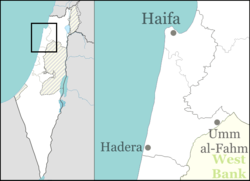

Jisr az-Zarqa (Arabic: جِسْر الزَّرْقَاء lit. The blue bridge, Hebrew: גִ'סְר א-זַּרְקָא; often shortened as Jisr) is an Israeli Arab town on Israel's northern Mediterranean coastal plain. Located just north of Caesarea within the Haifa District, it achieved local council status in 1963. According to the Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS) the town had a population of 13,689 in 2014,[3] living on 1,500 dunams (1.5 km2) of coastal land.[4] 80% of residents reportedly live below the poverty line.[5] The name Jisr az-Zarqa is a reference to Taninim Stream, which is known in Arabic as the "Blue Wadi" (Wadi az-Zarka). The mayor is Morad Ammash.

Jisr az-Zarqa

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

View of Jisr az-Zarqa | |

| Coordinates: 32°32′17″N 34°54′44″E / 32.53806°N 34.91222°E | |

| Grid position | 141/217 PAL |

| Country | Israel |

| District | |

| Government | |

| • Head of Municipality | Morad Ammash |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,520 dunams (1.52 km2 or 380 acres) |

| Population (2022)[1] | |

• Total | 15,502 |

| • Density | 10,000/km2 (26,000/sq mi) |

| Name meaning | The blue bridge (literally; understood to refer to the bridge over the River Zarka[2]) |

Jisr az-Zarqa is the only Arab-majority town in Israel located on the coast of the Mediterranean Sea.[6]

History

editExcavations have revealed walls with pottery remains dating from the 1st CE, with amphoras dating from the 4th to 7th CE,[7] and remains of a structure carrying a ceramic pipe, most probably dating to the Byzantine era.[8] It has been suggested that the aqueduct in Jisr az-Zarqa is part of the aqueduct ending in Caesarea Maritima, but was never completed.[9]

Ottoman era

editThe Jurban family was the first family coming from Jordan Valley, escaping due to conflict. Other main families are Amash from Qadum in West Bank, Najar from Al Arish or Egypt, Shihab from the Hauran, Twatcha and Um Bashi from Sudan.[10]

In 1882, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) described it: "This is properly speaking a dam rather than a bridge, built across the river so as to form a large pool. There is a causeway on the top of the dam: the height on the west is 20 feet; on the east the level of the water was 3 feet below the roadway. The masonry resembles that of the aqueduct fed from the pool. [..] The eastern face of the dam is cemented. Sluices lined with cement are constructed in the dam. The roadway is 8 feet to 10 feet broad. The work appears to be Roman."[11]

The SWP further noted: "There are small encampments of Arabs who live permanently in the marshes of the river Zerka. They are so strongly posted (the intricate way through the marshes being only known to themselves), that they are almost free from contributions to Government. They are known as 'Arab el Ghawarni."[12]

A population list from about 1887 showed that Guwarnet ez Zerka had about 335 inhabitants, all Muslim.[13]

British Mandate era

editIn the 1922 census of Palestine conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Jisr al Zarqa showed a population of 348 Muslims,[14] increasing in the 1931 census (when it was counted with Kabara) to 572 Muslims, in a total of 117 houses.[15]

In the 1945 statistics the population of Arab el Ghawarina (Jisr Zerqa) was 620, all Muslims,[16] while the total land area was 3,428 dunams, according to an official land and population survey.[17] Of this, 6 were plantations and irrigable land, 674 for grain crops,[18] while 69 dunams were classified as built-up (urban) areas.[19]

Israeli period

editBefore the establishment of the state, it was inhabited by Bedouin of the Ghawarina tribe.[20] The intervention of Jews from the neighboring towns of Zikhron Ya'akov and Binyamina, who relied on the population of Jisr az-Zarqa for agricultural labor, prevented the dispersal of its population in 1948.[21]

In November 2002, the Caesarea Development Corporation constructed a large earthen embankment running the length of the 160 meter-wide corridor between Jisr az-Zarqa and neighboring Caesarea. The embankment was built to block noise from the muezzin in local mosques, celebratory gunfire,[22] and to reduce property crime in surrounding communities.[23] Residents of Jisr az-Zarqa claim that the national park in the north, the embankment to the south, the highway to the east and the sea to the west, are keeping the town from expanding.[23][dead link]

