Calicut kingdom

Kingdom of Calicut | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1124–1806 | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Status | Kingdom | ||||||||

| Capital | Calicut | ||||||||

| Common languages | Malayalam | ||||||||

| Religion | Hinduism | ||||||||

| Government | Feudal Monarchy | ||||||||

| Zamorin | |||||||||

• 1124–1132 | Mana Vikrama | ||||||||

• 1798–1806 | Krishna Varma | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

• Dissolution of the Cheras of Cranganore[1] | 1124 | ||||||||

| 1766-1792 | |||||||||

| 1806 | |||||||||

| Currency | Kozhikode Panam | ||||||||

| |||||||||

| Today part of | India | ||||||||

The Kingdom of Kozhikode (Malayalam: കോഴിക്കോട് [koːɻikːoːɖ] ), also known as Calicut, was the kingdom of the Zamorin of Calicut, in the present-day Indian state of Kerala. Present-day Kozhikode is the second largest city in Kerala, as well as the headquarters of Kozhikode district.

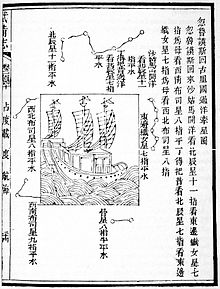

Kozhikode was dubbed the "City of Spices" for its role as the major trading point of eastern spices[2] during the Middle Ages and probably as early as Classical antiquity. The port at Kozhikode held the superior economic and political position in medieval Kerala coast, while Kannur, Kollam, and Kochi, were commercially important secondary ports, where the traders from various parts of the world would gather.[3] It was once the capital of an independent kingdom by the same name and later of the erstwhile Malabar District. The port at Kozhikode acted as the gateway to medieval South Indian coast for the Persians, the Arabs, the Chinese, and finally the Europeans.[4]

Foundation

[edit]

The ancient port of Tyndis which was located on the northern side of Muziris, as mentioned in the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, was somewhere around Kozhikode.[5] Its exact location is a matter of dispute.[5] The suggested locations are Ponnani, Tanur, Beypore-Chaliyam-Kadalundi-Vallikkunnu, and Koyilandy.[5] Tyndis was a major center of trade, next only to Muziris, between the Cheras and the Roman Empire.[6] Pliny the Elder (1st century CE) states that the port of Tyndis was located at the northwestern border of Keprobotos (Chera dynasty).[7] The North Malabar region, which lies north of the port at Tyndis, was ruled by the kingdom of Ezhimala during Sangam period.[8] According to the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea, a region known as Limyrike began at Naura and Tyndis. However the Ptolemy mentions only Tyndis as the Limyrike's starting point. The region probably ended at Kanyakumari; it thus roughly corresponds to the present-day Malabar Coast. The value of Rome's annual trade with the region was estimated at around 50,000,000 sesterces.[9] Pliny the Elder mentioned that Limyrike was prone by pirates.[10] The Cosmas Indicopleustes mentioned that the Limyrike was a source of peppers.[11][12]

During the Sangam period (3rd – 4th century BC), the land where Kozhikode now stands was an uninhabited region of the Chera Empire. This land, part of the larger Tamilakam partly fell within the Kudanad (Western land; west of Kongunad) to the south and partly within Puzhinad (marshy tract) to the north. The dominion of the Cheras extended as far as present-day Vatakara, beyond which lay the kingdom of Eli (Ezhi). The ports of the Chera empire played an important role in fostering trade relations between Kerala and the outside world. According to scholars, Tyndis or Tondi (present-day Kadalundi or Ponnani) to the south of Kozhikode was a flourishing seaport. During the 9th century, this region became a part of the Second Chera Empire. The Cheras (also known as Perumals) ruled the territory until 1102.

