Poster

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2013) |

A poster is a large sheet that is placed either on a public space to promote something or on a wall as decoration.[1][2][3] Typically, posters include both textual and graphic elements, although a poster may be either wholly graphical or wholly text. Posters are designed to be both eye-catching and informative. Posters may be used for many purposes. They are a frequent tool of advertisers (particularly of events, musicians, and films), propagandists, protestors, and other groups trying to communicate a message. Posters are also used for reproductions of artwork, particularly famous works, and are generally low-cost compared to the original artwork. The modern poster, as we know it, however, dates back to the 1840s and 1850s when the printing industry perfected colour lithography and made mass production possible.[4]

History

[edit]

Toulouse-Lautrec, 1891

Introduction

[edit]According to the French historian Max Gallo, "for over two hundred years, posters have been displayed in public places all over the world. Visually striking, they have been designed to attract the attention of passers-by, making us aware of a political viewpoint, enticing us to attend specific events, or encouraging us to purchase a particular product or service."[5] The modern poster, as we know it, however, dates back to the mid-nineteenth century, when several separate, but related, changes took place. First, the printing industry perfected colour lithography and made mass production of large and inexpensive images possible. Second, government censorship of public spaces in countries such as France was lifted. And finally, advertisers began to market mass-produced consumer goods to a growing populace in urban areas.[6]

"In little more than a hundred years", writes poster expert John Barnicoat, "it has come to be recognized as a vital art form, attracting artists at every level, from painters such as Toulouse-Lautrec and Mucha to theatrical and commercial designers."[7] They have ranged in styles from Art Nouveau, Symbolism, Cubism, and Art Deco to the more formal Bauhaus and the often incoherent hippie posters of the 1960s.

Mass production

[edit]

Posters, in the form of placards and posted bills, have been used since earliest times, primarily for advertising and announcements. Purely textual posters have a long history: they advertised the plays of Shakespeare and made citizens aware of government proclamations for centuries. The great revolution in posters, however, was the development of printing techniques that allowed for cheap mass production and printing, notably including the technique of lithography, which was invented in 1796 by the German Alois Senefelder. The invention of lithography was soon followed by chromolithography, which allowed for mass editions of posters illustrated in vibrant colors to be printed.

Developing art form

[edit]By the 1890s, the technique had spread throughout Europe. A number of noted French artists created poster art in this period, foremost amongst them Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Jules Chéret, Eugène Grasset, Adolphe Willette, Pierre Bonnard, Louis Anquetin, the brothers Léon and Alfred Choubrac, Georges de Feure, and Henri-Gabriel Ibels.[8] Chéret is considered to be the "father" of advertisement placards. He was a pencil artist and a scene decorator, who founded a small lithography office in Paris in 1866. He used striking characters, contrast, and bright colors, and created more than 1000 advertisements, primarily for exhibitions, theatres, and products. The industry soon attracted the service of many aspiring painters who needed a source of revenue to support themselves.

Chéret developed a new lithographic technique that better suited the needs of advertisers: he added a lot more colour which, in conjunction with innovative typography, rendered the poster much more expressive. Chéret is said to have introduced sexuality in advertising or, at least, to have exploited the feminine image as an advertising ploy. In contrast with those previously painted by Toulouse-Lautrec, Chéret's laughing and provocative feminine figures, often called "chérettes", meant a new conception of art as being of service to advertising.

Posters soon transformed the thoroughfares of Paris, making the streets into what one contemporary called "the poor man's picture gallery."[9] Their commercial success was such that some fine artists took up poster design in earnest. Some of these artists, such as Alphonse Mucha, were in great demand and theatre stars personally selected their own favorite artist to do the poster for an upcoming performance. The popularity of poster art was such that in 1884 a major exhibition was held in Paris.

Golden age

[edit]

By the 1890s, poster art had widespread use in other parts of Europe, advertising everything from bicycles to bullfights. By the end of the nineteenth century, during an era known as the Belle Époque, the standing of the poster as a serious art form was raised even further. Between 1895 and 1900, Jules Chéret created the Maîtres de l'Affiche series (Masters of the Poster) that became not only a commercial success, but is now recognized as an important historical publication.

