Penkridge (/ˈpɛŋkrɪdʒ/ PENG-krij) is a village[2][3] and civil parish in South Staffordshire District in Staffordshire, England. It is to the south of Stafford, north of Wolverhampton, west of Cannock, east of Telford and south-east of Newport.

| Penkridge | |

|---|---|

| Village and civil parish | |

Clockwise from top: Penkridge Festival Garden, St Michael's and All Angels Church, Market Street, Lock and Viaduct | |

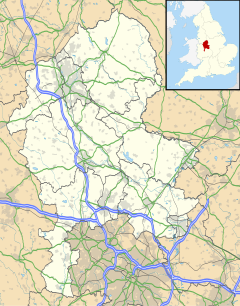

Location within Staffordshire | |

| Population | 8,526 (2011)[1] |

| OS grid reference | SJ922141 |

| District | |

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | STAFFORD |

| Postcode district | ST19 |

| Dialling code | 01785 |

| Police | Staffordshire |

| Fire | Staffordshire |

| Ambulance | West Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

The wealthiest establishment in Penkridge in the Middle Ages, its collegiate church building survived the abolition of the chantries and is the tallest structure in the village centre. The parish is crossed towards its eastern border by the M6 motorway and a separate junction north of the M6 toll between the West Midlands and Stoke-on-Trent. Penkridge has a railway station on the West Coast Main Line railway next to the Grade I listed medieval church. Penkridge Viaduct and the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal are to either side of Market Street and the Old Market Square and are among its landmarks.

Definition

editPenkridge is a parish unit within the East Cuttleston Hundred[4] of Staffordshire. Its boundaries have varied considerably over the centuries. The ancient parish of Penkridge, defined in 1551, although it existed in much the same form throughout the Middle Ages, was made up of four distinct townships: Penkridge itself, Coppenhall, Dunston, and Stretton. As a place with its own institutions of local government, the parish was also known as Penkridge Borough.[5]

Penkridge became a civil parish in the 1830s and in 1866 was shorn of the three smaller townships, which became separate parishes. It was constituted as a parish of four distinct constablewicks: Penkridge, Levedale, Pillaton, and Whiston. In 1934, the civil parish exchanged some territory with the surrounding parishes to rationalise the boundaries, acquiring the whole of the former civil parish of Kinvaston in the process. The civil parish was the merger of the following settlements or entirely farmed manors:

Location

editPenkridge is in the district of South Staffordshire in the county of Staffordshire. It is between Stafford, 5 miles (8 km) to the north and Wolverhampton, 10 miles (16 km) south, and lies mostly on the east bank of the River Penk.

The development of Penkridge has been closely linked to its relationship to major routes. The village of Penkridge lies on the medieval route between the county towns of Stafford and Worcester, which also passed through Wolverhampton. The Penkridge section became part of the major stagecoach routes linking London and Birmingham with Manchester and Liverpool and is now subsumed into the A449 road. Just to the south, at Gailey, this route crosses the historically still more important Watling Street, now the A5 road, which linked London to Chester, Wales, and ultimately Ireland. The village was also bisected by the Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal from 1770. Today Penkridge is grazed on its eastern side by the M6 motorway, the main route between London and the north-west of England and Glasgow.

Etymology

editThe popular etymology of the village's name derives it from the River Penk, which flows through it. It was assumed that since the village could be said to stand on a ridge by the Penk, it must derive its name from the river. However, this is to reverse the true derivation. The name of the village, or something like it, is attested many centuries before that of the river. The name "Penk" is actually a back-formation[7] from the name of the village.

The occupying Romans gave their fort in the area the Latin form Pennocrucium.[8] Cameron argues that this, like similar Latinized Celtic names, was passed by the native British directly, orally in its Celtic form, to the later Anglo-Saxon occupiers—not through the medium of Latin.[9] Thus the name Pennocrucium attests the origins of the name Penkridge, but is not its direct origin. In the indigenous Celtic, the name of the village was almost certainly penn-crug, meaning "the head (or end) of the ridge", or "chief hill or mound", and pronounced roughly penkrik. In very early times of Anglian settlement the inhabitants of the district were known as the Pencersæte. In 958, a charter uses the form Pencric for the settlement.[10] This is obviously close to the modern "Penkridge", and both are closer in pronunciation to the Celtic root than to the Latinized form.

