This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages)

|

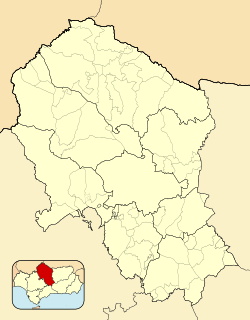

Lucena (Spanish pronunciation: [luˈθena]) is a municipality of Spain belonging to the province of Córdoba, in the autonomous community of Andalusia.

Lucena | |

|---|---|

| |

| Coordinates: 37°24′32″N 04°29′07″W / 37.40889°N 4.48528°W | |

| Country | Spain |

| Autonomous community | Andalusia |

| Province | Córdoba |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Juan Pérez Guerrero |

| Area | |

• Total | 351 km2 (136 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 485 m (1,591 ft) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

• Total | 42,530 |

| • Density | 120/km2 (310/sq mi) |

| Demonym | Lucentinos |

It is the second-most populated municipality in the province.

A major Jewish centre from the 9th to the 12th centuries, Lucena was remarked for having a Jewish-majority population.

Geography

editLucena is located in the transition zone between the campiña in the Guadalquivir Depression and the Subbaetic system, at an altitude above mean sea level slightly below 500 meters.[2] The Subbaetic system include neighboring subranges such as the sierras of Cabra, Carcabuey, Pollos, Horconera, and Rute.[2]

History

editDespite claims of association with earlier locations (such as ancient Erisana), Lucena did not enter historical record until the period of Islamic rule.[3] It was first mentioned in a 853 responsum which described Lucena (Alisana), then part of the Emirate of Córdoba, as "a city of many Jews" with "no Gentile in its midst".[4] Some gravestones unearthed in the Jewish necropolis of Lucena have been tentatively dated to the 9th–10th centuries.[5] During Islamic rule, Lucena belonged to the Kūra (district) of Cabra.[6] Already in the 10th century, Lucena's jewry competed in importance with Córdoba's.[7] Amid the fitna of al-Andalus that brought the collapse of the Caliphate of Córdoba in the 11th century, Lucena became part of the Zirid Kingdom of Granada.[8]

At the beginning of the 11th century, several important Jewish scholars lived in Lucena. Isaac Alfasi founded a large Talmudic academy in Lucena, and here also Isaac ibn Ghayyat, Isaac ibn Albalia, and Joseph ibn Migash were prominent.

Jews in Lucena drastically decreased in number upon the onset of Almoravid and Almohad rule, with Jews fleeing to locations of the Iberian Peninsula's Christian North (such as Toledo),[9] being forcefully converted to Islam or being deported as captives to North Africa.[10] The Almohad conquest of Lucena took place in 1148.[11] Jewish commentator Abraham ibn Ezra lamented the fall of Lucena to the Almohads as if it were a sort of a minor Jerusalem.[12] Whatever the case, Lucena effectively ceased to exist then as a Jewish centre.[13]

Lucena was conquered by the Crown of Castile in 1240. It was thereby donated to the Bishop and the Cabildo of the Cathedral of Córdoba in 1241.[14] Lucena remained under Cordobese bishopric control until 1342, when it became a stately possession under Leonor de Guzmán.[15] It was thus granted a fuero similar to Córdoba's in 1344.[15] A borderland town with the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada for the rest of the middle ages, it became a possession of a branch of the House of Fernández de Córdoba in the late 14th century.[16]

Population boomed in the early 16th century, growing from 1,300 inhabitants in 1495 to about 8,172 in 1530,[17] owing to the disappearance of the frontier condition in the wake of the Conquest of Granada in 1492.[18] Lucena was then settled by numerous converso families, contributing to the demographic growth.[19] Conversos leaned on serving the ruling aristocracy, the Marquises of Comares.[20] Lucena was granted the title of ciudad ('city') in 1618.[21]

Portuguese immigrants with a converso background such the Rodríguez settled in Lucena in the early modern period linking with the local Carmona-Castillo converso lineage.[22] Similarly to the situation in other towns of the Kingdom of Córdoba, the Portuguese involved in sectors of the local economy such as the textile industry and slave trade.[23]

The chief industries are the manufacture of furniture, industrial refrigerators, wine, bronze lamps and pottery, especially the large earthenware jars (tinajas) used in the past throughout Spain for the storage of oil and wine, some of which hold more than 300 gallons. Matches also used to be made there. There is considerable trade in agricultural produce. The horse fair in September was famous throughout Andalusia, but since the last decades of the 20th century there is only a fair like in most towns in Andalusia.

