The Kizil Caves (also romanized as Qizil or Qyzyl; Uyghur: قىزىل مىڭ ئۆي, lit. 'The Thousand Red Houses'; Chinese: 克孜尔千佛洞; lit. 'Kizil Caves of the Thousand Buddhas') are a set of Buddhist rock-cut caves located near Kizil Township (克孜尔乡; Kèzī'ěr Xiāng) in Baicheng County, Aksu Prefecture, Xinjiang, China. The site is located on the northern bank of the Muzat River 65 kilometres (75 km by road) west of Kucha.[1][2] This area was a commercial hub of the Silk Road.[3] The caves have an important role in Central Asian art and in the Silk Road transmission of Buddhism, and are said to be the earliest major Buddhist cave complex in China, with development occurring between the 3rd and 8th centuries CE.[3] The caves of Kizil are the earlier of their type in China, and their model was later adopted in the construction of Buddhist caves further east.[4] Another name for the site has been Ming-oi (明屋), although this term is now mainly used for the site of Shorchuk to the east.[5]

Kizil Caves on the edge of the Tarim Basin. The Western Group of caves (caves 1–80) is seen at the forefront in perspective, while the Eastern Group (caves 136–201) appears far right in the background. The modern structures at the center approximately correspond to Caves 1 to 30. | |

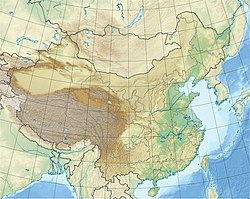

| Location | Xinjiang, China |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°47′04″N 82°30′17″E / 41.78444°N 82.50472°E |

| Kizil Caves | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Uyghur name | |||||||||

| Uyghur | قىزىل مىڭ ئۆي | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 克孜尔千佛洞 | ||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 克孜爾千佛洞 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Kizil Caves were inscribed in 2014 on the UNESCO World Heritage List as part of the Silk Roads: the Routes Network of Chang'an-Tianshan Corridor World Heritage Site.[6]

Caves

editThe Kizil Caves complex is the largest of the ancient Buddhist cave sites that are associated with the ancient Tocharian kingdom of Kucha, as well as the largest in Xinjiang. Other famous sites nearby are the Kizilgaha caves, the Kumtura Caves, Subashi Temple and the Simsim caves.[9][10] The Kizil Caves are "the earliest representative grottoes in China".[11] At the time the caves were created, the area of Kucha was following the orthodox Sarvastivadin school of Hinayana Buddhism, although an early and minority Dharmagupta presence has also been noted.[12] The simpler square caves may have been established by the Dharmagupta from the 4th century CE or earlier, while the "central pillar" caves, which flourished from the mid-6th century CE, can rather be associated with the Sarvastivadin school.[12]

Overview

editThere are 236 cave temples in Kizil, carved into the cliff stretching from east to west for a length of 2 km.[1] Of these, 135 are still relatively intact.[13] The earliest caves are dated, based in part on radioactive carbon dating, to around the year 300.[14] Most researchers believe that the caves were probably abandoned sometime around the beginning of the 8th century, after Tang influence reached the area.[15] Documents written in Tocharian languages were found in Kizil and a few of the caves contain Tocharian and Sanskrit inscriptions which give the names of a few rulers.

Many of the caves have a central pillar design, whereby pilgrims may circumambulate around a central column incorporating a niche for a statue of the Buddha, which is a representation of the stupa.

There are three other types of caves: square caves, caves "with a colossal image", and monastic cells (kuti). Around two-thirds of the caves are kutis which are monks' living quarters and store-houses and these caves do not contain mural paintings.[10] Chronology remains the subject of debate.[16][10]

"Central pillar" cave structure

editIn the typical "central pillar" design, pilgrims can circumambulate around a central column incorporating a niche for a statue of the Buddha, which is a representation of the stupa. The so-called "central pillar" which appears on a plan is actually not a pillar at all but only the rock at the back of the cave, into which was bored a circular corridor allowing for circumambulation.[17]

A large vaulted chamber is located in front of the "central pillar" column and a smaller rear chamber behind with two tunnel-like corridors on the sides linking these spaces. In the front chamber, a three-dimensional image of Buddha would have been housed in a large niche serving as the focus of the interior, however, none of these sculptures have survived at Kizil.[18] The rear chamber may feature the parinirvana scene in the form of a mural or large sculpture, and in some cases, a combination of both. The "central pillar" layout is possibly related to the structural design of Kara Tepe in northern Bactria.[19]

The program of the paintings in the "central pillar" caves generally follows a fixed arrangement: the walls of the main cella show sermons of the Buddha, the ceiling has rhomboid vignettes alluding to Jatakas, the central niche has the scene of the Indrasala Cave. The back room or corridor has scenes related to the Parinirvana, and finally the painting over the exit is related to the Tusita Heaven and the future Buddha Maitreya.[20]

Exploration

editThe Kizil Caves were first discovered and explored in 1902–1904 by the Ōtani expedition, a Japanese expedition under Tesshin Watanabe (渡辺哲信) and Kenyu Hori (堀賢雄), funded by Count Otani, but the expedition left hurriedly after four months of exploration in the area of Kucha, following a local earthquake.[25][26]

The Kizil caves were then explored by Albert Grünwedel, head of the Third German Turfan Expedition (December 1905 – July 6, 1907).[27] Albert von Le Coq was also part of the third German expedition and was under the direction of Albert Grünwedel, but only remained until June 1906, when he had to leave for British India due to a heavy illness.[28] The caves were photographed, drawings were made, and large portions of the murals were removed and sent to Germany.[29][28]

Grünwedel removed a great number of paintings, but was careful to make records before doing so in order to retain their archaeological value, and to photograph or draw them before cutting them out, out of fear that they could be destroyed upon removal or during transport.[30] He used a canvas to take quite precise records of the paintings. For example, Grünwedel recounts how he discovered a very interesting mural with warriors in the Cave of the Painters (207). Intending to remove it, he first made a precise drawing. But once the drawing was made, the mural disintegrated upon removal and was lost, except for a few fragments still in-situ.[31] Altogether, the Third German Expedition still removed many paintings, and shipped almost 120 crates of murals to Berlin.[32] Grünwedel published the result of his explorations in 1912 in Altbuddhistische Kultstätten in Chinesisch Turkistan, Bericht über archäologische Arbeiten von 1906 bis 1907 bei Kuča, Qarašahr und in der Oase Turfan.[28]

Grünwedel discovered that the Kizil Caves were essential in the understanding of the development of Buddhist art, and suggested some forms of Western artistic influences as well:

For years I have been endeavouring to find a credible thesis for the development of Buddhist art, and primarily to trace the ancient route by which the art of imperial Rome, etc..., reached the Far East. What I have seen here goes beyond my wildest dreams. If only I had hands enough to copy it all, [for] here in Kizil are about 300 caves, some of them containing frescoes, all of them very old and fine."

— Letter by Grünwedel, April 2, 1906.[33]

The French explorer Paul Pelliot and his photographer Charles Nouette, who were in Kucha from January 1907, visited Kizil soon after the German mission, from September 1, 1907, over a few days, and Charles Nouette took many beautiful and informative photographs.[34][35][36]

Albert von Le Coq came back to Kizil and surrounding areas in 1913–1914, heading the Fourth German Expedition, removing many paintings, including those Grünwedel had left in place, but generally taking much fewer records than his predecessor.[32][37]

Datation schemes

editAlbert Grünwedel and the German school

edit| Datation scheme according to the German school[38][39] | |||

| Style I "Gandharan" |

Style II "Sasanian" | ||

| 500–600 CE: Caves 207, 118, 76, 117, 77, 212, 83, 84 |

|||

In 1912 Grünwedel proposed in 1912 a structural scheme which remained influential throughout the 20th century. It is essentially based on the definition of two schools of art, "Style 1" and "Style 2".[38] Style I, qualified as "Indo-Iranian", derives from the Art of Gandhara, and murals tend to have dark cinnabar backgrounds with green and orange color schemes and natural shading, and the architecture tends to consist in squarish caves with cupola ceilings.[38][39] Style II derives from Sasanian art, and is characterized by a strong contrast between brilliant green-blue pigments.[38] Architecturally, the caves of Style II have a central stupa-pillar surrounded by a circular corridor for circumambulation. According to Grünwedel, Style II was before the 8th century CE. After Grünwedel, Albert von Le Coq and Ernst Waldschmidt proposed dates, based in the epigraphic inscriptions found in the caves. They proposed to date Style I from 500 to 600, and Style II from 600 to 650 CE. These chronological guidelines remained extremely influential throughout the 20th century, as late as the 1980s.[38]

Modern attempts at Carbon 14 dating

editVarious attempts at radio-carbon analysis were made over the years, with various degrees of success, but with the main effect of pushing back the dates of the first caves to circa 300 BCE, and challenging the German classification according to styles and colors schemes.[38]

