Painted Cave, Galdar

| Painted cave, Las Palmas | |

|---|---|

| Native name Cueva Pintada (Spanish) | |

Painted cave in Galdar, Grand Canary Island | |

| Location | 2, Audiencia street, Galdar, Grand Canary, Canary Islands, Spain |

| Coordinates | 28°08′38.4324″N 15°39′18.4860″W / 28.144009000°N 15.655135000°W |

| Area | ~5,000 m2[1] |

| Visitors | 54,190 (in 2015)[2] |

| Website | Painted cave museum and archaeological park |

| Official name | Cueva Pintada |

| Type | Cultural |

| Designated | 25 May 1972: Historic Artistic monument; 19 November 1990: Property of Cultural Interest |

| Reference no. | RI-55-0000273 |

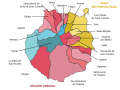

Location of the Painted cave and Galdar on Grand Canary, Canary Islands | |

The Painted cave is an archaeological museum and park in the town of Galdar, located the northwest of Grand Canary in the Canary Islands, Spain. This centre is part of the Spanish Ministry of Culture, Historic Heritage and Museums of the town council of Grand Canary.

Inside are found some of the most representative archaeological vestiges of pre-Hispanic Canaries, with characteristics unique within Spain. The Painted cave is considered as the "Sistine chapel" of the former inhabitants of the island, the Canarii.

Location

[edit]The Painted cave is located at nº 2 Audiencia street, in the centre of Gáldar, 27 km west of Las Palmas and 50 km N-W of the international airport of Gran Canaria.[3]

Discovery and evolution

[edit]The cave was discovered in 1862 on the occasion of agricultural works, through a hole in its roof. The "official discovery" had to wait until 1873, when José Ramos Orihuela visited the cave.

In 1876, Gregorio Chil y Naranjo[note 1] briefly mentions the cave in his "Studies".

In 1882 Diego Ripoche[note 2] visited the cave and made drawings, some of which he may have sent to René Verneau. He also noted the presence of corpses, pots and other utensils.

In 1884, Olivia Stone[note 3] visited the cave, made some drawings, wrote about it and suggested that the local government should acquire the site and take proper care of it.

In 1887, French anthropologist René Verneau visited the cave. He wrote a detailed description in which he mentions the careful execution of each painted panel.

The end of the 19th century is noted for a revival in the awareness of the importance of conservation issues for historical works. In the El Museo Canario review, chronicler Batllori y Lorenzo writes "Mi última tentativa", a solemn appeal for the protection of the cave. Critics of the institutions' lack of action in that direction continue into the 20th century. But only in 1967 starts a public campaign in favour of the cave's protection - counting among its supporters Celso Martín de Guzmán and Elías Serra Ráfols.

Meanwhile, the paintings were deteriorating. In 1970 the General commission of archaeological excavations ("Comisaría General de Excavaciones Arqueológicas") started working on the protection of the cave, notably on the humidity that was causing much damage. This was completed with the construction of an enclosure to protect the cave - and the public. In 1972 the site was declared Monument historique artistique.[4]

Antonio Beltrán and José Miguel Alzola realized the first systematic study, published in 1974 with the first colour photographies and the most exact drawings to that date. This was another big step into spreading the knowledge of the existence of the cave among the specialists. It also helped determine the deterioration of the paintings. The plantations being watered nearby, the inadequate protection of the enclosure, the absence of planning for the visits, the chemical soil treatments for agricultural purposes and the inadequate ventilation of the premises were the main factors in increasing temperature and humidity in the cave and the subsequent damage on the paintings. Expropriation procedures were then started regarding the cultivated nearby land, and the site was closed to the public in October 1982.[4]

The Painted cave museum and archaeological park of Galdar was reopened on 26 July 2006,[5] after 24 years excavating and restoring the site, and fitting it for public visits without further endangerment of the paintings and other historic items. Up to then it was only possible to see a reproduction of the paintings in the Canary Museum of Las Palmas in Grand Canary. Entry is open from 10 a.m. to 6 p.m. All visits are accompanied with a guide and must be booked.[6] Four languages are available.[7]