The rise of Calicut as a major trading centre and a port city does not seem to have happened before the 13th century. The Zamorin of Calicut was originally the ruler of Eranad, which was a minor principality located in the northern parts of present-day Malappuram district.[13][8] His headquarters was Nediyiruppu in Kondotty.[8][13] Later it was the Eradi (The ruler of Eranad), who came to be known as Zamorin, and developed the port at Kozhikode.[8][13] Eranad was ruled by a Samanthan Nair clan known as Eradis, similar to the Vellodis of neighbouring Valluvanad and Nedungadis of Nedunganad. The rulers of Eranad were known by the title Eralppad/Eradi. While the first reference to the Kingdom of Calicut and Saamoothiri is made by Ibn Battuta in his accounts (1342–1347), there is no reference to Calicut by Marco Polo, who visited Kerala towards the end of the 13th Century. He does, however, mention the kingdom of Eli. This provides a clue to a plausible date for the rise of Calicut as a major kingdom on the Kerala coast. Nevertheless, Prof. Krishna Ayyar has assigned 1034 CE as the year of the foundation of the city.[14]

According to the Keralolpathi (Genesis of Kerala), the last of the Chera kings, Cheraman Perumal, partitioned the kingdom among his feudatories and secretly left for Mecca with some Arab traders where he embraced Islam and lived the rest of his life in obscurity in Arabia. The date of this partition is a significant turning point in the history of Kerala. It is now clear that the Cheraman Perumals ruled in the 8th, 9th and 10th centuries and that the last Cheraman Perumal was Rama Varma Kulasekhara (1089–1102). Although there is no basis for the last Perumal's conversion to Islam and pilgrimage to Mecca, it is now accepted that following his mysterious disappearance the land was partitioned and that the governors of different Nadus (fiefdoms) gained independence, proclaiming it as their 'gift' from the last sovereign.[15]

There is some ambiguity regarding the exact course of events that led to the establishment of the zamorin's rule over Calicut. According to Prof. A. Sreedhara Menon (who entirely rejects the story of Cheraman Perumal's disappearance, his conversion to Islam and the subsequent gifts to his feudatories), immediately following the 'fall' of the Rama Kulasekhara, Calicut and its suburbs formed part of the Polanad Kingdom ruled by the Porlatiri, which was a vassal state to the Kolathunadu based at North Malabar.[16] The Eradis of Nediyirippu in Ernad (somewhere around present Kondotty) were land-locked and sought an outlet to the sea to initiate trade and commerce with distant lands.[17] To accomplish this, the Eradis marched with their nairs towards Panniyankara and besieged the Porlatiri in his headquarters, resulting in a 50-year war. The Eradis emerged victorious in their conquest of Polanad. After this, Menokkis were made as the ruler of Polanad and came to terms with the troops and people.[18] After this, the town of Calicut was founded close to the palace at Tali.[19] Then, the Eradis shifted their headquarters from Nediyirippu to Calicut. The Governor of Ernad built a fort at a place called Velapuram to safeguard his new interests. The fort most likely lent its name to Koyil Kotta the precursor to Calicut.

However, M.G.S. Narayanan in his book, Calicut: The City of Truth states that the Governor of Eranad, Mana Vikrama (who became the Zamorin of Calicut later) was, in fact, a favourite of the last Ceraman Perumal, Rama Kulasekara as the former was at the forefront of the wars with the Chola-Pandya forces to the South and led the army to victory.[15] The King, therefore, granted him, as a mark of favour, a small tract of land on the sea-coast in addition to his hereditary possessions. This patch of wasteland is called Cullikkad in the Keralolpathi. To corroborate his assertion that Mana Vikrama was, in fact, a favourite of the last Perumal, Narayanan cites a stone inscription of the last ruler (1102) discovered at Kollam in South Kerala. It refers to Nalu taliyum ayiram arunurruvarum eranadu vazhkai Manavikiraman mutalayulla camantarum-'The four Councillors, The Thousand, The Six Hundred, along with Mana Vikrama, the Governor of Eranad and other Feudatories'.

