Ashdown Forest

| Ashdown Forest | |

|---|---|

Vanguard Way across Ashdown Forest | |

| Location | East Sussex, England |

| Coordinates | 51°04′21″N 0°02′35″E / 51.07250°N 0.04306°E |

| Governing body | The Conservators of Ashdown Forest |

| Website | www |

Ashdown Forest is an ancient area of open heathland occupying the highest sandy ridge-top of the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty. It is situated some 30 miles (48 km) south of London in the county of East Sussex, England. Rising to an elevation of 732 feet (223 m) above sea level, its heights provide expansive vistas across the heavily wooded hills of the Weald to the chalk escarpments of the North Downs and South Downs on the horizon.

Ashdown Forest's origins lie as a medieval hunting forest created soon after the Norman conquest of England. By 1283 the forest was fenced in by a 23 miles (37 km) pale enclosing an area of some 20 square miles (52 km2; 13,000 acres; 5,200 ha). Thirty-four gates and hatches in the pale, still remembered in place names such as Chuck Hatch and Chelwood Gate, allowed local people to enter to graze their livestock, collect firewood, and cut heather and bracken for animal bedding. The forest continued to be used by the monarchy and nobility for hunting into Tudor times, including notably Henry VIII, who had a hunting lodge at Bolebroke Castle, Hartfield and who courted Anne Boleyn at nearby Hever Castle.

Ashdown Forest has a rich archaeological heritage. It contains much evidence of prehistoric human activity, with the earliest evidence of human occupation dating back to 50,000 years ago. There are important Bronze Age, Iron Age, and Romano-British remains. The forest was the centre of a nationally important iron industry on two occasions, during the Roman occupation of Britain and in the Tudor period when, in 1496, England's first blast furnace was built at Newbridge, near Coleman's Hatch, marking the beginning of Britain's modern iron and steel industry. In 1693, more than half the forest was taken into private hands, with the remainder set aside as common land. The latter today covers 9.5 square miles (25 km2; 6,100 acres; 2,500 ha) and is the largest area with open public access in South East England. The ecological importance of Ashdown Forest's heathlands is reflected by its designation as a Site of Special Scientific Interest, as a Special Protection Area for birds, and as a Special Area of Conservation for its heathland habitats. It is part of the European Natura 2000 network as it hosts some of Europe's most threatened species and habitats.[1]

Ashdown Forest is famous for serving as inspiration for the Hundred Acre Wood, the setting for the Winnie-the-Pooh stories written by A. A. Milne.[2] Milne lived on the northern edge of the forest and took his son, Christopher Robin, walking there.[3] The artist E. H. Shepard drew on the landscapes of Ashdown Forest as inspiration for many of the illustrations he provided for the Pooh books.[4]

Settlements

[edit]Ashdown Forest notably lacks any significant settlements within the large boundary defined by its medieval pale. There are however a number of villages situated on the edge of the forest adjacent to the pale or close to it. These include Nutley, Fairwarp, Danehill and Maresfield to the south and Forest Row and Hartfield to the north. The town of Crowborough abuts the forest on its eastern side while the town of East Grinstead lies 3 miles (4.8 km) to the north-west.

Toponymy

[edit]Ashdown Forest does not seem to have existed as a distinct entity before the Norman Conquest of 1066, nor is it mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086. The area that was to become known as Ashdown Forest was merely an unidentified part of the Forest of Pevensel, a Norman creation within the Rape of Pevensey that had been carved out of a much larger area of woodland, the Weald, which itself was a part of the prehistoric forest cover of the British landmass, the British wildwood.[5] The first recorded reference to Ashdown Forest by name is in the period 1100–1130, when Henry I confirmed the right of monks to use a road across the forest of "Essessdone", a right which the monks claimed to have held since the Conquest.

"Ashdown Forest" consists of words from two different languages. The first word, Ashdown, is of Anglo-Saxon origin. It is probably derived from the personal name of an individual or people called Æsca, combined with dūn, Old English for hill or down, hence Æsca's dūn—the hill of Æsca.[6] It has no connection with ash trees, which have never been common given the soil conditions.

The second word, forest, is a term here used by the Normans to denote land that was subject to forest law, a harsh and much resented supplement to the common law that was designed to protect, for the king's benefit, the beasts of the chase, such as deer and wild boar, and the vegetation (the vert) that provided them with food and cover. Forest law prescribed severe penalties, particularly in the 11th and 12th centuries, for those who transgressed, and for a time it governed large parts of the English countryside, including entire counties such as Surrey and Essex. However, while forest land was legally set aside by the crown for hunting and protected its sovereign right to all wild animals, commoners were still able to exercise—within strict limits—many of their traditional or customary rights, for example, to pasture their swine in the woods or collect wind-blown branches and trees. Thus, in the 13th century, the commoners of Ashdown were recorded as grazing large numbers of swine and cattle on the forest alongside the many deer that were kept for aristocratic sport and the provision of venison.[7]

Note that forest does not have the modern meaning of "heavily wooded". Medieval hunting forests like Ashdown consisted of a mixture of heath, woodland and other habitats in which a variety of game could flourish, and where deer in particular could find both open pasture for browsing and woodland thickets for protective cover.

Shape and extent

[edit]

Ashdown Forest is shaped, roughly speaking, like an inverted triangle, some 7 miles (11 km) from east to west and the same distance from north to south.[8]

The boundary of the forest can be defined in various ways, but the most important is that given by the line of the medieval pale, which goes back to its origins as a hunting forest. The pale, first referred to in a document of 1283, consisted of a ditch and bank surmounted by an oak palisade. 23 miles (37 km) in length, it enclosed an area of some 20.5 square miles (5,300 ha). The original embankment and ditch, albeit now rather degraded and overgrown, can still be discerned in places today.

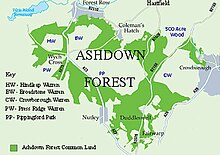

In 1693 the forest assumed its present-day shape when just over half its then 13,991 acres (5,662 ha) was assigned for private enclosure and improvement, while the remainder, about 6,400 acres (2,600 ha), was set aside as common land. Much of the latter was distributed in a rather fragmentary way around the periphery of the forest close to existing settlements and smallholdings (see map). Many present-day references to Ashdown Forest, including those made by the conservators, treat the forest as synonymous and co-terminous with this residual common land; this can lead to confusion: according to one authority "when people speak of Ashdown Forest, they may mean either a whole district of heaths and woodland that includes many private estates to which there is no public access, or they may be talking of the [common land] where the public are free to roam".[9]

Most of today's common land lies within the medieval pale, although one tract, near Chelwood Beacon, acquired quite recently by the forest conservators, extends outside. The conservators have acquired other tracts in recent years as suitable opportunities have arisen, for example at Chelwood Vachery, as part of a policy to extend the amount of land that they regulate and protect within the pale. According to the definition used by the conservators, which relates to the land for which they have statutory responsibility, the area of Ashdown Forest is 2,472 hectares (9.5 sq mi).

Geology

[edit]

The underlying geology of Ashdown Forest is mostly sandstone, predominantly the Lower Cretaceous Ashdown Formation. This forms a layer varying from 500 to 700 feet (150 to 210 m) thick, consists of fine-grained, silty interbedded sandstones and siltstones with subordinate amounts of shale and mudstone. It is the oldest Cretaceous geological formation that crops out in the Weald.[10]

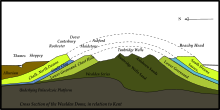

The Ashdown Formation has been exposed by the erosion, over many millions of years, of a geological dome, the Weald-Artois Anticline, a process which has left the dome's oldest layers, the resistant sandstones that form its central east–west axis, as a high forest ridge that includes Ashdown, St. Leonard's, and Worth forests. This forest ridge, the most prominent part of the High Weald, is surrounded by successive concentric bands of younger sandstones and clays, and finally chalk. These form hills or vales depending on their relative resistance to erosion. Consequently, what the viewer sees when looking north or south across the Weald from the heights of Ashdown Forest is a series of successively younger geological formations. These include heavily wooded lowlands formed on Weald Clay, the high Greensand Ridge escarpment that rises prominently to the north, and, on the horizon, the chalk escarpments of the North Downs and South Downs (see diagram, right).