In 2016 the museum celebrated its 10th anniversary by sharing an exchange with the cave of Altamira museum - each museum lending to the other tens of its most valuable pieces.[8]

Description

[edit]

The Painted cave

[edit]The cave is a superb example of artistic representations of the ancient natives of Gran Canaria. It and the village next to it are located in the town that used to be the capital of the island in pre-Hispanic times.[1]

Excavated by humans in volcanic material, its walls are decorated with geometrical patterns.[6] The archaeologists think that, due to their regular distribution (usually in series of twelve), they could be a sort of calendar.

It is also the only location on Gran Canaria that brought the proof of the existence of common wheat on the island (triticum aestivum or triticum durum, as it is difficult to tell the difference from the seed grain).[9][note 4] Note that Grand Canary is the only Canarian Island to have painted caves.[10]

Utensils

[edit]The site also bears remains of houses, in which have been found various utensils. The collection counts among other items some notable locally-made decorated ceramic pots and paintings. It also include some ceramics made on pottery wheel on the continent as well as coins, swords, horseshoes, nails, everyday use items (thimbles, knives, etc.).[11] Most coins are from the 15th and 16th centuries. It seems that all metal items were imported.[12]

Some pots are large and were used for storage; others were used for cooking. The local pottery was hand-made, with many of them presenting a finely polished surface and decorated with paint, generally ochre red applied before firing them in a hole in the ground. Some pots are entirely covered with geometrical patterns, in some cases including the bottom of the pots.[13] Note that Gran Canaria is the only Canary island where painted pottery has been found.[14]

Beside these, are some fired clay statues of idols with human and animal figures. Most of the human idols are feminine and many are associated with maternity. In some cases the statues' bodies have been decorated with red paint and some incisions mark the hair. These could be simple offerings, amulets or toys.[15]

There are needles, stamps and spatulas made of sheep or goat bones; the needles are related to the making of leather clothes; the stamps and spatulas were pottery tools.[16]

Objects made of stone have also been found. The stones most used are basalts, phonolites and obsidians. The stones were worked to create sharp edges with which to work other raw materials (wood, bone, skin/leather) or to carry out other works such as meat cutting or food preparation. Basalt was also used to make mortars, some round and some of elongated shapes. Some round mortars were used to grind grain for flour, some others for the red ochre that was used for the paintings and to decorate the pots.[17]

The settlement

[edit]

Over twenty years of excavations have unveiled a whole settlement beyond the Painted cave. A whole hamlet used to spread from the bottom of the valley up to the present city centre. This was one of the neighbourhoods that constituted pre-Hispanic Agaldar. The hamlet was occupied from the 6th century until the 11th century, and again from the 13th century until the 16th century and the Spanish conquest of the island.[18]

The houses were quadrangular and were surrounded outside by circular walls. They had one or two lateral bedrooms, opening towards the south through a small corridor. The bedrock was used to lean walls against it, and was worked to form a flat floor in the houses. The floor was further covered with packed earth or, in some cases, of stones sometimes coloured with red ochre.[18][19]

The walls were made either of basalt or of well-dressed blocks of tuff. Nearly all the houses have kept remains of mortar and of paints of various colours that decorated the rooms.[18]

The enclave has an important role in the understanding of the final stage of pre-Hispanic Canaries - before the conquest - and the incorporation of the island to the crown of Castille.

