VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

MARCH 2012

http://www.nagc.org/

Counseling and Guidance

N

E

W

S

L

E

T

T

E

R

Giftedness is not a matter of degree but of a different quality of experiencing: vivid, absorbing, penetrating,

encompassing, complex, commanding – a way of being quiveringly alive.

- Michael Piechowski

A TRIANNUAL NEWSLETTER

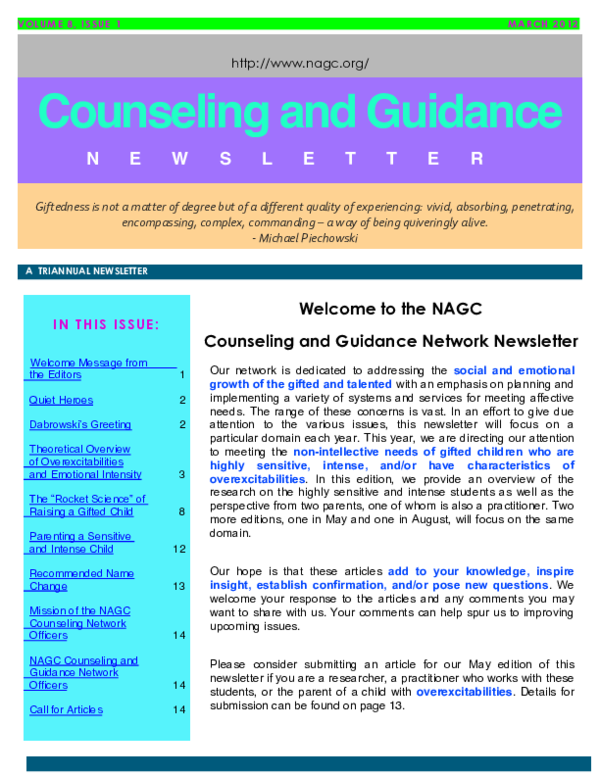

Welcome to the NAGC

IN THIS ISSUE:

Counseling and Guidance Network Newsletter

Welcome Message from

the Editors

1

Quiet Heroes

2

Dabrowski’s Greeting

2

Theoretical Overview

of Overexcitabilities

and Emotional Intensity

3

The “Rocket Science” of

Raising a Gifted Child

8

Parenting a Sensitive

and Intense Child

Our network is dedicated to addressing the social and emotional

growth of the gifted and talented with an emphasis on planning and

implementing a variety of systems and services for meeting affective

needs. The range of these concerns is vast. In an effort to give due

attention to the various issues, this newsletter will focus on a

particular domain each year. This year, we are directing our attention

to meeting the non-intellective needs of gifted children who are

highly sensitive, intense, and/or have characteristics of

overexcitabilities. In this edition, we provide an overview of the

research on the highly sensitive and intense students as well as the

perspective from two parents, one of whom is also a practitioner. Two

more editions, one in May and one in August, will focus on the same

domain.

12

Recommended Name

Change

13

Mission of the NAGC

Counseling Network

Officers

14

NAGC Counseling and

Guidance Network

Officers

14

Call for Articles

14

Our hope is that these articles add to your knowledge, inspire

insight, establish confirmation, and/or pose new questions. We

welcome your response to the articles and any comments you may

want to share with us. Your comments can help spur us to improving

upcoming issues.

Please consider submitting an article for our May edition of this

newsletter if you are a researcher, a practitioner who works with these

students, or the parent of a child with overexcitabilities. Details for

submission can be found on page 13.

�VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

S

E

Q

2

U

O

I

A

MARCH 2012

C

L

U

B

2

QUIET HEROES

Many of the people working with the social and emotional needs of gifted students have limited

exposure because much of what they do is confidential. Their efforts are usually carried out

inconspicuously at an individual or small group level. Many of us know people whose commitment to

meeting the social and affective needs of children shows remarkable dedication, enormous energy,

impressive competence, and persistent compassion.

If you know of such a person, consider nominating him or her for recognition as a Quiet Hero. Send

us a short biography along with how the person exudes the qualities of commitment, energy,

competence, and compassion. Stories or anecdotes allowed by confidentiality and respect for

privacy that support how your nominee excels in working with gifted children will also be helpful.

Send your submissions to nagc.cg.newsletter@gmail.com. We will recognize Quiet Heroes in our

August newsletter. We look forward to sharing their stories.

Be greeted psychoneurotics!

For you see sensitivity in the insensitivity of the world, uncertainty

among the world's certainties.

For you often feel others as you feel yourselves.

For you feel the anxiety of the world, and

its bottomless narrowness and self-assurance.

For your phobia of washing your hands from the dirt of the world,

for your fear of being locked in the world’s limitations. for your fear

of the absurdity of existence.

For your subtlety in not telling others what you see in them.

Poem by Kazimierz Dabrowski

Dabrowski, K. (1972). Psychoneurosis is not

an illness, London: GRYF Publications.

