Lucia Dacome

University of Toronto, IHPST, Faculty Member

- History of Medicine and the Body, History of Science, Mediterranean Studies, History of Slavery, Gender History, Women's History, and 6 moreEarly modern cross-cultural encounters, Material Culture Studies, Eighteenth Century History, Gender and Sexuality, History of the Mediterranean, and Early Modern Historyedit

This paper considers the entanglements of slavery, medicine, and natural inquiry in eighteenth-century Tuscany. In particular, it considers the stories of enslaved individuals from the Muslim Mediterranean world who participated in the... more

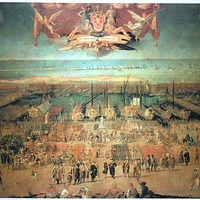

This paper considers the entanglements of slavery, medicine, and natural inquiry in eighteenth-century Tuscany. In particular, it considers the stories of enslaved individuals from the Muslim Mediterranean world who participated in the Tuscan world of medical and natural knowledge.

Research Interests:

This paper considers the histories of Ottoman captives who participated in the worlds of medical and natural knowledge in early modern Tuscany. It focuses on spaces of encounter between this community of enslaved individuals and the local... more

This paper considers the histories of Ottoman captives who participated in the worlds of medical and natural knowledge in early modern

Tuscany. It focuses on spaces of encounter between this community of enslaved individuals and the local free population.

Tuscany. It focuses on spaces of encounter between this community of enslaved individuals and the local free population.

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

This paper focuses on the health-related spaces and practices that developed alongside the creation of a Bagno that housed a large community of enslaved individuals in the Tuscan port city of Livorno.

Research Interests:

Malleable Anatomies examines the early stages of the practice of anatomical modelling. It investigates the ‘mania’ for anatomical displays that swept the Italian peninsula in the mid-eighteenth century, and traces the fashioning of... more

Malleable Anatomies examines the early stages of the practice of anatomical modelling. It investigates the ‘mania’ for anatomical displays that swept the Italian peninsula in the mid-eighteenth century, and traces the fashioning of anatomical models as important social, cultural, and political as well as medical tools. Anatomical models offered special insights into the inner body. Being coloured, soft, and malleable, they fostered anatomical knowledge in delightful ways. But how did anatomical models inscribe and mediate bodily knowledge? How did they change the way in which anatomical knowledge was created and communicated? And how did they affect the lives of those involved in their production, display, viewing, and handling? Examining the circumstances surrounding the making and early viewing of anatomical displays in Bologna, Naples, and Palermo, Malleable Anatomies addresses these questions by reconstructing how anatomical modelling developed at the intersection of medical kno...

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

Research Interests:

The so-called anatomical machines of the Prince of Sansevero, on display at the Museo Capella Sansevero in Naples, are two anatomical models, of a man and a woman, which depict the system of blood vessels in the human body. They were made... more

The so-called anatomical machines of the Prince of Sansevero, on display at the Museo Capella Sansevero in Naples, are two anatomical models, of a man and a woman, which depict the system of blood vessels in the human body. They were made by the anatomist Giuseppe Salerno in the mid-18 th century and presented as the result of anatomical preparations based on a technique known as "anatomical injection" (injection of embalming substances in cadavers). Sansevero's anatomical machines have gradually become the subject of a legend, according to which the models were the outcome of an operation of human vivisection in which a woman and a man were killed through the injection of embalming substances in their blood vessels. Due to lack of written documentation on the early history of the anatomical machines, controversy continues about how they were actually made. This project tried to address this controversy by combining examination and instrumental analysis of their raw ma...

... In Ephraim Chambers's Cyclopaedia (1728), for instance, Sanctorius's chair was presented under the entry for 'weighing' as a device aimed at controlling the ingestion of food: “a Machine contrived by Sanctorius to... more

... In Ephraim Chambers's Cyclopaedia (1728), for instance, Sanctorius's chair was presented under the entry for 'weighing' as a device aimed at controlling the ingestion of food: “a Machine contrived by Sanctorius to determine the Quantity of Food taken at a Meal, and to warn the ...

Research Interests:

This essay examines the historical fortunes of an image that throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries became a landmark of the medical doctrine and practice of static medicine advanced by the physician Santorio Santorio... more

This essay examines the historical fortunes of an image that throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries became a landmark of the medical doctrine and practice of static medicine advanced by the physician Santorio Santorio (1561-1636). The image depicted a man sitting on a large Roman steelyard, which allowed the weighing of bodily discharges and gave guidance on the intake of food. Well into the eighteenth century, the image of the weight-watching man accompanied Santorio's work on the art of static medicine and, most likely, contributed to its success. It appeared in a variety of medical works and navigated across competing medical theories and different medical genres, while remaining largely unscathed. This essay explores the success and the historical agency of this image. Focusing on the history of its copies and variants, it investigates how the image came to symbolize the attempt to transform dietetics into an experimental practice, and accordingly preserve its pivotal significance in the medical world.

Research Interests:

This paper investigates the debate on the nature of dreams that took place in eighteenth-century Britain. Focusing on the increasingly popular view of the time that perfect sleep was sleep without dreams, it examines the medicalization of... more

This paper investigates the debate on the nature of dreams that took place in eighteenth-century Britain. Focusing on the increasingly popular view of the time that perfect sleep was sleep without dreams, it examines the medicalization of dreaming that developed alongside the conceptualization of dreams as instances of mental derangement. At the end of the seventeenth century, John Locke had likened dreaming to madness and drunkenness, and characterized it as a disturbance of the self. In the course of the eighteenth century, physicians, religious preachers, champions of politeness and moral philosophers all provided competing accounts of the doubling of consciousness which was incidental to dreaming. This paper situates their attempts in the context of re-assessment of the authorities that defined what constituted credible and reliable thinking. It does so by drawing attention to the body as one of the crucial sites in which changing attitudes towards dreaming were discussed and negotiated.