Saimbeyli

Saimbeyli

Hadjin • Հաճն | |

|---|---|

District and municipality | |

Partial view of the town | |

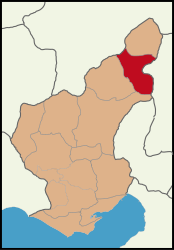

Map showing Saimbeyli District in Adana Province | |

| Coordinates: 37°59′N 36°05′E / 37.983°N 36.083°E | |

| Country | Turkey |

| Province | Adana |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Mahmut Dal (AKP) |

Area | 989 km2 (382 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 1,050 m (3,440 ft) |

| Population (2022)[1] | 13,621 |

| • Density | 14/km2 (36/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+3 (TRT) |

| Postal code | 01740 |

| Area code | 0322 |

| Website | www |

Saimbeyli, historically known as Hadjin (Armenian: Հաճըն, romanized: Hačən), is a town and district of Adana Province in present-day Turkey.[2] Its area is 989 km2,[3] and its population is 13,621 (2022).[1] The town is located at the Taurus mountains of Cilicia region, 157 km north of the city of Adana.

Saimbeyli is perched in a valley between the forested mountains of Dibek and Bakir. There is a pass through the mountains from here to Kayseri and the valley is watered by mountain streams.

It was one of the sites of the 1909 Adana massacres during the Armenian genocide.

History and monuments

[edit]The fortress of Saimbeyli may be the castle of Berdus, which appears on the Coronation List of King Levon I of Cilician Armenia in A.D. 1198/99.[4] This fortress, which guards the strategic road between Kayseri to the north and the Rubenid castle of Vahka to the south, stands on the junction of two valleys and two tributaries of the Seyhan River. The plan and masonry of Saimbeyli’s castle are identical to the military architecture in the Armenian Kingdom of Cilicia and undoubtedly date from the mid-12th century to the 13th century.

Opposite and below the fortress are the substantial remains of ecclesiastical and civilian architecture, which date from the 14th through the 19th century.[5]

An Armenian monastic complex dedicated to St. James is perched on the side of a tall hill at the northwest end of the village. It stood on a 12th century foundation, but it was rebuilt in 1554 by Bishop Khatchadour[6] and was purposefully desecrated during the Adana massacres of the Armenian genocide, leaving little remains.

Violence consumed Marash and Hadjin during the Adana massacres of April 1909, when estimates of the death toll grew to exceed 5,000.[7] Rose Lambert, an American missionary at Hadjin, wrote in her book how many sought refuge in the missionary compound for safety.[8] Reports to British authorities surfaced that imperial Ottoman leaders were "either indifferent or conniving in the slaughter."[7]

Some order was restored by April 20, and the British cruiser HMS Swiftsure was able to deliver "provisions and medicines intended for Adana."[10] A "threatening" report from Hadjin indicated that well-armed Armenians were held up in the town, "beleaguered by Moslem tribesmen who are only awaiting sufficient numerical strength to rush the improvised defenses erected by the Armenians."[10] 8,000 such refugees filled the missions of Tarsus, where order had been restored under martial law, the dead numbering approximately 50.[10]

An April 22 message from an American missionary in Hadjin indicated that the town was taking fire intermittently, surrounding Armenian properties had been burned, and that siege was inevitable. The entirety of the Armenian population of Kırıkhan was reported to have been "slaughtered"; the Armenian village of Dörtyol was burning and surrounded; additional bloodshed flared up in Tarsus; massacres were reported in Antioch, and rioting in Birejik.[11]

Population

[edit]At the beginning of the 20th century, Hadjin had an Armenian population of around 30,000. The Armenians had six churches, including the main Armenian Apostolic denomination, but also an Armenian Catholic and two Evangelical Armenian churches. The population worked in agriculture and various trades. They were subject to deportations and massacres during the Armenian genocide. After the end of World War I, in 1919, part of the Armenian population returned under the French Protectorate, but the French abandoned the city to Turkish rule, resulting in the Armenian rebellion and the eventual emptying of the city with the arrival of the Kemalist forces. The remaining Armenian population of Hadjin settled in various countries, notably Lebanon, Syria, France, the United States and Latin American countries. They established unions highlighting their city and achievements of its populations.

The Turkish authorities renamed the city Saimbeyli in the name of the Turkish military commander that retook the city under Turkish control.

In 1953, a town called Nor Hachn (New Hadjin) was founded in the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic (now Armenia) in memory of the city of Hadjin in Turkey. According to a census of 2015, Nor Hachn has a population of 9,400, The town also includes in its population some survivors and descendants of survivors of the genocide and a memorial built in memory of the Armenian victims of Hadjin and the Hadjin resistance. The memorial itself was inaugurated in 1974.

Composition

[edit]There are 28 neighbourhoods in Saimbeyli District:[12]

Places of interest

[edit]- Near the village of Bahçeköyü there is a castle perched on a rock.

- Saimbeyli castle (known as Badimon in the Middle Ages)

References

[edit]- ^ a b "Address-based population registration system (ADNKS) results dated 31 December 2022, Favorite Reports" (XLS). TÜİK. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Büyükşehir İlçe Belediyesi, Turkey Civil Administration Departments Inventory. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ "İl ve İlçe Yüz ölçümleri". General Directorate of Mapping. Retrieved 12 July 2023.

- ^ Edwards, Robert W. (1987). The Fortifications of Armenian Cilicia: Dumbarton Oaks Studies XXIII. Washington, D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks, Trustees for Harvard University. pp. 208–211, 279, 285, pls.185a-188b. ISBN 0-88402-163-7.

- ^ Robert W. Edwards, "Ecclesiastical Architecture in the Fortifications of Armenian Cilicia: Second Report," Dumbarton Oaks Papers 37, 1983, pp.125–28, 130–31, pls. 10–17, 30–34.

- ^ Alishan, G. (1899). Sissouan ou l’Arméno-Cilicie. Description géographique et historique. Venice. pp. 174–177.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b "MOSLEM MASSACRES TAKE 5,000 LIVES". The New York Times. April 21, 1909.

- ^ Lambert, Rose (1911). Hadjin and the Armenian Massacres. Revell.

- ^ Woods, H. Charles (1911). "The Armenian Massacres of April, 1909". The Danger Zone of Europe: Changes and Problems in the Near East. Boston: Little, Brown. p. 127.

- ^ a b c "Foreign Cruisers at Mersina". The New York Times. April 23, 1909.

- ^ "AMERICAN WOMEN IN PERIL AT HADJIN". The New York Times. April 23, 1909.

- ^ Mahalle, Turkey Civil Administration Departments Inventory. Retrieved 12 July 2023.