Nuruosmaniye Mosque

| Nuruosmaniye Mosque | |

|---|---|

| |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Sunni Islam |

| Location | |

| Location | Istanbul, Turkey |

| Geographic coordinates | 41°00′37″N 28°58′14″E / 41.010234°N 28.970540°E |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Simon Kalfa |

| Type | Mosque |

| Style | Ottoman Baroque |

| Groundbreaking | 1748 |

| Completed | 1755 |

| Specifications | |

| Height (max) | 43.5 metres (143 feet) |

| Dome dia. (inner) | 25 metres (82 feet) |

| Minaret(s) | 2 |

The Nuruosmaniye Mosque (Turkish: Nuruosmaniye Camii) is an 18th-century Ottoman mosque located in the Çemberlitaş neighbourhood of Fatih district in Istanbul, Turkey, which was inscribed in the Tentative list of World Heritage Sites in Turkey in 2016.[1]

Designed by a Greek non-Muslim architect named Simeon Kalfa, the Nuruosmaniye mosque was the first monumental Ottoman building to exemplify the new Ottoman baroque style, which introduced baroque and neoclassical elements from Europe.[2][3][4][5] The mosque's ornamentation and its curved courtyard display its baroque influences. The dome of the mosque is one of the largest in Istanbul. The mosque is part of a larger religious complex, or külliye, acting as a centre of culture, religion, and education for the neighborhood.

In Constantinople, the area of the Nurosmaniye Mosque was close to the Forum of Constantine, where the Column of Constantine (Turkish: Çemberlitaş Sütunu) still stands. Surrounding the mosque is Istanbul's Grand Bazaar (Turkish: Kapalıçarşı). After the construction of the Sultan Ahmed Mosque, the Nurosmaniye mosque was the first imperial mosque to be built in 100 years.[6]

Historical background

[edit]

The construction of the mosque complex was commissioned on the order of Sultan Mahmud I in 1748 and completed under his brother and successor, Sultan Osman III, in 1755. It was named Nuruosmaniye, meaning "The light of Osman", after Osman III.[6]

The construction of the Nuruosmaniye marked the first time since the construction of the Sultan Ahmed I Mosque (in the early 17th century) that an Ottoman sultan built his own imperial mosque in Istanbul, something which had previously been a tradition with every sultan. Mahmud I's foundation marked the return of this tradition.[7] The mosque was also the first monumental Ottoman building to exemplify the new Ottoman Baroque style, influenced by contemporary Baroque architecture in Europe.[6][8][3] It helped reshape the city of Istanbul by announcing this new imperial style and marking a definitive shift away from Classical Ottoman architecture.[9][6]

The complex was built on Istanbul's second hill. According to Ahmed Efendi, an Ottoman secretary involved in the mosque's construction, the site was formerly occupied by a smaller mosque founded by a certain Fatma Hatun.[10] By the 18th century, this mosque had fallen into disrepair and the local residents had already petitioned Sultan Ahmed III to renovate it, but to no avail. When a new petition was sent to Mahmud I, the sultan appointed an official to investigate and it was ascertained that the mosque's waqf (endowment) was no longer generating income. Instead of funding its renovation, the sultan decided to appropriate the waqf and use the site for the construction of a new mosque.[11] This much larger construction, however, required the purchase of multiple properties in the surrounding area, which initially met with reluctance from the property owners.[12]

Mahmud I was known for his personal interest in architecture and Ahmed Efendi's writings seem to emphasize the sultan's personal commitment and piety in relation to the project.[12] In his account, Efendi adds a story in which Mahmud I, while visiting the construction site, came across a "blessed sage" or spiritual old man. The sage praised him for building the mosque and bringing joy to the neighbourhood, and prayed for God to reward the sultan, thus encouraging Mahmud I to continue the project.[12][13] Although Efendi's account has a panegyric style, it suggests that the sultan and his entourage viewed the mosque's construction as the fulfilment of divine providence and that a certain religious aura was promoted around the project.[12] A number of other 18th-century Ottoman writers also praised the mosque after completion, signaling its perceived importance at the time. Although several of them, including Efendi, praised the size of the dome, they do not make any clear comments about the building's novel architectural style.[5][14]