The Ashdown Formation is the lowest (oldest) layer of the Hastings Beds, which comprise (in sequence) the Ashdown Formation, Wadhurst Clay Formation, and Tunbridge Wells Sand Formation,[11] and which are now thought to be predominantly fluvial flood-plain deposits.[12] The Hastings Beds in turn represent the oldest part of the series of Cretaceous geological formations that make up the Weald-Artois Anticline, comprising (in sequence, from oldest to youngest) the Hastings Beds, Weald Clay, Lower Greensand, Gault, Upper Greensand, and Chalk. The anticline, which stretches from South East England into northern France, and is breached by the English Channel, was created soon after the end of the Cretaceous period as a result of the Alpine orogeny. Ashdown Forest is itself situated on a local dome, the Crowborough Anticline.

Much of the iron ore that provided the raw material for the iron industry of Ashdown Forest was obtained from the Wadhurst Clay, which is sandwiched between the Ashdown Sands and Tunbridge Wells Sands (the latter encircles Ashdown Forest forming an extensive district of hilly, wooded countryside). Outcrops of Wadhurst Clay, which occurs as both nodules and in tabular masses, are distributed discontinuously in a horseshoe shape around Ashdown Forest, which has influenced the historical geography of iron-working around the forest.[13]

Like the rest of the Weald, Ashdown lay beyond the southern limits of Quaternary ice sheets, but the whole area was subject at times to a severe periglacial environment that has contributed to its geology and shaped its landforms.

Ecology

[edit]

Ashdown Forest is one of the largest single continuous blocks of lowland heath, semi-natural woodland and valley bog in south east England. Its geology is a major influence on its biology and ecology. The underlying sandstone geology of the Ashdown Sands, when combined with a local climate that is generally wetter, cooler and windier than the surrounding area owing to the forest's elevation, which rises from 200 feet (61 m) to over 700 feet (210 m) above sea level, gives rise to sandy, largely podzolic soils that are characteristically acid, clay, and nutrient-poor.[14] On these poor, infertile soils have developed heathland, valley mires and damp woodland. These conditions have never favoured cultivation and have been a barrier to agricultural improvement.

The forest predominantly consists of lowland heathland. Of the 2,472 ha of forest common land, 55% (1365 ha) is heathland while 40% (997 ha) is mixed woodland.[15] Lowland heathland is a particularly valuable but increasingly threatened habitat harbouring rare plant and animal species, which lends the forest importance at a European level. The survival of the forest's extensive heathlands has become all the more important when set against the large-scale loss of English lowland heathland over the last 200 years; within the county of East Sussex, heathland has shrunk by 50% over the last 200 years, and most of what remains is in Ashdown Forest.

Flora

[edit]Heathland

[edit]Ashdown Forest is noted for its heathland plants and flowers, such as the marsh gentian, but it also provides other distinctive or unusual plant habitats.

The extensive areas of dry heath are dominated by ling (Calluna vulgaris), bell heather (Erica cinerea) and dwarf gorse (Ulex minor). Important lichen communities include Pycnothelia papillaria. Common bracken (Pteridium aquilinum) is dominant over large areas. On the damper heath, cross-leaved heath (Erica tetralix) becomes dominant with deer-grass (Trichophorum cespitosum. The heath and bracken communities form a mosaic with acid grassland dominated by purple moor-grass (Molinia caerulea) mingled with many specialised heathland plants such as petty whin (Genista anglica), creeping willow (Salicaceae sp.) and heath spotted orchid (Dactylorhiza maculata).

In the wet areas are found several species of sphagnum moss together with bog asphodel (Narthecium ossifragum), common cotton-grass (Eriophorum angustifolium) and specialities such as marsh gentian (Gentiana pneumonanthe), ivy-leaved bell flower (Wahlenbergia hederacea), white-beaked sedge (Rhynchospora alba) and marsh club moss (Lycopodiella inundata). The marsh gentian, noted for its bright blue trumpet-like flowers, has a flowering season lasting from July well into October and is found in about a dozen colonies.

Gorse (Ulex europaeus), silver birch (Betula pendula), pedunculate oak (Quercus robur) and Scots pine (Pinus sylvestris) are scattered across the heath, in places forming extensive areas of secondary woodland and scrub. Older woodlands consist of beech (Fagus sylvatica) and sweet chestnut (Castanea sativa). These contain bluebell (Hyacinthinoides non-scripta), bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus), hard fern (Blechnum spicant) and honeysuckle (Lonicera periclymenum) with birds-nest orchid (Neottia nidus-avis) and violet helleborine (Epipactis purpurata) found particularly under beech. In the woodlands can also be found wood anemone (Anemone nemorosa) and common wood sorrel (Oxalis acetosella).

Streams and ponds

[edit]Forest streams, often lined by alder trees such as Alnus glutinosa, and grey sallow Salix cinerea, birch and oak, cut through the soft sandstone forming steep-sided valleys (ghylls) that are sheltered from winter frosts and remain humid in summer, creating conditions more familiar in the Atlantic-facing western coastal regions of Britain. Uncommon bryophytes such as the liverwort Nardia compressa and a range of ferns including the mountain fern Oreopteris limbosperma and the hay-scented buckler fern Dryopteris aemula thrive in this “Atlantic” microclimate.

The damming of streams, digging for marl, and quarrying have produced several large ponds containing, particularly in former marl pits, localised rafts of broad-leaved pondweed Potamogeton natans, beds of bulrush (reedmace) Typha latifolia and water horsetail Equisetum fluviatile.

Woodland

[edit]Woodland covers nearly 1,000 hectares (2,500 acres) of the forest, 40% of its area[16] Most of the woodland on the common land of the forest is young and contains few older trees; there is little ancient woodland, defined as woodland that has been continuously wooded since 1600. Almost all the latter that exists within the medieval forest pale is found on land that was set aside in the 1693 division of the forest for private ownership and exploitation.[17] Some wooded ghylls however do contain older trees and there are a few individual old trees, especially beech, that mark former boundaries.

The two most common forms of forest woodland are oak woods on acid brown earth soils, including hazel and chestnut coppice (62% of the total woodland area), and birch woods with oak in degenerating heathlands (27%). Alder trees growing in wet and waterlogged peaty soils account for about 1% of the woodland, while birch and willow trees growing in wet areas each account for less than 1%. Beechwoods growing on acid brown earth soils account for another 3%.[18]

The clumps of Scots pine that form such a distinctive, iconic hilltop feature of Ashdown Forest were first planted in 1816 by the Lord of the Manor to provide habitats for blackgame. 20th-century plantings comprise Macmillan Clump near Chelwood Gate (commemorating former British prime-minister Harold Macmillan, who lived at Birch Grove, on the edge of the forest at Chelwood Gate), Kennedy Clump (commemorating a visit to the area by John F. Kennedy, when he stayed with Macmillan), Millennium Clump and Friends Clump, planted in 1973 to mark the Year of the Tree.

Fauna

[edit]Birds

[edit]Important populations of heath and woodland birds are found on the forest, notably Dartford warbler Sylvia undata (the forest has all-year resident populations of this, Britain's scarcest heathland bird species, which has seen a resurgence since the early 1990s) and European nightjar Caprimulgus europaeus. Because of this, it has been designated as a Special Protection Area and it is a popular destination for bird-watchers.

The forest contains four main bird habitats:[19]

- Open lowland heath, with various species of gorse and heather: Dartford warbler (Sylvia undata), stonechat (Saxicola rubecola) and meadow pipit (Anthus trivialis); in the summer, Eurasian skylark (Alauda arvensis), common linnet (Carduelis cannabina), yellowhammer (Emberiza citrinella) and common cuckoo (Cuculus canorus); and in winter, rarely, hen harrier (Circus cyaneus).

- Open areas of grassland, heather or gorse, with some bogs, interspersed with single trees or clumps of trees, particularly Scots pine: lesser redpoll (Carduelis cabaret), goldcrest (Regulus regulus); in the summer, woodlark (Lullula arborea), tree pipit (Anthus sylvestris), nightjar (Caprimulgus europaeus), common redstart (Phoenicurus phoenicurus), spotted flycatcher (Muscicapa striata), common snipe (Gallinago gallinago), Eurasian hobby (Falco subbuteo), Eurasian woodcock (Scolopax rusticola), and yellowhammer; in spring and autumn, northern wheatear (Oenanthe oenanthe), whinchat (Saxicola rubetra), common crossbill (Loxia curvirostra); and in winter, rarely, great grey shrike (Lanius exubitor).

- Scrub areas, especially on the boundary between woodland and heath/grassland: common reed bunting (Emberiza schoeniclus); in the summer, turtle dove (Streptopelia turtur); in winter, Eurasian siskin Carduelis spinus and lesser redpoll (Acanthis cabaret).