For your awkwardness in dealing with practical things, and

for your practicalness in dealing with unknown things,

for your transcendental realism and lack of everyday realism,

for your exclusiveness and fear of losing close friends,

for your creativity and ecstasy,

for your maladjustment to that "which is" and adjustment to that which "ought to

be", for your great but unutilized abilities.

For the belated appreciation of the real value of your greatness

which never allows the appreciation of the greatness

of those who will come after you.

For your being treated instead of treating others,

for your heavenly power being forever pushed down by brutal force;

for that which is prescient, unsaid, infinite in you.

For the loneliness and strangeness of your ways.

Be greeted!

�VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

S

E

Q

3

U

O

I

A

MARCH 2012

C

L

U

B

3

Theoretical Overview of Overexcitabilities and Emotional Intensity

by Merzili Villanueva

PhD Student, University of Connecticut

Doctoral Research Assistant, Neag Center for Gifted Education and Talent Development

The lasting purpose of the Counseling and Guidance Network’s newsletter is to build advocacy for

the psychosocial needs of gifted individuals. This year, we have chosen to focus on the role of

Dabrowski’s Theory of Positive Disintegration (TPD) and overexcitabilities (OEs) in

understanding and nurturing the emotional intensities and sensitivities of gifted individuals along the

developmental lifespan. The following article serves as an introduction to the theory for those

unfamiliar with Dabrowski’s work and the research that has followed.

Researchers and practitioners in the field of gifted education and counseling have used Kazimierz

Dabrowski’s (1902-1980) Theory of Positive Disintegration (TPD) and concept of overexcitabilities

(OEs) to inform parents, educators, counselors, and the general public about how the intensities

and sensitivities of gifted individuals manifest and can be nurtured for emotional growth (e.g.,

Daniels & Piechowski, 2009; Mendaglio, Tillier, Finlay, Michelle-Pentelburry, & Dodd, 2002).

Dabrowski—a Polish psychiatrist, psychologist, and professor—developed the concepts in TPD

from research data and observations in his clinical and everyday experiences. Although Dabrowski

(1964, 1972) has described TPD as a theory of psychological personality development, he and

other researchers have also maintained that it is one of emotional development (e.g., Gross, Rinn, &

Jamieson, 2007; Miller, Silverman, & Falk, 1994; Mróz, 2009; Silverman, 1992).

Researchers and counselors have emphasized the critical need to attend to the affective concerns

of gifted individuals and have advocated for the practical application of TPD (e.g., Silverman,

1992, 1993; Sisk, 2008). Some have proposed using OEs and Dabrowskian levels of development

to supplement common identification methods for giftedness (e.g., Ackerman, 1997; Bouchard,

2004; Lee & Olszewski-Kubilius, 2006; Piechowski, 1979), and providing differentiated educational

services to support self-actualization (Sisk, 2008). Others have proposed using OEs and

developmental potential (DP), as a means of broadening the conception of giftedness (Piechowski,

1986; Yakmaci-Guzel & Bogazici, 2006). Counselors and psychologists have applied OEs and

Dabrowski’s TPD in their work with gifted children, their parents, and schools to provide appropriate

interventions and accommodations (Daniels, 2009; Jackson & Moyle, 2009; Mahoney, 1997;

Peterson, 2003). Some have addressed misdiagnosis of pathological conditions such as

Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder (OCD), and

Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD) (e.g., Mika, 2002, 2006; Webb, Amend, Webb, Goerss,

Beljan, & Olenchak, 2005);

perfectionism, (Schuler, 2001, 2002; Silverman, 2009);

depression (Neihart, 2002); and,

suicide (Gust-Brey & Cross, 1999).

Dabrowski and The Gifted

Overexcitabilities

Dabrowski introduced the concept of overexcitability to describe five forms of “heightened ways of

processing experiences and percieving the world (Mendaglio & Tillier, 2006, p. 69).

�VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

S

E

Q

4

U

O

I

A

MARCH 2012

C

L

U

B

4

Translated from Polish, OE means superstimulated (Piechowski, 1999). As noted in the

following descriptions, individuals can express OEs in both positive and negative ways, which can

be considered both potential benefits and challenges (adapted from Piechowski, 1979).

psychomotor- surplus of energy; enthusiasm; restlessness for organizing and taking

action; delinquent behavior; compulsive talking; impulsive actions; workaholism;

competitiveness; nervous physical habits (nail biting, toe tapping, leg shaking).

sensual- heightened awareness and reactions to seeing, smelling, tasting, touching,

hearing; overeating; expression of emotional tension through sexual arousal and

behaviors; buying sprees.

intellectual- burning curiosity; rage to know and master; urge to ask probing

questions; tendency for introspection and deep analysis; ability to remain intellectually

engaged with a task for an extended period of time; facility with synthesis and

understanding generalizations.

imaginational- animistic and magical thinking; tendency to daydream and fantasize,

and create rich inner worlds and have imaginary friends; likeness for image and

metaphor; elaborate daydreams and fantasies; strong ability to visualize; fear of future

events.

emotional- able to easily gauge and identify with others’ feelings;; has deep-felt and

complex range of emotions, including extremes of positive and negative emotions

(e.g., anxiety, depression, nervousness, guilt, shame, pride, love, empathy,

compassion); physiological expressions of emotional tension; strong attachment to

people, places, and things; difficulty adjusting to new environments.

