Comitium

Archaeological drawing of the excavations of the Comitium in 1899. This is the current level exposed today. | |

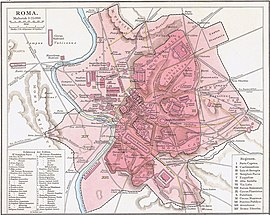

Click on the map for a fullscreen view | |

| Location | Regione VIII Forum Romanum |

|---|---|

| Coordinates | 41°53′34″N 12°29′6″E / 41.89278°N 12.48500°E |

| Type | Forum (Roman) |

| History | |

| Builder | Tullus Hostilius/Julius Caesar |

| Founded | 7-4th century BC |

The Comitium (Italian: Comizio) was the original open-air public meeting space of Ancient Rome, and had major religious and prophetic significance.[1] The name comes from the Latin word for "assembly".[2] The Comitium location at the northwest corner of the Roman Forum was later[vague] lost in the city's growth and development, but was rediscovered and excavated by archaeologists at the turn of the twentieth century.[citation needed] Some of Rome's earliest monuments, including the speaking platform known as the Rostra, the Columna Maenia, the Graecostasis, and the Tabula Valeria, were part of or associated with the Comitium.

The Comitium was the location for much of the political and judicial activity of Rome.[when?] It was the meeting place of the Curiate Assembly, the earliest Popular assembly of organised voting divisions of the Republic.[3] Later, during the Roman Republic, the Tribal Assembly and Plebeian Assembly met there. The Comitium was in front of the meeting house of the Roman Senate – the still-existing Curia Julia and its predecessor, the Curia Hostilia. The Curia Julia is associated with the Comitium by both Livy and Cicero.[4]

Most Roman cities had a similar Comitium for public meetings (L. contiones) or assemblies for election, councils and tribunals.[5] As part of the forum, where temples, commerce, judicial, and city buildings were located, the Comitium was the center of political activity. Romans tended to organize their needs into specific locations within the city. As the city grew, the larger Comitia Centuriata met on the Campus Martius, outside the city walls. The Comitium remained of importance for formal elections of some magistrates; however, as their importance decayed after the end of the republic, so did the importance of the Comitium.[6]

Archaic history

[edit]The earliest use of the Comitium as a political assembly area, along with the beginnings of Rome itself, is blurred between legend and archaeological discovery. The traditional stories of King Servius Tullius and Romulus have many similarities regarding the origins of the comitia, leading Romulus to be often interpreted as a copy of Tullius. Both were closely related to the God Vulcan, played a role in organizing the comitia, and were depicted as founders of Rome.[7] Other conflicting, or "duel" mythologies include the supposed tomb of Romulus, who was struck and killed during the Sabine conflict and was buried under the Vulcanal. Alternative legends state that he was only wounded and that spot was where Faustulus was killed separating the twins during combat. Many of the legends themselves transferred to the Comitum from the Palatine. For example, the pomeriam where Remus is said to have slept as well as the Ficus Ruminalis and the sculpture of the she-wolf suckling the twins have competing legends.[8] The original Palatine settlement, Roma quadrata, contained the relics of Romulus. An extension of the square city is seen in the "Septimontium", the original seven hills.[9] Ancient stories suggest that Tarpeia was drawing water from a spring here when she saw Tatius for the first time.[10]

The Comitium contains the earliest surviving document of the Roman State, a cippus or inscribed pedestal found on the second floor of the Comitium, and dated to 450 BC. This inscription informs citizens of their civic duties.[11] Roman tribunals were held in the Comitium before other alternative locations became acceptable. Eventually such trials would be moved to the basilicas or the forum, except for more elaborate affairs.[12] The Comitium had a number or temporary wooden structures that could be taken down during the flood season. Court would generally consist of a magistrate, the condemned (generally kept in a cage below the elevated platform), representation for the condemned, and the prosecutor. The Rostra Vetera was a permanent tribunal eventually made into a war monument but still within the Comitium templum. The Rostra itself may have been considered a templum. A sundial that stood on the Rostra for a period of time was eventually replaced with newer devices.[1] The site has been used for capital punishment, as well as to display the bodies and limbs of defeated political opponents and funerals. Both the forum and Comitium had been used for public exhibitions.[12]