- Mixed woodlands of oak, birch and sweet chestnut, often with Scots pine: stock dove (Columba oenas), marsh tit (Parus palustris), tawny owl (Strix aluco), Eurasian bullfinch (Pyrrhula pyrrhula) and Eurasian sparrowhawk (Accipiter nisus); in the summer common firecrest (Regulus ignicapillus); common buzzard (Buteo buteo) (occasional visitor).

Insects

[edit]The forest supports a rich invertebrate fauna, with many heathland specialities. Half of Britain's 46 breeding species of damselflies and dragonflies (the Odonata) have been recorded, the scarcer among them being the black darter, brilliant emerald and small red damselfly. It is also an important home for the golden-ringed dragonfly, which flies from mid-June to early September. Of the forest's 34 species of butterfly, the most spectacular, the purple emperor, can be hard to see. Another speciality, the silver-studded blue, is by contrast plentiful, with the main food plants of its caterpillars being gorses and heathers.

Deer

[edit]Deer have been a major feature of Ashdown Forest, at least since its days as a medieval hunting forest. Red deer (Cervus elaphus), an integral part of Wealden culture since as far back as 6,000-8,000 years ago, and fallow deer (Dama dama)—brought by the Romans from mainland Europe—, present in Sussex in the Romano-British era and particularly favoured by the Normans for hunting, were both commonly hunted in the forest until the 17th century; around that time, the red deer had disappeared completely from the forest while fallow deer numbers had sharply declined. The depletion of the woodlands (which provided deer with cover), the deterioration of the forest pale (which allowed them to escape) and the depredations of poachers were all factors in their decline.

Fallow deer returned in the 20th century, probably escapees from the Sackville estate, Buckhurst Park. The population roaming the forest has grown sharply in the last three decades, in-common with deer herds elsewhere in England, and they now number in their thousands. Also present are roe deer (Capreolus capreolus), the only native deer still roaming the forest, and two recently-introduced Asian species, the "barking deer", or muntjac (Muntiacus muntjak), and the sika (Cervus nippon).

Many deer are involved in collisions with motor vehicles on local roads, especially as they move around the forest to feed at dawn and dusk, and many are killed. In 2009, forest rangers dealt with 244 deer casualties, compared with 266 the year before; however, this is likely to be a significantly low estimate, as the rangers cannot deal with all the accidents that occur. The forest conservators have identified a need to reduce the deer population and have begun working with neighbouring private landowners on measures to cull them.[20]

Exmoor ponies

[edit]Exmoor ponies graze on the Ashdown Forest to help tackle a variety of fast-growing botanical species,[21] and thus keep the heathland[22] habitat balanced by preventing scrub encroachment. The Exmoor ponies are not truly domesticated; rather, they are managed by the Ashdown Forest which keeps them enclosed within large areas.

Landscape of Ashdown Forest

[edit]

Ashdown Forest's landscape in the early 19th century was famously described by William Cobbett:[23]

At about three miles (4.8 km) from Grinstead you come to a pretty village, called Forest-Row, and then, on the road to Uckfield, you cross Ashurst [sic] Forest, which is a heath, with here and there a few birch scrubs upon it, verily the most villainously ugly spot I saw in England. This lasts you for five miles (8.0 km), getting, if possible, uglier and uglier all the way, till, at last, as if barren soil, nasty spewy gravel, heath and even that stunted, were not enough, you see some rising spots, which instead of trees, present you with black, ragged, hideous rocks.

The predominantly open, heathland landscape of Ashdown Forest described so vividly by Cobbett in 1822 and later immortalised by E.H. Shepard in his illustrations for the Winnie-the-Pooh stories is essentially man-made: in the absence of human intervention, heathlands such as Ashdown's are quickly taken over by scrub and trees. Ashdown's heathlands date back to medieval times, and quite possibly earlier.[24] Two elements were important in shaping this landscape: the local population of commoners, who exploited the forest's resources over many centuries; and the iron industry of the forest, which flourished in the 16th century.

The commoners played an important role in maintaining the forest as a predominantly heathland area by exercising their rights of common to exploit its resources in a variety of ways: by grazing livestock such as pigs and cattle, which suppressed the growth of trees and scrub; by cutting trees for firewood and for other uses; by cutting dead bracken, fern and heather for use as bedding for their livestock in winter; by periodically burning areas of heathland to maintain pasture; and so on. At times, the numbers of livestock being grazed on the forest was very large: at the end of the 13th century the commoners were turning out 2,000-3,000 cattle, alongside the 1,000-2,000 deer that were also present,[25] while according to a 1293 record the forest was being grazed by more than 2,700 swine.[26]

A second important factor was the heavy depletion of the forest's woodlands by the local iron industry, which grew very rapidly in the late 15th and 16th centuries, following the introduction of the blast furnace in the 1490s, which led to a huge demand for charcoal. For example, large-scale tree cutting took place in the south of the forest to feed the iron works of the cannon maker Ralph Hogge. The loss of trees caused such concern for the Crown that as early as 1520 it was lamented that "much of the King's woods were cut down and coled [turned into charcoal] for the iron mills, and the forest digged for Irne [iron] by which man and beast be in jeopardy".[27] This ravaging of the forest's woodlands was later mitigated by the adoption of coppice management for the provision of sustainable supplies of charcoal. The impact of the industry on the forest, although significant, was however ultimately short-lived, as it died out in the 17th century.

Conservation measures

[edit]

The open heathland landscape of Ashdown Forest described by Cobbett in the 1820s and depicted by Shepard in the 1920s changed dramatically soon after the end of World War II when the commoners' exploitation of the forest - exercising their rights of common to graze livestock, cut bracken, etc. - declined to very low levels. The result was a regeneration of woodland and the loss of heathland: the proportion of heathland in the forest fell from 90% in 1947 to 60% in 2007. The forest conservators have now committed to maintaining the proportion of heathland at 60% and to returning it to 'favourable' condition.[28] Their efforts are being funded under a ten-year Higher Level Stewardship (HLS) agreement with Natural England; signed in August 2006, it is the largest such scheme in South East England.

The conservators have taken various steps to prevent natural regeneration of woodland. Regular mowing of bracken is carried out: an area of 266 ha out of the 400 ha on the forest has been mown twice a year since 2000. Large areas of the highly invasive Rhododendron ponticum have been cleared, initially funded by the Forestry Commission, and now carried on by local volunteers. Birch and other tree saplings are cut down in the winter.

The conservators have taken steps to promote livestock grazing on the forest as part of their heathland management policy. Grazing is considered to be a cheaper and more effective way of restoring and maintaining heathland than the use of mowing machinery. Sheep (which are a recent introduction to the forest, having only become 'commonable' since 1900[29]) are particularly useful because they graze scrub and in places that are difficult to mow. In 1996 the Secretary of State for the Environment gave permission for a 550 hectares (1,400 acres) fenced enclosure, representing about one-third of the forest's 1,500 ha of heathland, to be created in the south and west chases to allow commoners to graze their livestock in safety.

The enclosure of the common lands of the forest with fencing to enable grazing was and remains somewhat controversial with some members of the public. Exploring alternatives to enclosure, the conservators undertook a close-shepherded grazing pilot project from 2007 to 2010 with funding from the HLS scheme. A flock of Hebridean sheep, ultimately 300 in number, was guided by a shepherd and an assistant to graze unenclosed areas of the forest heathland. Among the advantages of this approach were that no fencing was required and grazing could be targeted on the most overgrown areas; among the disadvantages were its high labour intensity, high costs and low impact. The conservators have now begun using temporary electric fencing, which can be moved around to isolate different parts of the heathland, to enable the flock to graze without requiring close supervision by a shepherd.

Statutory designations

[edit]Ashdown Forest is an area of European ecological importance. It is designated by the UK government as a Site of Special Scientific Interest (SSSI),[30][31] a Special Protection Area (SPA),[32] a Special Area of Conservation (SAC)[33] and a Nature Conservation Review site.[34] It lies within the High Weald Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty.[1] An area of 103 hectares is Old Lodge Local Nature Reserve,[35] most of which is managed by the Sussex Wildlife Trust.[36]

Though not a statutory designation, Ashdown Forest forms part of the Western Ouse Streams and Ashdown Forest Biodiversity Opportunity Area, and is thus a subject of the Sussex Biodiversity Action Plan, which aims to focus conservation bodies, local government and statutory agencies on work to conserve and enhance the habitats and species of Sussex.[37]

The areas covered by the statutory designations are not identical to and are generally larger than the area of forest administered by the conservators. The SSSI covers 3,144 hectares (12.1 sq mi), mainly because, in addition to the forest land covered by the conservators, it also includes the Ministry of Defence's Pippingford Park Dry Training Area, accounting for 11% (346 hectares (1.3 sq mi)) of the SSSI, Hindleap Warren, Broadstone Warren and Old Lodge, which covers 76 hectares (0.3 sq mi). The SPA covers 3,207 hectares (12.4 sq mi) while the SAC covers 2,729 hectares (10.5 sq mi).