All individuals experience OEs, but the gifted experience them in a quantitatively and

qualitatively different way than the non-gifted. Dabrowski contended that OEs were biological

and that their intensity, frequency, and duration in the individual could be used as measures of

developmental potential (DP), or the highest level of development an individual could achieve

given the optimal conditions (Miller & Silverman, 1987; Piechowski, 1975; Piechowski &

Colangelo, 1982; Piechowski & Cunningham, 1985; Piechowski & Miller, 1995). He used this

concept to refer to a constellation of psychological features, associated with advanced

personality development: special abilities and talents; intelligence; psychomotor, sensual,

intellectual, imaginational, and emotional overexcitabilities;; and a strong will to realize one’s

potential and personality ideal (Mendaglio & Tillier, 2006; Piechowski & Miller, 1995).

Dabrowski found emotional, intellectual, and imaginational to be the most pronounced,

and necessary for advanced development, although other studies have found emotional,

imaginational, and psychomotor to be the dominant OEs for some gifted individuals (e.g.,

Ackerman, 1997; Gallagher, 1986; Schiever, 1985). Dabrowskians have argued that DP is

an indicator of giftedness (Ackerman, 1997; Piechowski, 1979), and have chosen OEs to be

the concept of TPD most applied to giftedness and gifted education (Mendaglio & Tillier,

2006). Where Piaget’s and Erikson’s theories of human development are suitable for the general

population, Dabrowski’s TPD is more relevant for understanding giftedness from a

developmental perspective (Aronson, 1964; Mendaglio et al., 2002).

Theory of Positive Disintegration

Dabrowski’s theory emerged from his studies of gifted and non-gifted individuals, particularly clinical

patients, school children, artists, writers, and religious exemplars. He found that these individuals

�VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

S

E

Q

5

U

O

I

A

MARCH 2012

C

L

U

B

5

experienced similar developmental patterns and characteristics, which he believed to be

positive tenets of personality growth. Among these patterns are periods of disintegration,

which Dabrowski has defined as "disharmony within the individual and in his adaptation to the

external environment" (Aronson, 1964, p. 139). He believed that individuals are instinctually drawn

toward autonomous functioning as an ideal and moral being. Higher levels of

development are attained when the individual experiences dissatisfaction of oneself, and

a subsequent unavoidable

collapse

of the existing personality structure, which is

accompanied by conflict, anxiety, psychoneurosis, and psychosis—a period of positive

disintegration. Although these seem to be negative experiences, they usually work in favor of the

individual’s development as the disintegrative process reverses towards integration, which

includes evolution, mental well-being, and ability to function effectively independently and

within surrounding environments. This secondary integration occurs at a higher level of

development than the one previous. Negative disintegration can also occur if the

environmental situations are unfavorable.

Levels of Personality Development

Dabrowski outlined five levels of development, which an individual can vacillate

in between depending on one’s current disintegrative or integrative period. At Level I:

Primary Integration, the individual experiences little inner conflict, and lack of a stable value

system and realization of goals. Occurrence of external conflicts exists. At Level

II: Unilevel Disintegration, internal conflicts appear, but are not resolved by deliberate

choice. Behavior conforms to external standards with little reflection. Level III and IV:

Organized Multilevel Disintegration is called the inner psychic milieu (Piechowski, 1974). The

individual experiences feelings of shame, guilt, discouragement, and great dissatisfaction with

oneself, recognizing “what is” and envisioning “what ought to be”. Dabrowski noted

this

experience

to

be positive

maladjustment—experiencing

great

pain

while

simultaneously growing into one’s ideal self. Although unilevel functioning is still

present, the individual makes a conscious effort to progress toward his or her personality

ideal. Finally, at Level V: Secondary Integration occurs. The individual is free from internal

conflicts, and “what is” is replaced with “what ought to be” (Piechowski, 1975, pp. 260-262).

Dabrowski believed certain conditions must be present at each level of development, and that these

conditions

would

influence

behavior.

The

first

group

of

factors

represents

hereditary influences (Level I), the second group represents environmental influences (Level II,

III, and IV), and the third group represents autonomous inner processes (Level V)

(Piechowski, 1975). Dabrowski (1964) emphasized the important role of the third factor—

the autonomous inner processes—in multilevel disintegration. The individual selects

transformation over hereditary and environmental forces. He noted that the third factor arises in

certain individuals during periods of stress and transition, such as puberty and adolescence.

Dabrowski’s concepts of OEs and DP have been outlined within the context of his theory

for the purpose of understanding the proceeding discussions regarding OEs in gifted

individuals. Though researchers have indicated that OEs are markers of DP, they warn against

isolating OEs from TPD, and rather advocate for holistic application of TPD (Miller &

Silverman, 1987; Piechowski, 1975; Piechowski & Colangelo, 1984; Piechowski & Cunningham,

1985; Piechowski & Miller, 1995).

�VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

S

E

Q

6

U

O

I

A

MARCH 2012

C

L

U

B

6

References

Ackerman, C. M. (1997). Identifying gifted adolescents using personality characteristics:

Dabrowski's overexcitabilities, Roeper Review, 19, 229-236.

Aronson, J. (1964). In J. Aronson (Ed.), Positive disintegration (p. 139). Boston, MA: Little Brown.

Bouchard, L. L. (2004). Instrument for the measure of Dabrowskian overexcitabilities to identify

gifted elementary students, Gifted Child Quarterly, 48, 339-350.

Dabrowski, K. (1964). Positive disintegration. Boston, MA: Little, Brown.

Dabrowski, K. (1972). Psychoneurosis is not an illness. London, England: Gryf.

Dabrowski, K., & Piechowski, M. M. (1977). Theory of levels of emotional development: From

primary integration to self- actualization (Vol. 2). Oceanside, NY: Dabor Science.

Daniels, S., & Piechowski, M. M. (2009). Living with intensity. Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press.

Gallagher, S. A. (1986). A comparison of the concept of overexcitabilities with measures of creativity

and school achievement in sixth grade students. Roeper Review, 8, 115-119.

Gross, C. M., Rinn, A. N., & Jamieson, K. M. (2007). The relationship between gifted adolescents’

overexcitabilities and self-concepts: An analysis of gender and grade level. Roeper Review,

29, 240-248.

Gust-Brey, K., & Cross, T. (1999). An examination of the literature base on the suicidal behaviors of

gifted students. Roeper Review, 22, 28-35.

Jackson, P. S., & Moyle, V. F. (2009). Integrating the intense experience: counseling and clinical

applications. In S. Daniels & M. Piechowski (Eds.), Living with intensity (pp. 57-71).

Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press.

Lee, S., & Olszewski-Kubulius, P. (2006). Comparisons between talent search students qualifying

via scores on standardized tests and via parent nomination. Roeper Review, 28, 157-166.

Mahoney, A. S. (1998). In search of the gifted identity: From abstract concept to workable

counseling constructs. Roeper Review, 20, 222-226.

Mendaglio, S. (Ed.). (2008). Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration. Scottsdale, AZ: Great

Potential Press.

Mendaglio, S., & Tillier, W. (2006). Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration and giftedness:

Overexcitability research findings. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 30, 68-87.

Mendaglio, S., Tillier, W., Finlay, L., Michelle-Pentelbury, R., & Dodd, A. (2002). Special issue:

Dabrowski’s theory of positive disintegration and gifted education. Journal of the Gifted and

Talented Education Council of the Alberta Teachers’ Association—AGATE, 15(2), 2-46.

Mika, E. (2002). Gifted children and overexcitabilities and a preliminary clinical study. In N. Duda,

Ed.), Positive disintegration: The theory of the future. 100th Dabrowski anniversary program

on the man, the theory, the application and the future (pp. 323-336). Fort Lauderdale, FL:

Fidlar Doubleday.

Mika. E. (2006). Giftedness, ADHD, and overexcitabilities: The possibilities of misinformation.

Roeper Review, 28, 237-242.

Miller, N. B., & Silverman, L. K. (1987). Levels of personality development. Roeper Review, 9, 221.

Miller, N. B., Silverman, L. K., & Falk, R. E. (1994). Emotional development, intellectual ability, and

gender. Journal for the Education of the Gifted, 18, 20-38.

Mróz, A. (2009). Theory of positive disintegration as a basis for research on assisting development.

Roeper Review, 31, 96-102.

Neihart, M. (2002). Gifted children and depression. In M. Neihart, S. M. Reis, N. M. Robinson, & S.

M. Moon, (Eds.) The social and emotional development of gifted children: What do we know?

(pp. 93-101). Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Peterson, J. S. (2003). An Argument for proactive attention to affective concerns of gifted

�VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

S

E

Q

7

U

O

I

A

MARCH 2012

C

L

U

B

7

adolescents. Journal of Secondary Gifted Education, 14, 62-70.

Piechowski, M. M. (1974). Two developmental concepts: Multilevelness and developmental

potential. Counseling and Values, 18, 86-93.

Piechowski, M. M. (1975). A theoretical and empirical approach to the study of development.

Genetic Psychology Monographs, 92, 231-297.

Piechowski, M. M. (1979). Developmental potential. In N. Colangelo, & R. T. Zaffran (Eds.), New

voices in counseling the gifted (pp.25-57). Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt Publishing Company.

Piechowski, M. M. (1986). The concept of developmental potential. Roeper Review, 8, 190-197.

Piechowski, M. M. (1999). Overexcitabilities. In M. A. Runco & S. R. Pritzker (Eds.), Encyclopedia

of Creativity (Vol. 2, pp. 325-334). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Piechowski, M. M., Colangelo, N. (1984). Developmental potential of the gifted. Gifted Child

Quarterly, 28, 80-88.