In his 1912 study, Francis Macdonald Cornford explains that the Roman Comitium was inaugurated as a temple, shaped like a square and oriented to the four corners of the sky. But Plutarch describes a circular site traced by Romulus at the founding of Rome using divination, after he had sent for men of Etruria who taught him the necessary sacred rites. A circular trench was cut into the ground and votive offerings and samples of earth from each man's native lands were placed within. "The ditch is called mundus- the same name given firmament (Ολυμπος)." From the center of this circle, the circuit of the city wall was designated and plowed. Everything within this area was sacred. It was the traditional center of the city as a similar area was in the original Palatine settlement.[13] The Umbilicus urbis Romae marks the center of Rome.[14] The senate council probably began meeting within an old Etruscan temple on the north side of the Comitium identified as belonging to the Curia Hostilia from the seventh century BC. Tradition holds that Tullus Hostilius built or refurbished this structure.[15] A royal complex may have existed near the House of the Vestal Virgins on one end of the Forum Romanum.[16]

Under the Roman Republic

[edit]When Rome became a republic, the original altar and Shrine of Vulcan may have served as a podium for senators or political opponents. Next to this spot is where the Rostra has its early beginnings. It is believed that the tradition of speaking to crowds from an elevated platform for political purposes may have begun as early as the first king of Rome.[17] In this area was another raised platform for speakers, with ascending and descending stairs on either side. The first structure to be called "Rostra" was on the south east section of the forecourt of the Curia Hostilia at the edge of the Comitium. As the population grew, not all Romans could fit in the Comitium, and speakers in the later Republic would turn their backs on the Curia and crowds within the Comitium and direct their speech to the crowd in the forum.[18] All of the city's most important decisions and laws were made in the senate. A law required that any bill not approved within an inaugurated and consecrated space was not valid. For this reason all meeting spaces of the senate were temples. Over time as the senate's size and power increased, so did the size of the senate house. In 80 BC the curia was enlarged by Sulla, who also added heating to the building for the first time.[19]

In 55 BC a political war broke out within the city between two factions, one led by Clodius, the other by his adversary Milo. The Rostra became a fortress and was more than once used to throw deadly missiles upon the opposing side. On January 2, 52 BC, Clodius died at the hands of the opponents near Bovillae, setting off a riot as his followers carried the body to the Comitium and cremated it on a funeral pyre improvised with the senatorial seating from the Curia Hostilia. The fire consumed the Curia, destroying it as well as damaging the Basilica Porcia. Faustus Sulla, son of the dictator Sulla, was commissioned by the senate to rebuild the Curia. His structure lasted only seven years until Julius Caesar replaced it with a building of his own design.[20]

Structures within the Comitium

[edit]The Comitium was open towards the forum. At the boundary were the monuments and statues recording political events and recognizing famous Romans.[21] There were four sacred fig trees in the city, three of which were within the forum. A tree planted near the Temple of Saturn was removed when its root system began undermining a valued statue. In the medio foro a fig tree stood aside an olive tree and a grape vine. Verrius Flaccus, Pliny and Tacitus state that a third tree stood in the Comitium near the statue of the augur Attus Navia who, legend says, split a wet stone with a razor in the Comitium and transferred the Ficus ruminalis or its sacred importance from the base of the Palatine hill to the assembly area.[22][23] Scholars still refer to the Ficus Navia as the Ficus Ruminalis while accepting the difference.[24] Livy reports that a statue to Publius Horatius Cocles was erected in the Comitium.[25] There existed another grandstand within the Comitium beside the Rostra. The Graecostasis was located on the northwest side of the forum.[26] Beside the Rostra and the Graecostasis was the Columna Maenia. In 338 BC, Consul Gaius Maenius erected a column that some historians believe to be from the atrium of his home which was sold to Cato and Flaccus[which?] as mentioned by Pseudo-Asconius (Caec. 50).[27] Pliny states that the accensus consulum announced the supremam horam, the time when the sun had moved downward from the Columna Maenia to the Carcer. This was done from the same location as the call for midday, the Curia. The column was south of the place of observation or on a line which passed from the Rostra and Graecostasis.[28] The Tabula Valeria was one of the first public works of its kind in the city. In 263 BC, Consul Manius Valerius Maximus Corvinus Messalla placed a painting of his victory over Heiro and the Carthaginians in Sicily, on the side of the ancient curia. Samuel Ball Platner states in his book, The topography and monuments of ancient Rome (1911):