Eugène Grasset and Alphonse Mucha were also influential poster designers of this generation, known for their Art Nouveau style and stylized figures, particularly of women. Advertisement posters became a special type of graphic art in the modern age. Poster artists such as Théophile Steinlen, Albert Guillaume, Leonetto Cappiello, Henri Thiriet, and others became important figures of their day, their art form transferred to magazines for advertising as well as for social and political commentary. Indeed, as design historian Elizabeth Guffey notes, "As large, colorful posters began to command the spaces of public streets, markets, and squares, the format itself took on a civic respectability never afforded to Victorian handbills."[10]

In the United States, posters underwent a slightly different evolution. By the 1850s, the advent of the traveling circus brought colorful posters to tell citizens that a carnival was coming to town. While many of these posters were beautifully printed, the earliest were mass-produced woodcuts; that technique, as well as their subject matter, crowded style, and bright colors, was often derided by contemporary critics. As chromo-lithography began to reshape European posters, American artists began to take that medium more seriously. Indeed, the work of designers such as Edward Penfield and Will Bradley gained an audience in Europe as well as America.

Decline and resurgence

[edit]Challenged by newer modes of advertising, the poster as a communicative tool began to decline after the First World War. Civic groups had long assailed the poster, arguing that the nature of the poster made public spaces ugly. But the real threat to posters came from newer forms of advertising. Mass-market magazines, radio, and later, television, as well as billboards all cut into advertiser's marketing budgets. While posters continued to be made and advertised products, they were no longer considered a primary form of advertising. More and more, the purpose of posters shifted toward political and decorative uses.

Indeed, by the mid 1960s, posters were reborn as part of a broader counter-cultural shift. By 1968 the contemporary poster resurgence was described as "half way between a passing fashion and a form of mass hysteria."[11] Sometimes called a "second golden age" or "postermania"[12] however, this resurgence of popularity saw posters used as decoration and self-expression as much as public protest or advertising.[13]

Commercial uses

[edit]

By the 1890s, poster art had widespread use in other parts of Europe, advertising everything from bicycles to bullfights. Many posters have had great artistic merit. These include the posters advertising consumer products and entertainment, but also events such as the World's Fairs and Colonial Exhibitions.

Political uses

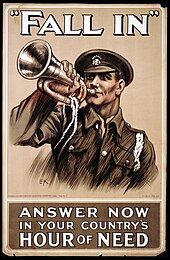

[edit]The first widespread use of illustrated posters for political ends occurred during the First World War. War bond drives and recruitment posters soon replaced commercial advertisements. German graphic designers who had pioneered the simple Sachplakat style in the years leading up to the war, applied their talents to the war effort. Artists working for the Allied cause also adapted their art in wartime, as well.

During the Second World War many posters were distributed by the U.S. government and often were displayed in post offices. Many were designed to provide rationale for adaptation to the rationing of supplies such as gasoline and foods.

The 1960s saw the rise of pop art and protest movements throughout the West; both made great use of posters and contributed to the revitalization of posters at this time. Perhaps the most acclaimed posters were those produced by French students during the so-called, "événements", of May 1968. During the 1968 Paris student riots and for years to come, Jim Fitzpatrick's stylized poster of Marxist revolutionary Che Guevara (based on the photograph, Guerrillero Heroico), also became a common youthful symbol of rebellion.[14]

After the September 11 attacks, in the United States, public schools across the country hung framed posters of "In God We Trust" in their "libraries, cafeterias, and classrooms." The American Family Association supplied several 11-by-14-inch posters to school systems.[15]

Printing

[edit]Many printing techniques are used to produce posters. While most posters are mass-produced, posters may also be printed by hand or in limited editions. Most posters are printed on one side and left blank on the back, the better for affixing to a wall or other surface. Pin-up sized posters are usually printed on A3 Standard Silk paper in full colour. Upon purchase, most commercially available posters are often rolled up into a cylindrical tube to allow for damage-free transportation. Rolled-up posters may then be flattened under pressure for several hours to regain their original form.

It is possible to use poster creation software to print large posters on standard home or office printers.

Collecting

[edit]There exists a community that collect rare or vintage posters, analogous to fine art collectors. Popular categories include Belle Époque, movies, war and propaganda, and travel. Because of their low cost, the number of forged posters is relatively low compared to other mediums.[16] The International Vintage Poster Dealers Association (IVPDA) maintains a list of reputable poster dealers.[17] Collectable poster artists include Jules Chéret, Henri de Toulouse-Lautrec, Alphonse Mucha, and Théophile Steinlen.

Types

[edit]Many posters, particularly early posters, were used for advertising products. Posters continue to be used for this purpose, with posters advertising films, music (both concerts and recorded albums), comic books, and travel destinations being particularly notable examples.

Propaganda and political

[edit]

During the First and Second World Wars, recruiting posters became extremely common, and many of them have persisted in the national consciousness, such as the "Lord Kitchener Wants You" posters from the United Kingdom, the "Uncle Sam wants you" posters from the United States, or the "Loose Lips Sink Ships" posters[18] that warned of foreign spies. Also in Canada, they were widespread.[19]

Posters during wartime were also used for propaganda purposes, persuasion, and motivation, such as the famous Rosie the Riveter posters that encouraged women to work in factories during World War II. The Soviet Union also produced a plethora of propaganda posters,[20] some of which became iconic representations of the Great Patriotic War.