The name might reflect the village's location at the terminus of the long ridge of land running along the east side of the river. However, this ridge is not actually very prominent and few visitors would perceive Penkridge as a hill town. Modern toponymists have become convinced that the hill in question was more likely a tumulus—prominent in pre-Roman and Roman times, and perhaps much later. Brewer comments that "none is evident in the locality".[7] However, Margaret Gelling, predisposed to find direct evidence for toponyms in the local landscape, has proposed a precise location for the mound, now destroyed by ploughing, that gave both the village and, ultimately, the river their names.[11] This was a tumulus at Rowley Hill Farm, Ordnance Survey reference GR90251180, approximately 52°42′18″N 2°08′46″W / 52.705°N 2.146°W, which was still prominent in the 18th century and still discernible in the early 20th. It would have directly overlooked the outlying Roman camp, across the Penk and just north of Pennocrucium on Watling Street, the remains of which are clearly visible in satellite photographs. Certainly, it makes more sense to look for the hill in question in the immediate vicinity of the ancient settlement than that of the modern village, which is well to the north of it. The Rowley Hill tumulus is well documented, and was clearly an extremely important landmark for several millennia.

Governance

editPenkridge is part of the Stone, Great Wyrley and Penkridge parliament constituency, currently represented by the Conservative Gavin Williamson. However, Penkridge area is a part of South Staffordshire district.

Penkridge is covered by a Non-metropolitan county two-tier system of local government:

- The District Council, which forms the lower tier, is South Staffordshire, based in Codsall. Penkridge is divided among three wards for elections to the district council: Penkridge North East and Acton Trussell; Penkridge West; Penkridge South East. Before the Local Government Act 1972 brought about the 1974 reform of local government in England and Wales, Penkridge was part of Cannock Rural District.

- The upper tier is the non-metropolitan county, colloquially shire county, of Staffordshire. Penkridge constitutes a single electoral division of the county.

All of Penkridge's councillors are currently Conservative.

History

editEarly settlement

editEarly occupation of the area around Penkridge has been confirmed by the presence of a Bronze or Iron Age barrow at nearby Rowley Hill.[12] A significant settlement in this vicinity has existed since pre-Roman times, with its original location being at the intersection of the River Penk and what became the Roman military road known as Watling Street (today's A5 trunk road). This would place it between Water Eaton and Gailey, about 2.25 miles (3.62 km) SSW of the village. The Roman settlement of Pennocrucium and earlier settlements were in the Penkridge area, but not on the same site as present village of Penkridge.

Medieval Penkridge

editAnglo-Saxon origins

editThe village of Penkridge dates back at least to the early Middle Ages, when the area was part of Mercia, although the foundation date is unknown. King Edgar in 958, described it as a "famous place",[13] so it was already of importance by then. In the Tudor period, it was claimed that the founder of the collegiate church of St. Michael at Penkridge was King Eadred (946-55), King Edgar's uncle,[14] which seems plausible.

The importance of the church

editPenkridge's church was of central importance to the village from Anglo-Saxon times and the Norman conquest did not change this. It was of a special status.

- It was a collegiate church: a church served by a community of priests, known as a chapter. The members were known as canons. They were not monks, but secular clergy. In 1086 the Domesday survey found that most of the farm land at Penkridge was held from the king by the nine priests of St. Michael's, who had six slaves and seven villeins working for them.

- It was a chapel royal – a place set aside by the monarchs for their own use – generally to pray and to offer mass for their souls. This made it completely independent of the local Bishop of Lichfield – an institution called a Royal Peculiar. In 1280 Penkridge even shut its doors on the Archbishop of Canterbury, when he tried to carry out a tour of inspection (known as a canonical visitation).

- It was organised like a cathedral chapter. This happened during the 12th century, probably during the Anarchy of Stephen's reign. The reorganised chapter was headed by a Dean. The other canons each received a particular estate to live off, called a prebend, and were known as prebendaries.

