North Pier, Blackpool

Blackpool's North Pier, viewed from the top of Blackpool Tower | |

| Type | Pleasure Pier with Landing Jetty |

|---|---|

| Official name | North Pier |

| Owner | Blackpool Pier Company |

| Characteristics | |

| Total length | 550 yards (500 m) |

| History | |

| Designer | Eugenius Birch |

| Opening date | 21 May 1863 |

| Coordinates | 53°49′08″N 3°03′33″W / 53.8190°N 3.0593°W |

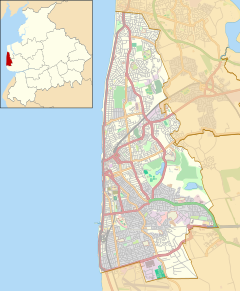

North Pier is the most northerly of the three coastal piers in Blackpool, England. Built in the 1860s, it is also the oldest and longest of the three. Although originally intended only as a promenade, competition forced the pier to widen its attractions to include theatres and bars. Unlike Blackpool's other piers, which attracted the working classes with open air dancing and amusements, North Pier catered for the "better-class" market, with orchestra concerts and respectable comedians. Until 2011, it was the only Blackpool pier that consistently charged admission.

The pier is designated by English Heritage as a Grade II listed building, due to its status as the oldest surviving pier created by Eugenius Birch. As of 2021, it is still in regular use, despite having suffered damage from fires, storms and collisions with boats. Its attractions include bars, a theatre, a carousel and an arcade. One of the oldest remaining Sooty glove puppets is on display commemorating Harry Corbett buying the original puppet there.

Location

[edit]North Pier was built at the seaward end of Talbot Road, where the town's first railway station, Blackpool North, was built.[1] Its name reflects its location as the most northerly of Blackpool's three piers. It is about 450 yards (410 m) north of Blackpool Tower, which is roughly the midpoint of Blackpool's promenade. The sea front is particularly straight and flat on this stretch of coastline, and the 550 yards (500 m) pier[1] extends at right angles into the Irish Sea, more or less level with the promenade.

History

[edit]

The construction of Blackpool Pier (eventually North Pier) started in May 1862, in Layton-cum-Warbreck, part of the parish of Bispham.[2] In October 1862 severe storms suggested that the planned height of the pier was insufficient, and it was increased by 3 feet (0.91 m).[2] North Pier was the second of fourteen piers designed by Eugenius Birch, and since Margate Pier was destroyed by a storm in 1978, it is the oldest of the remaining examples of his work still in use.[3] It was the first of Birch's piers to be built by Glasgow engineering firm Richard Laidlaw and Son.[2]

The pier, which cost £11,740 to build,[4] originally consisted of a promenade 468 yards (428 m) long and 9 yards (8.2 m) wide, extending to 18 yards (16 m) wide at the pier-head. The bulk of the pier was constructed from cast iron, with a wooden deck laid on top. The cast iron piles on which the structure rests were inserted using Birch's screw pile process; the screw-tipped piles were twisted into the sand until they hit bedrock. This made construction much quicker and easier, and guaranteed that the pier had a solid foundation.[5] The cast iron columns, 12 inches (300 mm) in diameter, were filled with concrete for stability at intervals of 20 yards (18 m), and supported by struts that were on average were slightly more than 1 inch (25 mm) thick.[2] The pier's promenade deck is lined with wooden benches with ornamental cast iron backs. At intervals along the pier are hexagonal kiosks built around 1900 in wood and glass with minaret roofs topped with decorative finials.[6] On opening two of the kiosks were occupied by a bookstall and confectionery stall and the kiosks near the ends of the pier were seated shelters.[4] The pier-head is a combination of 420 tons of cast iron and 340 tons of wrought iron[4] columns; standing 50 feet (15 m) above the low water line, it sees a regular 35 feet (11 m) change in sea level due to the tide.[2]

Opening

[edit]