However, the Eradis[20] being land-locked lacked direct access to the coastline as the territory of Polanad (Porakilanad) lay between Eranad and Calicut. Having been given the royal sword and the injunction Cattum konnum adakki kolka (conquer by courting and conferring death) by the last Ceraman (according to Keralolpathi), the Ernad Utayavar (Governor) waged war against the Porlatiri (Porakilar Adhikari) and attacked Panniyankara. M.G.S seems to indicate that the land sought by the Ernadis, lay in fact beyond and not within the kingdom of Polanad.

With the conquest of Polanad, the status of the Utayavar (Governor) increased and he came to be known as Swami Nambiyathiri Thirumulpad and the Kingdom of Calicut also came to known as Nediyiruppu Swarupam after the original house of the Eradis at Nediyiruppu. The king's title gradually evolved into Samoothirippadu or Saamoothiri or Saamoori over the years. The Europeans called him Zamorin. The foundation of the city of Calicut was therefore laid during the initial years of the 12th century. The Sweetmeat Street (Mittayi Theruvu) was an important trading street under Zamorin's rule.

In the 14th century, Kozhikode conquered larger parts of central Kerala after the seize of Tirunavaya region from Valluvanad, which were under the control of the king of Perumbadappu Swaroopam (Cochin). The ruler of Perumpadappu was forced to shift his capital (c. CE 1405) further south from Kodungallur to Kochi. In the 15th century, the status of Cochin was reduced to a vassal state of Kozhikode, thus leading to the emergence of Kozhikode as the most powerful kingdom in medieval Malabar Coast.[4]

The history of Kozhikode can roughly be divided into several periods marked by a few epoch-making events. These include the city's establishment, the arrival of the Portuguese, the arrival of the Dutch, the Mysorean Invasion, the rise of British Power, the beginning of the Indian Independence Movement and finally freedom from British rule in 1947.

Society and Organization

[edit]According to the Chinese traveler Ma Huan, who describes visiting Calicut in the Yingya Shenglan, Calicut was a place with relative harmony between its Hindu and Muslim populations, with a Hindu king making compact with Muslim lords to refrain from eating pork (per Islamic dietary laws), so long as they did not eat beef. Huan also described worship of Moses existing in addition to Islam and Hinduism, which Huan mistakenly identified as Buddhism. Additionally detailed was the existence of a complex system of measurements for trade, as well as a system of succession in which the king's sister's son inherited the throne, due to a belief that legal family only constituted those born from a woman within said family; if no such heir existed, the throne would be passed to "some man of merit."[21]

Arrival of the Portuguese

[edit]

This single event marked an epoch in the history of Kerala and India, not because Vasco da Gama discovered the sea route to India (the Chinese, the Arab and Turkish sultanates, and the African kingdoms already traded directly with India) but, unlike the others, the Portuguese yearned for political power and imperial domination. Vasco da Gama's fame is more often argued as due to historical reasons for which he was hardly responsible[22] in that he was accompanied by a Portuguese-speaking Arab merchant provided by the Sultan of Melinda in East Africa. Vasco da Gama was sent by King Manuel I and landed in Calicut at Kappad in 17 May 1498.[23] Following the discovery of a sea route from Europe to Malabar in 1498, the Portuguese began to expand their territories and ruled the seas between Ormus and the Malabar Coast and south to Ceylon.[24][25] The navigator was received with traditional hospitality, but an interview with the Zamorin failed to produce any concrete results. Vasco da Gama's request for permission to leave a factor behind him in charge of the merchandise he could not sell was declined by the King, who insisted that da Gama pay customs duty like any other trader, straining the relationship between the two. The next expedition was sent by the King of Portugal under the leadership of Pedro Álvares Cabral in 1500. His agent secured a settlement to erect a factory at Calicut. This, however, precipitated matters between the Arabs and the Portuguese. The Portuguese capture of Arab vessels and ensuing massacre was retaliated by the locals who burned down the factory and butchered half of the Portuguese on land. Cabral sailed for Cochin, where he was cordially received and allowed to load his ships. Vasco da Gama reached Calicut the second time with 15 ships and 800 men in February 1502. In January 1502, the First Battle of Cannanore between the Third Portuguese Armada and Kingdom of Cochin under João da Nova and Zamorin of Kozhikode's navy marked the beginning of Portuguese conflicts in the Indian Ocean. When da Gama's call to expel all Muslims from Calicut was vehemently turned down, he bombarded the city and captured several rice vessels, cutting off the crew's hands, ears, and noses.