Easter celebrations - Semana Santa

editEaster, or Semana Santa, is the most important celebration taking place yearly in Lucena, just like in most parts of Spain. However, Lucena's Semana Santa, declared of Special Tourist Interest, is well known for its peculiar and unique way of porting or carrying the "pasos" or processions. All these "pasos" are formed by at least one sculpture, most of the time hundreds of years old. They are carried on shoulders as nowhere else in Andalusia, all porters uncovered (unlike the Seville way) and at the same level (unlike the Málaga way). The way processions are carried in Lucena is called "santería", and it is a particular trait to the city. Santería can best be appreciated on Easter Thursday (Jueves Santo) where 9 "pasos" take the streets. Not to be missed are the Cristo de la Columna, by most renowned sculptor Pedro Roldán, created in 1675, and the impressive Cristo de la Sangre, brought from the Spanish Americas in the beginning of the 17th century.

Best Semana Santa days in Lucena are Palm Sunday (5), Tuesday (7), Thursday (9) and Saturday (1).

Palm Sunday sees 5 "pasos" on the streets belonging to 3 different congregations and churches. They come together at a certain point creating a single procession. Palm Sunday highlights the Cristo de la Bondad and the Oración en el Huerto and the Madonna de la Estrella.

Monday is all consecrated to one only congregation (cofradía), that of the Franciscan brothers. The "pasos" have their quarters at a very pretty Franciscan convent in downtown Lucena. Highlights this day are the "trono" (platform in which the sculptures are carried) of the venerated Medinaceli Christ, and the Virgen de Piedra, a Madonna like that of Michelangelo in the Vatican in Rome.

Tuesday sees 3 different congregations and 7 different "pasos" on the streets of Lucena. First one, the Carmine congregation, founded in 1606 with 3 very old, historical and peculiar "pasos" leaving from the Carmen church in Southern Lucena. Not to be missed the "Virgen de los Dolores", of the old school of Granada sculptures, as well as the "Señor de la Humildad". This congregation is one of the oldest in the city and have kept the same traditions as they were centuries ago.

The two other congregations have their site in the very central St. Matthew's Cathedral, in Plaza Nueva. The Servitas congregation, founded in 1724 but most important, the "Peace & Love" congregation, starring the "Madonna of Peace & Love", one of the most beautiful, balanced and prettiest "pasos" all week as well as the "Christ of Peace & Love". Tuesday is really worth a visit.

Wednesday is currently the poorest day in Lucena. Only one congregation, that of "El Valle", and 2 "pasos" only on the streets. But this refers only until midnight arrives and "Jueves Santo" begins, the most complete and traditional day in Lucena.

Thursday at midnight at St. Matthew's Cathedral takes place one of the most awaited moments of all week: the "Cristo del Silencio" comes out from church in silence and with all lights shut down. A very special moment that builds the closest link between the Andalusian Holy Week tradition and that of Castilian background. The "Cristo del Silencio" is the closest experience to a Castilian procession you can have in Lucena. But this is just the start. In the early afternoon, the second congregations starts its procession from the very small "Dios Padre" chapel in Eastern Lucena. 3 very peculiar "pasos" compose this congregation, 2 of which are unique to Lucena: that of the "Holy Faith Allegory" and also that of "Jesus washing St Peter's feet".