- It was headed by the Archbishop of Dublin from 1226. This was because in 1215 King John gave to Archbishop Henry of London, one of his most trusted administrators, the right to appoint the dean of Penkridge. He made himself dean on the next vacancy, and subsequent archbishops of Dublin automatically became deans of Penkridge.[15]

The collegiate church was the most important local institution for most of Penkridge's history: economically powerful and architecturally dominant. All the people of the parish had to be buried there, at considerable cost, so it was where the local magnates installed their memorials. Its area of jurisdiction defined Penkridge parish, which was also the main unit of local government until late Victorian times.

The dean and many of the canons were absentees, so they appointed vicars to act for them locally. The focus of worship was prayer and masses on behalf of the dead, not care for the living. Two priests were employed solely to serve in chantries for the monarch and for the Virgin Mary. By the 16th century, the people of Penkridge themselves subscribed to pay a morrow priest to celebrate a daily mass, so that they could worship. Pastoral care and preaching were not taken seriously until the 16th century or later.

- The Church of St. Michael and All Angels

-

Exterior view of the western end of the church, showing large Perpendicular window.

-

View of the tower, modified in late Perpendicular style in the 16th century.

-

East window. Perpendicular in style, it formerly contained much more tracery.

-

The wrought iron chancel gates of Dutch origin, dated 1778. The organ, formerly in the tower arch, was moved to present position in 1881.

-

Lavabo in wall of south chancel aisle

-

Stone pulpit, 1890, part of a substantial restoration and refurbishment which began in 1881.

-

The early 16th century tomb alcove of Richard Littleton and Alice Wynnesbury in the south nave aisle, now used for votive candles. Originally this part of the church was a Littleton family chapel.

The grip of the forest

editLarge areas surrounding Penkridge were placed by the Norman kings under Forest Law, a savage penal code designed to protect the ecology and wildlife for the king's enjoyment. These areas were part of the Royal Forest of Cank or Cannock Chase and were known as Gailey Hay and Teddesley Hay. Forest law kept most of south Staffordshire in an economic straitjacket. Conflicts between the barons and kings in the 13th century forced a relaxation, starting with the first issue of the Forest Charter in 1217. So it was in Henry III's reign that Penkridge began to grow economically and probably in population. Local people began to create new fields, called assarts, by clearing the trees and scrub (still a capital crime), and Penkridge acquired an annual fair and weekly market.[16]

Manors and magnates

editMedieval Penkridge was organised on the manorial system. There were a number of manors within the parish, of varying size and importance, each with its own lord, who owed feudal service to his own overlord, but exercised authority over his tenants. A list of the different medieval manors and estates would include:[17] Penkridge Manor, Penkridge deanery manor, Congreve, Congreve Prebendal Manor, Drayton, Gailey, Levedale, Longridge, Lyne Hill or Linhull, Mitton, La More (later Moor Hall), Otherton, Pillaton, Preston, Rodbaston, Water Eaton, Whiston, Coppenhall or Copehale, Dunston, and Stretton. The largest was the manor of Penkridge itself. King John's gift of 1215 to the Archbishop of Dublin included Penkridge manor. The Archbishop decided to divide it, giving about two-thirds to his nephew, Andrew de Blund, and keeping the rest for the deanery. The manor of Penkridge was passed on through the Blund (later called Blount) family and later other families of lay landlords.

The Church had large holdings of land. St. Michael's college had not only the deanery manor but also Preston and the Prebendal Manor of Congreve. The other prebends also held lands, but not as lords of the manor. Some manors belonged to Staffordshire monasteries. Burton Abbey held Pillaton, Bickford and Whiston, and also, for a time, Gailey, which later passed to the nuns of Black Ladies Priory at Brewood. Drayton belonged to the Augustinian Priory of St. Thomas, near Stafford.

Most of the manors were quite small and often their owners were fairly minor, although some small manors formed part of the wider holdings of great families. Even the most minor of lords had the right to hold manorial courts and to discipline their tenants, but a wealthy and important lord was like a monarch in his own manor. By the late 14th century the lords of Penkridge manor had obtained charters giving them rights to pursue criminals wherever they wished; to inflict the death penalty; to force tenants to take collective responsibility for offenders; and to confiscate stray livestock.