During the democratic revolutions of 1989 in Central and Eastern Europe the poster was a very important weapon in the hand of the opposition. Brave printed and hand-made political posters appeared on the Berlin Wall, on the statue of St. Wenseslas in Prague, and around the unmarked grave of Imre Nagy in Budapest. Their role was indispensable for democratic change. An example of an influential political poster is Shepard Fairey's, Barack Obama "HOPE" poster.

Movie

[edit]The film industry quickly discovered that vibrantly coloured posters were an easy way to sell their films. Today, posters are produced for most major films, and movie posters are some of the most actively collected. The record price for a poster was set on November 15, 2005 when US$690,000 was paid for a poster of Fritz Lang's 1927 film, Metropolis, from the Reel Poster Gallery in London.[21] Other early horror and science fiction posters are known to bring tremendous prices as well, with an example from The Mummy realizing $452,000 in a 1997 Sotheby's auction,[21] and posters from both The Black Cat and Bride of Frankenstein selling for $334,600 in various Heritage Auctions.[22] The 1931 Frankenstein 6-sheet poster, of which only one copy is known to exist, is considered to be the most valuable film poster in the world.[23]

Travel

[edit]Poster advertising, proposing a travel destination, or simply artistically articulating a place have been made. An example is the Beach Town Posters series, a collection of Art Deco travel posters of American beach resorts that epitomise the advertising style of the 1920s and 1930s.[citation needed]

Railway

[edit]In the early days of steam powered railways in Britain, the various rail companies advertised their routes and services on simple printed sheets. By the 1850s, with increasing competition and improvements in printing technology, pictorial designs were being incorporated in their advertising posters. The use of graphic artists began to influence the design of the pictorial poster. In 1905, the London and North Western Railway (LNWR) commissioned Norman Wilkinson to produce artwork for a new landscape poster, advertising their rail and steam packet link to Ireland. In 1908, for the Great Northern Railway (GNR), John Hassall produced the famous image of the "Jolly Fisherman" with the "Skegness is so Bracing" slogan. Fortunino Matania painted a number of posters for the LMS. The development of this commercial art form throughout the first half of the twentieth century reflected the changes in British society, along with the changing styles of art, architecture, and fashion as well as changing patterns of holiday making.[24] Terence Cuneo produced poster art for the London, Midland and Scottish Railway, the London and North Eastern Railway, and British Railways.[25] Sheffield artist, Kenneth Steel, produced posters for British Railways.[26]

Event

[edit]

Posters advertising events have become so common that any sort of public event, from a rally to a play, may be advertised with posters. A few types of events have become notable for their poster advertisements.

Boxing

[edit]Boxing Posters were used in and around the venue to advertise the forthcoming fight, date, and ticket prices, and they usually consisted of pictures of each boxer. Boxing Posters vary in size and vibrancy, but are not usually smaller than 18x22 inches. In the early days, few boxing posters survived the event and have thus become a collectible.

Concert

[edit]Many concerts, particularly rock concerts, have custom-designed posters that are used as advertisement for the event. These often become collectors items as well.

Music group promotional

[edit]Posters that showcase a person's favorite artist or music group are popular in teenagers' bedrooms, as well as in college dorm rooms and apartments. Many posters have pictures of popular rock bands and artists.

Blacklight

[edit]Blacklight posters are designed to fluoresce or glow under a black light (ultraviolet light).

Pin-up

[edit]Pinup posters, "pinups", or "cheesecake" posters are images of attractive women designed to be displayed. They first became popular in the 1920s. The popularity of pin-up girl posters has been erratic in recent decades. Pin-ups such as Betty Grable and Jane Russell were highly popular with soldiers during World War II, but much less so during the Vietnam War. Large posters of television actresses, for example the red swimsuit poster of Farrah Fawcett and the pink bikini poster of Cheryl Tiegs, became popular during the 1970s and into the early 1980s.

Affirmation

[edit]

This refers to decorative posters that are meant to be motivational and inspirational. One popular series has a black background, a scene from nature, and a word such as "Leadership" or "Opportunity". Another version (usually framed and matted) uses a two-image hologram that changes as the viewer walks past.

Comic book

[edit]The resurgence of comic book popularity in the 1960s led to the mass production of comic book posters in the 1970s and onward. These posters typically feature popular characters in a variety of action poses.