Recreation and leisure

[edit]

Ashdown Forest is the largest public access space in south east England, and the largest area of open, uncultivated countryside. A 2008 visitor survey estimated that at least 1.35 million visits are made each year. The most common reason given for visiting the forest was its "openness". Most visitors (85%) coming by car travelled 10 km or less and there were 62 dogs for every 100 visitors.[25]

Despite such large numbers of visitors, the forest has retained its celebrated tranquillity and sense of openness. The commons are freely open to the public, who are attracted by the large, elevated expanse of unspoiled heaths and woodlands where they may walk, picnic or simply sit while taking in the glorious views. Various bye-laws passed by the conservators help protect the forest environment for the public good, prohibiting such activities as, for example, mountain biking, off-road driving of motor vehicles, camping and the lighting of fires.

Travelling to Ashdown Forest

[edit]Most visitors come by car, and access is straightforward. The forest is crossed by a major road, the A22, which provides access from the M25 and M23 motorways. There are over 40 car parks across the forest to discourage drivers from parking their vehicles on roadsides.[38] In January 2022 the Conservators announced the findings of a public consultation and then voted to introduce car parking charges to the forest for the first time [39] The nearest railway station is at East Grinstead, which receives frequent train services from London.[40] The railway stations at Tunbridge Wells, Eridge, Crowborough and Uckfield are also nearby.[41] Two bus services cross the forest, the 261 service from East Grinstead railway station to Uckfield and the 270 service from East Grinstead railway station to Haywards Heath.[42] London Gatwick Airport is about 30 minutes away by car, and London Heathrow Airport is around 1 hour away by car.[41]

Visitor information

[edit]The Ashdown Forest Centre is the main visitor centre for the forest. The forest's principal tourism organisation is the Ashdown Forest Tourism Association.[43]

Recreational, sports and leisure activities

[edit]Ashdown Forest is very popular with walkers. Two long-distance footpaths, the Vanguard Way and Wealdway cross the forest and meet near Old Lodge. The Wealdway passes through Five Hundred Acre Wood, the Hundred Acre Wood of the Winnie-the-Pooh stories. The Ashdown Forest Centre produces a series of leaflets detailing walks in various parts of the forest, which may also be downloaded from its website.[44]

There are 82 miles (132 km) of tracks on the forest that may be ridden by horse once an annual permit has been obtained from the conservators. The main horse-riding organisation is the Ashdown Forest Riding Association, which has around 200 members.[45]

The forest, with its attractive landscapes, vistas and hills, is a popular destination for road cyclists, races and cyclosportives such as the Hell of the Ashdown.[46] Former Tour de France rider Sean Yates lives at Forest Row and has taken Lance Armstrong training here. Off-road cycling and mountain biking is prohibited for environmental reasons, except along public bridleways. A local pressure group is campaigning for this ban to be lifted.[47]

The Royal Ashdown Forest Golf Club occupies a large area of leasehold land in the northern part of the forest near Forest Row. It is a traditional members' club founded in 1888 at the instigation of Earl De La Warr, lord of the manor, who became its first president. Its two 18-hole heathland courses are notable for the absence of bunkers (at the insistence of the conservators). As elsewhere in Ashdown Forest, trees and bracken scrub have invaded following the cessation of grazing and decreased wood cutting by the commoners, and the club is working with the conservators to restore the golf courses to their original heathland character.[48]

The principal hotel within the forest is the Ashdown Park Hotel & Country Club, a listed 19th-century mansion house set in 186 acres (0.75 km2).[49]

Visitor attractions

[edit]The Ashdown Forest Centre

[edit]

The Ashdown Forest Centre, situated opposite Ashdown Park Hotel between Wych Cross and Coleman's Hatch, houses a visitor centre and is the administrative base for the Board of Conservators of Ashdown Forest. Completed in 1983, it consists of three old reconstructed barns. The visitor centre[50] has a permanent display about the forest's history and wildlife, details of walks in the forest and much other useful information for visitors, and an exhibition area for local craft and art work. It is open 7 days a week during the summer, weekends in the winter, and on bank holidays except Christmas Day and Boxing Day.

Vachery Forest Garden

[edit]Landscaped in 1925 by Col. Gavin Jones for F.J. Nettlefold, this 'lost' forest garden is situated in a remote, secluded steep-sided valley near Wych Cross. It was acquired by the conservators in 1994 and is now undergoing restoration. Already uncovered are a 250 metre gorge constructed using limestone brought from Cheddar Gorge, many unusual trees and a string of small lakes connected by sluices and weirs. The garden, which is open to the public, is part of Chelwood Vachery, a medieval estate dating back to at least 1229, and whose name may come from the French vache, referring to the grazing of cattle here by Michelham Priory. A leaflet describing a walk through Chelwood Vachery is available from the Ashdown Forest Centre. The nearest car-park is Trees on the A22 road between Wych Cross and Nutley.

Old Lodge Nature Reserve

[edit]Old Lodge Nature Reserve,[51] managed by Sussex Wildlife Trust, offers open vistas of the forest's heathland. A well-marked nature trail leads round most of the hilly 76 hectare reserve, which contains acidic ponds and areas of pine woodland. The reserve is notable for dragonfly, nightjar, redstart, woodcock, tree pipit, stonechat and adder. It has been designated a Local Nature Reserve.[52][53]

Nutley Windmill

[edit]

Nutley Windmill, which stands just north of the Nutley to Duddleswell road, is thought to be about 300 years old and is a rare example of an open-trestle post mill (the whole body of the mill can be rotated on its central post to face the wind). It has been restored to full working order and is open to the public. It is within easy walking distance of Friend's Clump car-park.

The Airman's Grave

[edit]

The Airman's Grave is not in fact a grave, but a memorial to the six man crew of a Wellington bomber of 142 Squadron who were killed when it crashed in the forest on the morning of 31 July 1941 on its return from a raid on Cologne during World War II. The memorial, which is a simple stone-walled enclosure on the heathland west of Duddleswell, shelters a white cross surrounded by a tiny garden of remembrance and was erected by the mother of Sergeant P.V.R. Sutton, who was aged 24 at the time of his death. A short public service takes place each year on Remembrance Sunday when a wreath is laid by an Ashdown Forest Ranger, at the request of Mrs Sutton, together with one from the Ashdown Forest Riding Association. The Ashdown Forest Centre has published a circular walk to the memorial, starting from Hollies car park.

Newbridge Furnace

[edit]At the foot of Kidd's Hill, in woods lying west of the road from Coleman's Hatch to Gills Lap, are the largely grassed-over remains of a 15th-century ironworks that mark the beginnings of Britain's modern iron and steel industry. A dedication placed at the site by the Wealden Iron Research Group reads: "Newbridge Furnace. At the behest of King Henry VII, the first English blast furnace, for the smelting of iron, was established in this place. 13 December A.D. 1496. Here, the water from the pond, held back by the dam or bay, gave power to the bellows of the furnace to make cast iron; and to a finery where the 'great water hammer' enabled immigrant French workers to forge bars of wrought iron. The works had a modest output, which cannot have exceeded 150 tons of iron a year. Early products included the ironwork of gun carriages for a military campaign in Scotland, and were soon to number guns and shot as well. From small beginnings, in this secluded corner of Sussex, grew the ironworks of the Weald, and subsequently the iron and steel industry throughout Great Britain."[54]

The forest pale

[edit]

Possibly as early as the 13th century, Ashdown Forest was enclosed as a hunting park, mainly for deer, by a 24-mile (39 km) long pale. This consisted of an earth bank 4–5 feet high surmounted by an oak paling fence with a deep ditch on the forest side that allowed deer to enter but not to leave. It enclosed an area of over 20½ square miles (5,300 hectares).[1] Entry was via 34 gates and hatches, gates being used for access by wheeled vehicles, commoners' animals and mounted groups, hatches by pedestrians. These names survive in local place-names such as Chuck Hatch and Chelwood Gate. Some of these entrances were, and still are, marked by pubs, for example the 18th-century Hatch Inn[55] at Coleman's Hatch, which occupies three former cottages believed to date to 1430 that later may have housed ironworkers from the nearby blast furnace at Newbridge.