Just before 1500, the Littleton family make their first appearance in Penkridge. Richard Littleton brought Pillaton into the family's possession through marriage and Pillaton Hall was the Littleton family seat for about 250 years, the centre of an expanding property empire. Soon they took on the leases of most of St. Michael's church lands and established a family chapel in the church[18] – a statement of their growing importance. They were the most important local representatives of the landed gentry, a class that was to dominate rural life for several centuries.

Agriculture

editMuch of the Penkridge area was cultivated under the open field system, although the actual field names are not documented until 16th and 17th centuries, as they were about to be enclosed. In Penkridge manor, for example, there were Clay Field, Prince Field, Manstonshill, Mill Field, Wood Field, and Lowtherne or Lantern Field, Fyland, Old Field, and Whotcroft, and also common grazing areas, Stretton Meadow and Hay Meadow.[16] There are no detailed records of what was grown in medieval Penkridge. In 1801, when the first record was made, nearly half was under wheat, with barley, oats, peas, beans, and brassicas the other major crops – probably similar to the medieval pattern: farmers grew wheat wherever the land in their scattered strips supported it, and other crops elsewhere, with cattle on the riverside meadows and sheep on the heath.

The early medieval cultivators were mainly unfree, forced to work on the lord's demesne in return for their strips in the open fields. From the 14th century wage labour replaced the feudal labour system. By the 16th century, most landowners were renting or leasing most of their land and paying cash for labour to cultivate what remained. In 1535, for example, the manor of Drayton was worth £9 4s. 8d. annually, and the lion's share, £5 18s. 2d., came from money rents.[17]

Fairs, markets and mills

editFairs and markets were a vital part of the medieval economy, but a royal charter was needed for either, so they were highly profitable to the manors which had the right to hold them. The grant of Penkridge manor to the archbishop of Dublin included the right to hold an annual fair. This right was upheld for the Blund family by Edward I in 1278 and by Edward II in 1312.[19] The date varied, but in the Middle Ages it fell around the end of September and lasted for seven or eight days. It began as a general fair but developed into a horse fair by the late 16th century.

Henry III granted Andrew le Blund a weekly market in 1244. This was challenged by the burgesses of Stafford, who feared competition, but Penkridge kept its Tuesday market for centuries. After 1500 the market declined, expired and was revived several times, also changing days several times. The market place, still so-named but no longer used, was at the opposite end of the village from the church. The modern market is held on the livestock auction site close to Bull Bridge.

Mills were another great source of profit to lords of the manor, who forced their tenants to use them. The River Penk and a number of tributary brooks were able to drive mills. The Domesday Book of 1086 records mills at Penkridge at Water Eaton. A century later there were two mills at Penkridge and one of them was operated by the More family for centuries, as tenants of the dean. A mill is recorded at Drayton by 1194; at Congreve, Pillaton, and Rodbaston in the 13th century; at Whiston in the 14th; and at Mitton in the 15th. These were all corn mills, but in 1345 Water Eaton had a fulling mill, as well as the corn mill.[20]

Reformation and revolution: Penkridge in Tudor and Stuart Times

editDissolution

editThe Reformation brought major changes to landownership and social life at Penkridge. First came the Dissolution of the Monasteries under Henry VIII. This swept away Burton Abbey, and its manor of Drayton was sold in 1538 to the Bishop of Lichfield, who wanted it for his nephews. The College of St. Michael was not threatened at first, as it was not a monastery, but Edward VI's reign brought a more radical phase of the Reformation. In 1547 the Abolition of Chantries Act decreed the end of the chantry churches and their colleges. St. Michael's was still a thriving institution: a major rebuilding was in progress. Its estates enriched the dean (Archbishop of Dublin), seven prebendaries, two chantry canons, an official principal, three vicars choral, three further vicars, a high deacon, a subdeacon, and a sacrist. In 1547 its property was assessed at £82 6s. 8d. annually.[15] All this was swept away in 1548 and the first Vicar of Penkridge, Thomas Bolt of Stafford, was appointed on £16 per annum, with an assistant on £8.[21]