The pier was officially opened in a grand ceremony on 21 May 1863, even though the final 50 yards (46 m) had not yet been completed. All the shops in the area were closed and decorated with flags and streamers[4] for the ceremony, which included a procession and a cannon salute, and was attended by more than 20,000 visitors.[7] Although the town only had a population of approximately 4,000, more than 200,000 holiday makers regularly stayed there during the summer months;[2] this included 275,000 admissions in 1863, 400,000 in 1864 and 465,000 the following year.[4] The pier was officially opened by Major Preston, and he and 150 officials then travelled to the Clifton Hotel for a celebratory meal.[4]

The pier was intended primarily for leisure rather than seafaring; for the price of 2d (worth approximately £4.90 in 2012)[note 1] the pier provided the opportunity for visitors to walk close to the sea without distractions.[8] This fee was insufficient to deter "trippers'", which led to Major Preston campaigning for a new pier to cater for the 'trippers'.[4] In 1866, the government agreed that a second pier could be built, despite objections from the Blackpool Pier Company that it was close to their pier and therefore unnecessary.[9]

19th century

[edit]As permitted by the original parliamentary order, a landing jetty was built at the end of North Pier in incremental stages between 1864 and 1867. The full length of the jetty was 158 yards (144 m), and the extensions increased the pier's total length to its current 550 yards (500 m).[1] The Blackpool Pier Company used the jetty to operate pleasure steamers that made trips to the surrounding areas.[1][10] In 1871 swimming and diving lessons were added to the pier.[4]

In 1874, the pier-head was extended to allow Richard Knill Freeman to incorporate a pavilion, which opened in 1877.[10] The interior decoration led it to be known as the "Indian Pavilion", and it was Blackpool's primary venue for indoor entertainment until the Winter Gardens opened in 1879.[11]

To differentiate itself from the new pier, North Pier focused on catering for the "better classes", charging for entry and including attractions such as an orchestra[12] and band concerts,[4] in contrast to the Central Pier (or the "People's pier"), which regularly had music playing and open-air dancing.[13] The pier owners highlighted the difference, charging at least a shilling (worth approximately £19.90 in 2012)[note 2] for concerts and ensuring that advertisements for comedians focused on their lack of vulgarity. Sundays were given over to a church parade.[14]

On 8 October 1892, a storm-damaged vessel, Sirene, hit the southern side of the pier, causing four shops and part of the deck to collapse onto the beach below. Several columns were also dislodged, and the ship's bowsprit hit the pier entrance. All eleven crew members were rescued when they were hauled onto the pier. Damage to the pier was estimated to be £5,000 and was promptly repaired.[4]

Nelson's former flagship, HMS Foudroyant, was moored alongside North Pier for an exhibition, but slipped anchor and was wrecked on the shore in a violent storm on 16 June 1897, damaging part of the jetty. The wreck of the ship broke up during December storms.[15]

The pier was closed for the winter during 1895–96 as it was unsafe; as a result, the pier was widened as electric lighting was added.[4]

20th century

[edit]

An Arcade Pavilion was added in 1903 at the entrance to the pier and contained a wide range of amusements to suit all tastes. Further alterations were made to the pier in 1932-33 when the open air stand was replaced with a stage and sun lounge.[4]

In 1936, a pleasure steamer returning from Llandudno crashed into the pier. The collision left a 10 feet (3.0 m) gap, and stranded a number of people at the far end.[16]

The 1874 Indian Pavilion was severely damaged by fire in 1921. It was refurbished, but was then destroyed by a second fire in 1938. In 1939 it was replaced by a theatre, built in an Art Deco style.[1][17] At around the same time, the bandstand was removed and replaced with a sun lounge.

In the 1960s, the Merrie England bar and an amusement arcade were constructed at the end of the pier nearest to the shore. The 1939 theatre, which is still in use, narrowly escaped damage in 1985 when the early stages of a fire were noticed by performer Vince Hill. In the 1980s, a Victorian-styled entrance was built. In 1991 the pier gained the Carousel bar as an additional attraction, and a small tramway to ease access to the pier-head.[18] By this point, the pier had ceased to have any nautical use, but the jetty section was adapted for use as a helicopter pad in the late 1980s.[1] The Christmas Eve storm of 1997 destroyed the landing jetty, including the helipad.[19]

