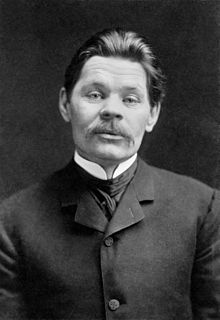

Maxim Gorky

Appearance

Aleksei Maksimovich Peshkov [Алексей Максимович Пешков] (28 March 1868 [16 March O.S. ] - 14 June 1936), known primarily by his pen name, Maxim Gorky [Максим Горький], was a Russian writer and socialist political thinker. He was nominated five times for the Nobel Prize in Literature.

Quotes

[edit]

- There's a little book I'm thinking of writing — "Swan Song" is what I shall call it. The song of the dying. And my book will be incense burnt at the deathbed of this society, damned with the damnation of its own impotence.

- Foma Gordeyev (1899) [also translated as The Man Who Was Afraid; the English music group Led Zeppelin would later name their record label "Swan Song".

- The good qualities in our soul are most successfully and forcefully awakened by the power of art. Just as science is the intellect of the world, art is its soul.

- Untimely Thoughts (1917-18) (original: Наиболее успешно и могуче будит в нашей душе ее добрые начала сила искусства. Как наука является разумом мира, так искусство — сердце его.)

- Everybody, my friend, everybody lives for something better to come. That's why we want respect for every man — who knows what's in him, why he was born and what he can do?

- The Lower Depths (1902)

- Some one has to be kind, girl — some one has to pity people! Christ pitied everybody — and he said to us: "Go and do likewise!" I tell you — if you pity a man when he most needs it, good comes of it. Why — I used to be a watchman on the estate of an engineer near Tomsk — all right — the house was right in the middle of a forest — lonely place — winter came — and I remained all by myself. Well — one night I heard a noise — thieves creeping in! I took my gun — I went out. I looked and saw two of them opening a window — and so busy that they didn't even see me. I yell: "Hey there — get out of here!" And they turn on me with their axes — I warn them to stand back, or I'd shoot — and as I speak, I keep on covering them with my gun, first on the one, then the other — they go down on their knees, as if to implore me for mercy. And by that time I was furious — because of those axes, you see — and so I say to them: "I was chasing you, you scoundrels — and you didn't go. Now you go and break off some stout branches!" — and they did so — and I say: "Now — one of you lie down and let the other one flog him!" So they obey me and flog each other — and then they began to implore me again. "Grandfather," they say, "for God's sake give us some bread! We're hungry!" There's thieves for you, my dear! [Laughs.] And with an ax, too! Yes — honest peasants, both of them! And I say to them, "You should have asked for bread straight away!" And they say: "We got tired of asking — you beg and beg — and nobody gives you a crumb — it hurts!" So they stayed with me all that winter — one of them, Stepan, would take my gun and go shooting in the forest — and the other, Yakoff, was ill most of the time — he coughed a lot . . . and so the three of us together looked after the house . . . then spring came . . . "Good-bye, grandfather," they said — and they went away — back home to Russia . . . escaped convicts — from a Siberian prison camp . . . honest peasants! If I hadn't felt sorry for them — they might have killed me — or maybe worse — and then there would have been a trial and prison and afterwards Siberia — what's the sense of it? Prison teaches no good — and Siberia doesn't either — but another human being can . . . yes, a human being can teach another one kindness — very simply!

- The character "Luka" in The Lower Depths (1902) English translation by Laurence Irving (1912)

- There — you say — truth! Truth doesn't always heal a wounded soul. For instance, I knew of a man who believed in a land of righteousness. He said: "Somewhere on this earth there must be a righteous land — and wonderful people live there — good people! They respect each other, help each other, and everything is peaceful and good!" And so that man — who was always searching for this land of righteousness — he was poor and lived miserably — and when things got to be so bad with him that it seemed there was nothing else for him to do except lie down and die — even then he never lost heart — but he'd just smile and say: "Never mind! I can stand it! A little while longer — and I'll have done with this life — and I'll go in search of the righteous land!" — it was his one happiness — the thought of that land. And then to this place — in Siberia, by the way — there came a convict — a learned man with books and maps — yes, a learned man who knew all sorts of things — and the other man said to him: "Do me a favor — show me where is the land of righteousness and how I can get there." At once the learned man opened his books, spread out his maps, and looked and looked and he said — no — he couldn't find this land anywhere . . . everything was correct — all the lands on earth were marked — but not this land of righteousness. The man wouldn't believe it. . . . "It must exist," he said, "look carefully. Otherwise," he says, "your books and maps are of no use if there's no land of righteousness." The learned man was offended. "My plans," he said, "are correct. But there exists no land of righteousness anywhere." Well, then the other man got angry. He'd lived and lived and suffered and suffered, and had believed all the time in the existence of this land — and now, according to the plans, it didn't exist at all. He felt robbed! And he said to the learned man: "Ah — you scum of the earth! You're not a learned man at all — but just a damned cheat!" — and he gave him a good wallop in the eye — then another one . . . [After a moment's silence.] And then he went home and hanged himself.