It is not known precisely when the pale was built. Forest management accounts of 1283 refer to the cost of repairing the pale and building new lengths.[56] However, the granting of the "Free-chase of Ashdon" to John of Gaunt in 1372 and its renaming as Lancaster Great Park (see below) implies that the forest may only have been recently enclosed (chase denoted an open hunting ground, park an enclosed one).

The condition of the forest pale seems to have deteriorated significantly during the Tudor period. This coincided with, and may be partly linked to, the rapid growth under the Tudors of the local iron-making industry with its huge demand for raw materials in and around Ashdown Forest, such as charcoal and ironstone. This ultimately led to an appeal to King James, soon after his accession to the throne, for Ashdown's forest fences to be repaired in order to preserve the king's game. However, the pale seems to have fallen into almost complete disrepair by the end of the 17th century.

The bank and ditch associated with the pale are still visible in places around Ashdown Forest today, for example at Legsheath and adjacent to the car-park for Poohsticks Bridge on Chuck Hatch Lane.

A survey and research of the Pale of Ashdown Forest was undertaken as part of the Historic Environment Awareness Project, run by East Sussex County Council's Archaeology team, over 2011/2012 and the final report was published online.[57]

Winnie-the-Pooh

[edit]

Ashdown Forest is famous as the setting for the Winnie-the-Pooh stories, written by A. A. Milne.[2][4] The first book, Winnie-the-Pooh, was published in 1926 with illustrations by E. H. Shepard. The second book, The House at Pooh Corner, also illustrated by Shepard, was published in 1928. These hugely popular stories were set in and inspired by Ashdown Forest.[2][3][4]

Alan Milne, a writer who was born and lived in London, bought a country retreat for himself and his family at Cotchford Farm, near Hartfield, East Sussex, in 1925. This old farmhouse was situated on the banks of a tributary of the River Medway and lay just beyond the northern boundary of Ashdown Forest, about a mile from the ancient forest entrance at Chuck Hatch. The family would stay at Cotchford Farm at weekends and in the Easter and summer holidays. It was easy to walk from the farmhouse up onto the forest, and these walks were frequently family occasions which would see Milne, his wife, Daphne, his son, Christopher Robin, and his son's nanny, Olive, going "in single file threading the narrow paths that run through the heather".[58] Christopher, who was an only child born in 1920 and whose closest childhood relationship was with his nanny, spent his early years happily exploring the forest. It is the Ashdown Forest landscape, and Christopher's reports of his experiences and discoveries there, that provided inspiration and material for A.A. Milne's stories. As Christopher Milne wrote later: "Anyone who has read the stories knows the forest and doesn't need me to describe it. Pooh’s Forest and Ashdown Forest are identical".[59]

Several of the sites described in the books can be easily identified, although their names have been changed. For example, Five Hundred Acre Wood, which is a dense beech wood that was originally sold off from the forest in 1678 and is today privately owned, and which Christopher would sometimes walk through to reach the forest, became Hundred Acre Wood. The hilltop of Gills Lap, crowned by pine trees and visible from miles around, became Galleon's Lap. The North Pole and Gloomy Place are in Wren’s Warren Valley, a short walk north-east of Gill's Lap, as is The Dark and Mysterious Forest.

Furthermore, the landscapes depicted in Shepard’s illustrations for the Winnie-the-Pooh stories, which are very evocative of Ashdown Forest, can in many cases be matched up to actual views, allowing for a degree of artistic licence. Shepard's sketches of pine trees and other forest scenes are now exhibited at the V&A Museum in London.

A free leaflet, “Pooh Walks from Gill's Lap”, which is available from the Ashdown Forest Centre and downloadable from its website, describes a walk that takes in many locations familiar from the Pooh stories including Galleon's Lap, The Enchanted Place, the Heffalump Trap and Lone Pine, North Pole, 100 Aker Wood and Eeyore’s Sad and Gloomy Place.

A memorial plaque to Milne and Shepard can be found at Gill's Lap. Its heading is a quotation from the Pooh stories: "...and by and by they came to an enchanted place on the very top of the forest called Galleons Lap". The dedication reads: "Here at Gill's Lap are commemorated A. A. Milne 1882-1956 and E.H. Shepard 1879-1976 who collaborated in the creation of "Winnie-the-Pooh" and so captured the magic of Ashdown Forest and gave it to the world".

Poohsticks Bridge, which is open to the public, lies outside the forest on the northern edge of Posingford Wood, near Chuck Hatch. A path leads to the bridge from a car-park on Chuck Hatch Lane, just off the B2026 Maresfield to Hartfield road. The original bridge was built in 1907, restored in 1979 and completely rebuilt in 1999. So popular is the game of Poohsticks that the surrounding area has been denuded of twigs and small branches by the many visitors.[citation needed]

Pooh Corner, situated on the High Street in Hartfield village, sells Winnie-the-Pooh related products and offers information for visitors.[60]

History

[edit]Brief history

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (May 2021) |

Ashdown Forest came into existence as a Norman deer hunting forest in the period following the Norman Conquest of 1066.

At the highest points of the Ashdown Forest are the remains of several Barrow Mounds dated by the University of Sussex to the late Iron Age. At the nearby Pippingford Army Training Area there is a large hilltop settlement mound that is a Class A Listed Protection Ancient Monument site. The site includes Iron Age stock and hunting enclosures with recent finds of leaf-cut flint arrow heads dated to the middle Bronze Age period now on display in the East Grinstead Museum. (2013). The Hilltop hunting settlement is thought to have been constructed by the local Wealden Chieftain named Crugh who was gifted lands by his High Wealden Chieftain Uncle who lived at Marks Cross in East Sussex.[61]

Prior to the conquest, Ashdown seems simply to have been an unnamed part of the vast, sparsely populated, and in places dense and impenetrable woodland known to the Anglo-Saxons as Andredes weald ("the forest of Andred"), from which the present-day Weald derives its name. The Weald, of which Ashdown Forest is the largest remaining part, stretched for 30 miles (48 km) between the chalk escarpments of the North and South Downs and for over 90 miles (140 km) from east to west from Kent into Hampshire.[62]

Ashdown Forest is not mentioned in the Domesday Book of 1086 but, as part of the forest of Pevensel, the sub-division of the Weald that the Normans created within the Rape of Pevensey, it had already been granted by William the Conqueror to his half-brother Robert, Count of Mortain. This rape was strategically and economically important, extending as it did inland northwards from the English Channel coast towards London, and was guarded, as was the case with the other six Sussex rapes, by a castle. It was awarded to Robert, along with several hundred manors across England, in recognition of his support for William during the Norman conquest of England. Two important conditions applied to a forest like Pevensel: the king could keep and hunt deer there, while the commoners – tenant farmers who had smallholdings near the forest – could continue to graze their livestock there and cut wood for fuel and bracken for livestock bedding.

1095 – death of Robert de Mortain. Ashdown is then held by the lords of Pevensey Castle – a succession of high status members of the Norman and Plantagenet aristocracy, including several queens of England – for most of the next 200 years.

1100–1130 – Ashdown Forest is first referred to by name when Henry I confirms that monks can continue to use a road across the forest of "Essendone". The monks' claim that they have held the right since the Conquest implies the area was known by this name at least as far back as then.[63]

1268 – in the reign of Henry III, Ashdown Forest is vested in the Crown in perpetuity. The forest was subsequently used for deer hunting by Edward II, who built a hunting lodge near Nutley that was later to be used by John of Gaunt.

1282 – first documentary references to the forest pales appear in accounts prepared by a ranger recording the costs of timber that have been cut;[64]

1372 – Edward III grants the "Free-chase of Ashdon" to his third son, John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster.[65] It becomes known as Lancaster Great Park. The park then reverts to the Crown along with the rest of the Duchy of Lancaster after John of Gaunt's death in 1399. But for the next 300 years, until 1672, the forest is still referred to as Lancaster Great Park.

1662 – Lancaster Great Park is disafforested by Charles II, giving free rein to the Earl of Bristol to make 'improvements'.

1693 – Ashdown Forest (the former Lancaster Great Park) is divided up, and it assumes its present-day shape. Just over half of it – in portions of widely varying sizes, but with the largest ones tending to be located towards the centre of the forest – is allotted for 'inclosure and improvement' by private interests. The rest is retained as common land for use by those local landowners and tenants who possess rights of common.