It is of note that some of the main artificial cave sites of the island are located in the relative vicinity of the Painted cave (cuevas del Hospital, Huertas del Rey or the Audience cave in the Four Doors cave site).[20][note 5]

Dating the site

[edit]The first carbon-14 analysis made on the cave was on the wall paintings. This gave no results because the paint used carried no trace of carbon, being entirely non-organic (ochre). Then some vegetal remains of a plant from the family Lauraceae were found in the mortar in the walls. These remains were analysed by the CSIC laboratory and that of the French CNRS, and dated between 1049 and 1257 A.C. Some fragments of pine tree were dated between 601 and 994.[21]

Services

[edit]The Painted Cave Museum and Archaeological Park pursues:

- The conservation, cataloguing and exhibition of the archaeological artefacts in its custody, as well as the management and conservation of the site.

- The development of a program of educational actions and of diffusion with regard to its contents and thematics.

- The research within its speciality, keeping in mind the ones directly related with the conservation of the decorated room.[22]

Specific services

[edit]The vocation of the centre to promote the aspects of conservation, research and diffusion is embodied in the existence of facilities adapted to the achievement of these aims:

In the didactic classroom is carried out a program of activities aimed at education centres and at all visitors interested in furthering their knowledge of our ancestors.

Both the laboratories and the library make it possible for researchers and restorers to develop the tasks to make the Painted cave museum and archaeological park a centre of reference for the production and diffusion of scientific knowledge.

A multi-purpose room completes the facilities.[22]

A well-patronized site

[edit]The site has registered 34.616 visitors in 2006 over the first 5 months of it reopening, and 513,880 visitors in the 9,5 years up to December 2015. The monthly average is around 50,000 visitors, slowly increasing as years go by.[2] This makes it one of the most visited places in the Canary Islands and indeed in the whole of Spain, and places the site at the level of the major archaeological sites in Europe. The average appreciation of the visit is very high, with a 9.15/10 note given by the visitors - an exceptional success.[23] The majority of visitors in 2006-2007 were young (under 20 y.o.) local students,[23] but from 2012 to 2015 half of the visitors are in the 30-60 y.o.

Publications

[edit]- (in Spanish) Virtual archaeology review, May 2010. Article pp. 26–29: "Los escenarios históricos en el Museo y Parque Arqueológico Cueva Pintada: de la investigación a la recreación virtual".

- (in Spanish) La conservación en la musealización de la Cueva Pintada - De la investigación a la intervención ("Conservation and musealisation of the Painted cave - From investigation to intervention")

- (in Spanish) Conference Musealización Santiago de Compostela 2006: El Museo y Parque Arqueológico Cueva Pintada (Gáldar, Gran Canaria): de manzana agrícola a parque arqueológico urbano ("the Painted cave museum and archaeological park (Galdar, Grand Canary): from an agriculture unit to an urban archaeological park")

- (in Spanish) 2nd international encounter on technologies on museography (ICOM Spain): Painted cave museum and archaeological park of Galdar

- (in Spanish) Arminda's adventures: an integral project of education and diffusion in the Painted cave museum and archaeological park

- (in Spanish) Troglodyte heritage of Grand Canary

- (in Spanish) Tourism, heritage and education

- (in Spanish) Visit guide

- (in Spanish) Magazine Museo 1999

- (in Spanish) Magazine archaeological researches

- (in Spanish) Cultural heritage 4

See also

[edit]External links

[edit]- (in Spanish) Cueva Pintada, official site

- (in Spanish) Jorge Onrubia Pintado, José Ignacio Sáenz Sagasti, Carmen Gloria Rodríguez Santana. La conservación en la musealización de la Cueva Pintada - De la investigación a la intervención ("Conservation and musealisation of the Painted cave - From investigation to intervention").

Bibliography

[edit]- Verneau, René. Las pintaderas de Gran Canaria. Madrid: Imprenta de Fortanet, 1883.

- Mederos Martin, Alfredo; Escribano Cobo, Gabriel (2002). Los aborígenes y la prehistoria de Canarias. Centro de la Cultura Popular Canaria. ISBN 84-7926-382-2.