- The character "Luka" in The Lower Depths (1902) English translation by Laurence Irving (1912)

- One has to be able to count, if only so that at fifty one doesn't marry a girl of twenty.

- The Zykovs (1914)

- Processing the human raw material is naturally more complicated than processing lumber.

- If anyone want to become a socialist in a hurry, he should come to the United States.

- American Sketches

- It is quiet and peaceful here, the air is good, there are numerous gardens, and in them nightingales sing and spies lurk under the bushes.

- Letter to Anton Chekhov [1]

Quotes about Gorky

[edit]- It was typical of hundreds held throughout Italy. In no other country was sympathy with the victims of Tsarism so widespread. After 1905, when Maxim Gorki, already one of the world's most famous literary figures, was delegated to raise funds in the United States for the Russian victims, his total collections amounted to one-third of what I obtained among the Italian workers and peasants who lived under conditions which would have seemed unbearable to most American workers. Gorki's mission was marked with sensational incidents. He was refused admission to a New York hotel where he attempted to register with the Russian actress, Andreyeva, with whom he had been living for some time, and American conservatives started a vicious scandal-mongering campaign against him. A relationship which was accepted as a matter of course in Europe placed too much strain upon the American bourgeois conscience. Even Mark Twain joined the chorus against him, a chorus which was answered by the many radicals and intellectuals who rallied to his defence.

- Angelica Balabanoff My Life As a Rebel (1938)

- A time will come when people will forget Gorky’s works, but he himself will hardly be forgotten even in a thousand years.

- Anthon Chekhov[citation needed]

- Yevgeni Chirikov's play Yevrei (1904; Die Juden, 1904) was also an attack on antisemitism, as were the numerous short stories and newspaper articles by Vladimir Korolenko and Maxim Gorki, who warmly championed Russia's Jews, particularly the poor ones.

- "As an old revolutionist you must know that revolution is a grim and relentless task. Our poor Russia, backward and crude, her masses, steeped in centuries of ignorance and darkness, brutal and lazy beyond any other people in the world!" I gasped at his sweeping indictment of the entire Russian people. His charge was terrible, if true, I told him. It was also rather novel. No Russian writer had ever spoken in such terms before. He, Maxim Gorki, was the first to advance such a peculiar view, and the first not to put all the blame upon the blockade, the Denikins and Kolchaks. Somewhat irritated, he replied that the "romantic conception of our great literary genuises" had entirely misrepresented the Russian and had wrought no end of evil. The Revolution had dispelled the bubble of the goodness and naïveté of the peasantry. It had proved them shrewd, avaricious, and lazy, even savage in their joy of causing pain. The rôle played by the counter-revolutionary Yudeniches, he added, was too obvious to need special emphasis. That is why he had not considered it necessary even to mention them, nor the intelligentsia, which had been talking revolution for over fifty years and then was the first to stab it in the back with sabotage and conspiracies. But all these were contributory factors, not the main cause. The roots were inherent in Russia's brutal and uncivilized masses, he said. They have no cultural traditions, no social values, no respect for human rights and life. They cannot be moved by anything except coercion and force. All through the ages the Russians had known nothing else.

- Emma Goldman Living My Life (1931)

- Ilyich (Lenin) liked Gorky the man, with whom he had become closely acquainted at the London Congress of the Party, and he liked Gorky the artist; he said that Gorky the artist was capable of grasping things instantly. With Gorky he always spoke very frankly.

- I heard Gorky speak before a big union meeting. I could not understand what he said, but I could see that he was inspired by the crowd and the occasion, that he loved the workers deeply, and that they loved him. He looked as I thought he would, like a peasant. When I met him afterwards, he asked me about America, and whether we were still reading his books. I told him how much his Mother meant to me, and to many other Americans.

- Ella Reeve Bloor We Are Many: An Autobiography (1940)

- "proletarian" origins became a valuable commodity in Russian literature following Maxim Gorky's forceful autobiography

- Ruth Wisse The Modern Jewish Canon (2000)

External links

[edit]- Brief biography

- Gorky Archive at Marxists.org

- "Anton Chekhov: Fragments of Recollections" by Maxim Gorky