINEA-BISSAU". historyworld.net. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "British Library – Endangered Archive Programme (EAP)". inep-bissau.org. 18 March 1921. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Gale Group. (2017). "Guinea-Bissau." In M. S. Hill (Ed.), Worldmark encyclopedia of the nations (14th ed., Vol. 2, pp. 379–392). Gale.

- ^ Brittain, Victoria (17 January 2011). "Africa: a continent drenched in the blood of revolutionary heroes". The Guardian. London. Archived from the original on 17 January 2017. Retrieved 14 December 2016.

- ^ Benzinho, Joana; Rosa, Marta (December 2015). Discovering Guinea-Bissau (PDF). NGO afectos com Letra. p. 29. ISBN 978-989-20-6315-7. Archived (PDF) from the original on 5 January 2017. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ Johnson, Thomas A. (11 September 1974). "Portugal Formally Grants Guinea-Bissau Freedom". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ^ Ratiu, Ion; Rațiu, Ion (1975). Ion Rațiu, Foreign Affairs Publishing Company, 1975, Contemporary Romania: Her Place in World Affairs, p. 90. Foreign Affairs Publishing Company. ISBN 9780900380167.

- ^ "RFE/RL, 1979. Radio Free Europe Research, Volume 4, Issues 15–27". April 1979.

- ^ Mourão, Daniele Ellery (April 2009). "Guiné-Bissau e Cabo Verde: identidades e nacionalidades em construção". Pro-Posições (in Portuguese). 20: 83–101. doi:10.1590/S0103-73072009000100006. ISSN 1980-6248.

- ^ Agency, Central Intelligence (2013). The World Factbook 2012-13. U.S. Executive Office of the President. p. 311. ISBN 978-0-16-091142-2.

- ^ Berg, Tiago José (26 November 2012). Hinos de todos os países do mundo. Panda Books. p. 178. ISBN 9788578881917.

- ^ Diario, Nós (16 December 2016). "Literatura para a militância nacional: hinos da lusofonia". Nós Diario (in Galician). Retrieved 24 January 2022.

- ^ "Tobias Engel, A sina da instabilidade, biblioteca diplo". Archived from the original on 3 March 2022. Retrieved 3 March 2022.

- ^ Uppsala Conflict Data Program Conflict Encyclopedia, Guinea Bissau: government, in depth, Negotiations, Veira's surrender and the end of the conflict Archived 31 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, viewed 12 July 2013,

- ^ Guinea-Bissau's Kumba Yala: from crisis to crisis Archived 16 July 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Afrol.com. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Smith, Brian (27 September 2003) "US and UN give tacit backing to Guinea Bissau coup" Archived 27 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine, Wsws.org, September 2003. Retrieved 22 June 2013

- ^ "Armed forces chief killed as soldiers mutiny over pay arrears". The New Humanitarian. 7 October 2004. Retrieved 28 October 2022.

- ^ GUINEA-BISSAU: Vieira officially declared president Archived 25 August 2012 at the Wayback Machine. irinnews.org (10 August 2005).

- ^ "Army man wins G Bissau election". London: BBC News. 28 July 2005. Archived from the original on 27 June 2006. Retrieved 5 January 2010.

- ^ Guinea Bissau vote goes smooth amid hopes for stability. AFP via Google.com (16 November 2008). Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Balde, Assimo (24 November 2008). "Coup attempt fails in Guinea-Bissau". London: The Independent UK. Archived from the original on 15 May 2011. Retrieved 28 June 2010.

- ^ "Soldiers kill fleeing President". Archived from the original on 8 March 2009. Retrieved 2 March 2009.. news.com.au (2 March 2009).

- ^ Elections, Guinea-Bissau (27 May 2009). "On the Radio Waves in Guinea-Bissau". swisspeace. Archived from the original on 8 December 2009. Retrieved 7 February 2010.

- ^ "Já foi escolhida a data para a realização das eleições presidenciais entecipadas". Bissaudigital.com. 1 April 2009. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 26 June 2010.

- ^ Dabo, Alberto (29 July 2009). "Sanha wins Guinea-Bissau presidential election". Reuters. Retrieved 17 December 2020.

- ^ "Tiny Guinea-Bissau becomes latest West African nation hit by coup". Bissau. 12 April 2012. Archived from the original on 13 April 2012. Retrieved 14 April 2012.