The Dudley inheritance

editPenkridge now became enmeshed in the meteoric career of John Dudley, Earl of Warwick, a key figure in Edward VI's regency council. In 1539, Dudley got control of Penkridge manor by foreclosing on a debt its owners, the Willoughby de Broke family, had owed to his father, Edmund Dudley. Next he grabbed the Deanery Manor and Tedesley Hay, making him the most important landowner in the area, although day-to-day management of the deanery lands stayed with the Littletons, the lessees. Dudley went on to seize almost absolute power in England, and taking the title Duke of Northumberland. Edward's early death in 1553 left Dudley high and dry. Edward's older sister, the Catholic Mary, succeeded but Dudley attempted a coup d'état in favour of Lady Jane Grey. Mary prevailed and Dudley was arrested and beheaded as a traitor. His lands were forfeit to the Crown, the extensive estates at Penkridge among them.

Dudley had the foresight to grant various estates to his relatives. So his daughter-in-law, Anne Dudley, Countess of Warwick, was able to keep a lifetime interest in Penkridge, while his wife hung on to Teddesley Hay until her death. Teddesley was bought by Sir Edward Littleton in 1555. A new Sir Edward succeeded in 1558 and his vigorous enclosure policy soon stirred up controversy. Penkridge manor entered into a limbo, prolonged by Anne's insanity. The fate of the deanery manor too was unresolved: it was taken from the Dudleys, but not restored to the Church, as Mary did not re-establish the chantries. So both remained with the Crown for a generation, with no decision on their fate. Not until the 1580s were matters resolved. In 1581 the college property was sold to speculators and in 1585 it was snapped up by Sir Edward Littleton. In 1582, Queen Elizabeth promised Penkridge manor to Sir Fulke Greville, heir to the Willoughby de Brokes, and he took over 1590.

Civil war

editThe Grevilles were powerful regionally and nationally. The Fulke Greville who inherited Penkridge in 1606 was a poet and statesman. He served both Elizabeth and James I, who gave him Warwick Castle as a seat and elevated him to the peerage as the 1st Baron Brooke. In 1628 he was murdered by a servant. As he was unmarried and childless, he had adopted his younger cousin Robert as his son and heir to both the title and the great estates in Staffordshire and Warwickshire. Robert was a leading parliamentarian and a Puritan, who promoted emigration to America. When the English Civil War broke out, he took command of a parliamentary army in central England and was killed during the siege of Lichfield Cathedral in 1643. He was succeeded by Francis Greville, 3rd Baron Brooke.

The Littletons were purely local landowners and instinctively loyalist. Sir Edward Littleton was made a Baronet by Charles I on 28 June 1627 and was expelled from the House of Commons in 1644 for his royalist sympathies. In May 1645, royalist troops quartered in Penkridge were expelled by small parliamentary force after a brief skirmish. Littleton's estates were sequestrated but he was able to recover them on payment of £1347. The Littletons' holdings were thus preserved and they found themselves in favour again after the restoration of Charles II in 1660. Despite the revolutionary turmoil, the real situation in Penkridge was little changed.

An anomaly surviving from before the Reformation was the peculiar jurisdiction of St. Michael's. Although the college was long gone, its privileges survived and were vested in the Littletons, owners of the deanery manor. They appointed vicars and kept bishops at bay, until the royal peculiar was ended in 1858.[15]

Changing fortunes: Georgian and Victorian Penkridge

editEconomy and population

editIn 1666, the township of Penkridge had 212 households and the rest of the parish about a hundred,[22] giving a total population of perhaps 1200 to 1500. By the first census, in 1801, it was 2,275.[23] It rose to a peak of 3316 in 1851. A fall thereafter is mainly the result of the parish being reduced in size by the loss of Coppenhall, Stretton and Dunston. Penkridge itself seems to have had a fairly stable population for the century from 1851 to 1951: a decline relative to the country as a whole, but not a collapse.