The fact that comic books are a niche market means that a given poster usually has a smaller printing run than other genres of poster. Therefore, older posters may be quite sought after by collectors.

Promotional posters are usually distributed folded, whereas retail posters intended for home decoration are rolled.

Educational

[edit]Research and "poster sessions"

[edit]Posters are used in academia to promote and explain research work.[27] They are typically shown during conferences, either as a complement to a talk or scientific paper, or as a publication. They are of lesser importance than articles, but they can be a good introduction to a new piece of research before the paper is published. They may be considered as grey literature. Poster presentations are often not peer-reviewed, but may instead be submitted, meaning that as many as can fit will be accepted.

Poster sessions have also been used as an alternative to oral presentations as a form of assessment.[28][29][30]

Classroom

[edit]Posters are a standard feature of classrooms worldwide. A typical school in North America will display a variety, including: advertising tie-ins (e.g. an historical movie relevant to a current topic of study): alphabet and grammar, numeracy and scientific tables, safety and other instructions (such as lab safety and proper hand washing), artwork, and those created by the students for display.

See also

[edit]- The Tennis Girl poster was an iconic image from the late 1970s

- Graphic design

- Grey literature

- Illustrations

- List of poster artists

- Mediascape

- Pin-up (disambiguation)

- Street Poster Art

- Swann Galleries

References

[edit]- ^ "poster noun". Oxford Dictionaries. Archived from the original on 27 April 2018. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ "poster noun". Merriam Webster. Archived from the original on 6 August 2022. Retrieved 6 August 2022.

- ^ Lippert, Angelina (18 August 2017). "What is a poster?". article. Poster House. Archived from the original on 18 July 2019. Retrieved 18 July 2019.

- ^ Stephen Eskilson, Graphic Design: A New History, Yale University Press, 2012, pp. 43–47.

- ^ Gallo, Max, The Poster in History, (2002) W.W. Norton

- ^ Elizabeth Guffey, Posters: A Global History, Reaktion: 2015, pp. 8-9.

- ^ Barnicoat, John, Posters: A Concise History, (1985) Thames and Hudson

- ^ The modern poster by Arsène Alexandre

- ^ Roger Marx, Masters of the Poster, 1896–1900 (New York, 1977), p. 7.

- ^ Guffey, op cit, p. 13.

- ^ David Kunzle, Posters of Protest: The Posters of Political Satire in the U.S., 1966–1970 (New York, 1971), p. 14.

- ^ Hilton Kramer, 'Postermania', New York Times Magazine (11 February 1968).

- ^ Guffey, op cit, 127.

- ^ Che Guevara: Revolutionary & Icon, by Trisha Ziff, Abrams Image, 2006, pg 19

- ^ "'In God We Trust' pressed for schools - USA Today". Usatoday30.usatoday.com. 2002-02-19. Archived from the original on 2013-11-11. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ Hunter, Lisa (2006). The Intrepid Art Collector. New York: Three Rivers Press. p. 123. ISBN 0307237133.

- ^ "Our Members - International Vintage Poster Dealers Association - Authentic Posters, Expert Dealers". www.ivpda.com. Archived from the original on 2021-07-18. Retrieved 2021-07-18.

- ^ [1] Archived October 22, 2006, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Canadian War Poster Collection". Digital.library.mcgill.ca. Archived from the original on 2013-02-07. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ "Propaganda posters - Collection of 1400+ POSTERS from Russia, Czech republic, Poland and Cuba". Posters.nce.buttobi.net. Archived from the original on 2018-07-11. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ a b "Lang film poster fetches record". BBC News. 2005-11-15. Archived from the original on 2020-07-31. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- ^ "Heritage Auctions Search [54 790 231]". Archived from the original on 2011-10-05. Retrieved 2010-12-13.

- ^ BIRD GEI Consultoria Idiomas. "http://birdgei.com/2012/02/07/film-posters/ Archived 2015-10-16 at the Wayback Machine"

- ^ "Railway posters - Our collection - National Railway Museum". Nrm.org.uk. 2009-10-13. Archived from the original on 2016-01-28. Retrieved 2013-02-28.

- ^ "Terence Cuneo: the railway artist with a surprising lucky charm | Art UK". www.artuk.org. Archived from the original on 2019-01-17. Retrieved 2019-01-17.

- ^ "Sheffield's Kenneth Steel: The famous rail travel artist you have never heard of". BBC News. 27 December 2021. Archived from the original on 27 December 2021. Retrieved 27 December 2021.

- ^ Ivaska, L; Torres-Simón, E (2020). "State of the art and seven tips for improvement". Electronic Journal of the KäTu Symposium on Translation and Interpreting Studies. 13: 138–157.