Piechowski, M. M., & Cunningham, K. (1985). Patterns of overexcitability in a group of artists.

Journal of Creative Behavior, 19, 153-174.

Piechowski, M. M., & Miller, N. B. (1995). Assessing developmental potential in gifted children: A

comparison of methods. Roeper Review, 17, 176-188.

Schiever, S. W. (1985). Creative personality characteristics and dimensions of mental functioning

in gifted adolescents. Roeper Review, 7, 223-226.

Schuler, P. A. (2001). Perfectionism and the gifted adolescent. Journal of Secondary Gifted

Education,11, 183-196.

Schuler, P. A. (2002). Perfectionism in gifted children and adolescents. In M. Neihart, S. M. Reis,

N. M. Robinson, & S. M. Moon, (Eds.) The social and emotional development of gifted

children: What do we know? (pp. 81-91). Waco, TX: Prufrock Press.

Silverman, L. K. (1992). Counseling the gifted individual. Counseling and Human Development, 25,

1-16.

Silverman, L. K. (1993). Counseling the gifted and talented. Denver, CO: Love.

Silverman, L. K. (2009). Petunias, perfectionism, and levels of development. In S. Daniels & M.

Piechowski (Eds.), Living with intensity (pp. 145-164). Scottsdale, AZ: Great Potential Press. Sisk,

D.(2008). Engaging the spiritual intelligence of gifted students to build awareness in the

classroom. Roeper Review, 30, 24-30.

Webb, J. T., Amend, E. R., Webb, N. E., Goerss, J., Belijan, P., & Olenchak, F. R. (2005).

Misdiagnosis and dual diagnosis of gifted children and adults. Scottsdale, AZ: Great

Potential Press.

Yakmaci-Guzel, B., & Akarsu, F. (2006). Comparing overexcitabilities of gifted and non-gifted 10th

grade students in Turkey. High Ability Studies, 17, 43–56.

There is a goldmine of hidden creativity in each one of these children, which can

blossom into spiritual, emotional, creative and scientific growth. We need to build

bridges

theofinner

world

of the individual

andofthe

outer

world of

society,

There

is between

a goldmine

hidden

creativity

in each one

these

children,

which

can

so that knowledge,

thoughts

and creative

emotionsand

canscientific

flow freely

between

blossom

into spiritual,

emotional,

growth.

We them.

need to build

bridges between the inner world of the individual and the outer world of society, so

that knowledge, thoughts and emotions can flow freely between them.

Annemarie Roeper

– Annemarie Roeper

7

�VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

S

E

Q

8

U

O

I

A

MARCH 2012

C

L

U

B

8

The “Rocket Science” of Raising a Gifted Child

by Christine Turo-Shields, ACSW, LCSW, LCAC

T-ball starts when children are about 3 or 4 years old. Parents of a t-ball players look forward to

watching their children fumble and frolic on the field, throwing and catching their mitts into the air as

the game is going on, spinning or sitting in on the field out of sheer excitement or boredom for the

game of t-ball. Focus is nonexistent, save their focus on the butterfly flitting around or the clover

patch that they just discovered as they look for the lucky one with four leaves. Now, introduce the

ball into play and you will have outtakes funny enough to submit to America’s Funniest Videos –

players who don’t even notice that the ball is in play, let alone right in front of their mitt. In those

cases, they charge the ball, overrun it, but have the good fortune to get to it, only to overthrow it to

the wrong base. We parents don’t care, we still cheer in a wild frenzy, making our children think they

are the next great A-Rod, all the while cringing and laughing at their obvious developmental

inadequacies of their age.

Not Joshua’s parents. When my daughter played t-ball, there was this little boy named Joshua on

her team. You could easily pick out Joshua because he was always in the ready stance position,

alert to only the ball as the batter painfully missed the coach-pitches . . . so out comes the t-ball

stand, but still another “swing & a miss.” That didn’t distract Joshua whose eyes were glued to the

ball. From the moment that the bat hit the ball, Joshua responded on instinct, getting to the ball first

nearly each and every time, even though he was playing third base and the ball was dribbled down

the first base line. Game after game he played with such natural ability that it created some ire

among his fellow players, including my strong-willed Sarah. Sarah had the desire and will to get to

the ball first, but not the ability, not like Joshua. Joshua always got to it first – one day, Sarah got so

mad she burst into tears. Couldn’t everyone see the injustice? Couldn’t everyone see that Joshua

was being a ball hog on the field? Couldn’t somebody do something to stop him or slow him down?

Joshua’s parents would make feeble attempts to temper his enthusiasm, to try to calm his gazellelike moves across the field, but he wouldn’t have it. His body just responded to every aspect of the

game, accurately. He was truly in a league of his own. Like Dash in The Incredibles, no one was

going to slow him down. They watched every game cringing, but not out of laughter like us other

parents, but out of struggle – the struggle of watching their child try to restrain himself and “play

nice” when it went against every bone in his body, against every aspect of genetic hardwiring

running through him.