From the 1660s the pace of enclosure quickened, with all of the manors being divided into small farms, usually with the cultivators' consent, and these aggregated gradually into larger units. The second half of the 19th century, and especially the last quarter, were hard times for agriculture, with the repeal of the Corn Laws in 1846 and the Long Depression from about 1873. The 1831 census found that farmers and agricultural labourers accounted about 60% of the total adult male workforce.[24] Next came shop keepers and artisans, showing that Penkridge remained a small but important commercial centre, although the market had gone.[19] In 1881 agriculture employed about 48% of the working men: a considerable drop. Of the women whose employment is known, 150, the vast majority, were in domestic service.[25] – probably mainly with the local gentry. The hospitality industry was quite important, with 40 men working in food and lodging and 15 working with carriages and horses – reflecting the continuing importance of the inns on a major route. The diversity of trades is marked. No less than 43 – 25 women and 18 men – were involved in dress-making, and there were quarrymen, traders, and many others. However, professionals are numbered at only 14.

Penkridge owed much to its transport links, which steadily improved. The main Stafford–Wolverhampton route, now the A449 road was turnpiked under an Act of 1760. Bull Bridge, carrying the road over the Penk, was rebuilt in 1796 and widened in 1822. The improved road attracted more traffic: by 1818 there were stops by coaches on the London – Manchester, Birmingham – Manchester and Birmingham – Liverpool routes. The Staffordshire and Worcestershire Canal, opened in 1772, running straight through the parish and the township from north to south, with wharves at Spread Eagle (later called Gailey) and at Penkridge. In 1837, the Grand Junction Railway was opened. It cut through Penkridge on its west side, where Penkridge station was built, and was carried over the River Penk by the large Penkridge Viaduct. It began with two trains daily in each direction, to Stafford and Wolverhampton.

Heavy industry expanded in the 18th century, when a forge at Congreve was turning out 120 tons of iron a year, and in the 1820s the mill below Bull Bridge was used for rolling iron. However, this industry tailed off as the Black Country ironworks outstripped it. Extraction of building materials grew in Victorian times, with the Littletons operating quarries at Wolgarston, Wood Bank, and Quarry Heath,[22] as well as a sand pit at Hungry Hill, Teddesley, and a brickyard in Penkridge.[26]

Zenith of the Littletons

editThe fortunes of the village and the Littletons remained intertwined. Sir Edward Littleton, the fourth baronet, bought Penkridge manor from the Earl of Warwick in 1749, completing his family's dominance of the area. Soon after he built Teddesley Hall, a much more impressive seat for the family.[27] He survived until 1812, although, his wife died childless in 1781. He adopted his great-nephew, Edward Walhouse, as his heir. Walhouse took the name Littleton and took over the Littleton estates, although not the Littleton baronetcy. He achieved far greater eminence as a politician than any other member of the family, serving as Chief Secretary for Ireland under the Whig Prime Minister Grey in 1833–35. He was elevated to the peerage as Baron Hatherton, a title which remains with the head of the Littleton family to the present, and became an active member of the House of Lords.

Hatherton resided at Teddesley, where he established a free agricultural college and farmed 1,700 acres (688 ha) successfully. He strongly promoted education in the area, paying for a National School in Penkridge and another at Levedale, and for clothing for some of the school children. However, his lifetime saw a decisive shift in the family's interests. As heir to both the Walhouse family fortune and the Littleton estates, he owned great estates around Penkridge and mineral holdings and much residential property in the Cannock and Walsall areas. He owned coal mines at Great Wyrley, Bloxwich and Walsall; limestone quarries and brickyards in Walsall that were used to build much of the town; hundreds of residential and commercial properties; gravel and sand pits, stone quarries in many places. Unlike Penkridge, Cannock and Walsall were boom towns of the Victorian era, powered by the most modern and profitable industries of the age. The Littletons played a leading part in this phase of the Industrial Revolution and made large profits from it, and this tilted their attention increasingly away from their landed estates.

The modern village

editPenkridge in the 20th and 21st centuries has remained a thriving market village while evolving into a residential centre, but its ties to the land were weakened and those to the landed gentry broken. Residential development began even in Victorian times, with the middle-class villas of the St. Michael's Road area, close to the railway.[28] The main Stafford-Wolverhampton road was greatly improved between the wars, reshaping both Penkridge and Gailey.