- ^ Embalo, Allen Yero (14 April 2012). "Fears grow for members of toppled G.Bissau government". Agence France-Presse. Archived from the original on 3 March 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau opposition vows to reach deal with junta | Radio Netherlands Worldwide". Rnw.nl. 15 April 2012. Archived from the original on 12 October 2014. Retrieved 2 May 2012.

- ^ a b Tasamba, James (29 November 2019). "Guinea-Bissau's leader concedes election defeat". Anadolu Agency. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau: Former PM Embalo wins presidential election". BBC news. 1 January 2020. Retrieved 14 June 2021.

- ^ "Fears of Guinea-Bissau coup attempt amid gunfire in capital". The Guardian. 1 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Heavy gunfire heard near presidential palace in Guinea-Bissau". Al Jazeera English. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ "Gunfire near government house in Guinea-Bissau". France 24. 1 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ Dabo, Alberto (2 February 2022). "Six killed in failed coup in Guinea-Bissau". Reuters. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau president says 'many' dead after 'failed attack against democracy'". France 24. 1 February 2022. Retrieved 1 February 2022.

- ^ a b Portugal, Rádio e Televisão de (7 February 2022). "Rádio Capital, na Guiné-Bissau, atacada por grupo de homens armados". Rádio Capital, na Guiné-Bissau, atacada por grupo de homens armados (in Portuguese). Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ a b "Guiné-Bissau vive 'clima de terror'". Jornal SOL (in Portuguese). 13 February 2022. Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Staff writer (26 October 2022). "Ukraine interested in building multifaceted relations with African countries – Zelenskyy after meeting with President of Guinea-Bissau". President of Ukraine Official Website. Retrieved 3 September 2023.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau president says this week's violence was 'attempted coup'". Al Jazeera. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau's president issues a decree dissolving the opposition-controlled parliament". AP News. 4 December 2023. Retrieved 20 February 2024.

- ^ ""Guinea-Bissau President Umaro Sissoco Embaló Declines Second Term Amid Political Uncertainty"". africanews.com/. 13 September 2024. Retrieved 13 September 2024.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Guinea-Bissau (09/03)". U.S. Department of State. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Guinea-Bissau Supreme Court Archived 23 January 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Stj.pt. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Guinea-Bissau Political Parties Archived 9 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Nationsencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ "CPLP – Comunidade dos Países de Língua Portuguesa – Histórico – Como surgiu?". CPLP. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Chapter XXVI: Disarmament – No. 9 Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons". United Nations Treaty Collection. 7 July 2017.

- ^ "Administrative Map of Guinea-Bissau 1200 pixel – Nations Online Project". nationsonline.org. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Guinea-Bissau Maps & Facts". WorldAtlas. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "Coordinates of Guinea-Bissau". GeoDatos. 2021. Retrieved 25 February 2021.

- ^ a b "Guinea-Bissau" Archived 28 December 2010 at the Wayback Machine, CIA the World Factbook, Cia.gov. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ Nossiter, Adam (4 November 2009) "Bijagós, a Tranquil Haven in a Troubled Land", The New York Times, 8 November 2009

- ^ Dinerstein, Eric; Olson, David; Joshi, Anup; Vynne, Carly; Burgess, Neil D.; Wikramanayake, Eric; Hahn, Nathan; Palminteri, Suzanne; Hedao, Prashant; Noss, Reed; Hansen, Matt; Locke, Harvey; Ellis, Erle C; Jones, Benjamin; Barber, Charles Victor; Hayes, Randy; Kormos, Cyril; Martin, Vance; Crist, Eileen; Sechrest, Wes; Price, Lori; Baillie, Jonathan E. M.; Weeden, Don; Suckling, Kierán; Davis, Crystal; Sizer, Nigel; Moore, Rebecca; Thau, David; Birch, Tanya; Potapov, Peter; Turubanova, Svetlana; Tyukavina, Alexandra; de Souza, Nadia; Pintea, Lilian; Brito, José C.; Llewellyn, Othman A.; Miller, Anthony G.; Patzelt, Annette; Ghazanfar, Shahina A.; Timberlake, Jonathan; Klöser, Heinz; Shennan-Farpón, Yara; Kindt, Roeland; Lillesø, Jens-Peter Barnekow; van Breugel, Paulo; Graudal, Lars; Voge, Maianna; Al-Shammari, Khalaf F.; Saleem, Muhammad (2017). "An Ecoregion-Based Approach to Protecting Half the Terrestrial Realm". BioScience. 67 (6): 534–545. doi:10.1093/biosci/bix014. ISSN 0006-3568. PMC 5451287. PMID 28608869.