A more probable explanation is that the Tabula Valeria was an inscription in bronze or marble, containing the provisions of the famous Valerio-Horatian laws concerning the office of tribune. Such a tablet might very naturally be set up near their subsellia."[29]

The Comitium changed after the time of Caesar. The original spot of many of the monuments and statues was altered drastically. One of the biggest changes was to the Rostra Vetera.[30][31] This structure changed considerably even before 44 BC. It began with the first curia for the senate in 600 BC and a shrine that was added 20 years later[32] where, it is said, miraculous events occurred of milk and blood raining down from the heavens.[33]

Under Julius Caesar

[edit]Caesar's rise to power as a military general along with his successful campaigns led to sharing of power within the Republic, known as the First Triumvirate. The shared power did not last and Caesar became dictator for life (and the last Roman dictator). The Comitium was reduced in size twice in consecutive order by Cornelius Sulla and again by Julius Caesar.[34] One of Caesar's many building projects was to remove or replace the Rostra Vetera, level the Comitium and dismantle the curia and realign it with the new Rostra.[35]

An episode that may have contributed to the Liberatores conspiracy against Caesar was on the occasion of the festival of the Lycea, or Lupercalia. Mark Antony, as one of the participants, approached Caesar while he stood in the Comitium on the Rostra. Antony ceremoniously attempted to place a laurel wreath on Caesar's head. Caesar theatrically refused, and received applause from the people. This was done several times until the wreath was finally placed upon the head of a statue of Caesar, which was then immediately torn down by Caesar's enemies.[36]

The Rostra was the most prestigious spot in Rome to speak from. Cicero remarked[where?] on the honor in his first speech during his term as praetor. It was the first time Cicero spoke from the Rostra.[37] The Philippics became one of the most popular writings of the orator. The works marked a return to active politics in 43 BC after a long retirement. In them,[citation needed] he attacked Mark Antony as the greatest threat to republican government after Caesar's death.[38] He wrote of the libertas or freedoms that the citizens of Rome had forfeited under Julius Caesar and violently denounced Mark Antony.[39] He made at least one of these epic speeches from the Rostra. When the conspirators had all been defeated, Augustus had tried but failed to keep Cicero's name off the death list. Eventually Antony wins and has the orator's head and hands displayed on the Rostra.[40]

Archaeology

[edit]The Comitium in Rome

[edit]During the Middle Ages artifacts from the ancient Roman civilization sparked curiosity with collectors.[vague] Early digging throughout Europe amounted to little more than destructive treasure hunting and grave robbing. Formal archaeology in Rome only began in the 19th century with the foundation of the Instituto di Corrispondenza and the work of Edward Gerhard. Starting with museums rather than excavation, archaeological work began by studying and cataloguing existing collections as background knowledge for the philological study of antiquity.[41]

A number of German archaeologists joined Gerhard to map out the city of Rome, the forum and the Comitium being of great importance as the topographical center.[42] He was joined by Chevalier Bunsen, Earnst Platner, Wilhelm Röstell, B. G. Niebuhr and Friedrich Hoffmann in writing the book Beschreibung der Stadt Rom in 1817, which was published in 1832.[43] The theories presented did not have full support from their peers. In his book, A dictionary of Greek and Roman geography published in 1854, Sir William Smith remarked:

The German views respecting the Capitol, the Comitium, and several other important points, have found many followers; but to the writer of the present article they appear for the most part not to be proved; and he has endeavoured in the preceding pages to give his reasons for that opinion.