With rising bonhomie between the Maharaja of Cochin and the Portuguese, there followed several wars in which the Portuguese propped up Cochin and Cannanore against the Zamorin. Scores of men perished in these wars on all sides starting in 1503 and continuing till the early 1570s. In February 1509, the defeat of the joint fleet of the Sultan of Gujarat, the Mamlûk Burji Sultanate of Egypt, and the Zamorin of Calicut with support of the Republic of Venice and the Ottoman Empire in Battle of Diu marked the beginning of Portuguese dominance of the Spice trade and the Indian Ocean. In the same year, Afonso de Albuquerque was appointed the second Viceroy of the Portuguese possessions in the East. A new fleet under Marshall Coutinho arrived with specific instructions to destroy the power of Calicut. The Zamorin's palace was captured and destroyed and the city was set on fire. But the King's forces rallied fast to kill Marshall Coutinho and wounded Albuquerque. Albuquerque nevertheless was clever enough to patch up his quarrel and entered into a treaty with the Zamorin in 1513 to protect Portuguese interests in Kerala. Hostilities were renewed when the Portuguese attempted to assassinate the Zamorin sometime between 1515 and 1518. From the 1520s the Zamorin's naval fleet was administered by the Kunjali Marakkars who inflicted heavy damages to Portuguese property till 1589. King Zamorin was assisted mainly by four ministers namely Mangatachan the Chief Minister, Dharmoth Panicker, Army Chief and Teacher of Martial Arts, Kuthiravatathu Nair, Finance Minister and Kunjali Marakars, Chief of Naval Force.[5]

In 1503, the Portuguese had built a fort in Chaliyam with the consent of the Raja of the Kingdom of Tanur (Vettattnad) from where they re-established supremacy over Indian waters. It provided the Portuguese ample opportunities to harass the Zamorin and enter the heart of his kingdom in the event of war. The Chaliyam fort was 'like a pistol held at the Zamorin's throat'. The Zamorin attacked Chaliyam and recaptured the fort in 1571 coinciding with the defeat of the ruler of Vijayanagara, an ally of the Portuguese. The Portuguese were forced to abandon the fort, which was then completely demolished. The fall of Chaliyam fort marked the beginning of the end for the Portuguese in the great game of the East. The Portuguese approached the Zamorin again in 1578 for reconciliation. By 1588 they were settled in Calicut and in 1591 built a church on land donated by the Zamorin (who even laid the foundation stone). The Zamorin's growing friendship was nevertheless a result of his gradual estrangement with the Kunjali Marakkars.

By 1663, the Portuguese flag ceased to fly in Kerala as the Dutch arrived at the scene and captured all their strongholds of Quilon, Cranganore, Purakkadm, Cochin and Cannanore.

Arrival of the Dutch

[edit]

In 1602, the Zamorin sent messages to Aceh promising the Dutch a fort at Kozhikode if they would come and trade there. Two factors, Hans de Wolff and Lafer, were sent on an Asian ship from Aceh, but the two were captured by the chief of Tanur, and handed over to the Portuguese.[26] A Dutch fleet under Admiral Steven van der Hagen arrived at Kozhikode in November 1604. It marked the beginning of the Dutch presence in Kerala and they concluded a treaty with Kozhikode on 11 November 1604, which was also the first treaty that the Dutch East India Company made with an Indian ruler.[8] By this time the kingdom and the port of Kozhikode was much reduced in importance.[26] The treaty provided for a mutual alliance between the two to expel the Portuguese from Malabar. In return the Dutch East India Company was given facilities for trade at Kozhikode and Ponnani, including spacious storehouses.[26] It provided for a mutual alliance between the Zamorin and the Dutch to expel the Portuguese from Indian soil. In return, they were given facilities for trade at Calicut, including spacious storehouses. In the 18th century the Dutch position weakened and they were forced to surrender to a British force that marched from Calicut to Cochin on 20 October 1795 (as part of the larger Napoleonic Wars between Holland and England in Europe). Travancore became the most dominant state in Kerala by defeating the powerful Zamorin of Kozhikode in the battle of Purakkad in 1755.[27]