In 1979, a Chinese institute (文物保护科学技术研究所, Wenwu baohu kexue jishu yanjiusuo) carbon-tested caves 63, 47, 13.[40]

Su Bai

edit| Datation scheme according to Su Bai (1981)[39][38] | |||

| Stage I "Initial stage" 310 CE +-80 350 CE +-60 |

Stage II "Flourishing stage" 395 CE +-65 465 CE +-65 |

Stage III "Decline stage" 545 CE +-75 685 CE +-65 | |

| Caves 38, 47, 6, 80, 13 | Caves 77, 17, 171, 104, 139, 119, 35, 36, 92, 118, 39, 49, 14 | Caves 201, 70, 148, 234, 187, 185, 182, 183, 181, 189, 190, 172, 8, 107B, 107A, 180, 197 | |

| Huo and Wang (1993)[38][39] | |||

| Stage I 200–350 CE |

Stage II 350–500 CE |

Stage III 500–700 CE | |

| Caves 118, 92, 77, 47, 48, 117, 161, 196, 224, 17, 104 | Caves 38, 76, 83, 84, 114, 13, 32, 171, 172 | Caves 110, 57, 212, 81, 184, 188, 199, 207, 8, 205, 99, 4, 123, 206, 178 | |

In 1979–1981, Su Bai (宿白) of Beijing University (北京大学历史系考古教研室, Beijing daxue lishi xi kaogu jiaoyanshi) made an influential carbon-testing campaign for caves 47, 3, 38, 6, 171, 17, 190, 8.[40] Based on these dates and on an analysis of the architecture of the caves (from the simpler to the more sophisticated), Su Bai proposed an influential dating scheme, pushing back the dates of the first caves to circa 300 CE.[39]

Huo and Wang

editIn 1989–1993, Huo and Wang (中国社会科学院考古研究所, Zhongguo shehui kexueyuan kaogu yanjiusuo) tested the following caves: 224, 76, 4, 8, 34, 68, 77, 98, 104, 114, 117, 118, 119, 125, 129, 135, 162, 171, 180, 189, 196, 198, 206, 212, 219, 227, 27, 39, 48, 60, 69, 84, 91, 92, 99, 123, 139, 161, 165, 178, 207.[40] They proposed a chronology which has some significant differences with the chronology previously proposed by Su Bai.[39]

Japanese teams of Nagoya University (日本名古屋大学) tested in 1995, 1997, 1998 and 2011 the following caves: 8, 171, 224, 13, 67, 76, 77, 92, 205.[40]

Many of the results remain inconclusive, sometimes even contradictory, and the historical period in question is rather too short in relation to the uncertainty margin of Carbon 14 datation, to provide a meaningful segmentation of the caves.[41] Most narrow Carbon dates given for the Kizil Caves refer to a 68% probability level (1σ), which implies a significant level of uncertainty, and when dates are adjusted to the 95% probability level (2σ) as standard archaeological practice requires,[42] then the timespan between the earliest and lowest dates becomes so large (about 200 to 300 years),[43] as to make individual comparisons between the caves meaningless.[44] Most researchers now use an approach combining artistic and architectural analysis together with carbon-dating, as a way to approach a reliable nomenclature, as proposed by Marylin Martin Rhie from 2001.[39]

Caves, murals and architecture

editIn 1906, the German expedition team of Albert Grünwedel explored the Kizil Caves. Albert von Le Coq, who worked under the direction Grünwedel, had to leave in June 1906 due to health problems.[28] Grünwedel generally photographed and copied the murals, before removing those he considered essential.[28] Most of the fragments removed are now in Museum of Asian Art (formerly Museum für Indische Kunst) in Dahlem, Berlin.[45] Other explorers removed some fragments of murals, that may now be found in museums in Russia, Japan, Korea and United States. Although the site has been both damaged and looted, around 5000 square metres of wall paintings remain,[46] These murals mostly depict Jataka stories, avadanas, and legends of the Buddha, and are an artistic representation in the tradition of the Hinayana school of the Sarvastivadas.[1]

Carbon-testing and stylistical analysis helped determine three main periods in the paintings at Kizil, which cover a period from 300 CE to 650 CE.[47] The early art of Kizil correspond to the Western school of art in the Tarim Basin, and mainly displays influences from Gandhara and the Iranian world, particularly influence from the Hephthalites, and no influence from East Asia.[48][49][50][51]

The Kizil Caves were designated by the Germans by a series of names, and have been separately numbered by the Chinese. A correspondence chart has been produced by Rhie.[52]

Some very early caves, now numbered 90–17 to 90–24, have been discovered since the 1990s in the lower parts of the cliff at the entrance of the central valley. These caves were square or rectangular with barrel-vaulted ceilings, but without any decorations.[53]

General characteristics

editA notable feature of the murals in Kizil is the extensive use of blue pigments, including the precious ultramarine pigment derived from lapis lazuli from Afghanistan. In the classification of the art of the region by Ernst Waldschmidt, there are three distinct periods:[1] the murals from the first phase are characterized by the use of reddish pigments, while those from the second phase used bluish pigments in abundance.[15] The earlier paintings reflect more Greco-Indian or Gandharan influences, while the second ones show Iranian (Sassanian) influences.[14] Later caves seem to have fewer legends and/or jatakas, being replaced by the repetitive designs of numerous small Buddhas (the so-called thousand Buddha motif), or sitting Buddhas with nimbuses.[1] The paintings of the first two phases showed a lack of Chinese elements.[15] The last phase, the Turkic-Chinese period, is most in evidence in the Turfan area, but in Kizil only two caves showed Tang Chinese influence.

Another characteristic of the Kizil murals is the division into diamond-shaped blocks in the vault ceilings of the main room of many caves. Buddhist scenes are depicted inside these diamond-shapes in many layers on top of one another to show the narrative sequences of the scenes.[1]

Color pigments

editThe pigments in the painting of the Kizil Caves have been analysed by X-ray diffraction analysis. The reds are primarily vermilion and red lead, which today are greatly discolored, and red ocher. Blue pigments are from lapis lazuli. Green pigments are from copper hydroxy chloride minerals such as atacamite. Brownish-black pigments are PbO2, obtained from the oxidation of red lead. White pigments were mainly obtained from gypsum.[11]

Style periods

editA broad classification of styles, formalized by Le Coq and Waldschmidt in 1933,[54] has been generally accepted.[55]

The first style is called "Indo-Iranian style I", and cover all the early caves with delicate tone-on-tone paintings, using browns, oranges and greens. The name "Indo-Iranian" broadly denotes the artistic influence from India, combined with elements of Iranian art, that presided over the creation of the first cave paintings at Kizil.[54] The main representative caves of this style are the Cave of the Hippocampi (Cave 118), the Cave of the Painters (Cave 207), the Peacock Cave (Cave 76), the Overpainted Cave (Cave 117), the Cave of the Statues (Cave 77), and the Cave of the Seafarers (Cave 112). The small group of the Treasure Cave (Cave 83, 84) is considered as contemporary, but in a slightly personal style, sometimes called "Special Style" (Sonderstil).[54] The first style is only found in Kizil, except for one cave in nearby Kumtura: the Cave with the cupola.[54]

The second style is called "Indo-Iranian style II", and cover most of the other caves of Kizil, which use strongly contrasted colors and strong line strokes, using browns, oranges and greens and especially a vivid lapis-lazuli blue. The name "Indo-Iranian" again broadly denotes the artistic influence from India, combined with important influences from Central Asian and the Iranian world.[54] This style is further divided in three broad periods.[54]

Finally, a third Uighur-Chinese style appears in only two caves at Kizil.

First Indo-Iranian Style: delicate "orange and green" paintings

editSe pañäkte saṅketavattse ṣarsa papaiykau

"This Buddha by Sanketava's hand was painted".[56][57][58][59]

Often attributed in the past to the 7th century CE,[56] but now carbon dated to 245–340 CE.[60]

The Kingdom of Kucha, the most populous oasis in the Tarim Basin, occupied a strategic position on the Northern Silk Road, which brought it prosperity, and made it a wealthy center of trade and culture.[61] Kucha was part of the Silk Road economy, and was in contact with the rest of Central Asia, including Sogdiana and Bactria, and thus also with the cultures of India, Iran, and coastal areas of China.[62] Early visitors are known, such Maes Titianus.[63] Since the 2nd century CE, under the auspices of the Han dynasty and the Kushan Empire, numerous great Buddhist missionaries passed through the Tarim Basin on their way to China, such as the Parthian An Shigao, the Yuezhis Lokaksema and Zhi Qian, or the Indian Chu Sho-fu (竺朔佛).[64] Culture flourished, and Indian Sanskrit scriptures were being translated by the Kuchean monk and translator Kumarajiva (344–413 CE), himself the son of a Buddhist man from Kashmir and a Kuchean princess, sister of the King.[64][61]