No major excavation of the Comitium was undertaken until the turn of the century. Previous digs had only uncovered levels dated to the late empire. Such was the case in 1870, when later pavements or structures were located and digging was stopped by request for viewing and study and never resumed. In 1898, a committee was established to examine and study the earlier architectural fragments to establish an order for restoration of ancient buildings. The conclusion of this study was that new and more detailed excavations were required. That same year, G. Boni requested that the tramway in front of the church of Sant'Adriano al Foro be removed. His request was met in October and substantial new funds were made available for an extended excavation.[44] In December 1898, excavations began. Between 1899 and 1903 Boni and his collaborators discovered the Lapis Niger (the "Black Rock") as well as other artifacts while excavating the Comitium.[45] During the medieval period the Comitium had been converted into a Christian cemetery and part of the Curia made into a catacomb. Consequently, over 400 bodies were unearthed and moved during excavations.[46]

In the American Journal of Archaeology, second series, volume 4 1900, a letter from Samuel Ball Platner was published dated July 1, 1899. In the letter he stated:

In front of the Arch of Severus begins the line along which the main work of the past months has been done. The whole front wall of San Adriano, the Curia of Diocletian, and the Comitium are now in sight. The Comitium is paved with blocks of travertine and extends to and around the lapis niger, which, although on the same level, is protected on at least two sides by a sort of curb. This pavement of the Comitium extends out to a point directly opposite the middle of the Arch of Severus, and ends just beyond the lapis niger with a curved front wall, which is itself built over an older tufa pavement. Further back it also rests upon older structures. Part of the Comitium had evidently been built over at a late period in something the same way as the Basilica Aemilia.

The Comitia of other urban centers

[edit]In 1953 an American excavation at the Roman Latin colony of Cosa, 138 kilometres (86 mi) northwest of Rome, along the coast of Italy, in modern Tuscany, identified the remains of the city's Comitium and found rounded amphitheatre steps directly in front of the local senate house. The discovery prompted further excavations in Rome at the site of the Comitium in 1957.[47] Cosa was founded in 237 BC as a military outpost in the newly conquered territory of the Etruscans. The city's port and town features were laid out in the third century BC using regular town plans, with intersecting streets at right angles and forum and cult center on the arx.[48]

Commentary on the Comitium

[edit]Vitruvius' De architectura (ca. 30 BC) contains the following statement:

In Sparta, paintings have been taken out of certain walls by cutting through the bricks, then have been placed in wooden frames, and so brought to the Comitium to adorn the aedileship of [C. Visellius] Varro and [C. Licinius] Murena.[49]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b Vasaly, Ann (1993). Representations. University of California Press. pp. 61–64. ISBN 978-0-520-20178-1.

- ^ Definition of comitium

- ^ Willis, George (2005). The Roman assemblies from their origin to the end of the republic. Adamant Media Corporation. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-4021-3683-2.

- ^ Burn, Robert (January 1, 1871). Rome and the Campagna. Deighton, Bell, and Co.; First Edition. pp. 82.

- ^ Taylor, Lily Ross (February 15, 1991). Roman voting assemblies from the Hannibalic War to the dictatorship of Caesar. University of Michigan Press. pp. 21. ISBN 978-0-472-08125-7.

- ^ E. Burton-Brown (1905). Recent excavations in the Roman Forum, 1898–1905. Scribner's. pp. 81.

- ^ Grandazzi, Alexandre (November 1997). The foundation of Rome: myth and history. Cornell University Press. pp. 207. ISBN 978-0-8014-8247-2.

- ^ Pais, Cosenzahor, Ettorie, Emilio (1906). Ancient legends of Roman history. London, Swan Sonnenschein & Co., LTD. pp. 33.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ How, Leigh, Walter Wybergh, Henry Devenish (June 2, 2008). A history of Rome to the death of Caesar. Kessinger Publishing, LLC. pp. 37. ISBN 978-1-4365-7150-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Lanciani, Rodolfo Amedeo (1897). The ruins and excavations of ancient Rome. Houghton Mifflin. pp. 262.