Notes and references

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Gregorio Chil y Naranjo (Telde, Gran Canaria, 1831 - Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 1901) was a doctor, anthropologist and historian and one of the leading intellectuals on the Canary Islands at the end of the 19th century. He founded the Canary museum, to which he bequeathed most of his personal possessions. He was excommunicated in 1878 for his work on evolution in the Canary Islands entitled "Estudios historicos, climatologicos y patológicos de las Islas Canarias"; the Bishop of Barcelona, José María de Urquinaona y Vidot, declared the work "falsa, impia, scandalosa y heretica" and excommunicated the doctor. That same Studies became one of the key works on the Canary Islands and is still used as a reference to this day.

- ^ Diego Ripoche Torrens (Las Palmas de Gran Canaria, 1859 - 1927) studied the cave and his work made it known to the scientific community. He lived in Paris for many years.

- ^ Olivia Stone was a British female writer. She visited the Canary Islands between November 1883 and February 1884.

- ^ The cueva de Don Gaspar ("Don Gaspar's cave" in Icod, Tenerife) has revealed grains of triticum compactum ("compact wheat"), barley (Hordeum vulgare L. polystichum) and broad bean (Vicia faba). Bethencourt (a French adventurer from Normandy who conquered 4 of the Canaries islands at the beginning of the 15th century) wrote that in Gran Canaria there were two harvests of wheat per year, without fertilizers. See Mederos Martin & al. (2002), p. 83.

- ^ Although a few caves were dug in isolated locations, most of them are near the sea coast and are concentrated, often in large groups. (source: Mederos Martin & al. 2002, p. 61).

References

[edit]- ^ a b Cueva Pintada de Galdar on gobiernodecanarias.org.

- ^ a b (in Spanish) Painted cave, numbers of visitors 2006-2015 on cuevapintada.com.

- ^ (in Spanish) Painted cave, localisation on cuevapintada.com.

- ^ a b (in Spanish) El descubrimiento de la Cueva Pintada ("The discovery of the Painted cave").

- ^ (in Spanish) Conference Musealización Santiago de Compostela 2006: El Museo y Parque Arqueológico Cueva Pintada (Gáldar, Gran Canaria): de manzana agrícola a parque arqueológico urbano ("the Painted cave museum and archaeological park (Galdar, Grand Canary): from an agriculture unit to an urban archaeological park").

- ^ a b Painted cave museum on grancanaria.com.

- ^ (in Spanish) Cueva Pintada, official site.

- ^ (in Spanish) Aníbal Clemente Cristóbal. La colección del Museo de Altamira se exhibe en la Cueva Pintada (Gran Canaria). July 14, 2016.

- ^ Mederos Martin & al. 2002, p. 83.

- ^ Mederos Martin & al. 2002, p. 141, 152.

- ^ (in Spanish) Painted cave, the collections on cuevapintada.com.

- ^ (in Spanish) Painted cave, imports on cuevapintada.com.

- ^ (in Spanish) Painted cave, the recipients on cuevapintada.com.

- ^ (in Spanish) Amélie A. Walker. Beyond the Beaches of Gran Canaria - Galdar. October 29, 1999.

- ^ (in Spanish) Painted cave, idols on cuevapintada.com.

- ^ (in Spanish) Painted cave, other finds on cuevapintada.com.

- ^ (in Spanish) Painted cave, stone items on cuevapintada.com.

- ^ a b c (in Spanish) Painted cave, the village on cuevapintada.com.

- ^ (in Spanish) Painted cave, the houses on cuevapintada.com.

- ^ Mederos Martin & al. 2002, p. 61.

- ^ La cueva pintada de Gáldar tiene mil años ("The Painted cave is 1,000 years old"). El Mundo, 03/07/2013.

- ^ a b (in Spanish) Painted cave, services. On cuevapintada.com.

- ^ a b (in Spanish) Painted cave, summary of visitors statistics study 2006-2007 on cuevapintada.com.

- ^ (in Spanish) Painted cave visits, study on visitors' statistics on cuevapintada.com.