Georges Bégué

Georges Bégué | |

|---|---|

| |

| Nickname(s) | Bombproof |

| Born | 22 November 1911 Périgueux, France |

| Died | 18 December 1993 Falls Church, Virginia, U.S. |

| Allegiance | France/United Kingdom/United States |

| Service | Special Operations Executive, |

| Years of service | 1940–1945 |

| Unit | Autogiro |

Georges Pierre André Bégué[1][2][3] (22 November 1911 – 18 December 1993),[4] code named Bombproof, was a French engineer and agent of the United Kingdom's clandestine organization, the Special Operations Executive (SOE). The purpose of SOE in France, occupied by Nazi Germany in World War II, was to conduct espionage, sabotage, and reconnaissance. SOE agents allied themselves with French Resistance groups and supplied them with weapons and equipment parachuted in from England.

Bégué was the first of 470 SOE F (France) Section agents infiltrated into France. He was a wireless operator. He proposed the use of BBC to transmit coded messages to resistance groups in Europe, a practice which became ubiquitous. He also arranged for the first of many thousands of airdrops of supplies and arms to resistance groups in France. He was captured by the French police in October 1941. He escaped from prison in 1942 and returned to the United Kingdom.

Early life

[edit]Georges Bégué was born 22 November 1911 in Périgueux, France. His father was a railway engineer and the family moved to Egypt when Bégué was a child. Bégué also trained as an engineer at University of Hull where he learned English and met his wife. He went through his military service as a signaller.[5]

World War II

[edit]At the outbreak of World War II, Bégué was recalled to the French army. Because of his knowledge of English he was assigned to liaison with the British troops. He eventually escaped to Britain during the Dunkirk evacuation. After the surrender of France, he joined the Royal Signals as a sergeant, meeting Thomas Cadett, the Paris correspondent of the BBC, who was working in SOE's F section who recruited him.[6]

The first SOE agent

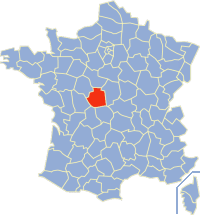

[edit]In 1940 SOE Bégué joined the new F (French) section. He was given the alias George Noble and trained as a wireless operator. After training, he parachuted "blind" (nobody met him on arrival) into Indre Department on the night of 5/6 May 1941 with a heavy wireless transmitter in a suitcase. He was the first SOE agent in France. He was lucky to have arrived at all, as the night before his flight the house he was staying in had been destroyed by a bomb while he was out.[7] He contacted socialist Max Hymans near Châteauroux and persuaded him that he was a legitimate English agent. Hymans introduced him to other socialists in the area. On 9 May, he sent his first wireless message back to SOE headquarters in London. On 10/11 May, he was joined by SOE agent Pierre de Vomécourt and on 12/13 May by Roger Cottin, both also parachuted blind.[8][9]

The Germans quickly detected Bégué's wireless transmissions and jammed them and began to hunt for him around Châteauroux. Nevertheless, he was able to arrange the first airdrop of supplies into France by SOE on 13 June 1941. Two containers were dropped at Bas Soleil, the estate of Pierre de Vomécourt's brother, Philippe, near Limoges. The containers were dropped by an Armstrong Whitworth Whitley bomber and contained sub-machine guns, explosives, and other material. They were the first of nearly 60,000 containers of supplies and arms air-dropped to SOE operatives and resistance groups during World War II.[10]

Bégué and Pierre de Vomécourt created the first of about 90 SOE networks (also called circuits and reseau) in France. Their network was called Autogiro.[11] Georges Bégué is sometimes called "Georges One" as he was the first SOE wireless operator in France. Subsequent wireless operators were called "Georges Two, Georges Three, etc. The SOE's slang term for a wireless operator was a "pianist."[12]