1881 – the commoners of Ashdown Forest reach a successful conclusion to their defence of a lawsuit brought by the Lord of the Manor which contested the nature and extent of their rights of common on the forest (known as the "Great Ashdown Forest Case").

1885 – the Commons Regulation (Ashdown Forest) Provisional Order Confirmation Act 1885 introduces bye-laws to regulate and protect the forest, and a Board of Conservators is established.

1984 – a significant part of the forest was set a blaze by a local school boy, Anthony Martin. Eight fire engines were called to the scene and the fire was controlled.[citation needed]

1988 – the freehold of the forest is acquired by East Sussex County Council from the executors of the Lord of the Manor, forestalling the possibility that the remaining common land of the forest would be broken up and sold off into private hands.

The 1693 division of Ashdown Forest

[edit]During the 17th century, under both the Stuart monarchy and during the Interregnum, there were repeated proposals to inclose (enclose) and develop the forest. Under James I and Charles I parcels of land were sold off piecemeal. During the Interregnum the condition of the forest deteriorated so much that by the time of the Restoration, in 1660, it was in a state where "the whole forest [is] laid open and made waste".[66] Attempts to enclose and improve the forest (for example, by introducing rabbit farming, or sowing crops) were however strongly opposed throughout by the local commoners, who claimed rights of common on the forest, having exercised them "from time out of mind", as well as by neighbouring estates who claimed right of pasture there.

In 1662 the forest was granted to one of Charles II's closest allies, George Digby, Earl of Bristol, and it was formally disafforested to allow Bristol a free hand to improve it. His attempts to do so were however frustrated "by the crossness of the neighbourhood";[67] the fences he erected were thrown down and the crops he sowed were trampled by cattle. He defaulted on his rental payments to the Crown and left. Subsequent Lords of the Manor suffered similar opposition from the commoners. Compromise proposals were made to divide up the forest that would leave sufficient common land to meet the needs of commoners, while giving the rest up for improvement.

These unresolved tensions came to a head when, in 1689, a major landowner and 'Master of the Forest', Charles Sackville, 6th Earl of Dorset, brought a legal suit against 133 commoners in the court of the Duchy of Lancaster. The court decided to appoint commissioners to divide up Ashdown Forest's 13,991 acres (5,662 ha) in a way that would meet the needs of both defendants and plaintiffs. The commissioners made their award on 9 July 1693. They set aside 6,400 acres (2,600 ha), mostly in the vicinity of farms and villages, as common land, where the commoners were granted sole right of pasturage and the right to cut birch, alder and willow (but no other trees). The commoners were however excluded forever from the rest of the forest, about 55 per cent of its area, which was assigned for "inclosure and improvement" (though substantial areas had already been enclosed by then, so in such cases the decree was merely confirming the status quo).

The land award of 1693 is largely responsible for shaping the map of Ashdown Forest today. The common land is highly fragmented and irregular in shape, broken up by many private enclosures, large and small. It tends to lie on the periphery of the forest near existing settlements. Some of the largest enclosures, such as Hindleap Warren, Prestridge Warren, Broadstone Warren and Crowborough Warren, mostly lying towards the centre of the forest, were used for a time for intensive rabbit farming. Some of these enclosures have today acquired interesting uses: Pippingford Park, in the very centre of the forest, occupied by the army in 1939 as a defence against Operation Sea Lion, remains an important military training area,[68] Broadstone Warren is a scout camp and activity centre,[69] while Hindleap Warren is an outdoor education centre.[70]

Although the 1693 land award envisaged enclosure and improvement for profitable gain, the land it allotted to private exploitation has in fact largely remained uncultivated; this has helped Ashdown Forest to retain the appearance of being an extensive area of wild country that is so valued today.[71] That said, there is nevertheless a visible contrast between the areas of common land, maintained by the conservators, which are predominantly heathland, and the extensive privately held lands, which are generally either quite heavily wooded or cleared for pasture.

The Great Ashdown Forest Case

[edit]In 1876-82 a renewed challenge to commoners' rights became known as the Great Ashdown Forest Case, one of the most famous legal disputes of Victorian England.

On 13 October 1877 John Miles was seen on the forest cutting litter (heather and bracken for livestock bedding and other uses) on behalf of Bernard Hale, his employer and the owner of a local estate, by a keeper, George Edwards. Edwards was a well-known and unpopular local man who was acting as the representative of the Lord of the Manor of Duddleswell, Reginald Sackville, 7th Earl De La Warr, who owned the land on which the forest stood. In a test case,[72][73] the Earl challenged the right of Hale to cut litter. Hale, who claimed ownership of his estate made him a commoner of the forest, argued that he was entitled to send his men onto the forest to cut and remove bracken, fern, heather and other plants. The Earl maintained that the commoners' rights of pasturage and herbage granted under the 1693 decree only entitled them to graze their animals on the commons.[71] At the end of a protracted and complicated legal case, the court ruled against the commoners, who included some of the wealthiest landowners in Sussex. They appealed, and their appeal was upheld in 1881, but only on one ground, that it had been a long-standing practice for commoners to cut and take away litter from the forest, and they were therefore entitled to continue to do so under the Prescription Act 1832.

Resolution of the case in favour of the commoners led directly to today's framework of forest governance, with the passing of the first Ashdown Forest Act in 1885 and the establishment of a board of conservators for the forest.

Formation of the Board of Conservators

[edit]| Commons Regulation (Ashdown Forest) Provisional Order Confirmation Act 1885 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act to confirm the Provisional Order for the Regulation of Ashdown Forest, situate in the parishes of East Grinstead, Hartfield, Withyham, Buxted, Maresfield, and Fletching, in the county of Sussex, in pursuance of a report of the Land Commissioners for England. |

| Citation | 48 & 49 Vict. c.lvi |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 16 July 1885 |

| Other legislation | |

| Amended by | Ashdown Forest Act 1949 |

Status: Amended | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

| Ashdown Forest Act 1937 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act to alter the constitution of the Conservators of Ashdown Forest to confer further powers upon the said Conservators and to provide for contributions towards their expenses by certain authorities and for other purposes. |

| Citation | 1 Edw. 8 & 1 Geo. 6. c. lii |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 1 July 1937 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Ashdown Forest Act 1974 |

Status: Repealed | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

| Ashdown Forest Act 1949 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act to provide for the vesting in the Secretary of State for War of certain lands in the county of Sussex forming part of Ashdown Forest and for the acquisition and addition to the forest of other lands in exchange therefor to make provision for the use of the forest for the purposes of military training and for other purposes. |

| Citation | 12, 13 & 14 Geo. 6. c. xlvii |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 30 July 1949 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repealed by | Ashdown Forest Act 1974 |

Status: Repealed | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

| Ashdown Forest Act 1974 | |

|---|---|

| Act of Parliament | |

| |

| Long title | An Act to alter the constitution of, and to incorporate, the Conservators of Ashdown Forest; to alter the arrangements for meeting the expenses of the Conservators; to amend or repeal enactments relating to the Conservators and the forest and to confer further powers upon the Conservators; and for other purposes. |

| Citation | 1974 c. xxi |

| Dates | |

| Royal assent | 31 July 1974 |

| Other legislation | |

| Repeals/revokes |

|

Status: Current legislation | |

| Text of statute as originally enacted | |

Following the conclusion of the Ashdown Forest case, a board of conservators was established by act of Parliament in 1885 to oversee the forest bye-laws, including the protection of commoner's rights. More acts of Parliament followed, which further refined the governance of the forest, culminating in the Ashdown Forest Act 1974.

Sale of the forest into public ownership

[edit]In the 1980s the Lord of the Manor, William Sackville, 10th Earl De La Warr, offered Ashdown Forest for sale direct to the local authority, East Sussex County Council, if they would buy it; otherwise he would probably sell the forest piecemeal on the open market.[74] On 25 November 1988 this threat to split up the forest was averted when, with the benefit of donations from many sources, including the proceeds of a public appeal, East Sussex County Council purchased the freehold of Ashdown Forest from the executors of the Earl, who had died the previous February. The freehold was then vested by the council in a newly created charitable trust, the Ashdown Forest Trust.

The iron industry of Ashdown Forest

[edit]Ashdown Forest's iron industry flourished in the two eras when the Weald was the main iron-producing region of Britain, namely in the first 200 years of the Roman period (1st to 3rd centuries AD) and in the Tudor period (late 15th and 16th centuries). Ashdown was favoured by the widespread presence of iron-ore, extensive woodlands for the production of charcoal, and deep, steep-sided valleys (locally known as ghylls) that could be dammed to provide water power for furnaces and forges.

