Hagia Irene (Greek: Αγία Ειρήνη) or Hagia Eirene (Medieval Greek: Ἁγία Εἰρήνη Greek pronunciation: [aˈʝia iˈrini], "Holy Peace", Turkish: Aya İrini), sometimes known also as Saint Irene, is an Eastern Orthodox church located in the outer courtyard of Topkapı Palace in Istanbul. It is the oldest known church structure in the city and one of the only Byzantine churches in Istanbul that was never converted into a mosque, alongside the Church of Saint Mary of the Mongols, as it was used as an arsenal for storing weapons until the 19th century.[1] The Hagia Irene today[when?] operates as a museum and concert hall.

| Hagia Irene | |

|---|---|

| |

| Status | Museum |

| Location | |

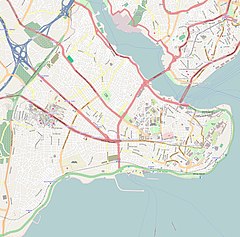

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°0′35″N 28°58′52″E / 41.00972°N 28.98111°E |

| Architecture | |

| Type | Church |

| Style | Byzantine |

| Groundbreaking | 532 |

| Materials | Brick, stone |

| Website | |

| Part of | Historic Areas of Istanbul |

| Criteria | Cultural: i, ii, iii, iv |

| Reference | 356 |

| Inscription | 1985 (9th Session) |

Naming

editThe church was dedicated to the peace of God, and is one of the three shrines which emperors devoted to God's attributes, together with Hagia Sophia (Wisdom) and Hagia Dynamis.[2]

Introduction

editOrigins

editThe building reputedly stands on the site of a pre-Christian temple. It ranks as the first church completed in Constantinople, before Hagia Sophia, during its transformation from a Greek trading colony to the eastern capital of the Roman Empire. According to later tradition but disputed by some scholars, the Roman emperor Constantine I commissioned the first Hagia Irene church in the 4th century, which was completed by the end of his reign (337). When Constantine died, it is believed that his resting place may be the porphyry sarcophagus that lay in the courtyard.[3] It served as the church of the Patriarchate before Hagia Sophia was completed in 360 under Constantius II.[4] During the Nika revolt in 532,[5] Hagia Irene was burned down. In the wake of the riots, Emperor Justinian I, who had almost been deposed during the riot, had the church rebuilt in 548 as part of a widespread architectural project. It was then damaged again by the 740 Constantinople earthquake on October 20, 740, about six months before the death of Leo III.[6] The Emperor Constantine V ordered the restorations[6] and had its interior decorated with mosaics and frescoes. Some restorations from this time have survived to the present.

Historical context

editThroughout the history of the Roman Empire, emperors were often away from the seat of power for extended periods of time. However, a trend was being established near the end of the Late-Antiquity period of Rome and into the early Byzantine period that saw emperors remaining at the capital. At the time of the Hagia Irene’s founding, Constantinople was not yet recognized as the capital and seat of power of the Byzantine Emperors due to the frequent travels of Emperor Constantine (r. 306-337), as it is understood that imperial power wasn’t necessarily concentrated in a capital like Rome, but around the emperor when he embarked on his travels. As Constantine’s dynasty unfolded, each emperor made more and more improvements to the city that would see the consolidation of the city’s status as a true seat of power. By Emperor Constantius II’s reign (r. 337-361), the city featured an impressive amount of public and political institutions: a Senate building, libraries, bathouses, and churches.[7]

There is very little scholarship on the function of the Hagia Irene from Constantine, even during the turbulent periods of theological controversies. One of the early challenges facing the developing Christian Church was the Arian controversy, which centered around Christ being divine or not. To resolve this issue, a council was held at Nicea that resulted in the widely accepted Nicean Creed, which stated that Christ was begotten from God, and as such is divine.