The mosque was designed by a non-Muslim Greek architect named Simeon Kalfa or Simon Kalfa.[15][3][4][16] This was the first non-Muslim architect to be placed in charge of a major imperial Ottoman construction.[5] Simeon's chief assistant was a Christian man named Kozma and the majority of the stonemasons under him were Christians as well. Both Simeon and Kozma were given robes of honour by the grand vizier at the mosque's opening ceremony.[17] Scholar Ünver Rüstem notes this may have been the first time Christian architects were officially honoured at the inauguration of a mosque and that it reflected the growing status of Christian craftsmen in Ottoman architecture during this era.[16]

Architecture

[edit]The mosque

[edit]

The prayer hall is covered by a single dome 25.4 metres (83 ft) in diameter[5] and 43.5 metres (143 ft) high above the floor level.[18] This makes it the third largest historic dome in Istanbul, after the Hagia Sophia and the Süleymaniye Mosque.[5][a] The mosque utilizes a system of iron bracing running up from the floor, through the walls, and to the ceiling of the dome.[19] The mosque material is made out of cut stone and marble.[20]

From the outside, the dome sits above four huge arches (one for each side of the square) pierced with many windows that provide light to the interior. The closest precedent to this design in Classical Ottoman architecture is the Mihrimah Sultan Mosque in the Edirnekapi neighbourhood of Istanbul.[21][22] The projecting apse which contains the mihrab is also comparable to the Selimiye Mosque in Edirne.[21] The complex has two minarets, each with two balconies. The courtyard of the mosque is designed in the shape of a horseshoe, unprecedented in Ottoman mosques.[8]

The decoration and details of the mosque are firmly in the Ottoman Baroque style, which was new at the time.[23][24] The general form of the building is described as "straining everywhere to melt straight lines into curves."[25] The curving pediments above the exterior arches have concave flourishes at their edges, while the windows, doorways, and arches of the mosque have mixtilinear (i.e. combination of different curves) or round profiles instead of traditional pointed arch profiles.[23][24] The central doorway of the courtyard is topped by an unusual radiating sun motif carved in stone while the other doorways have pyramidal semi-vaults which, instead of the traditional muqarnas, are carved with many rows of acanthus-like friezes and other motifs – a composition that is neither Ottoman nor European in style.[26]

Inside, the mosque's prayer hall is flanked by symmetrical two-story galleries that extend outside the main perimeter of the hall. The corners of these galleries, on either side of the mihrab area, include a space for the muezzins on one side and a space for the sultan's loge (hünkâr mahfili) on the other, thus dispensing with the traditional müezzin mahfili platform in the middle of the mosque. This gallery arrangement leaves the central space unencumbered while still dissimulating the supporting piers of the dome.[27] The most exuberant Baroque carvings, such as flutes and scroll forms, are found on the minbar.[28] The hood of the mihrab, like the semi-vaults above the exterior doorways, is carved with a mix of eclectic friezes that replace the traditional muqarnas.[29] The mosque's stone decoration also establishes a new style of capitals that distinguishes the Ottoman Baroque: a vase or inverse bell shape, either plain or decorated, usually with small but prominent volutes at its corners, similar to Ionic capitals.[30][31] The prayer hall is also lined with golden Qur'anic calligraphy and has medallions with name of Allah and Muhammad on the pendentives of the dome.

- Details of the mosque

-

Mosque exterior, looking to the walls of the prayer hall

-

One of the minarets

-

Exterior arches and windows

-

Mosque exterior, looking to the walls of the courtyard

-

Central entrance to the courtyard, with sun motif above the doorway

-

Courtyard of the mosque

-

Detail of Baroque carving above the prayer hall's courtyard entrance, replacing the traditional muqarnas

-

Interior of the prayer hall, looking southeast towards the mihrab area

-

Interior of the dome

-

Gallery inside the prayer hall, with sultan's loge on the upper level

-

Apse containing the mihrab, with the minbar on the right

-

Detail of the mihrab

-

Exterior view of the mihrab apse

Other structures of the complex

[edit]The mosque complex, or külliye, also contains numerous other structures contributing to its role as a religious and charitable complex, enclosed in a precinct of irregular shape, bounded by streets on each side. The sites slope downward in the north area.[18] The mosque compound has two gates, the east and west gates. The western gate faces the edge of the Grand Bazaar.[20] Although some of the auxiliary buildings have traditional floor plans, their details are consistently executed in the new baroque style.[32]

