Pampas

This article needs additional citations for verification. (December 2007) |

Pampas Plain | |

|---|---|

Landscape in the Pampas at eye level in Brazil | |

Approximate location and borders of the Pampas encompassing the southeastern area of South America bordering the Atlantic Ocean | |

| Coordinates: 35°S 62°W / 35°S 62°W | |

| Countries | |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,200,000 km2 (500,000 sq mi) |

| Elevation | 160 m (520 ft) |

| Population | |

• Total | 44,344,847 |

| • Density | 37/km2 (96/sq mi) |

The Pampas (from the Quechua: pampa, meaning "plain"), also known as the Pampas Plain, are fertile South American low grasslands that cover more than 1,200,000 square kilometres (460,000 sq mi) and include the Argentine provinces of Buenos Aires, La Pampa, Santa Fe, Entre Ríos, and Córdoba; all of Uruguay; and Brazil's southernmost state, Rio Grande do Sul. The vast plains are a natural region, interrupted only by the low Ventana and Tandil hills, near Bahía Blanca and Tandil (Argentina), with a height of 1,300 m (4,265 ft) and 500 m (1,640 ft), respectively.

The climate is temperate, with precipitation of 600 to 1,200 mm (23.6 to 47.2 in) that is more or less evenly distributed throughout the year, making the soils appropriate for agriculture. The area is also one of the distinct physiography provinces of the larger Paraná–Paraguay plain division.

It is considered that the limit of the Pampas plain is to the north with the Atlantic Forest and the Great Chaco Plain, to the west with the Pampas Mountains and the Cuyo Region, and to the south with Patagonia.

Topography

[edit]

This region has generally low elevations, whose highest levels generally do not exceed 600 metres (2,000 ft) in altitude. The coastal areas and most of the Buenos Aires Province are predominantly plain (with some wetlands) and the interior areas (mainly in the southern part of the Brazilian state of Rio Grande do Sul and Uruguay) have low ranges of hills (like Serras de Sudeste in Brazil and Cuchilla Grande in Uruguay). Low hills covered by grasslands are called coxilhas (Portuguese pronunciation: [koˈʃiʎɐs]) in Portuguese and cuchillas (Spanish pronunciation: [kuˈtʃiʝas]) in Spanish, and it is the most typical landscape of the countryside areas in the northern parts of the Pampas. The highest elevations of the Pampas region are found in the Sierra de la Ventana mountains, in the southern part of Buenos Aires Province, with 1,239 metres (4,065 ft) at the summit of Cerro Tres Picos.

Climates

[edit]The climate of the Pampas is generally temperate, gradually giving way to a more humid subtropical climate in the north (Cfa, according to the Köppen climate classification, with a Cwa tendency (drier winters) in the northwestern edge); a cold semi-arid climate (BSk) on the southern and western fringes (like San Luis Province, western La Pampa Province and southern Buenos Aires Province); and an oceanic climate (Cfb) in the southeastern part (in the localities of Mar del Plata, Necochea, Tandil and the Sierra de la Ventana mountains, Argentina). Summer temperatures are more uniform than winter temperatures, generally ranging from 28 to 33 °C (82 to 91 °F) during the day. However, most cities in the Pampas occasionally have high temperatures that push 38 °C (100 °F), as occurs when warm, dry, northerly winds blow from southern Brazil, northern Argentina or Paraguay. Autumn arrives gradually in March and peaks in April and May. In April, highs range from 20 to 25 °C (68 to 77 °F) and lows from 9 to 13 °C (48 to 55 °F). The first frosts arrive in mid-April in the south and late May or early June in the north.