The arrival of Justinian to the throne in 527 saw a concerted effort to stamp out any deviation from Orthodoxy as defined by the Nicean council and all following councils, and these efforts were directed against Jews, pagans, and “heretics”. Jews were alienated from Byzantine society, and Jewish writings began shifting from Greek to Hebrew as they retreated to the safety of their own culture.[8] Pagans had restrictive laws placed against them, with severe penalties, including death, for breaking them. Any sort of coordinated resistance efforts were squashed. Samaritans, an ethno-religious group similar to Jews, rose up against the Byzantine Empire in 529 and were ruthlessly suppressed, with almost 100,000 being killed during the suppression of the uprising.[9]

Politically, the Church and the Western/Eastern Roman emperors interacted with each other with various power dynamics. On one hand, it was apparent that church leaders had, at times, significant power over the emperor, such as St. Ambrose denying Theodosius I entry to the church in Milan until he repented for his role in the Massacre of Thessalonica.[10] However, at other times there were interactions that were friendly. Liturgical practices during services at the Hagia Sophia during Justinian’s reign saw the emperor and the Patriarch of Constantinople, in a private room high above and away from the citizens of Constantinople, engage in prayer to God before returning to lead the congregation together.[11] Despite moments of difference between the state and the church throughout Byzantine history, Justinian’s aforementioned stance on religious deviation showed a common imperial and religious goal.

The Hagia Irene church witnessed one of the most devastating episodes in the history of Constantinople as a city, which was the Nika Revolt in 532. Around the time of Justinian’s campaign of religious consolidation,[12] A riot broke out after a chariot race at the Hippodrome that nearly saw the emperor deposed. The riot spread quickly, engulfing the entire city in violence, and a majority of the city would be razed during the events of the revolt.[13] The Hagia Irene was destroyed during the revolt, but it is unknown why it was targeted by the rioters (although it was the seat of the Patriarchate, which is significant considering the timing of the riot just several years after Justinian’s initiation of a widespread crackdown on religious dissent). The rebuilt Hagia Irene was constructed as part of Justinian’s massive architectural project that was happening across the empire, and the design of the church was based on the emerging “centrally-planned” design of churches that was becoming more and more standardized.[14] Additionally, the church had hospices added to it to service the poor and sick, and Justinian endowed it with regular funds to keep it running.[15] A similar endeavor happened earlier under Constantine, where he built several churches in the easternmost portions of his empire as part of a good-will project that not only included the building of architectural works, but charity to the poor as well.[16]

Arsenal

editAfter the Fall of Constantinople in 1453 by Mehmed II, the church was enclosed inside the walls of the Topkapi palace. The Janissaries used the church as an arsenal (Cebehane) until 1826.[17] It was also used as a warehouse for military equipment and repository for trophies of arms and military regalia taken by the Turks.[17] During the reign of Sultan Ahmet III (1703–1730) it was converted into the National Military Museum in 1726.[17]

In 1846, Marshal of the Imperial Arsenal, Ahmed Fethi Paşa, made the church a military antiques museum.[18] It was used as the Military Museum from 1908 until 1978 when it was then turned over to the Turkish Ministry of Culture.

Concert hall

editToday, the Hagia Irene serves mainly as a concert hall for classical music performances, due to its extraordinary acoustic characteristics and impressive atmosphere. Many of the concerts of the Istanbul International Music Festival have been held here every summer since 1980.

In 2000, the Turkish haute couture designer Faruk Saraç produced a special show here. A collection of 700 designed pieces inspired by the Ottoman sultans, including the robes of 36 sultans ranging from Osman Gazi, the founder of the Ottoman Empire to the last sultan, Mehmed VI, were on display. The show was accompanied by music and the story of the sultans' lives and demonstrations of Ottoman-era dancing.

For many years, the Hagia Irene was only accessible during events or by special permission, but the museum has been open to the public every day except Tuesday since January 2014.[19]

Structure

editChurch architecture

editReconstruction during the reign of Justinian I shows change in the architecture of the atrium and narthex, which stayed intact after the earthquake. Restoration after the earthquake created a stronger foundation for the church.[6] Before being rebuilt, the foundation had significant structural problems.[6] This restoration established a cross-domed plan on the gallery level while still being able to keep the original basilica plan at the ground level.[6] The narthex can be found to the west, preceded by the atrium, and then the apse on the east side.[6] Hagia Irene still has its dome and has peaked roofs on the north, west, and south sides of the church.[6] The dome itself is 15m wide and 35m high and has twenty windows. Hagia Irene has the typical form of a Roman basilica, consisting of a nave and two aisles, which are divided by three pairs of piers.[6] This helps support the galleries above the narthex.[6] Semicircular arches are also attached to the capitals which also helps give support to the galleries above.[6]