Attached directly to the mosque on its northeast side is the hünkâr kasrı, a three-story, L-shaped building that granted private access to the mosque for the sultan and his family. An indoor ramp near the precinct's eastern entrance climbs up to a private lounge and reception area (selamlık). From here, the sultan could pass directly to the hünkâr mahfili within the prayer hall.[33][1] This type of annex existed in some earlier imperial mosques of the 17th century, but in the Nuruosmaniye complex it is more prominent and more deliberately integrated with the mosque.[32][34]

The library occupies the northeastern corner of the precinct and has an oval floor plan.[7] It includes a reading room and a book storage area. It was originally opened with a collection of 5031 volumes, though this number changed much over the years. Some 152 books had been lost by the beginning of the 20th century. In 1923, 34 volumes of historic value were transferred to the Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum. Today, the collection includes 5048 books, including more recent private donations.[35] On the south side of the library is a türbe (domed tomb) with a traditional floor plan.[32] It is not certain who the tomb was originally intended for, but it was used to house the remains of Shehsuvar Sultan, mother of Osman III, who died in 1756.[7]

On the south side of the complex is the madrasa (Islamic college) and the imaret (public soup kitchen), which form one building with two sections. The madrasa occupies the eastern section and consists of a square courtyard surrounded by an arcaded portico and domed rooms, a fairly traditional layout.[36][32] The imaret occupies the western side and consists of smaller rectangular courtyard surrounded by a variety of rooms.[36]

The sebil is located next to the western entrance, integrated into the exterior wall of the compound. It was traditionally used for dispersing water to the public and to aid ablutions before prayer. It is currently used as a carpet store. An ornate wall fountain is also located nearby, on the other side of the entrance.[37]

- Auxiliary structures

-

Eastern entrance to the mosque complex

-

Western entrance to the mosque complex, with the fountain on the left and the sebil on the right

-

The sebil

-

The hünkâr kasrı: a ramp on the right leads to the sultan's pavilion (private lounge) connected to the mosque on the left

-

Inside the ramp of the hünkâr kasrı

-

The tomb (left) and library (right), at the northeastern corner of the complex

-

Entrance and north side of the library

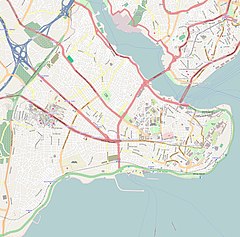

Location

[edit]

The mosque stands on the second hill of Istanbul. The location of the complex is one surrounded by many shops, businesses, and the Grand Bazaar. The complex is also located just across the street from one of the entrances to the Grand Bazaar. The Column of Constantine, the historic Gazi Atik Ali Pasha Mosque, and the modern Çemberlitaş tram station are all located directly south of the mosque.

Being such a prosperous and commercially active area, the Sultan knew it would be a convenient location for Muslims to attend prayer. It would also serve as a reminder to the people of the presence of the state and the Sultan during a time of political and economic misfortune.[citation needed]

Restoration (2010–2012)

[edit]The complex has been re-decorated several times over the course of its life, but a combination of environmental factors, lack of maintenance, air pollution, and original building flaws substantially degraded the state of the complex. As a result, from 2010 to 2012 a 20-million-lira (US$3.5 million)[38] renovation campaign was conducted by FOM group architects. The most severe issue of the complex was one of water. The leaking domes were resealed with a close-to-original lead coating and applied in traditional fashion, the drainage systems were cleared of rubble and revamped, and the basements were renovated. The walls of the mosque had been heavily blackened, required sand blasting and pressure washing. Other components of the mosque such as marble, timber, iron, and glass were cut and replaced if severely deteriorated.[citation needed]

During the restoration campaign, several discoveries were made that further the status of the mosque as an architectural achievement and historic site:

- In the process of scraping old deteriorated laminar ornaments, even older hand drawn ornaments were found, preserved, and set on display.[citation needed]

- The discovery of an active cistern underneath the mosque, which by word of Foundations Istanbul Provincial Director İbrahim Özekinci required the removal of "420 trucks’ worth of slime from the cistern. Then the magnificent gallery, cistern and water gauge became visible. The Ottomans used a modern system according to contemporary earthquake regulations."[39] The cistern covers an area 2,242 square meters, boasts 825 square meters (8,880 sq.ft.) of usable area, and is being considered as a future location for a museum.[citation needed]

- It was discovered that the mosque sits on an older structure that was built using a bored-pile foundation. The oldest bored-pile foundation in the history of Turkish architecture found to date.[40]

Current role

[edit]A historic site and notable landmark in Istanbul tourism, the mosque is used daily as a place of worship. In 2018 the Yeditepe Biennial art exhibition, organized under the administration of Turkish president Recep Tayyip Erdoğan,[41] utilized the cistern of the complex to display works of art that showcased both traditional and modern Turkish art.[42]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ According to Ahmed Efendi, the dome of the original Fatih Mosque at the time was also larger.[5]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b "Nuruosmaniye Complex". UNESCO World Heritage Centre. UNESCO. Retrieved 8 June 2018.

