Hôtel d'Assézat

This article needs additional citations for verification. (July 2024) |

The Hôtel d'Assézat in Toulouse, France, is a French Renaissance hôtel particulier (individual mansion) of the 16th century which houses the Bemberg Foundation, a major art gallery of the city.

The hôtel was likely built by Toulouse architect Nicolas Bachelier for Pierre d'Assézat, an internationally renowned Toulouse woad merchant at the time. As one of the first manifestations of French classicism it is an outstanding example of Renaissance palaces architecture of southern France, with a use of brick typical of Toulouse and an elaborate decoration of the cour d'honneur (courtyard) influenced by Italian Mannerism and by classicism.

The Hôtel d'Assézat differs from the other Renaissance townhouses in Toulouse not only in size and its exceptional ornamentation, but also in its pristine condition, a fact which earns it a mention in every overview of French Renaissance. The hôtel now belongs to the City of Toulouse and was restored in the 1980s. It is home to the Union des sociétés savantes, the Académie des Jeux Floraux and the Bemberg Foundation.[1]

History

[edit]Pierre Assézat was at the height of his social and professional success when he launched the construction of his mansion close to the Merchant Exchange, of which he had been one of the founders. Nevertheless, he did get caught up in the religious troubles of the time. A Calvinist convert, he was obliged to leave Toulouse after attempting to seize the town along with his fellows capitouls in 1562. He recanted ten years later and returned to his townhouse in Toulouse where he died in 1581.[1]

The house seems to have been mostly completed as early as 1562, as all the components visible today were already there at that date.[2]

The house was sold on August 20, 1761 to Nicolas-Joseph Marcassus de Puymaurin, who modified the mullioned windows but without disfiguring the hotel. He also commissioned the Louis XVI style decoration of one of the salons. At the time of the sale, he was moderator and president of the Royal Academy of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture of Toulouse. Twenty years later, the hotel became the property of the Sabatier family, then, in 1816, of the Gèze family.

Théodore Ozenne, who bought this building in 1894, bequeathed it to the city upon his death so that it could host learned societies,[3] including the oldest literary society in Europe. It is still one of his vocations today. From 1980, the city began the restoration of old buildings as well as the construction of a modern extension.

Presentation

[edit]Assézat launched the first phase of construction in 1555–1557. The two classical facades of the courtyard were built by the architect Nicolas Bachelier and by the stonemason Jean Castagnié. On the deaths of Castagnié and Bachelier the construction work stopped; it was restarted in 1560, under the direction of Dominique Bachelier, son of Nicolas. He undertook the creation of the loggia and the passageway, which divided up the courtyard, and the street gate. Much polychrome interplay (brick/stone) and various ornaments (cabochons, diamonds, masks) evoke luxury, surprise and abundance, themes peculiar to mannerist architecture.[1]

-

The courtyard.

-

The hôtel as seen from the street.

Classical facades

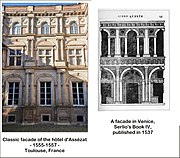

[edit]The main L-shaped structure was built along with the staircase pavilion in the corner. The design of the façades, featuring twin columns which develop regularly over three floors (Doric, Ionic, Corinthian), takes its inspiration from the great classical models such as the Coliseum. The careful treatment of the capitals systematically uses the most sophisticated antique expression known. The Doric on the ground floor is, for example, through Serlio or Labacco, an allusion to its most ornate known version: that of the Basilica Aemilia.[1][4]

This composition of the facades of the hotel bears no direct resemblance to that of the Lescot facade of the square courtyard of the Louvre Palace, to which it is sometimes compared.[2]

- Classical facades

-

Classical facades.

-

Superimposition of the three classical orders.

-

Influence of an engraving by Serlio.

-

Fluted and filleted columns.

-

Doric capitals.

-

Influence of Serlio's engravings

-

Ionic capitals.

-

Corinthian capitals.

-

Entrance of the Union of Academies and Learned societies.

-

It was the door of the counter.

-

Detail.

-

Window.

-

Window.

-

Serlian window.

-

Lion muzzle serving as a gargoyle.