Art inside the church

editIn Byzantine tradition, there is a unique vestige of the Iconoclastic art within the church. The apse semidome and the bema arch are covered with mosaics.[6] There are also the frescoes which can be found on the south side aisle.[21] These mosaics date back to about the 8th century. This was during the time of the earthquake which most of the upper parts of the church can be dated back to.[22] There is also a mosaic of a cross, which is outlined in black with a gold ground.[6] The ends are flared along with having teardrop shapes at the end. This extends around the base of the semidome.[6] The cross was put in during the reconstruction by Constantine V, which was during the Iconoclastic years.[21] On the bema arch there is an inscription of Psalm 64 verses 4–5 on the inner side, and then on the outer side there is an inscription of Amos 6 verse 6. There is evidence of alterations on these inscriptions as well.[6] The inscriptions detail a praise to the church as it is the house of the lord.[21] The verses, especially the Psalm, were used as inspiration for some of the mosaics in Hagia Sophia.[21]

Hagia Irene also holds a synthronon. Synthronons are rows of built benches that are arranged in a semicircle in the apse. During Divine Liturgy this is where the clergy would sit.[21] This is the only synthronon that has survived in the city from the Byzantine era.[6] The synthronon in Hagia Irene has six tiers of seats. There are doors at both side that open up into an ambulatory beneath the fourth tier of seats.

The capitals of the original church building were removed during a reconstruction in the Byzantine era, and only ten of them were reused in the atrium of the building. They show monograms with the names and titles of the imperial couple Justinian and Theodora.[23]

Historiography

editScholarly debates surrounding ulterior uses of churches

editAlthough scholarly work on the Hagia Irene mainly centers on some of its architectural features, looking at the different scholarly interpretations of architecture, both religious and secular, in Byzantine society can provide a glimpse into the church and state dynamics of the time. There is debate among scholars as to the extent of the usage of churches as “imperial propaganda”, especially once Christianity is established as the state religion. Back during Rome’s status as a unified empire, architecture as manifestations of state power was used extensively, and can be seen primarily through triumphal arches, which were often placed at areas where Rome achieved great victories.[24] Information put forward by author Jelena Bogdanovic in her article “The Relational Spiritual Geopolitics of Constantinople, the Capital of the Byzantine Empire” may highlight some continuity with this tradition. Emperor Constantine had a porphyry statue of himself dressed as Helios, and this statue had what is believed to be fragments of the True Cross and the axe Noah used to build the Ark inserted into the column, which may signify the transition between the traditional pagan religions of Rome into Christianity as the eventual state religion.[25] Additionally, author Peter Sarris examines developments in the Byzantine Empire during the reign of Justinian and spends a significant amount of time in the article how Justinian wanted almost every aspect of the Byzantine State to reflect Christianity, and paraphrases historian Averil Cameron’s description of Justinian’s rebuilding of Constantinople as the unification of the political and religious ceremonial.[12]

Work from other scholars keep in line with the idea of continuity, but some of the content written indicates that the displaying of “personal” propaganda had to be toned down. In the book “The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian”, contributor Joseph Alchermes discusses how the patronage of grand churches like the Hagia Sophia may have been used in political infighting during the time of Justinian. Like the Hagia Irene, Emperor Justinian I rebuilt the Hagia Sophia after it was razed during the Nika Revolt. There was an apparent rivalry between Justinian and noblewoman Ancinia Juliana, who was a patron of the Hagia Polyeuktos church.[26] The Hagia Polyeuktos Church was one of the most opulent churches in the Byzantine Empire before the Hagia Sophia’s reconstruction, and it even boasted a commemorative plaque that featured text that could be construed as a challenge to Justinian. When Justinian entered the church for the first time, he boasted that he had surpassed Solomon, a reference to part of the text on the Polyeuktos' plaque.[26] Still, other scholars have chosen to focus on churches through their function as a place of worship. Author Allan Doig notes that the unique church architecture that occurred under Justinian such as the centrally planned church were made to improve the liturgical processes of churches by encouraging those who visited to gain an understanding of God by contemplating three things: the architecture of the church, the liturgical services, and the scriptures itself.[5]