The 1st Style, sometimes called "First Indo-Iranian style" to denote influences from India and Central Asia, covers a period from 300 to 500 CE, and is characterized by Gandharan themes and orange and green hues, having a strong flavour of India: female dancers and musicians are often naked or half-naked with full breasts.[65][66] The art of these paintings is quite refined, and forms the "Classical" period of the art of Kizil: the shades are delicate, the lines are fine and elegant, the colors blend progressively to give a sense of texture and volume.[67] The paintings of Bamiyan in northern Afghanistan are generally considered as the precussors of the art of the Kizil Caves.[68] Towards the end of the period, the influence of the art of Gandhara is considered as a consequence of the political unification of the area between Bactria and Kucha under the Hephthalites, which lasted from 480 to 560 CE, or a few decades later.[69]

Period 1: "Classical" early style (circa 300–400 CE)

editThe earliest paintings at Kizil belong to a "Classical" stage. Their style is very elegant and "painterly", with sophisticated shading of the bodies to express sculptural volume. The lines are refined and subtle, the colors blend softly.[70] This style is also characteristically Indian, and may be related to Gandhara or Kashmir.[70] This early style is exemplified by the Cave of the Hippocampi (Cave 118), and may form a distinctive school. This contrasts with the style of the following stage, as seen in the panels in the cella of the Cave of the Statues, such as the "Cowherd Nanda", which is much bolder, using intense colors (but still browns, greens and oranges only), thicker lines and simpler patterns.[70]

Early paintings

editEarly inscriptions in Tocharian, an Indo-European language using a derivation of the Indian Brahmi script is used in several early paintings on tablets, as found in the Cave above the cave of the coffered ceiling (Cave 171),[56] or the Cave of the Niche (Cave 27).[71]

-

Kizil First Period 300-395 CE

-

Kizil First Period 300-395 CE (devotee detail)

-

Kizil First Period 300-395 CE. Tocharian inscription: "The Buddha was painted by the hand of Ratna(...)".[72]

Earliest painted caves

edit(cave 118, 300–350 CE)

According to the Chinese chronicles of the Jin dynasty (265-316 CE), there were already a thousand Buddhist stupas and temples in Kucha by the 3rd century CE.[76][77]

The earliest painted caves at Kizil are thought to be Cave of the Hippocampi (Cave 118) and Treasure Caves C and B (Caves 83 and 84 respectively).[73] Cave 118, possibly the earliest of the three, is located deep inside the central valley.[78] Cave 83 and 84 are located at the entrance of the same valley. These caves have simple architectural structures, together with paintings in a clear style, reflecting Indian influences.[73] Noble or wealthy Tocharian donors from Kucha, wearing tunics, sometimes appear kneeling at the side of devotional paintings.[75]

"Cave of the Hippocampi" (Cave 118, 300–350 CE)

editThe Cave of the Hippocampi (Cave 118) was visited and photographed by the Third German Expedition of 1906–1907, and by the French expedition of Paul Pelliot in 1907.[27] Large portions of the murals were removed and sent to Germany, especially by von Le Coq in 1914, who removed the lunettes and the sides of the vault.[29]

The cave consists of a rectangular room (3.6 x 4.8 meters), the entrance being on the long side, and the ceiling of which forms a transverse barrel vault.[73] In front of the cave, which is accessible through a door, there used to be an equally wide open space, perhaps adorned with paintings, with remains of a pyramid roof.[73] The two rooms are separated by a 1-meter-thick wall.[29] The model for this kind of vaulted cave can be found in Bactria at Kara Tepe, dating from the 2nd-3rd century CE.[73]

In the middle of the back wall of the main cella stands a large painting (3.42 m wide and 2.16 m high), with an unidentified scene of a King with attendants, possibly "The skill and music in the heavenly palace" (天宫伎乐).[73] The attitudes and postures of the figures remind the reliefs of 3rd–4th century CE Nagarjunakonda.[73] A king is seated at the center, with numerous attendants surrounding him, especially a near-naked woman seated to his left.[29] They wear heavy round earrings with a central rosette design.[29] The modeling of the faces reminds of the statuary of Hadda in Gandhara.[29] The picture is elaborately framed by five successive decorative borders with naturalistic vine rinceau, suggestive of Roman art.[73]

The colors of the murals are various shades of brown, with smatterings of light green, but no blue, defining the so-called "orange and green" style.[73] The center of the ceiling has motifs of the sun and moon, two monks, and a bird flying with a human figure in its claws.[73] The sides of the ceiling are composed of diamond-shaped mountains, around which are naturalistic motifs of humans, animals, lakes and trees, a possibly Near-Eastern design which was generally adopted in later caves at Kizil.[73] A band of fantastic animals separated the ceiling from the side walls.[73] The general style appears to be early, and possibly derived from Kashmir and Cave 24 at Bamiyan.[73]

The lunettes bordering the ceiling display ornate Buddhist scenes.[29] The right lunette is difficult to identify, but seems to represent a king or a Bodhisattava bending towards a warrior figure.[29] The bottom portion shows a palatial scene, with a figure on a couch surrounded by devatas.[29] The left lunette shows the Buddha of the future Maitreya in the Tusita Heaven.[29] Below this is a depiction of Mount Sumeru surrounding by various Nagas, figures of devotees, and animals.[29]

Small figures of kneeling devotees in tunics, about 40 centimeters tall, some armed with a dagger, appear next to the left and right corners of the back-wall mural: probably noble and wealthy Kuchean donors of the 4th century CE.[75] One of the donors holds three burning incense cones. He is dressed in a bordered and turned-up, collarless tunic with close-fitting sleeves.[75] The tunic, which reaches slightly above the knee, is belted. The pants are of the same color and have the same border.[75] He wears gray calf boots with cruciate ligaments that run under the sole.[75] The figure behind holds a wreath and a kind of censer, is dressed in a black belted lap jacket with tight-fitting sleeves, which is provided with a red border all around, and an ample green dress.[75] Their hair is cut straight to the nuque, a hair style also referenced for the people of Kucha in the contemporary Chinese chronicles Jin Shu.[75][79] A kneeling monk appeared next to the top left corner of the main mural, in a red robe and with ocher shorn hair, engaged in shaping a ceremonial jar with a hammer, while behind him appeared a painter wearing a tunic similar to those of the donors on the other side, but whose head only remained.[80]

-

A reconstitution of the mural of the back wall

-

Cave of the Hippocampi, ceiling detail

-

Right portion of the cave, as photographed by Charles Nouette in 1907

"Treasure Cave C" (Cave 83, 300–350 CE)

edit(300–350 CE)

Cave 83 (Treasure Cave C) is part of the compact group of the four "Treasure Caves" (82, 83, 84, 85) located at the entrance of the central valley. It is a relatively small square cave (3.6x3.6m), with a podium in the middle, probably for a statue or a stupa.[73] Here the ceiling has collapsed, but probably formed a cupola.[73][81]

The back wall had a well-preserved scene of a Jataka story, the Rudrayana Legend from the Divyavadana, with king Rudrayana observing the dance of his Queen Chandraprabha, who appears nude except for thin veils and jewelry. During the dance, the king had a premonition that his wife would soon die, and she asked to become a Buddhist nun.[82][83][73] The style and attitudes of the figures are generally Indian, such as the Tribhanga posture of the dancer, of the way the King is seated. The flutering ribbons of the diadem worn by the king however, were adopted from Iranian royal symbolism.[81]

In this cave, the frames of the paintings, especially the vine rinceaux, are probably derived from Roman art of the 1st century CE.[73] This cave may be slightly earlier then Cave 84.[73] The mural was sent to Berlin by Grünwedel (Ref: MIK III 8443).[73]

These paintings are soft and delicate: volumes are defined by gradations of shades and colors, not by the sharp limit of a line. Overall, "the brush has the priority over drawing".[81]

-

Treasure Cave C with mural visible on the back wall, as of 1912.

-

Treasure Cave 83, attendants, with ornate capital in the background (detail)

"Treasure Cave B" (Cave 84, 300–350 CE)

editCave 84 (Treasure Cave B) was a square, probably domed cave (4x4m, here too the ceiling has collapsed), examplifying an earlier, simpler cave structure at Kizil, which is also known from Bamiyan (Cave 24).[73] The origin of the paintings in caves 84 seems Indian, probably from Kashmir.[73] They show groups of people standing around figures of the Buddha, who is either seated or standing.[73] The depth of placement is rather shallow, the figures are graceful with curved torsos. The faces are round and plump.[73] Rhies suggest a date of the first half of the 4th century for Cave 84.[73] All the paintings were sent to Berlin by Grünwedel.[73]

These two caves are adjoined to cave 82, an undecorated vihara also dated to 300–350 CE,[73] and cave 85, a small ruined cave.[73]

-

Treasure Cave B (Cave 84), with murals visible on the back wall as of 1912.