Main gate

[edit]The monumental gate designed by Dominique Bachelier combines power with delicacy. The gateway arch takes a certain rhythm from several projecting stones decorated with small dots. Serlio's Extraordinary Book of Doors contain this type of composition and it was used on several occasions by Toulousain architects (Hôtel de Molinier and Hôtel de Massas). The Doric pilasters that frame the gate display an alternating succession of diamond-shaped stone, which gives the ensemble a precious aspect. In the upper section the Ionic pilasters around the mullioned window are fluted and delicately ornamented. And with the table that surmounts it, the composition imparts a refined sophistication. Thus, Dominique Bachelier was able to offer the owner a complete composition which evoked both power and a delicate erudition.[1]

- Entrance pavilion

-

Entrance pavilion.

-

Main gate.

-

Influence of an engraving by Serlio.

-

Frieze of metopes.

-

Detail.

-

An Amerindian's head, the attraction of novelty.

-

Merchant's office window on the street.

-

Merchant's office window on the courtyard.

-

Knocker of the door.

The passageway and the loggia

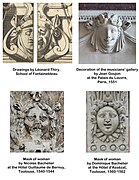

[edit]In the courtyard, the passageway features arches decorated with diamond-shaped stone. They rest on large scrolled consoles, whose fronts are decorated with grotesque masks of different design. On the side, the rolls of the scrolls engender plant pods and cloves. Each console is borne upon a lion foot standing on a section of pilaster capped underneath with a magnificent rose. These consoles illustrate, by themselves, the manneristic aesthetic on the unusual and the association of opposites, combining mineral, vegetable and animal kingdoms. These refined motifs, heightened through the polychrome interplay and relief of the passageway, were much appreciated by contemporaries and inspired details on other buildings, such as Hôtel de Massas and Laréole Castle.[1]

The loggia, the upper floor of which corresponds to a 17th century elevation (except for the 16th century windows, which used to stand out on a high slate roof), is at that time independent of the left wing and is located above the semi-buried cellars. A porch with converging flights of stairs provides access to it. A sort of festive tribune from which the lively courtyard can be observed, it brought pleasure to outdoor life in the summer months.[2]

- Passageway and loggia

-

Passageway of the east wall.

-

Support arch of the passageway.

-

Mannerist decor.

-

Mannerist decor.

-

Mannerist decor.

-

A variety of sources of inspiration.

-

Ionic consoles and pods.

-

Loggia.

-

Loggia.

-

Loggia.

The staircase and the tower

[edit]The large staircase with straight handrails takes place in a pavilion that projects into the courtyard. The architectural orders are repeated on the landings. On the landing of the first floor, stands the impressive figure of a male term. Half man, half pilaster, his face grimacing and his hands holding a cushion placed on his head to reduce the pain, this term was condemned to support the weight of the console. Although a symbol of knowledge in the sense that it alludes to mythology (Atlas and Hercules), this motif also amuses thanks to an association of opposites, such as the straining muscles and the soft cushion. Cariatid termes and other telamons were much appreciated in Renaissance Toulouse, notable examples can be found on the windows of Hôtel du Vieux-Raisin and on the main gate of Hôtel de Bagis.[1]

The brick crowning of the tower makes it the highest of the town's mansions. Probably finished by Dominique Bachelier, who gave it the shape of an Italian tempietto, it has two terraces and a parapet walk.[2]

- Staircase and tower

-

The tower.

-

The top of the tower.

-

The top of the tower.

-

Door of the main staircase.

-

Solomonic columns.

-

The staircase.

-

Staircase term.

-

Mannerist decor.

Bemberg Foundation

[edit]

Since 1994, the Hôtel d'Assézat has housed the Bemberg Foundation (Fondation Bemberg), an art gallery which presents to the public one of the major private collections of art in Europe: the personal collection of the wealthy Argentine Georges Bemberg (1915–2011). His foundation was created in collaboration with the City of Toulouse. The large Bemberg collection features paintings, drawings, sculptures, ancient books and furniture. Paintings and drawings are the highlights of the collection, especially 19th, and early 20th century French paintings (with Impressionism, Nabis, Post-Impressionism and Fauvism) and Venetian paintings of the 16th and 18th centuries.