The war itself prepared the way for changes. Teddesley Hall, no longer the Littleton's family home since 1930, was used to house troops and prisoners of war. The old common lands between the Penk and the Cannock Road were used as a military camp during the war years. This eased their subsequent development as a large housing estate, greatly enlarging the size and population of Penkridge in the 1950s and 1960s. Between 1951 and 1961 the population grew from 2,518 to 3,383 – a rise of over 34% in just ten years.[23]

In 1919, the 3rd Lord Hatherton had begun disinvestment in land, often selling farms to their tenants. Over 2,000 acres (8 km2) went in the Penkridge area, including land in the Deanery Manor, Congreve, Lower Drayton, Upper Drayton, Gailey, Levedale and Longridge.[29] In 1953 the 4th Lord Hatherton sold off nearly 4,000 acres (16 km2), including Teddesley Hall, which was demolished within a year.[27]

The M6 motorway came around Stafford in 1962 and connected with the M1 motorway in 1971.

The only large stores are the Co-operative supermarket. Independent shops, cafés, inns and services occupy the area between the old market place to the east and Stone Cross on the A449 to the west. The area between Pinfold Lane and the river, long the site of livestock sales, has emerged as a new market place, attracting large numbers of visitors to Penkridge on Wednesdays and Saturdays.

Facilities

editPenkridge's local market has been revived and is held on Wednesdays and Saturdays, hosting up to 100 stalls. There is also an antiques market every Thursday. The substantial tower of the Grade I listed Church of St. Michael and All Angels on the western edge of the village, parts of which date back to the early thirteenth century, is visible even to passing road and rail travellers. A smaller Methodist church is on the largest road (the A449) route through the village, and there are three short streets of buildings dating from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, from the railway station eastward. Penkridge has its own historical stocks and cells remain in the village centre.

The village has several pubs, and there are also numerous sports clubs in Penkridge including cricket, football, rugby union and tennis clubs.

On the last Friday in November, for one night, the village centre used to close to traffic to allow a Victorian Night and Christmas Market to take place, in 2010 this event moved to the Market site where it has expanded to include over 70 stalls and a funfair.

Notable people

edit- Sir Edward Littleton, 1st Baronet (c.1599 – c.1657) a 17th-century[30] English Baronet and politician from the extended Lyttelton family

- Richard Hurd (1720–1808) was an English divine[31] and writer, and Bishop of Worcester

- Alethea Lewis (1749–1827) was an English novelist, she also used the pseudonym Eugenia de Acton. Her subject-matter centred on her profound Christianity.

- Sir Lovelace Stamer (1829-1908) was the first Anglican Bishop of Shrewsbury in the modern era. He died in retirement at Penkridge.[32]

- Ernest J. Chambers (1862–1925) was a Canadian militia officer,[33] journalist, author, and civil servant. Emigrated aged 8.

- George Edalji (1876 in Penkridge – 1953) a Parsi English solicitor[34] who served three years' hard labour after being convicted on a charge of injuring a pony. He was pardoned after a campaign well supported by Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

- Rebekah Staton (born 1981) is an English actress,[35] best known for narrating Don't Tell The Bride and appearing as Della in Raised by Wolves

- Adam Legzdins (born 1986 in Penkridge) is an English professional footballer[36] and goalkeeper, made over 150 professional appearances so far, played for Birmingham City F.C. 2015-2017

Transport

editPenkridge lies on the A449 and is midway between junctions 12 and 13 of the M6 motorway. It is served by National Express long-distance coaches, by Chaserider service 75 (Cannock-Stafford) and also by occasional services provided by Select Bus from Wolverhampton to Stafford on service 878. As from April 2021, service 75 will be replaced by Select Bus service 875 six days per week. The previous hourly Arriva Midlands service 76 was withdrawn in 2019 due to competition from National Express West Midlands service 54, which was itself withdrawn in 2020.

Penkridge is served by Penkridge railway station on the West Coast Main Line, and can also be accessed by the Staffordshire & Worcestershire Canal. Otherton Airfield is in Penkridge, it is the home of Staffordshire Aero club.