- ^ Guinea-Bissau Climate Archived 9 May 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Nationsencyclopedia.com. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ World Bank profile Archived 11 November 2012 at the Wayback Machine. World Bank.org (31 May 2013). Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau country profile". BBC News. 2 March 2020. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ The Economist (2007). Pocket World in Figures. London: Profile Books. ISBN 978-1861978448.

- ^ Guinea-Bissau and the IMF Archived 16 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Imf.org (13 May 2013). Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ CFA Franc and Guinea-Bissau Archived 26 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Uemoa.int. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau". Encyclopædia Britannica. Encyclopædia Britannica, inc. 2020.

- ^ Guinea-Bissau:A narco-state? Archived 29 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Time. (29 October 2009). Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Sullivan, Kevin (25 May 2008). "Route of Evil: How a tiny West African nation became a key smuggling hub for Colombian cocaine, and the price it is paying". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 27 August 2017.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau drug trade 'rises since coup'". London: BBC News. 31 July 2012. Archived from the original on 27 October 2012. Retrieved 5 October 2012.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau, Africa's most famous narco-state, goes to the polls". The Economist. 2 November 2019. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019.

- ^ "The business law portal in Africa". OHADA.com (in French). Paul Bayzelon. Archived from the original on 26 March 2009. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Population Division of the Department of Economic and Social Affairs of the United Nations Secretariat, World Population Prospects: The 2010 Revision". Esa.un.org. Archived from the original on 6 May 2011. Retrieved 20 January 2017.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ a b "Recenseamento Geral da População e Habitação 2009 Características Socioculturais" (PDF). Instituto Nacional de Estatística Guiné-Bissau. p. 22. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 November 2015. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f "History & Geography – GUINEA BISSAU REPUBLIC". Archived from the original on 31 January 2021. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ Berlin, Ira (1 April 1996). "From Creole to African". William and Mary Quarterly. 53 (2): 266. doi:10.2307/2947401. JSTOR 2947401. Retrieved 6 June 2022.

- ^ China-Guinea-Bissau Archived 11 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. China.org.cn. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau: Regions, Cities & Urban Localities – Population Statistics in Maps and Charts". citypopulation.de. Archived from the original on 2 December 2017. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- ^ a b c d e f g Barbosa, José (2015). Língua e desenvolvimento: O caso da Guiné-Bissau [Language and Development: The case of Guinea-Bissau] (PDF) (Master's thesis) (in Portuguese). Universidade de Lisboa. Archived (PDF) from the original on 9 August 2017. Retrieved 10 May 2017.

- ^ Mendes, Etoal (2018). Experiências de ensino bilíngue em Bubaque, Guiné-Bissau: línguas e saberes locais na educação escolar [Bilingual teaching experiences in Bubaque, Guinea-Bissau: languages and local knowledge in school education] (PDF) (Master's thesis) (in Portuguese). Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul. hdl:10183/178453. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 December 2019.

- ^ "Crioulo, Upper Guinea". Ethnologue. Archived from the original on 14 April 2013. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ "Welcome to the International Organisation of La Francophonie's Official Website". Francophonie.org. Archived from the original on 1 April 2014. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Tolerance and Tension: Islam and Christianity in Sub-Saharan Africa (PDF) (Report). Pew Forum on Religious & Public life. April 2010. p. 20. Archived from the original (PDF) on 30 April 2018. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ a b "Religions in Guinea Bissau". Global Religious Futures. Pew-Templeton. Archived from the original on 29 January 2018. Retrieved 11 October 2019.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau: Major World Religions (1900–2050)". Association of Religion Data Archives. Retrieved 8 October 2022.

- ^ a b The World's Muslims: Unity and Diversity (PDF) (Report). Pew Research Center. 9 August 2012. p. 29. Archived from the original (PDF) on 24 October 2012.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau" Archived 16 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Encyclopædia Britannica

- ^ Guinea-Bissau: Society & Culture Complete Report an All-Inclusive Profile Combining All of Our Society and Culture Reports (2nd ed.). Petaluma: World Trade Press. 2010. p. 7. ISBN 978-1607804666.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau". United States Department of State. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ dimasaryo (8 July 2022). "Catholics in Guinea-Bissau unsettled by vandalism of a church". ACN International. Retrieved 1 November 2022.

- ^ "Guinea-Bissau Education System". scholaro.com. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ a b "Guinea-Bissau". 2001 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor. Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2002). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Field Listing :: Literacy". The World Factbook. Archived from the original on 24 November 2016. Retrieved 15 October 2014.

