Axis (anatomy)

| Axis | |

|---|---|

Position of axis (shown in red). | |

Second cervical vertebra, or epistropheus, from above. | |

| Details | |

| Identifiers | |

| Latin | Axis, vertebra cervicalis II |

| MeSH | D001368 |

| TA98 | A02.2.02.201 |

| TA2 | 1050 |

| FMA | 12520 |

| Anatomical terms of bone | |

In anatomy, the axis (from Latin axis, "axle") or epistropheus, is the second cervical vertebra (C2) of the spine, immediately posterior to the atlas, upon which the head rests.

The pivot joint between the atlas and axis is the atlanto-occipital joint, which allows the head to nod up and down on the vertebral column.

The axis' defining feature is its strong odontoid process (bony protrusion) known as the dens, which rises dorsally from the rest of the bone. In some judicial hangings, the odontoid process may break and hit the medulla oblongata, causing death.[citation needed]

Structure

The body is deeper in front or in the back and is prolonged downward anteriorly to overlap the upper and front part of the third vertebra.

It presents a median longitudinal ridge in front, separating two lateral depressions for the attachment of the longus colli muscles.

Dens

The dens, also called the odontoid process or the peg, are the most pronounced projecting feature of the axis. The dens exhibit a slight constriction where it joins the main body of the vertebra. The condition where the dens are separated from the body of the axis is called os odontoideum and may cause nerve and circulation compression syndrome.[1] On its anterior surface is an oval or nearly circular facet for articulation with that on the anterior arch of the atlas. On the back of the neck, and frequently extending on to its lateral surfaces, is a shallow groove for the transverse atlantal ligament which retains the process in position. The apex is pointed and gives attachment to the apical odontoid ligament. Below the apex, the process is somewhat enlarged and presents on either side a rough impression for the attachment of the alar ligament; these ligaments connect the process to the occipital bone.

The internal structure of the odontoid process is more compact than that of the body. The odontoid peg is the ascension of the atlas fused to the ascension of the axis. The peg has an articular facet at its front and forms part of a joint with the anterior arch of the atlas. It is a non-weight bearing joint. The alar ligaments, together with the apical ligaments, are attached from the sloping upper edge of the odontoid peg to the margins of the foramen magnum. The inner ligaments limit rotation of the head and are very strong. The weak apical ligament lies in front of the upper longitudinal bone of the cruciform ligament and joins the apex of the deltoid peg to the anterior margin of the foramen magnum. It is the fibrous remnant of the notochord.

Other features

The pedicles are broad and strong, especially in the front, where they coalesce with the sides of the body and the root of the odontoid process. They are covered above by the superior articular surfaces.

The laminae are thick and strong. They play a large role in the stability of the cervical spine alongside the laminae of C7.[2]

The vertebral foramen is large, but smaller than the atlas.

The transverse processes are very small, and each ends in a single tubercle. Each process is perforated by the transverse foramen, which is directed obliquely upward and laterally.

The superior articular surfaces are round, slightly convex, directed upward and laterally, and are supported on the body, pedicles, and transverse processes.

The inferior articular surfaces have the same direction as those of the other cervical vertebrae.

The superior vertebral notches are very shallow, and lie behind the articular processes. The inferior vertebral notches lie in front of the articular processes, as in the other cervical vertebrae.

The spinous process is large, very strong, deeply channelled on its under surface, and presents a bifurcated extremity.

Variation

Contact sports are contraindicated for individuals with anomalous dens, as any violent impact may result in a catastrophic injury.[3] This is because a malformed odontoid process may lead to instability between the atlas and axis (the C1 and C2 cervical vertebrae).

Development

The axis is ossified from five primary and two secondary centres.

The body and vertebral arch are ossified in the same manner as the corresponding parts in the other vertebrae, viz., one centre for the body, and two for the vertebral arch.

The centres for the arch appear about the seventh or eighth week of fetal life, while the centres for the body appear in about the fourth or fifth month.

The dens, or odontoid process, consist originally of a continuation upward of the cartilaginous mass, in which the lower part of the body is formed.

During about the sixth month of fetal life, two centres make their appearance in the base of this process: they are placed laterally, and join before birth to form a conical bilobed mass deeply cleft above; the interval between the sides of the cleft and the summit of the process is formed by a wedge-shaped piece of cartilage.

The base of the process is separated from the body by a cartilaginous disk, which gradually becomes ossified at its circumference, but remains cartilaginous in its center until advanced age.

In this cartilage, rudiments of the lower epiphyseal lamella of the atlas and the upper epiphyseal lamella of the axis may sometimes be found.

The apex of the odontoid process has a separate centre that appears in the second and joins about the twelfth year; this is the upper epiphyseal lamella of the atlas.

In addition to these, there is a secondary centre for a thin epiphyseal plate on the undersurface of the body of the bone.

Clinical significance

Fracture of dens

Fractures of the dens, not to be confused with Hangman's fractures, are classified into three categories according to the Anderson Alonso system:

- Type I Fracture - Extends through the tip of the dens. This type is usually stable.

- Type II Fracture - Extends through the base of the dens. It is the most commonly encountered fracture for this region of the axis. This type is unstable and has a high rate of non-union.

- Type III Fracture - Extends through the vertebral body of the axis. This type can be stable or unstable and may require surgery.[1]

-

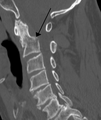

A fracture of the base of the dens as seen on plain X ray

-

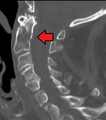

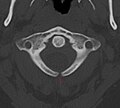

A fracture of the base of the dens as seen on CT

-

Type 3 odontoid fracture

-

Type 2 dens fracture

Additional images

-

Its shape and position (shown in red) from above. The skull is shown in semi-transparent.

-

Axis seen from above.

-

3D image

-

Posterior atlantooccipital membrane and atlantoaxial ligament. (Axis visible at center.)

-

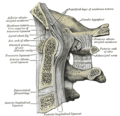

Median sagittal section through the occipital bone and first three cervical vertebræ.

-

Sagittal section of nose mouth, pharynx, and larynx.

-

Axis on x-ray

-

Unfused arch of atlas at CT.

See also

References

![]() This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 99 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

This article incorporates text in the public domain from page 99 of the 20th edition of Gray's Anatomy (1918)

- ^ Jumah, Fareed; Alkhdour, Saja; Mansour, Shaden; He, Puhan; Hroub, Ali; Adeeb, Nimer; Hanif, Rimal; Mortazavi, Martin M; Tubbs, R. Shane; Nanda, Anil. "Os Odontoideum: A Comprehensive Clinical and Surgical Review". Cureus. 9 (8). doi:10.7759/cureus.1551. ISSN 2168-8184. PMC 5630463. PMID 29018648.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Pal, G. P.; Routal, R. V. (April 1996). "The role of the vertebral laminae in the stability of the cervical spine". Journal of Anatomy. 188 ( Pt 2): 485–489. ISSN 0021-8782. PMC 1167584. PMID 8621347.

- ^ Schenck, Robert C., ed. (1999). Athletic Training and Sports Medicine (3 ed.). American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. ISBN 9780892031726.

External links

- Netter, Frank. Atlas of Human Anatomy, "High Cervical Spine: C1-C2"

- Axis - Blue Link Anatomy - University of Michigan Medical School

- auctions