- ^ Hughes, A (2005). "A Poster Project for an Undergraduate Sensation and Perception Course". Teaching of Psychology. 32 (1): 58–59.

- ^ Using Poster Presentation Activities for Assessment in Higher Education. ICERI2023 Proceedings. IATED. 2023. pp. 1758–1764. doi:10.21125/iceri.2023.0518.

- ^ Miller, C T (2023). "Classroom Trade Show: An Alternative to Traditional Classroom Presentations in an Undergraduate Plant Identification Course". HortTechnology. 33: 111–117. doi:10.21273/HORTTECH05148-22.

Further reading

[edit]- Josef Müller-Brockmann: Geschichte des Plakates Phaidon Press 2004, ISBN 978-0714844039

- Franz-Josef Deiters: Bilder ohne Rahmen: Zur Rhetorik des Plakats, in: Medienrhetorik, ed. by Joachim Knape. Attempto, Tübingen (Germany) 2005, ISBN 3-89308-370-7, S. 81–112.

- Franz-Josef Deiters: Plakat, in: Historisches Wörterbuch der Rhetorik, ed by. Gert Ueding (et al.). Max Niemeyer, Tübingen (Germany) 2003, ISBN 3-484-68100-4, vol. 6, pp. 1230–39.

- New Masters of Poster Design. John Foster, Rockport Publishers 2008 ISBN 978-1592534340

- 100 Best Posters - NO ART. Hermann Schmidt Publisher 2006, Fons Hickmann, Niklaus Troxler ISBN 978-3874397032

- Fons Hickmann, Sven Lindhorst-Emme (Hrsg) Anschlag Berlin - Zeitgeistmedium Plakat. Verlag Seltmann+Söhne, Berlin 2015, ISBN 978-3-944721-56-9

- Gosling, Peter. (1999). Scientist's Guide to Poster Presentations. New York: Kluwer. ISBN 978-0-306-46076-0.

- King, Emily. (2003). A Century of Movie Posters: From Silent to Art House. Barron's. ISBN 978-0-7641-5599-4.

- Noble, Ian. (2002). Up Against the Wall: International Poster Design. Mies, Switzerland: RotoVision. ISBN 978-2-88046-561-2.

- Timmers, Margaret. (2003). Power of the Poster. Victoria and Albert Museum. ISBN 978-0-8109-6615-4.

- Le Coultre, Martijn F. & Purvis, Alston W. (2002) A Century of Posters, Lund Humphries ISBN 978-0-85331-863-7

- Rennert, Jack. (1990). Posters of the Belle Epoque, Wine Spectator Press, ISBN 978-0-9664202-1-0

- Wrede, Stuart. (1988). The Modern Poster, Little Brown and Company, ISBN 978-0-87070-570-0

- Gold, Laura. (1988). Posters, Please ISBN 978-0-9664202-0-3

- Cole, Beverley & Durack, Richard (1992), Railway Posters 1923–1947, Laurence King, ISBN 978-1-85669-014-0

- Kempa, Karolina. (2018). Polnische Kulturplakate im Sozialismus. Eine kunstsoziologische Untersuchung zur (Be-)Deutung des Werkes von Jan Lenica und Franciszek Starowieyski, Wiesbaden: Springer, ISBN 978-3658188542

- Salter, Colin. (2020). 100 Posters that Changed the World. London: Pavilion Books ISBN 978-1-911641-45-2

- Hillier, Bevis. (1972). 100 Years of Posters. London: Pall Mall Press ISBN 0269028382

External links

[edit]- . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 22 (11th ed.). 1911.

- Posters from World War I and II – A selection of posters covering subjects such as recruitment and enlisting, saving stamps and munitions, from the UBC Library Digital Collections

- World War I and World II Poster Collection - featuring propaganda posters and broadsides from the United States, Western Europe and the Axis powers from the University of Washington Library

- circusmuseum.nl Features nearly 8,000 circus posters from 1880 to the present

- London Transport posters Over 5,000 posters from the London Transport museum

- Posters of the Russian Civil War, 1918-1922 New York Public Library digital collection

- USSR posters Ben Perry's Flickr photoset with almost 1500 Soviet propaganda, advertising, theatre and movie posters from 1917-1991

- Psychedelic posters Andrew Olsen's collection of hundreds of psychedelic posters for gigs at The Fillmore and The Avalon

- Millie, Elena and Zbigniew Kantorosinski (1993). The Polish Poster: from Young Poland through the Second World War : Holdings in the Prints and Photographs Division, Library of Congress

- More than 33,000 political posters from around the world, primarily from the twentieth century, available online at the Hoover Institution Archives, Stanford University.