The Mysore invasions

[edit]Hyder Ali ascended the throne of Mysore in 1761. By 1764, he obtained a pledge of neutrality from the British at Tellicherry in the event of a conflict with the Kerala powers. In February 1766, Hyder Ali marched into northern Kerala. Except for a few decisive battles, he faced meagre opposition and entered Calicut. The Zamorin sent the members of his family to Ponnani, blew up his palace and to avoid the humiliation of surrender, and committed self-immolation. A revenue officer named Madanna was appointed as the Civil Governor of Malabar with headquarters at Calicut. A rebellion soon broke out and the Mysorean garrison was besieged by the Nairs. Hyder Ali rushed to crush the rebellion, devastating the countryside and employing draconian measures to suppress the Nairs including defrocking of their social status. Successfully achieving his objectives, he had to return to Mysore soon to deal with the Maratha threat. A rebellion broke out again. Hyder Ali engaged in diplomacy this time through Madanna and agreed to withdraw his forces for which a war indemnity was to be paid to him. But he made a second attempt in December 1773 and re-established his authority in Malabar. However, with the help of the British, the Nairs led by the famous Ravi Varma of Padinjare Kovilakam, wiped out the Mysorean garrison in Calicut by 1778. By 1783 Tipu Sultan established his authority over Northern Kerala. He planned to shift the capital from Calicut to the south of the city on the banks of the river Chaliyar and even named it 'Farookhabad' now called Feroke. This ambitious plan soon failed. In November 1788, Calicut was attacked by the Nairs under Ravi Varma of the Padinjare Kovilakam. Tipu returned in 1789 to re-establish his authority. This, however, brought him in direct conflict with the British based in Madras, which resulted in four Anglo-Mysore Wars. Calicut and the surrounding districts were among the territories ceded to the British after the Third Anglo-Mysore War by the Treaties of Seringapatam with the British on 22 February and 18 March 1792. The newly acquired possessions on the Malabar Coast were organised into the Malabar District of Madras Presidency, and Calicut became the district capital.

British domination

[edit]

The arrival of British in Kerala can be traced back to the year 1615, when a group under the leadership of Captain William Keeling arrived at Kozhikode, using three ships.[4] It was in these ships that Sir Thomas Roe went to visit Jahangir, the fourth Mughal emperor, as British envoy.[4] The British concluded a treaty of trade under which, among others, the English were to assist Calicut in expelling the Portuguese from Cochin and Cranganore, a term that the British never fulfilled. In 1664, Zamorin gave the English permission to build a factory in Calicut but did not extend any other favours as he was by now growing suspicious of all European traders. The English maintained neutrality in the conflict between Mysore and the Kerala powers in 1766 and was an important factor which facilitated early success to Hyder Ali. However, tensions between the English and Mysore arose soon. The English army under Major Abington helped Ravi Varma of Padinjare Kovilakam in the recapture of Calicut in 1782 from Mysore. The East India Company however did not stand by Lord Cornwallis' promise to the exiled rulers that they will be restored after the expulsion of Tipu. By 1792, the whole of Malabar including Calicut came under the British dominion. Ravi Varma now turned against the company but was soon captured in 1793. The rebellion continued even after the capture of Ravi Varma till 1797. Under British Raj, it acted as the headquarters of Malabar District, one of the two districts in the western coast of erstwhile Madras Presidency. During the British rule, Malabar's chief importance lay in producing pepper.[28] Kozhikode municipality was formed on 1 November 1866 according to the Madras Act 10 of 1865 (Amendment of the Improvements in Towns act 1850)[29][30][31][32] of the British Indian Empire, making it the first modern municipality in the state.