- ^ Armando Mussa Sani; Jasmina Barckhausen (23 June 2017). "Theatre sheds light on conflicts". D+C, development and cooperation. Archived from the original on 15 August 2017. Retrieved 15 August 2017.

- ^ Lobeck, Katharina (21 May 2003) Manecas Costa Paraiso di Gumbe Review Archived 24 February 2018 at the Wayback Machine. BBC. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ The Kora. Freewebs.com. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Radio Africa: Guinea Bissau vinyl discography Archived 25 October 2012 at the Wayback Machine. Radioafrica.com.au. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ "Radio Gumbe". Archived from the original on 28 September 2018.

- ^ Music of Guinea-Bissau Archived 5 June 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Ccas11bijagos.pbworks.com. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ "Eat locally in Guinea Bissau". Slow Food International. 25 July 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2022.

- ^ "Nha Fala/My Voice". spot.pcc.edu. 2002. Archived from the original on 8 February 2013.

- ^ Mortu Nega Archived 18 December 2008 at the Wayback Machine. California Newsreel. Newsreel.org. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ Udju Azul di Yonta Archived 5 July 2009 at the Wayback Machine. California Newsreel. Newsreel.org. Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ "Festival de Cannes: Udju Azul di Yonta". Festival de Cannes. Archived from the original on 20 October 2014. Retrieved 16 August 2009.

- ^ Flora Gomes The Two Faces of War: National Liberation in Guinea-Bissau Archived 8 February 2013 at the Wayback Machine. Watsoninstitute.org (25 October 2007). Retrieved 22 June 2013.

- ^ de Lamalle, Patrick (19 October 2018). "Babetida Sadjo, est-ce que vous l'avez vu ?". RTBF (in French). Archived from the original on 9 March 2021. Retrieved 12 January 2019.

- ^ "CAF qualifying draw made for FIFA World Cup 26™". FIFA. 2023. Retrieved 17 July 2024.

Sources

edit- Barry, Boubacar (1998). Senegambia and the Atlantic slave trade. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Clarence-Smith, W. G. (1975). The Third Portuguese Empire, 1825-1975. Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press.

- Hair, P.E.H. (22 January 2009). "Ethnolinguistic Continuity on the Guinea Coast" (PDF). The Journal of African History. 8 (2): 247–268. doi:10.1017/S0021853700007040. JSTOR 179482. S2CID 161528479.

- Niane, Djibril Tamsir (1989). Histoire des Mandingues de l'Ouest: le royaume du Gabou. Paris: Karthala. ISBN 9782865372362. Retrieved 2 August 2023.

- Ogilby, John (1670). Africa: being an accurate description of the regions of Aegypt, Barbary, Lybia, and Billedulgerid, the land of Negroes, Guinee, Aethiopia, and the Abyssines, with all the adjacent islands, either in the Mediterranean, Atlantick, Southern, or Oriental Sea, belonging thereunto: with the several denominations of their coasts, harbors, creeks, rivers, lakes, cities, towns, castles, and villages: their customs, modes, and manners, languages, religions, and inexhaustible treasure: with their governments and policy, variety of trade and barter, and also of their wonderful plants, beasts, birds, and serpents. London: Printed by Tho. Johnson for the author. Retrieved 25 November 2022 – via Early English Books.

- Attribution

This article incorporates public domain material from The World Factbook. CIA.

Further reading

edit- Abdel Malek, K.,"Le processus d'accès à l'indépendance de la Guinée-Bissau", Bulletin de l'Association des Anciens Elèves de l'Institut National de Langues et de Cultures Orientales, No. 1, April 1998. pp. 53–60

- Forrest, Joshua B., Lineages of State Fragility. Rural Civil Society in Guinea-Bissau (Ohio University Press/James Currey Ltd., 2003)

- Galli, Rosemary E, Guinea Bissau: Politics, Economics and Society, Pinter Pub Ltd., 1987

- Lobban, Richard Andrew Jr., and Mendy, Peter Karibe, Historical Dictionary of the Republic of Guinea-Bissau, third edition (Scarecrow Press, 1997)

- Vigh, Henrik, Navigating Terrains of War: Youth And Soldiering in Guinea-Bissau, Berghahn Books, 2006

External links

edit- Wikimedia Atlas of Guinea-Bissau

- Official website, Government of Guinea-Bissau

- Country Profile from BBC News

- Guinea-Bissau profile from ECOWAS

- Guinea-Bissau at the Encyclopædia Britannica

- News headline links from Al Jazeera.