Gallery

edit- Hagia Irene

-

Ground plan of the church

-

Hagia Irene with Hagia Sophia at the back

-

Church of St Irene roof from afar

-

Church of St Irene exterior from west

-

Church of St Irene exterior

-

Church of St Irene exterior

-

Church of St Irene exterior

-

Church of St Irene exterior

-

Church of St Irene interior

-

Church of St Irene apse

-

Church of St Irene interior

-

Church of St Irene narthex

-

Church of St Irene narthex

-

Church of St Irene atrium seen from narthex

-

Church of St Irene atrium

-

Church of St Irene interior

-

The apse of Hagia Irene without seats (April 2024)

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "History". Askeri Müze ve Kültür Sitesi Komutanlığı. Archived from the original on 23 November 2019. Retrieved 23 November 2019.

- ^ Janin, pg. 106

- ^ Kaldellis, Anthony (2024). The New Roman Empire. Oxford University PressNew York. doi:10.1093/oso/9780197549322.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-19-754932-2.

- ^ Charles Matson Odahl, Constantine and the Christian Empire, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 2010), 237–39.

- ^ a b Allan Doig, Liturgy and Architecture: From the Early Church to the Middle Ages, (Ashgate Publishing, 2008), 65.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Freely, John; Cakmak, Ahmet (2004). Byzantine Monuments of Istanbul. Cambridge University Press. pp. 136–143. ISBN 978-0521772570.

- ^ Destephen, Sylvain (2019). From Mobile Center to Constantinople. Washington D.C: Dumbarton Oaks. pp. 1–4.

- ^ Evans, J.A.S (1996). The Age of Justinian: Circumstances of Imperial Power. New York: Routledge. pp. 246–248.

- ^ Evans. Age of Justinian. p. 248.

- ^ Allan Doig, Liturgy and Architecture from the Early Church to the Middle Ages (Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2008), 61.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Doig, Liturgy and Architecture, 74-76.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Peter Sarris, Economy Society In The Age of Justinian (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 206.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Evans, Age of Justinian, 248.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Doig, Liturgy and Architecture, 74-76.

{{cite book}}: Missing or empty|title=(help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ Stewart, Aubrey (1888). Buildings of Justinian. London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Kaldellis, Anthony (2023). The New Roman Empire: A History of Byzantium. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 118.

- ^ a b c Pyhrr, Stuart (1989). "European Armor from the Imperial Ottoman Arsenal". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 24: 85–116. doi:10.2307/1512872. JSTOR 1512872. S2CID 191412421.

- ^ Museums and Narratives of Display from the late Ottoman Empire to the Turkish Republic, Wendy Shaw, Muqarnas, Vol.XXIV, (Brill, 2007), 256.

- ^ "Hagia Irene Museum Opened". Topkapi Palace Museum. 6 January 2014. Archived from the original on 2 October 2017. Retrieved 10 October 2014.

- ^ Stroth, Fabian (2021). Monogrammkapitelle. Die justinianische Bauskulptur Konstantinopels als Textträger (in German). Wiesbaden: Reichert. p. 62. ISBN 978-3-95490-272-9.

- ^ a b c d e "Great Online Encyclopaedia of Constantinople". constantinople.ehw.gr. Retrieved 2017-03-14.

- ^ Kazhdan, Alexander P. (1991). Irene, Church of Saint – Oxford Reference. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001. ISBN 9780195046526.

- ^ Stroth, Fabian (2021). Monogrammkapitelle. Die justinianische Bauskulptur Konstantinopels als Textträger (in German). Wiesbaden: Reichert. pp. 55–63. ISBN 978-3-95490-272-9.

- ^ Haussler, Ralph (1999). "Architecture, Performance and Ritual: The Role of State Architecture in the Roman Empire". Theoretical Roman Archaeology Journal: 3–4.