- ^ "Nuruosmaniye Complex". whc.unesco.org. UNESCO. Retrieved 2023-04-27.

- ^ a b c Freely, John (2000). Inside the Seraglio: Private Lives of the Sultans in Istanbul. Penguin Books. p. 211. ISBN 978-0-14-027056-3.

- ^ a b Freely, John; Glyn, Anthony (2000). The Companion Guide to Istanbul and Around the Marmara. Boydell & Brewer. p. 104. ISBN 978-1-900639-31-6.

- ^ a b c d e f Suman, Selva (2011). "Questioning an "Icon of Change": The Nuruosmaniye Complex and the Writing of Ottoman Architectural History" (PDF). METU Journal of the Faculty of Architecture: 145–166. doi:10.4305/METU.JFA.2011.2.7.

- ^ a b c d Rüstem 2019, p. 111.

- ^ a b c Rüstem 2019, p. 115.

- ^ a b Goodwin 1971, pp. 381–387.

- ^ Kuban 2010, p. 526.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, pp. 119–120.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, p. 120.

- ^ a b c d Rüstem 2019, p. 121.

- ^ Efendi, Ahmed (1919) [18th century]. Târih-i Câmi'-i Şerif-i Nûr-i Osmani. Istanbul: Hilāl Matbaası.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, p. 150.

- ^ Goodwin 1971, p. 386.

- ^ a b Rüstem 2019, pp. 147–148.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, p. 147.

- ^ a b "Nuruosmaniye Külliyesi". Archnet. Retrieved 2019-12-09.

- ^ Saliba, Nada (2019). "The Significance and Representation of the Nuruosmaniye Mosque as a Baroque Monument". Chronos. 21: 167–186. doi:10.31377/chr.v21i0.486.

- ^ a b Rüstem 2019.

- ^ a b Kuban 2010, p. 532.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, p. 137.

- ^ a b Rüstem 2019, pp. 138–145.

- ^ a b Kuban 2010, pp. 532, 536.

- ^ Levey, Michael (1975). The World of Ottoman Art. London: Thames and Hudson. OCLC 182637845.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, pp. 139–140.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, pp. 141–144.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, pp. 144–145.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, p. 145.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, p. 146.

- ^ Goodwin 1971, p. 388.

- ^ a b c d Kuban 2010, p. 536.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, p. 125.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, pp. 128–130.

- ^ Erünsal, İsmail E. (2007). "NURUOSMANİYE KÜTÜPHANESİ". TDV İslâm Ansiklopedisi (in Turkish). Retrieved 2023-04-28.

- ^ a b Rüstem 2019, pp. 113–115.

- ^ Rüstem 2019, pp. 112–115.

- ^ "Still-active cistern beneath Istanbul mosque". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 2019-11-22.

- ^ "Still-active cistern beneath Istanbul mosque". Hürriyet Daily News. Retrieved 2019-11-23.

- ^ "Structure similar to Basilica Cistern found under mosque". worldbulletin.net/ (in Turkish). Retrieved 2019-11-24.

- ^ "T.C.CUMHURBAŞKANLIĞI : "Son 15 yılda diğer birçok alanda olduğu gibi kültür ve sanat alanında da tabuları yıktık"". www.tccb.gov.tr. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

- ^ "Biennial | Yeditepe Bienali". www.yeditepebienali.com. Retrieved 2019-12-04.

Sources

[edit]- Goodwin, Godfrey (1971). A History of Ottoman Architecture. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 0-500-27429-0.

- Kuban, Doğan (2010). Ottoman Architecture. Translated by Mill, Adair. Antique Collectors' Club. ISBN 9781851496044.

- Rüstem, Ünver (2019). Ottoman Baroque: The Architectural Refashioning of Eighteenth-Century Istanbul. Princeton University Press. ISBN 9780691181875.

External links

[edit]- Nuruosmaniye Complex at ArchNet.org

- Nuruosmaniye Mosque at GreatIstanbul.com

- Images of Nuruosmaniye Mosque

- 19th century images of mosque