At the end of the season, I talked to Joshua’s parents about his obvious and amazing athletic

giftedness. They apologized – they knew he loved the sport and was good at it, just didn’t realize he

was that far advanced from his peers. In total admiration of his ability, I encouraged them to

consider a competitive league for their 4 year old son, playing with those whose talent and ability

matched his. Watching Joshua on the field one could really envision the next A-Rod.

Profound athletic talent is hard to miss, and catching the wave of excitement at a child’s success

comes naturally to us – it’s as American as apple pie. Michael Phelps’ amazing natural talent and

ability was so obvious that he started training with a top swim coach at 11 years old and he began

training for the Olympics when he was 12 years old. Imagine his mother’s joy and excitement; think

�VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

S

E

Q

9

U

O

I

A

MARCH 2012

C

L

U

B

9

to your own experiences of what it was like for you as a child . . . rocket science and assorted

Brainiac concepts may also have been the norm for you as well.

In third grade, it seemed natural for me to know how to spell antidisestablishmentarianism, which, at

that time, was the longest word in the English dictionary. At 2 years of age, our son developed a

fascination with mechanical things – he loved the merry-go-round best because he could study the

rotations of the gear mechanisms that made it move. He threw fits if I did not take him downstairs to

do laundry . . . not because he wanted to help, but because he was mesmerized by the rotation of

the washer and resulting spill of water into the sump pump. When he went to visit friends and family,

his greeting was an inquiry, “Do you have a pedestal or submersible sump pump?” And that

question was quickly followed up with “Can I see it?” He was so well-studied on the cycle of the

sump pump that when 3 years old, he warned us that it was not cycling correctly – unfortunately, we

did not heed his warning, and the night we had a babysitter so we could go on a date, our sump

pump overflowed and flooded our basement. Lesson learned – the kid knew what he was talking

about.

Our son was the easily identified Brainiac child – just a brief conversation confirmed intelligence,

highlighted by advanced vocabulary, abstract thinking and a sarcastic wit. Our daughter’s

intelligence manifested much differently – my husband even questioned why IQ test her (the results

quelled his doubts). Research shows that girls with older gifted brothers are IQ tested at significantly

lower rates – sadly, we often miss the intelligence of our girls. My daughter has always been very

relational in her thinking. As a preschooler, she would cluster everything in terms of relationships,

even lining up quarters, nickels, pennies & dimes and giving them attributes of family members

based on size (i.e. Daddy was the quarter, Mommy was the nickel, and so on). At a very young age,

her deep empathy and supersensitivity was profound to witness as she would lament about the

plight of animals and poor people when sensing any type of injustice. She was hysterically crying as

she left me a voicemail one afternoon – I thought something tragic had happened. When I called her

back and could eventually decipher what she was saying between sobs, her angst was due to

watching one of those heart-wrenching commercials about puppy mills. That was tragic to her. She

wailed during the movie, Eight Below, when one of the dogs died. At the end of the movie, I asked

her what she thought. She said “It was a great movie, but I never want to see it again.”

As a parent and professional working with gifted and profoundly gifted kids, my perspective is a

unique one. Raising my children has been both “delightful and draining.” Gifted kids are special

needs kids on the other end of the IQ spectrum. Asynchrony rules their lives, and challenges our

lives as parents! Our precocious cherubs may have the vocabulary of a 16 year old, the passion for

world peace like a 34 year old, and then meltdowns and outbursts like a 2 year old . . . all at a ripe

young chronological age of maybe 6 or 7. It’s hard to tell them to “act their age” because their age is

so variable. They are often exhausting and frustrating. It is important to remember that genetics

plays a big part in this (they don’t lick it off the lead in the paint) . . . likely you were as exhausting

and frustrating to those who tried to parent and teach you as a child.

Dabrowski identifies five "overexcitabilities," or "supersensitivities," which manifest in the

gifted population: psychomotor, sensual, emotional, intellectual, and imaginational. Gifted children

�VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

S

E

Q

10

U

O

I

A

C

MARCH 2012

L

U

B

1

0

tend to have more than of these intensities, although one is usually dominant. Learning how to

manage these OE's becomes the balancing act, and survival skill, for gifted kids and their parents.

It's the blessing and the burden throughout life.

So the rocket science of parenting becomes how to feed a gifted child, especially in a society that

seeks to marginalize intellectual giftedness. First of all, don’t apologize for your child’s giftedness.

It’s in the hardwiring – it is what it is. Now, the question becomes what to do.

I’ve had many conversations with adults who judge that parents of gifted children push their kids.

Anyone who has walked in our shoes knows better. We are just struggling to keep up with them,

finding the right nourishment to satiate their insatiable hunger and thirst – their desire to learn more,

absorb all they can intellectually, connect with others like them, express their deepest emotions,

experience knowledge in a way we may never understand, and the list goes on.