National movement

[edit]The city also witnessed several movements as part of the struggle for Indian independence from the British. A conference of the Congress was held at Calicut in 1904 with C. Vijayaraghavachariar in the chair. A branch of the All India Home Rule League founded by Ms. Annie Besant started functioning in the city. In 1916, Sri K.P.Kesava Menon staged a walk out of the Town Hall when he was denied permission by the Collector Mr Innes to address the meeting in Malayalam. The period saw a rise in political journalism as well. The Mathrubhumi in March 1923 and Al Amin in October 1924 were started by Sri K.P.Kesava Menon and Muhammad Abdur Rahiman respectively to foster the spirit of Nationalism. On 12 May 1930, Satyagrahi's assembled at Calicut beach under the leadership of Muhammad Abdur Rahiman to break the 'Salt laws' were attacked by the police injuring more than 30 people. K.P.Krishna Pillai and R.V.Sharma defended the National flag from forcible seizure by the police on this occasion. During the Second Civil Disobedience Movement (1932), all four hundred delegates who attended the All Kerala Political Conference in September 1932 were arrested. The incident wherein Mrs L.S.Prabhu (of Thalassery), who courted arrest during the conference, was ordered to surrender all her gold ornaments including the tali or mangalsutra received nationwide condemnation. Calicut was also a major centre for the rising Communist Party of Malabar (1939) and the Quit India Movement (1942). Kerala chapter of the Communist Party was formed in a secret meeting held at Kallai Road in the year 1937.

After Indian Independence in 1947, Madras Presidency was renamed the Madras State. In 1956 when the Indian states were reorganised along linguistic lines, Malabar District was combined with the state of Travancore-Cochin to form the new state of Kerala on 1 November 1956. Malabar District was later split into the districts of Kannur, Kozhikode, and Palakkad on 1 January 1957. Kozhikode was upgraded as a Municipal Corporation in 1962, making it the second-oldest Municipal Corporation in the state.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ M. G. S. Narayanan, Perumals of Kerala: Brahmin Oligarchy and Ritual Monarchy – Political and Social Conditions of Kerala Under the Cera Perumals of Makotai (c. AD 800–AD 1124). Kerala. Calicut University Press, 1996, pp. 512.

- ^ "Lectures 26–27". Purdue University. Archived from the original on 16 July 2009. Retrieved 23 September 2009.

- ^ The Portuguese, Indian Ocean and European Bridgeheads 1500–1800. Festschrift in Honour of Prof. K. S. Mathew (2001). Edited by: Pius Malekandathil and T. Jamal Mohammed. Fundacoa Oriente. Institute for Research in Social Sciences and Humanities of MESHAR (Kerala).

- ^ a b c d Sreedhara Menon, A. (January 2007). Kerala Charitram (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. ISBN 978-81-264-1588-5. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ a b c d Menon, A. Sreedhara (2007). A Survey of Kerala History. DC Books. ISBN 9788126415786.

- ^ Coastal Histories: Society and Ecology in Pre-modern India, Yogesh Sharma, Primus Books 2010

- ^ Gurukkal, R., & Whittaker, D. (2001). In search of Muziris. Journal of Roman Archaeology, 14, 334–350.

- ^ a b c d e Sreedhara Menon, A. (January 2007). Kerala Charitram (2007 ed.). Kottayam: DC Books. ISBN 978-81-264-1588-5. Archived from the original on 13 November 2021. Retrieved 19 July 2020.

- ^ According to Pliny the Elder, goods from India were sold in the Empire at 100 times their original purchase price. See [1]

- ^ Bostock, John (1855). "26 (Voyages to India)". Pliny the Elder, The Natural History. London: Taylor and Francis.

- ^ Indicopleustes, Cosmas (1897). Christian Topography. 11. United Kingdom: The Tertullian Project. pp. 358–373.

- ^ Das, Santosh Kumar (2006). The Economic History of Ancient India. Genesis Publishing Pvt Ltd. p. 301.

