Haugh or The Haugh is a small village or hamlet in East Ayrshire, Parish of Mauchline, Scotland. The habitation is situated about two and a half miles downstream from Catrine, on the north bank of the River Ayr. The River Ayr Way runs through the village.

Haugh

| |

|---|---|

Haugh Farm and the old mill | |

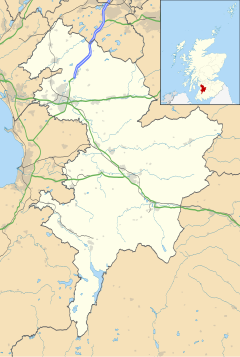

Location within East Ayrshire | |

| OS grid reference | NS 49790 25318 |

| Council area | |

| Lieutenancy area | |

| Country | Scotland |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Police | Scotland |

| Fire | Scottish |

| Ambulance | Scottish |

History

editHaugh is an Old English and Scots term referring to a low-lying meadow in a river valley, a most apt description of the geography of the site of Haugh village. The Cistercian monks had a corn mill at the Haugh in 1527.[1] A bridge was built to replace the earlier ford and the 19th century pedestrian suspension bridge,[2] however this vehicular bridge was badly damaged by a flood in August 1966 and was replaced in July 1967.[3] The old pedestrian suspension bridge that crossed the River Ayr at the Haugholm is now located near the Dean Park in Kilmarnock, straddling the Kilmarnock Water.[2]

Robert McCrone was a property owner here. One of his sons, Guy McCrone, was the author of many books, including the "Wax Fruit" trilogy which detailed the case of the disastrous 1878 collapse of the City of Glasgow Bank.[4]

One mile of the Haugh and Syke Road from Haugh Farm to the railway bridge was taken off the list of public highways in 1924. There was a ford over the River Ayr at Damhead (now demolished) that can still be seen.[5]

Mr Stewart of Haughhead gave three thousand pounds in the 1850s to establish the New Educational Institute of Mauchline, providing free education for fifty poor children of the parish.[6]

The author William Howie Wylie in 1851 describes the village in the following terms - "A rustic bridge spans the Ayr, whence a view of the cluster of houses may be obtained. The clachan is hemmed in on each hand by flowery knolls, wreathed with honeysuckle and wild roses. The cottages are neat and substantial, and are graced by pretty flower pots. The inhabitants derive support from the wool, corn, and saw-mills which the place contains".[7]

The lands of Over and Nether Haugh became known as Kinzeancleuche or Kingencleugh.[8]

Robert Burns

editLocal tradition maintains that Robert Burns used to visit the glen to enjoy a dip in the Kingen Cleugh Burn when he lived at Mossgiel Farm near Mauchline. The remains of an old stone built bath or cistern still exists with moss covered steps running down to it. Locals would point out this cistern as being a favourite bathing place where he enjoyed a dip in the refreshingly cool waters; a vague memory of a Lady Sophia is also associated with this site.[9] The site would have been ideal, sitting at the bottom of the glen with its rivulet and water also entering via the tunnel that runs down from above the Damhead Weir.

Cartographic evidence

editBlaeu's map of 1654 records a 'Heuch' at the site of the present day village.[10] In 1747 an unnamed settlement is indicated on Roy's map with Damhead named further up river, showing that a dam existed at this point at that date, some years before the days of Robert Burns.[11] In 1775 Haugh is shown on Armstrong's map.[12] Thomson's map of 1832 shows Haughmills with three mills indicated and the dwelling of Damhead is also shown up river.[13]

Industry

editOne of the special features of the village was the considerable effort that went into securing a plentiful supply of water for its water powered industries, including two tunnels cut through the soft red sandstone, the longest being at least 1000 feet or around 300 metres in length. The date of construction is unclear, however the 1747 dam could only have functioned if the tunnels were in place.

The village had at least four mills, including a corn and saw mill, a woollen and lint mills, also a curling stone mill and in one of the mills snuff boxes were manufactured. The corn and saw mill buildings still stand on the course of the old lade, next to Haugh Farm (2012).

The 25 in. OS maps show a stone bath or cistern at the bottom of the Kingen Cleugh Glen where all the burn's waters and those of the Damhead Weir lade and tunnel (at least 300 metres long from NS 4992 2530 to NS 5005 2533) were diverted and collected, leaving via a short tunnel cut through the rock and then running down to the Haugh village along an open lade.