Attending the NAGC Conference in Indianapolis 2003 was the entre’ into the gifted world for my

husband and me. For the first time, we felt normal – there were other parents like us who simply

wanted to feed their gifted kids. I have learned a lot both personally and professionally since that

first conference, mostly that we parents of gifted are not unlike our gifted kids. We, too, want to

learn, absorb, connect, express and experience.

For parents just starting this journey, here are some of my top picks that I always professionally

recommend:

Read Guiding the Gifted Child by James Webb & Stephanie Tolan – it’s an oldie, but

a goodie. It was the first book that I read which validated my journey and began to shed

light on the path of what to do for my kids.

Get your child IQ tested (request an IQ and an achievement test) – we know they are smart,

but it is valuable to know how smart. Many schools do not typically have a favorable.

Download the pdf, A Nation Deceived –a vital document for any parents of a gifted kid, as it

highlights the acceleration options and dispels the myths surrounding acceleration.

IQ testing also opens doors to resources such as Mensa (top 2% IQ), the Davidson Institute

for Talent Development (top 1% IQ), talent searches, etc – explore these for your child.

Traditional schools are the only place where kids are grouped by age rather than interest.

Gifted children need to be with intellectual peers, not just age-mates.

Embrace the parental mindset “Advocate, don’t alienate.” This is critical with schools,

programs, and adults who are involved in your child’s life. We want to open doors for

opportunities in their lives as we teach our kids to navigate life and create a meaningful life for

themselves.

Finding the people and places where intelligence is valued and

appreciated becomes our life’s journey. There are others who desperately

long to find a place for their children to belong and thrive. We are out

here –many of us have found the place where rocket science is the

norm and not the exception! Welcome – it’s a delightful and draining

ride!

10

�VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

S

E

Q

11

U

O

I

A

C

MARCH 2012

L

U

B

1

1

Christine Turo-Shields, ACSW, LCSW, LCAC personally & professionally knows the world of the

gifted. . . raising 2 gifted children and working with hundreds more in her counseling practice. As a

community expert in the GT/HA world, she has consulted with multiple Indianapolis school districts

on case consultations regarding gifted students as well as conducted and coordinated numerous

trainings and presentations for educators and parents. She has been an integral part in the

development of the Gifted Family Program for Central Indiana Mensa – a program so successful that

it won the American Mensa Gifted Children Program Award in July 2010. She is the co-owner of

Kenosis Counseling Center, Inc in Greenwood, IN. She can be reached at

christine@kenosiscenter.com or through the website at www.kenosiscenter.com

"The truly creative mind in any field

is no more than this: A human

creature born abnormally,

inhumanly sensitive. To him . . .

a touch is a blow,

a sound is a noise,

a misfortune is a tragedy,

a joy is an ecstasy,

a friend is a lover,

a lover is a god,

and failure is death.

Add to this cruelly delicate

organism the overpowering

necessity to create, create, create - - so that without the creating of

music or poetry or books or

buildings or something of meaning,

his very breath is cut off from him.

He must create, must pour out

creation. By some strange,

unknown, inward urgency he is not

really alive unless he is creating."

“I've always felt that a person's

intelligence is directly reflected

by the number of conflicting

points of view he can entertain

simultaneously on the same

topic.”

Abigail Adams

Pearl Buck

11

�VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

S

E

Q

12

U

O

I

A

C

MARCH 2012

L

U

B

1

2

Parenting a Sensitive and Intense Child

by Wendy Beeching

"Overachiever, mildly depressed, stressed, takes things too seriously." These things were told to

my oldest daughter all of her life by school officials and friends. I had to ask myself, "Is it true?" It

has been a journey to discover that she is highly sensitive and feels things intensely. It is who she is

and how she processes life. She needs to talk about things in order to verbally process what she is

experiencing. She is then able to move forward. Her perspective of the world was that it could be

very cruel and unjust. This led her to find a way to help others in need as she began to choose her

career.

We live in a rural area of Western Pennsylvania so teachers and administrators who recognized and

developed gifted children have been mostly non-existent. She was never the standardized test high

achiever but was a straight A student. When she qualified for the Davidson Institute Young

Scholars Program and the John Hopkins Talent Search we were amazed at what we learned about

gifted learners. We were also amazed at how much the public school system in our area was not

trained or even aware of this type of learner. The lists of myths that the advocating organizations

put together were the first clue as to what we were dealing with. Life was magnified in her eyes and

she needed someone to help her process all that she was experiencing. And, she needed support

from those who understood her. We got this from the Davidson Institute list of resources.

While she was growing up she had many of the same issues as other developing children who were

becoming independent. She could argue, slam doors, and rebel with the best of them. Through this

transitional period we learned that behavioral contracts were the best method for dealing with her.

All of the rules were decided upon with their consequences worked out ahead of time. This helped

de- escalate the emotions that ran so high in the house. It reduced reactivity to her behavior and

attitude. We were able to disengage from the negotiation cycles she would start. While there were

still many outbursts, we all survived this stage which lasted for about four or five years.