Twin towns

editSince 1986, Penkridge has been twinned with Ablon-sur-Seine in France.[37][38]

See also

editReferences

edit- ^ "ONS Neighbourhood Statistics Penkridge". Retrieved 30 October 2014.

- ^ "Penkridge Parish Council | Penkridge, Staffordshire". Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ "Penkridge Market - Permanent Market in Penkridge, Penkridge". Enjoy Staffordshire. Retrieved 11 October 2024.

- ^ White, William (1851) History, Gazetteer and Directory of Staffordshire

- ^ Penkridge Borough at A Vision of Britain Through Time.

- ^ Victoria County History: Staffordshire: Volume 5, East Cuttlestone Hundred, 16, Penkridge – Introduction and manors.

- ^ a b Ayto, John & Crofton, Ian (2005) Brewer's Britain and Ireland. London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson ISBN 0-304-35385-X, p. 864.

- ^ Itinerarium Antonini Augusti et Hierosolymitarum, ediderunt G. Parthey et M. Pinder. Berlin (Berolini: Impensis Friderici Nicolai), 1848 (Iter Britannarium, Iter II, "Pennocrucio")

- ^ Cameron, Kenneth (1996) English Place Names. London: Batsford ISBN 0-7134-7378-9, p.33.

- ^ The Electronic Sawyer: Online Catalogue of Anglo-Saxon Charters, S667

- ^ Gelling, Margaret (1984) Place-Names in the Landscape. London: J. M. Dent ISBN 0-460-86086-0, p. 138

- ^ Victoria County History of Staffordshire, pp.192-3, 376

- ^ The Electronic Sawyer: Online Catalogue of Anglo-Saxon Charters, S667 Edgar says he is in loco famoso qui dicitur Pencric.

- ^ Victoria County History: Staffordshire: Volume 3, 34: The College of St. Michael, Penkridge.

- ^ a b c VCH: Staffordshire: Volume 3: 34

- ^ a b VCH Staffordshire: Volume 5:17 – Penkridge: Economic history, s.2. Agriculture

- ^ a b VCH: Staffordshire: Volume 5:16.s.2. Manors

- ^ VCH:Staffordshire: Volume 5:17.s.5 Churches

- ^ a b VCH Staffordshire:Volume 5:17 – Penkridge: Economic history, s.4.

- ^ VCH Staffordshire: Volume 5:17 – Penkridge: Economic history, s.2. Mills

- ^ VCH Staffordshire: Volume 5:17 – Penkridge: Economic history, s.5. Churches

- ^ a b VCH: Staffordshire: Volume 5:16.s.1.

- ^ a b Penkridge: Total Population at A Vision of Britain Through time

- ^ Penkridge 1831 Occupational Categories at A Vision of Britain through Time, transcribed by David Allan Gatley (School of Social Sciences, University of Staffordshire).

- ^ Penkridge 1881 Occupational Orders at A Vision of Britain through Time, edited by Matthew Woollard (History Data Service, UK Data Archive, University of Essex).

- ^ The National Archives, Estate D260/M/E

- ^ a b VCH Staffordshire: Volume 5: 23: s.2: The Hay

- ^ VCH: Staffordshire: Volume 5:16.s.1.

- ^ VCH: Staffordshire: Volume 5:16.s.2 – Manors

- ^ The History of Parliament Trust, LITTLETON, Sir Edward I (c.1548-1610) retrieved December 2017

- ^ . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 13 (11th ed.). 1911.

- ^ 'Deaths', "The Times", Tuesday, 3 November 1908, p.11

- ^ Dictionary of Canadian Biography, Volume XV (1921–1930) CHAMBERS, ERNEST JOHN retrieved December 2017

- ^ The Plebeian website, Conan Doyle and the Parson’s son: The George Edalji Case retrieved December 2017

- ^ IMDb Database retrieved December 2017

- ^ SoccerBase Database retrieved December 2017

- ^ Penkridge Parish Council website retrieved 10 January 2019

- ^ "British towns twinned with French towns". Archant Community Media Ltd. Retrieved 11 July 2013.