In 1837 a woollen mill, as well as the previously noted combined corn and saw mill, were present, all drawing water from the aforementioned cistern and lade, about a quarter of a mile upstream. As stated, the lade was tunnelled through the soft red sandstone of the river gorge, and the tunnel mouths can still be seen, as can two stone arched footbridges over the lade, and an overflow sluice. No traces of the woollen mill, which in 1837 employed thirty persons spinning yarn for a Kilmarnock carpet factory,[14] have survived. This mill was the first in sequence to receive the lade waters.[15]

The 19th century[when?] OS map shows that a smithy was located opposite Haugh Farm and a malt kiln lay to the west of it. In 1846 a mill was based in the village that sharpened reaping hooks.[16]

The Curling Stone mill

editThe curling stone mill, T. and A. Kay's first factory, stood to the left of the lane to the Ballochmyle Creamery and had a loop on its lade that allowed water to be diverted away from it when so desired. Ailsa Craig granite was used 'from about 1780'.[17] Andrew Kay began producing stones at the Haugh in the 1860s. The business stayed in this small factory for over 40 years before moving to Barskimming Road in Mauchline in 1911. The company, now known as Kays of Scotland, is still in existence, supplying curling stones to places as diverse as Bulgaria, Israel and Japan.[18]

The Ballochmyle Creamery

editA lint mill used to occupy this site, subsequently purchased circa 1890 for use as a creamery and margarine factory. Pioneering work in the development of margarine was carried out here, especially a type that was suited to puff pastry production. The blue tilework bands on the building gave the name of the 'Blue Band' margarine type according to local tradition. Jurgens, later part of Unilever, purchased the factory in the mid-1920s and margarine production continued until after WWII.[19]

The old Ballochmyle Creamery factory complex sits at the end of a short lane at the point at which the long lade from Damhead Weir finally enters the River Ayr. It was built around 1900 in an unusual Swiss-style. The building is now unused (datum 2013) after a period of time when it was the site of an optical works that finally closed around 1987.[4]

- Views at the Haugh

-

The lade tunnel exit from Robert Burns' Bath in the Kingen Cleugh Glen.

-

The steps down to Robert Burns' Bath in the Kingen Cleugh Glen.

-

Robert Burns' Bath - the old cistern in the Kingen Cleugh Glen.

-

The Haugholm at the Haugh.

-

The old ford near Damhead over the River Ayr.

-

The site of the weirs near Damhead Cottage (now demolished).

-

The site of the old Haugholm Ford from the road bridge.

Micro-history

editThe Ballochmyle railway viaduct is close by and was clearly visible before the trees in the Ayr Gorge grew to block the view.[2]

The 1841 Census of Mauchline records James Dunsmore (35) and Agnes Goudie (30) as living in Haugh, with their children George (15), Isabella (12), Allan (10), James (8), Elizabeth (4) and Thomas (7 mos). Next door were living Duncan Dunsmore (38) and his wife Mary (40), and their children Allan (16), Alexander (12) and Mary (4). James and Duncan were both wool spinners.[20]

Howford Bridge below the site of old Catrine House was originally Haughford Bridge. The 1896 OS map shows over thirty buildings located in the village of Haugh.

In 1785 Paterson records that it was decided to "...rebuke before the congregation" James and Margaret Miller of Haughead who had entertained several people during the church service with meat and drink.[21]

The famous Ballochmyle cup and ring marks are located nearby on the Kingencleugh estate.

References

edit- Notes

- ^ The River Ayr Way Retrieved : 2012-06-23

- ^ a b c Ayrshire History Retrieved : 2012-06-23

- ^ Ayrshire History Retrieved : 2012-06-23

- ^ a b Love (2003), Page 151

- ^ Old Roads of Scotland Retrieved : 2012-06-24

- ^ Wylie, Page 74

- ^ Wylie, Page 77

- ^ Paterson, Page 566

- ^ Cuthbertson, Page 100

- ^ Blaeu's Map Retrieved : 2012-06-24

- ^ Roy's Map Retrieved : 2012-06-24

- ^ Armstrong's map Retrieved : 2012-06-24

- ^ Thomson's map Retrieved : 2012-06-24

- ^ Paterson, Page 538

- ^ Mills of the River Ayr Retrieved : 2012-06-18

- ^ Ayrshire Roots Retrieved : 2012-06-24

- ^ Scotland's Places Retrieved : 2012-06-24

- ^ Ayr Writers' Club Retrieved : 2012-06-24

- ^ British Listed Buildings Retrieved : 2012-06-24

- ^ Rootsweb Retrieved : 2012-06-24

- ^ Paterson,Page 549

- Sources

- Cuthbertson, D. C. Autumn in Kyle and the Charm of Cunninghame. London : Herbert Jenkins.

- Love, Dane (2003). Ayrshire : Discovering a County. Ayr : Fort Publishing. ISBN 0-9544461-1-9.

- Paterson, James (1863–66). History of the Counties of Ayr and Wigton. II - Kyle . Edinburgh : J. Stillie.

- Wylie, William (1851). Ayrshire Streams. London : Arthur Hall, Virtue, & Co.