Winters are generally mild, but cold waves often occur. Typical temperatures range from 12 to 19 °C (54 to 66 °F) during the day, and from 1 to 6 °C (34 to 43 °F) at night. With strong northerly winds, days of over 25 °C (77 °F) can be recorded almost everywhere, and during cold waves, high temperatures can be only 6 °C (43 °F). Frost occurs everywhere in the Pampas, but it is much more frequent in the southwest than around the Parana and Uruguay Rivers. Temperatures under −5 °C (23 °F) can occur everywhere, but values of −10 °C (14 °F) or lower are confined to the south and west. Snow almost never falls in the northernmost third and is rare and light elsewhere, except for exceptional events in which depths have reached 30 cm (12 in). Springs are very variable; it is warmer than fall in most areas (especially in the west) but significantly colder along the Atlantic. Violent storms are more common as well as wide temperature variations: days of 35 °C (95 °F) can give way to nights of under 5 °C (41 °F) or even frost, all within only a few days.

Precipitation ranges from 1,400 millimetres (55 in) in the northeast to about 400 millimetres (16 in) or less in the southern and western edges. It is highly seasonal in the West, with some places recording averages of 120 millimetres (4.7 in) monthly in the summer, and only 20 millimetres (0.79 in) monthly in the winter. The eastern areas have small peaks in the fall and the spring, with relatively rainy summers and winters that are only slightly drier. However, where summer rain falls as short, heavy storms, winter rain falls mostly as cold drizzle, and so the amount of rainy days is fairly constant. Very intense thunderstorms are common in the spring and summer, and it has among the most frequent lightning and highest convective cloud tops in the world.[1][2] The severe thunderstorms produce intense hailstorms, both floods and flash floods, and the most consistently active tornado region outside the central and southeastern US.[3]

Climate charts

[edit]Climate charts for different locations of the Pampas:

| Bagé, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (1981-2010) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Santa Vitória do Palmar, Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil (1981-2010) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Buenos Aires, Argentina (1981-2010) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Punta del Este, Uruguay (1961-1990) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Viedma, Argentina (1981-2010) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Coronel Suárez, Buenos Aires, Argentina (1981-2010) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Laboulaye, Córdoba, Argentina (1991-2020) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Wildlife

[edit]Human activity has caused major changes to the wildlife of the Pampas. Most big or medium-sized species such as puma, rhea, Capybara, plains viscacha, maned wolf,[4] marsh deer and Pampas deer have lost their habitats especially due to the spread of agriculture and ranching, and are only present in very few relicts of the pampas.[5] Other species, such as the Jaguar and the Guanaco have been extirpated completely from this habitat.

Mammals that are still fairly present include Brazilian guinea pig, southern mountain cavy, coypu, Pampas fox, Geoffroy's cat, lesser grison, white-eared opossum, Molina's hog-nosed skunk, big lutrine opossum, big hairy armadillo and southern long-nosed armadillo. Bird species of the pampas are ruddy-headed goose, pampas meadowlark, hudsonian godwit, maguari stork, white-faced ibis, white-winged coot, southern screamer, dot-winged crake, curve-billed reedhaunter, burrowing owl[6] and the rhea.[7][8][9] Invasive species include the European hare, wild boar and house sparrow.

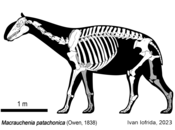

Most of the large mammals native to the Pampas became extinct as part of the end-Pleistocene extinction event of most large mammals across the Americas around 12,000 years ago. Notable former inhabitants of the Pampas include the giant elephant-sized ground sloth Megatherium americanum, along side the smaller (though still large) ground sloths Mylodon, Glossotherium Lestodon and Catonyx, the rhinoceros like ungulate Toxodon, the camel-like Macrauchenia, the gomphothere (elephant-relative) Notiomastodon, the equines Equus neogeus and Hippidion, and the glyptodonts (car-sized relatives of armadillos) Glyptodon and Doedicurus, the bear Arctotherium and the sabertooth cat Smilodon populator.[10]

-

Skeleton of the giant ground sloth Megatherium americanum, a former denizen of the Pampas

-

Skeleton of Toxodon

-

Skeleton of Doedicurus

-

Skeleton of Notiomastodon

-

Skeleton of the equine Hippidion

-

Skeleton of Macrauchenia

-

Skeleton of Smilodon populator

Vegetation

[edit]| Regions of Argentina |

|---|

The dominant vegetation types are grassy prairie and grass steppe, in which numerous species of the grass genus Stipa are particularly conspicuous. "Pampas grass" (Cortaderia selloana) is an iconic species of the Pampas. Vegetation typically includes perennial grasses and herbs. Different strata of grasses occur because of gradients of water availability.