The forest is the site of Britain's first confirmed blast furnace, at Newbridge, which began operation in 1496.[75] Henry VII commissioned it for the production of heavy metalwork for gun carriages for his war against the Scots. Immigrants from Northern France brought with them the technology for a furnace that they would operate.[76]

Spurred by the development of blast furnaces, the iron industry grew very rapidly during the 16th century and would become noted for the casting of cannons and cannonballs for the English navy. The celebrated ironmaster and gunfounder Ralph Hogge, who in 1543 made the first one-piece, cast-iron cannon in England at nearby Buxted, drew his raw materials from the southern part of the forest. However, the huge demand for raw materials and fuel, particularly charcoal, heavily depleted Ashdown Forest's woodlands, causing much concern and prompting commissions of enquiry by the king. In due course coppice management was used to ensure a more sustainable supply.

In the 17th century the industry would die out as a result of competition from lower-cost iron-producing areas.

Archaeology

[edit]

Ashdown Forest is rich in archaeology: there are more than 570 archaeological sites, including Bronze Age round barrows, Iron Age enclosures, prehistoric field systems, Roman iron workings, the medieval pale, medieval and post-medieval pillow mounds for the rearing of rabbits, and remains of late 18th-century military kitchen mounds that are among the only surviving ones in the United Kingdom.[77]

The earliest known trace of human activity in Ashdown Forest is a stone hand axe found near Gills Lap, which is thought to be about 50,000 years old.[78] The vast majority of finds date from the Mesolithic (10,000-4,000 BC) and onwards into the modern era.

The London to Lewes Way, one of three Roman roads that connected London with the important Wealden iron industry, crosses Ashdown Forest in a north–south direction, and would have been used to transport iron products from the forest to London and the coast. The agger of the road, whose foundations include iron slag, can be seen at Roman Road car park.

Ownership and administration

[edit]The freehold of Ashdown Forest, which essentially consists of the common land set aside in 1693, when the ancient forest was divided up by decree of the Duchy of Lancaster, plus a number of later land acquisitions, is owned by the Ashdown Forest Trust, a registered charity controlled and managed by East Sussex County Council. Ownership was vested in the trust after the council bought the freehold from the executors of the Lord of the Manor, the 10th Earl De La Warr, in November 1988. This purchase was the culmination of a high-profile and passionate fund-raising campaign by members of the public, which included a £175,000 endorsement by Christopher Robin Milne (by then living and working in Devon), who were concerned that the earl's stated intention, in the absence of a purchase of the forest by the county council, was to sell it piecemeal into private hands, a possibility which seemed to become more likely when the earl died before the contract could be completed. Fortunately, the county council was able to complete the purchase from the executors, the council matching the amount raised by the public campaign to enable the asking price of over £1 million to be met.[79]

The forest is regulated and protected by an independent Board of Conservators established under the Ashdown Forest Act 1885. The creation of the board followed the resolution of the protracted 19th-century dispute between the commoners and the 7th Earl De La Warr over rights of common on the forest. The structure of the board, originally composed entirely of commoners, altered significantly during the 20th century. Currently, of its sixteen members, nine are appointed by East Sussex County Council (one of whom represents the lord of the manor, the Ashdown Forest Trust), two by Wealden District Council, and the remaining five are elected by the commoners, of whom four must be commoners. The day-to-day management of the forest is the responsibility of a director, Mrs Pat Buesnel, the clerk to the conservators, Mrs Ros Marriott, and a number of supporting staff, including a team of forest rangers.

The conservators are required to act in accordance with a number of acts of Parliament pertaining to the forest, of which the latest, the Ashdown Forest Act 1974, states (section 16):

It shall be the duty of the Conservators at all times as far possible to regulate and manage the forest as an amenity and place of resort subject to the existing rights of common upon the forest and to protect such rights of common, to protect the forest from encroachments, and to conserve it as a quiet and natural area of outstanding beauty.

A number of byelaws have been passed by the conservators under the 1974 act to protect the forest and to preserve its perceived special character, particularly its tranquillity. These include prohibitions on off-roading driving, mountain-biking, horse-riding (except by permit), camping, the lighting of fires, digging and the dumping of rubbish.[80]

Finding adequate funding for the regulation and conservation of the forest has been a persistent issue. The income of the conservators in 2009-10 was £751,000, of which almost half was accounted for by funding from the government's Higher Level Stewardship (HLS) scheme, which requires the conservators to achieve certain objectives, such as restoring the heathlands to "favourable condition". Grants from the local authorities and the Ashdown Forest Trust accounted for another fifth. In 2009-10 there was a small surplus of income over expenditure (57% of which was staff costs). Cuts in local government expenditure and the ending of the current programme of HLS funding in 2016 present major challenges.[81]

Large numbers of volunteers support the work of the conservators by undertaking conservation work in the forest. Many of these are recruited by the Friends of the Ashdown Forest,[82] which has almost 1000 members. Fundraising by the Friends has helped towards the purchase of capital equipment for forest management such as motor vehicles and enabled the conservators to buy back parcels of land within the ancient pale for re-incorporation into the forest.

In 1994 the Board of Conservators, with the help of funding from East Sussex County Council, purchased 28 hectares (69 acres) of woodland at Chelwood Vachery (an estate that dates back to at least 1229), including an early 20th-century garden and lake system, after the estate was divided up and offered for sale by its owner. The land is now undergoing restoration as a forest garden and is open to the public.

Ashdown Forest's common land and its commoners

[edit]

The common land of Ashdown Forest, amounting to some 6,400 acres (2,600 ha), consists of specific areas of the forest, registered under the Commons Registration Act 1965, which only those who possess particular rights of common - commoners - are entitled to use and exploit in certain specified ways. These common rights are attached to certain landholdings around the forest, not to individual people, and are passed on when properties are sold or inherited. Since 1885 the common land has been regulated and protected by a statutory Board of Conservators.

Contrary to widespread belief, a 'common' in England is not 'public land'. However, in the case of Ashdown Forest, the conservators have given the public open access to the common land, subject to compliance with bye-laws that largely aim to preserve the special character of the forest.

A right of common may be defined as:

...a right, which one or more persons may have, to take or use some portion of that which another man's soil naturally produces...[83]

On Ashdown Forest the rights of common have varied over time. Those that remain today, which are subject to local byelaws and are under the control of the conservators, are:[84]

- pasturage (or grazing rights): the right to graze sheep, cattle, goats, geese or mill horses (horses that provide power for the mill) on the forest.[85]

- estovers: today, understood to be the right to cut birch, willow or alder for use in the "ancestral hearth", which may only be exercised at certain times and in certain areas designated by the conservators.

- brakes and litter: the right to cut brake (bracken) and heather and to collect litter for the principal purpose of bedding down livestock in winter on the land-holding.

Today, to a varying degree, every property possessing common rights has some or all of these rights over the registered common land of the forest.

To become a commoner a person must acquire commonable land; conversely, a person selling a commonable property ceases to be a commoner. Where a commonable property is sold off in smaller portions, the commonable rights are apportioned in accordance with the area of each portion.[86] All commoners are obliged to pay a Forest Rate (based on the area of commonable land held) to contribute towards the administration of the forest by the Board of Conservators, and they are entitled to elect five commoners' representatives to the Board.

A sharp decline in commoning after the end of World War II resulted in a rapid loss of the forest's open heathland to scrub and trees, threatening the many specialised and rare plants and animals that depend on the heathland and jeopardising the forest's famous open landscape with its magnificent vistas, so well captured in EH Shepard's Winnie-the-Pooh illustrations. The Board of Conservators has responded by moving beyond its original administrative and regulatory functions to play a more active, interventionist role in combating the invasion of scrub and trees with the aim of restoring the heathland to a favourable condition.

Notable people

[edit]- A. A. Milne, author of the Winnie-the-Pooh stories, lived at Cotchford Farm, near Hartfield, having bought the old farmhouse, situated about a mile from the ancient forest entrance at Chuck Hatch, in 1925.

- Brian Jones of the Rolling Stones also lived at Cotchford Farm, and died there in 1969.

- Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, author of the Sherlock Holmes stories, lived at Crowborough, on the eastern edge of the forest. Locations around the forest found their way into his stories.

- Richard Jefferies, nature writer, lived at Crowborough for a period while he wrote some of his most famous essays.[87]

- Harold Macmillan, former British Prime Minister, lived at Birch Grove, near Chelwood Gate; the Macmillan Clump of trees is named in his honour.