The main coastal highway was built without providing an access to the village. However, a new interchange to Jisr az-Zarqa is being planned.[when?] The municipality of Jisr az-Zarka is seeking to promote environmental tourism to the town and its beachfront.[24] The Israel National Trail, a cross-country trail that runs from Dan in the north to Eilat in the south, passes through Jisr az-Zarka.[25] In 2013 it was reported that there were efforts to turn the town into a tourist destination[25][26]

In 2011, a women's leadership program was established in the wake of a similar project in the nearby town of Fureidis, to encourage women's participation in political and public leadership positions.[27]

Problems of pollution and overfishing in the coastal waters have affected the local economy, and many now work inland. From 20 to 30 buses transport on a daily basis Jisr az-Zarqa residents to jobs, mostly menial, in Haifa, Tel Aviv and elsewhere.[28]

Demographics

editThe inhabitants of Jisr az-Zarqa are primarily Muslim.[29]

The people of Jisr az-Zarqa belong to the Ghawarna,[30] i.e. people of the Ghor, a plain situated at the lowest end of a drainage system.[31] They come from various places.[30] According to one account, they were believed to be Sudanese people brought to work as slaves for the Bedouins.[30]

In 2020, the Mossawa Center, which advocates for Arab-Israeli rights, stated that 80% of residents live below the poverty line. Unemployment is high, and those who hold down a job on average earn half the national average in terms of income. Additionally, the average income in the village is only about half that of the national average.[32] In 2006 it had the highest school dropout rate in the country, at 12%.[33][34] By 2020, less than a quarter (23%) of high school students went on to graduate.[32]

A local resident, Mariam Amash, applied for a new identity card in Hadera in February 2008, using a birth document issued by the Ottoman Empire showing she was born in 1888. If verified by the Guinness Book of World Records, this would have made her the oldest living person in the world at 120.[35][36] She died on December 22, 2012, at the age of 124.[37]

In 1998, the first multiple kidney transplant in Israel took place between a couple from Jisr az-Zarqa and a Jewish couple from Jerusalem.[38]

Culture

editThe film Al Jiser (2004) by Ibtisam Mara'ana examines the lives of residents of Jisr-az Zarka.[39]

People from Jisr az-Zarqa

edit- Taleb Tawatha

- Mark Gerban -> First rower in history to represent the State of Palestine at the World Championships. He had the highest placed World Championship finish (16th) of a Palestinian athlete in any sport. Father is from Jisr az-Zarqa.

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "Regional Statistics". Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. Retrieved 21 March 2024.

- ^ Palmer, 1881, p. 140

- ^ "לוח 3.- אוכלוסייה( 1), ביישובים שמנו מעל 2,000 תושבים( 2) ושאר אוכלוסייה כפרית Population (1) of localities numbering above 2,000 Residents (2) and other rural population". Archived from the original on 3 October 2015. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ A Classic Zionist Story, Meron Rapoport, Jun 10, 2010, Haaretz

- ^ "In poor Arab villages like Jisr az-Zarka, poverty and alienation keep people from the polls". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- ^ "Overlooked Arab Israeli beach town opens its doors to tourists". The Times of Israel. Retrieved 2016-09-24.

- ^ Said, 2009, Jisr ez-Zarqa Final Report

- ^ Massarwa, 2010, Jisr ez-Zarqa, Final Report

- ^ Shadman, 2011, Jisr ez-Zarqa, Final Report

- ^ Bar Cohen, Anat (2001). The Relation between the Environment Conditions and the Traditional Rural Settlement and the Agrarian Situation in Menashe Plateau before 1948. Ramat Gan, Israel: Bar Ilan University (Thesis for Master Degree). p. 74.

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 13

- ^ Conder and Kitchener, 1882, SWP II, p. 35

- ^ Schumacher, 1888, p. 181

- ^ Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Haifa, p. 35

- ^ Mills, 1932, p. 92

- ^ Department of Statistics, 1945, p. 13

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 47 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 89

- ^ Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 139

- ^ Tyler, Warwick P. N. (October 7, 2001). State Lands and Rural Development in Mandatory Palestine, 1920-1948. Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 9781902210759. Retrieved October 7, 2019 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Sacred Landscape: CHAPTER FIVE". Archived from the original on 2006-09-04. Retrieved 2006-10-02.