The North Pier is one of the few remaining examples of Birch's classic pier architecture and is a Grade II Listed building, the only Blackpool pier to hold that status.[6][20] It was recognised as "Pier of the Year" in 2004 by the National Piers Society.[21]

Attractions

[edit]

North Pier's attractions include a Gypsy palm reader and an ice cream parlour, the North Pier Theatre, a Victorian tea room, and the Carousel and Merrie England bars. The arcade, built in the 1960s, has approximately eleven million coins pass through its machines each year.[22]

One of the earliest Sooty bear puppets used by Harry Corbett is on display on the pier. Corbett bought the original Sooty puppet on North Pier for his son, Matthew. When Corbett took the puppet on BBC's Talent Night programme, he marked the nose and ears with soot so that they would show up on the black and white television, giving the puppet its name.[23]

The Carousel bar on the pier-head has a Victorian wrought iron canopy, and its outdoor sun-lounge is classified as the largest beer garden in Blackpool. Next to the bar is a two tier carousel, the "Venetian Carousel", which is protected from sand and spray by a glass wall.[24]

After the fire in 1938, the pavilion was replaced with a 1,564-seat theatre which has since hosted a number of acts including; Frankie Vaughan, Frank Randle, Tessie O'Shea, Dave Morris, Bernard Delfont, Morecambe and Wise, Paul Daniels, Freddie Starr, Russ Abbot, Bruce Forsyth, Des O'Connor, Joe Longthorne, Cannon & Ball, Lily Savage, Brian Conley and Hale and Pace.[4] In 2020, the theatre was renamed the Joe Longthorne Theatre, in memory of Longthorne who had died the year before and who had performed there for over 20 seasons.[25]

In 2002 a heritage room with photographs was opened up, the foyer entrance was refurbished and a disabled lift added. By 2005, there was no longer a live organist playing in the sun lounge although other live entertainment continues.[4] In 2013, the live organist was brought back into the sun lounge.

Ownership

[edit]The pier was built and owned by the Blackpool Pier Company, created with three thousand £5-shares in 1861 (worth approximately £2,990 in 2012).[note 3] The same firm operated the pier in 1953,[26] and the company was incorporated in 1965.[27] The Resorts Division of First Leisure, including the pier, was sold to Leisure Parks for £74 million in 1998.[4] In 2009, the pier was sold to the Six Piers group, which owns Blackpool's other two piers, and hoped to use it as a more tranquil alternative to them.[28] The new owners opened the Victorian-themed tea room, and built an eight-seat shuttle running the length of the pier.[29]

In April 2011, the pier was sold to a Blackpool family firm, Sedgwick's, the owners of amusement arcades and the big wheel on Blackpool's Central Pier. Peter Sedgwick explained that he proposed to his wife on North Pier forty years ago, and promised to buy it for her one day.[30] He said that he wants to restore the Victorian heritage of the pier and re-instate the pier's tram. An admission charge of fifty pence to access the board-walk section of the pier was abolished by the Sedgwicks.[31]

Liquidation

[edit]A petition to wind up the Northern Victorian Pier Limited (the company used by the Sedgwick family to manage Blackpool North Pier) was presented on 17 September 2012 by Carlsberg UK Limited, a creditor of the company, and this was to be heard at Blackpool County Court on 15 November 2012.[32]

At the 11th hour, an agreement to pay the outstanding balance owed to Carlsberg was made and Peter Sedgwick's company escaped liquidation.[33]

See also

[edit]- Listed buildings in Blackpool

- Central Pier, Blackpool

- South Pier, Blackpool

- List of piers in the United Kingdom

Notes

[edit]- ^ Comparing average earnings between 1863 and 2012, 2 old pence is valued at approximately £4.90 by MeasuringWorth.com

- ^ Comparing average earnings between 1879 and 2012, 1 shilling is valued at approximately £19.90 by MeasuringWorth.com

- ^ Comparing average earnings between 1861 and 2012, £5 is valued at approximately £2,990.00 by MeasuringWorth.com

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f "History – Blackpool North Pier". North Pier official site. Archived from the original on 25 February 2012. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f "Blackpool pier". The Builder. 21: 406. 1863. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ "Margate Pier". National Piers Society. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Easdown, Martin (2009). "Chapter 7: The Three Piers of Blackpool". Lancashire Seaside Piers. Barnsley, England: Wharncliffe Books. pp. 98–115. ISBN 9781845630935.