-

Known structure and decorative layout of Treasure Cave B (Cave 84)

-

People around the Buddha, Cave 84

-

Attendant, Cave 84

"Peacock Cave" (Cave 76, circa 400 CE)

editcirca 400 CE

The "Peacock Cave" (Pfauenhöhle in German)[88] is also an early cave, although dated slightly later to circa 400 CE, and next located "Cave of the statues" (Cave 77), in the second rocky outcrop just outside of the central valley.[89] It has been carbon dated to mid 4th-end 5th century CE.[90] It is said to be "the most recognizably Indian in the whole Kizil cycle".[91] The paintings echo the Art of Gandhara and the murals of Ajanta Caves.[91]

A rectangular vestibule, the vaulted roof of which is now collapsed, preceded the main chamber.[84] The main chamber has a domed ceiling, an innovation first seen in early caves at Bamiyan, and in caves 83 and 84 at Kizil.[84][92] Numerous statuettes of the Buddha, as well as decorated wooden benches and low display tables were discovered in the antechamber of the cave.[93]

In the center of the main chamber, there is a large podium, on which probably stood some major statuary associated with the Buddha.[84] The architecture of the cave displays a marked advancement compared to earlier caves, but is anterior to the "central pillar" cave structure.[84][92] Several paintings illustrate the life of the Buddha. Only the left wall of the main cella had remained in great part intact by the time Grünwedel visited. The top part of the wall showed four important moments of the life of the Buddha, while celestial observers stand on a balcony above: 1) the Birth of Siddharta and the first Three Steps in which the Buddha appears naked and already tall, 2) the Four Encounters outside of the palace, 3) the Seduction of Mara's daughters, who are turned into old women, and 4) the Assault of Mara.[84][94][95] The middle row was almost entirely damaged, although scenes of the Preaching Buddha were identifiable.[96] The panels can be numbered 5 to 9, but 5 and 9 being half-panels going over the adjacent walls.[96] In one of the panels appear soldiers similar to those of the Cave of the Painters.[96] The bottom of the wall contained fragments of panels showing: 10) the Parinirvana, 11) devotees looking at the Buddha being put in a coffin, 11) The Buddha in his coffin, and 12) would have been the Cremation of the Buddha.[96][84][95] The upper part of the mural was removed by Grünwedel, and sent to Germany in panels, where some are still held in the Museum für Indische Kunst.[84]

This presentation of the various events of the life of the Buddha in successive panels reminds of examples from Gandhara, such as the Sikri stupa, although the panels in the Cave of the Peacock are remarkable by their rigorous chronological arrangement.[20] Similar types of narrative panels have also been found in Andhra.[20]

The dome over the cella is composed of eight pairs of segments filled with a flying apsara among peacock feather. Numerous devatas and Buddhas of the past are painted around the dome.[84]

According to Historian of Art Benjamin Rowland, commenting one of the remaining fragments, the "group of sword-bearing figures are recognizable Indian ethnic types".[91]

Pictures of monks and one Kuchean donor holding a basket of flowers, all labeled with Brahmi inscriptions, appeared on the door wall.[97][98] In the art of Kizil explanatory labels were often added to pictures of donors.[99] On the contrary, such labels were never used for narrative representations.[99]

-

The Seduction of Mara's daughters (left), who are turned into old women (right).

-

The Assault of Mara

-

Musician detail, Cave 76

-

One of the eight pairs of segments from the dome with peacock feathers.

-

Top portion of two of the "peacock" segments.

-

Lower row of panels in the left wall.

-

Central pedestal in the Peacock Cave (total width of 2.18 meters)

The "Cave of the Seafarers" (cave 212, circa 400 CE)

editCirca 400 CE

The "Cave of the Seafarers" (Höhle der Seereise) is dated by Rhies to the early 5th century CE, based on stylistic analysis.[100] Carbon dates are significantly later, circa 561-637 CE.[101] The cave contained long narrative sequences about various paths to enlightenment.[100] Most of the panels are now in the Dahlem Museum.[100] The content of the paintings in the "Cave of the Seafarers" is clearly derived from Gandharan prototypes.[102]

A painter "Rumakama" ( , "the one from Rome"),[103] appears in a Sanskrit inscription in the cave.[101] The inscription, scribbled on the right side of the mural, reads:

"After this painting was done, the one who came from Rumakama (Syria), the painter Manibhadra, did these circles below".[104][105]

According to Grünwedel, "the circles (mandalâni) undoubtedly refer to the edges made of foliage and human skulls", that is the Classical border of acanthus leaves and Buddhist skulls painted along the inferior border of the mural.[106]

The word Rumakama, or Romakam appears in the Kizil paintings as well as in the later Tibetan document, and is thought to refer to a painter who came from the Roman Empire or the Byzantine Empire.[107]

Period 2: "New school" with bolder style (circa 400–500 CE)

editFollowing the earliest "Classical" style of the paintings at Kizil, which was especially elegant and "painterly", with sophisticated shading of the bodies to express sculptural volume,[70] a new school appears with the Cave of the Statues, with works such as the "Cowherd Nanda", which is much bolder, using intense colors (but still limited to browns, greens and oranges), thicker lines and simpler patterns, somewhat like "colored drawings".[70][108] This style is thought to be derived from the confluence of Hellenistic, Iranian and Indian influences under the Kushans, and its main center of creation was at Bamiyan, which became "a kind of parent monastery for the settlement of monks in Central Asia".[109]

This evolution in style is accompanied by a change in the main themes being portrayed. In the Classical period the story of the life of the Buddha and numerous Jataka tales took center stage. Now the main accent is on the sermons of the Buddha, which typically cover the walls of the main cella, together with the appearance of side and rear corridors in which are pictured the events of the death of the Buddha, the Parinirvana.[110][111]

Rhie attributes the sudden variations of styles at Kizil, without much signs of internal evolution (especially in the early stages), to the sudden arrival of new groups of artists from other regions, bringing their own artistic idioms and techniques.[112] This period is also marked by the appearance of the self-portraits of painters in long tunics and highboots armed with short daggers, such as the painter of the Cave of the Statues or the several painters of the "Cave of the Painters", with often their own identifying labels in Sanskrit.[113][114] The clothing style and type of these painters has often been described as Sasanian,[63] but has recently been proposed as being rather Hephthalite, due to the similarities with the Hephthalite figures in Dilberjin Tepe, Balalyk Tepe or Bamiyan, and because the Hepthalites did control the Tarim Basin for nearly a century around this time period.[51][115]

"Cave of the statues" (Cave 77, 375–400 CE)

edit375–400 CE

The "Cave of the Statues"[70] (Statuenhöhle) was a magnificent cave, located next to the "Peacock Cave" (Cave 76). It is a "colossal image cave", with no niche in the main cella, but a podium on which a colossal standing statue of the Buddha probably stood.[70] In an atypical design, the back corridor is quite large and wider than the main cella, with a width of 8.70 meters, for a height of 5.10 meters.[70] Only seven other "Colossal image caves" are known in Kizil, including caves 47, 48, 70, 136, 139, 146.[4] They are characterized by a very tall main cella designed to accommodate a gigantic image of the Buddha, the height of the cella reaching around 5 meters and sometimes as high as 16.5 meters (such as in cave 47), and also a rather tall back room (often around 5–6 meters high).[4]

The numerous statues of the cave were made of clay and straw, fibers or hair for reinforcement, and often dated to the 6th century CE,[120] but now rather dated to 375–400 CE in conjunction with carbon dates.[101][121][7][90] Many of the statues were made from molds, which had Sanskrit names on them, which are probably the names of the crafsmen or the owners.[120]

The cave is a "central pillar" cave, but the roof of the main cella, which formed a vault culminating at around 6 meters, has entirely collapsed. A few paintings remained on the walls of the main cella: they were sermons of the Buddha organized in several rows, the size of each of these pictures being 1.34 m wide and 96 cm high. The sermon images were "of pure Gandhara style".[122] Their style was very close to those of the "Cave of the Painters (Cave 207)", and, according to Grünwedel, "they seem to have been executed by the same hand".[122][123] Albert Grünwedel attributed both caves to the same "Stage I" period (500–600 CE).[38][39]

Several fine fragments of very fine painting have reached us, which are attributed to the Cave of the Statues.[124] Grünwedel explained that only three paintings remained in the cella, all scenes of the sermon of the Buddha:

1) On the right wall of the cella, Grünwedel described the picture of a sermon, with "a youth in light undergarment praying in front of Buddha", corresponding to the picture now described as the "cowherd Nanda", known to have come from the Cave of the Statues.[122]

2) In the opposite location, on the left wall, Grünwedel described a sermon scene in which the Buddha "only had his feet remaining", corresponding to the panel photographed by Charles Nouette in-situ in 1907.[122]

3) Finally Grünwedel described a sermon scene with only a "kneeling adorant" remaining, corresponding to the kneeling Vajrapani, known to have come from the Cave of the Statues.[122]