- ^ a b c K. V. Krishna Iyer (1938). Zamorins of Calicut: From the earliest times to AD 1806. Norman Printing Bureau, Kozhikode.

- ^ Ayyar, K.V. Krishna, The Zamorins of Calicut- From the Earliest Times to A.D.1806(1938), Calicut.

- ^ a b M.G.S. Narayanan,Calicut: The City of Truth(2006) Calicut University Publications

- ^ Sreedhara Menon.A,A Survey of Kerala History(1967),p.152. D.C.Books Kottayam

- ^ Bhāratīya sthalanāma patrikā (page 44) published by Place Names Society of India

- ^ Sewell, Robert (1884). Lists of inscriptions, and sketch of the dynasties of southern India. E. Keys at the Government Press. p. 197.

The Zamorin made Menokki ruler of Porallatiri and came to terms with the troops and people. After this follows an account of the founding of the town of Calicut, close to the Zamorin's palace at Tali

- ^ K. V. Krishna Ayyar; University of Calicut. Publication Division (1938). The zamorins of Calicut: from the earliest times down to A.D. 1806. Publication Division, University of Calicut. p. 82. ISBN 978-81-7748-000-9. Archived from the original on 14 April 2023. Retrieved 22 September 2016.

- ^ Divakaran, Kattakada (2005). Kerala Sanchaaram. Trivandrum: Z Library.

- ^ Ma Huan, "Ying-Yai Sheng-Lang," pages 138-146.

- ^ Panickar.K.M, A History of Kerala(1959) Annamalai University

- ^ "Portuguese (1505–1961)". myeduphilic. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 5 November 2017.

- ^ Sanjay Subrahmanyam, The Career and Legend of Vasco da Gama, Cambridge University Press, 1997, 288

- ^ Knox, Robert (1681). An Historical Relation of the Island Ceylon. London: Reprint. Asian Educational Services. pp. 19–47.

- ^ a b c Sanjay Subrahmanyam. "The Political Economy of Commerce: Southern India 1500–1650". Cambridge University Press, 2002

- ^ Shungoony Menon, P. (1878). A History of Travancore from the Earliest Times (pdf). Madras: Higgin Botham & Co. pp. 162–164. Retrieved 5 May 2016.

- ^ Pamela Nightingale, ‘Jonathan Duncan (bap. 1756, d. 1811)’, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2009

- ^ "CHRONOLOGICAL LIST OF CENTRAL ACTS (Updated up to 17-10-2014)". Lawmin.nic.in. Archived from the original on 7 January 2018. Retrieved 7 August 2016.

- ^ Lewis McIver, G. Stokes (1883). Imperial Census of 1881 Operations and Results in the Presidency of Madras ((Vol II) ed.). Madras: E.Keys at the Government Press. p. 444. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 5 December 2020.

- ^ Presidency, Madras (India (1915). Madras District Gazetteers, Statistical Appendix For Malabar District (Vol.2 ed.). Madras: The Superintendent, Government Press. p. 20. Archived from the original on 27 March 2023. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

- ^ HENRY FROWDE, M.A., Imperial Gazetteer of India (1908–1909). Imperial Gazetteer of India (New ed.). Oxford: Clarendon Press. Archived from the original on 16 December 2008. Retrieved 2 December 2020.

Further reading

[edit]- K. V. Krishna Iyer (1938), Zamorins of Calicut: From the earliest times to AD 1806, Norman Printing Bureau, Kozhikode

- M. G. S. Narayanan, Calicut: The City of Truth Revisited Kerala. University of Calicut, 2006

- A. Sreedhara Menon, A Survey of Kerala History, (1967), Madras, 1991

- S. Muhammad Hussain Nainar (1942), Tuhfat-al-Mujahidin: An Historical Work in The Arabic Language, University of Madras, retrieved 3 December 2020 (The English translation of the historic book Tuhfat Ul Mujahideen written about the society of Kozhikode by Zainuddin Makhdoom II during sixteenth century CE)