- ^ Frier, Bruce W. (March 1, 1999). Libri annales pontificum maximorum. University of Michigan Press. pp. 127–128. ISBN 978-0-472-10915-9.

- ^ a b Nichols, Francis Morgan (1877). The Roman Forum: a topographical study. London. Longmans and Co. Rome. Spithover. pp. 146–149.

- ^ Cornford, Francis Macdonald (November 8, 1991). From religion to philosophy: a study in the origins of western speculation. Princeton University Press. pp. 53. ISBN 978-0-691-02076-1.

- ^ Italy. Soprintendenza archeologica di Roma, Adriano La Regina (2004). Archaeological guide to Rome: the Roman Forum, the Palatine, the Capitol and the Capitoline museums, the Imperial forums, the Coliseum, the Domus Aurea. Electa. ISBN 978-88-435-8366-9.

- ^ Cornell, Tim (October 5, 1995). The beginnings of Rome: Italy and Rome from the Bronze Age to the Punic Wars ... Routledge; 1 edition. pp. 126. ISBN 978-0-415-01596-7.

- ^ Watkin, David (2009). The Roman Forum. Harvard University Press. pp. 217. ISBN 978-0-674-03341-2.

- ^ Scullard, Howard Hayes (December 20, 2002). A History of the Roman World, 753 to 146 BC. Routledge; 5 edition. pp. 57. ISBN 978-0-415-30504-4.

- ^ Boëthius, Axel; rev. by Roger Ling and Tom Rasmussen (1978). Etruscan and Early Roman Architecture. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-056144-7.

- ^ Rosenstein, Morstein-Marx, Nathan Stewart, Robert (December 13, 2006). A companion to the Roman Republic. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 354. ISBN 978-1-4051-0217-9.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hülsen, Christian (1906). The Roman forvm. G.E. Stechert & Co; 2nd edition. p. 16. ASIN B00085VS26.

- ^ Boëthius, Axel (November 25, 1992). Etruscan and early Roman architecture. Yale University Press. pp. 112. ISBN 978-0-300-05290-9.

- ^ Alain M. Gowing (11 August 2005). Empire and Memory: The Representation of the Roman Republic in Imperial Culture. Cambridge University Press. pp. 134–. ISBN 978-1-139-44582-5. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ William Ramsay (1859). An Elementary Manual of Roman Antiquities. Griffin. pp. 8–. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Evans, Jane DeRose (September 1, 1992). The art of persuasion: political propaganda from Aeneas to Brutus. University of Michigan Press. pp. 75–78. ISBN 978-0-472-10282-2.

- ^ Livy, Ab urbe condita, 2.10

- ^ Christopher John Johanson (2008). Spectacle in the Forum: Visualizing the Roman Aristocratic Funeral of the Middle Republic. pp. 69–. ISBN 978-1-109-12079-0. Retrieved 18 March 2013.[permanent dead link]

- ^ Briscoe, John (February 25, 2008). A commentary on Livy, books 38-40. Oxford University Press, USA. pp. 366. ISBN 978-0-19-929051-2.

- ^ O'Connor, Charles James (September 1909). "The Graecostasis and its vicinity". Bulletin: Philology and Literature Series. 3: 188. Retrieved 2009-08-15.

- ^ Platner, Samuel Ball (1911). The topography and monuments of ancient Rome. Allyn and Bacon. pp. 232.

- ^ William Smith (1873). A dictionary of Greek and Roman geography. J. Murray. pp. 792–. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Geoffrey S. Sumi (2005). Ceremony And Power: Reforming Politics in Rome Between Republic And Empire. University of Michigan Press. pp. 51–. ISBN 978-0-472-11517-4. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Jorg Rupke (28 May 2012). Religion in Republican Rome: Rationalization and Ritual Change. University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 9–. ISBN 978-0-8122-0657-9. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Robert Burn (1876). Rome and the Campagna: An Historical and Topographical Description of the Site, Buildings, and Neighbourhood of Ancient Rome. Deighton, Bell. pp. 82–. Retrieved 18 March 2013.