The style of these panels from the main cella is markedly different from the refined, "classical" style of the side corridor vaults and the back corridor. They suggests different painters and different schools of art. In the cella, the paintings are much bolder, using intense colors, thicker lines and simpler patterns, as in the "Cowherd Nanda".[70] The colors of the paintings in the cella, although more intense, are still limited to browns, greens and oranges.[70] The big eyes and wide eyelids remind of late Kushana works.[70] These new types of paintings suggest the emergence of a bold new style in Kucha around that time.[70]

A painter, holding a cup of paint, and whose clothes "exactly match" the painters in the "Cave of the Painters" (caftan, boots...) is visible in one of the murals of the cave.[113][114] Originally at the front end of the left corridor, behind the first statue, the painting is now located in the Hermitage Museum.[125] Two more devotee figures with the same clothes were located in the back corridor as well.[122]

One of the statues is a man in a particular type of armour with sectioned areas, which used to stand as a protector (possibly a Vajrapani) to the left side of the colossal Buddha of the main cella.[70] This type of armour was in use for several centuries in art of the Northern segment of the Silk Road, and later became prevalent in China.[126] The head is a tentative addition.[127] Lü Guang, a Chinese general sent by Emperor Fu Jian (r. 357–385) of the Former Qin dynasty (351–394), who temporarily conquered Kucha in 383–385 CE, mentioned the powerful armour of Kuchaen soldiers, a type of chainmail and lamellar armour of Sasanian inspiration which can also be seen in the paintings of the Kizil Caves:[61]

They were skillful with arrows and horses, and good with short and long spears. They armour was like chain link; even if one shoots it, [the arrow] cannot go in.

-

Front of the cave. The main cella, about 6 meters in height, has collapsed, and the entrances to the two side corridors are directly exposed.

-

Plan and side view of the Cave of the Statues. The front room, about 6 meters tall, has a huge podium (3.8x1.4 meters) for a colossal statue of the Buddha. The large back room has a rare gabled ceiling.

-

The sermon scene just before the entrance to the left corridor, photographed in-situ by Charles Nouette in 1907

The side corridors are structurally highly sophisticated and remain visible to this day. A low platform runs along the external wall of each corridor, on which rows of statues were displayed, with murals behind them including the figure of the painter in tunic and boots. Above them, the top of each corridor formed a high vault, equipped with a lunette on the southern side, and decorated over its length with rows of devatas behind a balustrade, standing around a Buddha Maitreya, and on top of them landscapes with rhombus losange designs with monks, animals, trees and ponds, of the type seen in vault of the Cave of the Hippocampi (Cave 118).[70][128][129]

The back corridor, also visible today, is quite unusual, as its vault is trabeated, formed of three flat longitudinal surfaces, on which figures of devatas are aligned like a deck of cards.[70][129] On the bench along the back wall, stood a colossal reclining Buddha image in a scene of the Parinirvana, with elegant flying devatas hovering over the Buddha.[70][128] Remains of female statues seated on the back bench were visible, with, at their, feet the bust of a man-elephant.[128]

The style of the paintings in this cave, especially in the side and back corridors is very elegant and "painterly", with sophisticated shading of the bodies to express sculptural volume.[70] It is quite similar to the style of the Cave of the Hippocampi (Cave 118), and may belong to the same school.[70] This refined style contrasts with the style of panels in the cella, the "Cowherd Nanda", which is much bolder, using intense colors (browns, greens and oranges), thicker lines and simpler patterns.[70] This divergence suggests that the "Cave of the Statues" may be transitional between these two early styles.[70] Later caves such as the Cave of the Musicians point to an even more different style, using vivid colors and Ligne claire sharp lines to delineate body shapes together with the abundant use of intense blue pigments, with different roots inspired by the Western art of the 4th century CE.[70]

-

Remains of statues in the left corridor ("2" in the map). The painter in caftan is in the corner behind the first statue from the left.[130] The statues too were painted.

-

Cave of the Statues, back room mural, over a reclining statue of the Parinirvana Buddha.[131]

-

Left corridor, devatas standing at a balcony (detail).

-

Ceiling of the back corridor (detail)

"Cave of the Painters" (Cave 207, dated 478–536 CE)

edit(Cave 207, 478–536 CE)

The "Cave of the Painters" (Malerhöhle, 画家窟, Cave 207)[134] is one of the earliest caves of Kizil, and one of the most beautiful.[135] The cave contained a statue of the Buddha against the rear wall of the cella, and a barrel-vaulted ambulatory surrounded it.[135] The main cellar contained nine murals of the preaching Buddha on each side wall.[135]

The name of the cave comes from the numerous self-portraits of painters standing at the side of the murals, holding paint cupellas and brushes.[135] Several of the painters have a label, such as the written label in Sanskrit (Gupta script): "Painting of Tutuka" ( Citrakara Tutukasya) next to the painter in question.[136] "Citrakara" is not Tocharian, but Sanskrit (and later Hindi, चित्रकला) for "painter/ painting".[137][138][139][140] In the art of Kizil identifying labels were often added to pictures of donors, but never to narrative scenes.[99]

Paleography, stylistic analysis and carbon dating combine to give a date of circa 500 CE for these paintings.[135] Some stylistic elements have a strong Classical touch, such as Roman-style friezes at the top of the walls, over scenes of the Buddha.[132]

The Cave of the Painters, as some other caves at Kizil, depicts men in caftans with a triangular collar on the right side, and a unique hairstyle. Another marker is the two-point suspension system for swords, which seems to have been a Hephthalite innovation, and was introduced by them in the territories they controlled.[51] These paintings appear to have been made during Hephthalite rule in the region, circa 480–550 CE.[51][115] The influence of the art of Gandhara in some of the paintings at the Kizil Caves, dated to circa 500 CE, is considered as a consequence of the political unification of the area between Bactria and Kucha under the Hephthalites.[69]

The paintings of the Caves of the Painters have been carbon dated to 478–536 CE.[101] Albert Grünwedel in 1912 considered that the murals of the "Cave of the Statues" had been "made by the same artists as those of the Cave of the Painters", and that they were in "pure Gandhara style".[141] Also, a self-portraited painter in the Caves of the Statues, holding a cup of paint, has clothes which "exactly match" those of the painters in the "Cave of the Painters" (caftan, boots...).[113][114] The clothing style of the painters at Kizil has often been described as Sasanian,[142] but is now rather considered as Hephthalite due to the similarities with the figures in Bamiyan, Dilberjin Tepe or Balalyk Tepe.[51][115] Grünwedel attributed both caves to the same "Stage I" period (500–600 CE).[38][39]

The main cella contains 18 scenes of the Buddha preaching.[143] The niche must have contained a monumental statue of the Buddha, and paintings related to the Indrasala Cave narrative.[143] The ceiling is prismatic, reproducing a type of architecture known from Bamiyan.[143] The right corridor contained murals related to the War for the Relics and the Sharing of the relics of the Buddha, one of them showing armoured warriors on horses.[143] The murals of the back corridor were almost entirely gone by 1912. Only a few traces remained, suggesting scenes of the Parinirvana.[143] The left corridor had a beautiful mural showing a monk transmitting the teachings of the Buddha to a kneeling royal family, whether the mural in front of it on the external wall was entirely gone.[143]

Similarities have been noted between the paintings of the Cave of the Painters and those of Dilberjin Tepe and Penjikent of the 5th–6th centuries.[144]

-

Cave of the Painters, plan

-

Self-portraits of the painters at Kizil. Labels in Sanskrit (Gupta script): "Painting of + (name)"

-

Mural in the Cave of the Painters, with painter in caftan in the lower right corner, circa 500 CE.[145][146] He has a label written in Sanskrit (Gupta script): "The Painter Tutuka" (Citrakara Tutukasya).[136] "Citrakara" (चित्रकला) is Sanskrit and Hindi for "painter/painting".[137][138][139][140] Photograph and drawing from 1912, and current state in-situ.[147]

-

Mural with warriors in the right corridor, outside wall: the War for the relics of the Buddha.[143] They wear lamellar helmets, and their sword guards have typical Hunnish designs of rectangle or oval shapes with cloisonné ornamentation:[47] Weaponry can be dated to the 5th century CE.[47] The mural was very clear, but disintegrated upon removal by Grünwedel: only a few fragments remain in-situ.