And now we come to the most awaited moment in the whole Easter Week tradition of Lucena. The most venerated and traditional "paso" is about to start its procession: the "Cristo de la Columna", by Pedro Roldán, comes out of St. Jacques church always punctual. The way this "paso" comes out, the way it is particularly carried, and all the "saetas" (flamenco-kind prayers that are sung as a virgin or christ is being processioned in Andalusia) that are sung during the whole evening-night are by themselves a reason to pay a visit to Lucena on that day. But this is not yet finished. The "Cristo de la Sangre", one of the most serious, traditional, respected and historical "paso" there is in Lucena. Coming out of the St. Francis church in downtown Lucena. In total, there are 9 "pasos" on Thursday in Lucena. And best of all, they all come together in Alcaide street Las Torres (downtown) where they head for Plaza Nueva (Main Square) before taking El Peso street, where they finally separate.

Thursday and Good Friday traditionally come together. There are just a few hours without "pasos" on the street since those of Thursday come back to church at 2:30 am and the next one, Nazareno Christ comes out at 6:00 am. Nazareno congregation is composed of 6 "pasos". The Nazareno itself is a very old and very much venerated sculpture of Renaissance style. The congregation was founded in 1599, one of the oldest in town. It has also kept the good old flavors of the past.

Saturday, there is only one congregation and one paso with it. The "Soledad". This congregation is the oldest one in Lucena, formed in 1564. Very pretty procession, well organized, balanced and serious.

Sunday, as usual, the "Resurrection" congregation puts an end to a whole week of celebrations.

See also

editNotable people

edit- Isaac ibn Ghiyyat (1038–1089)

- Joseph ibn Migash (Seville, 1077-1141), was a rabbi, posek and a rosh yeshiva who lived in Lucena most of his lifetime.

- Luis Ramírez de Lucena (1465-1530), a leading Spanish chess player, who wrote the oldest existing printed book on chess. The Lucena position is named after him.

- Luis Barahona de Soto (1548-1595), poet, a friend of Miguel de Cervantes.[24]

- Antonio Mohedano (1561-1625, Antequera), painter of the Renaissance period.[25][26]

- Francisco Hurtado Izquierdo (1699-1725, Priego de Córdoba), architect, author of the tabernacle in the Granada Charterhouse.[27]

- José María Hinojosa, "El Tempranillo" (1805-1833), bandolero.[28]

- Paco de Lucena (1859-1898), flamenco guitarist[29]

- Victor Perez (Director) (born 1981), Spanish director, producer and digital film compositor

References

edit- ^ Municipal Register of Spain 2018. National Statistics Institute.

- ^ a b Redes de Centros Históricos en Andalucía (PDF), Seville: Consejería de Obras Públicas y Transportes, 2002, ISBN 978-84-8095-293-4

- ^ Maíllo Salgado, Felipe (1993). "The City of Lucena in Arab Sources" (PDF). Mediterranean Historical Review. 8 (2): 149. doi:10.1080/09518969308569654.

- ^ Maíllo Salgado 1993, p. 149–151.

- ^ Botella Ortega, Daniel; Casanovas Miró, Jordi (2009). "El cementerio judío de Lucena (Córdoba)". Miscelánea de Estudios Árabes y Hebraicos. Sección Hebreo. 58. Granada: Editorial Universidad de Granada: 15. doi:10.30827/meahhebreo.v58i0.65 (inactive 1 November 2024).

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ García Arévalo, Tania María; Cano Pérez, María José (2016). "Documentos de regulación legal judía de la Lucena del siglo XI". Cuadernos de Historia del Derecho. 23. Madrid: Ediciones Complutense. doi:10.5209/rev_CUHD.2016.v23.53067.

- ^ Lacave, José Luis (1985). "Judíos y juderías". Judíos en la España medieval (PDF). p. 6. ISBN 84-7679-016-3.

- ^ Cañas Pelayo, Marcos Rafael (2012). "El colectivo portugués en Lucena y Aguilar (Siglos XVI-XVII)" (PDF). In Pérez Álvarez, María José; Rubio Pérez, Laurenano M. (eds.). Campo y campesinos en la España Moderna. Culturas políticas y el mundo hispano. León: Fundación Española de Historia Moderna. p. 1436. ISBN 978-84-938044-2-8.