Engaging the BBC

[edit]Bégué had an exhausting schedule, often transmitting and receiving messages to and from SOE three times a day. In addition he often had to serve as a courier traveling by train to deliver or receive messages to other SOE agents. As the Germans and French police were attempting to locate him and his wireless through direction-finding equipment, Bégué proposed sending seemingly obscure personal messages to agents in the field in order to reduce risky radio traffic. In accordance with his proposal, the BBC's Radio Londres broadcasts began with "Please listen to some personal messages," followed by spoken messages, often amusing, and without context. Representative messages include "Jean has a long mustache" and "There is a fire at the insurance agency," each one having some meaning to a certain resistance group.[13] They were used primarily to provide messages to the resistance, but also to thank SOE agents and sometimes to mislead the enemy. Because these messages were in code, not cipher, the German occupiers could not hope to decipher them unless they had infiltrated a resistance group, so they focused their efforts on jamming the messages instead. The transmission of coded messages by Radio Londres became ubiquitous in World War II.[14]

Arrest

[edit]The SOE parachuted in a number of additional agents in September 1941. One agent, Gerry Morel, went his own way to recruit resistance members. The Milice, the Vichy France police, arrested him at Limoges on 3 October 1941. His arrest led to more arrests and eventually to Bégué, who was arrested 24 October in a Marseilles safe house. He was sent to join a dozen SOE agents in the Beleyme prison in Périgueux. They were later transferred to a prison camp in Mauzac-et-Grand-Castang, Dordogne in March 1942, thanks to intervention of the American Consul-General Hugh Fullerton. Bégué smuggled out a message to London, bribed a guard, and created a duplicate key and the group escaped 16 July 1942.[15] SOE agent Michael Trotobas was one of the escapees as was Jean-Pierre Bloch, whose wife, Gabrielle Sadourny, assisted in the escape.[16]

Bégué and the other escapees hid in a forest while the French police searched for them and then continued to Lyon in separate groups. Bégué arrived on 23 July. SOE agent, American Virginia Hall, was in Lyon and in contact with the Vic escape network and eventually the escapees were led over the Pyrenees to neutral Spain where Bégué was interned at Figueres and sent to Miranda de Ebro prison camp but was later released to continue to England. He arrived in London in October 1942.[15][17]

The SOE in London had changed leadership in his absence and Bégué had little confidence in the new SOE leader, Maurice Buckmaster. He was named signals officer, but believed his talents were under-utilized.[15]

After the war

[edit]After the war Bégué emigrated to the United States. He worked in a number of lower-level jobs until he could officially become an electronics engineer. He also became an American citizen.[15] He died 18 December 1993 in Falls Church, Virginia. He was 82 years old.[4] Begues was survived by his wife Rosemary and two daughters, Brigitte and Suzanne.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "Catalogue description Georges Pierre André BÉGUÉ, aka George Robert NOBLE, aka Georges Robert MERCIER, aka I".

- ^ Daily Telegraph news campx.ca

- ^ "Wanborough Manor - School for Secret Agents". Archived from the original on 13 November 2017. Retrieved 12 April 2018.

- ^ a b Social Security Death Index "Social Security Death Index Interactive Search". Archived from the original on 20 August 2008. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- ^ "Georges Begue," The Times (London), 2 February 1994.

- ^ The Times.

- ^ Tickell, Jerrard (1960), Moon Squadron, Hodder and Stoughton, pp. 30-32

- ^ Foot, M.R.D. (1966), SOE in France, London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office, pp. 161-164

- ^ Cookridge, E.H. (1967), Set Europe Ablaze, New York: Thomas Y. Crowell Company, pp. 67-68

- ^ Foot, pp. 163-164

- ^ Foot, pp. 145-146

- ^ Vomécourt, Philippe de (2016), An Army of Amateurs, Pickle Publishing, Kindle Edition, Location 432

- ^ Tillman, Barrett (5 November 2018). Brassey's D-Day Encyclopedia: The Normandy Invasion A-Z. Brassey's. ISBN 9781574887600.

- ^ Cookridge, pp. 55-56

- ^ a b c d e The Times,

- ^ Foot, p 203

- ^ Foot, p. 161.

External links

[edit]- People from Périgueux

- 1911 births

- 1993 deaths

- French Special Operations Executive personnel

- British Army personnel of World War II

- French military personnel of World War II

- Royal Corps of Signals soldiers

- Recipients of the Military Cross

- 20th-century French engineers

- French emigrants to the United States

- Alumni of the University of Hull

- Operation Overlord