- ^ "New Pier at Blackpool, Lancashire". The Civil Engineer and Architect's Journal. 26: 162. 1 June 1863. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ a b Historic England, "North Pier, Blackpool (1205766)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 30 August 2013

- ^ "The Opening of Blackpool Pier". The Illustrated London News. 20 May 1863. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ Walton, John K.; Cross, Gary S. (1990). Worktowners at Blackpool: Mass-Observation and Popular Leisure in the 1930s. Routledge. pp. 83–84. ISBN 978-0-203-99329-3.

- ^ House of Commons papers, Volume 66. HMSO. 1866. pp. 2–3.

- ^ a b Rennison, Robert William (1996). Civil Engineering Heritage: Northern England (2nd ed.). Thomas Telford. pp. 213–214. ISBN 0-7277-2518-1.

- ^ "History of Blackpool" (PDF). Visit Blackpool. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 June 2010. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ Jones, Karen R.; Wills, John (2005). The Invention of the Park: Recreational Landscapes from the Garden of Eden to Disney's Magic Kingdom. Polity. p. 93. ISBN 0-7456-3138-X.

Blackpool Victoria pier.

- ^ Walton, John K.; Cross, Gary S. (2005). The Playful Crowd: Pleasure Places in the Twentieth Century. Columbia Univ. Press. pp. 24, 64–65. ISBN 0-231-12724-3.

blackpool south pier.

- ^ Walton, John (1986). "Residential amenity, respectable morality and the rise of the entertainment industry: The case of Blackpool, 1860–1914". In Waites, Bernard; Bennett, Tony; Martin, Graham (eds.). Popular Culture Past and Present. Croom Helm. p. 140. ISBN 0-7099-1909-3.

- ^ Gossett, William Patrick (1986). The Lost Ships of the Royal Navy, 1793–1900. Mansell. p. 125. ISBN 0-7201-1816-6.

- ^ "Blackpool pier is rammed by steamer". Montreal Gazette. 29 August 1936. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Blackpool Theatres". The Grand Theatre official site. Archived from the original on 25 January 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ "Past Scape: North Pier". English Heritage. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Helicopter rides may return to the Prom". Blackpool Gazette. 6 December 2004. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ Gibson, Lisanne; Pendlebury, John (2009). Valuing Historic Environments. Ashgate. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-7546-7424-5.

- ^ Wills, Anthony. "Media Watch". National Piers Society. Archived from the original on 11 March 2012. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ Holman, Tom (2010). A Lancashire Miscellany. Frances Lincoln. p. 99. ISBN 978-0-7112-3093-4.

- ^ "Rare Sooty puppet sold at auction". BBC News. 29 October 2008. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Carousel Bar & Sun Lounge". North Pier official site. Archived from the original on 7 February 2012. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Joe Longthorne Theatre (former North Pier Pavilion)". Theatres Trust. Retrieved 19 April 2024.

- ^ "Blackpool Gains over '51 with a net of 425G". Billboard. 17 January 1953. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ "Blackpool Pier Company Ltd". Companies House. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ "Prince of the piers". Blackpool Gazette. 18 May 2009. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "All about the "wow"". Blackpool Gazette. 17 March 2010. Retrieved 9 February 2012.

- ^ "Blackpool's North Pier buyer's pledge to wife". BBC News. 12 April 2011. Retrieved 8 February 2012.

- ^ "'Free for all' after North Pier is sold". Blackpool Gazette. 2 April 2011. Retrieved 14 February 2012.

- ^ "Winding up Petition". London Gazette. 11 October 2012. Retrieved 11 October 2012.

- ^ "Agreement to Pay Made". TheBusinessDesk.com. 26 November 2012. Retrieved 26 November 2012.

External links

[edit]- Blackpool's North Pier History

- Engineering timelines – Details of the pier's construction

- http://citytransport.info/B-Piera.htm – Some photographs of the diesel tramway on the pier.

- Blackpool North Pier Entertainment Display