- ^ "Caesarea". Archived from the original on October 8, 2006. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ a b "Website Disabled". friendvill1203.homestead.com. Archived from the original on January 3, 2006. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ Picow, Maurice (22 January 2011). ""Forgotten" Arab Israeli Town Gets Chance to Change Eco-Image". Green Prophet | Impact News for the Middle East. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ a b "Israel's Last Undiscovered Beach: Jisr Az Zarqa". Tablet Magazine. October 15, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ "Juha's guesthouse in Jisr a Zarqa. please enter the link below". Archived from the original on 2021-12-19. Retrieved October 7, 2019 – via www.youtube.com.

- ^ "In an Impoverished Israeli Arab Town, Women Are Learning the ABCs of Leadership". Haaretz. October 4, 2013. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ Skylar Lindsay, 'Palestinian fishermen struggle to survive next door to Netanyahu’s palatial suburb,' Mondoweiss 23 September 2016.

- ^ "Oops, Something is wrong" (PDF). www.cbs.gov.il. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

- ^ a b c Grossman, David (2004). Arab Demography and Early Jewish Settlement in Palestine: Distribution and Population Density during the Late Ottoman and Early Mandate Periods (in Hebrew). Jerusalem: The Hebrew University Magness Press, Jerusalem. p. 159. ISBN 978-965-493-184-7.

- ^ Khawalde, Sliman; Rabinowitz, Dan (2002). "Race from the Bottom of the Tribe That Never Was: Segmentary Narratives Amongst the Ghawarna of Galilee". Journal of Anthropological Research. 58 (2): 225–243. ISSN 0091-7710.

- ^ a b Naim Mousa and Wasim Nasser, 'Escorted by heavily armed police, Israel demolishes livelihood of local fisherman in Jisr al-Zarqa,' Mondoweiss 22 July 2020

- ^ "Jisr al-Zarqa, J'lem, Eilat have highest high school dropout rates". Haaretz. 8 September 2006.

- ^ "Equal opportunity? Not in our school". Haaretz. 27 September 2006.

- ^ Patience, Martin (2008-02-15). "World's 'oldest' person in Israel". BBC News. BBC MMVII. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ^ Goldstein, Tani (2008-02-12). "120 year-old woman files for identity card". Ynetnews. Ynetnews.com. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ^ "Mariam Amash, possibly world's oldest person, dies age 124 (with video)". Ynetnews.com. 2012-12-23. Archived from the original on 2012-12-23. Retrieved 2008-02-12.

- ^ "An Israeli and an Arab showing the way". ArabicNews.com. 13 May 1998. Archived from the original on 15 February 2006.

- ^ "Al-Jisr - Ibtisam Films". October 15, 2012. Archived from the original on October 15, 2012. Retrieved October 7, 2019.

Bibliography

edit- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Benveniśtî, M. (2000). Sacred landscape: the buried history of the Holy Land since 1948 (Illustrated ed.). University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21154-5.

- Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1882). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. Vol. 2. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945. Government of Palestine.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center. Archived from the original on 2018-12-08. Retrieved 2015-04-27.

- Massarwa, Abdallah (2010-10-03). "Jisr ez-Zarqa Final Report". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (122).

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (1994). "8". 1948 and after; Israel and the Palestinians. Oxford University Press. pp. Ghosh and Beit Naqquba, Al Fureidis. ISBN 0-19-827929-9.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Sa‘id, Kareem (2009-02-22). "Jisr ez-Zarqa Final Report". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (121). Archived from the original on 2011-07-19. Retrieved 2009-04-01.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly Statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

- Shadman, Amit (2011-06-25). "Jisr ez-Zarqa Final Report". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (123).

- Torgë, Hagit (2006-07-09). "Tel Tanninim". Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel (118).

External links

edit- Welcome To Kh. Jisr al-Zarqa, Palestine Remembered

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 7: IAA, Wikimedia commons