In high school, she qualified for an early college program where she earned high school credit

concurrently while attending her freshmen year. She was very shy and quiet in that environment but

performed well academically. She decided on a major, got involved in leadership roles with many

organizations on campus, traveled on care-breaks where she helped people in other states and

other countries. She really blossomed from being shy to taking the lead.

She then got accepted into physician assistant school where she has done very well. Her

personality suits the helping profession. She is now studying hard to do well on the competency

standardized tests required by the program. Being an intense person makes these high stakes

tests high anxiety situations so extra study skills have been employed.

When she works with the medical doctors during her medical rotations she realizes that her

sensitivity is a strength to embrace. She is able to relay medical education to her patients so that

they understand how to take better care of themselves. She has compassion for those patients

when they share their stories with her. She is then able to refer them to the right place for further

support to help them with their multiple needs.

12

�VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

S

E

Q

13

U

O

I

A

C

MARCH 2012

L

U

B

1

3

We have two younger children who are gifted as well. As a parent, I am now more confident in

advocating in the public schools. I regularly seek outside assessments so that our children learn

about themselves from more than one source. I have them tested so that standardized testing is

not such an enormous hurdle. My husband and I now try to approach discipline by drawing up

behavioral contracts immediately upon a hot topic where clarity in rules is necessary and allow our

children to make their own mistakes within reason. It is always a balance between stepping in and

watching from the sidelines as they discover who they are and how hard they need to apply

themselves. I can say that while our oldest daughter challenged us to try different parenting

techniques; she has helped raise our parenting skill level for her siblings. She also raised our

awareness of the importance of identifying and getting specific help for gifted education.

Words cannot express how rich this experience has been emotionally. It has taken much research

and full focus to strategize through each developmental phase all the way to her becoming

independent. We know that she will still need us from time to time but mostly just to listen as she

makes decisions for herself based on her own awareness.

Thank you to all of the groups who advocate for gifted learners. You are helping parents more

effectively raise their children. And you are helping children understand who they are as they

navigate through the measurements and standards that aren't always a match for the gifted student.

Both of these supports are powerful life changers for the gifted learner.

Now, our oldest daughter is getting ready to graduate and move on with her professional life. We

hear from her less and less as she is able to cope with her personal and professional life. We are

proud of her. At the same time, it is hard to let go because we were needed so intensely for many

years. I know she will always experience life intensely. But, now, she has the life skills to do it

without us.

Recommended Name Change

The Counseling and Guidance Network greatly appreciates the efforts of our school counselors

in meeting the affective needs of gifted children. The network, though, has expanded beyond a

focus on counseling and guidance. To better reflect the changes that have taken place and the

current reality of the network and its membership, a name change has been recommended. The

name “Social and Psychological Network” seemed most fitting to most of the network members.

This name more accurately describes the work carried out and the mission of our

multidimensional network. As past-chair of our network, Dr. Susan Jackson stated, “We wanted

to be sure to honor the history and roots of our network–counseling and guidance–while being

inclusive of essential stakeholders such as teachers, parents, researchers, educational and

clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, social workers and others—all of whom act on behalf of the

social and psychological needs of gifted children as represented in our CG sessions, our

academic work and in the field.”

13

�VOLUME 8, ISSUE 1

S

E

Q

14

U

O

I

A

C

MARCH 2012

L

U

B

1

4

Mission of the NAGC Counseling and Guidance Network

The Counseling & Guidance Network recognizes the critical need for attention to the affective

needs of the gifted individual. This Network is dedicated to addressing the social and emotional

growth of the gifted and talented. In addition, emphasis is placed on planning and implementing

a variety of systems and services for meeting these needs. If you are interested in joining you

must first be a member of NAGC. To get details on how to join, go to:

http://www.nagc.org/get-involved/join-nagc

NAGC Counseling and Guidance Network Officers

Jillian Gates, Doctoral Candidate

Chair

Bronwyn MacFarlane, PhD

Chair Elect

Angela Housand, PhD

Program Chair

Susan Jackson, MA, RCC

Past Chair

William Goff II, PhD and

Merzili Villanueva, PhD Student

Newsletter Editors

Call for Articles

The Counseling and Guidance Network of NAGC is seeking submissions for its May newsletter.

While accepting research, clinical, and scholarly position papers, we also welcome experiential

narratives from our parents or students that address our theme for the year: Meeting the nonintellective needs of gifted children who are highly sensitive, intense, and/or have characteristics

of overexcitabilities. If your child fits this description, please consider submitting a piece that

provides insights or ideas on how parents can support these children; how the experience of

raising one of these children effects the rest of the family; what you have found to be effective

parenting strategies; what you would like experts or researchers to do; and/or what you see as

the most serious concerns and most remarkable delights in parenting such a child. If you want to

submit an article or wish to learn more please send an email to nagc.cg.newsletter@gmail.com.

Article submissions must be received by April 27 and should be no longer than 2,000 words.

14

�

Merzili Villanueva

Merzili Villanueva