- ^ Bogdanović, Jelena (2016), Bogdanović, Jelena; Christie, Jessica Joyce; Guzmán, Eulogio (eds.), "The Relational Spiritual Geopolitics of Constantinople, the Capital of the Byzantine Empire", Political Landscapes of Capital Cities, University Press of Colorado, pp. 97–154, ISBN 978-1-60732-468-3, JSTOR j.ctt1dfnt2b.9, retrieved 2023-12-13

- ^ a b Maas, Michael (2005). The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. Cambridge University Press. pp. 362–365.

Bibliography

edit- Akşit, I. (2005). Hagia Sophia: Akşit Kültür ve Turizm Yayincilik. Akşit Kültür ve Turizm Yayıncılık. ISBN 978-975-7039-07-5.

- Bogdanovic, Jelena. “The Relational Spiritual Geopolitics of Constantinople, the Capital of the Byzantine Empire”. In from Political Landscapes of Capital Cities, edited by Jelena Bogdanovic, Jessica Joyce Christie, and Eulogio Guzman (Boulder: University Press of Colorado, 2018), 106.

- Bogdanovic Jelena, "Hagia Eirene", 2008, Encyclopedia of the Hellenic World, Constantinople

- Davis, Fanny (1970). Palace of Topkapi in Istanbul. New York, Scribner. ASIN B000NP64Z2.

- Destephen, Sylvain, “From Mobile Center to Constantinople”, Dumbarton Oaks Papers (2019) 1-4.

- Doig, Allan. Liturgy and Architecture from the Early Church to the Middle Ages. Aldershot: Ashgate Publishing, 2008

- Evans, J.A.S. The Age of Justinian: Circumstances of Imperial Power. New York: Routledge, 1996

- Freely, John; Cakmak, Ahmet (2004). Byzantine Monuments of Istanbul. Cambridge University Press. pp. 136–143. ISBN 0521772575

- Haussler, Ralph. “Architecture, Performance and Ritual: The Role of State Architecture in the Roman Empire” Theoretical Roman Archaeology Journal (1999): 3-4.

- "Irene, Church of Saint – Oxford Reference". doi:10.1093/acref/9780195046526.001.0001/acref-9780195046526-e-2506.

- Janin, Raymond (1953). "Le Siège de Constantinople et le Patriarcat Oecuménique". La Géographie Ecclésiastique de l'Empire Byzantin (in French). 3rd Vol.: Les Églises et les Monastères (part 1). Paris: Institut Français d'Etudes Byzantines.

- Kaldellis, Anthony. The New Roman Empire: A History of Byzantium. New York: Oxford University Press, 2023.

- Kazhdan, Alexander, ed. (1991). Church of Saint s.v.Irene. Vol. 2nd of 3 vols. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0195046526.

{{cite book}}:|journal=ignored (help) - Krautheimer, Richard (1984). Early Christian and Byzantine Architecture. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-05294-7.

- Maas, Michael. The Cambridge Companion to the Age of Justinian. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Millingen, Alexander Van, Ramsey Traquair, Walter S. George, and Arthur e. Henderson. Byzantine churches in Constantinople: their history and architecture. London: Macmillan and Co., Limited, 1912. Print.

- Musilek, Josef, Lubos Podolka, and Monika Karkova, "The Unique Construction of the Church of Hagia Irene in Istanbul for The Teaching of Byzantine Architecture." Priced Engineering, 161 (2016): 1745–750. Web.

- Necipoğlu, Gülru (1991). Architecture, ceremonial, and power: The Topkapi Palace in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-14050-8.

- Peschlow, Urs (1977). Die Irenenkirche in Istanbul. Untersuchungen zur Architektur. Tübingen: Wasmuth.

- Procopius, Buildings of Justinian. Translated by Aubrey Stewart. London: n.p, 1888.

- Pyhrr, Stuart (1989). "European Armor from the Imperial Ottoman Arsenal". Metropolitan Museum Journal. 24: 85–116 JSTOR 1512872

- Sarris, Peter, Economy Society In The Age of Justinian. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006.

- Socrates SCHOLASTICUS. Historia Ecclesiastica. Translated by A.C Zenos. Buffalo, New York: Christian Literature Publishing Co., 1890.