- ^ Nicole Maser (2004-05-23). "Authority In Public Spaces" (PDF). Georgia Institute of Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2006-09-10. Retrieved 2007-02-28.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Sumi, Geoffrey (September 28, 2005). Ceremony and power: performing politics in Rome between Republic and Empire. University of Michigan Press; illustrated edition. pp. 78–80. ISBN 978-0-472-11517-4.

- ^ Plutarch, Scott-Kilvert, Plutarch, Ian (October 30, 1965). Makers of Rome, nine lives: Coriolanus, Fabius Maximus, Macellus, Cato the ... Penguin Classics. pp. 281–282. ISBN 978-0-14-044158-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Morstein-Marx, Robert (March 15, 2004). Mass oratory and political power in the late Roman Republic. Cambridge University Press. pp. 53. ISBN 978-0-521-82327-2.

- ^ Hubbard, Thomas K. (May 12, 2003). Homosexuality in Greece and Rome: a sourcebook of basic documents. University of California Press; 1 edition. pp. 341. ISBN 978-0-520-23430-7.

- ^ Skinner, Quentin (September 16, 2002). Visions of politics. Cambridge University Press. pp. 314. ISBN 978-0-521-58925-3.

- ^ Ballif, Moran, Michelle, Michael (March 30, 2005). Classical rhetorics and rhetoricians: critical studies and sources. Praeger Publishers. pp. 105. ISBN 978-0-313-32178-8.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Andrén, Anders (January 31, 1998). Between artifacts and texts. Springer; 1 edition. pp. 15. ISBN 978-0-306-45556-8.

- ^ Smith, Sir William (1854). A dictionary of Greek and Roman geography. Boston: Little Brown 1854. Complete two volume set. pp. 853.

- ^ Platner, Bunsen, Gerhard, Röstell, Urlichs, Niebuhr, Hoffmann, Ernest Zacharias, Christian Karl Josias, Eduard, Wilhelm, Ludwig von, Barthold Georg, Friedrich (January 1, 1832). Beschreibung der Stadt Rom. J. G. Cotta; Elibron Classics edition. ISBN 978-0-543-99903-0.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Wiseman, Timothy Peter (January 1, 1992). Talking to Virgile. University of Exeter Press; 1 edition. pp. 134. ISBN 978-0-85989-375-6.

- ^ Ashby, Thomas (January 1904). "THE RECENT EXCAVATIONS IN THE FORUM ROMANUM, 1898-1903". The Builder. LXXXVI: [2]. Retrieved 2009-08-13.

- ^ Hare, Augustus John Cuthbert (1905). Walks in Rome: (including Tivoli, Frascati, and Albano). LONDON: KEGAN PAUL, TRENCH, TRUBNER & CO. LTD. pp. 135.

- ^ MacKendrick, Paul (November 17, 1983). The Mute Stones Speak. W.W. Norton & Co.; Second Edition. pp. 98. ISBN 978-0-393-30119-9.

- ^ Collins-Clinton, Jacquelyn (August 1997). A late antique shrine of Liber Pater at Cosa. Brill Academic Pub. pp. [1]. ISBN 978-90-04-05232-1.

- ^ Vitruvius Pollio, The Ten Books on Architecture or De Architectura, Harvard University Press (1914) Bk.2, Ch.8, Sec.9, p.53

Bibliography

[edit]Andrén, Anders (1998). Between Artifacts and Texts. New York: Plenum Press. ISBN 978-0-306-45556-8.

Ballif, Michelle (2005). Classical Rhetorics and Rhetoricians. New York: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-313-32178-8.

Boëthius, Axel (1978). Etruscan and Early Roman Architecture. New York: Penguin Books. ISBN 0-14-056144-7.