Why the pristine pampas were treeless regions has been much debated. Perhaps the most commonly cited explanation is seasonal drought. A related hypothesis is that grass roots compete for water and exclude tree seedlings. The effect might be increased by heavy, clayed soils which limit tap root penetration. Other causes that have been proposed are fires set by indigenous peoples for land clearance; the existence of heavy-bodied herbivores; and that the pampas are relicts of drier past climates. These explanations have been criticised as mono-causal. "Overall, we expect that low propagule pressure, abiotic stresses, biotic resistance, and a paucity of specific symbionts might have exerted a synergistic influence in slowing tree invasion rates ".[11]

The World Wildlife Fund divides the Pampas into three distinct ecoregions. The Uruguayan Savanna lies east of the Paraná River, and includes all of Uruguay, most of Entre Ríos and Corrientes provinces in Argentina, and the southern portion of Brazil's state of Rio Grande do Sul. The Humid Pampas include eastern Buenos Aires Province, and southern Entre Ríos Province. The Semiarid Pampas includes western Buenos Aires Province and adjacent portions of Santa Fe, Córdoba, and La Pampa provinces. The Pampas are bounded by the drier Argentine Espinal grasslands, which form a semicircle around the north, west, and south of the Humid Pampas.

Winters are cold to mild, and summers are hot and humid. Rainfall is fairly uniform throughout the year but is a little heavier during the summer. Annual rainfall is heaviest near the coast and decreases gradually further inland. Rain during the late spring and summer usually arrives in the form of brief heavy showers and thunderstorms. More general rainfall occurs the remainder of the year as cold fronts and storm systems move through. Although cold spells during the winter often send nighttime temperatures below freezing, snow is quite rare. In most winters, a few light snowfalls occur over inland areas.

Central Argentina boasts a successful agricultural business, with crops grown on the Pampas south and west of Buenos Aires. Much of the area is also used for cattle, and more recently, to cultivate vineyards in the Buenos Aires wine region. The area is also used for farming honey using European honeybees. These farming regions are particularly susceptible to flooding during thunderstorms. The weather averages out to be 16 °C (60 °F) year-round in the Pampas.

Population

[edit]

Argentina

Argentina

Buenos Aires: 17,569,053

Buenos Aires: 17,569,053 Córdoba: 3,978,984

Córdoba: 3,978,984 Santa Fe: 3,556,522

Santa Fe: 3,556,522 Buenos Aires City: 3,120,612

Buenos Aires City: 3,120,612 Entre Ríos: 1,426,426

Entre Ríos: 1,426,426 La Pampa: 366,022

La Pampa: 366,022

Brazil

Brazil

Rio Grande do Sul: 10,882,965

Rio Grande do Sul: 10,882,965

Uruguay

Uruguay

- All departments: 3,444,263

- Total Population of the Pampas: 44,344,847

Immigration

[edit]

Starting in the 1840s but intensifying after the 1880s, European immigrants began to migrate to the Pampas, first as part of government-sponsored colonization schemes to settle the land and later as tenant farmers "working as either a sharecropper or as paid laborers for absentee landowners"[12] in an attempt to make a living for themselves.

However, many immigrants eventually moved to more permanent employment in cities, as industrialization picked up after the 1930s. As a result, Argentina's history of immigration in Buenos Aires Province is typically associated with cities and urban life, unlike in Entre Ríos Province and Santa Fe Province, where European immigration took on a more rural profile.