The painting and drawing collection includes an impressive set of 30 paintings by Pierre Bonnard and 18th century Venetian paintings by Canaletto, Francesco Guardi, Pietro Longhi, Rosalba Carriera, Giovanni Paolo Pannini, Tiepolo. 18th century French painting is represented by François Boucher, Nicolas Lancret, Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun and Hubert Robert.

From the Flemish and Netherlandish schools of painting are artworks by the studio of Rogier van der Weyden, Lucas Cranach, Gerard David, Adriaen Isenbrandt, Joachim Patinir, Pieter Brueghel the Younger, Frans Pourbus the Elder. For the 17th century paintings are displayed by Antoon van Dyck, Pieter de Hooch, Nicolaes Maes, Jan van Goyen, Philips Wouwerman, Isaac van Ostade.

Italian Renaissance painting is centered on Venice with paintings by Paris Bordone, Jacopo Bassano, Titian, Paul Veronese and Tintoretto while for the 17th century, there are works by Pietro Paolini, Giovanni Battista Carlone, Evaristo Baschenis, Mattia Preti.

French Renaissance and 17th century painting are represented with Jean Clouet, François Clouet, Nicolas Tournier while the Foundation bought in 2018, a canvas by Spanish painter Francisco de Zurbarán.

French painting from the second half of the 19th century is well represented with paintings by Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Eugène Boudin, Claude Monet, Henri Fantin-Latour, Edgar Degas, Édouard Vuillard, Odilon Redon, Paul Sérusier, Paul Gauguin, Louis Valtat, Alfred Sisley, Camille Pissarro, Gustave Caillebotte, Berthe Morisot, Paul Signac and Paul Cézanne.

20th century French art is represented by Georges Rouault, André Derain, Henri Matisse, Raoul Dufy, Albert Marquet, Maurice de Vlaminck, Kees van Dongen, Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Othon Friesz, Amedeo Modigliani and Maurice Utrillo.

- Bemberg foundation

-

Anthony van Dyck, Portrait of Dorothy, Lady Dacre

-

Le clocher de Saint-Tropez by Paul Signac (1896)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Explanatory comments of Toulouse Renaissance exhibition (2018), Colin Debuiche.

- ^ a b c d Book l'hôtel d'Assézat, under the direction of Louis Peyrusse and Bruno Tollon. Publisher: l'Association des amis de l'Hôtel d'Assézat (2002).

- ^ "Baron Edmond de Rivières, « Chronique : L'hôtel d'Assézat à Toulouse », dans Bulletin monumental, 1895, tome 70, p. 258-259".

- ^ Collective work directed by Pascal Julien, «catalogue de l'exposition Toulouse Renaissance» ("Toulouse Renaissance exhibition catalogue"), Somogy éditions d'art, 2018.

Bibliography

[edit]- Bruno Tollon, Hôtels de Toulouse, p. 313–318, in Congrès archéologique de France. 154e session. Monuments en Toulousain et Comminges. 1996, Société française d'archéologie, Paris, 2002

- Marcel Sendrail, Pierre de Gorsse, Robert Mesuret, L'Hôtel d'Assézat, Édouard Privat éditeur, Toulouse, 1961

- Guy Ahlsell de Toulza, Louis Peyrusse, Bruno Tollon, Hôtels et Demeures de Toulouse et du Midi Toulousain, Daniel Briand éditeur, Drémil Lafage, 1997

- Louis Peyrusse, Bruno Tollon, Jacques Gloriès, L'hôtel d'Assézat. Publisher: l'Association des amis de l'Hôtel d'Assézat, Toulouse, 2002.

External links

[edit]- Houses completed in the 16th century

- Buildings and structures in Toulouse

- Art museums and galleries in France

- Museums in Toulouse

- Art museums and galleries established in 1994

- Renaissance architecture in Toulouse

- Renaissance architecture in France

- Hôtels particuliers in Toulouse

- 1994 establishments in France