-

The sharing of the relics of the Buddha by the Brâhmana Drona, to eight kings (four are visible). Relief from the right corridor, inside wall.[143]

-

Detail of a Devata (right wall, top tier, left scene)

Cave 60: "Largest Cave"

editCave 60, also called the "Largest Cave", is a cave which was expanded over several periods, and still contained a few paintings belonging to the refined style of the Classical First Period, while most of the paintings are from the later Second Period.[148] The cave is known for its portrait of royal donors, characteristically accompanied by a label in Brahmi script.[148] This is the only known possible instance of a portrait of royal donors in a painting of the First Style, whereas they occur very often during the second period.[148] The style of painting is very similar to that seen in the Cave of the Painters (Cave 207).[148] The hairstyle of the male donor is quite similar to that of the famous painter in the Cave of the Painters.[148]

The cave is also remarkable for the presence of Sasanian-style ducks in a bead roundel frames, a well-known motif which spread through Central Asia, and is known from the dress of a Central Asian ambassador from Afrasiab.[149] This motif was likely painted later than the portraits of the royal donors.[148]

Second Indo-Iranian Style: strongly contrasted "blue and green" paintings

editThe "Second Indo-Iranian style" evolved with a few intermediate stages, expressing continuous influence from India, combined with influence from the Eastern Iran sphere, at that time occupied by the Sasanian Empire and the Hephthalites, with strong Sogdian cultural elements.[48] The Hephthalites lost political power circa 550 CE after being defeated by the Sasanids and the Western Turks, but they remained influential for a long time, having fragmented into semi-independent Principalities.[150][151] Sogdia, at the center of a new Silk Road between China to the Sasanian Empire and the Byzantine Empire became extremely prosperous around that time.[152]

Central-Asian stylistic elements

editThis style is characterized by strong Iranian-Sogdian elements probably brought with intense Sogdian-Tocharian trade during the period, the influence of which is especially apparent in the Central-Asian caftans with Sogdian textile designs, as well as Sogdian longswords of many of the figures.[66] Other characteristic Sogdian designs are animals, such as ducks, within pearl medallions.[66] Indo-Iranian influence also appears in mythological figures, such as the bird Garuda with snakes in its beak, the wind god Vayu, the sun god Aditya or the moon god Chandra.[66]

The use of strongly contrasted "blue and green" colours, made possible by the importation of lapis lazuli blue pigments from Central Asia, and the drawing of a line for contours, are characteristic of this style.[48][67] This style, exemplified by the Cave of the Musicians, using vivid colors and Ligne claire sharp lines to delineate body shapes, seems to be inspired by the Western art of the 4th century CE, and is very different from the style of the Kizil caves of the earlier period, which on the contrary is very elegant and "painterly" with nuanced colors and sophisticated shading of the bodies to express sculptural volume, and which probably points to different artistical roots.[70] Still no East-Asian influence is visible in these paintings.[48]

-

Sasanian-style medallions in Cave 60, Kizil Caves.

-

Jivajivaka two-headed bird, in blue-and-green style. Kizil Cave 38.

-

Sun God Aditya on his chariot, Cave 171

-

Cave 38, moon symbol

Period 1: Initial transitional style

editThe first period consist in a short interval of transitional style, in which paintings remain subtil and rather nuanced, but blue pigments have started to appear. The Cave of the Devil C (Cave 198) and Cave of the Devil A (Cave 199), as well as the Cave with the Steps (Cave 110) and sometimes the Red-domed Cave A (Cave 67) are considered as the first period of this new style.[48]

-

Lunette scene. Cave 198

-

Mural, Cave 198

-

Monks and devotees, Cave 199

-

Murals with Princes, Cave 199

-

Devotee (right) making an offering to the Buddha, Cave 110

Period 2: main stylistic period

edit"Cave of the Musicians" (Cave 38)

editAccording to Rhie, the "Cave of the Musicians"[153] is probably the earliest of the "central pillar" caves at Kizil, dated to the mid-4th century CE, and its iconography is also among the earliest.[154] Carbon testing by Su Bai gave dates ranging from 310 +/-80 CE to 350 +/-60 CE (i.e. a maximum range of 230-410 CE).[17][47][65] Huo and Wang attributed the cave to the Second Period, giving it a date from mid-4th to late 5th century (circa 350–499 CE).[17] The traditional German datation estimated the cave to be from the 600–650 CE period, and presented it as an example of the later "Blue-green style", said to succeed chronologically the "Orange-green style" group.[17]

The so-called "central pillar" which appears on a plan is actually not a pillar at all but only the rock at the back of the cave, into which was bored a circular corridor allowing for circumambulation.[17] There is a niche in the "central pillar" designed to house a statue of the Buddha, and two other niches on each side of the main entrance, and niches in the back corridor.[17] The central niche probably depicted the Buddha meditating in the Indrasala Cave, with a background decoration of a mountain, a recurring central theme at Kizil.[17] Maitreya, the Buddha of the future, in the Tusita Heaven, appears in a beautiful mural over the exit door.[17] Structurally, the cave remains relatively simple, as it does not have an anteroom or vestibule.[17]

The style of the paintings is derived from the Art of Gandhara and Kashmir, the Art of Mathura and early Gupta art, with striking influences from Roman art and the art of Palmyra.[17][154] Kumārajīva is known to have travelled repeatedly between Kucha and Kashmir around this time, and he may have been instrumental, among many others, in the transmission of this art.[17] The structural prototype of the cave may be Kara Tepe in Bactria.[154] The flat, well-delineated surfaces of the paintings remind of the Roman Opus sectile technique, which prospered circa 331–359 CE.[17]

-

Entrance of Cave 38

-

Ceiling, photographed in 1907 by Charles Nouette

-

"Merciful Turtle King" from Buddhist Jataka tales. Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg.

-

Warrior in armour, ceiling of Cave 38.[156]

-

Trader making a dedication to the Buddha, Cave 38.[157]

-

Jataka scene on the ceiling: Sabu leading the way of the traders, Kizil Cave 38 "Cave of the Musicians"

-

Kizil Cave 38, ceiling.

Cave 14: Central Asian traders

editCave 14, a small and nearly square room with a vaulted ceiling (2.17x2.17 meters), is considered as later than the "Cave of the Musicians", and dated to the late 4th century CE to early 5th century CE, circa 400 CE, by Rhie.[89][158] The cave has many designs showing Central Asian traders encountering various dangers on their way, such as being lost in the dark, and being saved by the Dragon-King Mabi.[159] Cave 14 is considered as an important historical marker for the dress styles or the armour types worn by some of the figures.[158]

-

Kizil, man in armour, cave 14. 智马舍身救王命故事 "The story of the smart horse who sacrifies himself for the king".

-

Dragon-King Mabi saving traders, Cave 14

-

Deity on elephant, Cave 14

-

Ceiling of Cave 14, traders galloping in the dark (bottom), among vignettes alluding to Jataka tales.

Cave 17: Tocharian royalty (circa 500 CE)

editCave 17 (Cave of the Bodhisattva Vault) is large "central pillar" cave located near Cave 14, and high up on the rock to the right of Cave 8.[164] It was probably the main cave of the group of caves from 14 to 19, which also includes several undecorated living quarters or viharas, and was dedicated to religious services. Su Bai dates Cave 17 to the Second Stage (395–465 CE -+65), together with Cave 14. Luo and Wang date it to 465 CE +-65.[7] Rhie attributes Cave 17 to circa 500, based on stylistic considerations.[165] It is a "central pillar" cave, with a small, very colorful, square cella (3.80x3.90 meters) with a vaulted ceiling, a central pillar with two side corridors, and a back room.[164] These caves were possibly small chapels to nearby viharas.[89]

In Cave 17,[166] on the lower left panel of the entrance wall, appeared a Royal family, composed of the King, Queen and two young Princes. They are accompanied by monks, and men in caftan. The relief is now in the Hermitage Museum.[160] The King wears a crown and a triple halo, with Sasanian-type royal ribbons.[163] He wears a long white caftan decorated with small diamond designs, and has long boots. His right hand is in front of his chest, holding an incense lamp,[163] and he holds an akinakes sword and a red bag in the left hand.[163][167] The end of a long knight's sword is visible behind the first boot.[163] The king can be identified as a Tocharian king of Kucha.[162] His Queen wears a long robe, and his two sons, Princes, wear ornate caftan and are fair-haired.[163]

According to Historian of Art Benjamin Rowland, the portraits in Kizil show "that the Tocharians were European rather than Mongol in appearance, with light complexions, blue eyes, and blond or reddish hair, and the costumes of the knights and their ladies have haunting suggestions of the chivalric age of the West".[168] The Chinese named Kuchean kings by adding the prefix "白", meaning "white", probably pointing to the fair complexion of the Kucheans.[169] The Chinese Monk Xuanzang in 645 CE, noted that "they clothe themselves with ornamented garments of silk and embroidery".[170]

This cave also shows Central Asian traders encountering various dangers on their way, such as being lost in the dark, and being saved by the Dragon-King Mabi. Another is the story of the good merchant Sabu (萨缚), who, in order to show the way to a party of 500 merchants lost in the darkness, puts his own arms on fire to use them as torches, and successfully rescues them. The story appears in numerous paintings, in which the merchants are in Central Asian garb and accompanied by camels, and Sab has the attributes of a Bodhisattva.[159]

Cave 17 is contemporary with the earliest decorated Mogao Caves near Dunhuang (caves 268, 272 and 275), which were built and decorated by the Northern Liang between 419 and 439 CE, before the invasion of the Northern Wei. They have many stylistic characteristics in common.[171][172]

-

Plan of Cave 17

-

Two-headed dragon capturing traders, Cave 17

-

Sab leading the way for the 500 traders, Kizil Cave 17.