- ^ García Arévalo & Cano Pérez 2016, pp. 340–341.

- ^ Hinojosa Montalvo, José (2000). "Los judíos en la España medieval: de la tolerancia a la expulsión" (PDF). In Martínez San Pedro, Mª Desamparados (ed.). Los marginados en el mundo medieval y moderno : Almería, 5 a 7 de noviembre de 1998. Almería: Instituto de Estudios Almerienses. p. 34. ISBN 84-8108-206-6.

- ^ Torres Balbás, Leopoldo (1954), "Mozarabías y juderías de las ciudades hispanomusulmanas" (PDF), Al-Andalus, 19: 190, ISSN 0304-4335

- ^ Espinosa Villegas, Miguel Ángel (1997). "Ciudad medieval y barrio judío: reflexiones". Cuadernos de Arte de la Universidad de Granada. 28: 7. ISSN 0210-962X.

- ^ Peláez del Rosal, Jesús, ed. (1985). De Abrahán a Maimónides, Volumen 3. Los judíos en Córdoba. Córdoba: Ediciones El Almendro. p. 132. ISBN 978-84-86077-38-9.

- ^ Chamocho Cantudo, Miguel Ángel (2017). Los fueros de los reinos de Andalucía: de Fernando III a los Reyes Católicos. Madrid: Agencia Estatal Boletín Oficial del Estado. p. 30. ISBN 978-84-340-2414-4.

- ^ a b Chamocho Cantudo 2017, p. 30.

- ^ Valle Porras, José Manuel (2019). "Las armerías en el conflicto antiseñorial de Lucena (Córdoba), a finales de la Edad Moderna" (PDF). Emblemata: Revista aragonesa de emblemática (25). ISSN 1137-1056.

- ^ Cañas Pelayo 2012, p. 1436.

- ^ Soria Mesa 2019, p. 128.

- ^ Soria Mesa, Enrique (2019). "Judaizantes o marqueses. Los judeoconversos de Lucena (Córdoba) entrelos siglos XV y XVII. Una primera aproximación a su estudio". In Soria Mesa, Enrique; Díaz Rodríguez, Antonio J. (eds.). Los judeoconversos en el mundo ibérico. Córdoba: UCO Press. p. 129. ISBN 978-84-9927-450-8.

- ^ Soria Mesa 2019, p. 134.

- ^ Atienza López, Ángela (2008). Tiempos de conventos: una historia social de las fundaciones en la España moderna. Madrid: Marcial Pons Historia. p. 168. ISBN 978-84-96467-73-6.

- ^ Cañas Pelayo 2012, p. 1438.

- ^ Cañas Pelayo 2012, pp. 1439, 1442–1443.

- ^ Rodríguez Marín, Francisco (1903). Luis Barahona de Soto, estudio biografico, bibliografico y critico. Sucesores de Rivadeneyra.

- ^ "Antonio Mohedano". Instituto Andaluz de Patrimonio Histórico (in Spanish). Junta de Andalucía. Archived from the original on 8 June 2016. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ J. R. S. P. "Mohedano de la Gutierra, Antonio". Fundación de Amigos del Museo del Prado (in Spanish). Museo del Prado. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ Ruiz Cardador, Félix (7 July 2019). "Francisco Hurtado Izquierdo, el arquitecto lucentino que fundió luz y majestad en el barroco". ABC (in Spanish). Vocento. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ García, José María (28 October 2002). "Otra biografía sobre ´El Tempranillo´ asegura que éste nació en Lucena". Diario Córdoba (in Spanish). Grupo Zeta. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- ^ ""Paco de Lucena incorporó nuevas técnicas a la guitarra flamenca"". El Diario de Córdoba (in Spanish). Joly Digital. 11 March 2019. Archived from the original on 23 September 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Lucena". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 17 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 96.