See also

[edit]- Dry Pampa

- Humid Pampas

- Estancia

- Federal University of Pampa

- Gaucho

- José Froilán González - the "Pampas Bull"

- Luis Ángel Firpo - the "Wild Bull of Las Pampas"

- Médanos (dunes)

- Médanos wines

- Riograndense Republic

- Southern Cone

- South American jaguar

References

[edit]- ^ Zipser, E. J.; C. Liu; D. J. Cecil; S. W. Nesbitt; D. P. Yorty (2006). "Where are the Most Intense Thunderstorms on Earth?" (PDF). Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 87 (8): 1057–1071. Bibcode:2006BAMS...87.1057Z. doi:10.1175/BAMS-87-8-1057. S2CID 51044775. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-08-06.

- ^ Virts, Katrina S.; J. M. Wallace; M. L. Hutchins; R. H. Holzworth (2013). "Highlights of a New Ground-Based, Hourly Global Lightning Climatology". Bull. Am. Meteorol. Soc. 94 (9): 1381–91. Bibcode:2013BAMS...94.1381V. doi:10.1175/BAMS-D-12-00082.1. S2CID 73647974.

- ^ Rasmussen, Kristen L.; M. D. Zuluaga; R. A. Houze Jr. (2014). "Severe convection and lightning in subtropical South America". Geophys. Res. Lett. 41 (20): 7359–66. Bibcode:2014GeoRL..41.7359R. doi:10.1002/2014GL061767.

- ^ Paula, R.C.; DeMatteo, K. (2016) [errata version of 2015 assessment]. "Chrysocyon brachyurus". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2015: e.T4819A88135664. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2015-4.RLTS.T4819A82316878.en. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ "Southern South America: Southeastern Argentina | Ecoregions | WWF". World Wildlife Fund. Retrieved 2020-02-20.

- ^ BirdLife International. (2016). "Athene cunicularia". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T22689353A93227732. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T22689353A93227732.en. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ "Southern South America: Eastern Argentina". World Wildlife Fund.

- ^ Bernal, N. (2016). "Dolichotis salinicola". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T6786A22190451. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T6786A22190451.en. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Black-Decima, P.A.; Vogliotti, A. (2016). "Mazama gouazoubira". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016: e.T29620A22154584. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-2.RLTS.T29620A22154584.en. Retrieved 27 March 2024.

- ^ Lopes, Renato Pereira; Pereira, Jamil Corrêa; Kerber, Leonardo; Dillenburg, Sérgio Rebello (August 2020). "The extinction of the Pleistocene megafauna in the Pampa of southern Brazil". Quaternary Science Reviews. 242: 106428. Bibcode:2020QSRv..24206428L. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2020.106428.

- ^ Chaneton, Enrique J.; Mazía, Noemí; Batista, William B.; Rolhauser, Andrés G.; Ghersa, Claudio M. (2012). "Woody Plant Invasions in Pampa Grasslands: A Biogeographical and Community Assembly Perspective". In Myster, Randall W. (ed.). Ecotones Between Forest and Grassland. Springer. doi:10.1007/978-1-4614-3797-0_5. ISBN 978-1-4614-3797-0. Retrieved 7 May 2024., pp. 122-7.

- ^ Meade, Teresa A. (2016). History of Modern Latin America: 1800 to the Present. Wiley Blackwell Concise History of the Modern World. Wiley. ISBN 978-1-118-77248-5.

External links

[edit]- Pampas

- Agriculture in Argentina

- Climate of Argentina

- Ecoregions of Argentina

- Ecoregions of Brazil

- Ecoregions of South America

- Environment of Rio Grande do Sul

- Grasslands of Argentina

- Grasslands of Brazil

- Grasslands of South America

- Grasslands of Uruguay

- Landforms of Buenos Aires Province

- Landforms of Córdoba Province, Argentina

- Landforms of Entre Ríos Province

- Landforms of La Pampa Province

- Landforms of Rio Grande do Sul

- Landforms of Santa Fe Province

- Landforms of Uruguay

- Natural history of Uruguay

- Natural regions of South America

- Neotropical ecoregions

- Physiographic provinces

- Plains of Argentina

- Plains of Brazil

- Plains of South America

- Quechua words and phrases

- Regions of Argentina

- Temperate grasslands, savannas, and shrublands