-

Attendants to the King, Cave 17, Kizil

-

Vairocana Buddha, right corridor, Cave 17

"Cave of the Sixteen sword bearers" (Cave no. 8, 432–538 CE)

edit(Cave 8, 432–538 CE)

The "Cave of the Sixteen sword bearers" ("Höhle der Schwertträger", 十六带剑者窟) is a famous cave with a series of murals showing swordsmen wearing caftans and armed with long sword and daggers. These murals have been carbon dated to 432–538 CE.[173][60] The swordsmen have also been dubbed the "Tocharian donors".

The interpretations of the nationality or ethnicity of the donors have varied. Some authors claim that the donors are indeed Tocharians, an elusive people of the Tarim Basin who spoke the well-documented Tocharian language, the easternmost Indo-European language.[175] According to this thesis, the donors in the murals are of the Indo-European type, wearing Iranian-style clothes and reddish hair.[175]

A more recent interpretation is that the sword-bearers are actually Hephthalites, who are known to have occupied the Tarim Basin from 490 to 560 CE, precisely at the time the paintings were made.[51][174] Kucha was specifically part of their dominion between 502 and 556 CE.[176] The clothing style, the iconography and the physionomy of the donors are said to be extremely close to those depicted in the paintings of Tokharistan (Bactria), the center of Hephthalite power, at sites such as Balalyk tepe or Dilberjin Tepe.[51][174] In particular, the coat with single folded lapel is considered as a result of Hephthalite influence, whereas traditional Kuchean coats had two lapels.[177] At present, the most prevalent opinion among academics seems to be that the Hephthalites were initially of Turkic origin.[178]

Similar donors can be seen in the Kumtura Caves.

In the "Cave of the Sixteen sword bearers", the murals of the sixteen sword-bearers are located in the lateral left and right corridors around the central pillar, simulating a procession of devotees.[179] The sides of the main room are occupied by panels showing groups around seated Buddhas, while the vault is decorated with a myriad of small Buddhas with emanating flames.[179]

-

Cave of the 16 Sword-bearers, at the west end of the Kizil cave complex

-

Cave of the 16 Sword Bearers (plan)

-

One of the sword-bearers, in right-lapelled caftan.

-

Cave 8, sword-bearer detail

-

Swordbearer and servant

-

Man with a turban, from the side wall of the main cella.

The rear corridor, forming a back-room behind the central pillar, is a barrel-vaulted rectangular room with the two corridors for side access. It was decorated by many spectacular murals, including a large mural showing the sharing of the relics, with soldiers in armour riding horses and elephants (β on the plan).[179][180] The vault was lavishly decorated with flying asparas holding musical instruments. The back wall had a depiction of the Parinirvana with a reclining image of the Buddha, and asparas flying over. The murals were photographed in black and white in-situ by Charles Nouette in September 1907, but all of them were later taken to Germany by Von Le Coq. A reconstruction of the rear corridor was recently built in the Museum für Asiatische Kunst.

-

Back corridor room of the Cave of the Sixteen Swordbearers, looking towards the main cella (reconstitution).

-

Vault decoration over the mural of "The War of the Relics": on-site photograph in 1907 by Charles Nouette, and removed color panels at the Dalhem Museum.

-

Mural on the inside wall of the rear corridor (β on the plan). The kings around the Brahmana Drona, and below, soldiers on elephants and horses. War of the relics.

-

Armoured men on horses and elephants, in the rear corridor, War of the Relics scene (details)

Cave 181: Cave of the High Place in the Small Valley

edit(Cave 181)

The Cave of the High Place in the Small Valley (Cave 181), also called the "Highest Cave",[181] is described extensively by Albert Grünwedel, as a particularly interesting cave of the small ravine.[182] He explains that the cave is located high up on the right side of the ravine, which accounts for the fact that its murals have been preserved from the usual iconoclastic vandalism: the faces in particular are well preserved.[182] Also, the murals did not use gold foils for decoration, which reduced the incentive for theft.[182] In his plates, Grünwedel illustrates the murals of the cave, where he names the cave by its official name: Hochliegende Höhle der 2. Schlucht ("Cave of the High Place in the 2nd Valley"),[183] which is the German name for cave 181.[184]

Grünwedel explains that the structure of the cave is extremely rare, as it is not a barrel-vaulted cave: instead, the ceiling has the shape of a tent.[185] The flatness of the sides of the tent-like ceiling is the reason why Grünwedel was able to remove easily most of the ceiling paintings in large panels, something which is impossible with the strongly curved surface of a barrel-vaulted ceiling.[182] The tent-like ceiling is bordered by a row of seven bejewelled princes on each side.[182]

The side wall depict rather tumultuous scenes of the sermon of the Buddha, no fewer than eight of them, with a multitude of attendants in various attitudes and clothing.[186] The entrance wall had paintings of Tocharian donors and monks on both side.[182] Above the entrance was the usual painting of Maitreya with surrounding Devaputras.[182] The side corridors had paintings of Jataka stories, while the back corridor behind the niche had a bench or pedestal along the back wall for the display of the Parinirvana of the Buddha, with deities flying over.[182] On the opposite wall was a scene of the Cremation of the Buddha.[182] Grünwedel sent most of the murals to Germany.[182]

A headless wooden statue of a Dhyanasana Buddha, about 164 cm tall, was found in the cave.[187]

The murals and the paintings of the ceiling are generally attributed to Cave 181,[188][189] but some authors attribute them to Cave 178 instead.[190] To add to the confusion, von Le Coq wrote in 1924 that the paintings of the ceiling actually came from barrel-vaulted Cave 184, and he claimed that Grünwedel, who accomplished the removal of the murals in 1906–1907, wrongly described the vault as being "tent-like".[191] Access to cave 181 has remained difficult, and it has also been claimed that it was never painted.[192][193]

-

Flat mural of the right half of the ceiling. It is about 4 cm thick, and weight around 400 kg. Dahlem Museum.[194]

-

Sab leading the way to a trader with a camel.

-

The Buddha and attendants

Period 2 (later phase, 500–700 CE)

edit(Cave 224, 550–600 CE)

The 3rd phase covers a period from the mid-6th century CE to the early 7th century CE. Carbon testing from this period gave dates ranging from 545 +/-75 CE to 685 +/-65 CE (i.e. a maximum range of 470–750 CE).[65] Maya Cave (n.224) is one of the famous caves from this period. Historically, the paintings of this period seem to correspond to the Turk expansion, following their uprising against the Rouran Khaganate in 552 and their subsequent territorial expansion.[47] This can also be seen the style of armour of some of the soldiers in the murals, especially with their pear-shaped helmets.[47]

Vivid colors are used, with great contrast, sometimes quite unnaturally and in a garish manner. A lot of lapis lazuli blue is incorporated in the palette of this artist.[48] Skin color or hair color are often quite unnatural.[48] Backgrounds often have plenty of flowers, fruits or leaves. Ornaments are often extravagant.[48] Again, no East-Asian influence is visible in these paintings.[48]

Māyā Cave (Third complex, cave 224, c.550–600 CE)

editMaya Cave (Cave 224) of "III Anlage" is one of the most famous caves of the Third Period. It is dated to circa 550–600 CE, and possibly follows the events of the Turk uprising against the Rouran Khaganate in 552 CE and the subsequent Turk expansion.[195] The helmets of the Knights depicted in some of the murals have been said to be characteristic pear-shaped segmented helmets of the Turkic type.[195][196]

A famous mural of the Mourning of the Buddha at his Cremation appears in Maya Cave (224), from the rear passage of the cave, with various figures in ethnic costumes.[197] Three of the men among the mourners cut their forehead skin or chest with their knives, a practice of self-mutilation practiced by the Scythians.[197] One of the mourners if is thought to be a Turk.[198][199]

-

King Ajatasaru, His Queen, and His Minister Varshakara, Kizil, Maya Cave, (Cave 224).

-

The War of the Relics, back corridor of Maya Cave (224).[195]

-

Knights in Kucha, following the events of 552 CE Turk uprising and the subsequent Turk expansion. 2nd half of the 6th century CE. The helmet is a characteristic pear-shaped segmented helmet of the Turkic type.[195][196]

-

Tocharian Prince mourning the Buddha.

-

A monk from "The First Sermon", right corridor painting.

Māyā Cave (Second complex, Cave 205, end 6th century CE)

edit(Cave 205, 600 CE)

Maya Cave of "II Anlage" (Cave 205) has been carbon-dated to the 6th–7th century CE.[90] The cave has an inscriptions in Sanskrit mentioning the King of Kucha Anantavarma. He is shown accompanied by two armed attendants.[201]

"When Anantavarma, the great king (maharaja?) of Kucha, saw the letter of Ilmonis, the dedication and the little container of musk, he had honor done to the Buddha."