Botsford, George (2005). The Roman Assemblies from Their Origin to the End of the Republic. City: Adamant Media Corporation. ISBN 978-1-4021-3683-2. (originally published in 1909)

Collins-Clinton, Jacquelyn (1997). A Late Antique Shrine of Liber Pater at Cosa. City: Brill Academic Pub. ISBN 978-90-04-05232-1.

Cornell, Tim (1995). The Beginnings of Rome. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-01596-7.

Cornford, Francis (1991). From Religion to Philosophy. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02076-1.

Evans, Jane (1992). The Art of Persuasion. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-10282-2.

Frier, Bruce (1999). Libri Annales Pontificum Maximorum. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-10915-9.

Grandazzi, Alexandre (1997). The Foundation of Rome. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-8247-2.

Hubbard, Thomas (2003). Homosexuality in Greece and Rome. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-23430-7.

MacKendrick, Paul (1983). The Mute Stones Speak. New York: Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-30119-9. (first ed. 1960; second edition issued to claim copyright)

Morstein-Marx, Robert (2004). Mass Oratory and Political Power in the Late Roman Republic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-82327-2.

Richardson, Lawrence Jr. (1992). A new topographical dictionary of ancient Rome. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 978-0-801-84300-6.

Rosenstein, Nathan (2006). A Companion to the Roman Republic. City: Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-0217-9.

Scott-Kilvert, Ian (1981). Makers of Rome. Harmondsworth Eng.: Penguin. ISBN 978-0-14-044158-1.

Scullard, H. (2003). A History of the Roman World, 753-146 B.C. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30504-4. (Since the 4th ed., 1980, issues have only been reprints)

Skinner, Quentin (2002). Visions of Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-58925-3.

Sumi, Geoffrey (2005). Ceremony and Power. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-11517-4.

Taylor, Lily (1991). Roman Voting Assemblies: from the Hannibalic War to the Dictatorship of Caesar. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 978-0-472-08125-7. (These Jerome Lectures were published in 1966; the date 1991 only refers to the paperback edition)

Vasaly, Ann (1996). Representations. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20178-1.

Other authors referenced

[edit]These books are out of print and have no ISBN. Their age means some information in the books or journals may have changed or newer theories advanced since the original publication. They are used in this article where information is either the earliest, the original, or the very first works printed on the subject, or where information is still pertinent today.

Brown, E. Burton- (1905). Recent excavations in the Roman Forum. Scribner's.

Burn, Robert (1871). Rome and the Campagna. Deighton, Bell, and Co.

Hülsen, Christian (1906). The Roman forvm. G.E. Stechert & Co.

Lanciani, Rodolfo Amedeo (1897). The ruins and excavations of ancient Rome. Houghton Mifflin.

O'Connor, Charles James (1909). The Graecostasis and its vicinity. University of Wisconsin.

Pais, Cosenzahor, Ettorie, Emilio (1906). Ancient legends of Roman history. London: Swan Sonnenschein & Co., LTD.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Platner, Bunsen, Gerhard, Röstell, Urlichs, Niebuhr, Hoffmann, Ernest Zacharias, Christian Karl Josias, Eduard, Wilhelm, Ludwig von, Barthold Georg, Friedrich (January 1, 1832). Beschreibung der Stadt Rom. . G. Cotta; Elibron Classics edition.{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

Platner, Samuel Ball (1911). The topography and monuments of ancient Rome. Allyn and Bacon.

Smith, Sir William (1854). dictionary of Greek and Roman geography. Boston: Little Brown.

External links

[edit]- Digital Roman Forum: Resource: Comitium UCLA

- Prof. Giacomo Boni: The Roman Forum & the Antiquarium Forense - Rediscovery and the Restoration (2009–10), the Comitium Excavations (2009–10).

- Lucentini, M. (31 December 2012). The Rome Guide: Step by Step through History's Greatest City. Interlink. ISBN 9781623710088.

![]() Media related to Comitium at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Comitium at Wikimedia Commons

| Preceded by Basilica Ulpia |

Landmarks of Rome Comitium |

Succeeded by Curia Julia |