- Major Edward Dudley Metcalfe, best friend and equerry of Edward VIII,[88] lived in a grey stone house in the forest.

- The Irish poet W. B. Yeats, and his wife Georgie Yeats spent their honeymoon at the forest, during October – November 1917, at the Ashdown Forest Hotel, Forest Row, East Sussex, which was renamed and is now called Royal Ashdown Forest Golf Club.[89] During the course of their honeymoon, the couple experimented with automatic writing, a joint experience that greatly influenced the poetry of Yeats and led to the publication of his philosophical–esoterical book A Vision.

References

[edit]- ^ a b c "Welcome to Ashdown Forest". Ashdownforest.org. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ a b c Hope, Yvonne Jefferey (2000). "Winnie-the-Pooh in Ashdown Forest". In Brooks, Victoria (ed.). Literary Trips: Following in the Footsteps of Fame. Vol. 1. Vancouver, Canada: Greatest Escapes. p. 287. ISBN 0-9686137-0-5.

- ^ a b Willard, Barbara (1989). The Forest – Ashdown in East Sussex. Sussex: Sweethaws Press.. Quoted from the Introduction, p. xi, by Christopher Milne.

- ^ a b c "Ashdown Forest background (where it all happened): Shepard, E. H." V&A. Retrieved 26 April 2023.

- ^ "An Introduction To Britain's Lost Wildwood". South-coast-central.co.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ A. Mawer & F.M. Stenton, The Place Names of Sussex (1929), 1,1, 2.

- ^ 'Forest' is derived from the term 'forestis', which first appeared in the early Middle Ages in deeds of donation of the Merovingian and Frankish kings and is thought to refer to wilderness that had not been cultivated and which had no clear owner; such wilderness lay beyond land that was cultivated and settled and which did have a clear owner. The majority view of scholars about the origin of the concept of "forestis" is that it is derived from the Latin foris or foras, which means "outside", "outside it" and "outside the settlement". Forest law introduced by the Normans came to govern for a time almost one-third of England, before being rolled back in the 13th century. Unlike the case on the European continent, it also applied to areas that did have a clear owner. See Vera (2000), pp.103-108 and Langton and Jones (2008).

- ^ Straker (1940), p. 121.

- ^ Christian (1967), p. 28.

- ^ There are only three older outcrops, which are Jurassic Purbeck Beds, a thin limestone, are at Heathfield, Brightling and Mountfield, all in east Sussex.

- ^ Tunbridge Wells Sand consists of Upper Tunbridge Wells Sand, Grinstead Clay, and Lower Tunbridge Wells Sand.

- ^ Leslie & Short (1999), p. 2.

- ^ The iron ore is a clay ironstone, a low grade iron ore largely consisting of siderite. It is distributed widely across the Wealden geology. See Gallois (1965), pp. 24-26

- ^ Leslie and Short (1999), pp. 4-5.

- ^ The remaining 5% (112 ha) consists of car parks, picnic areas, golf courses, etc.

- ^ Note: the figures quoted here refer to the land administered by the conservators, and exclude all privately held land.

- ^ Strategic Forest Plan of the Board of Conservators of Ashdown Forest 2008-2016, p. 2.

- ^ Strategic Forest Plan of the Board of Conservators of Ashdown Forest 2008-2016, p. 9.

- ^ "Birds of Ashdown Forest". Archived from the original on 12 February 2010.

- ^ Annual Report of the Board of Conservators of Ashdown Forest 2009/2010, p.4. Archived 14 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Grazing". The Conservators of Ashdown Forest. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ "Heathland and moorland | The Wildlife Trusts". www.wildlifetrusts.org. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ William Cobbett, Sussex Journal entry of 8 January 1822, in Rural Rides. Constable, London. 1982. ISBN 0-09-464060-2.

- ^ Indeed, according to Oliver Rackham, the beginnings of Wealden heathland, including Ashdown's, which he calls a heathland forest, can be traced back to before the Norman Conquest. See Rackham (1997), p. 134.

- ^ a b Strategic Forest Plan of the Board of Conservators of Ashdown Forest 2008-2016.

- ^ Victoria County History of Sussex, Volume II, p. 314.

- ^ Straker (1940), p. 123.

- ^ Annual Report of the Board of Conservators of Ashdown Forest 2007/2008, p. 2.

- ^ Penn (1984), p. 195.

- ^ "Designated Sites View: Ashdown Forest". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ "Map of Ashdown Forest". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 11 January 2019.

- ^ "Ashdown Forest". Jncc.gov.uk. Archived from the original on 28 February 2006. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Designated Sites View: Ashdown Forest". Special Areas of Conservation. Natural England. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ Ratcliffe, Derek, ed. (1977). A Nature Conservation Review. Vol. 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. p. 115. ISBN 0521-21403-3.

- ^ "Designated Sites View: Old Lodge, Nutley". Local Nature Reserves. Natural England. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ "Old Lodge". Sussex Wildlife Trust. Retrieved 10 January 2019.

- ^ "Sussex Biodiversity Action Plan". 11 July 2002. Archived from the original on 11 July 2002. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Parking". Ashdown Forest. Archived from the original on 14 June 2021.

- ^ "Parking charges on Ashdown Forest". 26 October 2021.

- ^ "Getting around by train – East Sussex County Council". Eastsussex.gov.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ a b "How to Get Here - Ashdown Forest". Ashdownforest.com. 25 March 2014. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Bus travel in East Sussex – East Sussex County Council". Eastsussex.gov.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Welcome to Ashdown Forest". Ashdownforest.com. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Ashdown Forest, home of the Conservators and Pooh Bear". Archived from the original on 23 February 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2010. Source of Ashdown Forest walks leaflets

- ^ "Ashdown Forest Riding Association". Afranews.org.uk. Archived from the original on 21 September 2017. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "The Hell of Ashdown - Welcome". 11 January 2010. Archived from the original on 11 January 2010. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Ashdown Cycling Campaign". Archived from the original on 4 August 2009. Retrieved 16 March 2010. Ashdown Cycling Campaign website

- ^ "Home". Royalashdown.co.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Hotels in Sussex - Ashdown Park Luxury Spa Hotel East Grinstead, Sussex". Ashdownpark.com. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ http://www.ashdownforest.org/about/forest_centre.phphere [permanent dead link]

- ^ "Sussex Wildlife Trust - Old Lodge". 20 September 2007. Archived from the original on 20 September 2007. Retrieved 30 March 2019.

- ^ "Old Lodge, Nutley". Local Nature Reserves. Natural England. Archived from the original on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ "Map of Old Lodge, Nutley". Local Nature Reserves. Natural England. Retrieved 4 August 2013.

- ^ Singleton, Tony. "Wealden Iron Research Group Home Page". Wealdeniron.org.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "The Hatch Inn". Users.globalnet.co.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ "Ashdown Forest Tourism Association - Local Information, Places to Visit and News & Events from the Heart of the High Weald". Archived from the original on 28 May 2009. Retrieved 18 January 2010.

- ^ "Tracing the Pale of Ashdown Forest". High Weald website.

- ^ Milne (1974), p. 62.

- ^ Milne (1974), p. 61.

- ^ "Pooh Corner". Pooh-country.co.uk. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ The Conservator's of Ashdown Forest Newsletter 1987.

- ^ Brandon (2003), Chapters 2 and 6. Note that the Saxon prefix Andredes was probably derived from Anderida, the name of the Romans' stronghold at Pevensey.

- ^ Small (1988), p. 156.

- ^ Victoria County History of Sussex, Volume II, p. 315.

- ^ "Plea Rolls of the Court of Common Pleas; National Archives; CP 40/541, year: 1396". Aalt.law.uh.edu. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

entries 4 & 5, asserting his hunting rights

- ^ Straker (1940), p. 124.

- ^ Christian (1967), p. 2.

- ^ "History | Pippingford Park". Archived from the original on 13 November 2012. Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ^ "Broadstone Warren Scout Site & Activity Centre". Retrieved 23 September 2012.

- ^ "London Youth - Supporting and challenging young people to become the best they can be". Londonyouth.org.uk. Archived from the original on 28 January 2016. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ a b Hinde (1987), p. 66.

- ^ Short (1997).

- ^ "The Weald - Books, directories, magazines and pamphlets". Theweald.org. Archived from the original on 4 January 2009. Retrieved 16 December 2017.

- ^ Willard (1989), p.167.