— Albert Grünwedel translation.[201]

A Prince appears with his wife in the adjacent frescoes, mentioned in a nearby inscription as the future king Tottika and his princess Swayamprabha.[202]

This cave has been rather precisely dated to the end of the 6th century CE, based on the names of the rulers found in the inscriptions, particularly King Tottika and his wife Svayamprabha (a Sanskrit name), who also appear together with Suvarnapushpa (known to have ruled 600–625 CE) and his son Suvarnadeva in the inscriptions on the walls of the Red-dome Cave.[203] The epigraphy also suggest dates later than the Cave of the Painters, with its more ancient inscription about the "painter Tutuka".[204]

-

Presentation of the Parinirvana, Cave 205

-

The Monk Ajnatakaundinya, Maya Cave, Site 2, (Cave 205)

-

Cremation of the Buddha

-

Medidating Mahakasyapa in his patched robe, ceiling detail, Cave 205.[207]

-

The inscription in Sanskrit mentioning Anandavarman

Red-dome Cave 67: more royal dedications

editAnother nearby cave, the Red-domed Cave A (Cave 67) also has inscriptions mentioning a list of donors including a queen and six kings, among them Suvarnapuspa (ruled 600–625 CE) and his son Suvarnadeva (ruled 625–648 CE).[202][208][209] Also included in the inscriptions are the names of King Tottika and his wife Svayamprabha (a Sanskrit name), who also appear in the Maya Cave of the Second Group (Cave 205), suggesting proximity in time of these two caves.[203] The epigraphy also suggest dates later than the Cave of the Painters, with its more ancient inscription about the "painter Tutuka".[204]

The Red-dome cave contained a library in which were found very old manuscripts, including one of the oldest known manuscripts in Sanskrit.[33]

-

Plan of the Red-domed Cave A (cave 67)

-

View of the dome and paintings.

-

Princes and Princesses in the Red-domed cave

Cave 69: portrait and dedication of the king of Kucha (securely dated to 600–647 CE)

editThis period has the only known secure dating in the Kizil Caves: Cave 69 has a painting of a royal Kuchean couple with an inscription in the halo of the King: "Temple Constructed for the Benefit of Suvarnapushpa by His Son", Suvarnapuspa having ruled between 600 and 625, and his three sons died before 647 CE according to Chinese sources.[210][211][212]

When he visited Kucha in 630 CE, the Chinese monk Xuanzang received the favours of Suvarnadeva, the son and successor of Suvarna-puspa, and Hinayana king of Kucha.[213]

Xuanzang described in many details the characteristics of Kucha (屈支国 qūzhīguó, in "大唐西域记" "Tang Dynasty Account of the Western Regions"), and probably visited Kizil:[214][215]

1) "The style of writing is Indian, with some differences"

2) "They clothe themselves with ornamental garments of silk and embroidery. They cut their hair and wear a flowing covering (over their heads)"

3) "The king is of Kuchean ("屈支" qūzhī) race"[216]

4) "There are about one hundred convents (saṅghārāmas) in this country, with five thousand and more disciples. These belong to the Little Vehicle of the school of the Sarvāstivādas (Shwo-yih-tsai-yu-po). Their doctrine (teaching of Sūtras) and their rules of discipline (principles of the Vinaya) are like those of India, and those who read them use the same (originals)."

5) "About 40 li to the north of this desert city there are two convents close together on the slope of a mountain".[101]

These events were soon before the Tang campaign against Kucha in 648 CE.[213]

-

A painting in the left corridor, Cave 69

-

Kuchean devotees, Cave 69, Kizil

-

King Suvarnapuspa and his Queen (龟兹国王与王后供养像) in Cave 69 (dated 600-647 CE per Chinese sources).[217]

Period 3: final narrative evolution

editThe final stage at Kizil is Period 3 of the Second Indo-Iranian Style.[54] Towards the end of its florescence, Kizil saw the emergence of the domed central pillar cave, a type of "central pillar" structure, with niche and circumambulating corridor, but with a very uncharacteristic near-cubic main cella crowned by a magnificent cupola decorated with divinities.[218] The style of painting is very refined, and can also be seen in some other caves in the region such as in Kumtura. The iconography too has evolved, with a cosmological Buddha becoming omnipresent and majestic, often surrounded by myriads of emanations of smaller Buddhas.[218] This exceptional and very refined type of cave is exemplified by Cave 123, the "Cave with the Ring-Bearing Doves".[219] It represents a final narrative evolution, in which the figures of the cosmological Buddha predominate, while secondary figures and stories take an ever-smaller role.[220]

"Cave with the Ring-Bearing Doves" (Cave 123)

edit(Cave 123, 600–650 CE)

The "Cave with the Ring-Bearing Doves" (Cave 123) had a type of "central pillar" structure, with niche and circumambulating corridor, but with a very uncharacteristic cubic main cella crowned by a magnificent dome decorated with divinities.[218][221] The main cella forms a square vestibule or main hall (3.42 x 3.42 meters) in front of the pillar forming the back wall, the vestibule being surmounted by a decorated dome. The prototype for the dome decorated with standing Buddhist deities is to be found in Group C of the caves at Bamiyan.[222] It can also be seen in some other caves in the region, such as in Kumtura.

The cave is named after a pattern of "flying geese holding a wreath" (or ring). This pattern is also known from Cave 69, which is dated to 625–647 CE because of the depiction and inscription of a historically identified king. Because of this marker, Cave 123 may be dated to the same period.[223]

Two monumental Buddha images occupy the sides of the main cella. They have full-body "mandorla" halos filled with a multitude of sitting or standing Buddhas.[224] These monumental images represent the second Great Miracle of the Sakyamuni Buddha at Shravasti.[219] The myriads of Buddhas emanating from him, each standing on a lotus, are a result of his deep meditation at Shravasti, as recounted in the Divyavadana.[219] This understanding of the Great Miracle is most prominent among the Sarvastivadin and the Mulasarvastivadin.[219] The two monumental Buddhas are surrounded by attendants, some light-skinned and some dark-skinned, and a Vajrapani.[219]

The side corridors also have similar Buddha images, but this time with a supplementary decorated band around the Buddha, which is filled with a row of ring-bearing doves, hence the name given to the cave.[224] All Buddha images are surrounded with numerous attendants, Devatas and Vajrapanis.[224]

The paintings were in great part brought to Europe by the fourth Royal prussian expedition to Central Asia of 1913–1914 led by Albert von Le Coq.[225] The cave was reconstructed in Berlin around 1928, but suffered damage during the war.[226] It has been reconstructed again recently in the Museum für Asiatische Kunst. The painting of the left side wall remains in-situ, quite damaged.[227][228]

-

Cave 123, with collapsed front antechamber.[229]

-

Cave 123, as recorded by Charles Nouette in September 1907 (composite)

-

Decorative dome over the niche. "Cave with the Ring-Bearing Doves". Ethnological Museum of Berlin

The cave is quite outstanding and refined, either in terms of architecture and decoration, and departs from the mainstream of other caves at Kizil. Marianne Yaldiz has called it "One of Xinjiang's Mysteries".[230] Untypically, the narrative scenes are placed over the entrance, taking second position to the monumental standing Buddhas of the side wall. This is a layout which became popular farther east in Gansu.[220] In a final narrative evolution, the cave magnifies the figure of the Buddha, and gives an ever smaller role to secondary figures and stories.[220]

-

The Buddha with his thousand emanations

-

Entrance wall, Sermon of the Buddha.

-

Bodhisattava over the niche.

-

Cave 123, Dome detail.

-

Cave 123, Dome detail.

Other caves of the third period

editThe Center Cave (Cave 186), the Third to Last Cave (Cave 184) and the Third Cave from the Front (Cave 187) are also considered as representatives of this third period.[54]

-

Monks and donors, Cave 186

-

Cave 186, group.

-

Cave 186

-

Monks and devotees, Cave 184

-

Devotees, Cave 184

Uighur-Chinese Style (8th–9th century CE)

editA 4th period, also described as "The third style" receives strong influence from Chinese painting, a result of the artistic activity and expansion of the Tang dynasty.[231] The civilization of Kucha, with the whole Tarim Basin from Turfan to Khotan, fell to the Chinese punitive invasion of 648 CE, putting an end to the Indo-Iranian styles of Kucha.[232] Ashina She'er, the East Turkic general leading the Tang dynasty expeditionary corps, ordered the execution of eleven thousand Kuchean inhabitants by decapitation. It was recorded that "he destroyed five great towns and with them many myriads of men and women... the lands of the west were seized with terror."[233]

Two caves at Kizil have art of the Tang period: cave 43 and cave 229.[234] In nearby Kumtura and in Turfan, Chinese styles now prevailed.[232]

In 670 CE, the Tibetan Empire conquered most of the Tarim Basin, including Khotan, Kucha, Karashahr and Kashgar, which they kept until the Chinese took back the control of the area in 692.[235]

In 753 CE, the northern part of the Tarim Basin was taken over by the Turks of the Uyghur Khaganate, based in Turfan.[235][236] A new Tibetan conquest took place in 790 CE.[235] By 900 CE, the area was under Muslim domination.[235]

Texts and inscriptions

editLove poem